Abstract

Importance

Surgical procedures for the aging face—including face-lift, blepharoplasty, and brow-lift—consistently rank among the most popular cosmetic services sought by patients. Although these surgical procedures are broadly classified as procedures that restore a youthful appearance, they may improve societal perceptions of attractiveness, success, and health, conferring an even larger social benefit than just restoring a youthful appearance to the face.

Objectives

To determine if face-lift and upper facial rejuvenation surgery improve observer ratings of age, attractiveness, success, and health and to quantify the effect of facial rejuvenation surgery on each individual domain.

Design, Setting, and Participants

A randomized clinical experiment was performed from August 30 to September 18, 2016, using web-based surveys featuring photographs of patients before and after facial rejuvenation surgery. Observers were randomly shown independent images of the 12 patients; within a given survey, observers saw either the preoperative or postoperative photograph of each patient to reduce the possibility of priming. Observers evaluated patient age using a slider bar ranging from 30 to 80 years that could be moved up or down in 1-year increments, and they ranked perceived attractiveness, success, and health using a 100-point visual analog scale. The bar on the 100-point scale began at 50; moving the bar to the right corresponded to a more positive rating in these measures and moving the bar to the left, a more negative rating.

Main Outcomes and Measures

A multivariate mixed-effects regression model was used to understand the effect of face-lift and upper facial rejuvenation surgery on observer perceptions while accounting for individual biases of the participants. Ordinal rank change was calculated to understand the clinical effect size of changes across the various domains after surgery.

Results

A total of 504 participants (333 women, 165 men, and 6 unspecified; mean age, 29 [range, 18-70] years) successfully completed the survey. A multivariate mixed-effects regression model revealed a statistically significant change in age (–4.61 years; 95% CI, –4.97 to –4.25) and attractiveness (6.72; 95% CI, 5.96-7.47) following facial rejuvenation surgery. Observer-perceived success (3.85; 95% CI, 3.12-4.57) and health (7.65; 95% CI; 6.87-8.42) also increased significantly as a result of facial rejuvenation surgery.

Conclusions and Relevance

The data presented in this study demonstrate that patients are perceived as younger and more attractive by the casual observer after undergoing face-lift and upper facial rejuvenation surgery. These procedures also improved ratings of perceived success and health in our patient population. These findings suggest that facial rejuvenation surgery conveys an even larger societal benefit than merely restoring a youthful appearance to the face.

Level of Evidence

NA.

This survey study examines whether face-lift and upper facial rejuvenation surgery improve observer ratings of age, attractiveness, success, and health.

Key Points

Question

Does face-lift and upper facial rejuvenation surgery improve casual observer ratings of age, attractiveness, success, and health in female patients undergoing these popular cosmetic procedures?

Findings

This survey study of 504 participants showed that women who underwent face-lift and upper facial rejuvenation surgery were rated as appearing significantly more youthful, attractive, successful, and healthy as compared with their preoperative counterparts.

Meaning

This study represents a pilot effort that will contribute to an evidence-based body of literature demonstrating the broader societal implications of undergoing face-lift and upper facial rejuvenation surgical procedures.

Introduction

The field of cosmetic surgery continues to grow, as evidenced by the increasing number of services sought by both men and women each year. In 2015, more than 15 million cosmetic procedures were performed, with a total cost of more than $13.5 billion dollars. Surgical procedures for the aging face—including face-lift, blepharoplasty, and brow-lift—consistently rank among the most popular cosmetic procedures.

Although these surgical procedures are broadly classified as those that restore a youthful appearance to the face, many surgeons and patients believe there is more benefit to be derived than simply improving perceptions of age. Studies have cited many patient motivations for undergoing cosmetic procedures that range from increasing attractiveness to self-esteem, which may lead to improvements in both professional and personal relationships. However, there is a paucity of research dedicated to understanding how surgery for the aging face actually changes ratings in many of these domains.

