This case series examines a series of patients diagnosed with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy and severe basal left ventricular outflow tract obstruction undergoing myectomy in whom the diagnosis of Anderson-Fabry cardiomyopathy was suspected by the cardiac surgeon intraoperatively and confirmed by histological and genetic examinations.

Key Points

Question

Is basal left ventricular outflow tract obstruction an exclusion criterion for Anderson-Fabry cardiomyopathy?

Findings

In this case series of 3 patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, we found that Anderson-Fabry cardiomyopathy may mimic hypertrophic cardiomyopathy and present with severely symptomatic left ventricular outflow tract obstruction. The diagnosis was suspected by the cardiac surgeon and confirmed by histological and genetic examinations.

Meaning

Screening for Anderson-Fabry cardiomyopathy should be performed even in the absence of red flags in patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy older than 25 years.

Abstract

Importance

Diagnostic screening for Anderson-Fabry cardiomyopathy (AFC) is performed in the presence of specific clinical red flags in patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM) older than 25 years. However, left ventricular outflow tract obstruction (LVOTO) has been traditionally considered an exclusion criteria for AFC.

Objective

To examine a series of patients diagnosed with HCM and severe basal LVOTO undergoing myectomy in whom the diagnosis of AFC was suspected by the cardiac surgeon intraoperatively and confirmed by histological and genetic examinations.

Design, Setting, and Participants

This retrospective analysis of patients undergoing surgical septal reduction strategies was conducted in 3 European tertiary referral centers for HCM from July 2013 to December 2016. Patients with a clinical diagnosis of obstructive HCM referred for surgical management of LVOTO were observed for at least 18 months after the procedure (mean [SD] follow-up, 33 [14] months).

Main Outcomes and Measures

Etiology of patients with HCM who underwent surgical myectomy.

Results

From 2013, 235 consecutive patients with a clinical diagnosis of HCM underwent septal myectomy. The cardiac surgeon suspected a storage disease in 3 patients (1.3%) while inspecting their heart samples extracted from myectomy. The mean (SD) age at diagnosis for these 3 patients was 42 (4) years; all were male. None of the 3 patients presented with extracardiac features suggestive of AFC. All patients showed asymmetrical left ventricular hypertrophy, with maximal left ventricular thickness in the basal septum (19-31 mm), severe basal LVOTO (70-120 mm Hg), and left atrial dilatation (44-57 mm). Only 1 patient presented with late gadolinium enhancement on cardiovascular magnetic resonance at the right ventricle insertion site. The mean (SD) age at surgical procedure was 63 (5) years. On tactile sensation, the surgeon felt a spongy consistency of the surgical samples, different from the usual stony-elastic consistency typical of classic HCM, and this prompted histological examinations. Histology showed evidence of intracellular storage, and genetic analysis confirmed a GLA A gene mutation (p.Asn215Ser) in all 3 patients.

Conclusions and Relevance

Screening for AFC should be performed even in the absence of red flags in patients with HCM older than 25 years.

Introduction

Anderson-Fabry disease (AFD) is an X-linked lysosomal storage disease, characterized by decreased or absent activity of lysosomal α-galactosidase A due to a pathogenic mutation in the α-galactosidase A gene (GLA A). As a result of α-galactosidase A deficiency, globotriaosylceramide (GL-3) and other glycosphingolipids are stored in various tissues, including kidney, heart, and skin tissues. The diagnosis of AFD is challenging and often delayed up to 20 years following the onset of symptoms. About 70% of patients with AFD show heart involvement, including left ventricular hypertrophy (LVH), that may be severe and mimic hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM). Anderson-Fabry cardiomyopathy (AFC) is common in male patients with the specific late-onset GLA variant p.Asn215Ser. While common in HCM, resting left ventricular outflow tract obstruction (LVOTO) is rare in AFD and is more often associated with provokable gradients. Therefore, basal LVOTO in HCM is usually considered an exclusion criteria for AFC. We report a small series of severely symptomatic patients with AFD diagnosed with HCM and severe resting LVOTO who underwent surgical myectomy (SM). In each patient, the correct diagnosis was suspected intraoperatively by the cardiac surgeon and subsequently confirmed by histology and genetic analysis.

