Abstract

Background

Previous investigations in adult smokers from the COPDGene Study have shown that early-life respiratory disease is associated with reduced lung function, COPD, and airway thickening. Using 5-year follow-up data, we assessed disease progression in subjects who had experienced early-life respiratory disease. We hypothesized that there are alternative pathways to reaching reduced FEV1 and that subjects who had childhood pneumonia, childhood asthma, or asthma-COPD overlap (ACO) would have less lung function decline than subjects without these conditions.

Methods

Subjects returning for 5-year follow-up were assessed. Childhood pneumonia was defined by self-reported pneumonia at < 16 years. Childhood asthma was defined as self-reported asthma diagnosed by a health professional at < 16 years. ACO was defined as subjects with COPD who self-reported asthma diagnosed by a health-professional at ≤ 40 years. Smokers with and those without these early-life respiratory diseases were compared on measures of disease progression.

Results

Follow-up data from 4,915 subjects were examined, including 407 subjects who had childhood pneumonia, 323 subjects who had childhood asthma, and 242 subjects with ACO. History of childhood asthma or ACO was associated with an increased exacerbation frequency (childhood asthma, P < .001; ACO, P = .006) and odds of severe exacerbations (childhood asthma, OR, 1.41; ACO, OR, 1.42). History of childhood pneumonia was associated with increased exacerbations in subjects with COPD (absolute difference [β], 0.17; P = .04). None of these early-life respiratory diseases were associated with an increased rate of lung function decline or progression on CT scans.

Conclusions

Subjects who had early-life asthma are at increased risk of developing COPD and of having more active disease with more frequent and severe respiratory exacerbations without an increased rate of lung function decline over a 5-year period.

Trial Registry

ClinicalTrials.gov; No. NCT00608764; https://clinicaltrials.gov.

Key Words: asthma-COPD overlap, childhood asthma, childhood pneumonia, COPD, respiratory exacerbations

Abbreviations: ACO, asthma-COPD overlap; β, absolute difference; GOLD, Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease; HU, Hounsfield units; PRM, parametric response mapping; SGRQ, St. George's Respiratory Questionnaire; SRWA-Pi10, square root of the wall area of a hypothetical airway with 10-mm internal perimeter

Early-life respiratory conditions, including pneumonia and asthma, increase the risk for the development of COPD.1, 2, 3, 4, 5 Classically, COPD is thought of as a disease of adult smokers and is characterized by rapid lung function decline.3, 6 An emerging subtype of COPD is being defined in a subset of subjects who, due to childhood respiratory disease, never achieve the expected maximal FEV1 in young adulthood.1, 5, 7 These patients are more likely reach the diagnostic threshold for COPD even with normal age-related lung function decline.3 Understanding the progression of COPD in this population will be an important factor in personalizing management and treatment plans.

We previously examined subjects who reported a history of childhood pneumonia, childhood asthma, and asthma-COPD overlap (ACO) in phase 1 of COPDGene, a multicenter observational cohort of adult smokers.1, 8, 9, 10 Childhood pneumonia was associated with reduced lung function, COPD, and increased airway disease on chest CT scans.1 Childhood asthma was associated with smaller segmental airways.9 Subjects with ACO were younger with a lower lifetime smoking intensity but had FEV1 reductions similar to those of patients with COPD but without ACO, implying an additional mechanism for their reduced lung function.

The current study used 5-year follow-up data from phase 2 of COPDGene to examine disease progression in three independent subject groups of current and former smokers: childhood pneumonia, childhood asthma, and ACO. We hypothesized that these early-life respiratory diseases will identify subjects with less lung function decline at the time of 5-year follow-up. To assess this, we independently compared subjects from this cohort in three separate analyses: (1) subjects who experienced childhood pneumonia vs those who did not, (2) subjects who experienced childhood asthma vs those who did not, and (3) subjects with ACO vs those with COPD alone (e-Fig 1).

Methods

Study Subjects

COPDGene enrolled 10,199 current and former smokers with and without COPD in phase 1 from 2008 to 2011. This investigation evaluates the first 4,915 subjects returning for 5-year follow-up in phase 2 (September 24, 2016 data set) (e-Fig 1). This study was approved by the institutional review boards (e-Appendix 1) at each of the 21 clinical sites, and all participants provided written informed consent.10 At enrollment, subjects were 45 to 80 years of age and non-Hispanic white or African American and had at least a 10-pack-year smoking history. Subjects were excluded if they had a history of lung disease other than COPD or asthma, if they were nonsmokers, or if they had undergone lung transplantation or lung volume reduction surgery. Study protocol, enrollment criteria, and data collection forms were previously described and are available at http://www.copdgene.org.10, 11

Participants completed a modified American Thoracic Society Respiratory Epidemiology Questionnaire, Modified Medical Research Council dyspnea scale, and questionnaires related to demographics and medical history.11, 12, 13 Quality of life was assessed using the St. George's Respiratory Questionnaire (SGRQ) with permissions obtained for instrument use.14 Subjects completed a standardized spirometry protocol (ndd EasyOne Spirometer) before and after administration of albuterol. Quantitative image analysis used Thirona software (http://www.thirona.eu). Inspiratory and expiratory chest CT scans were available for 72% and 62% of phase 2 participants, respectively. Emphysema was quantified by inspiratory scan low-attenuation areas < –950 Hounsfield units (HU) and by the adjusted density of lung HU at which < 15% of the voxels had the lowest attenuation numbers at full inspiration. Gas trapping was quantified on expiratory scan at < –856 HU. Parametric response mapping (PRM) paired inspiratory and expiratory CT images to define emphysema and to assess functional small airways disease as a measure of nonemphysematous air trapping.15 Airway measurements assessed the square root of the wall area of a hypothetical airway with 10-mm internal perimeter (SRWA-Pi10) and were available for 20% of participants.16, 17

Statistical Analysis

Childhood pneumonia was defined by a self-report of first pneumonia at < 16 years or during childhood.1 Childhood asthma was defined as a self-report of asthma diagnosed by a health professional with age of onset at < 16 years or during childhood.1 ACO was defined as subjects with COPD who self-reported asthma diagnosed by a health professional with age of onset at ≤ 40 years or during childhood.1, 8, 18, 19 COPD was defined as Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) 2007 spirometry grades 2 to 4, corresponding to a postbronchodilator FEV1/ FVC ratio < 0.7 with FEV1 < 80% predicted.20

Mortality data were compiled using the Social Security Death Index through the COPDGene Longitudinal Follow-up Program (September 2016 data set). Interval development of COPD diagnosis was defined as a subject without GOLD grade 2 to 4 COPD at visit 1 but with it at visit 2. Chronic bronchitis was defined by cough and phlegm production lasting at least 3 months per year for at least 2 years. Respiratory exacerbations were defined by the use of antibiotics or systemic steroids, or both, for an acute respiratory illness. Severe exacerbations required an ED visit or hospitalization.