The effect of facial rejuvenation on attractiveness is of particular interest because attractiveness has been shown to influence success. The literature has demonstrated that attractive individuals experience more success than those deemed less attractive. This finding has shown true in arenas extending from industry hiring practices to the judicial system, increasing the importance of understanding attractiveness ratings. Furthermore, perceived health has been shown to be associated with ratings of attractiveness. Insight into how surgery for the aging face alters perceptions of health will provide an additional way in which we can begin to understand the true benefit of facial rejuvenation surgery as perceived by society. Furthermore, it has been our experience that patients presenting for facial rejuvenation surgery wish to improve their appearance in each of these domains, although the domains vary by patient, with some prioritizing success and others prioritizing health and attractiveness, for example.

Presently, evaluating the outcome of a cosmetic procedure relies heavily on patient satisfaction. What may be considered a technically sound result may not be considered an exemplary outcome if the patient is dissatisfied. This situation has prompted the development of tools to measure patient satisfaction before and after surgery. Because patient perspective is paramount in the field of cosmetic surgery, operative success is largely predicated on providing patients with data-driven counsel regarding their expected results after surgery.

To understand outcomes more objectively, several studies have aimed to elucidate how a variety of surgical procedures for the aging face change observer perceptions of age and attractiveness. Studies have shown that these procedures yield a more youthful appearance compared with preoperative ratings. Although a study from 2013 showed no significant increase in attractiveness after surgery for the aging face, a study performed by Reilly et al showed that facial rejuvenation surgery increased ratings of attractiveness, femininity, social skills, and likeability.

Although all these studies contribute meaningfully to the body of work aimed at understanding the effect of surgery for the aging face, the present study attempts to understand surgical outcomes on a more granular level by quantifying the effect size across the various domains. Our primary goal was to determine whether face-lift and upper facial rejuvenation surgery improves observer gradings of age, attractiveness, success, and health. In addition, we sought to quantify the clinical significance of the changes in each of these domains, which will equip physicians to better guide preoperative conversations regarding outcomes after surgery.

Methods

Participants

A total of 815 individuals participated in the study from August 30, 2016, to September 18, 2016. Only those who completed the survey in its entirety were included in the analysis. Individuals were also necessarily excluded from the study if they were younger than 18 years of age or had psychiatric conditions such as schizophrenia or an autism spectrum disorder owing to differences in how these individuals direct attention toward a face as well as how they convey and infer emotional states from a face. With the use of these criteria, 504 of the 815 participants were eligible for inclusion in our analysis. The Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine Institutional Review Board approved this study. All patients whose photographs were featured in the survey provided written informed consent for participation. Survey participants were informed on the survey homepage that continuing on would serve as informed consent to participate.

Instrument

Surveys were built using Qualtrics survey software (Qualtrics). A link was disseminated via various public-access websites. The first page of the survey described the task and relevant exclusion criteria. Participants were instructed that they would be looking at images of faces, some of whom had undergone a face-lift and upper facial rejuvenation surgery and some who had not undergone surgery. Observers were also informed that they would be eligible to enter a drawing for a $20 Amazon gift card on successful completion of the survey by entering their email address.

Images of 12 white female patients (mean [SD] age, 60.5 [4.2] years) who had undergone both face-lift and upper facial rejuvenation surgical procedures were randomly selected from a database containing photographs of patients who have been seen within the Division of Facial Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery at Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine and the Facial Plastic Surgicenter, Baltimore, Maryland. Patients included in the survey had both preoperative and postoperative photographs. Postoperative photographs were captured a mean of 7 months after surgery. Six of the patients had undergone both a face-lift and a blepharoplasty procedure, and 6 of the patients had undergone face-lift, blepharoplasty, and brow-lift procedures. Observers were randomly shown either the preoperative or the postoperative photographs of each patient but saw no more than 1 photograph of each patient in a given survey to reduce the possibility of bias due to priming. An example of image presentation is in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Example of Patient Photographs.

