Abstract

Head lice (Pediculus humanus capitis) infestations are not a primary health hazard or a vector for disease, but they are a societal problem with substantial costs. Diagnosis of head lice infestation requires the detection of a living louse. Although pyrethrins and permethrin remain first-line treatments in Canada, isopropyl myristate/ST-cyclomethicone solution and dimeticone can be considered as second-line therapies when there is evidence of treatment failure.

Keywords: Dimeticone solution, Head lice, Infestations, Isopropyl myristate/cyclomethicone solution, Permethrin, Pyrethrin

Head lice (Pediculus humanus capitis) are a persistent and easily communicable cause of infestations, particularly in school-aged children (1,2). Unlike body lice, head lice are not a primary health hazard, a sign of poor hygiene or a vector for disease (3,4), but they are a common societal problem (2) and relatively expensive to treat. The annual cost of treating head lice in the United States is estimated to be at least US$500 million (5).

The present practice point updates a previous Canadian Paediatric Society document from 2008 (6) and highlights newer treatment products. It also reviews more recent information concerning treatment failures.

THE AGENT

Head lice are wingless, 2 mm to 4 mm long (as adults), six-legged, bloodsucking insects that live on the human scalp (7). Infested children usually carry less than 20 mature head lice (and often <10) at a time, which live 3 to 4 weeks if left untreated (3,8,9). Head lice live close to the scalp surface, which provides food, warmth, shelter and moisture (3,9). The head louse feeds every 3 to 6 hours by sucking blood, injecting saliva simultaneously. After mating, the adult female louse can produce five or six eggs (nits) per day for 30 days, each ‘glued’ to a hair shaft near the scalp (8,9). The eggs hatch 9 to 10 days later into nymphs that molt several times over the next 9 to 15 days to become adult head lice (6). The hatched empty eggshells remain on the hair but are not a source of reinfestation. Nymphs and adult head lice can survive for only 1 to 2 days away from the human host (10). While eggs can survive away from the host for up to 3 days, they require the higher temperatures found near the scalp to hatch (3).

THE INFESTATION

An infestation with lice is called pediculosis and usually involves less than 10 live lice (3). Itching occurs if the individual with lice becomes sensitized to antigenic components in the saliva injected as the louse feeds (2,3). On the first infestation, sensitization commonly takes 4 to 6 weeks (3,4). However, some individuals remain asymptomatic and never itch (3). In cases with heavy infestations, secondary bacterial infection of the excoriated scalp may occur.

TRANSMISSION

Head lice are spread mainly through direct head-to-head (hair-to-hair) contact (4,11). Lice do not hop or fly, but can crawl rapidly (23 cm/minute under natural conditions) (10). The role of fomites in transmission is controversial (10). Two studies from Australia suggest that in the home, pillowcases present only a small risk (11), while in the classroom, carpets pose no risk (12). Pets are not vectors for human head lice (13).

DIAGNOSIS

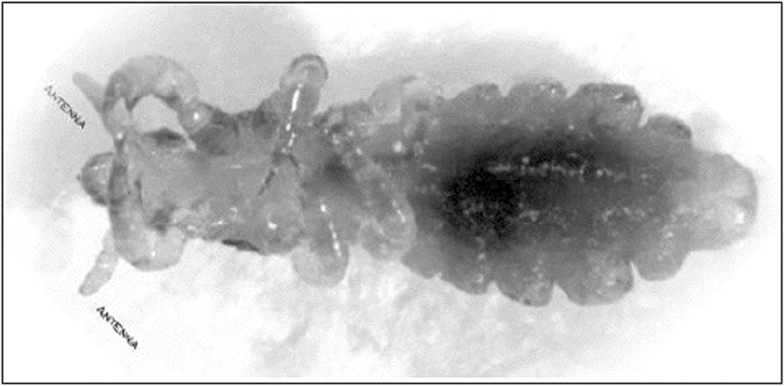

Definitive diagnosis of head lice infestation requires the detection of a living louse (Figure 1) (2,4,9). The presence of nits indicates a past infestation that may not be currently active.

Figure 1.

An adult louse measures 2 mm in length. Reproduced with permission from the National Pediculosis Association: http://www.headlice.org/faq/lousology.htm.

Because head lice move quickly, their detection requires a degree of expertise and experience. One Israeli study (14) involving experienced parasitologists found that using a fine-toothed lice comb was four times more effective and twice as fast as visually examining the scalp to detect live head lice and diagnose an infestation.