We performed three independent comparisons: (1) subjects who had childhood pneumonia vs those who did not, (2) subjects who had childhood asthma vs those who did not, and (3) subjects with ACO vs COPD alone (e-Fig 1). Demographics, respiratory symptoms/diseases, lung function, and chest CT scan measurements were assessed using R, version 3.1.1 (R Project for Statistical Computing). Tests used and covariates adjusted for are detailed in Table 1, Table 2, Table 3, Table 4 and e-Tables 1 and 2. Multivariable analyses used logistic regression, linear regression, or linear mixed models. Linear mixed models assessed two measures per subject, comparing visits 1 and 2, with intercept computed at the level of the subject, the only variable considered as a random effect. Subjects with missing or unclassifiable responses were removed from specific analyses.

Table 1.

COPDGene Phase 2 Subject Characteristics

| Characteristic |

Childhood Pneumonia N = 857 |

No Childhood Pneumonia N = 9,306 |

P Value | Childhood Asthma N = 730 |

No Childhood Asthma N = 9,417 |

P Value | Asthma-COPD Overlap N = 569 |

COPD N = 3,110 |

P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Phase 1 subjects | |||||||||

| Phase 2 subjects, No. (%) | 407 (47) | 4,491 (48) | .69 | 323 (44) | 4,563 (48) | .03 | 242 (43) | 1,359 (44) | .64 |

| Male sex, No. (%)a,d | 202 (50) | 2,269 (51) | .77 | 157 (49) | 2312 (51) | .51 | 107 (44) | 760 (56) | .001 |

| Mean age, (SD),c y | 67 (8) | 65 (9) | < .001 | 64 (8) | 66 (9) | < .001 | 65 (8) | 69 (8) | < .001 |

| Non-Hispanic white, No. (%)a,d | 350 (86) | 3,165 (70) | < .001 | 200 (62) | 3305 (72) | < .001 | 157 (65) | 1,099 (81) | < .001 |

| African American, No. (%)a,d | 57 (14) | 1,326 (30) | 123 (38) | 1258 (28) | 85 (35) | 260 (19) | |||

| Pack-years of smoking (SD)b | 50 (27) | 44 (24) | < .001 | 43 (23) | 44 (24) | .21 | 46 (24) | 53 (26) | < .001 |

| Current smoking, No. (%)a,d | 134 (33) | 1,698 (38) | .06 | 125 (39) | 1,707 (37) | .69 | 82 (34) | 390 (29) | .12 |

| COPD at enrollment, No. (%)a,d | 175 (54) | 1,429 (41) | < .001 | 152 (61) | 1,446 (40) | < .001 | 242 (100) | 1,359 (100) | NA |

NA = not available.

Univariate analysis with χ2 test.

Univariate analysis with Wilcoxon rank sum test.

Univariate analysis with t test.

Percentages are relative to total number of phase 2 subjects.

Table 2.

Disease Progression in Childhood Pneumonia

| Variable | Childhood Pneumonia N = 407 |

No Childhood Pneumonia N = 4,491 |

Impact of Childhood Pneumoniaa |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | 95% CI | P Value | |||

| Development of COPD, No. (%)b,e,f | 30 (7) | 313 (7) | 1.04 | 0.69-1.52 | .84 |

| Development of oxygen requirement, No. (%)b,e,f | 32 (8) | 286 (6) | 1.09 | 0.73-1.59 | .66 |

| Development of chronic bronchitis, No. (%)b,e,f,h | 31 (8) | 359 (8) | 0.92 | 0.61-1.33 | .66 |

| Had a severe COPD exacerbation in prior y, No. (%)b,e,f,g,h | 48 (12) | 411 (9) | 1.23 | 0.87-1.71 | .23 |

| β | SE | P Value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of COPD exacerbations in prior y, mean (SD)c,e,f,g,h | 0.42 (0.86) | 0.30 (0.79) | 0.06 | 0.04 | .10 |

| FEV1 postbronchodilator, % predicted, mean Δ (SD)d,e | –1.64 (11) | –1.98 (11) | 0.33 | 0.55 | .54 |

| FEV1 postbronchodilator, mL, mean Δ (SD)d,e,f,i | –196 (279) | –202 (287) | 8.32 | 15.03 | .58 |

| FVC postbronchodilator, % predicted, mean Δ (SD)d,e | –1.83 (12) | –2.11 (12) | 0.30 | 0.62 | .63 |

| FVC postbronchodilator, mL, mean Δ (SD)d,e,f,i | –250 (417) | –248 (424) | 3.56 | 22.52 | .87 |

| St. George’s Respiratory Questionnaire score, mean Δ (SD)d,e,f,g | –0.57 (17) | 0.29 (15) | Model does not converge | ||

| Modified Medical Research Council dyspnea scale, mean Δ (SD)d,e,f,g | –0.05 (1.13) | 0.07 (1.24) | –0.11 | 0.06 | .09 |

| 6-min walk distance in feet, mean Δ (SD)d,e,f,g | –154 (333) | –129 (363) | –23.90 | 18.85 | .21 |

