Abstract

Objective

To identify and classify quality of life (QoL) tools for assessing the influence of neurogenic bladder after spinal cord injury/disease (SCI).

Design

Systematic Review

Methods

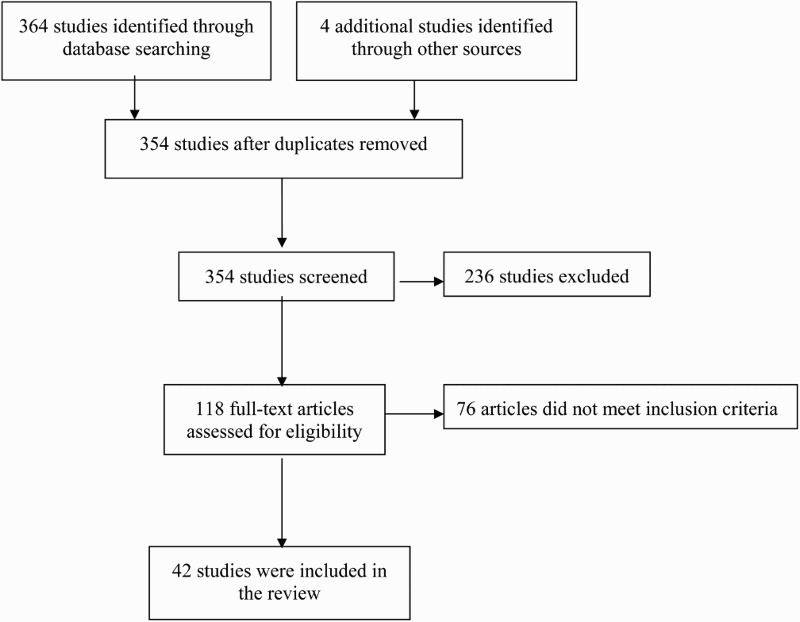

Medline/Pubmed, CINAHL, and PsycInfo were searched using terms related to SCI, neurogenic bladder and QoL. Studies that assessed the influence neurogenic bladder on QoL (or related construct) in samples consisting of ≥50% individuals with SCI were included. Two independent reviewers screened titles and abstracts of 368 identified references; 118 full-text articles were assessed for eligibility, and 42 studies were included. Two reviewers independently classified outcomes as objective (societal viewpoint) or subjective (patient perspective) using a QoL framework.

Results

Ten objective QoL measures were identified, with the Medical Outcomes Short Form (SF-36/SF-12) used most frequently. Fourteen subjective QoL measures were identified; 8 were specific to neurogenic bladder. Psychometric evidence for SCI-specific neurogenic bladder QoL tools was reported for the Quality of Life Index (QLI), Qualiveen, Bladder Complications Scale, Spinal Cord Injury-Quality of Life (SCI-QOL) Bladder Management Difficulties, and the SCI-QOL Bladder Management Difficulties-Short Form. The QLI and Qualiveen showed sensitivity to neurogenic bladder in experimental designs.

Conclusion

Several objective and subjective tools exist to assess the influence of neurogenic bladder on QoL in SCI. The QLI and Qualiveen, both subjective tools, were the only validated SCI-specific tools that showed sensitivity to neurogenic bladder. Further validation of existing subjective SCI-specific outcomes is needed. Research to validate objective measures of QoL would be useful for informing practice and policy related to resource allocation for bladder care post-SCI.

Keywords: Systematic review, Spinal cord injury, Neurogenic bladder, Quality of life

More than 80% of individuals with spinal cord injury/disease (SCI) experience neurogenic bladder resulting from neurological impairments that contribute to neurogenic detrusor overactivity +/-sphincter dysynergia, or detrusor areflexia.1 Following SCI onset, individuals with SCI have an increased risk of bladder complications for the balance of their lives; these consequences include urinary incontinence, recurrent urinary tract infections, vesicoureteral reflux, kidney and bladder stones, and high detrusor pressures leading to renal failure. Despite effective bladder management programs that lower the associated risk of morbidity and mortality, physical and practical restrictions due to the impairment often persist.

Advances in medical care have extended individual life spans in persons with SCI, increasing the importance of understanding and promoting long-term psychological and social well-being.2 Neurogenic bladder continues to negatively impact psychological and social domains, adversely influencing quality of life (QoL) and social participation.1,3 However, personal roles and social activities can be maintained with treatment.2

Measures of QoL provide a meaningful way to document individual progress and response to treatment, beyond the limited traditional measures of mortality and morbidity. Thus, advances in medical and rehabilitative care related to neurogenic bladder necessitate an understanding of the effect on the QoL of individuals with SCI. Our understanding of how to improve QoL is limited in part by our lack of ability to effectively measure QoL specific to neurogenic bladder.

Condition-specific QoL outcome measurement is confounded by several theoretical and measurement issues. From a theoretical perspective, a clear definition of QoL and how to measure it is lacking.4 QoL is commonly used synonymously with various terms, including life satisfaction, health-related QoL (HRQoL), subjective well-being, physical functioning and participation.5 With regard to measurement issues, Hitzig et al. have described how the presence of one or more secondary health conditions, common among individuals with SCI (e.g. pressure ulcers, spasticity), may minimize the sensitivity of a QoL outcome tool to measure the impact of a specific condition (e.g. impact of neurogenic bladder on QoL).6 Moreover, tools that are not developed specifically for SCI lack reliability and validity for application in SCI populations.

Based on recommendations for accurately measuring QoL,7 one suggested approach is that measures should be selected according to the domains that they evaluate and the intended population and impairments.6 In this case, descriptions of neurogenic bladder relative to SCI should be appropriately characterized and included in the QoL outcome tool. To achieve this goal, investigators must have a clear understanding of conceptual and measurement issues related to QoL (e.g. QoL specific to neurogenic bladder).

Dijkers’ QoL framework provides a promising framework for classifying and understanding QoL outcome tools.4 Dijkers’ model distinguishes between objective and subjective outcomes, an issue that is becoming of increasing importance in the field.8 Objective dimensions refer to an outsider's view of health based on observable life conditions or physical functioning, such as possessions or achievements.9 Conversely, subjective dimensions of QoL assess the individuals’ assessment of discrepancy between standards, goals, values, and the actual situation or accomplishments.9,10 Both approaches have strengths and weaknesses that should be taken into account to ensure that the QoL measures employed are congruent with the intended goals and outcomes of the project, and are meaningful to the target audience to whom the results will be delivered. Past work by our group has successfully applied this framework to other SCI-related secondary health conditions.6,11

The distinctions between objective and subjective measures are only beginning to emerge within the field of SCI, but are not applied consistently. There is a need to improve our conceptual understandings of QoL specific to neurogenic bladder in SCI to ensure that suitable outcome measures are used in combination with appropriate research design. To date, there has been limited systematic synthesis of outcome tools that the influence of neurogenic bladder on QoL in SCI populations or on the appropriateness of QoL measures for assessing neurogenic bladder following SCI. Therefore, the purpose of this study was to: 1) complete a systematic review to identify outcome measures that assess the influence of neurogenic bladder on QoL and related constructs (e.g. social participation) after SCI; 2) summarize the psychometric properties of each tool; and 3) classify each outcome according to Dijkers’ model.

Methods

A systematic review of literature published from 1950 to 2015 was conducted using electronic databases (MEDLINE, Pubmed, CINAHL, and PsycINFO). Boolean logic was applied to combine the key word spinal cord injuries and its variants with the following search terms: urinary bladder OR neurogenic bladder OR urinary incontinence OR neurogenic detrusor overactivity, AND quality of life OR participation OR activities of daily living OR personal satisfaction. The reference lists of each article were hand-searched to identify additional relevant articles. Studies written in English that comprised an adult sample (≥18 years of age) with at least 50% of participants with SCI that included QoL or related (e.g. participation) outcomes specific to neurogenic bladder were included. Studies were excluded if the sample consisted of participants with pediatric-onset SCI, or if the outcome was considered a global construct of QoL or participation after SCI (e.g. QoL outcome was not tied to neurogenic bladder). Qualitative studies were excluded.

Two raters independently conducted searches, and then rated the titles and abstracts. Consensus on abstracts was attained, and then relevant full-text articles were abstracted. If consensus could not be reached regarding article inclusion, a third rater was available for consultation. Descriptive information related to study design, participants, outcomes and related findings were abstracted into a summary table (Table 1). QoL outcomes were then classified according to Dijkers’ theoretical framework4 by one rater, and then verified by a second rater (Table 2).

Table 1.