A, Before face-lift and upper facial rejuvenation surgery. B. After face-lift and upper facial rejuvenation surgery. Only the preoperative or postoperative photograph was included in any given survey to reduce the possibility of priming.

For each photograph, observers were asked to estimate the age of the face. To do this, participants were provided a slider bar ranging from 30 to 80 years that could be moved up or down in 1-year increments. They were also asked to rate the perceived attractiveness, successfulness, and health of the individual in the image. For these measures, observers were provided with a 100-point visual analog scale. The bar began at 50, and moving the bar to the right corresponded to a more positive rating in these measures, while moving the bar to the left corresponded to a more negative rating.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using STATA SE, version 13 (Stata Corp). Observer demographics were examined and ratings across the various domains were tabulated. To evaluate the relative accuracy of our observer ratings, we compared the true ages of our patients with the observers’ estimations of preoperative age by using planned hypothesis testing accounting for unequal variance. To evaluate the relative accuracy of our observer ratings, we compared the true ages of our patients with the observers’ estimations of preoperative age by using a 2-sided t test accounting for unequal variance. P < .05 was considered significant.

A multivariate mixed-effects regression model was used to measure the effect size of face-lift and upper facial rejuvenation surgery on each of the domains of interest. This type of model was of particular value as it allowed us to parse out the differences in domain ratings due to surgical effect while accounting for the individual biases of each observer.

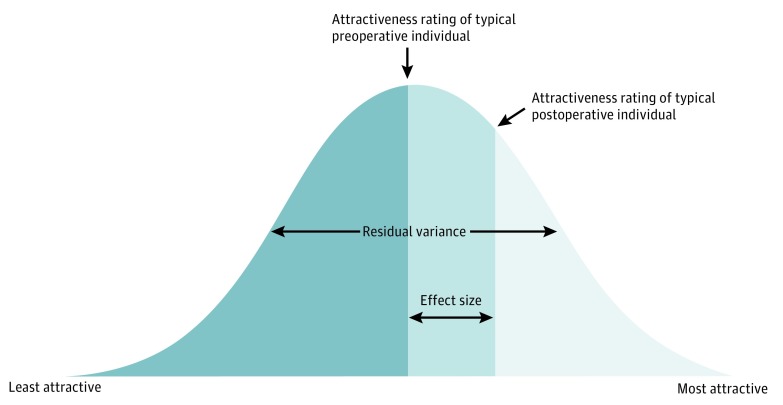

Finally, we aimed to quantify the clinical effect size of the surgical outcomes using an ordinal rank change approach. The multivariate mixed-effects regression model provided a variance component analysis, separating the variance due to observer bias from the regression residual. The residual variances gave us estimates of domain variances that, although they remain confounded by regression error, are independent of observer bias. These estimates were used to generate Gaussian distributions of rankings for all domains, which were then integrated and scaled in Mathematica, version 10.4 (Wolfram Research, Inc). The area under the curve represents the proportion of the population contained within the region of interest, and the difference in the area under the curve between the mean preoperative and mean postoperative values thus gives an estimated ordinal rank change for each domain. Figure 2 shows this measure pictorially using the attractiveness domain as an example.

Figure 2. Pictorial Depiction of Ordinal Rank Change Calculation Using Attractiveness as an Example Domain.

The difference in area under the curve between the preoperative and postoperative groups (medium blue shading) represents the percentage shift in attractiveness after surgery. When applied to a group of 100 rank-ordered individuals, this value will be the number of people a typical individual will shift following face-lift and upper facial rejuvenation surgery in a given domain. The darkest blue shading represents 50% of the population based on preoperative attractiveness ratings.

