Key Points

Question

Does acupuncture alone or combined with clomiphene increase the likelihood of live births among women with polycystic ovary syndrome?

Findings

In this randomized clinical trial that recruited 1000 Chinese women with polycystic ovary syndrome, the live birth rate was significantly higher in the group of women who received clomiphene compared with placebo (28.7% vs 15.4%, respectively). However, it was not significantly different between the groups who received active vs control acupuncture (21.8% vs 22.4%, respectively), and there was no significant interaction between active acupuncture and clomiphene.

Meaning

Acupuncture, alone or with clomiphene, was not effective as an infertility treatment in women with polycystic ovary syndrome.

This 2 × 2 factorial trial compared the effects of active vs sham acupuncture and of clomiphene vs placebo on live births among Chinese women with polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS).

Abstract

Importance

Acupuncture is used to induce ovulation in some women with polycystic ovary syndrome, without supporting clinical evidence.

Objective

To assess whether active acupuncture, either alone or combined with clomiphene, increases the likelihood of live births among women with polycystic ovary syndrome.

Design, Setting, and Participants

A double-blind (clomiphene vs placebo), single-blind (active vs control acupuncture) factorial trial was conducted at 21 sites (27 hospitals) in mainland China between July 6, 2012, and November 18, 2014, with 10 months of pregnancy follow-up until October 7, 2015. Chinese women with polycystic ovary syndrome were randomized in a 1:1:1:1 ratio to 4 groups.

Interventions

Active or control acupuncture administered twice a week for 30 minutes per treatment and clomiphene or placebo administered for 5 days per cycle, for up to 4 cycles. The active acupuncture group received deep needle insertion with combined manual and low-frequency electrical stimulation; the control acupuncture group received superficial needle insertion, no manual stimulation, and mock electricity.

Main Outcomes and Measures

The primary outcome was live birth. Secondary outcomes included adverse events.

Results

Among the 1000 randomized women (mean [SD] age, 27.9 [3.3] years; mean [SD] body mass index, 24.2 [4.3]), 250 were randomized to each group; a total of 926 women (92.6%) completed the trial. Live births occurred in 69 of 235 women (29.4%) in the active acupuncture plus clomiphene group, 66 of 236 (28.0%) in the control acupuncture plus clomiphene group, 31 of 223 (13.9%) in the active acupuncture plus placebo group, and 39 of 232 (16.8%) in the control acupuncture plus placebo group. There was no significant interaction between active acupuncture and clomiphene (P = .39), so main effects were evaluated. The live birth rate was significantly higher in the women treated with clomiphene than with placebo (135 of 471 [28.7%] vs 70 of 455 [15.4%], respectively; difference, 13.3%; 95% CI, 8.0% to 18.5%) and not significantly different between women treated with active vs control acupuncture (100 of 458 [21.8%] vs 105 of 468 [22.4%], respectively; difference, −0.6%; 95% CI, −5.9% to 4.7%). Diarrhea and bruising were more common in patients receiving active acupuncture than control acupuncture (diarrhea: 25 of 500 [5.0%] vs 8 of 500 [1.6%], respectively; difference, 3.4%; 95% CI, 1.2% to 5.6%; bruising: 37 of 500 [7.4%] vs 9 of 500 [1.8%], respectively; difference, 5.6%; 95% CI, 3.0% to 8.2%).

Conclusions and Relevance

Among Chinese women with polycystic ovary syndrome, the use of acupuncture with or without clomiphene, compared with control acupuncture and placebo, did not increase live births. This finding does not support acupuncture as an infertility treatment in such women.

Trial Registration

clinicaltrials.gov Identifier: NCT01573858

Introduction

Polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS), the most common cause of anovulatory infertility, is characterized by ovulatory dysfunction, hyperandrogenism, and polycystic ovaries. It is reported to affect 5% to 10% of women of reproductive age.

Clomiphene citrate is a first-line, inexpensive treatment to induce ovulation in women with PCOS. However, clomiphene had a high failure rate of 23.4% without ovulation after 5 months of use, a relatively low cumulative live birth rate of 19.1% after 5 months, and a high multiple-pregnancy rate (7.4%) among 750 women with PCOS in 2014. Thus, new or adjuvant treatments would be desirable for this population. One such treatment is acupuncture, an integral part of traditional Chinese medicine, which has gained increased popularity. There are few studies indicating the prevalence of use of acupuncture among patients seeking infertility treatment. A 2010 prevalence study from the United States including 8 community and academic infertility practices reported that 29% of their patients had used a complementary and alternative medicine treatment for infertility and 22% had tried acupuncture. Clinical trials from different countries indicate that acupuncture may improve reproductive function. However, these acupuncture trials provide insufficient evidence to determine the effectiveness of acupuncture to induce ovulation or treat infertility in PCOS because of failure to report important clinical outcomes such as live birth and limitations in quality and precision. Methodological problems include small sample size and insufficient information on allocation concealment. Thus, there is need for a multicenter randomized clinical trial on the use of acupuncture in this condition.

The PCOS Acupuncture and Clomiphene Trial (PCOSAct) investigated the effects of acupuncture and clomiphene on live births among Chinese women with PCOS.

Methods

Study Design

The PCOSAct was a randomized, multicenter, clinical trial undertaken at 21 sites (27 hospitals) in the National Clinical Trial Base of Chinese Medicine in Gynecology from mainland China. The PCOSAct was designed as a 2 × 2 factorial trial to examine the effects of active acupuncture (or control acupuncture) and clomiphene (or placebo) on live births. Details of the study design, rationale for the primary and secondary outcome measures, power analyses, and the statistical analysis plan have been previously published. The full trial protocol is available in Supplement 1. The institutional review boards at the local sites approved the protocol, and all patients together with their partners provided written informed consent before joining the study. The study was chaired by a multidisciplinary steering committee and overseen by an international data and safety monitoring board.

Participants

All patients fulfilled the diagnostic criteria for PCOS according to the modified Rotterdam criteria: oligomenorrhea or amenorrhea, together with clinical or biochemical hyperandrogenism (modified Ferriman-Gallwey hirsutism score ≥5 in Chinese), polycystic ovaries, or both. Inclusion and exclusion criteria are summarized in the eAppendix in Supplement 2. Metabolic syndrome was defined by meeting any 3 of the following 5 criteria: (1) waist circumference greater than 88 cm; (2) triglycerides level greater than 150 mg/dL (to convert to millimoles per liter, multiply by 0.0113); (3) high-density lipoprotein cholesterol level lower than 50 mg/dL (to convert to millimoles per liter, multiply by 0.0259); (4) systolic blood pressure greater than 130 mm Hg or diastolic blood pressure greater than 85 mm Hg; and (5) fasting glucose level of 110 to 126 mg/dL (to convert to millimoles per liter, multiply by 0.0555). Body mass index (BMI; calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared) was categorized as normal if less than 24, overweight if 24 or greater but less than 28, and obese if greater than 28, as defined in Chinese women. All couples agreed to have regular intercourse during the study period with the intent of conception, and patients were in good health without major medical disorders. Baseline laboratory, anthropometric, and clinical measurements including scoring of hirsutism, acne, and ultrasonography were performed after an overnight fast. All biochemical assays were performed in a core laboratory (eAppendix in Supplement 2).

