Abstract

Liposomal spherical nucleic acids (LSNAs) are an attractive therapeutic platform for gene regulation and immunomodulation due to their biocompatibility, chemically tunable structures, and ability to enter cells rapidly without the need for ancillary transfection agents. Such structures consist of small (<100 nm) liposomal cores functionalized with a dense, highly oriented nucleic acid shell, both of which are key components in facilitating their biological activity. Here, the properties of LSNAs synthesized using conventional methods, anchoring cholesterol terminated oligonucleotides into a liposomal core, are compared to LSNAs made by directly modifying the surface of a liposomal core containing azide-functionalized lipids with dibenzocyclooctyl-terminated oligonucleotides. The surface densities of the oligonucleotides are measured for both types of LSNAs, with the lipid-modified structures having approximately twice the oligonucleotide surface coverage. The stabilities and cellular uptake properties of these structures are also evaluated. The higher density, lipid-functionalized structures are markedly more stable than conventional cholesterol-based structures in the presence of other unmodified liposomes and serum proteins as evidenced by fluorescence assays. Significantly, this new form of LSNA exhibits more rapid cellular uptake and increased sequence-specific toll-like receptor activation in immune reporter cell lines, making it a promising candidate for immunotherapy.

Keywords: biological stability, FRET, immunomodulation, liposomal spherical nucleic acids, SNA

1. Introduction

Lipid-functionalized oligonucleotides (LONs) are an attractive platform for many uses that include materials assembly,[1] detection,[2] and therapeutic design,[3] due to their attractive chemical and biological properties that include increased stability in serum and straightforward assembly into nanocarriers through hydrophobic interactions.[3a,d,4] LONs can also be used to synthesize spherical nucleic acids (SNAs), a class of nanomaterial that consists of a small spherical core (<100 nm) functionalized with a dense and highly oriented oligonucleotide shell.[5] The nucleic acid shell allows SNAs to readily enter cells without the need for transfection agents,[4a,6] enhances their binding affinity for protein receptors[7] and complementary oligonucleotides,[5,8] and reduces their susceptibility to degradation by endonucleases.[6] Because of these enhanced properties, SNAs have emerged as attractive agents for biodetection,[9] drug delivery,[10] gene regulation,[6,11] and immunomodulation.[12] Since the biological properties of SNAs are independent of the core type, they have been synthesized with a variety of templates including gold particles,[5] micelles,[4b,13] infinite coordination polymer particles,[14] liposomes,[4a] and proteins.[15] For in vivo biological applications, the liposomal variants are more appealing since the vesicle cores are highly biocompatible, able to encapsulate a diverse range of molecules, and readily functionalized in a modular fashion.[16]

LSNAs are typically synthesized by anchoring nucleic acids modified with hydrophobic moieties, such as cholesterol or tocopherol, into the lipid bilayer of a liposomal template.[4a,12,17] However, the fluidity of the liposomal core[18] and the hydrophilicity of the nucleic acid shell[19] make this structure intrinsically dynamic. For LSNAs, interparticle component exchange could reduce the stability of the nucleic shell and ultimately the entire SNA structure. The nature of the hydrophobic groups covalently attached to the nucleic acids can modulate the dynamics of interparticle exchange; cholesterol-modified nucleic acids have weaker and more dynamic interactions with lipid bilayers, while nucleic acids modified with diacyl chains are significantly more stable.[2,20] Furthermore, in biological environments, the presence of serum proteins and natural lipid-based structures, both of which are known to readily interact with liposome-based conjugates,[21] could further destabilize LSNAs by interacting with dissociated nucleic acid strands.

Any loss of the nucleic acid shell from the LSNAs is likely to alter their interactions with cells. Indeed, prior SNA research has shown that greater oligonucleotide density leads to increased cellular uptake.[22] Along with the dynamic behavior of LSNAs, conventional approaches to synthesizing LSNAs often result in lower oligonucleotide densities in comparison to SNAs with inorganic cores.[23] These observations point toward the importance of increasing oligonucleotide density and maintaining stability of LSNA architectures in physiological environments. Herein, we synthesized LSNA structures with different nucleic acid loadings and dynamic behaviors in an effort to establish structure-function relationships between these structures and cellular environments. To accomplish this goal, we synthesized LSNAs using different hydrophobic anchors, lipid or cholesterol, that are covalently linked to DNA (Scheme 1) and measured their stability in buffer and serum, dissociation kinetics, cellular uptake properties, and ability to engage with toll-like receptors (TLRs) critical for immune-modulation. From these studies, we determined that the LSNAs synthesized with lipid-modified DNA lead to twice the oligonucleotide loading, resulting in substantively enhanced stability, more rapid cellular internalization, and greater sequence-specific TLR-mediated immune activation.

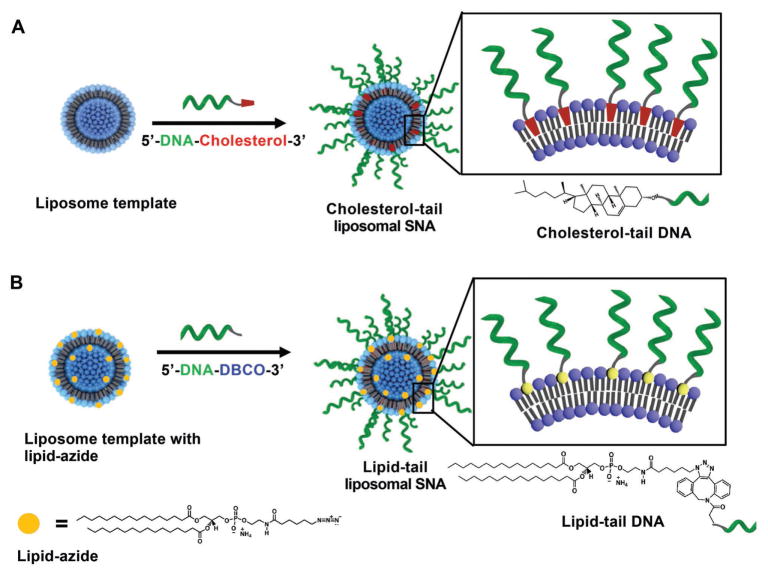

Scheme 1.

