Abstract

Importance

Recognizing the perceptual threshold for artificial-appearing lips is important to avoid an undesirable outcome of treatment.

Objective

To characterize the quantitative measurements for the perceptual threshold of artificial- and unnatural-appearing lips.

Design, Setting, and Participants

Photographs of a female model’s lips were digitally altered incrementally in 5 sets of features (the upper lip, lower lip, upper and lower lips, and shape of the Cupid’s bow). From December 1, 2013, to January 30, 2014, participants viewed the photographs in random sequence using an online survey and responded to 2 questionnaires after each photograph. The participants were prompted to respond whether each altered photograph of the lips appeared to have received any cosmetic treatment, and whether the lips looked attractive and natural or artificial and unnatural. The measurement of each lip at which 50% of the observers perceived the lips as being treated and 50% of the observers perceived the lips as being artificial was determined. The difference in these 2 measurements was defined as dTA50, which represents the threshold differential between the perception of treated lips and artificial lips for 50% of the observers.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Survey responses of the participants to the appearance of the lips in the photographs.

Results

A total of 98 participants (76 females and 22 males; mean age, 42 years) provided usable responses to the survey. Each area of the lips had a unique quantitative measurement at which the observers perceived the lips as being treated and artificial. Enhancement of the upper lip alone had a narrower margin for artificial appearance (dTA50, 0.9 mm) compared with enhancement of both the upper and lower lips (dTA50, 1.5 mm). Any alteration to the Cupid’s bow resulted in the narrowest margin for artificial appearance (dTA50, 0.3 mm). The difference in the perceptual threshold between the age of the observers was the most significant for the upper lip.

Conclusions and Relevance

The perceptual threshold for treated and/or artificial appearance is unique for each area of the lips.

Level of Evidence

NA.

This survey study characterizes the quantitative measurements for the perceptual threshold of artificial- and unnatural-appearing lips.

Key Points

Question

What are the 2-dimensional quantitative measurements for lips that are perceived as attractive vs artificial?

Findings

This survey study provides quantitative data to support that a balanced augmentation of the upper and lower lips is the key to achieving attractive and natural lip enhancement. The study also shows that there is a measurable difference between people of different age groups and their perceptual threshold for artificial lips.

Meaning

Although relying on fixed guidelines for lip augmentation may not be practical or realistic, these findings provide some guidance in helping clinicians counsel their patients who are seeking lip augmentation.

Introduction

As one of the central components of facial aesthetics, full and well-defined lips impart a sense of youth, health, attractiveness, and sensuality. With the aging process, the lips undergo stereotypic changes including loss of volume and flattening of the philtrum. There is widening and effacement of contours of the Cupid’s bow, and loss of the natural “pout” of the vermillion. In addition, bony resorption associated with advanced age leads to thinning of the mandible and a decrease in the distance from the lips to the chin. The loss of dental height leads to the perception of vertical lengthening of the lips and downward laxity at the lip commissures. For patients presenting with aging lips, the goal of lip augmentation is to restore lost volume and reestablish the natural, youthful profile. In contrast, younger patients often seek lip augmentation to achieve the trendy voluptuous, full lips seen in celebrities.

Although extensive quantitative measurements and analysis have been published in the literature, these studies emphasize what constitutes ideal or attractive dimensions for the lips. The ideal proportions and measurements of the lips’ dimensions and their relation to the whole face have been studied in dental, dermatologic, and plastic surgery literature. In these studies, various methods have been described to measure changes in the lips after enhancement, including validated photonumeric rating scales, volume measurement assisted by magnetic resonance imaging, computerized 3-dimensional stereophotometry, and objective lip index measurement. Many of these studies demonstrate feasible and reliable methods to quantify the changes in the proportion and measurements of the lips.

However, in practice, to what extent the lips should be augmented to achieve the patient’s goal is mostly subjective and qualitative, based on the experience of the clinicians and the desire of the patients. The “ideal lip” is described as having full volume and proportional balance of the upper and lower lips, with a well-defined vermillion border. The challenge of lip enhancement is avoiding overtreatment, which crosses the perceptual threshold of artificial- and unnatural-appearing lips. What constitutes the perception of artificial and unnatural lips and the quantitative perceptual threshold for such lips has not been described in the literature, to our knowledge. We describe a quantitative 2-dimensional threshold for the perception of artificial- and unnatural-appearing lips.

