Key Points

Question

What are the patient, clinician, and hospital characteristics associated with use of cardiac resynchronization therapy defibrillators (CRT-Ds) and what is the extent of hospital variation in CRT-D use?

Findings

In this analysis from the National Cardiovascular Data Registry Implantable Cardioverter Defibrillator Registry, most eligible patients received CRT-D. However, black race and public insurance were associated with lower CRT-D use and, after accounting for these and other factors, significant hospital-level variation in CRT-D use remained.

Meaning

Strategies to optimize the use of CRT-D among patients with the strongest guideline indications for clinical benefit are needed.

Abstract

Importance

Cardiac resynchronization therapy (CRT) reduces the risk for mortality and heart failure–related events in select patients. Little is known about the use of CRT in combination with an implantable cardioverter defibrillator (ICD) in patients who are eligible for this therapy in clinical practice.

Objective

To (1) identify patient, clinician, and hospital characteristics associated with CRT defibrillator (CRT-D) use and (2) determine the extent of hospital-level variation in the use of CRT-D among guideline-eligible patients undergoing ICD placement.

Design, Setting, and Participants

Multicenter retrospective cohort from 1428 hospitals participating in the National Cardiovascular Data Registry ICD Registry between April 1, 2010, and June 30, 2014. Adult patients meeting class I or IIa guideline recommendations for CRT at the time of device implantation were included in this study.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Implantation of an ICD with or without CRT.

Results

A total of 63 506 eligible patients (88.6%) received CRT-D at the time of device implantation. The mean (SD) ages of those in the ICD and CRT-D groups were 67.9 (12.2) years and 68.4 (11.5) years, respectively. In hierarchical multivariable models, black race was independently associated with lower use of CRT-D (odds ratio [OR], 0.77; 95% CI, 0.71-0.83) as was nonprivate insurance (OR, 0.90; 95% CI, 0.85-0.95 for Medicare and OR, 0.73; 95% CI, 0.65-0.82 for Medicaid). Clinician factors associated with greater CRT-D use included clinician implantation volume (OR, 1.01 per 10 additional devices implanted; 95% CI, 1.01-1.01) and electrophysiology training (OR, 3.13 as compared with surgery-boarded clinicians; 95% CI, 2.50-3.85). At the hospital level, the overall median risk-standardized rate of CRT-D use was 79.9% (range, 26.7%-100%; median OR, 2.08; 95% CI, 1.99-2.18).

Conclusions and Relevance

In a national cohort of patients eligible for CRT-D at the time of device implantation, nearly 90% received a CRT-D device. However, use of CRT-D differed by race and implanting operator characteristics. After accounting for these factors, the use of CRT-D continued to vary widely by hospital. Addressing disparities and variation in CRT-D use among guideline-eligible patients may improve patient outcomes.

This cohort study identifies patient, clinician, and hospital characteristics associated with cardiac resynchronization therapy defibrillator use and determine the extent of hospital-level variation in this use among guideline-eligible patients undergoing implantable cardioverter defibrillator placement.

Introduction

The addition of cardiac resynchronization therapy (CRT) to an implantable cardioverter defibrillator (ICD) reduces the risk for mortality and heart failure events in select patients. Therefore, it is important to ensure patients who have a guideline recommendation for CRT are considered for this therapy at the time of ICD implantation. To our knowledge, few data are available on the contemporary use of CRT among guideline-eligible patients undergoing ICD implantation and the factors associated with use of this therapy.

We analyzed data from the National Cardiovascular Data Registry (NCDR) ICD Registry to describe overall use of CRT among eligible patients undergoing ICD implantation; identify the patient, clinician, and hospital characteristics associated with CRT defibrillator (CRT-D) use; and determine the extent of hospital-level variation in CRT-D use.