Randomization and Blinding

Participants were randomly allocated in a ratio of 1:1:1:1 into 1 of 4 intervention groups: active acupuncture plus clomiphene, control acupuncture plus clomiphene, active acupuncture plus placebo, and control acupuncture plus placebo (Figure 1) by an interactive online computer program (ResMan Research Manager; http://www.medresman.org) in a central office. The randomization was stratified within 21 participating sites and defined with a random block size of 4 or 8 (concealed from the investigators) by the head of the data coordination committee (H.Z.) (eTable 1 in Supplement 2). The statisticians generated and validated the randomization scheme for the study using the Plan procedure in SAS version 9.3 software (SAS Institute, Inc). We preprinted 1000 labels with barcodes (250 per group) and affixed them to medication bottles. The bottles were distributed to sites and assigned to patients as they were enrolled. This approach ensured that the randomization was stratified by site and that there would be 250 patients per group. The clomiphene and placebo assignments were double-blinded, unknown to patients and study investigators except the data manager. The active and control acupuncture treatments were known only to acupuncturists and the data manager at each site.

Figure 1. Flow Diagram of Participants in the Polycystic Ovary Syndrome Acupuncture and Clomiphene Trial.

Immediately after randomization, there were 4 patients who conceived before the start of treatment. They completed the last visit and were included in the primary analysis.

Interventions

For a more detailed description of the study interventions, see the eAppendix in Supplement 2.

Active or Control Acupuncture

The acupuncture treatment was standardized. All patients received acupuncture treatment for 30 minutes twice weekly, with a maximum of 32 acupuncture treatments.

In the active acupuncture protocol, 2 sets of acupuncture points were alternated every other treatment to minimize soreness at the needle placement (eTable 2 and eFigure in Supplement 2). Acupuncture points were located in abdominal muscles and leg muscles (with somatic innervation common to the autonomic innervation of the ovaries and the uterus) and in the hands and head. When placed, all needles were stimulated by manual rotation until the tingling sensation called de qi was achieved. Needle sensation reflects activation of the afferent nerve fibers projecting to the central nervous system at the spinal and central levels. Needles placed in the hand and head were manually stimulated every 10 minutes. Needles in abdominal and leg muscles were manually rotated and then connected to an electrical stimulator and stimulated with low frequency.

In the control acupuncture protocol, 2 needles were inserted superficially to a depth of less than 5 mm, 1 in each shoulder and 1 in each upper arm at nonacupuncture points, and needles were not stimulated manually when inserted (eTable 2 and eFigure in Supplement 2). Thereafter, the 4 needles were attached to electrodes and the stimulator was turned on to mimic the active acupuncture but with zero intensity, ie, no electrical stimulation.

Clomiphene or Placebo

Patients started with an initial oral dose of 1 pill of clomiphene (50 mg) or placebo from days 3 to 7 of the menstrual cycle. The dosage of oral medication was increased by 1 pill in the absence of ovulation or maintained in the presence of ovulation. The maximum dosage of clomiphene or placebo did not exceed 150 mg per day or 750 mg per cycle. The treatment could be repeated for up to 4 cycles.

After the baseline visit, acupuncture treatment and clomiphene treatment were started on day 3 of a spontaneous menstrual period. In patients with irregular cycles without recent menses, withdrawal bleeding was induced by medroxyprogesterone acetate, 5 mg/d for 10 days. Patients were instructed to have regular intercourse every 2 to 3 days and were monitored weekly by urinary human chorionic gonadotropin tests and serum progesterone levels to document pregnancy and ovulation. All treatments were stopped upon a positive pregnancy test. If the patient did not conceive, all measurements were repeated after the last treatment on the third day of menstruation in an ovulatory cycle, or within 1 week after the last treatment in an anovulatory cycle. Once the patient was pregnant, treatments were stopped and the end-of-study visit was performed within 1 week. Pregnant patients were followed up by ultrasonography every second week until fetal heart motion was visible. Pregnant women were then referred to the obstetric unit and follow-up scans were performed at weeks 18 to 24, 32, and 36 or at the discretion of the obstetrician. Birth outcomes were obtained from obstetrical records.

Outcomes

The primary outcome was live birth at 20 weeks’ or later gestation during the study period. Prespecified secondary outcomes included ovulation, conception, pregnancy, pregnancy loss, multiple (twin or triplet) pregnancies, anthropometrics, hirsutism, acne, hormonal changes, quality-of-life scores, and adverse events. Treatment credibility was also a prespecified secondary outcome but is not reported in this article. Quality-of-life scores included the Polycystic Ovary Syndrome Health-Related Quality of Life Questionnaire (range of 1-7, with higher scores indicating better function), Chinese Quality of Life Instrument (range of 50-250, with higher scores indicating better function), Medical Outcomes Study 36-Item Short Form Health Survey (range of 0-100, with higher scores indicating better function), Zung Self-Rating Anxiety Scale (range of 25-100, with higher scores indicating worse anxiety), and Zung Self-Rating Depression Scale (range of 25-100, with higher scores indicating worse depression). Serious adverse events were defined as any event that was fatal or immediately life threatening; led to severe or permanent disability or required prolonged hospitalization; led to congenital anomalies; led to pregnancy loss after 12 weeks’ gestation; or was thought to be serious by the site investigators. Exploratory outcomes were singleton live births, twin live births, infant birth weight, sex ratio, pregnancy duration, singleton pregnancy, time to conception, pregnancy loss in the first trimester, pregnancy loss in the second or third trimester, biochemical pregnancy loss, and ectopic pregnancy.

Study Power

Without strong preliminary data on live birth after acupuncture, we chose 10% as the minimal clinically detectable difference that was likely to change clinical practice. We used this minimal clinically detectable difference of 10% in an earlier study. Assuming a 25% live birth rate with both active interventions, a 15% live birth rate with 1 active and 1 control intervention, and a 5% live birth rate with both control interventions, 80% power at a significance level of .05, and a 10% dropout rate, 1000 women would need to be enrolled.

Statistical Analysis

The study was designed to test 3 primary hypotheses comparing specific combinations of interventions (Supplement 1). However, a more standard approach to a factorial trial is to focus on the main effects of the 2 treatments and their interaction. That approach was more consistent with the hypothesized pattern of live birth rates used in the sample size calculation and offered greater power and precision. Therefore, although it departed from the prespecified statistical analysis plan, we performed logistic or linear regression analysis that included the main effects of the 2 interventions and the interaction between the 2 interventions. Patients who received their randomized treatment (or conceived before treatment) and completed the final visit were included in the primary analysis. Study site was included as a random effect.

Categorical variables were summarized with frequencies and percentages. Their distributions were assessed with Fisher exact test. Continuous variables were reported as means with standard deviations or medians with interquartile ranges. To simplify presentation, group means using the t test were presented because the large sample size ensured the robustness of the t test.

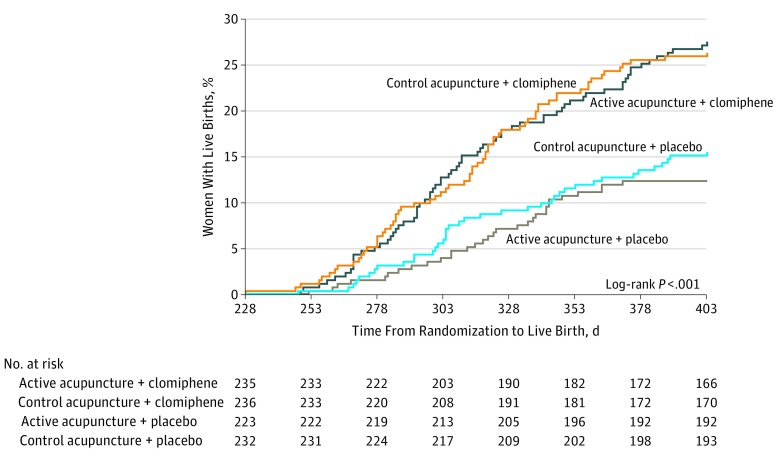

There were missing data in 74 women who withdrew and were excluded from the primary analysis. For missing data in the secondary outcomes, we specifically reported the actual sample size of each variable when it differed from the complete sample size in each intervention group. Kaplan-Meier curves were used to compare days from randomization to last live birth in the 4 groups and plotted as the cumulative incidence of live birth.