| CT scan measuresk | |||||

| Emphysema progression | |||||

| PRM emphysema, % at –950 HU, mean Δ (SD)d,e,f,h,j | 0.45 (4) | 0.71 (3) | –0.03 | 0.20 | .86 |

| Adjusted density, mean Δ (SD)d,e,f,h,j | –0.05 (12) | –0.83 (11) | –0.33 | 0.50 | .51 |

| Air trapping progression | |||||

| Gas trapping %, expiratory scan at –856 HU, mean Δ (SD)d,e,f,h,j | 1.14 (9) | 1.21 (9) | 0.48 | 0.51 | .34 |

| PRM functional small airway disease, mean Δ (SD)d,e,f,h,j | 1.09 (7) | 0.92 (7) | 0.56 | 0.43 | .19 |

| Airway thickening progression | |||||

| SRWA-Pi10 (SD), mean Δ (SD)d,e,f,h,j | 0.06 (0.29) | 0.04 (0.30) | 0.02 | 0.03 | .57 |

HU = Hounsfield units; PRM = parametric response mapping; SRWA-Pi10 = square root wall area of a hypothetical airway with 10-mm internal perimeter.

Each row is a separate model.

Logistic regression with OR, 95% CI.

Linear regression.

Linear mixed model with beta coefficient (β), SE.

Adjusted for pack-years of smoking.

Adjusted for sex, age, race.

Adjusted for FEV1 % predicted.

Adjusted for current smoking.

Adjusted for height.

Adjusted for scanner model, BMI.

Data available for only a portion of the population.

Table 3.

Disease Progression in Childhood Asthma

| Variable | Childhood Asthma N = 323 |

No Childhood Asthma N = 4,563 |

Impact of Childhood Asthmaa |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | 95% CI | P Value | |||

| Development of COPD, No. (%)b,e,f | 27 (8) | 317 (7) | 1.22 | 0.80-1.81 | .34 |

| Development of oxygen requirement, No. (%)b.e.f | 23 (7) | 295 (6) | 1.26 | 0.78-1.92 | .31 |

| Development of chronic bronchitis, No. (%)b,e,f,h | 28 (9) | 359 (8) | 1.26 | 0.82-1.87 | .27 |

| Had a severe COPD exacerbation in prior y, No. (%)b,e,f,g,h | 52 (16) | 406 (9) | 1.41 | 1.00-1.96 | .04 |

| β | SE | P Value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of COPD exacerbations in prior y, mean (SD)c,e,f,g,h | 0.59 (1.08) | 0.29 (0.77) | 0.22 | 0.04 | < .001 |

| FEV1 postbronchodilator, % predicted, mean Δ (SD)d,e | –1.48 (12) | –1.98 (10) | 0.47 | 0.60 | .44 |

| FEV1 postbronchodilator, mL, mean Δ (SD)d,e,f,i | –168 (303) | –204 (284) | 32.10 | 16.61 | .05 |

| FVC postbronchodilator, % predicted, mean Δ (SD)d,e | –0.73 (13) | –2.15 (12) | Model does not converge | ||

| FVC postbronchodilator, mL, mean Δ (SD)d,e,f,i | –188 (432) | –252 (421) | 58.44 | 24.84 | .02 |

| St. George’s Respiratory Questionnaire score, mean Δ (SD)d,e,f,g | –2.22 (18) | 0.39 (15) | –2.40 | 0.88 | .01 |

| Modified Medical Research Council dyspnea scale, mean Δ (SD)d,e,f,g | –0.02 (1.26) | 0.07 (1.23) | –0.08 | 0.07 | .25 |

| 6-min walk distance in feet, mean Δ (SD)d,e,f,g | –151 (385) | –130 (360) | –27.21 | 20.93 | .19 |

| CT scan measuresk | |||||

| Emphysema progression | |||||

| PRM emphysema % at –950 HU, mean Δ (SD)d,e,f,h,j | 0.61 (4) | 0.68 (3) | –0.29 | 0.23 | .20 |

| Adjusted density, mean Δ (SD)d,e,f,h,j | –1.33 (12) | –0.72 (11) | 0.17 | 0.58 | .77 |

| Air trapping progression | |||||

| Gas trapping %, expiratory scan at –856 HU, mean Δ (SD)d,e,f,h,j | 1.19 (9) | 1.19 (9) | –0.78 | 0.60 | .20 |

| PRM functional small airway disease, mean Δ (SD)d,e,f,h,j | 0.97 (8) | 0.93 (7) | –0.41 | 0.51 | .42 |

| Airway thickening progression | |||||

| SRWA-Pi10 (SD), mean Δ (SD)d,e,f,h,j | 0.07 (0.33) | 0.04 (0.30) | 0.03 | 0.04 | .41 |

See Table 2 legend for expansion of abbreviations.

Each row is a separate model.

Logistic regression with OR, 95% CI.

Linear regression.

Linear mixed model with β, SE.

Adjusted for pack-years of smoking.

Adjusted for sex age, race.

Adjusted for FEV1 % predicted.

Adjusted for current smoking.

Adjusted for height.

Adjusted for scanner model, BMI.

Data available for only a portion of the population.

Table 4.

Disease Progression in ACO

| Variable | ACO N = 242 |

COPD N = 1,359 |

Impact of ACOa |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | 95% CI | P Value | |||

| Development of oxygen requirement, No. (%)b,e,f | 33 (14) | 207 (15) | 0.97 | 0.64-1.45 | .90 |

| Development of chronic bronchitis, No. (%)b,e,f,h | 24 (10) | 155 (11) | 0.90 | 0.55-1.42 | .67 |

| Had a severe COPD exacerbation in prior y, No. (%)b,e,f,g,h | 60 (25) | 237 (17) | 1.42 | 1.00-2.00 | .05 |

| β | SE | P Value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of COPD exacerbations in prior y, mean (SD)c,e,f,g,h | 0.81 (1.23) | 0.56 (1.03) | 0.20 | 0.07 | .006 |

| FEV1 postbronchodilator, % predicted, mean Δ (SD)d,e | –2.53 (11) | –2.64 (11) | 0.10 | 0.76 | .89 |

