Key Points

Question

When insurers (and their plans) stop providing coverage for Medicaid enrollees (ie, “exit” Medicaid managed care), are there associated changes in market-level performance in quality of care?

Findings

In this retrospective cohort study of 366 Medicaid managed care plans, 106 plans exited the Medicaid program from 2006 through 2014. Exit was not associated with significant changes in market-level quality or self-reported patient experience.

Meaning

Health plan exit from the US Medicaid program was frequent, but was not associated with a significant change in health care market performance.

Abstract

Importance

State Medicaid programs have increasingly contracted with insurers to provide medical care services for enrollees (Medicaid managed care plans). Insurers that provide these plans can exit Medicaid programs each year, with unclear effects on quality of care and health care experiences.

Objective

To determine the frequency and interstate variation of health plan exit from Medicaid managed care and evaluate the relationship between health plan exit and market-level quality.

Design, Setting, and Participants

Retrospective cohort of all comprehensive Medicaid managed care plans (N = 390) during the interval 2006-2014.

Exposures

Plan exit, defined as the withdrawal of a managed care plan from a state’s Medicaid program.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Eight measures from the Healthcare Effectiveness Data and Information Set were used to construct 3 composite indicators of quality (preventive care, chronic disease care management, and maternity care). Four measures from the Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems were combined into a composite indicator of patient experience, reflecting the proportion of beneficiaries rating experiences as 8 or above on a 0-to-10–point scale. Outcome data were available for 248 plans (68% of plans operating prior to 2014, representing 78% of beneficiaries).

Results

Of the 366 comprehensive Medicaid managed care plans operating prior to 2014, 106 exited Medicaid. These exiting plans enrolled 4 848 310 Medicaid beneficiaries, with a mean of 606 039 beneficiaries affected by plan exits annually. Six states had a mean of greater than 10% of Medicaid managed care recipients enrolled in plans that exited, whereas 10 states experienced no plan exits. Plans that exited from a state’s Medicaid market performed significantly worse prior to exiting than those that remained in terms of preventive care (57.5% vs 60.4%; difference, 2.9% [95% CI, 0.3% to 5.5%]), maternity care (69.7% vs 73.6%; difference, 3.8% [95% CI, 1.7% to 6.0%]), and patient experience (73.5% vs 74.8%; difference, 1.3% [95% CI, 0.6% to 1.9%]). There was no significant difference between exiting and nonexiting plans for the quality of chronic disease care management (76.2% vs 77.1%; difference, 1.0% [95% CI, −2.1% to 4.0%]). There was also no significant change in overall market performance before and after the exit of a plan: 0.7–percentage point improvement in preventive care quality (95% CI, −4.9 to 6.3); 0.2–percentage point improvement in chronic disease care management quality (95% CI, −5.8 to 6.2); 0.7–percentage point decrease in maternity care quality (95% CI, −6.4 to 5.0]); and a 0.6–percentage point improvement in patient experience ratings (95% CI, −3.9 to 5.1). Medicaid beneficiaries enrolled in exiting plans had access to coverage for a higher-quality plan, with 78% of plans in the same county having higher quality for preventive care, 71.1% for chronic disease management, 65.5% for maternity care, and 80.8% for patient experience.

Conclusions and Relevance

Between 2006 and 2014, health plan exit from the US Medicaid program was frequent. Plans that exited generally had lower quality ratings than those that remained, and the exits were not associated with significant overall changes in quality or patient experience in the plans in the Medicaid market.

This study uses Medicaid administrative data to quantify health plan exit from Medicaid managed care between 2006 and 2014 and to evaluate the change in health care quality associated with plan exit.

Introduction

By 2014, 77% of all Medicaid recipients were enrolled in some form of managed care. Under most managed care arrangements, states contract with insurance companies, which in turn assume risk and provide comprehensive medical services for enrollees. Many policy observers have expressed concerns about the potential negative effects of managed care on the quality of care for Medicaid enrollees.

The partnership between state Medicaid agencies and health plans embodies an inherent asymmetry between the 2 entities: states must ensure access to health services for eligible Medicaid recipients, whereas health plans may choose to terminate an insurance product if it is no longer financially viable. The instability of partnerships between states and plans can have significant effects on enrollee quality, continuity of care, competition, and health care experiences. When plans leave a market, enrollees must transition to a new plan with different physician networks and administrative practices, posing challenges for displaced enrollees to access care in a timely fashion. Additionally, the remaining plans in the market are forced to cope with an influx of new enrollees, who often have little experience with their networks and administrative processes. While insurance plan exits may result in short-term disruptions for individuals engaged in care, they may also have long-term benefits for health care markets if lower-performing plans are more likely to exit.

Despite increasing reliance of Medicaid on managed care partnerships, to the best of our knowledge no nationally representative studies have examined the prevalence and consequences of plan exit for Medicaid enrollees. The purpose of this study was to evaluate the frequency and interstate variation of health plan exit from Medicaid managed care and to investigate the relationship between health plan exits and the quality of care delivered in Medicaid managed care markets.