Two different functionalization strategies for LSNAs.

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Nucleic Acid Loading on Liposomes

LSNAs were synthesized by modifying the surface of small unilamellar vesicle (SUV) templates (50 nm size; Figure S1, Supporting Information) using two different functionalization strategies (Scheme 1). In the first strategy, cholesterol-tail LSNAs were synthesized via literature methods by adding cholesterol-modified DNA to 1,2-dioleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (DOPC)-based SUVs in 4-(2-hydroxyethyl)-1-piperazineethanesulfonic acid (HEPES)-buffered saline (HBS; Scheme 1A).[4a] In the second strategy, an azide-functionalized 1,2-dipalmitoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoethanolamine (DPPE) derivative, 1,2-dipalmitoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoethanolamine-N-(6-azidohexanoyl) (DPPE-Az), was used as the minor lipid component (0.5–10 mol%) in the formation of DOPC-based SUVs with azide groups presented on the surface of the vesicle (Scheme 1B). Dibenzocyclooctyl (DBCO)-modified DNA strands were then covalently conjugated to the azide groups through Cu-free click chemistry to synthesize lipid-tail LSNAs.[24] This second strategy has two potential advantages: (1) the number of potential anchoring sites (i.e., azides) can be controlled prior to surface modification through the lipid stoichiometry used to create the initial vesicle, and (2) the saturated lipid tail is more hydrophobic than cholesterol, minimizing the dissociation of oligonucleotides already anchored to the liposomal vesicle.[25]

Since the hydrophobic anchors for the two different strategies have different affinities for the liposomal template, the DNA loading for each was determined. To determine the stoichiometry that led to maximum DNA loading, increasing amounts of either DBCO-DNA or cholesterol-DNA were incubated with their respective liposomal templates overnight at 25 °C (Table 1). Following purification by size-exclusion chromatography, the number of strands per liposome was assessed. Importantly, lipid-tail LSNAs had significantly greater DNA loading compared to cholesterol-tail analogs (Table 1). This constitutes a substantive increase in DNA shell density, which should affect particle interactions with proteins and cells.

Table 1.

Number of DNA strands per particle when incubated with different ratios of liposome to DNA.

| Mole fraction of azide in liposome | |||

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| 10% | 5% | 2.5% | |

| Lipid-tail LSNAs | |||

| Ratio of DNA to total azide | Strands/liposome | ||

| 10:1 | 330 | 330 | 190 |

| 5:1 | 320 | 340 | 160 |

| 1:1 | 200 | 190 | 110 |

| Cholesterol-tail LSNA | |||

| Cholesterol DNA Added (μm DNA/mm Lipid) | Strands/liposome | ||

| 15 | 70 | ||

| 20 | 90 | ||

| 30 | 140 | ||

| 50 | 150 | ||

2.2. Dynamics of Interparticle Exchange of DNA

Although the surface DNA density is important, LSNA constructs also must remain assembled in physiological environments for it to exhibit its architecture-dependent properties. To determine the stability of the LSNAs, the kinetics of interparticle DNA exchange for both cholesterol-tail and lipid-tail LSNAs were measured in liposome-containing buffers and serum protein environments. As a reporter of the assembly state of the structures, Förster resonance energy transfer (FRET) LSNAs were synthesized using a rhodamine-labeled lipid and Cy5-labeled DNA (detailed sequences are listed in Table S1 of the Supporting Information), so that FRET can occur between the fluorophore-labeled lipids and DNA when the LSNA is fully assembled (Figure S2, Supporting Information). To assess the rate at which the DNA shell dissociated from its original liposomal template and inserted into a different lipid bilayer, FRET reporter particles, synthesized with ≈150 strands/particle, were mixed with an excess (≈100 fold by liposome) of 50 nm DOPC liposomes (without DNA). The addition of the cholesterol-tail FRET reporter LSNA to the DOPC-derived liposomes at room temperature (21 °C) and physiologic temperature (37 °C) resulted in an exponential decay of FRET signal (kobs = (2.1 ± 0.1) × 10−3 and (1.0 ± 0.08) × 10−2 s−1 respectively Figure 1B) indicating rapid dissociation of the LSNA. In contrast, lipid-tail LSNAs showed minimal decay at room temperature and dissociation rates of 7.1 ± 0.2 × 10−5 s−1 at 37 °C. Consistent with our hypothesis and previous findings, the rate of exchange between particles is significantly slower for lipid-tail LSNAs in comparison to the cholesterol-tail analogs. As a control, the LSNAs were incubated in buffer over the same time and displayed no decay (Figure 1C), indicating that disassembly of the LSNAs only occurs in the presence of other liposomes.

Figure 1.

Dissociation of LSNAs in the presence of other liposomal templates. A) A schematic representation of the dissolution process for LSNAs in the presence of other liposomes. B) The FRET ratio of the cholesterol-tail and lipid-tail LSNAs in the presence of excess DOPC liposomes. C) The FRET ratio of both LSNAs incubated in buffer.

Previous studies have reported that the rate of spontaneous dissociation of fluorophore-modified DOPE from liposomal bilayers is significantly slower (1.16 × 10−5 s−1 at 37 °C) than the dissociation rates reported here for the DNA strands modified with either cholesterol or lipid.[26] Since the rate of dissociation for lipids is significantly slower than those observed in our particles, we hypothesized that the DNA shell was dissociating much quicker than the lipid components. To confirm this hypothesis, control particles featuring rhodamine-labeled lipids and unlabeled DNA were mixed with particles containing carboxyfluorescein-labeled lipids and unlabeled DNA (see Table S2 of the Supporting Information for composition). The fluorescence spectrum was measured after 0, 0.25, and 24 h incubation at 25 °C, revealing only minimal exchange of the dye-labeled lipids (Figure S3, Supporting Information).