Methods

Study Population

From July 2013 to December 2016, 235 consecutive patients with a clinical diagnosis of obstructive HCM underwent SM in Policlinico di Monza, Monza, Italy, and Spitalul Hospital Monza, Bucharest, Romania, by the same senior surgeon (P.F.). In 3 patients (1.2%), the cardiac surgeon suspected a storage disease while inspecting the heart samples extracted from myectomy. The diagnosis of HCM was based on current 2014 European Society of Cardiology guidelines. Specific cardiac diagnostic red flags for HCM phenocopies were evaluated in all patients, including specific signs of AFC, such as short P-R interval or heart block, concentric LVH and right ventricular hypertrophy, or late gadolinium enhancement (LGE) on the basal posterolateral LV wall on cardiovascular magnetic resonance. Institutional review board approval was not needed for the study because it’s a report of clinical practice.

Surgical Management

Patients were preoperatively evaluated and managed following standard of care. Extended transaortic SM was performed with 2 longitudinal incisions in the basal septum 2 to 3 mm below the aortic valve and extended distally to the point of mitral septal contact, as previously described.

Histological Examinations and Genetic study

Myocardial samples collected during the surgery were examined by light microscopy following standard procedures. All patients gave informed consent for genetic analysis, which was focused on sarcomere genes associated with HCM and HCM phenocopies (PRKAG2, LAMP2, GLA, TTR, and RASopathies-related genes).

Results

Baseline Characteristics

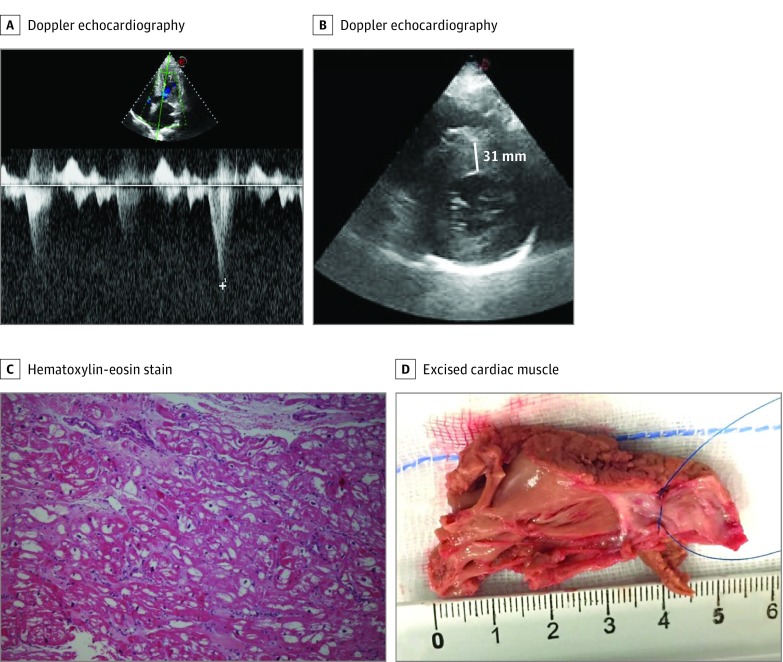

The mean (SD) age at HCM diagnosis was 42 (4) years; all were male. None of the 3 patients presented with extracardiac features suggestive of AFD. Patient 1 was diagnosed after being resuscitated from cardiac arrest, with subsequent implantable cardioverter defibrillator implantation. He had no family history of sudden cardiac death, but his brother previously received a clinical diagnosis of nonobstructive HCM (Figure 1). Patient 2 was diagnosed after syncope on exertion; family screening showed mildly obstructive HCM in the mother (aged 76 years). Patient 3 was diagnosed with HCM during routine evaluation for hypertension (Figure 1). All patients reported dyspnea and angina, and both patients 2 and 3 had a history of syncope. All were in sinus rhythm at surgery, but patients 1 and 2 had a history of paroxysmal atrial fibrillation. All patients showed diffuse and asymmetrical LVH, with maximal LV thickness in the basal septum (19-31 mm), severe basal LVOT gradients (70-120 mm Hg), and left atrial dilatation (44-57 mm) (Table) (Figure 2).