Methods

Overview

This study was deemed exempt from review by the institutional review board at Yale University. We analyzed the annual participation of all plans contracting with state Medicaid agencies and examined whether health plan exit was associated with changes in the quality of health plans available for Medicaid managed care enrollees experiencing transitions.

Sources of Data and Study Population

Data on market participation for all comprehensive (full-benefit) Medicaid managed care organizations were obtained from the Medicaid managed care enrollment reports for 2006 to 2014. The enrollment reports, compiled annually by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS), contain year-specific data on plan geography and characteristics, including the number of Medicaid recipients enrolled in each managed care organization at the mid-year point (June 30). Health plan regulatory filings to the National Association of Insurance Commissioners provided additional detail on organizational strategies (ie, mergers and acquisitions) that might affect market participation.

To estimate the relationship between plan exit and health plan quality, we obtained information on health plan performance from the Healthcare Effectiveness Data and Information Set (HEDIS) and Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems (CAHPS) compiled by the National Committee for Quality Assurance (NCQA) for 2006 to 2014. HEDIS is a quality measurement tool used by more than 90% of health plans nationally and is the basis of performance assessment for health plan accreditation. While the submission of HEDIS data for Medicaid is not mandatory for all states, 79% of Medicaid recipients in comprehensive managed care plans were enrolled in organizations that submitted HEDIS data to the NCQA in 2014. CAHPS surveys are broadly used to elicit patient experiences with health care systems and have served as a tool for benchmarking across health plans. The data submitted from health plans are audited; HEDIS data are reported as the proportion of eligible individuals who received recommended care in a given year, while CAHPS data represent the proportion of beneficiaries rating experiences as 8 or above on a 0-to-10-point scale. Additional details on data collection processes and quality assurance are available elsewhere.

Variables

The primary outcome for this study was the frequency of health plan exits from state Medicaid managed care programs. A plan was categorized as exiting the Medicaid managed care program in a state if it was present in a given year and not included in the enrollment report in the subsequent year. Plan exits were confirmed using regulatory filings and web searches for press releases and other plan-related forms of announcement, and each plan exit was verified using at least 2 sources. In primary analyses, plan exits were counted when a plan left a state’s Medicaid managed care market or was subject to a merger or acquisition, resulting in a transition for enrollees. Because it was not always explicit whether mergers and acquisitions resulted in meaningful transitions for enrollees, a sensitivity analysis was conducted in which the definition of plan exit was limited to cases in which we could find documentation of a plan completely leaving the market. In all analyses, branding-related changes of plan names were not counted as exits.

To estimate the association between health plan exit and the quality of plans available for Medicaid recipients, our analysis relied on 8 measures of health care quality from the HEDIS (combined to construct the 3 composite measures of preventive care, chronic disease care management, and maternity care) and 4 measures of patient experience from the CAHPS (combined to construct a single composite) (eTable 1 in the Supplement). These measures allowed for the evaluation of the continuum of care received by Medicaid beneficiaries and were consistent with measures recommended by CMS to measure quality of care and patient experience in the Medicaid program.

Statistical Analysis

Our primary analysis examined rates of plan exit within and across Medicaid managed care markets as indicated in the CMS enrollment reports. To examine how many beneficiaries were affected by plan exit, we aggregated the number of individuals in exiting plans per year in each state. We then determined the proportion of beneficiaries in exiting plans, as well as the proportion of plans that exited, using a state-specific denominator to account for states that adopted or eliminated comprehensive Medicaid managed care programs during the study period.

Composite measures of quality for each of the 4 domains of care (preventive care, chronic disease care management, maternity care, and patient experience) were constructed by calculating mean z scores across the individual measures, which were then rescaled using the raw mean and standard deviation to aid interpretation. Three separate analyses were used to examine the relationship between plan exit and health care quality.

First, for each of the 4 domains of care, we compared the prior performance of plans that exited a state’s managed care program with plans that did not exit over the study interval using an ordinary least squares regression with state and year fixed effects, weighted by plan size. The unit of analysis was the plan-year, and the inclusion of fixed effects allowed us to identify performance differences between exiting and nonexiting plans within a state and year to ensure plans were compared with other managed care plans operating contemporaneously in the same Medicaid market. In all cases in which plans did not report their total membership for inclusion in the HEDIS and CAHPS data sets, beneficiary counts were obtained from the enrollment reports, which were assessed at a different point in the year but were generally concurrent with the estimates from the HEDIS and CAHPS submissions. We conducted a sensitivity analysis measuring performance using only the 2 years of data prior to a plan exit.

