Abstract

Rationale:

Despite a vaccine being widely available, measles continues to occur frequently, with sometimes lethal consequences.

Patients concerns:

The mortality rate reaches 35% and measles represents 44% of the 1.4 million deaths which are due to preventable diseases. Severe forms of measles are reported, mainly in young, unvaccinated adults, and in specific populations. The risk factors for severe measles include no or incomplete vaccination and vitamin A deficiency. Apart from secondary measles-related infections, severe measles is mainly represented by neurological, respiratory, and digestive symptoms.

Diagnoses:

Strengthening the hypothesis that there is a link between vitamin A deficiency and severe measles in this paper we report the case of a 25-year-old unvaccinated man hospitalized for severe and complicated measles.

Outcomes:

The evolution was good after administration of intramuscular vitamin A as well as intravenous ribavirin.

Lessons:

Measles remains a fatal and serious disease. The early use of ribavirin and vitamin A shows significant improvements regarding morbimortality and should be systematic in severe cases.

Keywords: ribavirin, severe measles, vaccine, vitamin A deficiency, vitamin A therapy

1. Introduction

Despite a vaccine available preventing this disease, severe forms of measles (including neurological and respiratory involvement) are reported, mainly in unvaccinated young adults. Among the main risk factors for severe measles the vitamin A deficiency has been already described. Here, we report the case of a 25-year-old unvaccinated man hospitalized for severe and complicated measles. We then discuss comprehensively both preventive and therapeutic management of severe measles.

2. Case report

A 25-year-old Romanian man, from the Roma community and who had been living in France for 2 months at the time of presentation, was admitted to our hospital in Marseille, France, for fever, diarrhea, and conjunctivitis. He had no history of medical or surgical disease and was not taking any treatment upon admission. He was not a drug user and smoked 5 cigarettes per day. There were no risks of sexually transmitted diseases reported.

At time of admission, clinical examination revealed a fever at 38.5°C, tachycardia at 125 beats per minute, sweat, submandibular centimetric lymphadenopathies, Koplik's spots, bilateral conjunctivitis, erythematous extending facial eruption, and diarrhea without signs of dehydration. His blood pressure was stable at 129/68 mm Hg. Pulmonary auscultation and neurological examination were normal.

Biological analysis showed hyponatremia at 126 mmol/L, hypokalemia at 3.33 mmol/L, mild acute renal insufficiency with elevated creatinine at 100 μmol/L and clearance at 86 mL/min, anicteric cholestasis and cytolysis 3 times higher than normal, and an inflammatory syndrome with C reactive protein at 55 mg/L.