Another study (15) documented that health care providers and lay personnel frequently overdiagnose or misdiagnose pediculosis (15) and often fail to distinguish active from past infestations, particularly when relying on nit detection only. School nurses were adept at spotting nits but less able to distinguish active from past infestations. A viable nit is most likely to be found less than 0.6 cm away from the scalp (16). It is seen on microscopy as an intact, hydrated mass or developing embryo (15). Without microscopy, the ability to distinguish viable from nonviable nits is difficult, which is why diagnosing an infestation by nit detection alone is not reliable (15).

Finding nits close to the scalp is, at best, a modest predictor of possible active infestation. While one study from Georgia (16) found that having ≥5 nits within 0.6 cm of the scalp was a risk factor for infestation in children, <32% of such cases were actively infested (16). For children with less than five nits close to the scalp, only 7% became actively infested. Therefore, having nits close to the scalp does not necessarily indicate that a live infestation is underway or will occur.

TREATMENT

Well-established treatment options for a proven head lice infestation include topical insecticides and oral agents. Noninsecticidal products that have been approved by Health Canada since the last Canadian Paediatric Society statement was published in 2008 can all be obtained over the counter.

TOPICAL INSECTICIDES

Table 1 lists the topical insecticides (pyrethrins and permethrin 1%) currently available in Canada for treating head lice infestations, with their active ingredients, methods of use and other guidance. Two other products, malathion lotion (0.5%) and crotamiton lotion (10%), are not available in Canada.

Table 1.

Topical treatments for head lice infestations

| Trade name, approximate retail cost | Active ingredients | Method of use | Comments | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Insecticides | ||||

| Pyrethrins | ||||

| First-line treatment in Canada, although resistance is being documented elsewhere (8,35) | R&C shampoo + conditioner $11.99 for 50 mL, $33.99 for 200 mL | Pyrethrin, piperonyl butoxide Made from natural chrysanthemum extracts Neurotoxic to lice, but very low toxicity to humans | • Apply thoroughly to dry hair and scalp that does not have residuefrom a conditioner, gel, creamor other grooming product | • True allergic reactions are rare, but possible if allergy to ragweed is present• May cause an itchy or mild burning sensation on scalp*• An acceptable treatment for confirmed cases of head lice in children ≥2 months of age |

| • Soak with a minimum of 25 mL | ||||

| • Let sit 10 min | ||||

| • Add a small amount of water to form lather and work into hair | ||||

| • Rinse well with cool water, minimizing exposure elsewhereon the body | ||||

| • Repeat treatment 7–10 days later* | ||||

| Permethrin | ||||

| First-line treatment in Canada, although resistance is being documented elsewhere (5,19,35,36) | Kwellada-P creme rinse Nix creme rinse $13.99 for 59 mL, $16.79 for 118 mL | 1% permethrin (a synthetic pyrethroid) Neurotoxic to lice, but very low toxicity to humans | • After washing hair with conditioner-free shampoo, rinse, towel dry, and apply enough permethrin creme rinse to saturate hair and scalp | • Does not cause allergic reactions• May cause an itchy or mild burning sensation on scalp*• An acceptable treatment for confirmed cases of head lice in children ≥2 months of age |

| • Let sit for 10 min | ||||

| • Rinse well with cool water, minimizing body exposure | ||||

| • Towel dry | ||||

| • Repeat in 7 days* | ||||

| Noninsecticidal treatments | ||||

| Isopropyl myristate/ ST-cyclomethicone solution (34) | Resultz rinse $21.99 for 120 mL, $36.99 for 240 mL | 50% isopropyl myristate and 50% ST-cyclomethiconeDissolves the waxy exoskeletonof lice, leading to dehydration and death | • Use a towel to prevent contactwith eyes and to keep clothes dry | • May cause local irritation• Not recommended for use on infants or children <4 years of age• If contact with eyes occurs, flush well with water immediately |

| • Keep eyes closed throughout process, including the 10-min wait time | ||||

| • Thoroughly apply to dry hair and scalp | ||||

| • 30–60 mL for short hair, 60–90 mL for shoulder-length hair, 90–120 mL for long hair | ||||

| • Keep product on hair and scalp for 10 min | ||||

| • Rinse off with warm water | ||||

| • Repeat in 7 days | ||||

| Dimeticone solution | NYDA $36.99 for 50 mL | 92% concentration of silicone oil dimeticone flows into breathing system to suffocate lice, nymphs and egg embryos | • Spray all over hair, massage in well | • Do not use in children <2 years of age |

| • Leave on for at least 30 min, then comb well into hair | • Low risk of eye irritation, but if contact occurs, flush well with water immediately | |||

| • Leave on overnight, then wash with any shampoo | ||||

| • Repeat in 8–10 days | ||||

| • 10 mL for short hair, 18 mL for shoulder-length hair, 22 mL for long hair, 34 mL for very long hair | ||||