| FEV1 postbronchodilator, mL, mean Δ (SD)d,e,f,i | –160 (313) | –188 (306) | 22.70 | 21.73 | .30 |

| FVC postbronchodilator, % predicted, mean Δ (SD)d,e | –2.81 (14) | –3.69 (14) | 0.84 | 0.97 | .39 |

| FVC postbronchodilator, mL, mean Δ (SD)d,e,f,i | –239 (466) | –314 (506) | 65.68 | 35.85 | .07 |

| St. George’s Respiratory Questionnaire score, mean Δ (SD)d,e,f,g | –1.09 (17) | 1.84 (15) | –2.89 | 1.06 | .007 |

| Modified Medical Research Council dyspnea scale, mean Δ (SD)d,e,f,g | 0.09 (1.26) | 0.22 (1.29) | –0.13 | 0.09 | .16 |

| 6-min walk distance in feet, mean Δ (SD)d,e,f,g | –156 (356) | –189 (370) | 23.60 | 25.94 | .36 |

| CT scan measuresk | |||||

| Emphysema progression | |||||

| PRM emphysema % at –950 HU, mean Δ (SD)d,e,f,h,j | 1.14 (5) | 2.14 (5) | –0.97 | 0.41 | .02 |

| Adjusted density, mean Δ (SD)d,e,f,h,j | –2.05 (11) | –3.32 (11) | 1.27 | 0.67 | .06 |

| Air trapping progression | |||||

| Gas trapping %, expiratory scan at –856 HU, mean Δ (SD)d,e,f,h,j | 1.57 (11) | 3.72 (10) | –2.19 | 0.89 | .01 |

| PRM functional small airway disease, mean Δ (SD)d,e,f,h,j | 0.96 (9) | 2.12 (8) | –1.20 | 0.77 | .12 |

| Airway thickening progression | |||||

| SRWA-Pi10 (SD), mean Δ (SD)d,e,f,h,j | 0.08 (0.36) | 0.03 (0.34) | 0.04 | 0.06 | .54 |

ACO = asthma-COPD overlap. See Table 2 legend for expansion of other abbreviations.

Each row is a separate model.

Logistic regression with OR, 95% CI.

Linear regression.

Linear mixed model with β, SE.

Adjusted for pack-years of smoking.

Adjusted for sex, age, race.

Adjusted for FEV1 % predicted.

Adjusted for current smoking.

Adjusted for height.

Adjusted for scanner model, BMI.

Data available for only a portion of the population.

To assess an association with COPD exacerbations, a sensitivity analysis was performed in only the subset of subjects who had GOLD stage 2 to 4 COPD at the time of initial enrollment. Exacerbation severity, frequency, and rate of lung function decline were compared independently in subjects with COPD who had childhood pneumonia and those who did not, as well as those who had childhood asthma and those who had not.

Results

Subject Classification and Characteristics

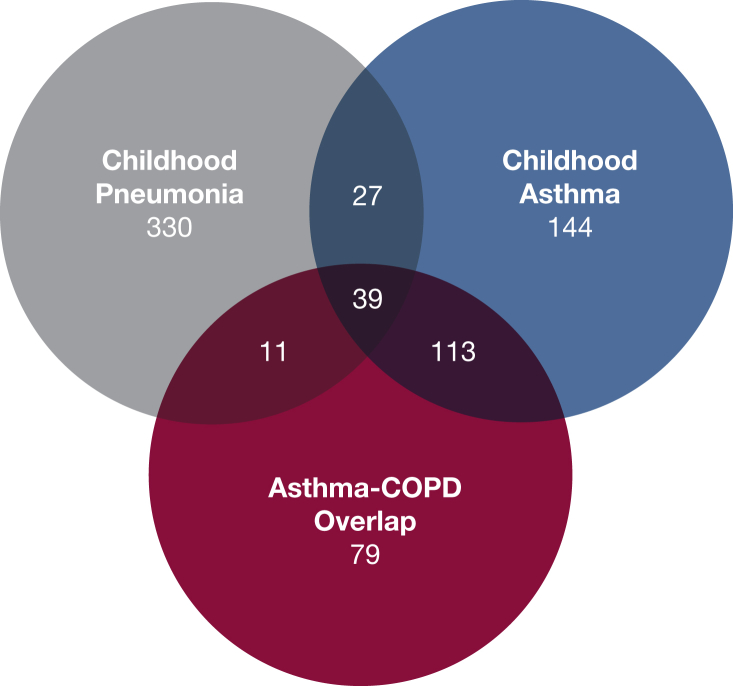

Of 10,199 enrolled adult smokers, 857 had childhood pneumonia (8.4%), 730 had childhood asthma (7.2%), and 569 had ACO (5.6%) (Table 1, e-Table 1). Five-year follow-up data on 4,915 subjects were examined; 19 subjects who had undergone interval lung transplantation or lung volume reduction surgery were excluded. Disease progression analysis in phase 2 included 407 subjects who had childhood pneumonia (47%), 323 subjects who had childhood asthma (44%), and 242 subjects with ACO (43%). Overlap between subject classifications can be seen in Figure 1. Subjects who had childhood pneumonia were older, more likely to be non-Hispanic white, and had a longer smoking history compared with subjects without childhood pneumonia. Subjects who had childhood asthma were younger and more likely to be African American than were those without childhood asthma. Subjects with ACO were more likely to be younger, female, and African American and have fewer pack-years of smoking than subjects with COPD but without ACO.

Figure 1.

Overlapping numbers of subjects as categorized for this study by history of childhood pneumonia, childhood asthma, or asthma-COPD overlap.

Mortality

Of 10,199 adult smokers enrolled in phase 1, mortality data were available for 8,901 (87%). Deceased subjects included 116 subjects who had childhood pneumonia (14%), 84 subjects who had childhood asthma (12%), and 103 subjects with ACO (18%) (e-Fig 1). There were no statistically significant differences in mortality among subjects with childhood pneumonia, childhood asthma, or ACO in the analysis adjusted for sex, age, race, FEV1, pack-years of smoking, and current smoking (P > 0.5 for all analyses).