All analyses were conducted using SAS version 9.3 software (SAS Institute, Inc). Two-sided P < .05 indicated statistical significance.

Results

A total of 4645 women with PCOS were screened for eligibility; of them, 3645 were ineligible for various reasons and 1000 eligible women were randomized (250 in each group) (Figure 1). Participants were recruited from July 6, 2012, to November 18, 2014. The last live birth was recorded on October 7, 2015. Dropouts at each stage and the number assessed for the primary end point are presented in Figure 1. There was no significant difference in the dropout rates among the groups. The final visit was attended by 926 women, who composed the analytic population.

The baseline characteristics of the participants are shown in Table 1. The mean (SD) age was 27.9 (3.3) years, and the mean (SD) BMI was 24.2 (4.3). In total, 176 of 998 participants (17.7%) were obese and 196 of 999 (19.6%) met metabolic syndrome criteria. Patients had high adherence to treatment, including 849 of 926 participants (91.7%) for clomiphene and placebo and 895 of 926 (96.7%) for active or control acupuncture.

Table 1. Baseline Characteristics of Patients.

| Characteristic | Active Acupuncture + Clomiphene (n = 250)a |

Control Acupuncture + Clomiphene (n = 250)a |

Active Acupuncture + Placebo (n = 250)a |

Control Acupuncture + Placebo (n = 250)a |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Biometric features | ||||

| Age, mean (SD), y | 28.2 (3.4) | 27.8 (3.4) [249] | 27.8 (3.2) | 28.0 (3.3) [249] |

| Weight, mean (SD), kg | 62.2 (11.9) | 63.5 (11.9) [249] | 62.9 (12.8) | 64.1 (13.0) [249] |

| BMI | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 23.8 (4.2) | 24.4 (3.9) [249] | 24.2 (4.4) | 24.6 (4.5) [249] |

| ≥28, No./total No. (%) | 39/250 (15.6) | 49/249 (19.7) | 43/250 (17.2) | 45/249 (18.1) |

| Waist to hip ratio, mean (SD) | 0.9 (0.1) | 0.9 (0.1) [249] | 0.9 (0.1) [249] | 0.9 (0.1) [249] |

| Waist circumference ≥80 cm, No./total No. (%) | 156/250 (62.4) | 170/249 (68.3) | 171/250 (68.4) | 176/249 (70.7) |

| Modified Ferriman-Gallwey scoreb | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 3.0 (2.6) | 2.9 (2.6) [249] | 3.3 (3.1) | 2.9 (2.9) [249] |

| ≥5, No./total No. (%) | 68/250 (27.2) | 65/249 (26.1) | 72/250 (28.8) | 60/249 (24.1) |

| Acne score, median (IQR)c | 0 (0-1) | 0 (0-1) [249] | 0 (0-1) | 0 (0-1) [249] |

| Fertility history | ||||

| Menstrual cycles, mean (SD), No./y | 6.2 (1.9) | 6.2 (2.0) [249] | 6.3 (2.0) | 6.1 (2.3) [249] |

| Duration between menstruation periods, mean (SD), d | 69.0 (43.0) | 71.5 (49.7) [249] | 67.1 (38.6) | 70.6 (40.1) [249] |

| Time attempting to conceive, mean (SD), mo | 24.5 (17.5) [238] | 23.4 (18.7) [234] | 23.8 (17.9) [240] | 24.2 (17.2) [236] |

| Received clomiphene citrate previously, No./total No. (%) | 65/236 (27.5) | 73/239 (30.5) | 74/240 (30.8) | 68/238 (28.6) |

| Received acupuncture previously, No./total No. (%) | 23/243 (9.5) | 32/239 (13.4) | 35/246 (14.2) | 31/245 (12.7) |

| Ultrasonography findings | ||||

| Polycystic ovary morphology of any ovary, No./total No. (%) | 206/237 (86.9) | 200/236 (84.7) | 205/233 (88.0) | 215/234 (91.9) |

| Any ovarian volume ≥10 cm3, No./total No. (%) | 95/127 (74.8) | 81/122 (66.4) | 81/118 (68.6) | 80/116 (69.0) |

| Polycystic ovaries according to Rotterdam criteria, No./total No. (%)d | 222/242 (91.7) | 214/240 (89.2) | 219/237 (92.4) | 227/243 (93.4) |

| Fasting serum levels | ||||

| LH, mean (SD), mIU/mL | 10.6 (6.0) [240] | 10.0 (6.1) [242] | 10.6 (5.9) [238] | 10.8 (5.7) [237] |

| FSH, mean (SD), mIU/mL | 6.1 (1.8) [240] | 6.2 (1.5) [241] | 6.1 (1.6) [239] | 6.0 (1.7) [237] |

| LH to FSH ratio, mean (SD) | 1.8 (1.1) [240] | 1.6 (1.0) [241] | 1.8 (0.9) [238] | 1.9 (1.5) [237] |

| Progesterone, median (IQR), ng/mL | 0.54 (0.38-0.74) [238] | 0.55 (0.40-0.74) [242] | 0.56 (0.40-0.80) [238] | 0.52 (0.35-0.76) [237] |

| Estradiol, median (IQR), pg/mL | 54.59 (43.56-75.86) [240] | 53.39 (42.36-70.80) [241] | 55.28 (43.97-71.27) [240] | 52.71 (44.27-72.49) [237] |

| Total testosterone | ||||

| Mean (SD), ng/dL | 48.4 (19.2) [240] | 47.8 (18.6) [242] | 48.3 (18.3) [240] | 47.6 (18.5) [237] |

| ≥48.17 ng/dL, No./total No. (%) | 111/240 (46.3) | 113/242 (46.7) | 105/240 (43.8) | 113/237 (47.7) |

| Sex hormone–binding globulin, mean (SD), μg/mL | 4.87 (3.11) [240] | 4.87 (3.48) [241] | 4.64 (3.61) [237] | 4.77 (3.48) [236] |

| Free testosterone, mean (SD), pg/mL | 2.3 (0.8) [241] | 2.3 (0.8) [242] | 2.3 (0.9) [236] | 2.3 (0.9) [236] |

| Fasting glucose, mean (SD), mg/dL | 91.3 (15.8) [238] | 89.6 (18.3) [242] | 92.8 (17.9) [242] | 92.4 (19.3) [236] |

| Fasting insulin, mean (SD), µIU/mL | 14.2 (14.6) [240] | 13.6 (12.4) [242] | 14.4 (13.3) [240] | 13.2 (10.2) [235] |

| HOMA-IR, median (IQR)e | 2.32 (1.45-3.42) [236] | 2.15 (1.39-3.83) [240] | 2.58 (1.51-4.11) [239] | 2.35 (1.28-4.06) [234] |

| Metabolic syndrome, No./total No. (%)f | 44/250 (17.6) | 48/250 (19.2) | 51/250 (20.4) | 53/249 (21.3) |

| Triglycerides, mean (SD), mg/dL | 132.0 (74.9) [238] | 138.8 (75.9) [243] | 149.1 (91.7) [242] | 136.3 (77.9) [235] |

| Total cholesterol, mean (SD), mg/dL | 180.2 (44.9) [238] | 182.5 (41.9) [242] | 190.8 (39.8) [242] | 179.6 (41.2) [235] |

| HDL-C, mean (SD), mg/dL | 50.1 (15.1) [238] | 48.4 (14.6) [242] | 49.6 (12.9) [242] | 48.9 (14.7) [236] |

| LDL-C, mean (SD), mg/dL | 111.9 (35.9) [238] | 114.5 (33.3) [243] | 119.6 (32.3) [241] | 112.1 (33.1) [235] |