Results

A total of 504 participants successfully completed the survey and were eligible for inclusion. The mean age of survey participants was 29 (range, 18-70) years. Most of the observers were white (349 [69.2%]), female (333 [66.1%]), and had a 4-year college degree (197 [39.1%]) (Table 1). Results of a t test revealed that there was no significant difference (t1.61, –1.94; 95% CI, –0.70 to 4.58; P = .13) between the true mean (SD) age of our patients (60.5 [4.2] years) and the estimate of the mean (SD) preoperative age (58.6 [7.8] years) provided by the observers.

Table 1. Demographic Characteristics of the 504 Study Participants.

| Observer Characteristic | Value (N = 504)a |

|---|---|

| Age, mean (range), y | 29 (18-70) |

| Sex | |

| Male | 165 (32.7) |

| Female | 333 (66.1) |

| Prefer not to specify | 6 (1.2) |

| Race/ethnicity | |

| Asian | 75 (14.9) |

| African American | 28 (5.6) |

| Hispanic | 29 (5.8) |

| White | 349 (69.2) |

| Other or prefer not to specify | 23 (4.6) |

| Educational level | |

| Less than high school | 2 (0.4) |

| High school or GED | 42 (8.3) |

| Some college | 120 (23.8) |

| 2-y College degree | 27 (5.4) |

| 4-y College degree | 197 (39.1) |

| Master’s degree | 94 (18.7) |

| Doctoral degree | 22 (4.4) |

| Annual household income, US $ | |

| <25 000 | 92 (18.3) |

| 25 000-50 000 | 112 (22.2) |

| >50 000-75 000 | 77 (15.3) |

| >75 000-100 000 | 69 (13.7) |

| >100 000-150 000 | 74 (14.7) |

| >150 000-200 000 | 29 (5.8) |

| >200 000 | 51 (10.1) |

| Procedures for the aging face | |

| Personal history of procedure for the aging face | 31 (6.2) |

| History of friends or relatives having undergone procedures for the aging face | 185 (36.7) |

Abbreviation: GED, General Educational Development certificate.

Data are presented as number (percentage) of patients unless otherwise indicated.

Because the literature has shown an interplay between youth, attractiveness, success, and health, we used a multivariate mixed-effects regression model to understand the association between the various domains as perceived by society (Table 2). In addition to understanding the association between these domains, this model allowed us to account for bias between the observers. The results of the model revealed that patients were rated as appearing significantly younger (coefficient, –4.61 years; 95% CI, –4.97 to –4.25) and more attractive (coefficient, 6.72; 95% CI, 5.96-7.47) after surgery. It also demonstrated that face-lift and upper facial rejuvenation surgery had a positive and statistically significant effect on perceived success (coefficient, 3.85; 95% CI, 3.12-4.57) and perceived health (coefficient, 7.65; 95% CI, 6.87-8.42).

Table 2. Mixed-Effects Multivariate Regression Model.

| Variable and Covariate | Coefficient or Estimatea | SE (95% CI) | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fixed Effects | |||

