Abstract

This population-based study uses the Acute Coronary Treatment and Intervention Outcomes Network Registry to evaluate the prevalence of smoking cessation medication use among patients following myocardial infarction.

The immediate period after myocardial infarction (MI) represents a unique window of opportunity to encourage patients to quit smoking. Pharmacologic therapies, such as bupropion and varenicline, are effective and safe; however, the prevalence of their use among patients with MI in community practice is unknown.

Methods

To our knowledge, the Acute Coronary Treatment and Intervention Outcomes Network Registry is the largest MI registry in the United States; its linkage of patients older than 65 years to Medicare claims has been previously described. Among the 183 783 MI admissions between April 2007 and December 2013, 28 242 patients (15.4%) were current or recent smokers. Patients who died before discharge, were discharged to nursing homes, left against medical advice, or who were not enrolled in Part D were excluded (n = 19 049). Each hospital’s institutional review board approved participation in the registry, and the requirement for individual informed consent was waived because data were collected without individual patient identifiers.

Prescription smoking cessation medications (SCMs) included in the study were bupropion and varenicline; nicotine replacement therapies were available over the counter. Early prescription SCM use was defined as filling of a prescription within 90 days postdischarge or supply remaining from a preadmission fill. Duration of SCM use was defined as the time from the first prescription fill to the date of expected end of supply. We assessed patient factors associated with early SCM use using multivariable logistic regression modeling with forward variable selection.

Results

Among the 9193 smoking patients with MI in our cohort, 8942 patients (97%) received smoking cessation counseling during their hospitalization, yet only 647 patients (7.0%) had early-prescription SCM use (bupropion, n = 306 [47.3%] and varenicline, n = 341 [52.7%]). Varenicline use dropped from 12.6% in 2007 to 2.2% in 2013; bupropion use stayed consistently low (2.5% in 2007 and 3.2% in 2013).

The median durations of use were 6.2 weeks (25th-75th percentiles, 4.3-14.9 weeks) for bupropion and 4.3 weeks (25th-75th percentiles, 4.0-9.0 weeks) for varenicline (P < .001); only 36.7% (n = 55) and 19.7% (n = 57), respectively, filled prescriptions for the typically recommended course of 12 weeks. Within 1 year postdischarge, SCM use only increased to 9.4%. A total of 273 patients (3.0%) were taking a prescription for SCM prior to the index MI; these patients more frequently used prescription SCMs within 1 year post-MI (64.1% [n = 175 of 273] vs 7.7% [n = 690 of 8920]; P < .001).

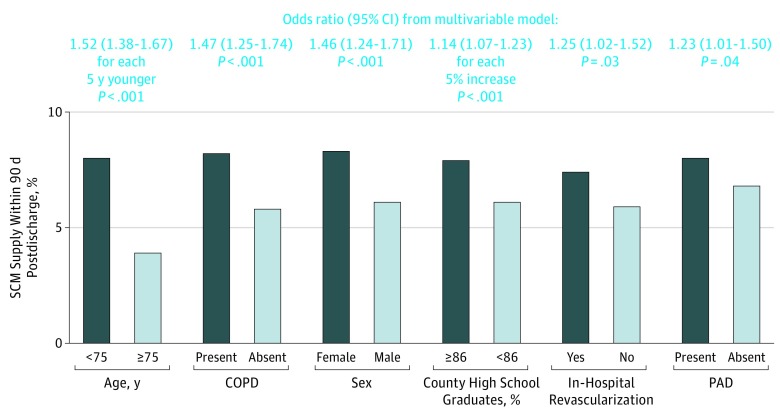

Early SCM users were more frequently younger, female, and white compared with patients who did not use prescription SCM early post-MI (Table). In multivariable modeling, race/ethnicity was no longer a significant variable, and 6 factors remained significantly associated with early SCM use (Figure). Each 5-year decrease in age was associated with a 52% (odds ratio [OR], 1.52; 95% CI, 1.38-1.67) greater likelihood of early SCM use. Additionally, patients who were women (OR, 1.46; 95% CI, 1.24-1.71) or who were living in counties with greater than the median high school graduate rate (OR, 1.14; 95% CI, 1.07-1.23) had higher likelihood of early SCM use. Patients with chronic lung disease had a 47% (OR, 1.47; 95% CI, 1.25-1.74) increased likelihood of early SCM use. Patients who underwent in-hospital coronary revascularization (OR, 1.25; 95% CI, 1.02-1.52) and those with peripheral arterial disease (OR, 1.23; 95% CI, 1.01-1.50) also had an approximately 25% higher likelihood of early SCM use.