Second, we were interested in understanding the extent to which the exit of a plan and the subsequent transition of enrollees to a new plan was associated with changes in the performance of the remaining plans in the market. To do this, we constructed generalized linear models to examine the association between plan exit and the change in overall performance of plans in affected Medicaid managed care markets in the year following a plan exit. Managed care markets were defined as the counties in which a given plan operated prior to exit. Changes in quality were estimated before and after plan exits for all plans operating in at least 1 county affected by plan exit. Models compared the weighted mean performance across all reporting plans in the year prior to a health plan exiting with the mean performance of all reporting plans in the year following a health plan exit, where the treatment indicator was “0” if a plan was in operation in a managed care market in the year prior to a plan exit from that market and “1” in the year after a plan exited the market. Models assessing the association between plan exit and changes in market quality used state fixed effects, as well as controls for a plan’s state-level market share, profit status, enrollment, and whether the plan only served Medicaid beneficiaries. Statistical models clustered all standard errors at the state level to account for the nonindependence of observations across years and limited analyses to plans that contributed data both before and after a plan exit. We conducted a sensitivity analysis to determine whether the effects of plan exit were different in markets in which the exiting plan had a larger share of a state’s Medicaid managed care market (exiting plans with market share greater than or equal to the state- and year-specific median), hypothesizing that the exit of larger plans would result in the need for remaining plans to accommodate a larger number of enrollees.

The third analysis sought to determine the likelihood that a Medicaid beneficiary in a state would have an opportunity to enroll in a higher-quality plan in the year after his or her original plan exited the county-defined market. Because differences in the performance of nonexiting and exiting plans are based on weighted means, they may be influenced by large plans and outlier performers. Accordingly, this analysis effectively determined the “typical” plan performance in the year following a plan exit, an important statistic for beneficiaries who are autoassigned into new plans after a plan exit.

Analyses were conducted using Stata/SE version 14.1 (StataCorp), and results from all statistical tests are reported with P values derived from 2-tailed tests of statistical significance (at P < .05).

Results

Frequency and Variation in Plan Exit

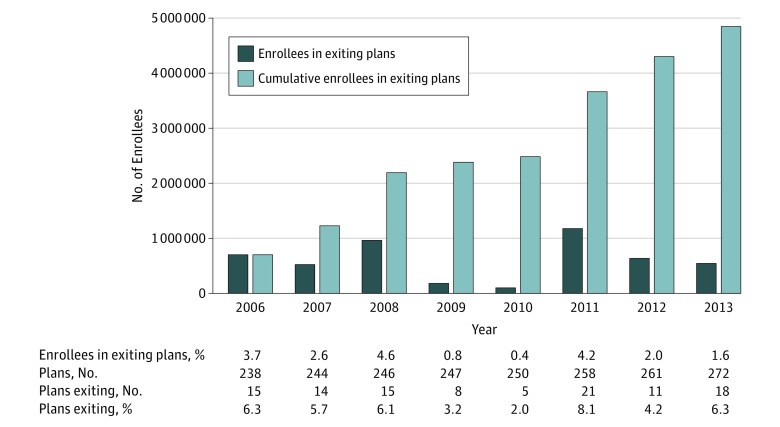

The final sample consisted of 390 comprehensive Medicaid managed care plans contributing 2294 plan-years during the study period 2006 to 2014. Data on quality of care was available for 1499 of the plan-years. Plans that did not report quality data were smaller, had less market share, had operated in Medicaid for fewer years, and were more likely to only serve Medicaid enrollees (eTable 2 in the Supplement). The annual sample increased from 238 comprehensive managed care plans that enrolled 18.9 million enrollees in 2006 to 278 plans and 42.9 million enrollees in 2014 (Figure 1). Plans entering the Medicaid managed care program in 2014 (N = 24) were excluded from all analyses, as there were insufficient data to determine whether they subsequently exited the program. During the study period, 106 managed care plans exited Medicaid, representing 4 848 310 Medicaid managed care enrollees affected by plan exit, a mean of 606 039 enrollees annually. Compared with nonexiting plans, exiting plans were significantly smaller and had fewer years of operation. Other organizational characteristics did not significantly differ between the 2 groups (Table 1).

Figure 1. Trends in Medicaid Managed Care Plan Exit, 2006-2014.

Table 1. Characteristics of Exiting and Nonexiting Plans, 2006-2014.

| Characteristics | Nonexiting Plans | Exiting Plans | Difference (95% CI) | P Valuea |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of plans | 260 | 106 | ||

| Enrollment, median (IQR) | 64 852 (24 835 to 145 418) |

32 019 (7325 to 67 722) |

32 833 (20 057-45 609) |

<.001 |

| Market share, median (IQR) | 7.2 (2.4 to 22.7) | 5.3 (0.9 to 14.6) | 1.9 (0.5-3.3) | .01 |

| Years in business, median (IQR)b | 9 (5 to 9) | 3 (2 to 6) | 6 (6-7) | <.001 |

| Plans in region, No. (%) | ||||

| Northeast | 52 (20.0) | 20 (18.9) | 1.1 (−7.9 to 10.2) | .81 |

| Midwest | 64 (24.6) | 32 (30.2) | −5.5 (−15.6 to 4.4) | .27 |

| South | 73 (28.1) | 34 (32.1) | −4.0 (−14.3 to 6.3) | .45 |

| West | 71 (27.3) | 20 (18.9) | 8.4 (−1.3 to 18.2) | .09 |

| For-profit plans, No. (%) | 138 (53.1) | 57 (53.8) | −0.7 (−12.0 to 10.6) | .90 |

| Medicaid-only plans, No. (%)c | 118 (45.3) | 58 (54.7) | −9.3 (−20.6 to 2.0) | .11 |

Abbreviation: IQR, interquartile range.