| Estimated ageb | |||

| Surgery | −4.61 | 0.18 (−4.97 to −4.25) | <.001 |

| Constant | 58.64 | 0.22 (58.21 to 59.07) | <.001 |

| Attractivenessc | |||

| Surgery | 6.72 | 0.38 (5.96 to 7.47) | <.001 |

| Constant | 45.29 | 0.57 (44.17 to 46.42) | <.001 |

| Successfulnessc | |||

| Surgeryc | 3.85 | 0.37 (3.12 to 4.57) | <.001 |

| Constant | 58.14 | 0.42 (57.31 to 58.97) | <.001 |

| Healthc | |||

| Surgery | 7.65 | 0.40 (6.87 to 8.42) | <.001 |

| Constant | 55.62 | 0.46 (54.73 to 56.52) | <.001 |

| Random Effects | |||

| Variance, aged | |||

| Observer | 15.72 | 1.25 (13.46 to 18.36) | |

| Residual | 47.56 | 0.91 (45.82 to 49.36) | |

| Variance, attractivenessd | |||

| Observer | 129.82 | 9.26 (112.87 to 149.32) | |

| Residual | 210.21 | 4.10 (202.33 to 218.39) | |

| Variance, successd | |||

| Observer | 56.48 | 4.66 (48.04 to 66.40) | |

| Residual | 194.55 | 3.84 (187.16 to 202.23) | |

| Variance, healthd | |||

| Observer | 67.26 | 5.50 (57.30 to 78.94) | |

| Residual | 222.61 | 4.40 (214.15 to 231.40) | |

| Covariance, residual | |||

| Age, attractiveness | −15.79 | 1.37 (−18.48 to −13.11) | <.001 |

| Age, success | 0.92 | 1.31 (−1.64 to 3.48) | .48 |

| Age, health | −8.67 | 1.40 (−11.42 to −5.92) | <.001 |

| Attractiveness, success | 100.01 | 3.15 (93.82 to 106.19) | <.001 |

| Attractiveness, health | 117.58 | 3.44 (110.84 to 124.33) | <.001 |

| Health, success | 129.09 | 3.45 (122.31 to 135.86) | <.001 |

Coefficients are given for fixed effects; estimates for random effects.

Observer-estimated age coded on a visual analog scale from 30 to 80 years with 1-year increments.

Observer-perceived attractiveness, success, and health coded on a visual analog scale from 0 to 100 with 1-unit increments.

The variance components are estimates of the spread of the data based on the modeling. The standard reporting of the mixed-effects model does not report a P value for variance as these estimates are not hypothesis tested.

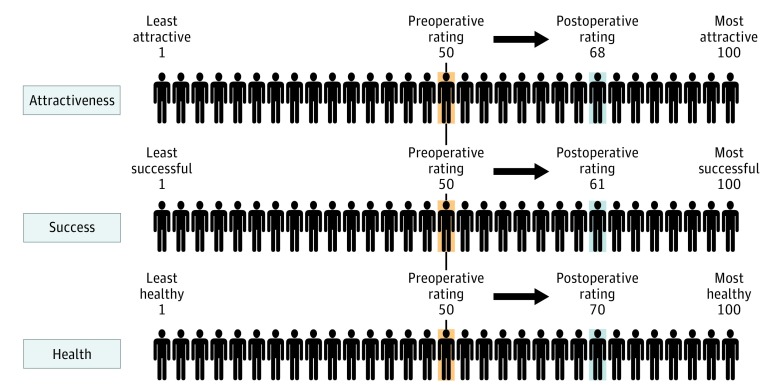

Ordinal rank change is a measure of the clinical effect size of surgery on the domains of interest. Ordinal rank is obtained by randomly sampling a group of 100 individuals and ranking them in the domain of interest, with 1 being the lowest rank and 100 the highest rank. The ordinal rank change provides a measure of how much an average individual will improve in the domain’s ranking after facial rejuvenation surgery. Our data show that if 100 people were randomly sampled and ranked from least attractive to most attractive, the individual ranked 50th (average) would be expected to shift to position 68 in attractiveness following surgery, with this higher value representing a more positive ranking. For the domain of success, an individual ranked 50th would be expected to shift to position 61; for the domain of health, an individual ranked 50th would be expected to shift to position 70. Ordinal rank change in the domains of attractiveness, success, and health are displayed pictorially in Figure 3.

Figure 3. Ordinal Rank Changes Demonstrating Improvement in Domain Rankings Following Face-lift and Upper Facial Rejuvenation Surgery.

The figure surrounded by orange shading represents the average preoperative rating.

We believe that understanding the ordinal rank change can provide a conceptual framework for physicians and patients when offering preoperative counsel. Whereas changes in age can be more intuitively quantifiable, there is no standardized metric by which we measure changes in perceived attractiveness, success, and health. Therefore, ordinal rank can help to better illustrate the effect of surgery from society’s perspective. We have found that patients, in particular, appreciate this explanation of the benefits. It gives them a tangible understanding of what to expect after surgery and helps them decide whether the changes are worth proceeding with the surgery.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this study represents the largest of its kind to measure the effect of surgery for the aging face on observer perceptions at a granular level by quantifying the effect size of surgery on each domain. Study participants provided insight into the broader societal implications of undergoing surgery for the aging face by not only ranking age but also rating perceived attractiveness, success, and health.