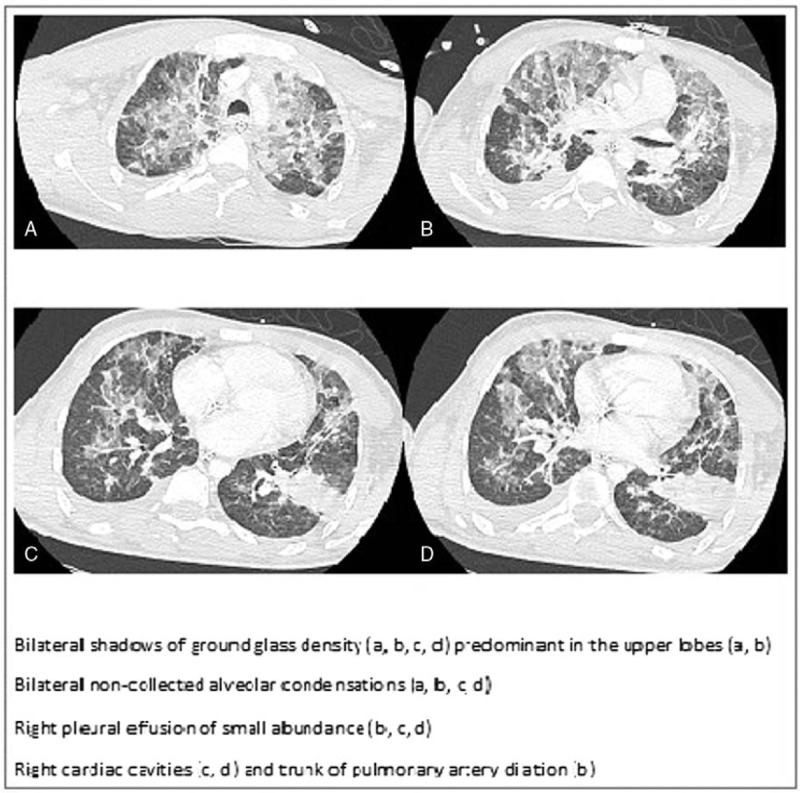

Initially, chest X-rays were normal. At day 2, bilateral pneumonia was clinically diagnosed and confirmed by a thoracic computed-tomography scanner (CT scan) (Fig. 1). Meanwhile, a diagnosis of measles was biologically confirmed with positive immunoglobulin M in serum, and positive polymerase chain reaction (PCR) in urine, pharyngeal sample, and serum.[1]

Figure 1.

Thoracic computed-tomography scanner of bilateral pneumonia due to Staphylococcus aureus and measles.

On the third day after admission, the patient was transferred to the intensive care unit (ICU) for 20 days for multiorgan failure. Neurological failure was multifactorial, due to hyponatremia and acute measles encephalitis with positive PCR for measles in the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) but normal magnetic resonance imaging. Cardiac and respiratory failure was imputed to septic shock and bilateral associated wild type of Staphylococcus aureus and measles-linked pneumonia. Severe hepatic cytolysis, due to fortuitously diagnosed hepatitis B, completed the picture.

Meanwhile, the patient was treated with ophthalmic vitamin A for a corneous ulcer.

Biological findings provided further insights into multiple ionic and vitamin deficiencies. Vitamin deficiencies included hypophosphoremia at 0.62 mmol/L and severe vitamin A deficiency at 0.17 mg/L. These were all supplemented during hospitalization.

Overall, this patient presented measles which was complicated with pneumonia, acute encephalitis, pancreatitis, and a corneous ulcer, associated with vitamin A deficiency. The treatment administered included intravenous ribavirin for 5 days at 1 g per dose 4 times a day, intramuscular vitamin A 200,000 UI per day for 4 days, and ophthalmic vitamin A therapy.

In addition, pneumonia required initial intubation and was treated with the appropriate antistaphylococcal agent. The patient was successfully extubated at day 11 after admission, and evolution showed complete respiratory, neurological, cardiac, renal, ophthalmic and digestive recovery. A vitamin A control revealed normalization at 0.58 mg/L.

The ethics local committee of IHU Méditerranée Infection, Marseille, France has approved this study.

3. Discussion

3.1. Measles complications and severe measles

Secondary infections are to be distinguished from severe measles. The former are due to T cell cytopenia leading to immune suppression and secondary severe infections, particularly in developing countries.[2] Up to 85% of measles’ deaths in South Africa were imputed to a viral or bacterial secondary infection.[3]

Meanwhile, severe measles includes gastrointestinal, pulmonary, neurological, and ophthalmic syndromes. Gastrointestinal symptoms concern mainly of diarrhea (8% of cases), gingivostomatitis, gastroenteritis, hepatitis, mesenteric lymphadenitis, and appendicitis. Measles-related pneumonia is the symptom most associated with death, usually due to secondary infections.[4] However, the measles virus itself leads to bronchopneumonia, laryngotracheobronchitis, bronchiolitis, and bronchiectasis.[3,4] Finally, 3 main measles-associated neurological syndromes have been described, including encephalitis, as is the case in our patient, acute disseminated encephalomyelitis, and subacute sclerosing panencephalitis. Cardiac and ophthalmic symptoms, concerning respectively perimyocarditis and keratitis or corneous ulcers, complete the symptoms of the severe form of measles.[5]