Toxicity

Both pyrethrins and permethrin have minimal percutaneous absorption and favourable safety profiles (9). To minimize exposure elsewhere on the body to a topical insecticide, do not sit a child in the bath to rinse hair. Instead, protect the skin with towels and rinse well, using cool water.

Lindane is no longer considered acceptable therapy for head lice because of the potential risks for neurotoxicity and bone marrow suppression following percutaneous absorption (8,17). The Food and Drug Administration in the USA has issued periodic advisories concerning the use of lindane- containing products for the treatment of lice and scabies. Neurological side effects have been reported in people who used lindane correctly, although the most serious outcomes, including death and hospitalizations, occurred after multiple applications or oral ingestion. A safe interval for the reapplication of lindane has not been established (17). The pharmaceutical use of lindane has also been banned in California since 2002 due to concerns about its presence in waste water. A follow-up study published in 2008 showed a marked reduction of lindane levels compared with levels before the California ban (18). The WHO has recently recategorized lindane as a probable carcinogen (19).

Resistance

An increasing resistance of head lice to pyrethrins, permethrin and lindane has been reported. In 2010, Marcoux et al. (20) found a resistant allele (R allele) frequency in 133 of 137 head lice populations tested for Canada, which could explain treatment failure rates. However, because these products are effective in more cases than these data imply, the precise relationship between R allele and treatment failure remains unclear. Rule out the following much more common possibilities before considering resistance (4,15):

• Misdiagnosis or over-diagnosis. A true diagnosis requires detecting live lice before treatment; and

• Reinfestation after a previous treatment.

If two permethrin applications 7 days apart do not eradicate live lice, consider administering a full treatment course using a medication from another class.

Note especially that topical insecticides may normally cause scalp rash, itching or a mild burning sensation (8). Be sure to remind families that itching after treatment with a topical insecticide is NOT a symptom of reinfestation. As with the initial diagnosis, diagnosing a reinfestation requires the detection of live lice. If post-treatment itching is bothersome, a topical steroid and/or an antihistamine may provide relief (4).

TOPICAL NONINSECTICIDAL PRODUCTS

Health Canada has approved the use of a new noninsecticidal product containing isopropyl myristate 50% and ST-cyclomethicone 50% (Resultz, Nycomed-Takeda Canada Inc.) for the treatment of head lice in children ≥4 years of age. This product works by dissolving the insect’s waxy exoskeleton, causing dehydration and death. The product is applied to a dry scalp and rinsed off in 10 minutes. Because this product is not ovicidal, a second application 1 week later is recommended. Several small phase II trials (200 to 300 participants only) have demonstrated efficacy and minimal side effects, the most common being mild erythema and pruritis of the scalp (21–24).

A noninsecticidal product containing 92% concentration of silicone oil dimeticone (NYDA) is also available in Canada (25,26). Silicone oil dimeticone affects the insect’s breathing apparatus and is effective against lice, nymphs and egg embryos. A second treatment is recommended after 8 to 10 days. This product is not recommended for use in children less than 2 years of age. To date, neither toxicity nor resistance are reported to be at issue.

Benzyl alcohol lotion 5% (Ulesfia lotion) is also approved for use in Canada. Benzyl alcohol is highly effective against live lice but is not ovicidal. A second treatment 9 days after the first treatment is required for a full treatment course. Benzyl alcohol lotion is approved for use in individuals 6 months to 60 years of age, and skin irritation is the only common side effect (27). This product is quite expensive compared with most other head lice treatments.

ORAL HEAD LICE THERAPIES

Data to support the use of oral agents in treating head lice are limited. Although trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole was used to treat head lice in one randomized trial (28), both alone and in combination with topical permethrin, concerns have since been raised about the diagnostic criteria used and this drug’s potential for promoting bacterial resistance and reducing its value in other settings if use against head lice becomes widespread (29). There are no published large trials for trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, and it is not approved for use in Canada against head lice.