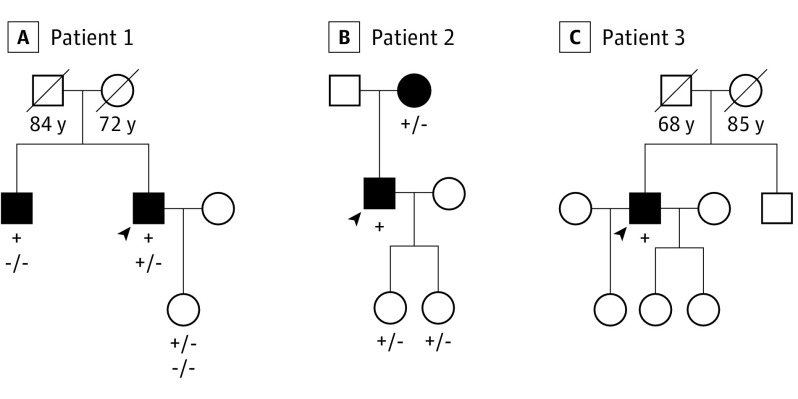

Figure 1. Family Pedigrees.

Family pedigrees of the 3 patients with Anderson-Fabry cardiomyopathy undergoing surgical myectomy. Squares represent male family members, and circles represent female family members; shading indicates affected individuals. Age at death is listed under deceased individuals. The arrowhead indicates the proband of the family. The presence of GLA A gene mutation p.Asn215Ser is listed below tested individuals. A plus sign indicates the presence of a mutated allele; a minus sign, the absence. A, The presence of MYBPC3 gene mutation p.Arg733Leu is listed below GLA A gene mutation. A plus sign indicates the presence of a mutated allele; a minus sign, the absence.

Table. Preoperative and Postoperative Clinical and Echocardiographic Characteristics of the 3 Patients.

| Characteristic | Patient 1 | Patient 2 | Patient 3 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-Op | Post-Op | Pre-Op | Post-Op | Pre-Op | Post-Op | |

| Age at myectomy, y | 67 | NA | 56 | NA | 65 | NA |

| NYHA class | III | II | III | I | III | I |

| P-R interval >200 ms | No | No | No | Yes | No | Yes |

| Sinus bradycardia | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| Bundle-branch block | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Positive Sokolov-Lyon criteria for LVH | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Atrial fibrillation | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes |

| Nonsustained VT | Yes | No | No | No | No | Yes |

| History of CAD | No | No | Yes | No | No | No |

| Aborted cardiac arrest | Yes | No | No | No | No | No |

| ICD | Yes | No | No | No | No | No |

| Ejection fraction, % | 60 | 52 | 70 | 60 | 65 | 50 |

| Left atrial dimension, mm | 57 | 56 | 44 | 34 | 47 | 47 |

| LV end-diastiolic dimension, mm | 48 | 58 | 41 | 54 | 40 | 46 |

| IVS thickness, mm | 30 | 22 | 19 | 15 | 31 | 21 |

| Posterior wall thickness, mm | 15 | 15 | 13 | 14 | 9 | 9 |

| Basal LVOT gradient, mm Hg | 100 | 15 | 70 | 14 | 120 | 0 |

| Mitral regurgitation | Mild-moderate | Mild | Mild | Mild | Moderate | Mild |

Abbreviations: CAD, coronary artery disease; ICD, implantable cardioverter defibrillator; IVS, interventricular septum; LV, left ventricular; LVH, left ventricular hypertrophy; LVOT, left ventricular outflow tract; NA, not applicable; NYHA, New York Heart Association; post-op, postoperative; pre-op, preoperative; VT, ventricular tachycardia.

Figure 2. Preoperative Echocardiographic Parameters and Postmyectomy Specimen.