Reflects 2-sided Wilcoxon rank sum test for enrollment, market share, and years in business variables; all other P values reflect 2-sided t test.

Indicates median number of years plan present in Medicaid Managed Care Enrollment Reports, 2006-2014.

Indicates whether plan served only Medicaid beneficiaries or both Medicaid and commercial beneficiaries.

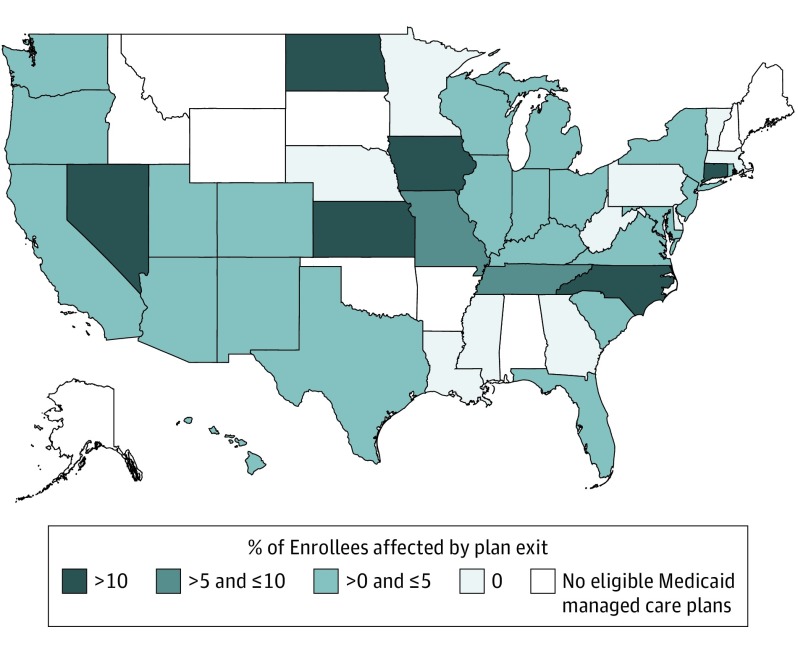

The frequency of plan exit varied considerably from year to year, with the number exiting ranging from 5 plans (2% of those operating annually) serving 102 259 Medicaid recipients in 2010 to 21 plans (8% of those operating annually) serving approximately 1.2 million recipients in 2011, although no consistent time trends were evident. There was significant geographic variation in the rates of health plan exits among states, with 6 states (Connecticut, District of Columbia, Iowa, Kansas, North Carolina, North Dakota, and Nevada) having a mean of more than 10% of their Medicaid managed care recipients annually enrolled in plans that exited. This contrasts with 10 states (Delaware, Georgia, Louisiana, Massachusetts, Minnesota, Mississippi, Nebraska, Pennsylvania, Vermont, and West Virginia) that experienced no plan exit during the 8-year study period (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Proportion of Medicaid Managed Care Enrollees Affected by Plan Exit, 2006-2014.

Map reflects the mean proportion of enrollees in comprehensive managed care plans affected by plan transitions in each state. The median number of enrollees affected by plan transitions was 1795 (interquartile range, 0 to 14 719).

Association Between Plan Exit and Changes in Quality

Plans that left Medicaid managed care markets had lower performance in quality of care and lower ratings in patient experience than plans that remained (Table 2). Plans that exited from a state’s Medicaid market performed significantly worse prior to exit than those that remained in terms of preventive care (57.5% vs 60.4%; difference, 2.9% [95% CI, 0.3% to 5.5%]), maternity care (69.7% vs 73.6%; difference, 3.8% [95% CI 1.7% to 6.0%]), and patient experience (73.5% vs 74.8%; difference, 1.3% [95% CI, 0.6% to 1.9%]). There was no significant difference between exiting and nonexiting plans for the quality of chronic disease care management (76.2% vs 77.1%; difference, 1.0% [95% CI, −2.1% to 4.0%]). There was no significant difference between exiting and nonexiting plans for the quality of chronic disease care management (76.2% vs 77.1%; difference, 1.0% [95% CI, −2.1% to 4.0%). Sensitivity analyses using a more conservative indicator of plan exit and limiting prior plan performance to 2 years of data yielded changes in quality that were similar in magnitude but less precise than the primary results (eTable 3 in the Supplement).