There have been reports (30,31) regarding both the oral and topical use of ivermectin, an antihelminthic agent, to treat head lice. Treatment consists of two single oral doses of 200 µg/kg spaced 7 to 10 days apart. Ivermectin is potentially neurotoxic and should not be used in children who weigh less than 15 kg (4). This drug is available in Canada only through Health Canada’s Special Access Programme (31). While topical ivermectin 0.5% is now available in the United States, it is not yet approved in Canada. A study of concentrations from 0.15% to 0.5% found best results of being louse-free with 0.5% (32). A second study of 0.5% topical ivermectin found 94.9% of treated individuals to be louse-free after 2 days. Occasional cases of minor eye irritation and mild skin burning were the only reported side effects (33).

WET COMBING

There is little evidence to support wet combing as a primary treatment for head lice (21,34). In a randomized trial of 4037 school children in Wales, UK (21) the mechanical removal of lice by combing wet hair with a fine-toothed comb every 3 to 4 days for 2 weeks was compared with two applications of topical 0.5% malathion lotion, 7 days apart (21). Wet combing resulted in a cure (no detection of live lice after 2 weeks) in 38% of cases, while the malathion treatment cured 78% of cases (21). Another study combining wet combing with topical 1% permethrin treatment did not improve on results obtained with permethrin treatment alone when assessed at day 2, 8, 9 and 15 (combing 72.7%, no combing 78.3%) (21). While vinegar has been suggested as a home remedy to aid wet combing, there are no studies showing its benefit.

OTHER PRODUCTS

A number of household products, such as mayonnaise, petroleum jelly, olive oil, tub margarine and thick hair gel, have been suggested as treatments for head lice. Applying a thick coating of such agents to the hair and scalp and leaving it on overnight theoretically occludes lice spiracles and decreases respiration (8). However, these products are not very effective at killing of lice compared with topical insecticides (3). There are no published trials on the safety or efficacy of such home remedies.

While natural products (e.g., tea tree oil) and aromatherapy have been used to treat head lice, efficacy and toxicity data are not available to support either therapy (3,9). One small study in Israel (34) found that a product containing coconut, anise and ylang ylang oils, applied to hair three times at 5-day intervals, was as successful as the control pediculicide.

Using flammable, toxic and dangerous substances like gasoline or kerosene to treat head lice or using products intended for treating lice in animals are not recommended under any circumstances.

SCHOOL AND CHILD CARE HEAD LICE AND NIT POLICIES

There is no sound medical rationale for excluding a child with nits or live lice from school or child care. A full course of treatment and avoiding close head-to-head activities are recommended. The American Academy of Pediatrics and the Public Health Medicine Environmental Group in the UK also discourage ‘no nit’ school policies (2,4,10).

The families of children in the same classroom or child care group where a case of active head lice has been detected should be alerted. Information on diagnosis and management of head lice from a credible source should be shared, along with clear messages that head lice are neither a disease risk nor a sign of lack of cleanliness.

THE ROLE OF ENVIRONMENTAL DECONTAMINATION

Data on whether disinfecting personal, school or household items decreases the likelihood of reinfestation are lacking (11,12). Because lice live close to the scalp, nits are unlikely to hatch at room temperature (3,10) and environmental cleaning is not warranted. At most, washing items in close or prolonged contact with the head (e.g., hats, pillowcases, brushes and combs) may be warranted. Wash such items in hot water (≥66°C) and dry them in a hot dryer for 15 minutes. Storing any item in a sealed plastic bag for 2 weeks will kill both live lice and nits (3,11).

THE ROLE OF HEALTH CARE PROVIDERS

Given the prevalence of head lice infestations and the anxiety they cause—for children, parents and child care or school staff—health care providers are uniquely qualified to dispel myths and provide accurate information on diagnosis, misdiagnosis and management strategies (2). Be sure to reinforce with parents and local school authorities that while head lice infestations are common, they do not indicate uncleanliness or spread disease.

RECOMMENDATIONS

Clinicians should provide parents with the most up-to-date information on head lice, helping to dispel long-held myths. Key messages include:

• Head lice infestations are common in school children but are not associated with disease spread or poor hygiene.

• Head lice infestations can be asymptomatic for weeks.

• Misdiagnosis of head lice infestations is common. Diagnosis requires detection of live head lice. Detecting nits alone does not indicate active infestation.

• Environmental cleaning or disinfection following the detection of a head lice case is not warranted. Head lice or nits do not survive for long away from the scalp.