Methods

Study Population and Eligibility

We identified 71 662 adult patients at 1428 NCDR ICD Registry–participating hospitals who met class I or IIa guideline recommendations and underwent primary prevention ICD or CRT-D implantation between April 1, 2010, and June 30, 2014. To reflect changes in guideline recommendations for CRT during the study, we used a time-dependent definition for CRT eligibility (eTable in the Supplement). Patients who underwent device implantation prior to publication of the 2012 Focused Update to the guidelines were included if they met criteria for class I or IIa indication for CRT based on the 2008 guidelines. Patients implanted with a device after publication of the 2012 Focused Update were included if they met criteria for a class I or IIa indication for CRT based on the 2012 Focused Update.

Institutional review board approval for this study was waived because data were from a national quality registry.

Implanted Device Type Outcome

The primary outcome was the implantation of an ICD alone or CRT-D device.

Candidate Predictor Variables for Use of CRT-D

We evaluated patient (demographics, insurance type [Medicare and Medicaid were considered as public insurance], comorbid conditions, and QRS morphology), clinician (type of training and ICD implantation volume), and hospital (bed number, teaching status, and cardiac procedural capability) variables associated with CRT-D implantation. The rate of missing data was less than 1% for all variables.

Statistical Analysis

We compared patient, implanting operator, and hospital characteristics by receipt of ICD alone or CRT-D using χ2 tests for categorical variables and t tests for continuous variables. We then determined the independent association between candidate predictor variables at the patient, implanting operator, and hospital levels with CRT-D use from a hierarchical, hospital-specific random-effect model to account for clustering of patients within hospitals.

At the hospital-level, we determined the proportion of patients receiving CRT-D. Using the method currently endorsed by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services for hospital profiling, we used hierarchical regression to assess hospital-level variation in risk-standardized CRT-D use. First, we calculated the ratio of predicted CRT-D use to expected CRT-D use for each hospital, where predicted CRT-D use was computed as the sum of the predicted probabilities of CRT-D use including that hospital’s specific random effect, and expected CRT-D use was computed as the sum of the predicted probabilities excluding the hospital effect, that is, for an “average” other hospital within the cohort. Next, we multiplied each hospital’s predicted to expected ratio by the overall study CRT-D use rate and scaled the resulting estimates to fit a range that did not exceed 100% for hospital-level risk-standardized CRT-D use rates.

Results

Of the 71 662 patients eligible for CRT at the time of device implantation, 63 506 (88.6%) received a CRT-D device, with 39 860 (62.8%) meeting a class I indication for CRT and 23 646 (37.2%) meeting a class IIa indication.

Patient, clinician, and hospital characteristics by use of CRT-D vs ICD alone are shown in Table 1. The association between patient, implanting operator, and hospital characteristics with CRT-D implantation as determined from our hierarchical regression analysis are summarized in Table 2. Patient factors independently associated with a higher likelihood of CRT-D implantation included increasing age and increasing New York Heart Association class, while patient factors associated with a lower likelihood of CRT-D implantation included black race, nonprivate insurance (including Medicare and Medicaid), atrial fibrillation/flutter, non–left bundle branch block QRS morphology, ischemic heart disease, cerebrovascular disease, diabetes, and current hemodialysis. Clinician factors independently associated with higher rates of CRT-D use included higher device implanting volume and electrophysiology-trained implanting operator. Hospitals without coronary artery bypass graft capability were less likely to implant CRT-D.

Table 1. Patient, Clinician, and Hospital Characteristics for Patients Receiving ICD vs CRT-D Among All Patients Eligible for CRT.

| Characteristic | No. (%) | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| ICD (n = 8156) |