2.3. Dynamics in a Protein-Rich Environment

Suspecting that the protein-rich environment in serum can destabilize LSNAs by interacting with the lipid components or the DNA, either on the particle or when dissociated,[4c,27] we incubated our FRET reporter LSNAs in a 10 vol% serum-containing medium. Disruption of the LSNAs due to interactions with serum proteins would result in decreased FRET (Figure 2A). Indeed, the FRET signals decreased and the fluorescence of rhodamine-labeled lipids increased for both LSNA structures over time (Figure 2B,C), although at different rates. The lipid-tail LSNAs show a >20-fold extended half-life in comparison to the cholesterol-tail analogs with observed dissociation rates of (2.8 ± 0.4) × 10−4 and (7.9 ± 1.1) × 10−3 s−1, respectively. The increased stability of lipid-tail LSNAs should allow such structures to remain intact and enter cells via known endosomal pathways,[28] which, in the context of immunotherapy, should equate to a larger therapeutic payload. In addition, this result suggests that serum proteins actively disrupt LSNAs as evidenced by the four-fold increase in exchange rate for the lipid-tail LSNAs in the presence of serum proteins when compared to the system containing only LSNAs mixed with unmodified liposomes, but in the absence of proteins where only passive dissociative exchange is possible.

Figure 2.

Disassembly of LSNAs in serum. A) A schematic representation of the disassembly of FRET reporting LSNAs synthesized with Cy5-labeled DNA and rhodamine labeled lipids upon incubation in 10 vol% serum solution. B) Rhodamine fluorescence measured over time for cholesterol-tail and lipid tail LSNAs. C) The FRET ratio between rhodamine and Cy5 for both LSNAs.

Note that although there is a significant decrease in the FRET signal for both classes of LSNAs over the course of the experiments, a baseline level of FRET remains, which indicates that some DNA strands may remain attached to the lipid bilayer. To confirm that the decrease in FRET is due to the loss of the DNA shell and not the fluorophore-labeled lipids in the core, a LSNA composed of carboxyfluorescein- and rhodamine-labeled lipids (1 mol% each) with unlabeled cholesterol-tail DNA was incubated in a 10 vol% serum solution. The dissociation rate of the lipids from the core was significantly slower (kobs = (5.7 ± 0.2) × 10−5 s−1) than that measured between the DNA shell and the template (Figure S4, Supporting Information). This supports the conclusion that the dissociation rate of the DNA shell is faster than the disassembly of the lipid core in protein-rich environments.

Since the density of the DNA shell can potentially alter interactions between LSNAs and serum proteins due to electrostatic considerations and oligonucleotide sequence- and density-specific interactions,[29] the stabilities of the lipid-tail LSNAs were evaluated as a function of shell density. The particles with higher DNA shell densities reached equilibrium, as determined by the FRET ratio, at later time points compared to those with lower shell densities (Figure S5, Supporting Information), showing that increased DNA loading leads to longer structural retention.

Since the concentration of the particles and serum proteins could potentially impact the dissociation rates of the system, we measured the dissociation rate as a function of different serum and particle concentrations. To examine the serum-protein-concentration-dependent dissociation, the LSNAs were incubated with media containing increasing serum protein concentrations (10, 20, and 30 vol% fetal bovine serum (FBS)). There was no observable increase in dissociation rate at higher serum concentrations (Figure S6A, Supporting Information). In addition, the effect of particle concentration was evaluated by incubating two different particle concentrations, 100 × 10−9 and 500 × 10−9 M by DNA, with 10 vol% FBS (Figure S6B, Supporting Information). Again, no significant concentration dependence was observed. Taken together, these results suggest that LSNA dissociation is independent of serum protein and particle concentration for ranges typically used in cell experiments and is primarily dependent on the hydrophobic anchor attached to the DNA.