Table. Baseline Characteristics of Patients Stratified By Early SCM Use.

| Characteristic | No. (%) | P Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall (n=9193) |

Early SCM User (n=647) |

Early SCM Nonuser (n=8546) |

||

| Demographics | ||||

| Age, median (IQR), y | 70 (67-74) | 68 (66-72) | 70 (67-74) | <.001 |

| Female sex | 4049 (44.0) | 335 (51.8) | 3714 (43.5) | <.001 |

| Nonwhite race/ethnicity | 1386 (15.1) | 71 (11.0) | 1315 (15.4) | .003 |

| Secondary insurancea | 5391 (58.6) | 374 (57.8) | 5017 (58.7) | .65 |

| Household income, median (IQR), $b | 45 129 (39 343-52 533) |

45 884 (39 821-53 686) |

45 023 (39 285-52 516) |

.06 |

| High school graduate, median (IQR)b | 86.4 (81.5-89.7) | 86.9 (82.7-90.5) | 86.4 (81.4-89.7) | .001 |

| Medical history | ||||

| Hypertension | 7194 (78.3) | 496 (76.8) | 6698 (78.4) | .33 |

| Dyslipidemia | 5951 (64.8) | 423 (65.4) | 5528 (64.7) | .74 |

| Diabetes | 2720 (29.6) | 184 (28.4) | 2536 (29.7) | .50 |

| Prior MI | 2623 (28.6) | 190 (29.5) | 2433 (28.5) | .60 |

| Prior coronary revascularizationc | 3425 (37.3) | 232 (35.9) | 3193 (37.4) | .42 |

| Prior HF | 1102 (12.0) | 65 (10.1) | 1037 (12.1) | .12 |

| Prior stroke | 882 (9.6) | 56 (8.7) | 826 (9.7) | .41 |

| Peripheral arterial disease | 1768 (19.3) | 141 (21.8) | 1627 (19.1) | .09 |

| Charlson comorbidity index, median (IQR) | 3 (2-4) | 3 (2-4) | 3 (2-4) | .86 |

| Chronic lung disease | 2985 (36.5) | 228 (44.9) | 2757 (36.0) | <.001 |

| PCP visit <1 y prior to MI | 7888 (85.8) | 571 (88.3) | 7317 (85.6) | .06 |

| In-hospital characteristics | ||||

| Transfer from another hospital | 3516 (38.2) | 262 (40.5) | 3254 (38.1) | .22 |

| STEMI | 3602 (39.2) | 265 (41.0) | 3337 (39.0) | .34 |

| Cardiogenic shock | 260 (2.8) | 13 (2.0) | 247 (2.9) | .19 |

| BMI, median (IQR) | 26.5 (23.3-30.4) | 26.1 (23.0-29.9) | 26.6 (23.4-30.5) | .22 |

| Creatinine, median (IQR), mg/dL | 1.0 (0.8-1.3) | 1.0 (0.8-1.2) | 1.0 (0.8-1.3) | .001 |

| Peak troponin, median (IQR), × ULN | 49.6 (10.3-240.0) | 45.0 (9.3-202.0) | 50.0 (10.5-244.3) | .31 |

| EF <40% | 1811 (20.8) | 119 (19.5) | 1692 (20.9) | .41 |

| In-hospital treatment | ||||

| Thrombolytic therapy (STEMI) | 358 (10.6) | 23 (9.7) | 335 (10.7) | .65 |

| PCI | 6273 (68.3) | 469 (72.5) | 5804 (68.0) | .02 |

| CABG | 688 (7.5) | 46 (7.1) | 642 (7.5) | .71 |

| Cardiac rehabilitation referrald | 6639 (78.9) | 478 (79.1) | 6161 (78.9) | .90 |