CRT-D (n = 63 506) |

||

| Patient Characteristics | |||

| Demographics | |||

| Age, mean (SD), y | 67.9 (12.2) | 68.4 (11.5) | <.01 |

| Male | 5744 (70.4) | 40 992 (64.5) | <.01 |

| Race | |||

| White | 6678 (81.9) | 53 887 (84.9) | <.01 |

| Black/African American | 1210 (14.8) | 8005 (12.6) | |

| Other | 268 (3.3) | 1614 (2.5) | |

| Insurance | |||

| Private | 4548 (55.8) | 39 430 (62.1) | <.01 |

| Medicare | 2731 (33.5) | 18 900 (29.8) | |

| Medicaid | 475 (5.8) | 2726 (4.3) | |

| Other | 402 (4.9) | 2450 (3.9) | |

| Clinical Characteristics | |||

| Atrial fibrillation/flutter | 2520 (30.9) | 17 685 (27.8) | <.01 |

| NYHA | |||

| II | 1239 (15.2) | 5387 (8.5) | <.01 |

| III | 6488 (79.5) | 54 923 (86.5) | |

| IV | 429 (5.3) | 3196 (5.0) | |

| Ischemic heart disease | 5101 (62.5) | 33 370 (52.5) | <.01 |

| Abnormal intraventricular conduction | |||

| LBBB | 4458 (54.7) | 51 391 (80.9) | <.01 |

| RBBB | 2172 (26.6) | 6983 (11.0) | |

| Nonspecific delay | 1306 (16.0) | 4449 (7.0) | |

| Other | 220 (2.7) | 683 (1.1) | |

| Weight, mean (SD), kg | 87.3 (24.3) | 86.8 (22.8) | .09 |

| Cerebrovascular disease | 1359 (16.7) | 9117 (14.4) | <.01 |

| Chronic lung disease | 2082 (25.5) | 15 048 (23.7) | <.01 |

| Diabetes | 3720 (45.6) | 26 466 (41.7) | <.01 |

| Current dialysis | 363 (4.5) | 1433 (2.3) | <.01 |

| Hypertension | 6783 (83.2) | 52 034 (81.9) | <.01 |

| Operator characteristics | |||

| EP operator ICD training | |||

| Board-certified EP/EP fellowship | 5751 (70.5) | 53 374 (84.0) | <.01 |

| Surgery board | 199 (2.4) | 545 (0.9) | |

| Clinician ICD volume, mean (SD) | 224.3 (338.7) | 277.6 (314.1) | <.01 |

| Hospital Characteristics | |||

| Beds | |||

| ≤200 | 1151 (14.1) | 7549 (11.9) | <.01 |

| >200-400 | 3072 (37.7) | 23 157 (36.5) | |

| >400 | 3833 (47.0) | 32 113 (50.6) | |

| Teaching hospital | 4391 (53.8) | 36 812 (58.0) | <.01 |

| Cardiac facility | |||

| CABG | 6861 (84.1) | 55 474 (87.4) | <.01 |

| Cath | 396 (4.9) | 1733 (2.7) | |

| Other | 799 (9.8) | 5612 (8.8) | |

Abbreviations: CABG, coronary artery bypass graft; Cath, cardiac catheterization; CRT-D, combination implantable cardioverter defibrillator and cardiac resynchronization therapy; EP, electrophysiology; ICD, implantable cardioverter defibrillator; LBBB, left bundle branch block; NYHA, New York Heart Association; RBBB, right bundle branch block.

Table 2. Patient, Operator, and Hospital Characteristics Associated With CRT-D Use Among all Eligible Patients.