Methods

High-resolution digital photography of a 35-year-old white woman was performed using a digital camera (Canon EOS T2i at 1/160 F10 ISO Auto; EFS 18-55) with umbrella lights for illumination. Although we began with a photograph of a 35-year-old female patient’s lips, in reality, it is an extensively digitally morphed, deidentified photograph altered to create a baseline photograph based on ideal measurements. Therefore, we determined that consent from the woman was not warranted. We cropped the frontal view of the photographs to show only the lower one-third of the face. The limits of the lower one-third of the face are the malar eminence as the lateral limit, the supranasal tip as the superior limit, and the menton as the inferior limit. The baseline lip photograph was generated using software (Uniplast for Windows; United Imaging Inc). The baseline dimensions of the lips were derived from mean measurements from textbooks and the literature. Based on the study design, we determined that institutional review board approval was not necessary because the study did not collect any identfiable data on the participants. Individuals consented to participate in the study by clicking “Yes” on the introduction page of the survey. If “Yes” was selected, the survey began. If “No” was selected, the survey was terminated and no data were collected.

In the first set of photographs, the height of the upper lip was altered at 1-mm increments up to 5 mm. The upper lateral commissure angle increased to correspond with the increments of the height of the upper lip, while the depression of midline Cupid’s bow was maintained at 1.4 mm. On the second set, the lower height was altered at 1-mm increments up to 5 mm, with corresponding adjustment to the lower lateral commissure angle. On the third set, the heights of both upper and lower lips were altered at 1-mm increments up to 5 mm. For the fourth set, we altered the shape of the Cupid’s bow. The distance between the peaks of the Cupid’s bow was set at 17.3 mm. This measurement makes the distance between the lateral commissure to the peak of the Cupid’s bow and the distance between the 2 peaks of the Cupid’s bow equal. The lateral commissure angle was 46° to accommodate the change of width of the Cupid’s bow. From the baseline lips, the heights of both the upper and lower lips were then altered simultaneously at 1-mm increments up to 5 mm.

For the fifth set of baseline lips, we extensively altered the shape of the Cupid’s bow. The distance between the peaks of the Cupid’s bow was set at 26 mm. This measurement makes the length of the entire Cupid’s bow equal to one-half of the entire length of the upper lip. The lateral commissure angle was 60° to accommodate the change in the width of the Cupid’s bow. Next, the heights of both the upper and lower lips were altered simultaneously at 1-mm increments up to 5 mm. In all sets of photographs, the overall width of the lip was maintained at 52 mm.

Photographs were uploaded to an internet-based questionnaire survey service (https://www.surveygizmo.com; Widgix LLC). Participants in the analysis and the survey, which took place from December 1, 2013, to January 30, 2014, were males and females from the lay public between the ages of 13 and 73 years. The link to the survey led to background introduction and instructions of the study. The next page displayed a set of sample photographs of the lips and explained that each photograph would be presented after 5 seconds. Next, sample questions were provided asking participants to determine whether the lips appeared natural or artificial. Additional information was collected on the age and sex of participants. Fields were provided to allow comments on technical problems and questions about the study.

Thirty images (5 sets each with baseline, 1, 2, 3, 4, and 5 mm of increment) were presented for 5 seconds in a randomized sequence. In addition, the baseline image was presented 5 more times in a randomized sequence to serve as a duplicate to determine intraobserver consistency. Photographs were presented at a resolution of 842 × 368 pixels. The photograph was displayed on the screen for 5 seconds on a timer. After 5 seconds, the next screen containing 2 questions with binary answer choices was displayed automatically. The first question stated, “Do you think these lips received any type of treatments to enhance their appearance?” The participants were prompted to select 1 of the 2 answer choices: “Yes” or “No.” The second question asked, “Do you feel that these lips appear attractive and natural, OR artificial and unnatural?” The participants were prompted to select 1 of the 2 answer choices: “Attractive and Natural” or “Artificial and Unnatural.” Participants were able to proceed to the next set of photographs and question sets only after they completed the 2 questions.

The data set was downloaded into an Excel spreadsheet (Microsoft Corp) for analysis. Based on the demographic information, participants were divided into 2 groups based on their ages. The χ2 test was performed to determine statistical significance of the difference between the 2 age groups. P values were 2-tailed and considered significant at P < .05.