Clinicians should provide the following advice about treatment of head lice:

• Treatment with an approved, properly applied, topical head lice insecticide (two applications 7 to 10 days apart) is recommended when a case of active infestation is detected.

• When there is evidence of treatment failure—detection of live lice—using a full course of topical treatment from a different class of medication is recommended.

• The scalp may be itchy after applying a topical insecticide but itching does not indicate treatment resistance or a reinfestation.

• Topical insecticides can be toxic. Take care to avoid unnecessary exposure and, when indicated, minimize skin contact beyond the scalp.

• Excluding children with nits or live lice from school or child care has no rational medical basis and is not recommended.

• For children ≥2 months of age, permethrin and pyethrins are acceptable treatments for confirmed cases of head lice. Dimethicone can be used in children ≥2 years of age. Myristate/ST-cyclomethicone can be used in children ≥4 years of age. Benzoyl alcohol lotion is comparatively expensive but can be used in children ≥6 months of age.

Schools and child care facilities should consider that:

• Excluding children with nits or live lice from school or child care has no rational medical basis and is not recommended.

Acknowledgements

This practice point has been reviewed by the Infectious Diseases and Immunization Committee and the Drug Therapy and Hazardous Substances Committee of the Canadian Paediatric Society.

CPS COMMUNITY PAEDIATRICS COMMITTEE

Members: Carl Cummings MD (Chair), Umberto Cellupica MD (past Board Representative), Tara Chobotok MD, Sarah Gander MD, Alisa Lipson MD, Marianne McKenna MD (Board Representative), Julia Orkin MD, Larry Pancer MD, Anne Rowan-Legg MD (past member)

Liaison: Krista Baerg MD, CPS Community Paediatrics Section

Principal authors: Carl Cummings MD, Jane C Finlay MD, Noni E MacDonald MD

References

- 1. Gratz NG. Human Lice: Their Prevalence, Control and Resistance to Insecticides: A Review 1985–1997. Geneva: World Health Organization, 1997. <whqlib-doc.who.int/hq/1997/WHO_CTD_WHOPES_97.8.pdf>(Accessed May 16, 2016). [Google Scholar]

- 2. Public Health Medicine Environmental Group. Head Lice: Evidence-based Guidelines Based on the Stafford Report 2012 Update <www.phmeg.org.uk/files/1013/2920/7269/Stafford_Headlice_Doc_revise_2012_version.pdf> (Accessed May 16, 2016).

- 3. Meinking TL. Infestations. Curr Probl Dermatol 1999;11(3):73 –118. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Frankowski BL, Weiner LB; Committee on School Health, Committee on Infectious Diseases. American Academy of Pediatrics Head lice. Pediatrics 2002;110(3):638–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Gur I, Schneeweiss R. Head lice treatments and school policies in the US in an era of emerging resistance: A cost-effectiveness analysis. Pharmacoeconomics 2009;27(9):725–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Finlay JC, MacDonald NE; Canadian Paediatric Society, Infectious Diseases and Immunization Committee. Head lice infestations: A clinical update. Paediatr Child Health 2008;13(8):692–704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Roberts RJ. Clinical practice. Head lice. N Engl J Med 2002;346(21):1645–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Jones KN, English JC 3rd. Review of common therapeutic options in the United States for the treatment of pediculosis capitis. Clin Infect Dis 2003;36(11):1355–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Nash B. Treating head lice. BMJ2003;326(7401):1256–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Burkhart CN. Fomite transmission with head lice: A continuing controversy. Lancet 2003;361(9352):99–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Speare R, Cahill C, Thomas G. Head lice on pillows, and strategies to make a small risk even less. Int J Dermatol 2003;42(8):626–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Speare R, Thomas G, Cahill C. Head lice are not found on floors in primary school classrooms. Aust N Z J Public Health 2002;26(3):208–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Harris J, Crawshaw JG, Millership S. Incidence and prevalence of head lice in a district health authority area. Commun Dis Public Health 2003;6(3):246–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Mumcuoglu KY, Friger M, Ioffe-Uspensky I, Ben-Ishai F, Miller J. Louse comb versus direct visual examination for the diagnosis of head louse infestations. Pediatr Dermatol 2001;18(1):9–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Pollack RJ, Kiszewski AE, Spielman A. Overdiagnosis and consequent mismanagement of head louse infestations in North America. Pediatr Infect Dis J 2000;19(8):689–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Williams LK, Reichert A, MacKenzie WR, Hightower AW, Blake PA. Lice, nits, and school policy. Pediatrics 2001;107(5):1011–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Centre for Drug Evaluation and Research. FDA Public Health Advisory: Safety of Topical Lindane Products for the Treatment of Scabies and Lice <www.fda.gov/Drugs/DrugSafety/PostmarketDrugSafetyInformationforPatientsandProviders/ucm110845.htm> (Accessed May 16, 2016).