Our study, much like previous work on societal perceptions of cosmetic procedures, relies on the vox populi principle. In brief, Sir Francis Galton demonstrated that, when sampling a crowd, the mean judgment of a large group represents a value that each of the group’s individual members may not have been able to discern independently. This principle continues to be applied broadly across many disciplines. For our purposes, applying this theory allows us to conclude that, despite bias on the part of individual observers, the mean value the group assigned to each domain rating should closely approximate the true value attributed to each face by society.

We believe the data presented in this study are a meaningful contribution to the existing body of literature regarding procedures for the aging face. Although changes in perceived age and attractiveness have been measured previously, our study is unique in its exploration of how face-lift and upper facial rejuvenation surgery alter perceived health and success. In addition, the use of multivariate mixed-effects modeling positioned us well to understand the true effect of these procedures by exploring the interplay between all the domains while also accounting for bias between our study observers.

The association between attractiveness and success has been studied in a range of settings, including hiring practices, the judicial system, and political elections. Broadly, individuals ranked as more physically attractive received preferential treatment in many instances, while the less attractive individuals experienced social penalty. Our findings support this notion and indicate that changes in attractiveness ratings after surgery may contribute to increased social and occupational success.

Perceived health has also been shown to be associated with facial attractiveness. Studies have demonstrated that healthy-appearing faces increase observer perceptions of attractive traits and that attractiveness may serve as a phenotypic marker of good health. The link between attractiveness and health has been explored in evolutionary psychology, and it has been argued that facial attractiveness provides an indication of health that can be valuable in mate selection. Although further study will prove necessary, our study supports the association between perceived health and attractiveness, with increases in both domains observed following surgery.

A natural extension of these findings is a series of head-to-head studies regarding how the clinical effect sizes of various procedures for the aging face compare with one another. As we work toward better understanding the effect sizes of each procedure, we can briefly comment here on a preliminary finding. The multivariate mixed-effects regression model is one that has been used previously to study how face-lift surgery alters societal perceptions. It was discovered that adding upper facial rejuvenation to the face-lift procedure yields a larger clinical effect size in the age domain (patients appeared more youthful when undergoing face-lift and upper facial procedures as compared with face-lift alone). These results are relevant even in the setting of an essential difference in the study designs; the face-lift study was conducted using only photographs of the best surgical results, whereas the present study contains photographs with a range of postoperative outcomes.

We looked to prior literature to help explain these preliminary findings. Several studies suggest that the eyes are a key facial attribute used in observer determination of age. Features ranging from eye opening to dark circles around the eyes have been shown to influence observer gradings in this domain. Furthermore, the literature has shown that the use of the eyes to determine perceived age occurs in a range of observer ages, increasing our confidence that the additional change in perceived age in our patients is associated, at least in part, with their upper facial rejuvenation surgery.

Limitations

As a pilot effort, we recognize the limitations of the study design. Our survey distribution relied heavily on social media and public-access websites. This choice may have driven down the mean age of our observers and biased our observer pool more toward white female observers with a college education. We acknowledge that the participant population does not neatly mirror the general population, and more work will be required to fully understand the effects of sex, race/ethnicity, and educational status on societal perceptions of the face.

Despite these findings, the vox populi principle suggests that, with a sufficient number of observers, the mean value measured should closely approximate how society perceives ratings in the various domains so long as each participant provided an individual grading. To this point, when we compared the participants’ preoperative age estimates with the true age of our patient population, we found that there was no statistically significant difference between the observers’ estimation of the mean age and the true mean age of our patient cohort, highlighting the ability of the group to attribute a reasonable estimate to a given domain.