Summary of all studies identified on neurogenic bladder and QoL post-SCI (n = 42)

| References | Research design/Population/Objective; QoL outcome measure | Findings |

|---|---|---|

| Akkoç et al.32 |

Design: Cross-sectional Population: 195 patients (145 men) with SCI (AIS A-E), mean age 38.2 ± 14.0, mean YPI 54.9 ± 60.0 months. Objective: To investigate the effects of different bladder management methods on QoL in SCI. QoL Outcome Measures: KHQ |

|

| Anson et al.37 |

Design: Cross-sectional & longitudinal survey Population: 125 persons with SCI, 18 yrs + & YPI > 1 yr. Objective: To explore relationships among social support, adjustment & secondary complications in persons with SCI. QoL Outcome Measures: QLI-SCI; RSS Scale. |

|

| Bonniaud et al.21 |

Design: Longitudinal Population: 128 (98 male, 43.5 ± 15.9 years of age) Italian-speaking individuals with SCI Objective: To assess reliability, validity & responsiveness of the Italian version of the Qualiveen. QoL Outcome Measures: Qualiveen; SF-12; Global rating of HRQL. |

|

| Böthig et al.27 |

Design: Retrospective design Population: 56 high-tetraplegic (AIS A-C) patients (40 men), mean age 45 (range 17–78); 38 SPC, 12 CIC, 2 transurethral catheter, 2 reflex voiding by suprapubic taping, 2 CIC per umibilical stoma. Objective: To identify the correlation between bladder management & age in high-tetraplegic patients; Toexamine the relationship between urological complications (SPC & CIC) & QoL. QoL Outcome Measures: ICIQ-SF |

|

| Brillhart38 |

Design: Cross-sectional survey Population: 230 persons with SCI (173 men) with SCI (tetraplegia, paraplegia), mean age 44.6 ± 14.2, mean YPI 12.2 ± 10.6. Objective: To investigate QoL & life satisfaction among persons with SCI requiring various types of urinary management. QoL Outcome Measures: SWLS; QLI-SCI. |

|

| Cameron et al.12 |

Design: Longitudinal (Inception cohort) study Population: 24,762 new SCI – 7510 included in psychosocial analyses (80% male) Objective: Indwelling catheter (urethral or supra-pubic), spontaneous voiding (continent with no collection device), condom catheterization (with or without sphincterotomy) & CIC (with or without bladder augmentation). QoL Outcome Measures: SWLS; CHART; SF-36 (perceived health status question only). |

|

| Chen et al.23 |

Design: Randomized controlled trial Population: 72 Patients with SCI (43 men) (AIS A-E), mean age 41.5 (range, 22–74), mean YPI 8.7 ± 8.1; 47 (65.3%) used periodic or intermittent CIC. All subjects had urodynamic DO or ↑ detrusor tonicity without anatomical bladder outlet obstruction or intrinsic sphincter deficiency. Objective: To investigate the therapeutic effects of repeated detrusor BoNT-A injections on treatment outcomes, QoL & GFR in chronic Patients with SCI with neurogenic lower urinary tract dysfunction & urinary incontinence. QoL Outcome Measures: UDI-6; IIQ-7; IPPS-QoL |

|

| Chen et al.24 |

Design: Quasi-experimental (pre-post) Population: 38 patients (17 men) with SCI (AIS – Non-A vs A), mean age 40.1 ± 12.4 (range 20–72), mean YPI 10.3 (range 1–35); All patients had NDO & different types of DSD. Objective: To investigate the therapeutic effects of detrusor BoNT-A with or without DSD (spincter dysynergia) in patients with different levels of SCI. QoL Outcome Measures: UDI-6; IPPS-QoL |

|

| Chen et al.43 |

Design: Quasi-experimental (pre-post) Population: 108 patients (81 men) with SCI (AIS – complete and incomplete), mean age 40.1 (range 16–78); All patients had NDO. Objective: To provide a comprehensive experience of BTX-A injected into the detrusor muscle in patients with SCI causing neurogenic DO. QoL Outcome Measures: I-QoL; Patient satisfaction |

|

| Costa et al.34 |

Design: Cross-sectional survey Population: 281patients (78% men) with SCI, mean age 41 (range 17–87), mean YPI 11 (range 1–49). Objective: To develop and validate a questionnaire suitable for patients with SCI with urinary disorders. QoL Outcome Measures: Qualiveen. |

|

| Craven et al.30 |

Design: Cross-sectional survey Population: 357 person (218 men) with SCI (AIS A-D), mean age 54.0 (range, 24–89), mean YPI 19.3 (range 2–65). Objective: To describe the relationships between secondary health conditions & health preference post-SCI. QoL Outcome Measures: HUI-3. |

|

| Ge et al.44 |

Design: Quasi-experimental (pre-post) Population: 22 (24–2 drop-outs) patients with SCI, (4 female); mean (SD) age = 42.6 (12.4) years. 13 AISA-A, 3 AISA-B, 5 ASIA C, 3 ASIA D. Objective: Evaluate the effects of Botulinum Toxin A injection into the detrusor muscle on various voiding parameters in spinal cord injured patients with neurogenic detrusor hyperreflexia QoL Outcome Measures: I-QoL; Patient satisfaction. |

|

| Gurcay et al.13 |

Design: Cross-sectional study Population: 54 Patients with SCI (37 male, 33.87 ± 10.34 years of age) Objective: To assess QoL in SCI, including clinical characteristics (i.e. bladder incontinence). QoL Outcome Measures: SF-36 |

|

| Hicken et al.22 |

Design: Case-control study Population: 53 matched pairs with SCI (AIS A-D): 1) Bladder/bowel dependent individuals (49 men), mean age 37.02 ± 12.94. 2) Bladder/bowel independent individuals (49 men), mean age 36.77 ± 13.20. YPI divided into 4 groups (1, 2–5, 6–15, > 16 yrs); Groups matched on age, sex, education, race & lesion level. Objective: Examined the QoL among individuals with SCI requiring assistance for bowel & bladder management compared to those with independent control of their bladder and bowel. QoL Outcome Measures: CHART; SWLS; SF-12. |

|

| Kachourbos and Creasey52 |

Deisgn: Cross-sectional survey (post-intervention) Population: 16 persons with SCI, 6 months post-surgery. Objective: To assess recollections of health and QoL pre-operatively in relation to bladder & bowel care & to rate changes in QoL post-implant of an implantable stimulator. QoL Outcome Measures: Study specific questionnaire. |

|

| Kuo et al.25 |

Design: Quasi-experimental (time-series) Population: 38 high-tetraplegic (AIS A-C) patients (21 men), mean age 37 ± 23 (range 18–63), mean YPI 7 (range 2–23); All patients had DSD. All patients voided by reflex or abdominal stimulation with or without CIC. Objective: To investigate the therapeutic effects of repeated BoNT-A injections on urinary incontinence & renal function in patients with chronic SCI. QoL Outcome Measures: UDI-6; IIQ-7; IPPS-QoL; PPBC. |

|

| Kuo26 |

Design: Quasi-experimental (pre-post) Population: 33 (22 males) patients with SCI, median age 41 yrs (range 23–71 yrs). All patients had DSD & urinary incontinence without difficult urinarion (n = 3), difficult urination without incontinence (n = 13) or both urinary incontinence with difficult urination (n = 17). Objective: To investigate satisfaction with urination QoL after treatment with urethral sphincter BoNT-A injection for difficult urination in patients with spinal cord lesions & DSD. QoL Outcome Measures: UDI-6; IIQ-7. |

|

| Kuo39 |

Design: Retrospective study Population: 251 (212 men) Patients with SCI, YPI 7.6 ± 5.8 yrs. Objective: To assess the QoL with regard to urination after active urological management from 1988 to 1996 in eastern Taiwan. QoL Outcome Measures: QLI-SCI. |

|

| Liu et al.14 |

Design: Cross-sectional study Population: 142 people with SCI (105 male, mean (SD) age = 45.2 (14.6) years. Objective: 1) To assess the relationship between bladder management methods & the HrQoL in patients with SCI; 2) To identify any correlation between the two questionnaires used to assess the QoL. QoL Outcome Measures: SF-36; KHQ |

|

| Lombardi et al.15 |

Design: Retrospective study Population: 75 people with SCI Objective: To assess the concomitant clinical improvement in incomplete SCI with NLUTSs using sacral neuromodulation for neurogenic bladder & NLUTSs. QoL Outcome Measures: SF-36. |

|

| Luo et al.46 |

Design: Cross-sectional survey Population: 180 patients (98 men) with SCI (AIS A-E), age range 41–64, mean YPI 8.7 ± 8.1; 62 patients (34.44%) able to void normally, 65 (36.11%) required manually assisted voiding, 29 (16.11%) required catheterization, & 24 (13.33%) used a urine-collecting apparatus. Symptomatic UTI prevalence was 43.89%. Objective: To assess the relationship between bladder management methods, symptomatic UTI & QoL. QoL Outcome Measures: WHOQOL-BREF. |

|

| Martens et al.16 |

Design: Cross-sectional design Population: BrindleyGroup -46 (36 men) patients with complete SCI, mean age 48 (range 33–67), mean YPI 21 (range 5–40). Rhizotomy Group - 27 patients (22 men) with complete SCI, mean age 47 (age range 26–66), mean YPI 19 (YPI range 7–36). Control Group) 28 patients with complete SCI with DO, mean age 42 (range 20–75), mean YPI 9 (range 2–32). Objective: To determine the effects on QoL of a Brindley procedure (enables micturition, defecation, & penile erections) in complete SCI compared to a matched control group. QoL Outcome Measures: Qualiveen; SF-36. |

|

| Moreno et al.50 |

Design: Quasi-experimental (pre-post) Population: 3 women with AIS A tetraplegia with end-stage neurogenic vesical dysfunction that was complicated by a urethra destroyed by chronic indwelling catheter drainage. Age & YPI presented individually. Objective: Pre and post-evaluation of continent urinary diversion. QoL Outcome Measures: Non-standardized study-specific questionnaire. |

|

| Noonan et al.17 |

Design: Cross-sectional survey Population: 70 persons (57 men) with central cord syndrome, mean age at injury 45 ± 18 (range 13–91), mean age at follow-up 51 ± 18 (range 19–95). Objective: To determine the effect of associated SCI conditions on health status & QoL. QoL Outcome Measures: SF-36; Global rating of QoL & patient satisfaction. |