| Total score on quality-of-life measures, mean (SD) | ||||

| PCOSQg | 4.4 (1.0) | 4.4 (1.0) [249] | 4.4 (1.0) | 4.4 (1.1) [249] |

| ChiQOLh | 181.5 (22.5) | 179.5 (22.4) [249] | 178.5 (21.1) | 180.1 (21.2) [249] |

| SF-36i | 78.0 (12.6) | 77.6 (12.5) [249] | 77.0 (11.7) | 78.2 (12.3) [249] |

| SASj | 42.0 (8.9) | 42.5 (8.7) [249] | 42.6 (8.4) | 42.4 (8.4) [249] |

| SDSk | 43.7 (11.0) | 44.4 (10.6) [249] | 44.7 (10.5) | 44.6 (9.9) [249] |

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index (calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared); ChiQOL, Chinese Quality of Life Instrument; FSH, follicle-stimulating hormone; HDL-C, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol; HOMA-IR, homeostatic model assessment–insulin resistance; IQR, interquartile range; LDL-C, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol; LH, luteinizing hormone; PCOSQ, Polycystic Ovary Syndrome Health-Related Quality of Life Questionnaire; SAS, Zung Self-Rating Anxiety Scale; SDS, Zung Self-Rating Depression Scale; SF-36, 36-Item Short Form Health Survey.

SI conversion factors: To convert LH and FSH to IU/L, multiply by 1.0; progesterone to nmol/L, multiply by 3.18; estradiol to pmol/L, multiply by 3.671; total testosterone to nmol/L, multiply by 0.0347; sex hormone–binding globulin to nmol/L, multiply by 8.896; free testosterone to nmol/L, multiply by 0.0000347; glucose to mmol/L, multiply by 0.0555; insulin to pmol/L, multiply by 6.945; triglycerides to mmol/L, multiply by 0.0113; and total cholesterol, HDL-C, and LDL-C to mmol/L, multiply by 0.0259.

For variables expressed as mean (SD) or median (IQR) with sample sizes that differ from the complete sample in the intervention group, the sample sizes are indicated in brackets.

Scores on the modified Ferriman-Gallwey scale for hirsutism range from 0 to 44, with higher scores indicating a greater degree of hirsutism.

Scores on the acne scale range from 0 to 5, with higher scores indicating a greater degree of acne.

Polycystic ovaries were defined by an antral follicle count of 12 or more or by a volume of more than 10 cm3 in at least 1 ovary.

The HOMA-IR values were calculated according to the following formula: (fasting plasma glucose in millimoles per liter × fasting insulin in micro–international units per milliliter)/22.5.

Metabolic syndrome was defined by meeting any 3 of the following 5 criteria: (1) waist circumference greater than 88 cm; (2) triglycerides level greater than 150 mg/dL; (3) HDL-C level lower than 50 mg/dL; (4) systolic blood pressure greater than 130 mm Hg or diastolic blood pressure greater than 85 mm Hg; and (5) fasting glucose level of 110 to 126 mg/dL.

Scores on the PCOSQ, a questionnaire for measuring health-related quality of life in women with polycystic ovary syndrome, range from 1 to 7, with higher scores indicating better function.

Scores range from 50 to 250, with higher scores indicating better function.

Scores on the SF-36, a generic health-related quality-of-life measure, range from 0 to 100, with higher scores indicating better function.

Scores range from 25 to 100, with higher scores indicating more severe anxiety.

Scores range from 25 to 100, with higher scores indicating more severe depression.

Primary Outcome

There were 69 live births (29.4%) in 235 patients receiving active acupuncture plus clomiphene, 66 (28.0%) in 236 patients with control acupuncture plus clomiphene, 31 (13.9%) in 223 patients with active acupuncture plus placebo, and 39 (16.8%) in 232 patients with control acupuncture plus placebo (Figure 2). There was no significant interaction on live births between clomiphene and active acupuncture (P = .39); therefore, the main effects of clomiphene and acupuncture were examined. The live birth rate was significantly higher in the group of women treated with clomiphene than among those who received placebo (135 of 471 [28.7%] vs 70 of 455 [15.4%]; difference, 13.3%; 95% CI, 8.0% to 18.5%) but was not significantly different between the groups treated with active and control acupuncture (100 of 458 [21.8%] vs 105 of 468 [22.4%]; difference, −0.6%; 95% CI, −5.9% to 4.7%) (Table 2).

Figure 2. Kaplan-Meier Curves for Cumulative Live Births Following Randomization.

The first live birth occurred 228 days after randomization, and the last live birth occurred 403 days after randomization.

Table 2. Outcomes With Regard to Live Birth, Conception, Pregnancy, Pregnancy Loss, and Ovulation.

| Outcomea | No./Total No. (%) | Absolute Difference (95% CI)b | P Value for Interactioni | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Active Acupuncture + Clomiphene (n = 235) |

Control Acupuncture + Clomiphene (n = 236) |

Active Acupuncture + Placebo (n = 223) |

Control Acupuncture + Placebo (n = 232) |

Effect of Active Acupuncture | Effect of Clomiphene | ||||||

| Plus Clomiphenec | Plus Placebod | Overalle | Plus Active Acupuncturef | Plus Control Acupunctureg | Overallh | ||||||

| Primary outcome | |||||||||||

| Live births among all women | 69/235 (29.4) | 66/236 (28.0) | 31/223 (13.9) | 39/232 (16.8) | 1.4 (−6.8 to 9.6) | −2.9 (−9.5 to 3.7) | −0.6 (−5.9 to 4.7) | 15.5 (8.1 to 22.8) | 11.2 (3.7 to 18.6) | 13.3 (8.0 to 18.5) | .39 |

| Secondary outcomes | |||||||||||

| Conception among all women | 108/235 (46.0) | 106/236 (44.9) | 51/223 (22.9) | 55/232 (23.7) | 1.0 (−8.0 to 10.0) | −0.8 (−8.6 to 6.9) | 0.3 (−5.8 to 6.4) | 23.1 (14.7 to 31.5) | 21.2 (12.8 to 29.6) | 22.1 (16.2 to 28.1) | .76 |

| Pregnancy among all women | 74/235 (31.5) | 70/236 (29.7) | 33/223 (14.8) | 41/232 (17.7) | 1.8 (−6.5 to 10.1) | −2.9 (−9.6 to 3.9) | −0.4 (−5.8 to 5.1) | 16.7 (9.1 to 24.2) | 12.0 (4.4 to 19.6) | 14.3 (8.9 to 19.7) | .37 |

| Twin pregnancy among all pregnancies | 7/74 (9.5) | 6/70 (8.6) | 0/33 | 2/41 (4.9) | 0.9 (−8.5 to 10.2) | −4.9 (−11.5 to 1.7) | −0.7 (−7.4 to 6.1) | 9.5 (2.8 to 16.1) | 3.7 (−5.6 to 13.0) | 6.3 (0.4 to 12.3) | .36 |

| Pregnancy loss among women who conceived | 38/108 (35.2) | 37/106 (34.9) | 19/51 (37.3) | 16/55 (29.1) | 0.3 (−12.5 to 13.1) | 8.2 (−9.7 to 26.1) | 2.9 (−7.5 to 13.3) | −2.1 (−18.1 to 14.0) | 5.8 (−9.2 to 20.9) | 2.0 (−9.0 to 13.0) | .51 |

| Ovulation among all women | 221/235 (94.0) | 218/236 (92.4) | 156/223 (70.0) | 162/232 (69.8) | 1.7 (−2.9 to 6.2) | 0.1 (−8.3 to 8.6) | 1.1 (−3.9 to 6.1) | 24.1 (17.4 to 30.8) | 22.5 (15.7 to 29.4) | 23.3 (18.5 to 28.1) | .55 |

| Ovulation per cycle | 511/777 (65.8) | 519/784 (66.2) | 275/818 (33.6) | 294/863 (34.1) | −0.4 (−5.1 to 4.3) | −0.4 (−5.0 to 4.1) | −0.1 (−3.5 to 3.4) | 32.1 (27.5 to 36.8) | 32.1 (27.6 to 36.7) | 32.1 (28.9 to 35.4) | .97 |

Live birth was defined as the delivery of a live-born infant (≥20 weeks’ gestation). Conception was defined as any positive serum level of human chorionic gonadotropin. Pregnancy was defined as an intrauterine pregnancy with fetal heart motion, as determined by ultrasonography. There were no triple or higher-order pregnancies except twin pregnancies in this trial. Ovulation was defined as a serum progesterone level according to the standard of the local site laboratory (minimum value of luteal phase).