Results

A total of 101 complete responses with unique IP addresses were collected during a 27-day period. The mean time for volunteers to complete the survey was 6.8 minutes. Three responses were excluded from the analysis because the duration of the survey exceeded 30 minutes, which was 2 SDs beyond the mean duration of the survey. Among the 98 participants with usable responses, there were 76 female and 22 male participants, with ages ranging from 17 through 73 years. Forty-nine participants (50%) were in the age group of 17 to 40 years (mean age, 33 years), and the other 49 participants were in the age group of 41 to 73 years (mean age, 52 years).

The participant responses were plotted against each 1-mm increment of lip height. The first part of the response was related to whether the observers thought that the model’s lips “received any types of treatments to enhance their appearance.” The response choice was binary, as already described. The second part of the response was whether the observers thought that the model’s lips “appear artificial and unnatural,” again with a binary response choice as already described.

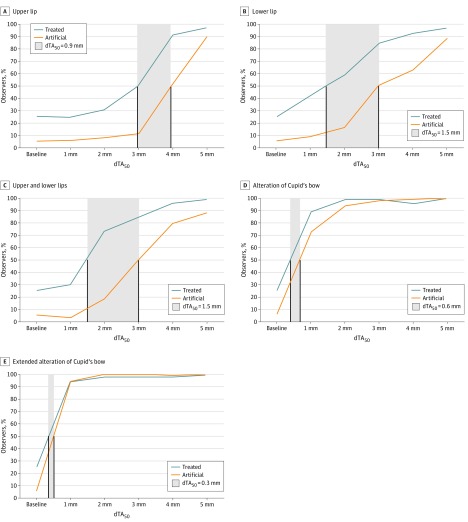

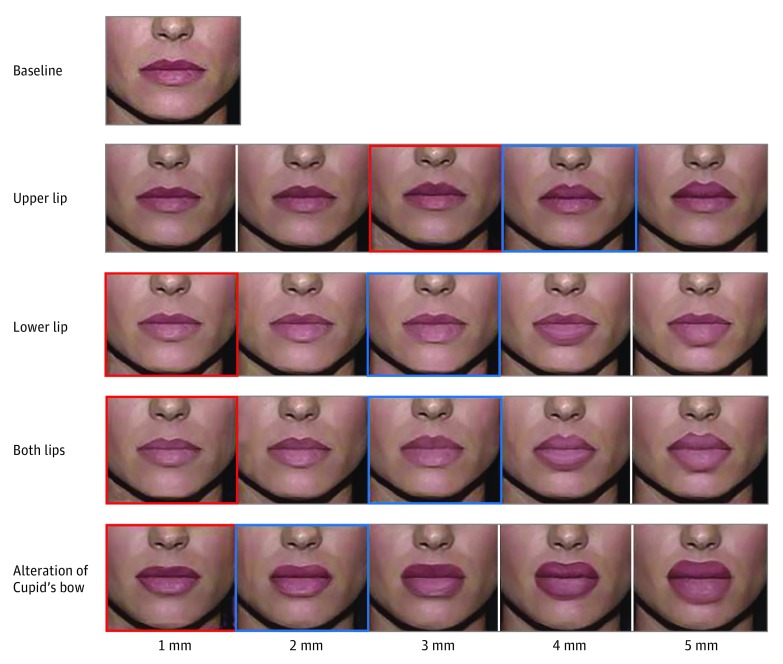

We determined the measurement of each lip at which 50% of the observers perceived the lips as receiving treatment and 50% of the observers perceived the lips as being artificial. The difference in these 2 measurements was defined as dTA50; this value represents the threshold differential between perception of treated lips and artificial lips for 50% of the observers. For each subset of lip alterations (upper lip only, lower lip only, upper and lower lips together, alteration of the Cupid’s bow, and extended alteration of the Cupid’s bow), we determined the dTA50 (Figure 1). Figure 2 shows the actual photographs of each subset of lip alterations when 50% of the observers perceived them either as treated and attractive or as artificial and unnatural.

Figure 1. Threshold Differential Between Perception of Treated Lips and Artificial Lips.

The blue line represents the percentage of observers who thought that the lips appeared treated. The orange line represents the percentage of observers who thought that the lips appeared artificial. dTA50 indicates the threshold differential between perception of treated and artificial lips for 50% of participants, indicated by the grey area between the 2 vertical black lines. dTA50 = 0.9 mm for upper lip only, 1.5 mm for lower lip only, 1.5 mm for upper and lower lips together, 0.6 mm for alteration of Cupid’s bow, and 0.3 mm for extended alteration of Cupid’s bow.