2.4. Cellular Uptake of LSNAs

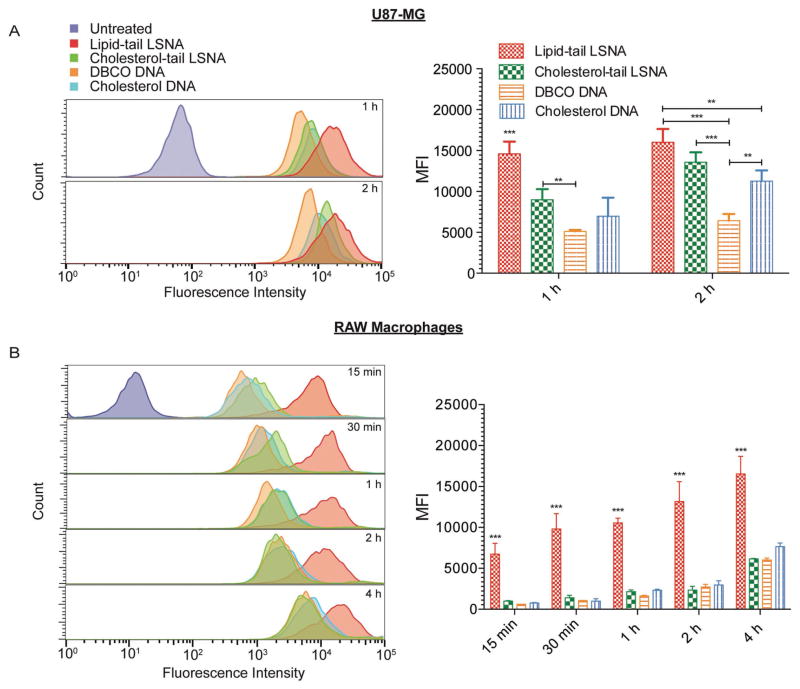

A characteristic property of SNAs is that the nucleic acid shell facilitates their rapid cellular internalization by engaging scavenger class A receptors, among others, on the cell membrane.[28] As such, increased surface loading of DNA on the LSNAs should lead to higher rates of cellular uptake. Structures that have slower dissociation rates should result in higher DNA densities facilitating cellular uptake. To study the effect of LSNA stability and DNA shell density on cellular uptake, we employed two different cell lines, U87-MG glioblastoma cells and RAW-Blue macrophages. The cells were incubated with both types of LSNAs, cholesterol-modified DNA, and DBCO-modified DNA, which were all synthesized with Cy5-labeled phosphorothioate (PS) DNA, and then evaluated using flow cytometry.

Notably the U87-MG cells showed increased uptake of the lipid-tail LSNAs after 1 h compared to the cholesterol-tail LSNAs (Figure 3A). After 2 h incubation, however, the lipid-tail LSNAs no longer displayed an advantage (Figures 3A). Confocal imaging of the cells corroborated this result, with greater Cy5 fluorescence intensity after 1 h of incubation with the lipid-tail LSNAs (Figure S8, Supporting Information). Significantly, the uptake of both types of LSNAs as well as cholesterol-tail DNA is greater than that observed for DBCO-modified PS DNA, which is not capable of assembling into a spherical architecture like the other DNA structures used.

Figure 3.

Cellular uptake of LSNAs. Histograms of cellular fluorescence intensity and the median fluorescence intensity for A) U87-MG cells and B) Raw-Blue macrophages incubated with structures incorporating Cy5-labeled DNA (**P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001; ANOVA with a Bonferroni post hoc test).

The RAW-Blue macrophages also displayed enhanced uptake of the lipid-tail LSNAs in comparison to cholesterol-tail LSNAs (Figure 3B). These cells showed rapid uptake of the lipid-tail LSNAs and greater total uptake even after 4 h of incubation (Figure 3B). Surprisingly, the cholesterol-tail LSNAs and cholesterol-modified DNA did not have any enhancement in uptake over the DBCO-modified DNA. This stands in contrast to what we observed for the glioblastoma derived U87-MG cells. The differences between these two cell lines are likely due to differences in the levels of expression of cell membrane receptors.

We hypothesized that the increased uptake of the lipid-tail LSNAs stems from its more-stable and higher-density DNA shell facilitating interactions with scavenger receptors on the cell surface, thus, enhancing cellular internalization.[22,28] To test this hypothesis, we treated U87-MG cells with Fucoidan, an inhibitor of scavenger receptors, prior to incubation with LSNAs. Following this treatment, the overall uptake of the LSNAs decreased, and no significant difference between the uptake of cholesterol-tail and lipid-tail particles was observed (Figure S9, Supporting Information). This result is consistent with the conclusion that the enhanced uptake of the lipid-tail structures at early time points stems largely from scavenger receptor-mediated endocytosis.

Since both cholesterol-tail and lipid-tail DNAs are capable of cellular internalization, due to their ability to independently form self-assembled micellar structures that mimic the SNA architecture[13] or bind nonspecifically to cell membranes,[12,30] confocal microscopy and flow cytometry data alone are not sufficient to determine if the constructs are being internalized as fully or partially intact structures. To answer this question, we measured the FRET efficiency of the particles inside cells by imaging the rhodamine fluorescence before/after photobleaching of the Cy5 dye (Figure 4). Intact particles have increased rhodamine fluorescence after photobleaching of the Cy5-labeled DNA (Figure 4A). In contrast, disassembled particles, where the Cy5-labeled DNA has detached from the initial liposomal structure, have minimal increases in rhodamine fluorescence. After 1 h of incubation, cells treated with the lipid-tail LSNAs exhibit increased FRET compared to those treated with the cholesterol-tail analogs (Figure 4C), consistent with the former being more stable. Significantly, lipid-tail LSNAs loaded with higher DNA densities (300 strands/LSNA) continued to retain more DNA strands per liposome after 1 and 2 h of incubation compared to those assembled with lower DNA densities (≈150 strands/LSNA). The amount of observed FRET continued to decrease for the lipid-tail LSNAs at the 2 h time point. After 24 h of incubation, no significant differences in FRET were detected and only minimal FRET was observed for any of the structures, suggesting that the LSNAs gradually disassemble inside cells as a function of time.

Figure 4.

Acceptor photobleaching FRET imaging of LSNAs. Confocal images of LSNAs synthesized with Cy5-labeled DNA (red) attached to rhodamine-labeled liposomes (green) A) before and B) after photobleaching of Cy5. The cell nuclei are stained with Hoechst (blue). A dashed box indicates the region of interest (ROI) where photobleaching occurs. Enlarged images of the ROI for Cy5 and rhodamine fluorescence are shown below each image. Scale bars = 10 μm. C) The FRET efficiency of LSNAs internalized by cells as determined by measuring the fluorescence intensity of rhodamine-labeled lipids before and after photobleaching of the Cy5-labeled DNA (*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001; ANOVA with a Bonferroni post hoc test).

2.5. Activation of Toll-Like Receptors for Immunotherapeutics

To assess the ability of both types of LSNAs to activate therapeutic targets inside cells, we synthesized LSNAs with immunostimulatory unmethylated CpG-rich DNA (1826 ODN).[31] These DNA sequences are known to activate toll-like receptor 9 (TLR9), which modulates innate immunity by stimulating cytokine production.[32] Incubating these LSNAs with RAW-Blue macrophages, which are modified to secrete alkaline phosphatase upon stimulation of TLRs for a colorimetric readout of immune-stimulation, allows us to compare their immune stimulatory activity. As shown in Figure 5A, the lipid-tail LSNAs show modestly increased activity at lower concentrations compared to cholesterol-tail analogs. More importantly, pulse-chase experiments conducted at 250 × 10−9 M concentration reveal significantly faster activation of the macrophages (Figure 5B) by the lipid-tail LSNA formulations, presumably a consequence of more rapid uptake by cells (Figure 3B).