Differences are expressed as percentage points for 6 comparisons by factorial design.

Active acupuncture plus clomiphene vs control acupuncture plus clomiphene.

Active acupuncture plus placebo vs control acupuncture plus placebo.

Acupuncture main effect: (active acupuncture plus clomiphene) + (active acupuncture plus placebo) vs (control acupuncture plus clomiphene) + (control acupuncture plus placebo).

Active acupuncture plus clomiphene vs active acupuncture plus placebo.

Control acupuncture plus clomiphene vs control acupuncture plus placebo.

Clomiphene main effect: (active acupuncture plus clomiphene) + (control acupuncture plus clomiphene) vs (active acupuncture plus placebo) + (control acupuncture plus placebo).

P values of the interaction between active acupuncture and clomiphene treatments.

Secondary Outcomes

For the secondary outcomes, the interaction between the 2 interventions was not statistically significant except for the adverse event of back pain. Statistically significant results are discussed herein.

The rates of ovulation, conception, pregnancy, and multiple pregnancy were significantly different between patients treated with clomiphene vs placebo but not significantly different between those receiving active vs control acupuncture. Differences in the effects of clomiphene vs placebo (Table 2) were 32.1% (95% CI, 28.9% to 35.4%) in ovulation rate per cycle (1030 of 1561 [66.0%] vs 569 of 1681 [33.8%]), 23.3% (95% CI, 18.5% to 28.1%) in ovulation rate per woman (439 of 471 [93.2%] vs 318 of 455 [69.9%]), 22.1% (95% CI, 16.2% to 28.1%) in conception rate (214 of 471 [45.4%] vs 106 of 455 [23.3%]), and 14.3% (95% CI, 8.9% to 19.7%) in pregnancy rate (144 of 471 [30.6%] vs 74 of 455 [16.3%]).

The frequency of serious adverse events was very low and did not differ significantly among the groups (Table 3). There were 72 serious adverse events reported. Abnormal vaginal bleeding was less common in patients receiving clomiphene vs placebo (10 of 500 [2.0%] vs 47 of 500 [9.4%]; difference, −7.4%; 95% CI, −10.2% to −4.6%), but dysmenorrhea was more common in patients receiving clomiphene vs placebo (13 of 500 [2.6%] vs 3 of 500 [0.6%]; difference, 2.0%; 95% CI, 0.4% to 3.6%). Patients receiving active acupuncture compared with those receiving control acupuncture more commonly had bruising (37 of 500 [7.4%] vs 9 of 500 [1.8%]; difference, 5.6%; 95% CI, 3.0% to 8.2%) and diarrhea (25 of 500 [5.0%] vs 8 of 500 [1.6%]; difference, 3.4%; 95% CI, 1.2% to 5.6%).

Table 3. All Serious Adverse Events, Plus Adverse Events of Most Common or Significant Differences Among the Treatment Groups.

| Outcome | No./Total No. (%) | Absolute Difference (95% CI)a | P Value for Interactionh | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Active Acupuncture + Clomiphene (n = 250) |

Control Acupuncture + Clomiphene (n = 250) |

Active Acupuncture + Placebo (n = 250) |

Control Acupuncture + Placebo (n = 250) |

Effect of Active Acupuncture | Effect of Clomiphene | ||||||

| Plus Clomipheneb | Plus Placeboc | Overalld | Plus Active Acupuncturee | Plus Control Acupuncturef | Overallg | ||||||

| Before conception among women who received a study drug | (n = 250) | (n = 250) | (n = 250) | (n = 250) | |||||||

| Serious adverse event | |||||||||||

| Liver dysfunction | 1 (0.4)i | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.4 (−0.4 to 1.2) | NA | 0.2 (−0.2 to 0.6) | 0.4 (−0.4 to 1.2) | NA | 0.2 (−0.2 to 0.6) | .67 |

| Fracture of coccyx | 1 (0.4) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.4 (−0.4 to 1.2) | NA | 0.2 (−0.2 to 0.6) | 0.4 (−0.4 to 1.2) | NA | 0.2 (−0.2 to 0.6) | .67 |

| Hyperplasia of mammary glands | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (0.4)j | NA | −0.4 (−1.2 to 0.4) | −0.2 (−0.6 to 0.2) | NA | −0.4 (−1.2 to 0.4) | −0.2 (−0.6 to 0.2) | .67 |

| Adverse event | |||||||||||

| Abnormal vaginal bleeding | 2 (0.8) | 8 (3.2) | 22 (8.8) | 25 (10.0) | −2.4 (−4.8 to 0.0) | −1.2 (−6.3 to 3.9) | −1.8 (−4.7 to 1.1) | −8.0 (−11.7 to −4.3) | −6.8 (−11.1 to −2.5) | −7.4 (−10.2 to −4.6) | .15 |

| Diarrhea | 9 (3.6) | 3 (1.2) | 16 (6.4) | 5 (2.0) | 2.4 (−0.3 to 5.1) | 4.4 (0.9 to 7.9) | 3.4 (1.2 to 5.6) | −2.8 (−6.6 to 1.0) | −0.8 (−3.0 to 1.4) | −1.8 (−4.0 to 0.4) | .92 |

| Dysmenorrhea | 9 (3.6) | 4 (1.6) | 2 (0.8) | 1 (0.4) | 2.0 (−0.8 to 4.8) | 0.4 (−1.0 to 1.8) | 1.2 (−0.4 to 2.8) | 2.8 (0.2 to 5.4) | 1.2 (−0.5 to 2.9) | 2.0 (0.4 to 3.6) | .92 |

| Bruising | 14 (5.6) | 1 (0.4) | 23 (9.2) | 8 (3.2) | 5.2 (2.2 to 8.2) | 6.0 (1.8 to 10.2) | 5.6 (3.0 to 8.2) | −3.6 (−8.2 to 1.0) | −2.8 (−5.1 to −0.5) | −3.2 (−5.8 to −0.6) | .19 |

| After conception among conceptions | (n = 108) | (n = 106) | (n = 51) | (n = 55) | |||||||

| First trimester | |||||||||||

| Serious adverse event | |||||||||||

| Ectopic pregnancy | 1 (0.9) | 2 (1.9) | 1 (2.0) | 0 | −1.0 (−4.1 to 2.2) | 2.0 (−1.8 to 5.8) | 0.0 (−2.4 to 2.5) | −1.0 (−5.2 to 3.2) | 1.9 (−0.7 to 4.5) | 0.5 (−2.0 to 2.9) | .38 |

| Hydatidiform mole | 0 | 1 (0.9) | 0 | 0 | −0.9 (−2.8 to 0.9) | NA | −0.6 (−1.8 to 0.6) | NA | 0.9 (−0.9 to 2.8) | 0.5 (−0.4 to 1.4) | .65 |

| Adverse event | |||||||||||

| Back pain | 1 (0.9) | 8 (7.5) | 3 (5.9) | 1 (1.8) | −6.6 (−12.0 to −1.3) | 4.1 (−3.3 to 11.4) | −3.1 (−7.4 to 1.2) | −5.0 (−11.7 to 1.7) | 5.7 (−0.4 to 11.9) | 0.4 (−4.1 to 4.9) | .05 |