Figure 2. Photographs of the Lips Used in the Survey.

The images in the red boxes were considered treated and attractive. The images in the blue boxes were considered unnatural and artificial.

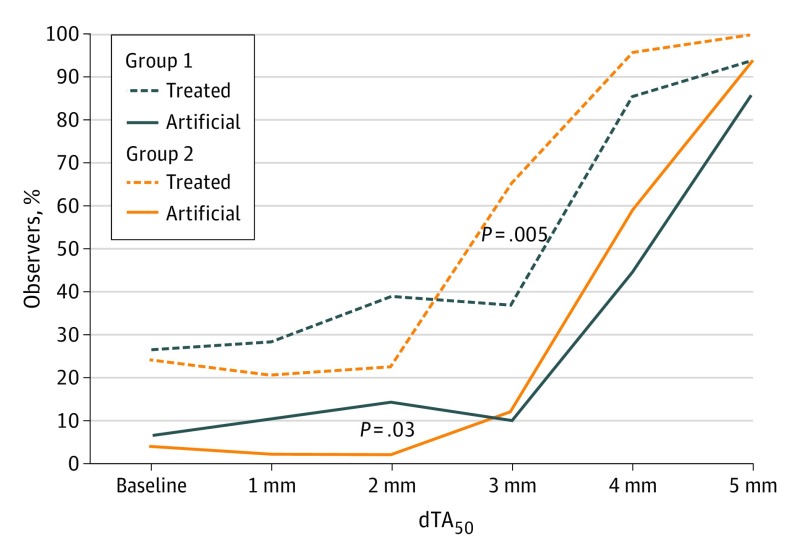

We wanted to determine whether the age of the observers would have any effect on the perception of the lips. The responses were divided into 2 groups based on the age of the observers. Group 1 consisted of younger observers between the ages of 17 and 40 years (mean age, 33 years; n = 49). Group 2 consisted of older observers between the ages of 41 and 73 years (mean age, 52 years; n = 49). Similar to part 1, we plotted the data for each subset of lip alterations (upper lip only, lower lip only, upper and lower lips together, alteration of the Cupid’s bow, and extended alteration of the Cupid’s bow). Next, we determined the dTA50 values for each subset of lip alterations for each group.

Small differences were noted between the perception of the lips for each age group, but the statistically significant difference was observed when only the upper lip was altered (Figure 3). The difference in responses of those who perceived the lips as treated and enhanced was statistically significant at 3 mm between the 2 groups (P = .005 using χ2 test at 8 with 1 df). The difference in responses of those who perceived the lips as artificial and unnatural was statistically significant at 2 mm between the 2 groups (P = .03 using the χ2 test at 4.9 with 1 df).

Figure 3. Effect of Age of the Observers on the Perceptual Threshold of the Lips.

Group 1 consisted of younger observers between the ages of 17 and 40 years (mean age, 33 years; n = 49). The dashed blue line indicates observers in group 1 who considered the lips in the images to be treated; the solid blue line indicates observers in group 1 who considered the lips in the images to be artificial. The threshold differential between perception of treated and artificial lips for 50% of participants (dTA50) in group 1 was 0.89 mm. Group 2 consisted of older observers between the ages of 41 and 73 years (mean age, 52 years; n = 49) The dashed orange line indicates observers in group 2 who considered lips in the images to be treated; the solid orange line indicates observers in group 2 who considered the lips in the images to be artificial. The dTA50 in group 2 was 1.15 mm.

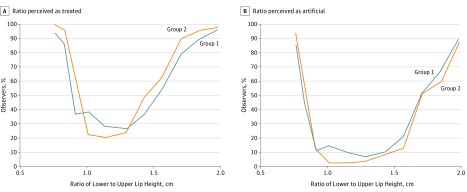

Next, we wanted to examine the effect of the upper to lower lip ratio on the perceptual threshold. The height of the lower lips ranged from 9.3 to 14.3 mm and the height of the upper lips ranged from 7.2 to 12.2 mm. The height ratio of the lower to upper lips ranged from 0.76 to 1.99. There was no difference in perceptual threshold for either the treated or the artificial-appearing lips between the 2 age groups. Fifty percent of observers in both age groups responded that the lips appeared treated if the ratio of lower to upper lips was either less than 0.92 or greater than 1.48. Meanwhile, 50% of responders in both age groups perceived that the lips appeared artificial if the ratio of lower to upper lips was either less than 0.85 or greater than 1.7 (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Effect of the Upper and Lower Lip Ratio on Perceptual Threshold.