The images featured in the survey were also selected randomly from an existing database of photographs. This random selection of images could not ensure complete standardization across the image pool. It can be difficult to control for factors such as lighting and background in the photographs as well as patient factors such as changes in makeup and hair color, and we recognize these potential confounders in our study. In addition, although the photographs were reviewed for consent and image quality, they were not screened to ensure that all the patients featured had optimal surgical outcomes. Therefore, we believe that the effect sizes reported here will gravitate closer to the mean effect of surgery for the aging face. Although this study design has its merits because it is more generalizable to the typical surgical candidate, we realize that a greater overall effect size in each domain may have been measured using only examples of excellent surgical outcomes. As noted above, this makes the present results difficult to compare with studies in which photographs of only the best surgical outcomes were presented to observers.

Considering that patient candidacy and surgeon skill are important variables that undoubtedly contribute to the ultimate surgical outcome, our small study of only 12 sets of patient images did not afford us the opportunity to study different subsets of surgical outcomes and patient candidates. In future studies, we plan to increase our patient photograph pool by expanding to multiple institutions and to then stratify the images by patient candidacy and surgical outcome. Taking this next step will provide a rich understanding of expected outcomes for all types of surgical patients, which can serve as a guide in patient education and management of expectations.

Conclusions

The data presented in this study demonstrate that patients are perceived as younger and more attractive by the casual observer after undergoing face-lift and upper facial rejuvenation surgery. These procedures also improved ratings of perceived success and health in our patient population. Ultimately, these findings suggest that procedures for the aging face confer a larger societal benefit than simply restoring a more youthful appearance.

References

- 1.American Society of Plastic Surgeons 2015 Plastic Surgery Statistics Report. https://d2wirczt3b6wjm.cloudfront.net/News/Statistics/2015/plastic-surgery-statistics-full-report-2015.pdf. Accessed October 17, 2016.