| Threatened abortionk | 25 (23.1) | 25 (23.6) | 13 (25.5) | 17 (30.9) | −0.4 (−11.8 to 10.9) | −5.4 (−22.5 to 11.7) | −2.2 (−11.7 to 7.3) | −2.3 (−16.7 to 12.0) | −7.3 (−22.0 to 7.3) | −4.9 (−15.2 to 5.3) | .52 |

| Second and third trimesters | |||||||||||

| Serious adverse event | |||||||||||

| Incompetent cervix | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (1.8) | NA | −1.8 (−5.3 to 1.7) | −0.6 (−1.8 to 0.6) | NA | −1.8 (−5.3 to 1.7) | −0.9 (−2.8 to 0.9) | .70 |

| Late abortion | 2 (1.9) | 3 (2.8) | 0 | 1 (1.8) | −1.0 (−5.0 to 3.1) | −1.8 (−5.3 to 1.7) | −1.2 (−4.2 to 1.7) | 1.9 (−0.7 to 4.4) | 1.0 (−3.7 to 5.7) | 1.4 (−1.3 to 4.1) | .72 |

| Severe preeclampsia | 1 (0.9) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.9 (−0.9 to 2.7) | NA | 0.6 (−0.6 to 1.9) | 0.9 (−0.9 to 2.7) | NA | 0.5 (−0.4 to 1.4) | .70 |

| Congenital anomaly | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (1.8)l | NA | −1.8 (−5.3 to 1.7) | −0.6 (−1.8 to 0.6) | NA | −1.8 (−5.3 to 1.7) | −0.9 (−2.8 to 0.9) | .70 |

| Placenta previa | 1 (0.9) | 1 (0.9) | 2 (3.9) | 1 (1.8) | 0.0 (−2.6 to 2.6) | 2.1 (−4.3 to 8.5) | 0.6 (−2.1 to 3.4) | −3.0 (−8.6 to 2.6) | −0.9 (−4.9 to 3.1) | −1.9 (−5.3 to 1.5) | .69 |

| Placental abruption | 1 (0.9) | 0 | 0 | 1 (1.8) | 0.9 (−0.9 to 2.7) | −1.8 (−5.3 to 1.7) | 0.0 (−1.7 to 1.7) | 0.9 (−0.9 to 2.7) | −1.8 (−5.3 to 1.7) | −0.5 (−2.5 to 1.6) | .36 |

| Preterm labor | 6 (5.6) | 5 (4.7) | 1 (2.0) | 5 (9.1) | 0.8 (−5.1 to 6.8) | −7.1 (−15.6 to 1.4) | −1.8 (−6.7 to 3.1) | 3.6 (−2.2 to 9.4) | −4.4 (−13.0 to 4.2) | −0.5 (−5.8 to 4.8) | .17 |

| Gestational diabetes mellitus | 5 (4.6) | 8 (7.5) | 3 (5.9) | 4 (7.3) | −2.9 (−9.3 to 3.5) | −1.4 (−10.8 to 8.0) | −2.4 (−7.7 to 2.9) | −1.3 (−8.8 to 6.3) | 0.3 (−8.2 to 8.8) | −0.5 (−6.2 to 5.2) | .77 |

| Adverse event | |||||||||||

| Upper respiratory tract infection | 19 (17.6) | 18 (17.0) | 11 (21.6) | 7 (12.7) | 0.6 (−9.5 to 10.7) | 8.8 (−5.5 to 23.2) | 3.3 (−4.9 to 11.6) | −4.0 (−17.4 to 9.4) | 4.3 (−7.1 to 15.6) | 0.3 (−8.5 to 9.1) | .36 |

| Back pain | 22 (20.4) | 12 (11.3) | 2 (3.9) | 10 (18.2) | 9.0 (−0.6 to 18.7) | −14.3 (−25.8 to −2.8) | 1.4 (−6.3 to 9.1) | 16.4 (7.2 to 25.7) | −6.9 (−18.7 to 5.0) | 4.6 (−3.2 to 12.3) | .02 |

| Edema | 30 (27.8) | 28 (26.4) | 11 (21.6) | 12 (21.8) | 1.4 (−10.5 to 13.3) | −0.2 (−16.0 to 15.5) | 0.9 (−8.6 to 10.5) | 6.2 (−7.9 to 20.3) | 4.6 (−9.2 to 18.4) | 5.4 (−4.4 to 15.3) | .89 |

| Antepartum hemorrhage | 8 (7.4) | 4 (3.8) | 5 (9.8) | 3 (5.5) | 3.6 (−2.5 to 9.8) | 4.3 (−5.8 to 14.5) | 3.8 (−1.5 to 9.1) | −2.4 (−11.9 to 7.1) | −1.7 (−8.7 to 5.3) | −1.9 (−7.8 to 4.0) | .89 |

| Delivery and postpartum among conceptions | (n = 108) | (n = 106) | (n = 51) | (n = 55) | |||||||

| Postpartum hemorrhage | 0 | 2 (1.9) | 0 | 1 (1.8) | −1.9 (−4.5 to 0.7) | −1.8 (−5.3 to 1.7) | −1.9 (−4.0 to 0.2) | NA | 0.1 (−4.3 to 4.4) | 0.0 (−2.3 to 2.2) | .80 |

| After 20 wk of gestation in fetus through neonatal period in infant among live births | (n = 69) | (n = 66) | (n = 31) | (n = 39) | |||||||

| Serious adverse event | |||||||||||

| Neonatal death | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 (5.1)m | NA | −5.1 (−12.1 to 1.8) | −1.9 (−4.5 to 0.7) | NA | −5.1 (−12.1 to 1.8) | −2.9 (−6.8 to 1.0) | .59 |

| Congenital anomaly | 1 (1.4)n | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1.4 (−1.4 to 4.3) | NA | 1.0 (−1.0 to 3.0) | 1.4 (−1.4 to 4.3) | NA | 0.7 (−0.7 to 2.2) | .75 |

| Neonatal pneumonia | 0 | 1 (1.5) | 0 | 0 | −1.5 (−4.5 to 1.4) | NA | −1.0 (−2.8 to 0.9) | NA | 1.5 (−1.4 to 4.5) | 0.7 (−0.7 to 2.2) | .60 |

| Neonatal hydronephrosis | 0 | 1 (1.5) | 0 | 0 | −1.5 (−4.5 to 1.4) | NA | −1.0 (−2.8 to 0.9) | NA | 1.5 (−1.4 to 4.5) | 0.7 (−0.7 to 2.2) | .60 |

| Neonatal hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy | 0 | 2 (3.0) | 0 | 1 (2.6) | NA | −2.6 (−7.5 to 2.4) | −2.9 (−6.0 to 0.3) | NA | 0.5 (−6.0 to 6.9) | 0.1 (−3.4 to 3.5) | .73 |

| Neonatal herpes | 0 | 0 | 1 (3.2) | 0 | NA | 3.2 (−3.0 to 9.4) | 1.0 (−1.0 to 3.0) | −3.2 (−9.4 to 3.0) | NA | −1.4 (−4.2 to 1.4) | .60 |

| Adverse event | |||||||||||

| Neonatal pneumonia | 0 | 2 (3.0) | 3 (9.7) | 0 | −3.0 (−7.2 to 1.1) | 9.7 (−0.7 to 20.1) | 1.1 (−3.1 to 5.3) | −9.7 (−20.1 to 0.7) | 3.0 (−1.1 to 7.2) | −2.8 (−8.0 to 2.4) | .07 |

| Neonatal jaundice | 6 (8.7) | 3 (4.5) | 5 (16.1) | 4 (10.3) | 4.2 (−4.2 to 12.5) | 5.9 (−10.2 to 21.9) | 4.3 (−3.4 to 12.1) | −7.4 (−22.0 to 7.1) | −5.7 (−16.5 to 5.1) | −6.2 (−15.1 to 2.7) | .87 |

Abbreviation: NA, not available.