A, Ratio of lower lip to upper lip heights that were perceived as treated. The blue line represents group 1 (mean age, 32.5 years; n = 49) and the orange line represents group 2 (mean age, 52 years; n = 49). B, Ratio of lower lip to upper lip heights that were perceived as artificial. The blue line represents group 1 and the orange line represents group 2.

Discussion

Aesthetic augmentation of lips is a challenging procedure that requires technical and artistic prowess for facial plastic surgeons. Numerous types of filler products and surgical techniques have been described to achieve youthful and voluptuous lip enhancement. One of the main challenges for clinicians is to know when to stop treating the lips before the results appear artificial and unnatural. In the clinical setting, guidelines for lip augmentation are mostly determined by the subjective assessment and experience of the clinician and the wishes of the patients. Despite the best intentions, this decision can sometimes lead to misguided and unintended consequences. This study aimed to determine the quantitative measurement of the ideal profile for lip augmentation where observers perceived the lips as treated and natural. Beyond this measurement threshold, the lips may be perceived as unnatural and artificial.

Several key findings from this study have direct clinical implications. For filler treatment of senile lips, we typically inject between 0.5 and 1 mL of hyaluronic acid gel injection filler via either a 27-gauge syringe needle or blunt tip microcannula. The advantages of using a microcannula for lip augmentation include reduced risk of bleeding and bruising and intra-arterial injection. The treatment always starts with the upper lip because if the upper lip is unintentionally injected with too much filler, one can compensate by slightly overtreating the lower lip to maintain the ideal proportion. Based on our study, overtreatment of the upper lip alone presents with a narrow margin (dTA50, 0.9 mm) for artificial appearance compared with when both the upper and lower lips are overtreated (dTA50, 1.5 mm).

There are 2 distinct groups of patients who inquire about lip enhancement: younger patients who want more full and voluptuous lips and older patients with poor definition of the vermillion contour and atrophic lips who want improvement in definition and vertical rhytids. The data from this study suggest that there is a measurable difference between people of different age groups and their perceptual threshold for overtreated and artificial lips. The difference in the perceptual threshold between the 2 age groups (20-40 years vs >40 years) is most significant for the upper lip measurement. As expected, the younger group’s perception of natural and attractive appears to be for a bigger lip than the older group.

One interesting finding is that the artificial appearance of an overenhanced upper lip can be corrected by overenhancing the lower lip, as long as the height of the lower lip is 1.6 times the height of the upper lip. The ideal ratio in heights of the upper to lower lips as 1:1.618 has often been described in textbooks and the literature as the divine proportion or the golden ratio. Based on our study, the perceptual threshold for attractive lips and artificial lips is not determined strictly on the dimension of the lips alone. The key to achieving an attractive and natural lip enhancement is to perform a balanced augmentation of the upper and lower lips.

Because the lips are complex 3-dimensional structures, any enhancements, either nonsurgical or surgical treatments, will influence the height, the width, the projection, the change in the angle of the lip commissure, the curvature of the Cupid’s bow, and the contour of the philtrum and vermillion lines. Our study was designed to determine how the layperson would perceive the appearance of various lips. The most natural setting for viewing lips during a routine encounter is the frontal view. We decided to limit the effect of changes to the height of the upper and/or lower lips and the shape of the Cupid’s bow because those alterations can be generated and controlled more precisely on frontal view photographs.

Limitations

We recognize several limitations with this study. Cultural and ethnic background can influence aesthetic perception. Because we demonstrated differences in the perception of lips between different age groups of observers, we expect that there will be significant differences in perception for observers based on their cultural and ethnic backgrounds. We also considered that geographical background will influence observers’ perceptual threshold.

The dynamic characteristics of the lips and their effect on the perception of lips were not discussed in this study. Following lip enhancement procedures, particularly after surgical treatments such as V-Y lip advancement, one may experience some changes in the natural movement of the lips. Whether asymmetric movement or an unnatural contour of the moving lip plays a key role in perceived artificiality is an important and complex problem that warrants further investigation. Application of neurotoxins around the mouth and their effect on perception of dynamic lip movement is another area that needs further investigation.