Disease Progression

e-Table 1 shows univariate associations with childhood pneumonia, childhood asthma, and ACO. In multivariable models, childhood pneumonia was not associated with disease progression by lung function, clinical symptoms including severity and frequency of respiratory exacerbations, or chest CT scan measurements of emphysema and airway disease (Table 2).

Compared with those who did not have childhood asthma, subjects who had childhood asthma had an increased frequency of respiratory exacerbations (β = 0.22 exacerbations/y; P < .001) and increased odds of having had a severe exacerbation in the prior year (OR, 1.41; 95% CI, 1.00-1.96) (Table 3). Subjects who had childhood asthma showed less FVC decline (β = 58.44 mL; P = .02) and borderline significance for less FEV1 decline (β = 32.10 mL; P = .053). Subjects who had childhood asthma had a statistically significant but not clinically significant improvement in quality of life based on improvement in the SGRQ total score (β = –2.40 points; P = .01).21 On chest CT imaging, there were no differences in progression of emphysema and airway disease.

Compared with subjects with COPD only, subjects who had ACO had an increased frequency of exacerbations (β = 0.20 exacerbations/y; P = .006) and increased odds of a severe exacerbation (OR, 1.42; 95% CI, 1.00-2.00) (Table 4). They had a statistically but not clinically significant improvement in the SGRQ total score (β = –2.89 points; P = .007). There was no difference in the rate of decline in FEV1 or FVC. On chest CT images, subjects with ACO had less progression of emphysema and air trapping compared with subjects with COPD but no difference in the progression of airway wall thickening.

Sensitivity Analysis

There were 1,613 subjects with GOLD stage 2 to 4 COPD at enrollment who returned for 5-year follow-up. Among subjects with COPD, a history of childhood pneumonia was associated with increased frequency of respiratory exacerbations (β = 0.17; P = .04) when compared with subjects without a history of childhood pneumonia (e-Table 2); there was no significant increase in severe exacerbations or the rate of lung function decline. Subjects with COPD who had childhood asthma did not have increased frequency or severity of respiratory exacerbations when compared with those who did not have childhood asthma; there was an association with a slower rate of decline in FVC (β = 91.64 mL; P = .04).

Discussion

This investigation used 5-year follow-up data from 4,915 adult smokers to examine disease activity and progression independently in those who had childhood pneumonia or childhood asthma and those with ACO. Childhood asthma and ACO were associated with increased disease activity, with more frequent and severe exacerbations, but not with disease progression defined by lung function decline and chest CT changes. Subjects who had childhood asthma had less lung function decline, and subjects with ACO had less progression of CT emphysema and air trapping. Childhood pneumonia was associated with increased respiratory exacerbations among COPD subjects, with no increase in the rate of lung function decline.

We have previously established that in adult smokers from the COPDGene Study, early-life respiratory diseases are associated with reduced lung function and COPD.1, 8, 9, 18 Childhood pneumonia was associated with increased odds of COPD developing (OR, 1.40; 95% CI, 1.17-1.66), with the greatest risk among those who had asthma and pneumonia in childhood (OR, 1.85; 95% CI, 1.10-3.18).1 Childhood asthma was associated with smaller segmental airways, which was a risk for decreased FEV1 and chronic airflow obstruction.9 Subjects with ACO, compared with those with COPD alone, were younger, with lower lifetime smoking intensity and increased exacerbation frequency.8, 18

Other cohorts have shown that asthma and wheezy bronchitis are associated with COPD risk.22 In the Childhood Asthma Management Program, 11% of 1,041 participants met spirometric criteria for COPD by age 30 years, and analysis of lung growth trajectories showed a subset with reduced lung growth.5 The Aberdeen WHEASE cohort followed 330 subjects to age 61 years, showing that childhood asthma and wheeze were associated with COPD development.23 The Melbourne Asthma Cohort found that childhood asthma conferred a 32-fold adjusted odds of COPD developing. In 45-year follow-up among 1,389 Tasmanian children, low childhood lung function was associated with COPD and ACO.24 These associations are likely due to reduced lung growth in patients with childhood respiratory disease causing a decrease in maximally attained lifetime FEV1 and an increasing probability that natural decline in lung function will lead to diagnostic levels of COPD. This concept is supported by prior descriptions of lung function trajectories, which showed that current and former smokers with low FEV1 in early adulthood can acquire COPD based only on natural lung function decline.7

In this study, subjects who had childhood asthma and subjects with ACO were “frequent exacerbators” yet did not have a significantly increased rate of lung function decline or emphysema progression at 5-year follow-up. This is contrary to previous descriptions of frequent exacerbators in COPDGene in which there was an association between frequent exacerbations and excess FEV1 decline.25 This difference is likely due to the fact that in our current study we examined frequent exacerbators who had asthma in early life. Subjects with asthma may have different drivers of exacerbations than those in usual subjects with COPD, as well as a slower rate of lung function decline. Our current investigation of disease progression in patients with asthma supports work from the European Community Respiratory Health survey examining 218 subjects with ACO and showing that they had less FEV1 decline than did subjects with COPD at 4- to 12-year follow-up but that they had higher hospitalization rates.26 Similarly, in 55 subjects from an Australian cohort, ACO was not associated with longitudinal lung function decline over 4 years.27

This study expands our understanding of the natural history of COPD in smokers who had childhood respiratory disease and highlights the significance of asthma in early life, which is a known risk factor for the development of COPD. Our study reveals that disease progression is distinctly different for these subjects, who experience more frequent and severe exacerbations but without a significantly increased rate of lung function decline. In fact, these subjects appeared to be protected from a decline in lung function (in those who had childhood asthma) or progression of emphysema (in those with ACO). In a sensitivity analysis looking only at subjects with COPD, childhood pneumonia was associated with more frequent exacerbations without any difference in rate of lung function decline, and childhood asthma was associated with less FVC decline.