Figure 5.

Activation of RAW Blue macrophages by LSNAs. A) TLR9 activation resulting from overnight incubation with CpG and control (T25) LSNAs along with the linear CpG DNA. B) TLR9 activation from pulse-chase treatment with CpG LSNAs. The activation is normalized to that measured after overnight incubation at the same concentration (*P < 0.01, ANOVA with Bonferroni post hoc test).

3. Conclusions

In summary, we have evaluated the stability and biological behavior of LSNAs synthesized with either lipid- or cholesterol-modified oligonucleotides. Importantly, this work demonstrates that a synthetic route of directly modifying lipid-head groups on liposomes with DNA leads to higher nucleic acid shell densities and increased stability in physiological environments. These combined properties result in enhanced interactions with cells and significant advantages in the context of sequence-specific immune modulation. Taken together, this work outlines important structure-function principles for LSNAs that will directly impact the design of nanomaterials for novel therapeutic platforms.

4. Experimental Section

Materials

Unless otherwise noted, all reagents were purchased from commercial sources and used as received. For oligonucleotide synthesis, all phosphoramidites and reagents were purchased from Glen Research, Co. (Sterling, VA, USA). All lipids were purchased from Avanti Polar Lipids, Inc. (Alabaster, AL, USA) either in dry powder form or as a chloroform solution and used without further purification. All other reagents were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich, Co. (St. Louis, MO, USA). Ultrapure deionized (DI) H2O (18.2 MΩ cm resistivity) was obtained from a Milli-Q Biocel system (Millipore Co., Billerica, MA, USA).

Instrumentation

UV–vis absorbance spectra were collected on a Varian Cary 5000 UV–vis spectrometer (Varian Inc., Palo Alto, CA, USA) using quartz cuvettes with a 1 cm path length.

Matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization time-of-flight (MALDI-ToF) mass spectrometric data were obtained on a Bruker AutoFlex III MALDI-ToF mass spectrometer (Bruker Daltonics Inc., Billerica, MA, USA). For MALDI-ToF analysis, the matrix was prepared by mixing an aqueous solution of ammonium hydrogen citrate (0.6 μL of a 35 wt% solution (15 mg in 30 μL of H2O)) and 3-hydroxypicolinic acid (Sigma-Aldrich, 2 mg in H2O:MeCN (30 μL of a 1:1 v/v mixture)). An aliquot of the DNA (≈0.5 μL of a 150 × 10−6 M solution) was then mixed with the matrix (1:1) and the resulting solution was added to a steel MALDI-ToF plate and dried under ambient conditions for 1 h before analysis. Samples were detected as negative ions using the linear mode. The laser was typically operated at 10–20% power with a sampling speed of 10 Hz. Each measurement averaged 500 scans with the following parameters: ion source voltage 1 = 20 kV, ion source voltage 2 = 18.5 kV, lens voltage = 8.5 kV, linear detector voltage = 0.6 kV, deflection mass = 3000 Da.

Centrifugation was carried out in a temperature-controlled Eppendorf centrifuge 5430R (Eppendorf AG, Hauppauge, NY, USA). Dynamic light scattering (DLS) and zeta potential measurements were collected on a Zetasizer Nano ZS (Malvern Instruments, UK) equipped with a He–Ne laser (633 nm).

Oligonucleotide Synthesis

Phosphorothioate oligonucleotides were synthesized on CPG supports using an automated nucleotide system (model: MM12, BioAutomation Inc., Plano, TX, USA) and were purified using high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC). All oligonucleotides used in this study have PS backbone modifications. For details on sequences synthesized (Table S1, Supporting Information) and purification methods, see Section S1 (Supporting Information).

Synthesis of Small Unilamellar Vesicles

SUVs were synthesized using literature methods.[4a] A brief description of the synthesis, purification, and characterization of these structures along with the composition of the liposomes used for the studies (Table S2, Supporting Information) can be found in Section S2 (Supporting Information).

Synthesis and Purification of Different LSNAs

For cholesterol-tail LSNAs, a 3′-cholesterol-tail oligonucleotide was added to the SUV colloids (1.3 × 10−3 M phospholipid concentration, final volume 1 mL) and was shaken overnight. For lipid-tail LSNAs, an aliquot of the desired DBCO-tail oligonucleotides was added to a N3-DPPE containing SUV (0.5 × 10−3 M total phospholipid concentration, final volume 1 mL) with a DNA-DBCO:surface N3-DPPE lipid molar ratio of 2:1. The mixture was shaken overnight. Both structures were purified via size-exclusion chromatography on a Sepharose CL-4B column (Sigma-Aldrich) and the particle size distribution was analyzed using DLS. For details on the DLS measurements, see Section S3 (Supporting Information).

The density of the nucleic acid shell was determined by first dissociating the particles in sodium dodecyl sulfate and then measuring the absorbance at 260 nm via UV–vis spectroscopy to calculate the DNA concentration. The amount of lipid was determined by measuring the total phosphorus content via inductively coupled plasma mass spectroscopy (Thermo Fisher X Series II, Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc., Waltham, MA, USA) and subtracting the phosphorus content contributed by the DNA backbone. An alternative method to determine the density was also used. The absorbance spectrum of LSNAs synthesized with Cy5 labeled DNA and 1 mol% rhodamine labeled lipid were measured. The peak absorbance of the Cy5 and rhodamine (corrected to remove any Cy5 absorbance contribution) were used to measure the relative amount of DNA to lipid.