| Hospital characteristics | ||||

| Teaching hospital | 2176 (23.7) | 152 (23.6) | 2024 (23.8) | .91 |

| No. of beds, median (IQR) | 402 (260-596) | 402 (276-570) | 401 (260-602) | .69 |

| Geographic region | ||||

| South | 849 (9.2) | 63 (9.7) | 786 (9.2) | .48 |

| Midwest | 498 (5.4) | 31 (4.8) | 467 (5.5) | |

| Northeast | 2927 (31.8) | 221 (34.2) | 2706 (31.7) | |

| West | 4919 (53.5) | 332 (51.3) | 4587 (53.7) | |

| Rural hospital | 1571 (17.1) | 78 (12.1) | 1493 (17.5) | <.001 |

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index (calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared); CABG, coronary artery bypass grafting; CHF, congestive heart failure; EF, ejection fraction; HF, heart failure; IQR, interquartile range; MI, myocardial infarction; NA, not applicable; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention; PCP, primary care physician; PTA, prior to admission; SCM, smoking cessation medication; STEMI, ST elevation myocardial infarction; ULN, upper limit of normal.

SI conversion factor: To convert creatinine to micromoles per liter, multiply by 88.4.

Secondary insurance indicates additional insurance coverage (eg, private insurance) as a supplement to Medicare.

Census data based on zip code of patient residence.

Includes both prior PCI and CABG.

Cardiac rehabilitation referral proportion includes only those who were eligible for this service.

Figure. Association Between Baseline Characteristics and Smoking Cessation Medication (SCM) Supply Within 90 Days.

Prior revascularization includes both prior percutaneous coronary intervention and prior coronary artery bypass graft surgery. COPD indicates chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and PAD, peripheral arterial disease.

Discussion

Only 52.8% of patients with MI quit smoking by 1 year after the event, despite the clear benefits of smoking cessation in this population. While pharmacotherapy to assist in cessation efforts is recommended, our study shows very low rates of SCM use post-MI, and this rate has declined over time. Because individuals who successfully quit smoking do so most frequently in the immediate post-MI period, current practices indicate a missed opportunity for smoking cessation and secondary prevention efforts. Limitations of our study include the possibility of residual confounding and lack of data about actual prescription rates, smoking cessation rates post-MI, or reasons for drug prescription or discontinuation.

The results of our study suggest the need for words (smoking cessation counseling rates are high) to be followed by action (SCM use rates can be higher). Patients of older age, male sex, and lower education levels may represent key target populations for more intensive smoking cessation counseling and assistance. Our study also showed shorter duration of use compared with typically recommended courses, which suggests opportunities for further education on adherence to reduce relapses in smoking behavior.

References

- 1.Snaterse M, Scholte Op Reimer WJ, Dobber J, et al. Smoking cessation after an acute coronary syndrome: immediate quitters are successful quitters. Neth Heart J. 2015;23(12):600-607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Eisenberg MJ, Windle SB, Roy N, et al. ; EVITA Investigators . Varenicline for smoking cessation in hospitalized patients with acute coronary syndrome. Circulation. 2016;133(1):21-30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mills EJ, Thorlund K, Eapen S, Wu P, Prochaska JJ. Cardiovascular events associated with smoking cessation pharmacotherapies: a network meta-analysis. Circulation. 2014;129(1):28-41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Goyal A, de Lemos JA, Peng SA, et al. Association of patient enrollment in Medicare Part D with outcomes after acute myocardial infarction. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2015;8(6):567-575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Reeves GR, Wang TY, Reid KJ, et al. Dissociation between hospital performance of the smoking cessation counseling quality metric and cessation outcomes after myocardial infarction. Arch Intern Med. 2008;168(19):2111-2117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Siu AL; US Preventive Services Task Force . Behavioral and pharmacotherapy interventions for tobacco smoking cessation in adults, including pregnant women: US Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement. Ann Intern Med. 2015;163(8):622-634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]