Differences are expressed as percentage points for 6 comparisons by factorial design.

Active acupuncture plus clomiphene vs control acupuncture plus clomiphene.

Active acupuncture plus placebo vs control acupuncture plus placebo.

Acupuncture main effect: (active acupuncture plus clomiphene) + (active acupuncture plus placebo) vs (control acupuncture plus clomiphene) + (control acupuncture plus placebo).

Active acupuncture plus clomiphene vs active acupuncture plus placebo.

Control acupuncture plus clomiphene vs control acupuncture plus placebo.

Clomiphene main effect: (active acupuncture plus clomiphene) + (control acupuncture plus clomiphene) vs (active acupuncture plus placebo) + (control acupuncture plus placebo).

P values of the interaction between active acupuncture and clomiphene treatments.

One woman had liver dysfunction with positive Epstein-Barr virus; she was hospitalized to receive medication, and she recovered later.

One woman was hospitalized for hyperplasia of mammary glands by ultrasonography; she developed a mass, which was removed surgically. Pathological analysis showed ductal papillary tumor.

Defined as appearance of bloody vaginal discharge or bleeding through a closed cervical os during the first half of pregnancy.

One infant had a lymphocyst.

In total, there were 4 neonatal deaths, ie, with loss of both twins.

One infant had neonatal right talipes valgus during cesarean delivery.

During pregnancy, back pain was reported less frequently in patients receiving active acupuncture plus clomiphene than in those receiving control acupuncture plus clomiphene in the first trimester (1 of 108 [0.9%] vs 8 of 106 [7.5%]; difference, −6.6%; 95% CI, −12.0% to −1.3%) and less frequently in patients receiving active acupuncture plus placebo than in those receiving control acupuncture plus placebo in the second and third trimesters (2 of 51 [3.9%] vs 10 of 55 [18.2%]; difference, −14.3%; 95% CI, −25.8% to −2.8%). Clomiphene was more frequently associated with back pain in patients receiving active acupuncture plus clomiphene than in those receiving active acupuncture plus placebo in the second and third trimesters (22 of 108 [20.4%] vs 2 of 51 [3.9%]; difference, 16.4%; 95% CI, 7.2% to 25.7%). The most common adverse events were gestational diabetes mellitus and preterm labor. Two congenital anomalies were reported. Four newborn deaths were reported from 2 preterm twin deliveries in the group that received control acupuncture plus placebo.

Significantly greater increases in circulating levels of progesterone, total testosterone, estradiol, and sex hormone–binding globulin were found in women receiving clomiphene vs placebo, and these levels were not significantly different between women receiving active vs control acupuncture. The hormone results are presented in eTable 3 in Supplement 2.

There were no significant changes in quality of life among the 4 groups (eTable 4 in Supplement 2).

Exploratory Outcomes

For the exploratory outcomes, the interaction between the 2 interventions was not statistically significant except for duration of pregnancy. Clomiphene was associated with higher rates of conception, single and twin pregnancies, and single and twin live births among women who ovulated compared with placebo. Active acupuncture compared with control acupuncture was not significantly associated with differences in rates of ovulation, conception, pregnancy, and twin pregnancy. Neither treatment was associated with newborn weight, sex ratio of boys to girls, or pregnancy loss among groups. Other exploratory outcomes are shown in eTable 5 in Supplement 2.

Discussion

This trial found that clomiphene was superior to placebo for achieving live births among infertile women with PCOS and that active acupuncture provided no additional benefit over control acupuncture. Secondary outcomes of ovulation and pregnancy were more likely to occur after treatment with clomiphene than with placebo, but not with active acupuncture vs control acupuncture. These findings do not support acupuncture alone or combined with clomiphene as an infertility treatment in patients with PCOS.

A Cochrane review found insufficient evidence for active acupuncture compared with control acupuncture to treat anovulation and infertility in women with PCOS. Before this study, 2 trials demonstrated that acupuncture was effective for ovulation induction compared with no treatment or regularly meeting with a therapist. The only sham-controlled trial using a nonpenetrating sham was underpowered for investigating live births, but it found ovulation rates between active and control acupuncture similar to those observed in this study. That study used the nonpenetrating Streitberger placebo needle, whereas superficial needle placement was used as a control in this study. Both control situations involved fewer needles and placement away from the active acupuncture needle placement sites.

The appropriate control group in acupuncture trials is debated because the nonpenetrating and superficial acupuncture needle techniques are not completely inert. The ovulation rates in the active and control acupuncture groups in this trial were higher than rates in trials with a no-intervention control group. Thus, the acupuncture procedure, unrelated to needle placement or stimulation, may have placebo effects.

There was no statistically significant difference between active and control acupuncture in clinical or biochemical variables or serious adverse events. There were 2 congenital anomalies. The incidence was similar to recent trials evaluating the effectiveness of clomiphene, metformin, letrozole, or berberine for live births in women with PCOS. Although 4 neonatal deaths occurred, these were in the group receiving control treatments and were due to the loss of 2 preterm twin pregnancies. Patients receiving active acupuncture had a higher incidence of skin bruising and diarrhea compared with control acupuncture. However, back pain during pregnancy was less frequent in the active acupuncture groups.

Clomiphene is the first-line choice for ovulation induction for anovulatory infertility in PCOS. The ovulation rate per cycle with clomiphene seems not to be affected by ethnicity or race, although obesity has a negative effect. In previous studies, ovulation rates have been 49.0% in obese white women, 56.2% in lean or overweight Indian women, and 59.0% in obese Malaysian women, compared with 66.0% in the Chinese women with a mean BMI of 24.2 in this study.

Pregnancy loss in the control acupuncture and clomiphene group was 34.9%. The pregnancy loss was higher than in other large multicenter trials in women with PCOS, ie, 25.8% in the PPCOS I study and 29.1% in the PPCOS II study. The reason may be increased detection of early conception with subsequent biochemical pregnancies or early pregnancy loss in this trial.

Strengths of this study include the factorial design, adequate power, similar withdrawal rates among groups, and high adherence to treatment.

This study had several limitations. One limitation was the fixed acupuncture protocol. Personalized acupuncture treatment might have been more effective. In traditional Chinese medicine, acupuncture is often combined with individualized herbal mixtures, which were prohibited in the protocol to avoid confounding. Another limitation is the deviation of the statistical approach with factorial analysis from the serial 2-way comparisons that were prespecified in the protocol.

Conclusions

Among Chinese women with PCOS, the use of acupuncture with or without clomiphene, compared with control acupuncture and placebo, did not increase live births. This finding does not support acupuncture as an infertility treatment in such women.