|

| Oh et al.18 |

Design: Cross-sectional study Population: Group 1 - 132 patients (81 men) with SCI (tetraplegia, paraplegia) using CIC, mean age 41.8 (range 18–80). Group 2 -150 controls (90 men). Groups matched on geographical region, age & sex. Objective: To determine the psychological & social status of patients using CIC for neurogenic bladder according to HrQoL. QoL Outcome Measures: SF-36. |

|

| Pannek et al.35 |

Design: Cross-sectional survey Population: 41 (31 men) patients with SCI (tetrapleiga, paraplegia), mean age 39.5 ± 14 (range 18–72), mean YPI 14 ± 11 (range 1–22). Objective: To analyze the influence of bladder management on well-being by correlating the objective urodynamic results of bladder treatment with perceived QoL in patients with SCI. QoL Outcome Measures: Qualiveen. |

|

| Patki et al.28 |

Design: Quasi-experimental (pre-post) Population: 11 women with paraplegia (incomplete, complete), mean age 56.7 ± 15; All patients had neurogenic DO or USI. Objective: To examine efficacy of a combination of botox bladder injections & transobturator or tension free vaginal tape on QoL. QoL Outcome Measures: ICIQ-SF |

|

| Patki et al.29 |

Design: Quasi-experimental (pre-post) Population: 37 patients (24 men) with SCI (incomplete, complete, tetraplegia, paraplegia), mean age 39.4 (range 16–77), mean YPI 7 (range 3–11); All patients had neurogenic DO & NLUTs. Objective: To assess whether BTX-A can be used as a daycase treatment for drug-resistant neurogenic DO in patients with SCI. QoL Outcome Measures: ICIQ-SF. |

|

| Pazooki et al.51 |

Design: Retrospective study Population: 10 (5 men) patients with SCI (tetraplegia, paraplegia), mean age at operation 41.6 (range 26–64). Objective: To examine the functional results & effect on QoL of continent cutaneous urinary diversion in Patients with SCI. QoL Outcome Measures: Non-standardized study specific questionnaire. |

|

| Sapountzi-Krepia et al.33 |

Design: Cross-sectional survey Population: 98 persons with post-traumatic paraplegia (61 men), mean age 31.35. Objective: To measure the impact of pressure sores & UTI on the everyday life activities of persons with post-traumatic paraplegia. QoL Outcome Measures: SFLS. |

|

| Schurch et al.45 |

Design: Randomized double-blind, multi-center, placebo-controlled study Population: 59 patients with urinary incontinence were divided into: Group 1) Patients with SCI (53 patients); All patients had DO. Group 2) Multiple Sclerosis patients (6 patients). Age range 21–73 years: Patients with SCI (50 patients); Multiple Sclerosis (6 patients). Patients were further divided into 3 treatment groups: A) BoNTA 200 U; B) BoNTA 300 U; C) Placebo. QoL data was only available for 56 (33 men) patients, Objective: To evaluate the impact of BoNT-A on the HrQOL in patients with neurogenic urinary incontinence. QoL Outcome Measures: I-QOL. |

|

| Schurch et al.19 |

Design: Randomized double-blind, multi-center, placebo-controlled study Population: 56 patients with urinary incontinence (UI) were divided into: Group 1) Patients with SCI (53 patients); Group 2) Multiple Sclerosis patients (6 patients). Patients were further divided into 3 treatment groups: A) BoNTA 200 U; B) BoNTA 300 U; C) Placebo. Objective: To evaluate the reliability, validity, responsiveness & MID of the I-QOL in patients with urinary incontinence due to neurogenic DO. QoL Outcome Measures: I-QOL; SF-36. |

|

| Taweel et al.1 |

Design: Quasi-experimental (pre-post) Population: 103 persons with SCI (32 female); mean age = 29 years (range: 18–56 years). Objective: report the effectivemess and safety of OnabotulinumtoxinA (Botox) injections in post-SCI QoL Outcome Measures: QoLVAS |

|

| Tsai et al.40 |

Design: Quasi-experimental (pre-post open-label) Population: 18 men with SCI (AIS A-C), mean age 33.8 ± 6.6, mean YPI 3.0 ± 2.1; All patients had voiding dysfunction resulting from DSD. Objective: To determine the effectiveness of a combined method for localizing external urethral sphincter for transperineal injection of BTX-A in the treatment of DSD post-SCI. QoL Outcome Measures: QLI-SCI. |

|

| Tsai et al.41 |

Design: Quasi-experimental (pre–post) Population: 22 men with SCI (AIS A-D), mean age 46.3 ± 11.9 (range 26–64), mean YPI 2.7(range 0.5–18); All patients had voiding dysfunction resulting from external urethral sphincter hypertonicity. Objective: To study the effects of pudendal nerve block with phenol on DSD in patients with SCI. QoL Outcome Measures: QLI-SCI. |

|

| Tulsky et al.42 |

Design: Mixed qualitative & cross-sectional design Population: 757 adults with SCI (79% male, 42.9 ± 15.5 years of age) subsample of 297 (78% male, 40.6 ± 15.2) with bladder complications for the Bladder Complication Scale Objective: Describe the development and psychometric properties of: 1. the Spinal Cord Injury-Quality of Life (SCI-QOL) Bladder Management Difficulties item banks 2. Bladder Complications scale. QoL Outcome Measures: SCI-QOL Bladder Management Difficulties; Bladder Complications Scale. |

|

| Vaidyananthan et al.47 |

Design: Quasi-experimental (pre-post) Population: 7 male patients with SCI (tetraplegia, paraplegia) mean age 44.3. Objective: A comparative assessment of 1) urinary continence status, 2) QoL, 3) sexuality in Patients with SCI prior to & during intermittent catheterization with adjunctive intravesical oxybutynin therapy. QoL Outcome Measures: QoLVAS |

|

| Vastenholt et al.36 |

Design: Cross-sectional survey Population: 42 patients (32 men) with SCI (tetraplegia, paraplegia), mean age 43 (23–63 yrs), meanYPI 73 months (46–498 months); All patients implanted with SARS. Objective: To assess long-term effects & QoL of using SARS in Patients with SCI. QoL Outcome Measures: Qualiveen. |

|

| Walsh et al.49 |

Design: Cross-sectional Population: 6 females with SCI (age range = 16 to 22) Objective: To evaluate the success of a continent catheterizable stoma in females with cervical SCI. QoL Outcome Measures: A study specific-survey using VAS |

|

| Westgren et al.20 |

Design: Cross-sectional survey Population: 320 persons (261 men) with SCI, mean age 42 (17–78 yrs), YPI ≤ 4 yrs & ≥ 4 yrs. Objective: To determine associations between major outcome variables after SCI & QoL. QoL Outcome Measures: SF-36. |

|

| Wielink et al.31 |

Design: Longitudinal Population: 52 patients (82% male) with complete spinal cord lesion, mean age 28 (range 16–54). Objective: To present a cost-effectiveness analysis of sacral rhizotomies & electrical bladder stimulation compared with conventional care of neurogenic bladder in persons with SCI. QoL Outcome Measures: Nottingham Health Profile; Karnofsky Performance Index; Affect Balance Scale; Non-standardized study-specific questionnaire. |

|

| Zommick et al.48 |

Design: Quasi-experimental (pre-post) Population: 21 (12 men) patients with SCI, mean age at operation 34.6 (range 17–51 yrs), mean follow-up post-surgery 59.5 mos. Objective: To determine long-term success & patient satisfaction after lower urinary tract reconstruction. QoL Outcome Measures: Non-standardized study specific questionnaire; VAS |

|

AIS = American Spinal Injury Association Impairment Scale; BoNT-A = Botulinum toxin A; BTX-A = Botulinum toxin-type A; CBC = Cystometric Bladder Capacity; CFI = Comparative Fit Index ; CIC = Clean Intermittent Catherization; CHART = Craig Handicap Assessment and Reporting Technique; DO = Detrusor Overactivity; DSD = Detrusor Sphincter Dyssynergia; FIM = Functional Independence Measure; GFR = Glomerular Filtration Rate; HrQoL = Health Related Quality of Life; HUI = Health Utilities Index; ICC = Intraclass Correlation Coefficient; ICIQ = International Consultation on Incontinence ; IIQ-7 = Incontinence Impact Questionnaire; I-QOL = Incontinence Quality of Life ; ISC = Indwelling Suprapubic Catheterization ; ITC = Indwelling Transurethral Catheterization ; KHQ = King's Health Questionnaire; MCC = Maximum Cystometric Capacity; MCS = Mental Component Score of the SF-36; MDP = Maximum Detrusor Pressure; MID = Minimally Important Difference; NLUTs = Neurogenic Lower Urinary Tract symptoms; QoL = Quality of Life; IPSS-QoL = International Prostatie Symptom Score- QoL index; Qmax = Maximum Flow Rate; Pdet.Qmax = Voiding Detrusor Pressure at Qmax; PPBC = Patient Perception of Bladder Condition; PCS = Physical Component Score of the SF-36; PVR = Post-Void Residual; RMSEA = Root Mean Square Error of Approximation ; RSS = Reciprocal Social Support; SARS = Sacral Anterior Root Stimulation; SCI = Spinal Cord Injury (ies); SCI-QLI = Spinal Cord Injury Quality of Life Index; SCI-QOL = Spinal Cord Injury Quality of Life ; SCS = Secondary Condition Scale; SF-12 = Short-Form 12; SF-36 = Short-Form 36; SFLS = Sarno Functional Life Scale; SIUP = Specific Impact of Urinary Problem; SPC = Suprapubic Catheter; SRM = Standardized Response Mean; SWLS = Satisfaction with Life Scale; UDI-6 = Urogenital Distress Inventory Short Form; USI = Urodynamic Stress Incontinence; UTI = Urinary Tract Infection; VAS = Visual Analog Scale; WHOQOL-BREF = World Health Organization Quality of Life; YPI = Years Post-Injury; 99mTc-DTPA = 99mTc-labelled diethtlenetriamine penta-acetic acid; ↑ = increased/higher; ↓ = decreased/lower.