Conclusions

The lips play a major role in the overall aesthetic appearance of the face. As with all facial structures, the relative proportions of all the various components contribute to our collective concept of beauty. If any of the individual components, whether the eyes, nose, ears, or lips, become too large (or too small), then the harmony is disturbed and the end result falls outside the limits of aesthetic norms.

In practice, the burden lies with the clinician to counsel the patient and inform him or her when more enhancement is too much, which can be challenging, particularly when patients, often misguided by popular trends, insist on more enhancement. We recognize that quantitative measurement of the lips as a fixed guideline for lip augmentation is neither practical nor realistic. There are too many variables to assume that a strict set of measurements can predict the subjective perception of the lips. The goal of this study was to provide some quantitative measurements to help guide clinicians in counseling their patients who are seeking lip augmentation.

References

- 1.Segall L, Ellis DAF. Therapeutic options for lip augmentation. Facial Plast Surg Clin North Am. 2007;15(4):485-490, vii. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ferrario VF, Sforza C, Serrao G. A three-dimensional quantitative analysis of lips in normal young adults. Cleft Palate Craniofac J. 2000;37(1):48-54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sawyer AR, See M, Nduka C. 3D stereophotogrammetry quantitative lip analysis. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2009;33(4):497-504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sarnoff DS, Gotkin RH. Six steps to the ‘perfect’ lip. J Drugs Dermatol. 2012;11(9):1081-1088. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rossi AB, Nkengne A, Stamatas G, Bertin C. Development and validation of a photonumeric grading scale for assessing lip volume and thickness. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2011;25(5):523-531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Carruthers A, Carruthers J, Hardas B, et al. A validated lip fullness grading scale. Dermatol Surg. 2008;34(suppl 2):S161-S166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kane MA, Lorenc ZP, Lin X, Smith SR. Validation of a lip fullness scale for assessment of lip augmentation. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2012;129(5):822e-828e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jacono AA, Quatela VC. Quantitative analysis of lip appearance after V-Y lip augmentation. Arch Facial Plast Surg. 2004;6(3):172-177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jacono AA. A new classification of lip zones to customize injectable lip augmentation. Arch Facial Plast Surg. 2008;10(1):25-29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mandy S. Art of the lip. Dermatol Surg. 2007;33(4):521-522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rohrich RJ, Reagan BJ, Adams WP Jr, Kenkel JM, Beran SJ. Early results of vermilion lip augmentation using acellular allogeneic dermis: an adjunct in facial rejuvenation. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2000;105(1):409-416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Guerrissi JO. Surgical treatment of the senile upper lip. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2000;106(4):938-940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lassus C. Restoration of the lip roll with Gore-Tex. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 1997;21(6):430-432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Glogau RG, Bank D, Brandt F, et al. A randomized, evaluator-blinded, controlled study of the effectiveness and safety of small gel particle hyaluronic acid for lip augmentation. Dermatol Surg. 2012;38(7, pt 2):1180-1192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lemperle G, Sadick NS, Knapp TR, Lemperle SM. ArteFill permanent injectable for soft tissue augmentation, II: indications and applications. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2010;34(3):273-286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Maloney BP, Truswell W IV, Waldman SR. Lip augmentation: discussion and debate. Facial Plast Surg Clin North Am. 2012;20(3):327-346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.DeJoseph LM. Cannulas for facial filler placement. Facial Plast Surg Clin North Am. 2012;20(2):215-220, vi-vii. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Niamtu J., III Filler injection with micro-cannula instead of needles. Dermatol Surg. 2009;35(12):2005-2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wong WW, Davis DG, Camp MC, Gupta SC. Contribution of lip proportions to facial aesthetics in different ethnicities: a three-dimensional analysis. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2010;63(12):2032-2039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Keller G. Considerations in V-Y lip augmentation. Arch Facial Plast Surg. 2004;6(3):179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lemperle G, Anderson R, Knapp TR. An index for quantitative assessment of lip augmentation. Aesthet Surg J. 2010;30(3):301-310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Klein AW. In search of the perfect lip: 2005. Dermatol Surg. 2005;31(11, pt 2):1599-1603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bisson M, Grobbelaar A. The esthetic properties of lips: a comparison of models and nonmodels. Angle Orthod. 2004;74(2):162-166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]