3.2. Moving toward systematic high dose vitamin A treatment

The risk factors for severe measles-related complications include immunocompromised hosts, pregnant women, extreme ages, individuals with poor nutritional status and vitamin A deficiency.[6] The latter increases the risk of complications in children, promotes xerophthalmia, corneal ulcers and blindness, and delays recovery. Acute measles worsens vitamin A deficiency by depleting vitamin A stores and increasing its utilization, leading to more frequent and severe ocular injuries.[4,7,8]

As vitamin A supplementation has shown to lead to a reduction in morbidity and mortality in children under 5 years of age,[9] the World Health Organization recommends intramuscular vitamin A administration for all children as soon as acute measles is diagnosed, followed by a second dose the next day, even in developed countries where measles is usually benign. Doses differ according to the age of the patient, at 50,000 UI/dose for neonates younger than 6 months, 100,000 UI/dose between 6 and 11 months of age, and 200,000 UI/dose for 12-month-old children and older. If clinical signs of vitamin A deficiency are noticed (Bitot's spots), a third dose should be administered 4 to 6 weeks later.[7]

Specific populations such as Gypsy and Czech populations, who have poor nutritional status, are at a high risk of vitamin A, C, and E deficiencies.[10] Subsequently, severe measles-related complications are reported in those populations, enhancing the hypothesis of a link between vitamin A deficiency and severe measles in adults.[11]

Although it remains to be proven, our initially severely vitamin A deficient patient's recovery might have been partially helped by high doses of vitamin A supplementation.

Further studies are needed to establish the value of systematically screening for vitamin A deficiency in adults with acute measles, particularly when they are from a poor background, and the benefits of systematic vitamin A supplementation in those patients.

3.3. Use of ribavirin therapy in severe cases of measles

The reported benefits of ribavirin therapy include decreased duration of symptoms, shorter hospitalization, a reduction in the appearance of measles-related complications and reduced seriousness of severe forms of the symptoms, particularly pneumonia and respiratory distress.[12–14]

Furthermore, a significantly reduced mortality rate was reported in a cross-sectional study in which 100 adult patients diagnosed with acute measles received ribavirin (n = 54) or did not (n = 46). The number of fatal cases reached 4.34% in the group who did not receive ribavirin, compared to 0% in the other group.[12] During measles outbreak in a children's oncology unit, a delay in starting ribavirin was associated with fatal complications (2 of 2 vs 0 of 13, P = .009).[15] Unlike nebulized ribavirin which has no clinical benefits, intravenous or oral ribavirin is reported as being equally efficient in terms of morbimortality.[14]

No consensual recommendations are available concerning the duration of therapy and dosages. One case report used a dose of 50 mg/kg/day for 3 weeks on a 9-year-old child.[16] Our patient received a 5-day course of intravenous ribavirin at doses of 1 g every 6 hours, as reported in the Ortac Ersoy et al[17] case report, with 2 g as a loading dose followed by 1 gram 4 times a day. Faced with the lack of specific guidelines on the treatment of severe measles in adults, it has been impossible to conduct randomized controlled trials on those cases.[17] Given the clinical severity which our patient presented, and following a collegial decision, he received both ribavirin and vitamin A therapy to prevent death or deadly complications.

3.4. Unvaccinated populations, persistence of outbreaks, and measles in vaccinated patients

Worldwide measles vaccination coverage has improved since 2000 but remains insufficient and incomplete in 2015, dropping from 85% for the first dose to 61% for the second dose.[18] This has led to persistent measles outbreaks even in developed countries such as Canada,[19,20] France,[21] the Netherlands,[22] and Spain.[23]