| Characteristics | OR (95% CI) | P Value |

|---|---|---|

| Patient Characteristics | ||

| Demographics | ||

| Age, 10 y | 1.04 (1.01-1.06) | <.01 |

| Female | 0.98 (0.93-1.04) | .57 |

| Race | ||

| White | 1 [Reference] | <.01 |

| Black/African American | 0.77 (0.71-0.83) | |

| Other | 0.89 (0.77-1.04) | |

| Insurance | ||

| Private | 1 [Reference] | <.01 |

| Medicare | 0.90 (0.85-0.95) | |

| Medicaid | 0.73 (0.65-0.82) | |

| Other | 0.76 (0.67-0.86) | |

| Clinical Characteristics | ||

| Atrial fibrillation/flutter | 0.88 (0.84-0.94) | <.01 |

| NYHA | ||

| II | 1 [Reference] | <.01 |

| III | 3.62 (3.33-3.94) | |

| IV | 4.12 (3.59-4.73) | |

| Ischemic heart disease | 0.76 (0.72-0.80) | <.01 |

| Abnormal intraventricular conduction | ||

| LBBB | 1 [Reference] | <.01 |

| RBBB | 0.23 (0.22-0.25) | |

| Nonspecific delay | 0.24 (0.23-0.26) | |

| Other | 0.22 (0.19-0.27) | |

| Weight, per 1 kg | 1.00 (1.00-1.00) | .19 |

| Cerebrovascular disease | 0.92 (0.86-0.98) | .01 |

| Chronic lung disease | 0.98 (0.92-1.04) | .45 |

| Diabetes | 0.94 (0.90-0.99) | .03 |

| Current dialysis | 0.58 (0.50-0.66) | <.01 |

| Hypertension | 1.04 (0.97-1.12) | .26 |

| Operator Characteristics | ||

| EP operator ICD training | ||

| Board-certified EP/EP fellowship | 1 [Reference] | <.01 |

| Surgery board | 0.32 (0.26-0.40) | |

| Operator ICD volume, 10 cases | 1.01 (1.01-1.01) | <.01 |

| Hospital Characteristics | ||

| Beds | ||

| ≤200 | 1 [Reference] | .64 |

| >200-400 | 1.06 (0.91-1.22) | |

| >400 | 1.08 (0.92-1.28) | |

| Teaching hospital | 0.97 (0.86-1.10) | .66 |

| Cardiac facility | ||

| CABG | 1 [Reference] | <.01 |

| Cath | 0.59 (0.48-0.73) | |

| Other | 0.73 (0.62-0.87) | |

Abbreviations: CABG, coronary artery bypass graft; Cath, cardiac catheterization; CRT-D, combination implantable cardioverter defibrillator and cardiac resynchronization therapy; EP, electrophysiology; ICD, implantable cardioverter defibrillator; OR, odds ratio; LBBB, left bundle branch block; NYHA, New York Heart Association; RBBB, right bundle branch block.

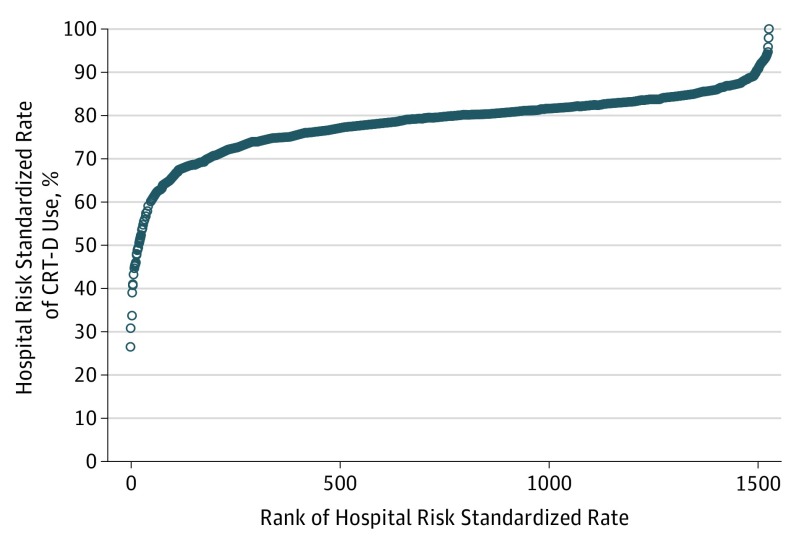

At the hospital level, the unadjusted median rate of CRT-D use was 89.2% (range, 0%-100%). After risk standardization that accounted for patient, implanting operator, and hospital characteristics, the median hospital risk-standardized rate of CRT-D use was 79.9% (range, 26.7%-100%; median odds ratio, 2.08; 95% CI, 1.99-2.18; Figure).