FRET-Based Transfer Studies

A solution of FRET reporter LSNA (Table S2, Supporting Information, 0.1 × 10−6 M by final [oligonucleotide], final volume 1 mL) was aliquoted into a quartz cuvette at room temperature. A ≈100-fold excess of DOPC liposomes was added and quickly pipetted up and down (within 3 s) to mix uniformly. The fluorescence of the FRET reporter particles was monitored over 3 h (Rhodamine/Cy5, excitation at 560 nm, emission at 583 and 672 nm, 3 nm slit width) using a Fluorlog-3 (HORIBA Jobin Yvon Inc., Edison, NJ, USA).

For experiments measuring lipid dissociation, cholesterol-control rhodamine particles (Table S2, Supporting Information, 0.1 × 10−6 M by final [oligonucleotide], volume 1 mL) were aliquoted into an Eppendorf tube at room temperature. An equimolar aliquot of cholesterol-control fluorescein particles (Table S2, Supporting Information) was added and quickly pipetted up and down (within 3 s) to mix uniformly. The fluorescence spectrum was then taken after incubation at 25 °C at 0, 0.25, and 24 h, with a plate reader (Synergy H4, BioTek Instruments, Inc., Winooski, VT, USA, 9.0 nm slit width, Excitation 480 nm). The FRET ratio was calculated using the formula[33]

| (1) |

where IA is the acceptor intensity and ID is the donor intensity measured at their respective peak wavelengths.

Serum Stability Studies

FRET reporter particles (100 × 10−9 M [oligonucleotide]) were added to a serum-containing solution (10 vol% FBS in HBS) and mixed well for 3 s. The fluorescence of the LSNAs was monitored with a plate reader (Synergy H4, excitation at 560 nm, emission at 583 and 672 nm, 9.0 nm slit width) at 37 °C. For details on DNA loading and concentration dependent serum stability studies, see Section S4 (Supporting Information).

Control experiments consisting of LSNAs assembled with 1 mol% fluorescein- and rhodamine-labeled lipids with unlabeled cholesterol-modified DNA (100 × 10−9 M final [DNA]) were utilized to measure the exchange rate of the lipids in 10 vol% FBS. The fluorescence was monitored on a plate reader over 10 h at 30 min intervals (excitation at 480 × 10−9 M, emission at 583 nm and 550 nm, 9 nm slit width). A final reading was performed after 36 h to observe the equilibrium fluorescence.

Cell Culture

Confocal imaging and flow cytometry were performed on U-87 MG cells (epithelial, glioblastoma) using the recommended culture conditions in complete growth media (minimum essential medium supplemented with FBS (10 vol%), penicillin (0.2 units mL−1), and streptomycin (0.1 μg mL−1)).

RAW-Blue cells (InvivoGen, CA, USA), which are derivatives of RAW 264.7 macrophage cells stably expressing a secreted alkaline phosphatase under a NF-κB promoter, were cultured as recommended by the supplier in complete growth media (Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium supplemented with 10 vol% heat inactivated FBS, penicillin (0.2 units mL−1), streptomycin (0.1 μg mL−1), Normocin (100 μg mL−1), and L-glutamine (2 × 10−3 M)).

Flow Cytometry

A comparative cell-uptake study between the two types of LSNAs (cholesterol-tail and lipid-tail constructs) was carried out using U87MG cells. Cells were plated at 20 000 cells per well in a 96 well plate in complete growth media. The cells were placed in the incubator to recover overnight. The following day, the cells were treated with both cholesterol- and lipid-tail LSNAs, cholesterol-DNA, and DBCO-DNA with a final DNA concentration 0.5 × 10−6 M for 1, 2, and 4 h. After each time point, the cells were triple washed with 1× PBS, trypsinized (5% trypsin, 30 μL for 5 min at 37 °C), and fixed in 200 μL of 4% paraformaldehyde. Flow cytometry was performed on the cells using the red laser and red fluorescence channel on a Guava easyCyte 8HT instrument (Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA). The distribution of cell fluorescence of the gated-cells was collected and the MFI was calculated. Error-values were determined using the standard deviation of the median signal from three different wells. For the scavenger receptor inhibition studies, the cells were incubated with Fucoidan (50 μg mL−1) for 30 min prior to the addition of the respective oligonucleotide structures, and flow cytometry was performed after 1 h of incubation with the LSNAs using the aforementioned protocol.

Confocal Microscopy

U87MG cells were seeded in an 8 well chamber slide (German #1.5, LabTek II, Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc., Waltham, MA, USA) at 10 000 cells per well and incubated overnight. FRET reporter LSNAs (0.1 × 10−6 M by oligonucleotide) were then incubated with the cells in complete growth media for 1 and 24 h. The media was removed and the cells were rinsed with PBS and fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 10 min at room temperature. The paraformaldehyde was removed and the cells were rehydrated in PBS for imaging. The cell nuclei were stained with Hoechst 3342 (Invitrogen, Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc., Carlsbad, CA, USA) following the manufacturer’s instructions. Confocal microscopy imaging of these cells was carried out on a Zeiss LSM 800 inverted laser-scanning confocal microscope (Carl Zeiss, Inc., Thornwood, NY, USA) at 40 × and 63 × magnification. Acceptor photobleaching experiments were performed by zooming into and exciting the Cy5 dye in a small region of interest (ROI) with a 640 nm laser at 100% power for 40 cycles. Rhodamine and Cy5 fluorescence intensities were measured before and after photobleaching of the Cy5 dye. The FRET efficiencies were determined by comparing the intensity of the rhodamine fluorescence intensity within the ROI before and after Cy5 photobleaching using ImageJ software (Available free of charge through https://imagej.nih.gov/ij/). Approximately 10 cells per ROI were imaged for each condition for calculating FRET efficiencies, which were determined using the following equation after subtraction of the background fluorescence:

| (2) |

Cell Stimulation Studies

HEK-Blue-mTLR9 cells were plated in 96 well plates at a density of 50 000 cells per well in complete growth media (see Section S9 for details on media, 200 μL of media per well). Immediately after plating, the cells were treated with cholesterol-tail or lipid-tail LSNAs and incubated at 37 °C for 16 h. The assay was developed using the manufacturers recommended protocol, which is described in Section S6 (Supporting Information).