Various profiles of unvaccinated populations have emerged. A significant proportion of unvaccinated cases remain due to the unavailability or lack of health care in sub-Saharan and South-East Asian countries, India, and in marginalized subgroups such as the Roma, who present a measles immunization rate of only 3% in Italy.[23–25] The refusal, in developed countries, to vaccinate, due to the so-called “Wakefield generation” which led to fears of still unproven link between autism and the mumps, measles, and rubella (MMR) vaccine, and a subsequent lack of vaccination.[26] The “antivaxxing” movement, which extols the virtues of nonvaccination, also represents a small but active group which leads to reduced immunization rates.[27] Finally, a more concerning unvaccinated population are healthcare workers, who have been shown to be insufficient protected against measles, accounting for 100% of seventeen cases during an outbreak of nosocomial cases in Italy, and 14% of the 19- to 24-year-old healthcare workers at the University Hospital of Timone in Marseille, France in 2011.[25,28]

Two questions remain unsolved. Firstly, the reason for the occurrence of measles in partially or fully vaccinated populations continues to be unclear.[29] Schaid et al reported an estimated heritability of 13%, compared to an earlier study on twins in the same community, which resulted in a heritability estimate of 88.5%. This finding suggests that there are either many rare genetic variants, or many common genetic variants of small effect sizes which contribute to variations in antibody titers in response to the measles vaccine.[30] Other hypotheses have been supported by Voigt et al,[31] suggesting that there is a probability of a genetically improved humoral and cell-mediated immune response to immunization in patients with African-American ancestry.

The second issue which remains is that of measles vaccination after hospitalization for measles for which laboratory confirmation of measles is sufficient to consider an individual being immune to that particular disease.[4]

4. Conclusion

Measles remains a fatal and serious disease, particularly for adults. A hypothetical link between vitamin A deficiency and severe measles-related complications should raise the question of a systematic screening vitamin A levels in adults diagnosed with acute measles, and/or a systematic supplementation without waiting for biological results. The use of ribavirin on a case-by-case basis, either administered intravenously or orally, shows significant improvements regarding morbimortality. Early administration significantly lowers the number of fatal cases leading to the question of the recommended versus the current empirical use. Finally, further studies are needed to clearly define the cause of measles in fully immunized patients, and to establish recommendations about vaccination after severe measles.

Footnotes

Abbreviations: CSF = cerebrospinal fluid, CT scan = computed-tomography scanner, PCR = polymerase chain reaction.

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- [1].Melenotte C, Cassir N, Tessonnier L, et al. Atypical measles syndrome in adults: still around. BMJ Case Rep 2015;2015:pii: bcr2015211054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Nandy R, Handzel T, Zaneidou M, et al. Case-fatality rate during a measles outbreak in eastern Niger in 2003. Clin Infect Dis 2006;42:322–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Beckford AP, Kaschula RO, Stephen C. Factors associated with fatal cases of measles. A retrospective autopsy study. S Afr Med J 1985;68:858–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Hamborsky J, Kroger A, Wolfe S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Epidemiology and Prevention of Vaccine-Preventable Diseases. 13th ed.Washington, DC: Public Health Foundation; 2015. 209–29. [Google Scholar]

- [5].Cherry JD. Feigin RD, Cherry JD, Demmler-Harrison GJ, et al. Measles Virus. Textbook of Pediatric Infectious Diseases 6th ed.Philadelphia: Saunders; 2009. 2427. [Google Scholar]