Table 2.

Summary of outcome measures

| Outcome Tool (O- Objective; S – Subjective) |

QoL Construct |

SCI psychometrics | Format/Scoring | Burden (minutes) | Sensitive to neurogenic bladder | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | B | C | D | E | ||||||

| O | Craig Handicap Assessment and Reporting Technique (CHART) | X | X | Reliability and validity established for SCI (see Hall et al.57 for further details) | 32 items comprise 5 domains; scores in each domains range from 0 (maximal handicap) to 100 (non-disabled). Domain scores can also be combined to form a total score. Higher scores correspond to role fulfillment equivalent to that of most individuals without disabilities. |

∼15 m | +Cameron et al. 2011 +Hicken et al. 2001 |

|||

| O | Health Utility Index III (HUI-3) | X | X | X | Preliminary evidence of validity in SCI (see Mittmann et al.58 for further details) | Health utility is based on perceived level functioning over the past 4 weeks in eight health attributes (vision, hearing, speech, ambulation, dexterity, emotion, cognition, & pain. A multiplicative formula is used to calculate a score where perfect health = 1.000; death = 0.000, & negative scores reflect a health state worse than death. |

∼5–10 m | +Craven et al. 2012 | ||

| O | International Consultation on Incontinence Modular Questionnaire– Short Form (ICIQ-SF) | X | X | Not available for SCI | 3 items are summed to provide a score between 0 & 21. Higher scores reflect increased urinary incontinence and poorer QoL. | ∼5 m | -Bothing et al. 2012 +Patki et al. 2008 +Patki et al. 2006 |

|||

| O | Karnofsky Performance Scale Index | X | X | Not available for SCI | 1 item to derive a score between 0 (dead) & 100 (Normal, no complaints, no evidence of disease) that is indicative of functional performance. Scoring is usually in intervals of 10. |

NR (est < 3 m) | -Weilink et al. 1997 | |||

| O | King's Health Questionnaire | X | X | Not available for SCI | 21 items about urinary tract symptoms yield scores in 9 domains (General health perception, incontinence impact, role limitations, physical limitations, social limitations, personal relationships, emotions, sleep/energy, & severity of symptoms). Each item is rated using a 4- or 5- point likert scale. Domain scores range from 0 (best) to 100 (worst). There are 2 single-item domains (General health perceptions, and incontinence impact) and the severity of symptoms domain is score using a scale from 0 (best) to 30 (worst). |

∼5 m | +Akkoç et al. 2013 + Liu et al. 2010 |

|||

| O | Nottingham Health Profile | X | X | Not available for SCI | 46 items comprise 2 parts. Part 1–38 items in 6 subareas (energy level, pain, emotional reaction, sleep, social isolation, physical abilities). Part 2- 7-items with a yes/no response. Part 2 is not included in scoring. Weighted scores are summed, then subtracted from 100% to provide a score between 0 (poor health) and 1 (good health). |

∼10 m | -Weilink et al. 1997 | |||

| O | Sarno Functional Life Scale (SFLS) | X | X | Not available for SCI | 44 items comprise 5 elements to measure 4 qualities of performance (self-initiated, frequency, speed, efficiency) on a 5-point scale ranging from 0 (does not perform activity) to 4 (normal performance). Scores are obtained for each of the 5 elements for each of the 4 qualities. A proportion is then calculated based on of the individuals observed score compared to his/her maximal score. Functioning is assessed in 5 domains: everyday activities, indoor activities, outdoor activities, social relations, & cognitive abilities |

∼15–20 m | +Sapountzi-Krepia et al. 1998 | |||

| O | Short-Form 36 (SF-36) | X | X | Reliability and validity established for SCI (see Noonan et al.53 for further details) | 36 items comprise 8 domains (physical functioning, role limitations due to physical health problems, bodily pain, general health, vitality, social functioning, role limitations due to emotional problems & mental health). Weighted sums of each domain provide a score between 0 to 100 A physical component score (PCS) and a mental component score (MCS) can be calculated by averaging the items in the physical domains (PCS) & emotional domains (MCS). The scoring is based on population norms, mean (SD) = 50 (10). Higher scores indicate higher levels of health |

∼5–10 m | +Cameron et al. 2011 +Gurcay et al. 2010 +Liu et al. 2010 +Lombardi et al. 2011 +Martens et al. 2011 +Noonan et al. 2008 -Oh et al. 2005 +Schurch et al. 2007b +Westgren et al. 1998 |

|||

| O | Short-Form 12 (SF-12) | X | X | Construct validity established. (see Andresen et al.54 for further details) | 12 items, derived from the physical &mental domains of the SF-36. Weighted sums of each domain provide score between 0 to 100. The scoring is based on population norms, mean (SD) = 50 (10). Higher scores indicate higher levels of health |

<5 m | -Bonniaud et al. 2011 +Hicken et al. 2001 |

|||

| O | Urogenital Distress Inventory Q (UDI – 6) | X | X | Not available for SCI | 6 items about urinary problems over the previous 3 months. Each item is scored between 0 (no problem) to 3 (bothered greatly). All scores are summed and multiplied by 6, then multiplied by 25 for the scale score Higher score indicate higher disability |

∼5 m | +Chen et al. 2014 +Chen et al. 2011 +Kuo et al. 2011 -Kuo 2008 |

|||

| S | Affect Balance Scale | X | Not available for SCI | 10 statements (5 reflecting positive feelings; 5 reflecting negative feelings). The difference between the positive and negative scores is calculated to provide a score ranging from– 5 (worst) to + 5 (best). |

∼5–10 m | +Weilink et al. 1997 | ||||

| S | Bladder Complications Scale | X | Reliability and validity established for SCI (see Tulsky42 for further details) | 5 items about various bladder complications experienced ‘lately’ are given a score between 1 (never/not at all) & 5 (always/very much). Items are summed then converted to a standardized T-metric score with a mean (SD) = 50 (10). Higher scores indicate more complications. |

NR (est 5–10 m) | NR Tulsky et al. 2015 | ||||

| S | *European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer (QLQ-C30) (*QoL item only) | X | Not available for SCI | 1 item to rate overall QoL in the past week. Scores range from 1 (very poor) to 7 (excellent). | NR (est ∼ 1 m) | +Noonan et al. 2008 | ||||

| S | Incontinence Impact Q (IIQ-7) | X | X | Not available for SCI | 7 items assess influence of urinary incontinence on physical activity, travel, social/relationships, & emotional health. Each item is scored between 0 (activities not affected at al) to 3 (activities greatly affected). The average of all 7 items is multiplied by 33 1/3 for a total score out of 100. |

∼5 m | +Chen et al. 2014 +Kuo et al. 2011 +Kuo 2008 |

|||

| S | Incontinence Quality of Life Scale (I-QoL) | X | X | Reliability and validity established for SCI (see Schurch et al.19for further details) | 22 items comprise 3 subscales that assess concerns related to incontinence (avoidance and limiting behaviour; psycho-social impact; social embarrassment) Items are scored on a 5-point scale ranging from 1 (extremely concerned) to 5 (not at all concerned). Scores are then converted to a scale score ranging from 0-100, with higher scores indicating higher QoL. |

∼5 m | +Chen et al. 2011b +Ge et al. 2015 +Schurch et al. 2007 +Schurch et al. 2007b |

|||

| S | Patient Perception of Bladder Condition (PPBC) | X | Not available for SCI | A single-item tool to rate perception of urinary problems using a 6-point scale ranging from 1 (no problems at all) to 6 (many severe problems). | NR (est ∼ 1 m) | +Kuo et al. 2011 | ||||

| S | International Prostate Symptom Score-QoL index (IPSS-QoL) | X | Not available for SCI | 8-item tool 7 items rate frequency of symptoms on a scale ranging from 0 (not at all) to 5 (almost always). Score range from 0 to 35, with higher scores indicating higher frequency of urinary problems. 1 item rates QoL (feelings if current symptoms lasted for life) on a scale ranging from 0 (delighted) to 6 (terrible). |

∼8 m | +Chen et al. 2014 +Chen et al. 2011 +Kuo et al. 2011 |

||||

| S | Ferrans and Powers Quality of Life Index for Spinal Cord Injury (QLI-SCI) | X | X | X | Preliminary evidence of validity in SCI (see Hill et al.63 for further details) | 74 items comprise 2 parts: Part 1- Satisfaction (37 items) and Part 2- Importance (37 items). There are 4 subscales (Health and functioning; Socioeconomic status; Psychological and spiritual well-being; Family Relationships; and QoL) Each item is ranked on a 6 point scale ranging from 1 (Very Dissatisfied) to 6 (Very Satisfied). Scores range from 0 to 30, with higher scores reflecting higher levels of QoL. A score for total QoL or each of the sub-scales may be calculated. |