Table 2. Quality of Exiting and Nonexiting Plans, 2006-2014a.

| Composite Quality | Nonexiting Plan Quality | Exiting Plan Quality | Quality Difference | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (95% CI), % | Plan-Years, No. | Mean (95% CI), % | Plan-Years, No. | Mean (95% CI), % | P Value | |

| Preventive care | 60.4 (60.2 to 60.5) | 1187 | 57.5 (55.0 to 59.9) | 180 | 2.9 (0.3 to 5.5) | .03 |

| Chronic disease care management | 77.1 (77.0 to 77.3) | 1226 | 76.2 (73.3 to 79.0) | 183 | 1.0 (−2.1 to 4.0) | .53 |

| Maternity care | 73.6 (73.5 to 73.7) | 957 | 69.7 (67.7 to 71.8) | 147 | 3.8 (1.7 to 6.0) | .001 |

| Patient experience | 74.8 (74.7 to 74.8) | 742 | 73.5 (72.9 to 74.1) | 100 | 1.3 (0.6 to 1.9) | <.001 |

Quality reflects plan-level performance (0%-100%) for composite measures generated from Healthcare Effectiveness Data and Information Set (HEDIS) and Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems (CAHPS) data.

There was no significant association of plan exit with the quality of care delivered in the remaining Medicaid managed care plans operating in markets affected by plan exit (Table 3). In the year following a plan exit, markets experienced changes in the quality of care that were not statistically significant: 0.7–percentage point improvement in preventive care quality (95% CI, −4.9 to 6.3); 0.2–percentage point improvement in chronic disease care management quality (95% CI, −5.8 to 6.2) ; 0.7–percentage point decrease in maternity care quality (95% CI, −6.4 to 5.0) ; and a 0.6–percentage point improvement in patient experience ratings (95% CI, −3.9 to 5.1). Analyses using the more conservative indicator of plan exit or those limited to markets affected by exiting plans with relatively large (greater than or equal to median) market share yielded similar results (eTables 4 and 5 in the Supplement).

Table 3. Change in Mean Market Quality Following Plan Exit, 2006-2014a.

| Pre-Exit Year | Pre-Exit Quality Score | Post-Exit Quality Score | Quality Change | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (95% CI), % | Plan-Years, No. | Mean (95% CI), % | Plan-Years, No. | Change (95% CI), % | P Value | |

| Preventive Care Quality Composite | ||||||

| 2006 | 58.3 (57.3 to 59.2) | 17 | 58.0 (57.1 to 58.9) | 20 | −0.3 (−2.1 to 1.6) | .72 |

| 2007 | 58.4 (57.1 to 59.7) | 23 | 59.8 (58.8 to 60.7) | 27 | 1.4 (−0.9 to 3.6) | .19 |

| 2008 | 58.2 (56.2 to 60.2) | 30 | 59.4 (57.9 to 60.9) | 36 | 1.2 (−2.3 to 4.8) | .44 |

| 2009 | 58.4 (56.6 to 60.2) | 20 | 58.2 (57.0 to 59.4) | 22 | −0.2 (−3.2 to 2.8) | .89 |

| 2010 | 59.5 (58.2 to 60.8) | 22 | 60.5 (59.6 to 61.4) | 26 | 1.0 (−1.3 to 3.2) | .29 |

| 2011 | 59.0 (57.1 to 61.0) | 22 | 60.6 (59.1 to 62.0) | 18 | 1.5 (−1.8 to 4.9) | .27 |

| 2012 | 61.6 (61.0 to 62.2) | 44 | 62.2 (61.6 to 62.8) | 39 | 0.6 (−0.6 to 1.8) | .28 |

| 2013 | 63.5 (62.2 to 64.8) | 42 | 63.6 (62.6 to 64.5) | 38 | 0.1 (−2.2 to 2.3) | .95 |

| Overallb | 60.1 (56.9 to 63.4) | 220 | 60.6 (58.2 to 63.1) | 226 | 0.7 (−4.9 to 6.3) | .52c |

| Chronic Disease Management Quality Composite | ||||||

| 2006 | 74.3 (73.1 to 75.5) | 17 | 77.5 (76.4 to 78.5) | 19 | 3.1 (0.8 to 5.5) | .02 |

| 2007 | 78.8 (77.0 to 80.6) | 23 | 77.9 (76.7 to 79.2) | 27 | −0.8 (−3.9 to 2.3) | .54 |

| 2008 | 76.9 (75.8 to 77.9) | 29 | 79.0 (78.2 to 79.8) | 35 | 2.2 (0.3 to 4.0) | .03 |

| 2009 | 74.4 (72.7 to 76.2) | 21 | 75.7 (74.6 to 76.8) | 22 | 1.3 (−1.6 to 4.1) | .30 |

| 2010 | 77.2 (75.0 to 79.3) | 22 | 74.6 (73.1 to 76.1) | 26 | −2.5 (−6.2 to 1.2) | .13 |

| 2011 | 80.6 (80.2 to 81.1) | 24 | 76.7 (76.3 to 77.0) | 19 | −3.9 (−4.8 to −3.1) | <.001 |

| 2012 | 75.1 (73.7 to 76.5) | 46 | 76.6 (75.2 to 78.0) | 43 | 1.5 (−1.3 to 4.3) | .25 |

| 2013 | 76.7 (74.8 to 78.6) | 42 | 76.2 (74.8 to 77.6) | 38 | −0.5 (−3.8 to 2.8) | .73 |

| Overallb | 76.7 (73.3 to 80.1) | 224 | 76.8 (74.3 to 79.3) | 229 | 0.2 (−5.8 to 6.2) | .91c |