A, Doppler echocardiography of left ventricular outflow tract gradient in patient 3. B, Short-axis Doppler echocardiography of left ventricular outflow tract gradient in patient 3. C, Hematoxylin-eosin stain sample from patient 1. Vacuolization of myocardial tissue is evident and constitutes a typical light microscopy marker of intracellular storage. D, Anteroposterior view of the excised cardiac muscle specimen from patient 3 (16.7 g), which shows a yellowish instead of the usual reddish color. The cardiac muscle was excised via 2 incisions in the basal septum from 2 to 3 mm below the aortic valve and extended distally to the base of the papillary muscles, creating a trapezoid trough that was wider toward the left ventricular apex than at the subaortic level.

Patient 3 showed LGE involving the right ventricular insertion site on cardiovascular magnetic resonance. No patients presented with sinus bradycardia, electrocardiographic features suggestive of AFC, or posterolateral LGE on cardiovascular magnetic resonance.

Surgical Procedures

The mean (SD) age at the time of surgery was 63 (5) years. Mean (SD) resection samples weighed 9.6 (5.2) g and were yellowish (Figure 2D). On tactile sensation, the surgeon felt a spongy consistency of the surgical samples, different from the usual stony-elastic feel typical of classic HCM, and this prompted histological examinations. The immediate postoperative course was uneventful for patients 1 and 2. Patient 3 experienced 2 self-terminating episodes of atrial fibrillation and 2 runs of nonsustained ventricular tachycardia. Mean (SD) septal thickness after surgery was 19 (3) mm compared with 27 (5) mm before surgery (Table).

Histology and Genetic Analysis

Histological examinations showed evidence of intracellular storage with prominent cytoplasmatic vacuolization of the myocytes in all patients. Genetic analysis showed the cardiac AFD variant GLA A gene mutation p.Asn215Ser in all 3 patients (Figure 1). In addition, patient 1 also had an MYBPC3 variant of unknown significance (p.Arg733Leu), which did not segregate into the family.

Clinical and Hemodynamic Benefit

All patients experienced substantial symptomatic and hemodynamic improvement after surgery (Table). At a mean (SD) postoperative follow-up of 33 (14) months, the outcome was excellent, with patients 2 and 3 reporting complete abolition of symptoms, and patient 1 improving to New York Heart Association class II. The peak basal LVOT gradient was reduced from a mean (SD) of 97 (20) mm Hg before surgery to 10 (7) mm Hg after surgery. No ventricular arrhythmias occurred, and only 1 episode of atrial fibrillation requiring electrical cardioversion was experienced by patient 1. Patients 1 and 2 refused enzyme replacement therapy, whereas patient 3 has been treated with α-galactosidase for 10 months, unassociated with further reduction in LVH.

Discussion

The diagnosis of AFD represents an important clinical challenge for the physician because of the heterogeneity of phenotypic manifestations. Anderson-Fabry cardiomyopathy has been reported in 0.5% to 2% of adult patients with HCM but up to 4% in male patients with HCM older than 40 years owing to the progressive development of LVH in men after age 25 years. The implications of a delayed or neglected diagnosis are considerable because patients are denied the opportunity of enzyme replacement therapy and cascade family screening. Cardiologists should look for specific cardiac and extracardiac signs that raise the suspicion of AFC, such as proteinuria or neuropathic pain. However, none of these may be present when the heart is the only organ involved.

We report a series of patients with AFD in whom asymmetric LVH and basal LVOTO, traditionally considered 2 exclusion criteria for AFC, were the distinctive features, in the absence of any cardiac and extracardiac red flags. Specifically, no patients presented with sinus bradycardia or electrocardiographic features suggestive of AFC, and LGE was present in only 1 patient in an atypical site for AFC. Of note, to our knowledge, SM has only been previously reported in 6 patients with symptomatic AFC, of whom 2 had provokable LVOTO and 4 had resting LVOTO. As in this series, all experienced symptomatic and hemodynamic relief after surgery, and unlike alcohol septal ablation, SM has allowed direct histological examination of the surgical specimen. To the best of our knowledge, we document for the first time a suspicion of AFC raised intraoperatively by the cardiac surgeon, based on the peculiar yellowish appearance of the myocardium and its spongy consistency and directly leading to diagnosis by subsequent histological and genetic analysis. Indeed, although up to 50% of patients with AFC may show inducible LVOTO during exercise, a small subset of patients with AFC may present with basal LVOTO.