∼10 m | +Anson et al. 1993 -Brillhart 2004 +Kuo et al. 1998 +Tsai et al. 2009 +Tsai et al. 2002 |

||

| S | Qualiveen-30 | X | X | Reliability and validity established for SCI (see Bonniaud et al.21 and Costa et al.34 for further details) | 30 items comprise 4 domains: (bother with limitations, frequency of limitations, fears, and feelings). Items are scored using 5-point Likert-type scales, & scores range from 0 (no impact) to 4 (high adverse impact). Averages for each domain are calculated, with equal weighting among items. An overall QoL score can be calculated from the mean of the 4 domains, with lower scores indicating better QoL (i.e. no limitations constraints, or negative feelings). |

< 30 m | +Bonniaud et al. 2011 +Costa et al. 2001 +Martens et al. 2011 +Pannek et al. 2009 +Vastenholt et al. 2003 |

|||

| S | Reciprocal Social Support (RSS) | X | X | Some evidence of reliability for SCI. Further evaluation needed (see Krause et al.65 for further details) | 8 items about type of support received from families, friends, & community are ranked on a 7-point scale ranging from 1 (never) to 7 (always). The frequency with which upsetting things happen between the respondents and members of their family, their friends, or their community is also recorded. Scoring NR |

∼10–15 m | +Anson et al. 1993 | |||

| S | Satisfaction With Life Scale (SWLS) | X | Reliability and validity established for SCI (see Diener et at.65 for further details) | 5 items rated on a scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). Items are summed to obtain a score ranging from 5 to 35, with higher scores corresponding to greater life satisfaction. |

∼5 m | -Brillhart 2004 +Cameron et al. 2011 -Hicken et al. 2001 |

||||

| S | Spinal Cord Injury-Quality of Life (SCI-QOL) Bladder Management Difficulties | X | Reliability and validity established for SCI (see Tulsky et al.42 for further details) | 15 items assess bladder management difficulties ‘lately’ are given a score between 1 (never/not at all) and 5 (always/very much). 1 item is reverse scored between 1 (always) & 5 (never) Items are summed then converted to a standardized T-metric score with a mean (SD) = 50 (10). Higher scores indicate higher degree of difficulty. |

NR (est < 10 m) | NR Tulsky et al. 2015 | ||||

| S | Spinal Cord Injury-Quality of Life (SCI-QOL) Bladder Management Difficulties- Short Form | X | Reliability and validity established for SCI (see Tulsky et al.42 for further details) | 8 of the most informative items from the SCI-QOL Bladder Management Difficulties Scale were selected. Items are scored between 1 (never/not at all) & 5 (always/very much). Items are summed then converted to a standardized T-metric score with a mean (SD) = 50 (10). Higher scores indicate higher degree of difficulty. |

NR (est ∼ 5 m) | NR Tulsky et al. 2015 | ||||

| S | WHOQOL-BREF (26 item) | X | X | Reliability and validity established for SCI (see Jang et al.70 for further details) | 26 items are rated on a 5-point scale ranging from 1 to 5. 24 items comprise 4 domains: physical health, psychological health, social relationship, & environment. Mean domain scores (raw scores) are calculated using standardized equations. Domain scores are transformed to a score between 0 (lower QoL) to 100 (higher QoL). 2 items are scored individually. |

∼ 10–15 m | +Luo et al. 2012 | |||

A = Objective Evaluation

B = Societal Standards

C = Achievements

D = Individual Expectations and Priorities

E = Subjective Evaluations and Reactions

O = Objective Measure

S = Subjective Measure

QoL = Quality of Life

SCI = Spinal Cord Injury/Disease

NR = Not reported

+ = significant effect (sensitive to impact/influence)

- = non-significant effect (not sensitive to impact/influence).

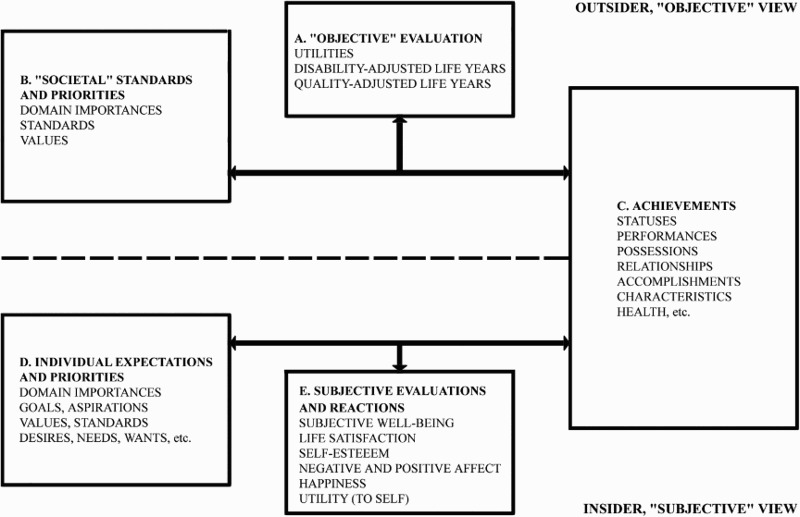

A detailed explanation of the application of Dijkers’ model as a theoretical roadmap for classifying QoL outcomes in SCI has been previously published.6 In brief, QoL outcomes can be subjective or objective in nature.4 The three main concepts comprising QoL are ‘Utility’, ‘Achievements’, and ‘Subjective Well-Being’ (Fig. 1). Each concept is comprised by the interrelation of two or more constructs (i.e. A. Objective evaluation; B. Societal standards and priorities; C. Achievements; D. Individual expectations and priorities; E. Subjective evaluations and reactions). The conceptualization of ‘Utility’, ‘Achievements’, and ‘Subjective Well-Being’ according to the interrelations of each construct, as well as the application of Dijkers’ model for classifying of outcome tools has been documented.6 We used the methodology outlined by our group, to classify QoL outcomes specific to neurogenic bladder as objective or subjective, and have identified the relevant constructs of QoL (i.e. A, B, C, D, E) that comprise each tool.6 The psychometric properties and sensitivity of each tool to capture the impact on QoL were also summarized (Table 2).

Figure 1.

Dijkers’ theoretical framework for the classification of quality of life outcome tools (Reprinted from the Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation 84(4 Suppl), Dijkers MP.), Individualization in quality of life measurement: Instruments and approaches. S-3-14, 2003 with permission from Elsevier).

Results

The initial search identified 368 studies. Following duplicate removal and screening of titles and abstracts, 118 full-text articles were assessed for eligibility and 42 met the inclusion criteria (Fig. 2). Table 1 describes the details of three randomized-controlled trials,19,23,45 13 quasi-experimental studies (12 pre-post1,24,26,28,29,40,41,43,44,47,48,50, 1 time-series25), 3 longitudinal studies,12,21,31, 4 retrospective designs,15,27,39,51 16 cross-sectional studies,13,14,16–18,20,30,32–36,38,46,49,52 1 combined cross-sectional and longitudinal study37, 1 case-control study,22 and 1 mixed qualitative and cross-sectional study.42

Figure 2.

PRISMA flow diagram illustrating the search and selection of studies.

A total of 24 QoL outcome tools were identified (ten objective, fourteen subjective) (Table 2). Seven unstandardized study-specific questionnaires or visual analog scales (VAS) were also identified, and one study reported a global change rating of QoL.

Objective QoL outcomes specific to neurogenic bladder

The Medical Outcomes Short Form-36 (SF-36) was the most commonly used outcome to assess HRQoL.12–20 The SF-12, a shortened version of the SF-36, was also used in two studies.21,22 Both the SF-36 and SF-12 are generic measures of health status (boxes B and C, Fig. 1) that provide information about general physical and mental health components, but the SF-36 provides an additional level of information about eight health domains (i.e. physical functioning, role limitations due to physical health problems, bodily pain, general health, vitality, social functioning, role limitations due to emotional problems, and mental health). Although both outcome tools have acceptable psychometric properties, neither the SF-36 nor the SF-12 is SCI specific, nor do they have items specific to neurogenic bladder.53,54

Despite the lack of specificity to SCI or neurogenic bladder, better bladder function has been found to be associated with higher SF-36 and SF-12 scores.13–16,19,21 For example, after sacral neuromodulation, all subjects with SCI retrospectively reported improved mental and general health, while patients who previously experienced both bladder and bowel incontinence also reported improved role-emotional and social functioning.15 Moderate statistically significant correlations were found between the SF-36 and other HRQoL outcomes related to urinary incontinence.14,19,21 Individuals without bladder incontinence reported higher scores (statistically significant) on the SF-36 domains of general health, physical functioning, role-physical and role-emotional.13,16

There were some discrepancies in associations between bladder function and QoL. In two studies, patients who voided normally had significantly higher physical and mental health compared to those who used other bladder management techniques.12,14 However, significant associations between bladder function and QoL were only reported for the physical health domain in three other studies.17,18,22

The Urogenital Distress Inventory short form (UDI-6) was used to assess patients’ perceptions of neurogenic bladder in four studies (boxes B and C, Fig. 1).23–26 After treatment with various botulinum toxin A (BoNT-A) injections, patients in all four studies showed improvements in bladder function. Statistically significant improvements in UDI-6 scores (P < 0.01) were observed in three of four studies.23–25 The UDI-6 was developed to assess the impact of urinary incontinence on HRQoL; however, item development was not specific to SCI.55 Although the psychometric properties of the UDI-6 have not been fully documented in SCI populations, improvements in UDI-6 scores were reported with improved bladder function, suggesting some degree of validity.