- 18. Humphreys EH, Janssen S, Heil A, Hiatt P, Solomon G, Miller MD. Outcomes of the California ban on pharmaceutical lindane: Clinical and ecologic impacts. Environ Health Perspect 2008;116(3):297–302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. WHO, International Agency for Research on Cancer, 23 June 2015. IARC Monographs Evaluate DDT, lindane, and 2,4-D. Press Release no. 236 <www.iarc.fr/en/media-centre/pr/2015/pdfs/pr236_E.pdf> (Accessed June 9, 2016). [PubMed]

- 20. Marcoux D, Palma KG, Kaul N et al. . Pyrethroid pediculicide resistance of head lice in Canada evaluated by serial invasive signal amplification reaction. J Cutan Med Surg 2010;14(3):115–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Meinking TL, Clineschmidt CM, Chen C et al. . An observer-blinded study of 1% permethrin creme rinse with and without adjunctive combing in patients with head lice. J Pediatr 2002;141(5):665–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Burgess IF, Brown CM, Lee PN. Treatment of head louse infestation with 4% dimeticone lotion: Randomised controlled equivalence trial. BMJ 2005;330(7505):1423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Kaul N, Palma KG, Silagy SS, Goodman JJ, Toole J. North American efficacy and safety of a novel pediculicide rinse, isopropyl myristate 50% (Resultz). J Cutan Med Surg 2007;11(5):161–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Burgess IF, Lee PN, Brown CM. Randomised, controlled, parallel group clinical trials to evaluate the efficacy of isopropyl myristate/cyclomethicone solution against head lice. Pharm J 2008;280:371–5. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Heukelbach J, Pilger D, Oliveira FA, Khakban A, Ariza L, Feldmeier H. A highly efficacious pediculicide based on dimeticone: Randomized observer blinded comparative trial. BMC Infect Dis 2008;8:115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Burgess IF, Lee PN, Matlock G. Randomised, controlled, assessor blind trial comparing 4% dimeticone lotion with 0.5% malathion liquid for head louse infestation. PLOS One 2007;2(11):e1127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Meinking TL, Villar ME, Vicaria M et al. . The clinical trials supporting benzyl alcohol lotion 5% (Ulesfia): A safe and effective topical treatment for head lice (Pediculosis humanus capitis). Pediatr Dermatol 2010;27(1):19–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Hipolito RB, Mallorca FG, Zuniga-Macaraig ZO, Apolinario PC, Wheeler-Sherman J. Head lice infestation: Single drug versus combination therapy with one percent permethrin and trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole. Pediatrics 2001;107(3):E30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Pollack RJ. Head lice infestation: Single drug versus combination therapy. Pediatrics 2001;108(6):1393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Meinking TL, Mertz-Rivera K, Villar ME, Bell M. Assessment of the safety and efficacy of three concentrations of topical ivermectin lotion as a treatment for head lice infestation. Int J Dermatol 2013;52(1):106–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Health Canada. Drugs and Health Products <www.hc-sc.gc.ca/dhp-mps/acces/drugs-drogues/index-eng.php> (Accessed May 16, 2016).

- 32. Pariser DM, Meinking TL, Bell M, Ryan WG. Topical 0.5% ivermectin lotion for treatment of head lice. N Engl J Med 2012;367(18):1687–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Roberts RJ, Casey D, Morgan DA, Petrovic M. Comparison of wet combing with malathion for treatment of head lice in the UK: A pragmatic randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2000;356(9229):540–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Mumcuoglu KY, Miller J, Zamir C, Zentner G, Helbin V, Ingber A. The in vivo pediculicidal efficacy of a natural remedy. Isr Med Assoc J 2002;4(10):790–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Yoon KS, Previte DJ, Hodgdon HE et al. . Knockdown resistance allele frequencies in North American head louse (Anoplura: Pediculidae) populations. J Med Entomol 2014;51(2):450–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Pollack RJ, Kiszewski A, Armstrong P et al. . Differential permethrin susceptibility of head lice sampled in the United States and Borneo. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 1999;153(9):969–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]