Before surgery, none of the patients had completed genetic testing, which has a class I indication according to the 2014 European Society of Cardiology HCM guidelines. Contemporary next-generation sequencing panels for HCM should always include GLA, TTR, PRKAG2, LAMP2, and all potential phenocopies genes, including RASopathies. Indeed, sarcomeric gene mutations of unknown significance are common and may be misleading when incomplete gene panels are tested, as would have been the case in patient 1 had GLA not been tested.

Conclusions

In this consecutive surgical series, AFC prevalence was 1.2%. Features that are often—and erroneously—considered to exclude AFC, such as asymmetric LVH and resting LVOTO, may indeed be part of its phenotypic spectrum. Here, the diagnosis was suspected by the cardiac surgeon and confirmed by histological and genetic examinations. Thus, genetic screening for AFC, as part of contemporary next-generation sequencing panels including other rare HCM mimics, should be routinely performed in patients with HCM, even in the absence of cardiac and noncardiac red flags for AFC.

References

- 1.Linhart A, Kampmann C, Zamorano JL, et al. ; European FOS Investigators . Cardiac manifestations of Anderson-Fabry disease: results from the international Fabry outcome survey. Eur Heart J. 2007;28(10):1228-1235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Favalli V, Disabella E, Molinaro M, et al. . Genetic screening of Anderson-Fabry disease in probands referred from multispecialty clinics. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2016;68(10):1037-1050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wilcox WR, Oliveira JP, Hopkin RJ, et al. ; Fabry Registry . Females with Fabry disease frequently have major organ involvement: lessons from the Fabry Registry. Mol Genet Metab. 2008;93(2):112-128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Elliott P, Baker R, Pasquale F, et al. ; ACES study group . Prevalence of Anderson-Fabry disease in patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: the European Anderson-Fabry Disease Survey. Heart. 2011;97(23):1957-1960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Calcagnino M, O’Mahony C, Coats C, et al. . Exercise-induced left ventricular outflow tract obstruction in symptomatic patients with Anderson-Fabry disease. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;58(1):88-89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yousef Z, Elliott PM, Cecchi F, et al. . Left ventricular hypertrophy in Fabry disease: a practical approach to diagnosis. Eur Heart J. 2013;34(11):802-808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Elliott PM, Anastasakis A, Borger MA, et al. ; Authors/Task Force members . 2014 ESC Guidelines on diagnosis and management of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: the Task Force for the Diagnosis and Management of Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Eur Heart J. 2014;35(39):2733-2779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Iacovoni A, Spirito P, Simon C, et al. . A contemporary European experience with surgical septal myectomy in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Eur Heart J. 2012;33(16):2080-2087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ferrazzi P, Spirito P, Iacovoni A, et al. . Transaortic chordal cutting: mitral valve repair for obstructive hypertrophic cardiomyopathy with mild septal hypertrophy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2015;66(15):1687-1696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Smid BE, van der Tol L, Cecchi F, et al. . Uncertain diagnosis of Fabry disease: consensus recommendation on diagnosis in adults with left ventricular hypertrophy and genetic variants of unknown significance. Int J Cardiol. 2014;177(2):400-408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rapezzi C, Arbustini E, Caforio AL, et al. . Diagnostic work-up in cardiomyopathies: bridging the gap between clinical phenotypes and final diagnosis: a position statement from the ESC Working Group on Myocardial and Pericardial Diseases. Eur Heart J. 2013;34(19):1448-1458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kunkala MR, Aubry MC, Ommen SR, Gersh BJ, Schaff HV. Outcome of septal myectomy in patients with Fabry’s disease. Ann Thorac Surg. 2013;95(1):335-337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Geske JB, Jouni H, Aubry MC, Gersh BJ. Fabry disease with resting outflow obstruction masquerading as hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;63(17):e43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Blount JR, Wu JK, Martinez MW. Fabry’s disease with LVOT obstruction: diagnosis and management. J Card Surg. 2013;28(6):695-698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sana ME, Quilliam LA, Spitaleri A, et al. . A novel HRAS mutation independently contributes to left ventricular hypertrophy in a family with a known MYH7 mutation. PLoS One. 2016;11(12):e0168501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]