This study is limited by the use of a self-reported history of pneumonia and asthma. Ideally, medical records of diagnoses would be available; however, in this large study of adult subjects, this would have required childhood records, which was not feasible. Self-reported diagnosis has been shown to be effective at revealing meaningful subsets of subjects with early-life respiratory disease in our prior investigations in this cohort, which have included sensitivity analysis for recall bias.1, 8, 9, 28 It would be optimal to examine disease progression in nonsmokers; however, this COPDGene investigation did not include data on nonsmokers. This is an important area for future investigation.

This study examines disease progression at 5-year follow-up in approximately half of the original cohort. A limitation in this population with significant morbidity is a concern about selection bias. Ideally, we would include all original subjects in longitudinal analysis. Of the original 10,199 subjects enrolled, 6,056 have been accounted for (59%), including 1,141 deaths and 4,915 subjects with phase 2 data. Additional efforts are ongoing to bring back more subjects. The CT analysis is limited by data being available only for a subset of phase 2 subjects, which particularly affected SRWA-Pi10 data.

Conclusions

We demonstrate that among a population of adult smokers, asthma in early life results in more active respiratory disease, with increased frequency and severity of exacerbations but without an increased rate of lung function decline or disease progression on chest CT scans.22 Early-life respiratory diseases are known risk factors for the development of COPD.1, 2, 3, 4, 5 COPD in these populations is likely due to lung development progressing along a reduced lung growth trajectory, with maximal expected FEV1 never being achieved. Thus, these subjects are at risk for reaching a level of COPD even with only typical lung function decline associated with aging. This investigation elucidates the expected course of COPD in at-risk populations, showing that early-life respiratory diseases are risk factors for active disease without lung function decline. This supports the idea that there is an alternative pathway to reach COPD in smokers with early-life respiratory disease, suggesting a subtype of COPD with a different mechanism of reduced FEV1. These subjects with asthma additionally may have different drivers of respiratory exacerbations, and a better understanding of this relationship could promote different therapeutic considerations, allowing increased precision in COPD treatment.

Acknowledgments

Author contributions: C. P. H. is the guarantor of the paper and is responsible for the data and study design and confirms that the study objectives and procedures are honestly disclosed. Moreover, he has reviewed study execution data and confirms that procedures were followed to an extent that convinces all authors that the results are valid and generalizable to a population similar to that enrolled in this study. L. P. H., M. E. H., W. Q., D. A. L., M. J. S., E. J. v. B., J. D. C., E. K. S., and C. P. H. contributed to data analysis and interpretation, critical revision of the article, and final approval of the version to be published; they all agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work. L. P. H., M. E. H., D. A. L., M. J .S ., J. D .C., E. K. S., and C. P. H. contributed to the study conception and design. J. D. C., E. K. S., and C. P. H. contributed to the acquisition of data. L. P. H. and C. P. H. contributed to drafting of the submitted article.

Financial/nonfinancial disclosures: The authors have reported to CHEST the following: C. P. H. reports personal fees from AstraZeneca, grants from Boehringer Ingelheim, personal fees from Mylan, and personal fees from Concert Pharmaceuticals outside the submitted work. D. A. L. reports personal fees from Parexel, research support from Veracyte, personal fees from Boehringer Ingelheim, and personal fees from Genentech/Roche. E. J. v. B. receives research support unrelated to this manuscript from Siemens Healthineers, GE Healthcare; he is a founder/owner of QCTS, Ltd. and a consultant for Holoxica, Ltd., Imbio, Inc., and Mentholatum, Ltd. In the past 3 years, E. K. S. has received honoraria from Novartis for Continuing Medical Education Seminars and grant and travel support from GlaxoSmithKline unrelated to this manuscript. M. E. H. works in the Clinical Discovery Unit at AstraZeneca. None declared (J. D. C., L. P. H., M. J. S., W. Q.).

Role of sponsors: The sponsor had no role in the design of the study, the collection and analysis of the data, or the preparation of the manuscript. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Heart, Lung, And Blood Institute or the National Institutes of Health.

*Collaborating investigators for the COPDGene Study: Administrative Center: James D. Crapo, MD (principle investigator]); Barry J. Make, MD; Elizabeth A. Regan, MD, PhD; Edwin K. Silverman, MD, PhD (principle investigator). Genetic Analysis Center: Terri Beaty, PhD; Ferdouse Begum, PhD; Adel R. Boueiz, MD; Robert Busch, MD; Peter J. Castaldi, MD, MSc; Michael Cho, MD; Dawn L. DeMeo, MD, MPH; Marilyn G. Foreman, MD, MS; Eitan Halper-Stromberg; Nadia N. Hansel, MD, MPH; Megan E. Hardin, MD; Lystra P. Hayden, MD, MMSc; Craig P. Hersh, MD, MPH; Jacqueline Hetmanski, MS, MPH; Brian D. Hobbs, MD; John E. Hokanson, MPH, PhD; Nan Laird, PhD; Christoph Lange, PhD; Sharon M. Lutz, PhD; Merry-Lynn McDonald, PhD; Margaret M. Parker, PhD; Dandi Qiao, PhD; Elizabeth A. Regan, MD, PhD; Stephanie Santorico, PhD; Edwin K. Silverman, MD, PhD; Emily S. Wan, MD. Sungho Won Imaging Center: Mustafa Al Qaisi, MD; Harvey O. Coxson, PhD; Teresa Gray; MeiLan K. Han, MD, MS; Eric A. Hoffman, PhD; Stephen Humphries, PhD; Francine L. Jacobson, MD, MPH; Philip F. Judy, PhD; Ella A. Kazerooni, MD; Alex Kluiber; David A. Lynch, MB; John D. Newell, Jr, MD; Elizabeth A. Regan, MD, PhD; James C. Ross, PhD; Raul San Jose Estepar, PhD; Joyce Schroeder, MD; Jered Sieren; Douglas Stinson; Berend C. Stoel, PhD; Juerg Tschirren, PhD; Edwin Van Beek, MD, PhD; Bram van Ginneken, PhD; Eva van Rikxoort, PhD; George Washko, MD; Carla G. Wilson, MS. PFT QA Center, Salt Lake City, UT: Robert Jensen, PhD. Data Coordinating Center and Biostatistics, National Jewish Health, Denver, CO: Jim Crooks, PhD; Douglas Everett, PhD; Camille Moore, PhD; Matt Strand, PhD; Carla G. Wilson, MS. Epidemiology Core, University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus, Aurora, CO: John E. Hokanson, MPH, PhD; John Hughes, PhD; Gregory Kinney, MPH, PhD; Sharon M. Lutz, PhD; Katherine Pratte, MSPH; Kendra A. Young, PhD.