- [6].Moss WJ, Griffin DE. Measles. Lancet 2012;379:153–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Perry RT, Halsey NA. The clinical significance of measles: a review. J Infect Dis 2004;189(suppl 1):S4–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].English AI. Measles vaccines: WHO position paper. Relev Epidemiol Hebd 2009;84:349–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Imdad A, Mayo-Wilson E, Herzer K, et al. Vitamin A supplementation for preventing morbidity and mortality in children from six months to five years of age. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2017;3:CD008524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Dejmek J, Ginter E, Solanský I, et al. Vitamin C, E and A levels in maternal and fetal blood for Czech and Gypsy ethnic groups in the Czech Republic. Int J Vitam Nutr Res 2002;72:183–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Melenotte C, Brouqui P, Botelho-Nevers E. Severe measles, vitamin A deficiency, and the Roma community in Europe. Emerg Infect Dis 2012;18:1537–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Pal G. Effects of ribavirin on measles. J Indian Med Assoc 2011;109:666–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Forni AL, Schluger NW, Roberts RB. Severe measles pneumonitis in adults: evaluation of clinical characteristics and therapy with intravenous ribavirin. Clin Infect Dis 1994;19:454–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Barnard DL. Inhibitors of measles virus. Antivir Chem Chemother 2004;15:111–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Roy Moulik N, Kumar A, Jain A, et al. Measles outbreak in a pediatric oncology unit and the role of ribavirin in prevention of complications and containment of the outbreak. Pediatr Blood Cancer 2013;60:E122–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Gururangan S, Stevens RF, Morris DJ. Ribavirin response in measles pneumonia. J Infect 1990;20:219–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Ortac Ersoy E, Tanriover MD, Ocal S, et al. Severe measles pneumonia in adults with respiratory failure: role of ribavirin and high-dose vitamin A. Clin Respir J 2016;10:673–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Patel MK, Gacic-Dobo M, Strebel PM, et al. Progress toward regional measles elimination—Worldwide, 2000–2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2016;65:1228–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Dallaire F, De Serres G, Tremblay F-W, et al. Long-lasting measles outbreak affecting several unrelated networks of unvaccinated persons. J Infect Dis 2009;200:1602–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].De Serres G, Markowski F, Toth E, et al. Largest measles epidemic in North America in a decade–Quebec, Canada, 2011: contribution of susceptibility, serendipity, and superspreading events. J Infect Dis 2013;207:990–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].CNR Rougeole. Measles National Center. Activity report. 2012–2016. 2016. [Google Scholar]

- [22].Woudenberg T, van Binnendijk RS, Sanders EAM, et al. Large measles epidemic in the Netherlands, May 2013 to March 2014: changing epidemiology. Euro Surveill 2017;22:30443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].García Comas L, Ordobás Gavín M, Sanz Moreno JC, et al. Community-wide measles outbreak in the Region of Madrid, Spain, 10 years after the implementation of the Elimination Plan, 2011–2012. Hum Vaccin Immunother 2017;13:1078–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Pojani E, Nelaj E, Ylli A. An insight into the immunization coverage for combined vaccines in Albania. Eur Sci J 2017;13:33–42. [Google Scholar]

- [25].Filia A, Amendola A, Faccini M, et al. Outbreak of a new measles B3 variant in the Roma/Sinti population with transmission in the nosocomial setting, Italy, November 2015 to April. Euro Surveill 2016;21:pii:30235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Ahmed A, Sahota A, Stephenson I, et al. Measles—a tale of two sisters, vaccine failure, and the resurgence of an old foe. J Infect 2017;74:318–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Anti-vaxxing: a privilege of the fortunate. PubMed—NCBI. Available at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/?term=Kamadjeu+R.+et+al.+Anti-vaxxing+%3A+a+privilege+of+the+fortunate.+Lancet+Infect+Dis.+2015%3B15(7)%3A766-7.+doi%3A+10.1016%2FS1473-3099(15)00072-9. Accessed 25 September 2017. [Google Scholar]

- [28].Botelho-Nevers E, Cassir N, Minodier P, et al. Measles among healthcare workers: a potential for nosocomial outbreaks. Euro Surveill 2011;16:pii:19764. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Zhang Z, Zhao Y, Yang L, et al. Measles outbreak among previously immunized adult healthcare workers, China, 2015. Can J Infect Dis Med Microbiol 2016;2016:1742530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Schaid DJ, Haralambieva IH, Larrabee BR, et al. Heritability of vaccine-induced measles neutralizing antibody titers. Vaccine 2017;35:1390–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Voigt EA, Ovsyannikova IG, Haralambieva IH, et al. Genetically defined race, but not sex, is associated with higher humoral and cellular immune responses to measles vaccination. Vaccine 2016;34:4913–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]