Figure. Hospital Variation in the Use of Cardiac Resynchronization Therapy Defibrillators (CRT-Ds) Among All Eligible Patients.

Variation in the risk-standardized rate of CRT-D use at the hospital level after adjustment that accounted for patient, implanting operator, and hospital characteristics is shown.

Discussion

In a national sample of CRT-eligible patients undergoing ICD implantation, we observed a high overall rate of CRT-D use. However, CRT-D was used inconsistently, suggesting opportunities exist to reduce variation in the use of this guideline-directed therapy.

Similar to prior studies demonstrating significantly lower use of ICD and CRT in black patients, we found black race was independently associated with a lower likelihood of CRT-D implantation. Previous work demonstrated a lower rate of use of ICD and CRT devices in those without insurance. Our findings suggest insurance type, and not simply the presence or absence of insurance coverage, is significantly related to the rate of CRT-D use.

To our knowledge, the relationship between operator characteristics and CRT-D use have not been described previously. We found electrophysiology-trained implanting operators were more likely to implant CRT-D among eligible patients. The underlying reasons for this association are not known, and we cannot exclude a contribution of referral patterns to nonelectrophysiology-trained clinicians for patients who elect to undergo ICD implantation alone. Further research to understand the nature of differences in CRT-D use by clinician training may provide insights on strategies to further optimize CRT-D use.

While implantation of CRT-D devices has increased over time in the United States, limited data exist regarding the presence and extent of hospital-level variation of CRT-D use. A prior analysis from the Get With The Guidelines–Heart Failure program included data from patients hospitalized with heart failure, of whom a minority (4.8%) had a new CRT device implanted prior to discharge, and found rates of new CRT placement prior to discharge varied by hospital. Our study from a large, national registry of patients undergoing device implantation demonstrated higher rates of CRT-D use than this prior analysis. One factor contributing to high rates of CRT-D use in our study may be our cohort included only patients receiving an ICD or CRT-D. Despite high rates of overall use, we observed broad hospital-level variation in the rate of CRT-D use, ranging from 26.7% to 100%. Although CRT-D implantation is associated with additional risk relative to ICD alone, the magnitude of risk is small relative to the risk associated with any device implantation. Therefore, variation in CRT-D use may be less likely to reflect variation in patient preference and more likely to reflect a treatment gap amenable to quality improvement.

Limitations

Several limitations to the current study should be acknowledged. First, the NCDR ICD Registry does not contain data on patients who were eligible for either ICD or CRT-D implantation but did not receive any device. Second, we could not account for unmeasured variables (including the rate of optimal medical therapy or patient preference) that may have influenced device choice. Third, our study may be subject to residual confounding. For example, the association between black race and CRT-D implantation may be influenced by socioeconomic status, which can also affect treatment decisions regarding cardiology devices. Fourth, we were unable to account for cases in which clinical judgment regarding CRT use may have appropriately conflicted with guideline recommendations.

Conclusions

Among patients with a guideline recommendation for CRT at the time of ICD implantation, we found black patients and those with nonprivate insurance were less likely to receive CRT-D, while patients treated by higher-volume operators and electrophysiology-trained clinicians were more likely to receive CRT-D. We observed wide hospital-level variation in CRT-D use in guideline-eligible patients. Future work should address strategies to reduce disparities in the use of CRT-D and improve rates of CRT-D use at sites with low rates of CRT-D implantation in eligible patients.

eTable. Patient Criteria Based on Strength of Guideline Recommendation for CRT.