COPDGene Study Clinical Centers: Ann Arbor VA: Jeffrey L. Curtis, MD; Carlos H. Martinez, MD, MPH; Perry G. Pernicano, MD. Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, TX: Philip Alapat, MD; Mustafa Atik, MD; Venkata Bandi, MD; Aladin Boriek, PhD; Kalpatha Guntupalli, MD; Elizabeth Guy, MD; Nicola Hanania, MD, MS; Arun Nachiappan, MD; Amit Parulekar, MD. Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, MA: Dawn L. DeMeo, MD, MPH; Craig Hersh, MD, MPH; Francine L. Jacobson, MD, MPH; George Washko, MD. Columbia University, New York, NY: John Austin, MD; R. Graham Barr, MD, DrPH; Belinda D’Souza, MD; Gregory D.N. Pearson, MD; Anna Rozenshtein, MD, MPH; Byron Thomashow, MD. Duke University Medical Center, Durham, NC: Neil MacIntyre, Jr., MD; H. Page McAdams, MD; Lacey Washington, MD. HealthPartners Research Institute, Minneapolis, MN: Charlene McEvoy, MD, MPH; Joseph Tashjian, MD. Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, MD: Robert Brown, MD; Nadia N. Hansel, MD, MPH; Karen Horton, MD; Allison Lambert, MD, MHS; Nirupama Putcha, MD, MHS; Robert Wise, MD. Los Angeles Biomedical Research Institute at Harbor UCLA Medical Center, Torrance, CA: Alessandra Adami, PhD; Matthew Budoff, MD; Richard Casaburi, PhD, MD; Hans Fischer, MD; Janos Porszasz, MD, PhD; Harry Rossiter, PhD; William Stringer, MD. Michael E. DeBakey VAMC, Houston, TX: Charlie Lan, DO Amir Sharafkhaneh, MD, PhD. Minneapolis VA: Brian Bell, MD; Christine Wendt, MD. Morehouse School of Medicine, Atlanta, GA: Eugene Berkowitz, MD, PhD; Marilyn G. Foreman, MD, MS; Gloria Westney, MD, MS. National Jewish Health, Denver, CO: Russell Bowler, MD, PhD; David A. Lynch, MB. Reliant Medical Group, Worcester, MA: David Pace; MD Richard Rosiello, MD. Temple University, Philadelphia, PA: David Ciccolella, MD; Francis Cordova, MD; Gerard Criner, MD; Chandra Dass, MD; Gilbert D’Alonzo, DO; Parag Desai, MD; Michael Jacobs, PharmD; Steven Kelsen, MD, PhD; Victor Kim, MD; A. James Mamary, MD; Nathaniel Marchetti, DO; Aditi Satti, MD; Kartik Shenoy, MD; Robert M. Steiner, MD; Alex Swift, MD; Irene Swift, MD; Maria Elena Vega-Sanchez, MD. University of Alabama, Birmingham, AL: William Bailey, MD; Surya Bhatt, MD; Mark Dransfield, MD; Anand Iyer, MD; Hrudaya Nath, MD; J. Michael Wells, MD. University of California, San Diego, CA: Paul Friedman, MD; Joe Ramsdell, MD; Xavier Soler, MD, PhD; Andrew Yen, MD. University of Iowa, Iowa City, IA: Alejandro P. Comellas, MD; John Newell, Jr, MD; Brad Thompson, MD. University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI: MeiLan K. Han, MD, MS; Ella Kazerooni, MD; Carlos H. Martinez, MD, MPH. University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, MN: Tadashi Allen, MD; Abbie Begnaud, MD; Joanne Billings, MD. University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, PA: Jessica Bon, MD; Divay Chandra, MD, MSc; Carl Fuhrman, MD; Frank Sciurba, MD; Joel Weissfeld, MD, MPH. University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio, San Antonio, TX: Sandra Adams, MD; Antonio Anzueto, MD; Diego Maselli-Caceres, MD; Mario E. Ruiz, MD.

Additional information: The e-Figures, e-Tables, and e-Appendix can be found in the Supplemental Materials section of the online article.

Footnotes

FUNDING/SUPPORT: This work was supported by National Institutes of Health (NIH) [Grants K12HL120004 (E. K. S.), R01HL130512 (C. P. H.), R01HL125583 (C. P. H.), P01HL105339 (E. K. S.), R01HL089897 (J. D. C.), and R01HL089856 (E. K. S.)]. The COPDGene project is also supported by the COPD Foundation through contributions made to an industry advisory board composed of AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, GlaxoSmithKline, Novartis, Pfizer, Siemens, and Sunovion. Neither the NIH nor the Industry Advisory Board had a role in the study design, data collection, data analysis, interpretation of the data, writing of the report, or the decision to submit the paper for publication. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute or the NIH.

Contributor Information

Lystra P. Hayden, Email: lystra.hayden@childrens.harvard.edu.