Trial Protocol

eAppendix. Supplemental Methods

eReferences

eFigure. Acupuncture Point Localization in the Active Acupuncture and Control Acupuncture Groups

eTable 1. Distribution of Number of Patients by Site and Treatment Arm

eTable 2. Acupuncture Points, Stimulation, Localization, Tissue in Which Needles Are Inserted, and Innervation Area in Active Acupuncture, Which Consists of Two Protocols That Are Alternated Every Other Treatment, and Control Acupuncture

eTable 3. Secondary Reproductive and Metabolic Outcome Changes From Baseline to Last Visit Measures

eTable 4. Secondary Quality-of-Life Outcomes Score Changes From Baseline to Last Visit Measures

eTable 5. Exploratory Outcomes With Regard to Fecundity

References

- 1.Rotterdam ESHRE/ASRM-Sponsored PCOS Consensus Workshop Group Revised 2003 consensus on diagnostic criteria and long-term health risks related to polycystic ovary syndrome. Fertil Steril. 2004;81(1):19-25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Li R, Zhang Q, Yang D, et al. Prevalence of polycystic ovary syndrome in women in China: a large community-based study. Hum Reprod. 2013;28(9):2562-2569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Legro RS, Barnhart HX, Schlaff WD, et al. ; Cooperative Multicenter Reproductive Medicine Network . Clomiphene, metformin, or both for infertility in the polycystic ovary syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2007;356(6):551-566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Legro RS, Brzyski RG, Diamond MP, et al. ; NICHD Reproductive Medicine Network . Letrozole versus clomiphene for infertility in the polycystic ovary syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2014;371(2):119-129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Thessaloniki ESHRE/ASRM-Sponsored PCOS Consensus Workshop Group Consensus on infertility treatment related to polycystic ovary syndrome. Fertil Steril. 2008;89(3):505-522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lim CE, Ng RW, Xu K, et al. Acupuncture for polycystic ovarian syndrome. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;5(5):CD007689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Smith JF, Eisenberg ML, Millstein SG, et al. ; Infertility Outcomes Program Project Group . The use of complementary and alternative fertility treatment in couples seeking fertility care: data from a prospective cohort in the United States. Fertil Steril. 2010;93(7):2169-2174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pastore LM, Williams CD, Jenkins J, Patrie JT. True and sham acupuncture produced similar frequency of ovulation and improved LH to FSH ratios in women with polycystic ovary syndrome. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2011;96(10):3143-3150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bovey M, Lorenc A, Robinson N. Extent of acupuncture practice for infertility in the United Kingdom: experiences and perceptions of the practitioners. Fertil Steril. 2010;94(7):2569-2573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Read SC, Carrier ME, Whitley R, Gold I, Tulandi T, Zelkowitz P. Complementary and alternative medicine use in infertility: cultural and religious influences in a multicultural Canadian setting. J Altern Complement Med. 2014;20(9):686-692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Smith CA, Armour M, Betts D. Treatment of women’s reproductive health conditions by Australian and New Zealand acupuncturists. Complement Ther Med. 2014;22(4):710-718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Birkeflet O, Laake P, Vøllestad N. Traditional Chinese medicine patterns and recommended acupuncture points in infertile and fertile women. Acupunct Med. 2012;30(1):12-16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Johansson J, Redman L, Veldhuis PP, et al. Acupuncture for ovulation induction in polycystic ovary syndrome: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2013;304(9):E934-E943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jedel E, Labrie F, Odén A, et al. Impact of electro-acupuncture and physical exercise on hyperandrogenism and oligo/amenorrhea in women with polycystic ovary syndrome: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2011;300(1):E37-E45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Park JJ, Kang M, Shin S, et al. Unexplained infertility treated with acupuncture and herbal medicine in Korea. J Altern Complement Med. 2010;16(2):193-198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kuang H, Li Y, Wu X, et al. Acupuncture and clomiphene citrate for live birth in polycystic ovary syndrome: study design of a randomized controlled trial. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2013;2013:527303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chen Z, Zhang Y, Liu J, et al. Diagnosis of polycystic ovary syndrome: standard and guideline of Ministry of Health of People’s Republic of China. Zhonghua Fu Chan Ke Za Zhi. 2012;47(1):74-75.22455684 [Google Scholar]

- 18.Li R, Qiao J, Yang D, et al. Epidemiology of hirsutism among women of reproductive age in the community: a simplified scoring system. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2012;163(2):165-169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhao X, Ni R, Li L, et al. Defining hirsutism in Chinese women: a cross-sectional study. Fertil Steril. 2011;96(3):792-796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhou B; Coorperative Meta-Analysis Group of China Obesity Task Force . Predictive values of body mass index and waist circumference to risk factors of related diseases in Chinese adult population [in Chinese]. Zhonghua Liu Xing Bing Xue Za Zhi. 2002;23(1):5-10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wu XK, Wang YY, Liu JP, et al. ; Reproductive and Developmental Network in Chinese Medicine . Randomized controlled trial of letrozole, berberine, or a combination for infertility in the polycystic ovary syndrome. Fertil Steril. 2016;106(3):757-765, e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Legro RS, Wu X, Barnhart KT, Farquhar C, Fauser BC, Mol B; Harbin Consensus Conference Workshop Group . Improving the Reporting of Clinical Trials of Infertility Treatments (IMPRINT): modifying the CONSORT statement. Hum Reprod. 2014;29(10):2075-2082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Harbin Consensus Conference Workshop Group Improving the Reporting of Clinical Trials of Infertility Treatments (IMPRINT): modifying the CONSORT statement. Fertil Steril. 2014;102(4):952-959, e15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wu X, Wang Y, Liu J, et al. Letrozole, berberine, or a combination for infertility in Chinese women with polycystic ovary syndrome: a multicentre, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2015;386:S70. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)00651-0 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Li Y, Li Y, Yu Ng EH, et al. Polycystic ovary syndrome is associated with negatively variable impacts on domains of health-related quality of life: evidence from a meta-analysis. Fertil Steril. 2011;96(2):452-458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hu M, Richard JE, Maliqueo M, et al. Maternal testosterone exposure increases anxiety-like behavior and impacts the limbic system in the offspring. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2015;112(46):14348-14353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Legro RS, Kunselman AR, Brzyski RG, et al. ; NICHD Reproductive Medicine Network . The Pregnancy in Polycystic Ovary Syndrome II (PPCOS II) trial: rationale and design of a double-blind randomized trial of clomiphene citrate and letrozole for the treatment of infertility in women with polycystic ovary syndrome. Contemp Clin Trials. 2012;33(3):470-481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Streitberger K, Kleinhenz J. Introducing a placebo needle into acupuncture research. Lancet. 1998;352(9125):364-365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.MacPherson H, Hammerschlag R, Coeytaux RR, et al. Unanticipated insights into biomedicine from the study of acupuncture. J Altern Complement Med. 2016;22(2):101-107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kar S, Sanchita S. Clomiphene citrate, metformin or a combination of both as the first line ovulation induction drug for Asian Indian women with polycystic ovarian syndrome: a randomized controlled trial. J Hum Reprod Sci. 2015;8(4):197-201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zain MM, Jamaluddin R, Ibrahim A, Norman RJ. Comparison of clomiphene citrate, metformin, or the combination of both for first-line ovulation induction, achievement of pregnancy, and live birth in Asian women with polycystic ovary syndrome: a randomized controlled trial. Fertil Steril. 2009;91(2):514-521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schlaff WD, Zhang H, Diamond MP, et al. ; Reproductive Medicine Network . Increasing burden of institutional review in multicenter clinical trials of infertility: the Reproductive Medicine Network experience with the Pregnancy in Polycystic Ovary Syndrome (PPCOS) I and II studies. Fertil Steril. 2011;96(1):15-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Legro RS, Myers ER, Barnhart HX, et al. ; Reproductive Medicine Network . The Pregnancy in Polycystic Ovary Syndrome study: baseline characteristics of the randomized cohort including racial effects. Fertil Steril. 2006;86(4):914-933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Trial Protocol

eAppendix. Supplemental Methods

eReferences

eFigure. Acupuncture Point Localization in the Active Acupuncture and Control Acupuncture Groups

eTable 1. Distribution of Number of Patients by Site and Treatment Arm

eTable 2. Acupuncture Points, Stimulation, Localization, Tissue in Which Needles Are Inserted, and Innervation Area in Active Acupuncture, Which Consists of Two Protocols That Are Alternated Every Other Treatment, and Control Acupuncture

eTable 3. Secondary Reproductive and Metabolic Outcome Changes From Baseline to Last Visit Measures

eTable 4. Secondary Quality-of-Life Outcomes Score Changes From Baseline to Last Visit Measures

eTable 5. Exploratory Outcomes With Regard to Fecundity