The International Consultation on Incontinence Modular Questionnaire (ICIQ) also assesses the impact of urinary incontinence on QoL (boxes B and C, Fig. 1),56 and was used in three studies.27–29 In two pre-post trials, interventions that included BoNT-A injections positively influenced bladder outcomes (e.g. incontinence, overactive bladder) and significantly improved ICIQ scores (P < 0.001).28,29 In a retrospective study, Böthing et al. reported there were no statistically significant differences in QoL between two types of bladder management (indwelling catheter versus intermittent self-catheterisation).27

The Craig Handicap Assessment and Reporting Technique (CHART), a measure of community integration and social participation was used in two studies.12,22 Specifically, the CHART evaluates limitations in participation in community life in five domains (i.e. Physical independence, Mobility, Occupation, Social integration, and Economic self-sufficiency) (boxes B and C, Fig. 1). The CHART has been validated in SCI populations.57 Four types of bladder management (i.e. indwelling catheters, spontaneous voiding, condom catheterization, and intermittent catheterization) were examined in a longitudinal study. Method of bladder management had a significant influence on ‘Physical independence’, ‘Mobility’, and ‘Occupation’ subscales, with individuals with indwelling catheters reporting significantly lower scores (P < 0.01).12 Bladder management dependence was also significantly associated with greater limitations in participation, specifically on the physical independence, mobility, and occupational functioning subscales (P < 0.05).22 However, it should be noted that this study did not include the ‘Social integration’ or ‘Economic self-sufficiency’ subscales in their analyses.22

Five additional objective QoL outcome tools were identified, neither of which has been validated for SCI. The Health Utility Index (HUI 3) (boxes A, B and C, Fig. 1), a measure of health utility,58 was higher in individuals with no or mild bladder complications compared to those with moderate to severe complications.30 Weilink et al. used the Nottingham Health Profile59 and the Karnofsky Performance Scale60 Index to evaluate QoL after corrective bladder procedures and observed no significant changes in either measure.31 The King's Health Questionnaire (KHQ)61 (boxes B and C, Fig. 1) had associations with bladder function and QoL. For example, patients who reported normal voiding had significantly lower KHQ scores for physical limitation, emotions,14,32 personal relationships,14 incontinence, role limitations, social limitations, and symptom severity32 compared to those who had indwelling catheters or who were dependent on others for intermittent catheterization. Finally, the Sarno Functional Life Scale62 (boxes B and C, Fig. 1) was used in one study, which reported that individuals with a urinary tract infection were significantly less likely to participate in outdoor activities. However, the scale itself lacks psychometric properties for SCI and the authors only used the outdoor activities subscale.33

Subjective QoL outcomes specific to neurogenic bladder

The Qualiveen, a 30-item subjective questionnaire comprising four subscales (i.e. limitations; constraints, fears, and feelings) that was developed specifically for neurogenic bladder in SCI (boxes C and E, Fig. 1), was among the most frequently used subjective outcome tool (n=5).16,21,34–36 With statistically significant correlations between degree of neurogenic bladder and QoL in each of the four subscales, the Qualiveen-30 has acceptable construct and clinical validity. For example, individuals who were dissatisfied with urination method and who experienced longer urination times had higher Qualiveen-30 scores (i.e. lower QoL) than those who were satisfied with their urination (P = 0.0001) or who took less time to urinate (P < 0.05).34 Pearson correlations were also in agreement with the predicted magnitude and direction of relationships with the SF-12 (r = 0.31 to 0.45 PCS and r = 0.28 to 0.45 MCS) and global change ratings of HRQoL (r = 0.48 to 0.56).21 The Qualiveen-30 had good internal consistency (Cronbach's α > 0.80) and high test-retest reliability (ICC total score = 0.90) in English and Italian.21,34 Individuals who were expected to improve showed significantly higher Qualiveen-30 scores (P < 0.001), and the Minimally Important Difference (MID) was established (MID = 0.34 to 0.47) showing responsiveness of the tool.21

Three cross-sectional studies showed significant associations between improved bladder function and Qualiveen-30 scores.16,35,36 Successful implantation of a bladder stimulator was associated with improved bladder function and lower Qualiveen-30 scores (P < 0.001).16,36 Patients who had successful bladder management treatments that resulted in continence had lower scores on the Qualiveen-30 subscales for fear (P = 0.006) and feelings (P = 0.009). When controlled for depression, individuals who were not continent had higher Qualiveen-30 scores for ‘Constraints’ (P = 0.04), ‘Fears’ (P = 0.001), and ‘Feelings’ (P = 0.02).35 Successful implantation of a bladder stimulator was also associated with lower infection rates and improved social life.36

The Quality of Life Index for SCI (QLI-SCI), a measure of satisfaction in and the importance of five domains (‘Health and functioning’, ‘Socioeconomic status’, ‘Psychological and spiritual well-being’, and ‘Family relationships’) (boxes C, D and E, Fig. 1) was also used in five studies.37–41 There is support for internal consistency of items, but evidence of validity in SCI is limited and responsiveness has not yet been established.63 In three pre-post intervention trials, improvements in bladder function after BoNT-A injections lead to significant increases in QLI-SCI scores (P < 0.05).39–41 The number of urinary tract infections was associated with QLI-SCI scores in one longitudinal study,37 but correlations between method of bladder management and QLI-SCI scores were not statistically significant in a pre-post study.38

The Bladder Complications Scale (box E, Fig. 1), the Spinal Cord Injury-Quality of Life (SCI-QoL) Bladder Management Difficulties, and the SCI-QoL Bladder Management Difficulties Short-Form (box E, Fig. 1) were also developed specifically to assess QoL related to neurogenic bladder in SCI. Although all three tools have documented internal consistency, reliability and validity, neither tool has been applied to assess QoL outside of the development studies.42

Although not developed specifically for SCI, there is some evidence of the psychometric properties in SCI for the Incontinence Quality of Life Scale (I-QoL), the Reciprocal Social Support Scale (RSS) and the Satisfaction With Life Scale (SWLS). The I-QoL measures the impact of urinary incontinence on QoL and was used in SCI populations by four studies.19,43–45 High internal consistency, construct validity and responsiveness of the I-QoL have been documented.19 Within-subjects improvements in experimental and pre-post designs showed that participants who received BoNT-A injections to had significant improvements in bladder function and in I-QoL scores (P < 0.05).43–45 Anson et al. used the RSS (boxes C and E, Fig. 1) to measure the amount of support given to and received from family members, friends, and the community in four areas (i.e. social interaction, material assistance, emotional support, and non-paid personal assistance).37 The RSS has acceptable internal consistency for assessing QoL in SCI, but the validity is not clear.64 A significant correlation was reported between frequency of incontinence and material support given and received in one study, but there is no evidence of the impact of bladder function on emotional support given or received.37 The SWLS, a global judgement of life satisfaction (box E, Fig. 1), was used by three studies.12,22,38 Internal consistency and validity have been documented in SCI, but the sensitivity of the SWLS to assess the impact of neurogenic bladder on QoL is unclear.65 One study reported significant differences in SWLS scores between patients with indwelling catheter and those who voided,12 while no differences were observed in SWLS scores and bladder management method in the other two studies.22,38

Additional outcome tools that have shown sensitivity for detecting change in QoL related to neurogenic bladder in SCI include the Affect Balance Scale (ABS), Incontinence Impact Questionnaire (IIQ-7), International Prostate Symptom Score-QoL index (IPSS-QoL), Patient Perception of Bladder Condition (PPBC), and World Health Organization QoL (WHOQOL-BREF). However, none of these outcome tools have evidence of psychometric properties in SCI. The ABS, also known as the Bradburn Scale of Psychological Well-being, assesses social psychological well-being through the difference of positive and negative affect scores (box E, Fig. 1).66 Although Weilink et al. showed significant improvements in ABS scores after implantation of a bladder stimulator, the psychometric properties have not been documented for SCI.32 The IIQ-7 (boxes C and E, Fig. 1) assesses the impact of urinary incontinence on QoL and was developed for the general population.67 Three studies reported that BoNT-A injections treatments improved bladder outcomes and significantly improved IIQ-7 scores (P < 0.05).24–26 The IPSS-QoL has seven items related to urinary symptoms and one item that ranks QoL on a 7-point likert type scale.68 Three studies showed significant within-subject improvements (P < 0.05) in IPSS-QoL scores after BoNT-A injections.23–25 The PPBC is a single-item global measure to assess perceived urinary problems (box C, Fig. 1).69 Kuo et al. used the PPBC to assess patient satisfaction with treatment outcomes. All patients who experienced improved incontinence after BoNT-A injections also reported improvement in PPBC scores.25 Finally, the WHOQOL-BREF (boxes C and E, Fig. 1), validated as a general measure of QoL in SCI populations,70 has displayed significant associations with bladder function. For example, bladder management techniques were significantly associated with WHOQOL-BREF scores, such that patients who reported normal voiding demonstrated the highest QoL scores related to physical health, psychological health, and social relationships (P < 0.05).46

Noonan et al. also used two single items to assess QoL, neither of which was validated for SCI.17 The QoL question from the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer (boxes C and E; Fig. 1) was used to obtain an overall rating of QoL during the past week on a scale ranging from 1 (very poor) to 7 (excellent).71 Level of satisfaction of living with current symptoms was rated on a scale from 1 (very dissatisfied) to 5 (very satisfied).72 Neurogenic bladder was significantly associated with QoL and satisfaction, but only when personal and confounding factors were not controlled for.17