| Maternity Care Quality Composite | ||||||

| 2006 | ||||||

| 2007 | ||||||

| 2008 | ||||||

| 2009 | 69.7 (66.5 to 72.9) | 19 | 69.2 (67.2 to 71.3) | 19 | −0.5 (−5.7 to 4.8) | .82 |

| 2010 | 66.2 (64.7 to 67.7) | 11 | 68.5 (67.3 to 69.7) | 14 | 2.3 (−0.5 to 5.0) | .08 |

| 2011 | 77.2 (76.0 to 78.3) | 22 | 76.6 (75.8 to 77.3) | 25 | −0.6 (−2.5 to 1.3) | .46 |

| 2012 | 73.9 (73.2 to 74.5) | 47 | 73.0 (72.4 to 73.7) | 47 | −0.9 (−2.2 to 0.5) | .17 |

| 2013 | 74.6 (72.4 to 76.9) | 45 | 73.1 (71.4 to 74.8) | 38 | −1.5 (−5.5 to 2.5) | .40 |

| Overallb | 73.5 (70.2 to 76.8) | 144 | 72.7 (70.4 to 75.0) | 143 | −0.7 (−6.4 to 5.0) | .49c |

| Patient Experience Quality Composite | ||||||

| 2006 | 70.2 (68.1 to 72.3) | 12 | 70.1 (67.7 to 72.5) | 11 | −0.1 (−4.7 to 4.4) | .92 |

| 2007 | 71.4 (69.9 to 73.0) | 20 | 72.8 (71.6 to 74.0) | 22 | 1.4 (−1.4 to 4.1) | .26 |

| 2008 | 72.8 (72.0 to 73.5) | 18 | 72.0 (71.4 to 72.7) | 18 | −0.8 (−2.1 to 0.6) | .22 |

| 2009 | 70.7 (68.9 to 72.5) | 12 | 72.6 (70.9 to 74.3) | 11 | 1.9 (−1.6 to 5.4) | .18 |

| 2010 | 72.6 (71.4 to 73.8) | 10 | 73.2 (72.3 to 74.1) | 12 | 0.5 (−1.6 to 2.6) | .51 |

| 2011 | 74.9 (74.5 to 75.3) | 9 | 75.9 (75.7 to 76.2) | 10 | 1.0 (0.4 to 1.7) | .02 |

| 2012 | 75.4 (74.8 to 76.0) | 33 | 76.6 (76.0 to 77.2) | 32 | 1.2 (0.1 to 2.4) | .04 |

| 2013 | 76.3 (75.3 to 77.2) | 30 | 76.1 (75.5 to 76.7) | 32 | −0.1 (−1.7 to 1.4) | .83 |

| Overallb | 73.7 (71.3 to 76.0) | 144 | 74.3 (72.2 to 76.4) | 148 | 0.6 (−3.9 to 5.1) | .47c |

Quality reflects plan-level performance (0%-100%) for composite measures generated from Healthcare Effectiveness Data and Information Set (HEDIS) and Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems (CAHPS) data.

Reflects mean market quality in the year before and after plan exits across all study years, weighted by plan-years.

Reflects application of weighted z score method.

When assessing the plans available for displaced beneficiaries, most Medicaid beneficiaries enrolled in exiting plans could obtain coverage from a higher-quality plan: 78.3% of available plans in the same county were higher quality based on the preventive care composite, 71.6% based on the chronic disease care management composite, 65.5% based on the maternity care composite, and 80.8% of plans based on the patient experience composite.

Discussion

Almost 5 million enrollees were in managed care plans that exited their state Medicaid programs from 2006 through 2014, a consequence of more than 100 plans that no longer operated in their markets. Plans that left markets were lower performing across multiple dimensions of quality than the plans that remained. Moreover, the reallocation of beneficiaries in exiting plans to plans that remained did not appear to induce short-term deficits in market quality. For most individuals experiencing plan exit, the available set of plans remaining in their market were of higher quality than the plans that exited.

This study highlights challenges for states seeking to modernize their Medicaid programs. Given the number of plan exits and affected enrollees this analysis observed, some state regulators will need to remain vigilant to ensure that managed care plans have meaningful competition within markets to achieve the theoretical benefits associated with a widespread transition to managed care. These results also underscore the complexity of balancing incentives for Medicaid recipients and markets in states adopting competitive managed care models. Some health plan exits may promote higher-quality care if plans with lagging performance leave the Medicaid managed care market. Nonetheless, plan exit may also create instability for enrollees who must transition to new insurers.

Despite the growing presence of managed care plans in public insurance programs, there has been little recent research on plan exit from health insurance markets. Previous work has found similarly high rates of plan exit from counties in the early years of the Medicare Advantage (Medicare + Choice) program; low participation in the program, however, resulted in fewer enrollees affected by plan exit. Studies of plan exits from Medicaid and Medicare have also determined that for-profit plans and those with limited market share are more likely to exit insurance markets; however, no studies have linked plan exit to the performance of exiting plans or have examined the relative quality of insurance plans available to enrollees following an exit. Although lower-quality plans were more likely to exit Medicaid and their departures did not erode performance among remaining plans, substantial research demonstrates that plan exits can disrupt care for enrollees and sever established patient-physician relationships.