COPDGene Investigators∗:

James D. Crapo, Barry J. Make, Elizabeth A. Regan, Edwin K. Silverman, Terri Beaty, Ferdouse Begum, Adel R. Boueiz, Robert Busch, Peter J. Castaldi, Michael Cho, Dawn L. DeMeo, Marilyn G. Foreman, Eitan Halper-Stromberg, Nadia N. Hansel, Megan E. Hardin, Lystra P. Hayden, Craig P. Hersh, Jacqueline Hetmanski, Brian D. Hobbs, John E. Hokanson, Nan Laird, Christoph Lange, Sharon M. Lutz, Merry-Lynn McDonald, Margaret M. Parker, Dandi Qiao, Elizabeth A. Regan, Stephanie Santorico, Edwin K. Silverman, Emily S. Wan, Mustafa Al Qaisi, Harvey O. Coxson, Teresa Gray, MeiLan K. Han, Eric A. Hoffman, Stephen Humphries, Francine L. Jacobson, Philip F. Judy, Ella A. Kazerooni, Alex Kluiber, David A. Lynch, John D. Newell, Jr., Elizabeth A. Regan, James C. Ross, Raul San Jose Estepar, Joyce Schroeder, Jered Sieren, Douglas Stinson, Berend C. Stoel, Juerg Tschirren, Edwin Van Beek, Bram van Ginneken, Eva van Rikxoort, George Washko, Carla G. Wilson, Robert Jensen, Jim Crooks, Douglas Everett, Camille Moore, Matt Strand, Carla G. Wilson, John E. Hokanson, John Hughes, Gregory Kinney, Sharon M. Lutz, Katherine Pratte, and Kendra A. Young

Supplementary Data

References

- 1.Hayden L.P., Hobbs B.D., Cohen R.T. Childhood pneumonia increases risk for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: The COPDGene study. Respir Res. 2015;161(1):115. doi: 10.1186/s12931-015-0273-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Svanes C., Sunyer J., Plana E. Early life origins of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Thorax. 2010;651(1):14–20. doi: 10.1136/thx.2008.112136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Martinez F.D. Early-life origins of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(9):871–878. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1603287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tai A., Tran H., Roberts M., Clarke N., Wilson J., Robertson C.F. The association between childhood asthma and adult chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Thorax. 2014;69(9):805–810. doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2013-204815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McGeachie M.J., Yates K.P., Zhou X. Patterns of growth and decline in lung function in persistent childhood asthma. N Engl J Med. 2016;374(19):1842–1852. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1513737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Postma D.S., Rabe K.F. The asthma-COPD overlap syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2015;373(13):1241–1249. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1411863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lange P., Celli B., Agusti A. Lung-function trajectories leading to chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. N Engl J Med. 2015;373(2):111–122. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1411532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hardin M., Cho M., McDonald M.L. The clinical and genetic features of COPD-asthma overlap syndrome. Eur Respir J. 2014;44(2):341–350. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00216013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Diaz A.A., Hardin M.E., Come C.E. Childhood-onset asthma in smokers. Association between CT measures of airway size, lung function, and chronic airflow obstruction. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2014;11(9):1371–1378. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201403-095OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Regan E.A., Hokanson J.E., Murphy J.R. Genetic epidemiology of COPD (COPDGene) study design. COPD. 2010;7(1):32–43. doi: 10.3109/15412550903499522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.COPDGene. Phase 1 study documents. http://www.copdgene.org/phase-1-study-documents. Accessed March 13, 2015.

- 12.Ferris BG. Epidemiology standardization project (American Thoracic Society). Am Rev Respir Dis. 118(6 pt 2):1-120. [PubMed]

- 13.Brooks S. Surveillance for respiratory hazards. ATS News. 1982;8:12–16. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jones P.W., Quirk F.H., Baveystock C.M. The St George's Respiratory Questionnaire. Respir Med. 1991;85(suppl B):25–31. doi: 10.1016/s0954-6111(06)80166-6. discussion 33-27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bhatt S.P., Soler X., Wang X. Association between functional small airway disease and FEV1 decline in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2016;194(2):178–184. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201511-2219OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nakano Y., Wong J.C., de Jong P.A. The prediction of small airway dimensions using computed tomography. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2005;171(2):142–146. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200407-874OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hoffman EA, Gnanaprakasam D, Gupta KB, Hoford JD, Kugelmass SD, Kulawiec RS. Vida: An environment for multidimensional image display and analysis. 1992(1660):694-711.

- 18.Hardin M., Silverman E.K., Barr R.G. The clinical features of the overlap between COPD and asthma. Respir Res. 2011;12:127. doi: 10.1186/1465-9921-12-127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sin D.D., Miravitlles M., Mannino D.M. What is asthma-COPD overlap syndrome? Towards a consensus definition from a round table discussion. Eur Respir J. 2016;48(3):664–673. doi: 10.1183/13993003.00436-2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rabe K.F., Hurd S., Anzueto A. Global strategy for the diagnosis, management, and prevention of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: Gold executive summary. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2007;176(6):532–555. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200703-456SO. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jones P.W. St. George's respiratory questionnaire: MCID. COPD. 2005;2(1):75–79. doi: 10.1081/copd-200050513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.McGeachie M.J. Childhood asthma is a risk factor for the development of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol. 2017;17(2):104–109. doi: 10.1097/ACI.0000000000000348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tagiyeva N., Devereux G., Fielding S., Turner S., Douglas G. Outcomes of childhood asthma and wheezy bronchitis. A 50-year cohort study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2016;193(1):23–30. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201505-0870OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bui D.S., Burgess J.A., Lowe A.J. Childhood lung function predicts adult chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and asthma-chronic obstructive pulmonary disease overlap syndrome. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2017;196(1):39–46. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201606-1272OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dransfield M.T., Kunisaki K.M., Strand M.J. Acute exacerbations and lung function loss in smokers with and without chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2017;195(3):324–330. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201605-1014OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.de Marco R., Marcon A., Rossi A. Asthma, COPD and overlap syndrome: a longitudinal study in young European adults. Eur Respir J. 2015;46(3):671–679. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00008615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fu J.J., Gibson P.G., Simpson J.L., McDonald V.M. Longitudinal changes in clinical outcomes in older patients with asthma, COPD and asthma-COPD overlap syndrome. Respiration. 2014;87(1):63–74. doi: 10.1159/000352053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hayden L.P., Cho M.H., McDonald M.N. Susceptibility to childhood pneumonia: a genome-wide analysis. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2017;56(1):20–28. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2016-0101OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.