Seven studies used unstandardized study-specific QoL outcomes. Four studies showed improvements in QoL related to neurogenic bladder using VAS (boxes C and E, Fig. 1); however, the VAS were not validated for SCI. Vaidyananthan et al. rated QoL on a scale from 0 (extremely miserable) to 100 (highly pleased when able to pursue the following activities: 1) go on holidays, (2) socialize with friends, (3) go shopping, (4) visit friend's homes, (5) receive guests in home, or (6) pursue studies or vocation. QoL improved during the treatment regime with intermittent catheterization and bladder instillation of oxybutynin.47 Taweel et al. rated QoL on a scale ranging from 0 (lower QoL) to 10 (higher QoL) and reported significant, mean 3-point improvement in QoL after BoNT-A injections treatment.1 On a scale ranging from 1 (extremely unsatisfied) to 10 (extremely satisfied), 67% of the sample reported a score of 8 or more after urinary tract reconstruction.48 Walsh et al. developed a survey to quantify the improvement in continence related to daily living in six areas (continence, body image, independence, convenience, time saving, and satisfaction) that were rated using VAS. The VAS scale or scoring is not reported; therefore, is difficult to interpret the results and sensitivity of the outcome for neurogenic bladder.49 Similarly, Moreno et al. used a study specific questionnaire, but the details of the evaluation were not documented this limiting our ability to understand how QoL was assessed.50

Three studies reported statistical associations between study-specific QoL questionnaires and bladder function after corrective procedures. Bladder reconstruction was associated with improved QoL in various domains, including dependence, performance of daily activities, socialization, sense of control, participation in vocational and leisure activities, and overall QoL.48,51,52 In one study, the reasons for improvement included, no longer requiring urinary bags, having more freedom, independence, dry between catheterizations, and improved body image.48

Finally, one study used a global change rating of QoL, where patients reported whether they had experienced any change in limitations, frequency of limitations, fears, and feelings related to their urinary problems since their previous clinic visit.21 This 15-point scale ranging from −7 (a very great deal worse) to 0 (no change) to +7 (a very great deal better) was validated for multiple sclerosis.73 There were statistically significant moderate to strong associations between change in Qualiveen-30 and global change rating (r = 0.48 to 0.56; P < 0.05).21

Discussion

The purpose of this systematic review was to summarize and classify existing outcome tools that assess the influence of neurogenic bladder on QoL (and related constructs) in individuals with SCI. This review shows that existing outcomes measures are representative of the three major domains of QoL as defined by Dijkers,4,8 including QoL as ‘Achievements’, ‘Utility’, and ‘Subjective well-being’. Many objective tools are sensitive to neurogenic bladder, but four have psychometric evidence for SCI (CHART, HUI 3; SF-36/SF-12). Many subjective tools also show sensitivity to neurogenic bladder and eight have psychometric evidence for SCI (Bladder Complications Scale, I-QoL, QLI-SCI, Qualiveen, RSS, SWLS, SCI-QOL/SCI-QOL-ShortForm). Four subjective tools were developed specifically for SCI (QLI-SCI, Qualiveen, Bladder Complications Scale, SCI-QOL), two of which were sensitive to neurogenic bladder (QLI-SCI, Qualiveen). It is not our intention to endorse one QoL outcome tool over another. Instead, the goal is that the classification of existing outcomes tools in this review may assist researchers and clinicians in the outcome tool selection process.

Consideration of both objective and subjective outcomes are important in SCI. Objective measures capture information that is deemed important by society, but does not consider subjective information that is perceived to be important by the individual. Although subjective outcomes are often criticized for ignoring societal norms, objective outcomes may disregard an individuals’ feeling about an important issue.74 Therefore, a combination of complimentary tools that include the three QoL domains (i.e. both objective and subjective tools), sensitivity to neurogenic bladder, and validated psychometric properties for SCI should be used to capture a comprehensive assessment of QoL. Study-specific questionnaires may be useful when there are no appropriate measures available that assess the construct of interest but should be paired with an existing QoL measure. Since numerous validated outcome tools have been identified for evaluating QoL related to neurogenic bladder in SCI, it is recommended that existing QoL measures be used and further validated over conception of new study-specific tools.

The Qualiveen-30 and QLI-SCI, both subjective measures, have documented evidence of sensitivity to neurogenic bladder and sound psychometric properties. In a recent systematic review on QoL outcomes related to neurogenic bladder and bowel in heterogeneous populations, the Qualiveen was identified as a condition-specific QoL outcome tool worthy of further validation to assess reliability and validity in heterogeneous populations, precision of the language, and capability of measuring change longitudinally in response to treatments or bladder management strategies.75 From a clinical perspective, one of the strengths of the Qualiveen-30 is that it was developed with input from individuals with SCI. The Qualiveen reflects ‘Achievements’ (box C in Fig. 1) and ‘Subjective evaluations and reactions’ (box E in Fig. 1). Thus it provides a comprehensive evaluation of perceived accomplishments in various life areas (e.g. employment, social relations, community participation, etc.) and individuals’ perception of life satisfaction.8 Since the Qualiveen is lacking assessment of ‘Individual expectations’ (box D in Fig. 1), information about expected versus actual status (i.e. QoL as ‘Subjective wellbeing’) cannot be fully interpreted. The QLI-SCI measures ‘Achievements’ (box C in Fig. 1), ‘Individual expectations’ (box D in Fig. 1), and ‘Subjective evaluations and reactions’ (box E in Fig. 1); therefore provides a more comprehensive evaluation of satisfaction and important in various life domains. Although it takes only 10 minutes to administer, further validation of this tool is required to establish responsiveness. The Qualiveen has been recommended for use internationally,34,76 but the clinical burden of administering the Qualiveen-30 is high (approximately 30 minutes to complete). An eight-item Qualiveen Short Form (SF-Qualiveen) takes only a few minutes to administer and is highly correlated with the Qualiveen-30, but it has only been validated for use in multiple sclerosis.77 Further evaluation of the QLI-SCI and SF-Qualiveen is warranted in SCI populations.

Tulsky et al. used a patient-centered, modern measurement theory derived approach to develop three subjective QoL outcome measures about neurogenic bladder in SCI.42 From a clinical and statistical perspective, the Spinal Cord Injury-Quality of Life (SCI-QOL) Bladder Management Difficulties, the SCI-QOL Bladder Management Difficulties-Short Form and the Bladder Complications Scale show promise for measuring ‘Subjective evaluations and reactions’ (box E in Fig. 1). Therefore, these tools provide information about perceived life-satisfaction, but not about achievements or expectations. The development of these SCI-specific tools is timely in the advancement of SCI treatment and interventions related to neurogenic bladder, but further application in evaluative study designs is required to establish sensitivity to neurogenic bladder before recommending these tools for research and practice.

Of the 10 objective measures of QoL identified, the SF-36 was the most frequently used (n = 9). Similar findings were reported in a review of outcomes to assess QoL related to neurogenic bladder and bowel in a heterogeneous sample of patients with neurological issues.75 The SF-36 provides a reasonably valid assessment of QoL from an outsider's perspective; however, generic measures of HRQoL may lack sensitivity to the unique aspects specific to SCI.78 Although it can be administered in less than 10 minutes, and has shown sensitivity to change in SCI, evidence of psychometric properties in SCI is limited and there are no domains specific to neurogenic bladder. Therefore, as noted by Patel et al., QoL and satisfaction with neurogenic bladder management strategies may be overlooked.75 Further, there is controversy associated with the SF-36. There are wheelchair users who have reported that there are offensive items on the SF-36 since there are several items refer to climbing or walking.54,79 Further, persons with disabilities view the underlying assumptions of the SF-36 (and other health-related QoL measures) as being flawed since having a disability does not necessarily equate with poor QoL.79,80 These limitations could be minimized by using a condition-specific tool with the SF-3679 or use the SF-36 V2, which has addressed some of the issues with the items of the original SF-36. However, it should be noted that the SF-36 V2 has not been fully validated for the SCI population,81 nor has it been used to assess the influence of neurogenic bladder on QoL post-SCI.

The CHART has been validated for use in SCI and has documented sensitivity to neurogenic bladder, but similar to the SF-36, it is a generic measure of HRQoL that is not specific to SCI.57 Therefore, it may be useful to combine the SF-36 or the CHART with other QoL outcomes that are specific to neurogenic bladder and SCI. For example, the UDI-6 represents an objective outcome tool that is specific to neurogenic bladder and evaluates objective QoL as ‘Societal standards and priorities’ (box B in Fig. 1). The UDI-6 has shown sensitivity to neurogenic bladder, but the psychometric properties have yet to be validated in SCI.23–25 Additionally, health utility (i.e. an objective evaluation of preference-based health state), is becoming of increasing importance for evaluating cost-effectiveness of treatments and rehabilitation interventions. Only one study measured QoL as ‘Utility’ (boxes A, B and C in Fig. 1) using the Health Utility Index (HUI 3).30 In this study, Craven et al. documented statistically significant associations between QoL and neurogenic bladder. However, the HUI 3 has only some preliminary concurrent validity for its use in persons with SCI,58 and further work is needed to validate it for this population.