The interest in Medicaid managed care as a strategy to manage costs and stimulate quality has increased over the past decade and is likely to continue in coming years. Medicaid programs have adopted managed care because it provides more certainty over health care spending (since plans are paid a fixed per-capita payment) and holds the potential to promote competition among plans to improve quality and reduce costs. The findings from this study, however, suggest that some markets are especially volatile with respect to plan exit. Several policies are relevant to states interested in mitigating potential negative effects of plan exit. For example, when health plan exits occur, Medicaid programs must be vigilant about assigning enrollees to plans that minimize disruptions to patient-physician relationships and maximize the availability of physicians in the new plan’s network. Additionally, states should consider making performance data readily available to inform enrollees’ choices of new plans.

The stability of Medicaid managed care markets has gained significant policy relevance in recent months because of proposed changes to the financing of the Medicaid program under the American Health Care Act. The potential use of block grants and per capita caps to lower Medicaid spending could reduce states’ payment rates to managed care plans, thereby making Medicaid a less attractive market. As a result, policy observers have speculated that the implementation of fixed spending limits could increase the prevalence of plan exit.

This study has several limitations. First, the data sources could not entirely distinguish between a transition initiated by an insurance plan, the state Medicaid program, or some combination of the two. Second, quality and patient experience composites only included a subset of the available recommended quality metrics for Medicaid recipients. Nonetheless, the metrics were consistently reported over time and have been identified by the NCQA and CMS as important indicators of preventive care, chronic disease care management, and maternity care for Medicaid enrollees.

Third, this study only examined the association of Medicaid plan exits with short-term (1-year) changes in quality and patient experience. The effects of plans exiting markets may take a longer period to fully manifest. Fourth, this analysis examined the quality of care in health care markets and was not designed to assess the consequences for individuals in the exiting plans.

Fifth, because CAHPS Medicaid surveys are typically administered by individual states, there is no published information on response rates. Previous studies have determined that low-income populations are less likely to respond to CAHPS surveys; thus, respondents may not be entirely representative of the broader population. There is, however, no evidence that nonresponse rates would be significantly different across exiting and nonexiting plans. Similarly, plans with more median years in business were significantly more likely than shorter serving plans to have missing performance data and higher performance scores. These differences, however, are unlikely to differentially bias the primary results,, because they were observed among both exiting and nonexiting plans (eTable 6 in the Supplement). Sixth, for analyses of quality of care, some plans did not submit CAHPS and HEDIS data in a given year, which may limit generalizability of these findings to all plans. However, these excluded plans enrolled only 21% of beneficiaries.

Conclusions

Between 2006 and 2014, health plan exit from the US Medicaid program was frequent. Plans that exited generally had lower quality ratings than those that remained, and the exits were not associated with significant overall changes in quality or patient experience in the plans in the Medicaid market.

eTable 1. Quality Measures Included in Analysis

eTable 2. Characteristics of Plans With and Without Quality Data

eTable 3. Quality of Exiting and Non-exiting Plans, 2006-14 (sensitivity Analysis With Conservative Estimate of Plan Turnover)

eTable 4. Change in Mean Market Quality Following Plan Exit, 2006-14 (Sensitivity Analysis With Conservative Indicator of Plan Exit)

eTable 5. Change in Mean Market Quality Following Plan Exit, 2006-14 (Sensitivity Analysis for Plans with Large Market Share)

eTable 6. Association Between Market Quality and Plan Characteristics, 2006-14

References

- 1.Kaiser Family Foundation (KFF) Medicaid managed care market tracker. KFF website. http://kff.org/data-collection/medicaid-managed-care-market-tracker/. 2016. Accessed September 19, 2016.

- 2.Landon BE, Epstein AM. Quality management practices in Medicaid managed care: a national survey of Medicaid and commercial health plans participating in the Medicaid program. JAMA. 1999;282(18):1769-1775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Landon BE, Schneider EC, Tobias C, Epstein AM. The evolution of quality management in Medicaid managed care. Health Aff (Millwood). 2004;23(4):245-254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bindman AB, Chattopadhyay A, Osmond DH, Huen W, Bacchetti P. The impact of Medicaid managed care on hospitalizations for ambulatory care sensitive conditions. Health Serv Res. 2005;40(1):19-38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Aitken M. Shift from fee-for-service to managed Medicaid: what is the impact on patient care? QuintilesIMS Institute website. http://www.imshealth.com/en/thought-leadership/quintilesims-institute/reports/shift-from-fee-to-managed-medicaid. 2013. Accessed September 19, 2016.

- 6.Garfield R, Licata R, Young K The uninsured at the starting line: findings from the 2013 Kaiser survey of low-income Americans and the ACA. Kaiser Family Foundation website. http://kff.org/uninsured/report/the-uninsured-at-the-starting-line-findings-from-the-2013-kaiser-survey-of-low-income-americans-and-the-aca/. 2014. Accessed September 19, 2016.