References

- 1.Moss AJ, Hall WJ, Cannom DS, et al. ; MADIT-CRT Trial Investigators . Cardiac-resynchronization therapy for the prevention of heart-failure events. N Engl J Med. 2009;361(14):1329-1338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tang ASL, Wells GA, Talajic M, et al. ; Resynchronization-Defibrillation for Ambulatory Heart Failure Trial Investigators . Cardiac-resynchronization therapy for mild-to-moderate heart failure. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(25):2385-2395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tracy CM, Epstein AE, Darbar D, et al. ; American College of Cardiology Foundation; American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines; Heart Rhythm Society . 2012 ACCF/AHA/HRS focused update of the 2008 guidelines for device-based therapy of cardiac rhythm abnormalities: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines and the Heart Rhythm Society [published correction appears in Circulation. 2013;127(3):e357-359]. Circulation. 2012;126(14):1784-1800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Epstein AE, DiMarco JP, Ellenbogen KA, et al. ; American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines (Writing Committee to Revise the ACC/AHA/NASPE 2002 Guideline Update for Implantation of Cardiac Pacemakers and Antiarrhythmia Devices); American Association for Thoracic Surgery; Society of Thoracic Surgeons . ACC/AHA/HRS 2008 Guidelines for Device-Based Therapy of Cardiac Rhythm Abnormalities: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines (Writing Committee to Revise the ACC/AHA/NASPE 2002 Guideline Update for Implantation of Cardiac Pacemakers and Antiarrhythmia Devices): developed in collaboration with the American Association for Thoracic Surgery and Society of Thoracic Surgeons. Circulation. 2008;117(21):e350-e408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shah B, Hernandez AF, Liang L, et al. ; Get With the Guidelines Steering Committee . Hospital variation and characteristics of implantable cardioverter-defibrillator use in patients with heart failure: data from the GWTG-HF (Get With the Guidelines–Heart Failure) registry. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;53(5):416-422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Matlock DD, Peterson PN, Wang Y, et al. Variation in use of dual-chamber implantable cardioverter-defibrillators: results from the National Cardiovascular Data Registry. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172(8):634-641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mehra MR, Yancy CW, Albert NM, et al. Evidence of clinical practice heterogeneity in the use of implantable cardioverter-defibrillators in heart failure and post-myocardial infarction left ventricular dysfunction: findings from IMPROVE HF. Heart Rhythm. 2009;6(12):1727-1734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Peterson PN, Greiner MA, Qualls LG, et al. QRS duration, bundle-branch block morphology, and outcomes among older patients with heart failure receiving cardiac resynchronization therapy. JAMA. 2013;310(6):617-626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Borne RT, Peterson PN, Greenlee R, et al. Temporal trends in patient characteristics and outcomes among Medicare beneficiaries undergoing primary prevention implantable cardioverter-defibrillator placement in the United States, 2006-2010: results from the National Cardiovascular Data Registry’s Implantable Cardioverter-Defibrillator Registry. Circulation. 2014;130(10):845-853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Piccini JP, Hernandez AF, Dai D, et al. ; Get With the Guidelines Steering Committee and Hospitals . Use of cardiac resynchronization therapy in patients hospitalized with heart failure. Circulation. 2008;118(9):926-933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Masoudi FA, Mi X, Curtis LH, et al. Comparative effectiveness of cardiac resynchronization therapy with an implantable cardioverter-defibrillator versus defibrillator therapy alone: a cohort study. Ann Intern Med. 2014;160(9):603-611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.van Rees JB, de Bie MK, Thijssen J, Borleffs CJ, Schalij MJ, van Erven L. Implantation-related complications of implantable cardioverter-defibrillators and cardiac resynchronization therapy devices: a systematic review of randomized clinical trials. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;58(10):995-1000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Philbin EF, McCullough PA, DiSalvo TG, Dec GW, Jenkins PL, Weaver WD. Socioeconomic status is an important determinant of the use of invasive procedures after acute myocardial infarction in New York State. Circulation. 2000;102(19)(suppl 3):III107-III115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eTable. Patient Criteria Based on Strength of Guideline Recommendation for CRT.