For the pulse-chase experiments, HEK-Blue-mTLR9 were plated as described above. Immediately after plating, the cells were treated with the cholesterol-tail or lipid-tail LSNAs (see Table S1 of the Supporting Information) at 250 × 10−9 M final DNA concentration per well. The cells were incubated with the different LSNAs for 15, 30, 45, 60, 90, and 180 min. After each time point, the media was removed and replaced with fresh media and further incubated at 37 °C for 16 h. The Quanti-Blue analysis then proceeded as described in Section S6 (Supporting Information).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

B.M. and R.J.B. contributed equally to this work. Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Cancer Institute of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number U54CA199091. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. This work made use of the MALDI-ToF equipment (purchased with support from Northwestern University and the State of Illinois) at the NU Integrated Molecular Structure Education and Research Center (IMSERC).

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Supporting Information is available from the Wiley Online Library or from the author.

Contributor Information

Dr. Brian Meckes, Department of Chemistry, International Institute for Nanotechnology, Evanston, IL 60208, USA

Dr. Resham J. Banga, Department of Chemical and Biological Engineering, Northwestern University, International Institute for Nanotechnology, Evanston, IL 60208, USA

Prof. SonBinh T. Nguyen, Department of Chemistry, International Institute for Nanotechnology, Evanston, IL 60208, USA

Prof. Chad A. Mirkin, Department of Chemistry, International Institute for Nanotechnology, Evanston, IL 60208, USA. Department of Chemical and Biological Engineering, Northwestern University, International Institute for Nanotechnology, Evanston, IL 60208, USA