- 7.Long SK, Yemane A. Commercial plans in Medicaid managed care: understanding who stays and who leaves. Health Aff (Millwood). 2005;24(4):1084-1094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chernew ME, Wodchis WP, Scanlon DP, McLaughlin CG. Overlap in HMO physician networks. Health Aff (Millwood). 2004;23(2):91-101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Miller RH, Luft HS. HMO plan performance update: an analysis of the literature, 1997-2001. Health Aff (Millwood). 2002;21(4):63-86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) Medicaid managed care enrollment and program characteristics, 2014. Medicaid.gov website. https://www.medicaid.gov/medicaid-chip-program-information/by-topics/data-and-systems/medicaid-managed-care/downloads/2014-medicaid-managed-care-enrollment-report.pdf. 2014. Accessed September 19, 2016.

- 11.Sommers BD. Insurance cancellations in context: stability of coverage in the nongroup market prior to health reform. Health Aff (Millwood). 2014;33(5):887-894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) Medicaid managed care enrollment report. Medicaid.gov website. https://www.medicaid.gov/medicaid/managed-care/enrollment/index.html. 2014. Accessed September 19, 2016.

- 13.National Committee for Quality Assurance (NCQA) NCQA health plan fact sheet. NCQA website. https://www.ncqa.org/Portals/0/Newsroom/2014/NCQA_Gold_Standard_%20Accreditation.pdf. Accessed May 30, 2017.

- 14.Financial SNL. Insurance rate and product filings. SNL Financial website. http://marketintelligence.spglobal.com/client-solutions/users/insurance-professionals. 2016. Accessed September 19, 2016.

- 15.Landon BE, Hicks LS, O’Malley AJ, et al. Improving the management of chronic disease at community health centers. N Engl J Med. 2007;356(9):921-934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) Medicaid and CHIP managed care final rule. Medicaid.gov website. https://www.medicaid.gov/medicaid/managed-care/guidance/final-rule/index.html. 2016. Accessed December 26, 2016.

- 17.Sommers B, Gordon S, Somers S, Ingram C, Epstein A Medicaid on the eve of expansion: a survey of state Medicaid officials about the ACA. Health Affairs Blog. http://healthaffairs.org/blog/2013/12/30/medicaid-on-the-eve-of-expansion-a-survey-of-state-medicaid-officials-about-the-aca. 2013. Accessed December 26, 2016.

- 18.Iglehart JK. Desperately seeking savings: states shift more Medicaid enrollees to managed care. Health Aff (Millwood). 2011;30(9):1627-1629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Keenan C. Federal agency cites concerns over Iowa Medicaid transition. The Gazette. http://www.thegazette.com/subject/news/health/cms-to-hold-sessions-on-medicaid-transition-20151107. 2015. Accessed December 26, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Halpern R. M+C plan county exit decisions 1999-2001: implications for payment policy. Health Care Financ Rev. 2005;26(3):105-123. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Abraham J, Arora A, Gaynor M, Wholey D. Enter at your own risk: HMO participation and enrollment in the Medicare risk market. Econ Inq. 2000;38(3):385-401. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ginde AA, Lowe RA, Wiler JL. Health insurance status change and emergency department use among US adults. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172(8):642-647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Collins SR, Robertson R, Garber T, Doty MM Gaps in health insurance: why so many Americans experience breaks in coverage and how the Affordable Care Act will help. The Commonwealth Fund website. http://www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/issue-briefs/2012/apr/gaps-in-health-insurance. 2012. Accessed December 26, 2016. [PubMed]

- 24.S&P: states may lose Medicaid managed care plans under AHCA’s per-capita caps. Inside Health Policy website. https://insidehealthpolicy.com/daily-news/sp-states-may-lose-medicaid-managed-care-plans-under-ahca%E2%80%99s-capita-caps. March 21, 2017. Accessed April 11, 2017.

- 25.Boscardin CK, Gonzales R. The impact of demographic characteristics on nonresponse in an ambulatory patient satisfaction survey. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2013;39(3):123-128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) Fielding the CAHPS® Health Plan Survey 4.0: Medicaid version. AHRQ website. https://www.cahpsdatabase.ahrq.gov/files/HPGuidance/Fielding_the_CAHPS%20Health%20Plan%20Survey%20Medicaid%20Version.pdf. 2008. Accessed May 20, 2017.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eTable 1. Quality Measures Included in Analysis

eTable 2. Characteristics of Plans With and Without Quality Data

eTable 3. Quality of Exiting and Non-exiting Plans, 2006-14 (sensitivity Analysis With Conservative Estimate of Plan Turnover)

eTable 4. Change in Mean Market Quality Following Plan Exit, 2006-14 (Sensitivity Analysis With Conservative Indicator of Plan Exit)

eTable 5. Change in Mean Market Quality Following Plan Exit, 2006-14 (Sensitivity Analysis for Plans with Large Market Share)

eTable 6. Association Between Market Quality and Plan Characteristics, 2006-14