Additional subjective and objective tools have been summarized (Table 2), but caution is suggested for application in research and practice. For example, the IPSS, a subjective outcome, is used widely to assess lower urinary tract symptoms in men before and after treatment. However, the IPSS does not evaluate all lower urinary tract symptoms (e.g. incontinence and pain), and is relatively complicated for use in some populations.82,83 Similarly, the Sarno Functional Life Scale, an objective QoL tool, is difficult to interpret and is burdensome to complete.62 Furthermore, tools such as the single-item PPBC may not capture the depth or breadth of the impact of bladder function on quality of life, but it may serve as a quick assessment of the patient's perception of symptoms, treatments, and side effects that could help to initiate conversation about neurogenic bladder and QoL.84

Study limitations

One limitation of this review is that samples with <50% of individuals with SCI were excluded, which may inflict bias in the results. For example, the Neurogenic Bladder Symptom Score measures urinary symptoms and consequences in patients with acquired or congenital neurogenic bladder, but this tool was not included in this review because the initial validation study included a sample with 35% SCI.85 Given our aim to create a SCI-specific tool-kit, it was decided that tools that have been used in samples with <50% of SCI individuals would not be reflective nor generalizable to SCI populations.

Additionally, bladder management strategies largely influences QoL, such successful bladder management methods lead to higher quality of life. Although this is very important for determining successful interventions for improving QoL, we did not consider how various bladder management approaches might affect individual study outcomes. While we realize this may limit the practical application of our findings, the purpose of the review is to provide a roadmap for the selection of outcome tools (i.e. not for choosing interventions).

Interpretations and suggestions for outcome tool selection may be limited as they are based mainly on findings from cross-sectional designs, thus limiting the ability to establish the direction of the relationship between QoL and neurogenic bladder. For example, the study by Craven et al. was the only study to document significant associations between neurogenic bladder and health utility.30 However, causality between neurogenic bladder and QoL cannot be established without controlled experimental trials. Further, we have not broken down the studies to specify which aspect of neurogenic bladder is evaluated by each of the tools (e.g. incontinence, detrusor pressure, recurrent infection, renal impairment). This is particularly cogent as individuals often rank incontinence as most distressing, while the health system may perceive recurrent infection or renal impairment as issues of greater importance.

Despite some QoL tools not being employed in experimental trials, 14 studies did use experimental or quasi-experimental designs to provide evidence for the direction of the relationship between QoL and neurogenic bladder. Therefore, conclusions of this review and recommendations are based on high-quality evidence. More research studies that examine associations between QoL and changes in neurogenic bladder over time would clarify whether QoL changes in persons with SCI as bladder function improves.

Conclusion

Although several objective and subjective tools have been used to assess the influence of neurogenic bladder on QoL in SCI, the QLI-SCI and Qualiveen are the only validated condition-specific outcomes that have shown consistent sensitivity to neurogenic bladder. The Spinal Cord Injury-Quality of Life (SCI-QOL) Bladder Management Difficulties and the Bladder Complications Scale represent promising new subjective QoL tools, but further confirmation of sensitivity to neurogenic bladder is required. None of the objective tools were specific to neurogenic bladder or SCI. However, the SF-36 provides a valid assessment of objective QoL in SCI. Further work is also required to validate SCI objective QoL measures, which could be useful for informing policy and practices related to resource allocation for bladder care post-SCI.

Disclaimer statements

Contributors None.

Conflicts of interest Material in this manuscript has been presented in part at the International Spinal Cord Society and American Spinal Injury Association Joint Conference in Montreal, QC from May 14–16, 2015. We certify that no party having a direct interest in the results of the research supporting this article has or will confer a benefit on us or on any organization with which we are associated AND, we certify that all financial and material support for this research (e.g. NIH or NHS grants) and work are clearly identified in the title page of the manuscript. The manuscript submitted does not contain information about medical device(s).

Ethics approval None.

Funding Statement

The project was supported by the Paralyzed Veterans of America, the Ontario Neurotrauma Foundation, and the Réseau provincial de recherche en adaptation-réadaptation (REPAR); Grant numbers PVA 735; 2010-KM-SCI-QOL-825; 2008-ONF-REPAR-601; 2007-ONF-REPAR-518).

References

- 1.Taweel WA, Seyam R.. Neurogenic bladder in spinal cord injury patients. Res Rep Urol 2015;7:85–99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ku JH. The management of neurogenic bladder and quality of life in spinal cord injury. BJU Int 2006;98(4):739–45. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2006.06395.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Menon EB, Tan ES.. Bladder training in patients with spinal cord injury. Urology 1992;40(5):425–9. doi: 10.1016/0090-4295(92)90456-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dijkers M. “What's in a name?” The indiscriminate use of the “Quality of life” label, and the need to bring about clarity in conceptualizations. Int J Nurs Stud 2007;44(1):153–5. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2006.07.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Post MW, de Witte LP, Schrijvers AJ.. Quality of life and the ICIDH: towards an integrated conceptual model for rehabilitation outcomes research. Clin Rehabil 1999;13(1):5–15. doi: 10.1191/026921599701532072 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hitzig SL, Balioussis C, Nussbaum E, McGillivray CF, Craven BC, Noreau L.. Identifying and classifying quality-of-life tools for assessing pressure ulcers after spinal cord injury. J Spinal Cord Med 2013;36(6):600–15. doi: 10.1179/2045772313Y.0000000129 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Emery MP, Perrier L, Acquadro C.. Patient-Reported Outcome and Quality of Life Instruments Database (PROQOLID): frequently asked questions. Health Qual Life Outcome 2005;8(3):12. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-3-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dijkers MP. Quality of life of individuals with spinal cord injury: a review of conceptualization, measurement, and research findings. J Rehabil Res Dev 2005;42(3 Suppl 1):87–110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Browne JP, O'Boyle CA, McGee HM, McDonald NJ, Joyce CR.. Development of a direct weighting procedure for quality of life domains. Qual Life Res 1997;6(4):301–9. doi: 10.1023/A:1018423124390 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Moons P, Budts W, De Geest S.. Critique on the conceptualisation of quality of life: a review and evaluation of different conceptual approaches. Int J Nurs Stud 2006;43(7):891–901. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2006.03.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Balioussis C, Hitzig SL, Flett H, Noreau L, Craven CB.. Identifying and classifying quality of life tools for assessing spasticity after spinal cord injury. Top Spinal Cord Inj Rehabil 2014;20(3):208–24. doi: 10.1310/sci2003-208 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cameron AP, Wallner LP, Forchheimer MB, Clemens JQ, Dunn RL, Rodriguez G, et al. Medical and psychosocial complications associated with method of bladder management after traumatic spinal cord injury. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2011;92(3):449–56. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2010.06.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gurcay E, Bal A, Eksioglu E, Cakci A.. Quality of life in patients with spinal cord injury. Int J Rehabil Res 2010;33(4):356–8. doi: 10.1097/MRR.0b013e328338b034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Liu CW, Attar KH, Gall A, Shah J, Craggs M.. The relationship between bladder management and health-related quality of life in patients with spinal cord injury in the UK. Spinal Cord 2010;48(4):319–24. doi: 10.1038/sc.2009.132 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lombardi G, Nelli F, Mencarini M, Del Popolo G.. Clinical concomitant benefits on pelvic floor dysfunctions after sacral neuromodulation in patients with incomplete spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord 2011;49(5):629–36. doi: 10.1038/sc.2010.176 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Martens FM, den Hollander PP, Snoek GJ, Koldewijn EL, van Kerrebroeck PE, Heesakkers JP.. Quality of life in complete spinal cord injury patients with a Brindley Bladder Stimulator compared to a matched control group. Neurourol Urodyn 2011;30(4):551–5. doi: 10.1002/nau.21012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Noonan VK, Kopec JA, Zhang H, Dvorak MF.. Impact of associated conditions resulting from spinal cord injury on health status and quality of life in people with traumatic central cord syndrome. Arch Physical Med Rehabil 2008;89(6):1074–82. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2007.10.041 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Oh SJ, Ku JH, Jeon HG, Shin HI, Paik NJ, Yoo T.. Health-related quality of life of patients using clean intermittent catherization for neurogenic bladder secondary to spinal cord injury. Urology 2005;65(2):306–10. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2004.09.032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schurch B, Denys P, Kozma CM, Reese PR, Slaton T, Barron R.. Reliability and validity of the Incontinence Quality of Life questionnaire in patients with neurogenic urinary incontinence. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2007;88(5):646–52. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2007.02.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Westgren N, Levi R.. Quality of life and traumatic spinal cord injury. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 1998;79(11):1433–9. doi: 10.1016/S0003-9993(98)90240-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bonniaud V, Bryant D, Pilati C, Menarini M, Lamartina M, Guyatt G, et al. Italian Version of Qualiveen-30: cultural adaptation of a neurogenic urinary disorder-specific instrument. Neurourol Urodyn 2011;30(3):354–9. doi: 10.1002/nau.20967 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hicken BL, Putzke JD, Richards JS.. Bladder management and quality of life after spinal cord injury. Am J Phys Med Rehabil 2001;80(12):916–22. doi: 10.1097/00002060-200112000-00008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chen YC, Kuo HC.. The therapeutic effects of repeated detrusor injections between 200 or 300 units of OnabotulinumtoxinA in chronic spinal cord injured patients. Neurourol Urodyn 2014;33(1):129–34. doi: 10.1002/nau.22395 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chen YC, Liao CH, Kuo HC.. Therapeutic effects of detrusor botulinum toxin A injection on neurogenic detrusor overactivity in patients with different levels of spinal cord injury and types of detrusor sphincter dyssynergia. Spinal Cord 2011;49(5):659–64. doi: 10.1038/sc.2010.179 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]