References

- 1.a) Thompson MP, Chien MP, Ku TH, Rush AM, Gianneschi NC. Nano Lett. 2010;10:2690. doi: 10.1021/nl101640k. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Dave N, Liu J. ACS Nano. 2011;5:1304. doi: 10.1021/nn1030093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pfeiffer I, Höök F. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126:10224. doi: 10.1021/ja048514b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.a) Patwa A, Gissot A, Bestel I, Barthelemy P. Chem Soc Rev. 2011;40:5844. doi: 10.1039/c1cs15038c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Raouane M, Desmaële D, Urbinati G, Massaad-Massade L, Couvreur P. Bioconjugate Chem. 2012;23:1091. doi: 10.1021/bc200422w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Soutschek J, Akinc A, Bramlage B, Charisse K, Constien R, Donoghue M, Elbashir S, Geick A, Hadwiger P, Harborth J, John M, Kesavan V, Lavine G, Pandey RK, Racie T, Rajeev KG, Rohl I, Toudjarska I, Wang G, Wuschko S, Bumcrot D, Koteliansky V, Limmer S, Manoharan M, Vornlocher HP. Nature. 2004;432:173. doi: 10.1038/nature03121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Liu H, Moynihan KD, Zheng Y, Szeto GL, Li AV, Huang B, Van Egeren DS, Park C, Irvine DJ. Nature. 2014;507:519. doi: 10.1038/nature12978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.a) Banga RJ, Chernyak N, Narayan SP, Nguyen ST, Mirkin CA. J Am Chem Soc. 2014;136:9866. doi: 10.1021/ja504845f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Liu H, Zhu Z, Kang H, Wu Y, Sefan K, Tan W. Chem – Eur J. 2010;16:3791. doi: 10.1002/chem.200901546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Wolfrum C, Shi S, Jayaprakash KN, Jayaraman M, Wang G, Pandey RK, Rajeev KG, Nakayama T, Charrise K, Ndungo EM, Zimmermann T, Koteliansky V, Manoharan M, Stoffel M. Nat Biotechnol. 2007;25:1149. doi: 10.1038/nbt1339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Yoshina-Ishii C, Boxer SG. J Am Chem Soc. 2003;125:3696. doi: 10.1021/ja029783+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e) Wang F, Zhang X, Liu Y, Lin ZYW, Liu B, Liu J. Angew Chem, Int Ed Engl. 2016;55:12063. doi: 10.1002/anie.201606603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mirkin CA, Letsinger RL, Mucic RC, Storhoff JJ. Nature. 1996;382:607. doi: 10.1038/382607a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rosi NL, Giljohann DA, Thaxton CS, Lytton-Jean AK, Han MS, Mirkin CA. Science. 2006;312:1027. doi: 10.1126/science.1125559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chinen AB, Guan CM, Mirkin CA. Angew Chem, Int Ed Engl. 2015;54:527. doi: 10.1002/anie.201409211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cutler JI, Auyeung E, Mirkin CA. J Am Chem Soc. 2012;134:1376. doi: 10.1021/ja209351u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.a) Seferos DS, Giljohann DA, Hill HD, Prigodich AE, Mirkin CA. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129:15477. doi: 10.1021/ja0776529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Chen T, Wu CS, Jimenez E, Zhu Z, Dajac JG, You M, Han D, Zhang X, Tan W. Angew Chem, Int Ed Engl. 2013;125:2066. doi: 10.1002/anie.201209440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Zheng D, Seferos DS, Giljohann DA, Patel PC, Mirkin CA. Nano Lett. 2009;9:3258. doi: 10.1021/nl901517b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Qu X, Zhu D, Yao G, Su S, Chao J, Liu H, Zuo X, Wang L, Shi J, Wang L, Huang W, Pei H, Fan C. Angew Chem, Int Ed Engl. 2017;56:1855. doi: 10.1002/anie.201611777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e) Liu B, Liu J. J Am Chem Soc. 2017;139:9471. doi: 10.1021/jacs.7b04885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.a) Zheng J, Zhu G, Li Y, Li C, You M, Chen T, Song E, Yang R, Tan W. ACS Nano. 2013;7:6545. doi: 10.1021/nn402344v. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Tan X, Lu X, Jia F, Liu X, Sun Y, Logan JK, Zhang K. J Am Chem Soc. 2016;138:10834. doi: 10.1021/jacs.6b07554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Li J, Fan C, Pei H, Shi J, Huang Q. Adv Mater. 2013;25:4386. doi: 10.1002/adma.201300875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.a) Giljohann DA, Seferos DS, Prigodich AE, Patel PC, Mirkin CA. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;131:2072. doi: 10.1021/ja808719p. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Ryou SM, Kim S, Jang HH, Kim JH, Yeom JH, Eom MS, Bae J, Han MS, Lee K. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2010;398:542. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2010.06.115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Zheng D, Giljohann DA, Chen DL, Massich MD, Wang XQ, Iordanov H, Mirkin CA, Paller AS. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109:11975. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1118425109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Jensen SA, Day ES, Ko CH, Hurley LA, Luciano JP, Kouri FM, Merkel TJ, Luthi AJ, Patel PC, Cutler JI, Daniel WL, Scott AW, Rotz MW, Meade TJ, Giljohann DA, Mirkin CA, Stegh AH. Sci Transl Med. 2013;5:209ra152. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3006839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Radovic-Moreno AF, Chernyak N, Mader CC, Nallagatla S, Kang RS, Hao LL, Walker DA, Halo TL, Merkel TJ, Rische CH, Anantatmula S, Burkhart M, Mirkin CA, Gryaznov SM. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2015;112:3892. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1502850112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.a) Li Z, Zhang Y, Fullhart P, Mirkin CA. Nano Lett. 2004;4:1055. [Google Scholar]; b) Banga RJ, Meckes B, Narayan SP, Sprangers AJ, Nguyen ST, Mirkin CA. J Am Chem Soc. 2017;139:4278. doi: 10.1021/jacs.6b13359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Calabrese CM, Merkel TJ, Briley WE, Randeria PS, Narayan SP, Rouge JL, Walker DA, Scott AW, Mirkin CA. Angew Chem, Int Ed Engl. 2015;54:476. doi: 10.1002/anie.201407946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brodin JD, Sprangers AJ, McMillan JR, Mirkin CA. J Am Chem Soc. 2015;137:14838. doi: 10.1021/jacs.5b09711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zelphati O, Szoka FC. J Controlled Release. 1996;41:99. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sprangers AJ, Hao L, Banga RJ, Mirkin CA. Small. 2016;13:1602753. doi: 10.1002/smll.201602753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Reddy AS, Warshaviak DT, Chachisvilis M. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2012;1818:2271. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2012.05.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dayani Y, Malmstadt N. Biomacromolecules. 2013;14:3380. doi: 10.1021/bm401155a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.a) van der Meulen SAJ, Dubacheva GV, Dogterom M, Richter RP, Leunissen ME. Langmuir. 2014;30:6525. doi: 10.1021/la500940a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Gambinossi F, Banchelli M, Durand A, Berti D, Brown T, Caminati G, Baglioni P. J Phys Chem B. 2010;114:7338. doi: 10.1021/jp100730x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kim C-K, Kim H-S, Lee B-J, Han J-H. Arch Pharm Res. 1991;14:336. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Giljohann DA, Seferos DS, Patel PC, Millstone JE, Rosi NL, Mirkin CA. Nano Lett. 2007;7:3818. doi: 10.1021/nl072471q. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hurst SJ, Lytton-Jean AK, Mirkin CA. Anal Chem. 2006;78:8313. doi: 10.1021/ac0613582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Baskin JM, Prescher JA, Laughlin ST, Agard NJ, Chang PV, Miller IA, Lo A, Codelli JA, Bertozzi CR. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:16793. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0707090104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.a) Gilbert DB, Tanford C, Reynolds JA. Biochemistry. 1975;14:444. doi: 10.1021/bi00673a035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Smith R, Tanford C. J Mol Biol. 1972;67:75. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(72)90387-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Silvius JR, Leventis R. Biochemistry. 1993;32:13318. doi: 10.1021/bi00211a045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zelphati O, Uyechi LS, Barron LG, Szoka FC. Biochim Biophys Acta, Lipids Lipid Metab. 1998;1390:119. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2760(97)00169-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Choi CH, Hao L, Narayan SP, Auyeung E, Mirkin CA. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2013;110:7625. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1305804110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zwanikken JW, Guo P, Mirkin CA, Olvera de la Cruz M. J Phys Chem C. 2011;115:16368. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Luo D, Saltzman WM. Nat Biotechnol. 2000;18:33. doi: 10.1038/71889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ramirez-Ortiz ZG, Specht CA, Wang JP, Lee CK, Bartholomeu DC, Gazzinelli RT, Levitz SM. Infect Immun. 2008;76:2123. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00047-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cooper CL, Davis HL, Morris ML, Efler SM, Al Adhami M, Krieg AM, Cameron DW, Heathcote J. J Clin Immunol. 2004;24:693. doi: 10.1007/s10875-004-6244-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.a) Jiwpanich S, Ryu JH, Bickerton S, Thayumanavan S. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132:10683. doi: 10.1021/ja105059g. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Xie M, Wang S, Singh A, Cooksey TJ, Marquez MD, Bhattarai A, Kourentzi K, Robertson ML. Soft Matter. 2016;12:6196. doi: 10.1039/c6sm00297h. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.