- 2.American Society for Aesthetic Plastic Surgery 2015 Cosmetic Surgery National Data Bank Statistics. http://www.surgery.org/sites/default/files/ASAPS-Stats2015.pdf. Accessed October 17, 2016. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.von Soest T, Kvalem IL, Skolleborg KC, Roald HE. Psychosocial factors predicting the motivation to undergo cosmetic surgery. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2006;117(1):51-62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Haas CF, Champion A, Secor D. Motivating factors for seeking cosmetic surgery: a synthesis of the literature. Plast Surg Nurs. 2008;28(4):177-182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brown A, Furnham A, Glanville L, Swami V. Factors that affect the likelihood of undergoing cosmetic surgery. Aesthet Surg J. 2007;27(5):501-508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Furnham A, Levitas J. Factors that motivate people to undergo cosmetic surgery. Can J Plast Surg. 2012;20(4):e47-e50. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Little AC, Roberts CS. Evolution, appearance, and occupational success. Evol Psychol. 2012;10(5):782-801. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dion K, Berscheid E, Walster E. What is beautiful is good. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1972;24(3):285-290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Watkins LM, Johnston L. Screening job applicants: the impact of physical attractiveness and application quality. Int J Selection Assessment. 2000;8(2):76-84. doi: 10.1111/1468-2389.00135 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Efran MG. The effect of physical appearance on the judgment of guilt, interpersonal attraction, and severity of recommended punishment in a simulated jury task. J Res Pers. 1974;8(1):45-54. doi: 10.1016/0092-6566(74)90044-0 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sigall H, Ostrove N. Beautiful but dangerous: effects of offender attractiveness and nature of the crime on juridic judgment. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1975;31(3):410-414. doi: 10.1037/h0076472 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rhodes G, Yoshikawa S, Palermo R, et al. Perceived health contributes to the attractiveness of facial symmetry, averageness, and sexual dimorphism. Perception. 2007;36(8):1244-1252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nedelec JL, Beaver KM. Physical attractiveness as a phenotypic marker of health: an assessment using a nationally representative sample of American adults. Evol Hum Behav. 2014;35(6):456-463. doi: 10.1016/j.evolhumbehav.2014.06.004 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ching S, Thoma A, McCabe RE, Antony MM. Measuring outcomes in aesthetic surgery: a comprehensive review of the literature. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2003;111(1):469-480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Klassen AF, Cano SJ, Pusic AL. FACE-Q satisfaction with appearance scores from close to 1000 facial aesthetic patients. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2016;137(3):651e-652e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Klassen AF, Cano SJ, Scott A, Snell L, Pusic AL. Measuring patient-reported outcomes in facial aesthetic patients: development of the FACE-Q. Facial Plast Surg. 2010;26(4):303-309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chauhan N, Warner JP, Adamson PA. Perceived age change after aesthetic facial surgical procedures quantifying outcomes of aging face surgery. Arch Facial Plast Surg. 2012;14(4):258-262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Swanson E. Objective assessment of change in apparent age after facial rejuvenation surgery. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2011;64(9):1124-1131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zimm AJ, Modabber M, Fernandes V, Karimi K, Adamson PA. Objective assessment of perceived age reversal and improvement in attractiveness after aging face surgery. JAMA Facial Plast Surg. 2013;15(6):405-410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Reilly MJ, Tomsic JA, Fernandez SJ, Davison SP. Effect of facial rejuvenation surgery on perceived attractiveness, femininity, and personality. JAMA Facial Plast Surg. 2015;17(3):202-207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Manor BR, Gordon E, Williams LM, et al. Eye movements reflect impaired face processing in patients with schizophrenia. Biol Psychiatry. 1999;46(7):963-969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nakano T, Tanaka K, Endo Y, et al. Atypical gaze patterns in children and adults with autism spectrum disorders dissociated from developmental changes in gaze behaviour. Proc Biol Sci. 2010;277(1696):2935-2943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shackelford TK, Larsen RJ. Facial attractiveness and physical health. Evol Hum Behav. 1999;20(1):71-76. doi: 10.1016/S1090-5138(98)00036-1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mathes EW, Brennan SM, Haugen PM, Rice HB. Ratings of physical attractiveness as a function of age. J Soc Psychol. 1985;125(2):157-168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tatarunaite E, Playle R, Hood K, Shaw W, Richmond S. Facial attractiveness: a longitudinal study. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2005;127(6):676-682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bater KL, Ishii M, Joseph A, Su P, Nellis J, Ishii LE. Perception of hair transplant for androgenetic alopecia. JAMA Facial Plast Surg. 2016;18(6):413-418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Galton F. Vox populi. Nature. 1907;75:450-451. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Surowiecki J. The Wisdom of Crowds: Why the Many Are Smarter Than the Few and How Collective Wisdom Shapes Business, Economies, Societies, and Nations. New York, NY: Doubleday; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Surowiecki J. Mass intelligence [published online May 24, 2004]. Forbes. http://www.forbes.com/global/2004/0524/019.html. Accessed March 13, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Efrain MG, Patterson EWJ. Voters vote beautiful: the effect of physical appearance on a national election. Can J Behav Sci. 1974;6(4):352-356. doi: 10.1037/h0081881 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nellis JC, Ishii M, Papel ID, et al. Association of face-lift surgery with social perception, age, attractiveness, health, and success [published online March 16, 2017]. JAMA Facial Plast Surg. 2017. doi: 10.1001/jamafacial.2016.2206 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nkengne A, Bertin C, Stamatas GN, et al. Influence of facial skin attributes on the perceived age of Caucasian women. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2008;22(8):982-991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Porcheron A, Latreille J, Jdid R, Tschachler E, Morizot F. Influence of skin ageing features on Chinese women’s perception of facial age and attractiveness. Int J Cosmet Sci. 2014;36(4):312-320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]