Abstract

Gut microbiota has been recognized to play a beneficial role in honey bees (Apis mellifera). Present study was designed to characterize the gut bacterial flora of honey bees in north-west Pakistan. Total 150 aerobic and facultative anaerobic bacteria from guts of 45 worker bees were characterized using biochemical assays and 16S rDNA sequencing followed by bioinformatics analysis. The gut isolates were classified into three bacterial phyla of Firmicutes (60%), Proteobacteria (26%) and Actinobacteria (14%). Most of the isolates belonged to genera and families of Staphylococcus, Bacillus, Enterococcus, Ochrobactrum, Sphingomonas, Ralstonia, Enterobacteriaceae, Corynebacterium and Micrococcineae. Many of these bacteria were tolerant to acidic environments and fermented sugars, hence considered beneficial gut inhabitants and involved the maintenance of a healthy microbiota. However, several opportunistic commensals that proliferate in the hive environment including members Staphylococcus haemolyticus group and Sphingomonas paucimobilis were also identified. This is the first report on bee gut microbiota from north-west Pakistan geographically situated at the crossroads of Indian subcontinent and central Asia.

Keywords: Apis mellifera, Alimentary canal, Microbiota, Insect physiology, Pollinator

1. Introduction

As a pollinator, honey bee has a prominent role in sustainable agriculture in addition to production of honey and other natural products (Klein et al., 2007, Potts et al., 2010). Compared to other bee species, honey bees have been reported to increase the yield in animal pollinated crops which account for 35% of the global food production (Genersch, 2010, Klein et al., 2007). Hence, research related to physiology and pathology of honey bees in particular Apis mellifera has attracted a lot of attention (Muli et al., 2014).

Numerous causes of severe honey bee colony losses have been proposed, including pesticides toxicity (Desneux et al., 2007), poor nutrition (Brodschneider and Crailsheim, 2010) and genetic diversity (Mattila and Seeley, 2007). A high load of parasites and microbial pathogens, especially bacteria strongly connected with the disappearing of bee population (Core et al., 2012, Di Prisco et al., 2013, Olofsson and Vásquez, 2008). Therefore, characterization of bee gut microbiome can provide valuable insight about of parasites and bacterial pathogens.

Bacteriological analysis along with molecular techniques based on 16S rRNA sequences precisely characterize insects gut bacterial flora (Prabhakar et al., 2013, Ahn et al., 2012). The composition of bacterial assemblage in the digestive tract of honey bee A. mellifera is relatively simple compared with other gut-associated communities (Babendreier et al., 2007, Cox-Foster et al., 2007, Engel and Moran, 2013). A distinctive set of bacteria including Firmicutes, Actinobacteria, α- and γ-proteobacteria found in the honey bee alimentary canal has been assessed by using Sanger as well as next generation sequencing techniques (Engel et al., 2012, Evans and Schwarz, 2011, Jeyaprakash et al., 2003, Li et al., 2012, Martinson et al., 2011).

Pakistan is located at the north-western frontier of the distribution range of the honey bees A. cerana, A. dorsata and A. florae. However, due to the low honey yields of eastern honey bees, commercial beekeepers in Pakistan use western honey bee A. mellifera since late 1980s (Waghchoure-Camphor and Martin, 2008). In this study, we characterized the aerobic and facultative anaerobic bacteria isolated from alimentary canal of A. mellifera from honey producing areas in north-west Pakistan.

2. Material and methods

2.1. Sample collection and dissection of the bees

In order to study the cultivable honey bee gut bacteria, 45 worker honey bees (A. mellifera) were collected from the bee farms located in cruciferous vegetation in districts of Kohat, Karak and Bannu in north west Pakistan. After collection, live bees were transported to the laboratory in the small cages containing sugar powder followed by storage at −20 °C until processing. Before dissection, whole bees were washed in 95% ethanol and complete alimentary canals of bees were aseptically dissected by clipping the stinger with sterile forceps. The dissected guts were macerated with sterile dissection scissors in 0.8% NaCl solution and immediately stored at −20 °C.

2.2. Culturing of bacteria

From the preserved bee gut samples, different dilutions (i.e. 1/10, 1/100 and 1/1000) were made and 100 μl aliquots of the diluted sample were inoculated in LB agar plates and incubated for 24–48 h at 37 °C. The separated colonies in master plates were sub-cultured in LB agar plates and incubated at 37 °C and the morphology of isolated colonies in subculture plates was noted.

2.3. Biochemical tests

Various biochemical tests were performed including Coagulase test, Oxidase test, Urease test, Lactose fermentation test, and hydrogen sulfite production test etc. for the identification of bacterial isolates with the help of Bergey’s Manual and API 20 NE identification system for non-fastidious, non-enteric Gram negative rods (Biomerieux, France).

2.4. Colony PCR and DNA sequencing

Isolated bacterial colony was subjected to amplification of the 16S rDNA gene according to Khan et al. (2014). The forward primer 5′-GGCTCAGAACGAACGCTGGCGGC-3′ and the reverse primer 5′-CCCACTGCTGCCTCCCGTAGGAGT-3′ were used. These primers are highly specific for conserved regions of bacterial 16S ribosomal DNA. PCR product (10 μl) was subjected to electrophoresis and 40 μl was purified with PCR clean up kit (Invitrogen Inc. USA). The DNA estimation was carried by using Qubit dsDNA Hs assay kit with Qubit 2.0 Fluorometer (Invitrogen, USA). The PCR products were sequenced using Big Dye Terminator kit and Genetic Analyzer ABI 377 (Applied Biosystems Inc., USA).

2.5. Sequence analysis

The resultant sequencing data was analyzed by Sequence Scanner v1.0 (Applied Biosystems Inc., USA). The 16S rDNA sequence of each bacterial isolate was compared using BLAST (Camacho et al., 2008) against ‘16S ribosomal RNA sequences (Bacteria and Archaea) database’ (a subdivision of GenBank) and Ribosomal Database Project (Cole et al., 2014).

3. Results and discussion

Honey production is a profitable small enterprise in Khyber Pakhtoonkhwa province in north-west of Pakistan. Currently ∼7000 beekeepers are involved in bee business in Pakistan with a total of 300,000 colonies of A. mellifera which produce ∼7500 metric tons of honey each year (Waghchoure-Camphor and Martin, 2008). Due to importance of gut bacteria in the development, nutrition and immunity of honey bees, we carried out an analysis of gut bacteria in worker bees in different apiaries in north-west Pakistan.

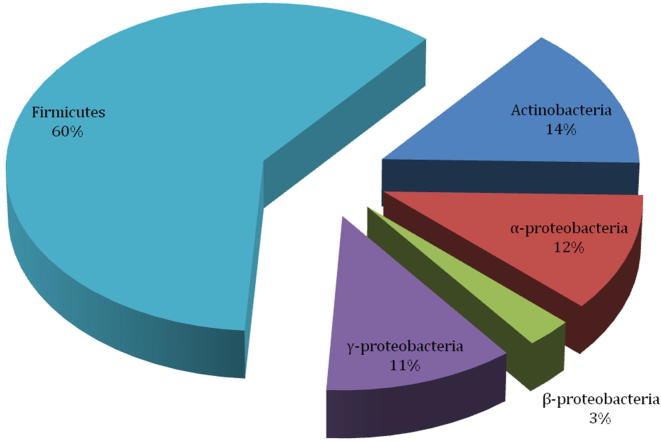

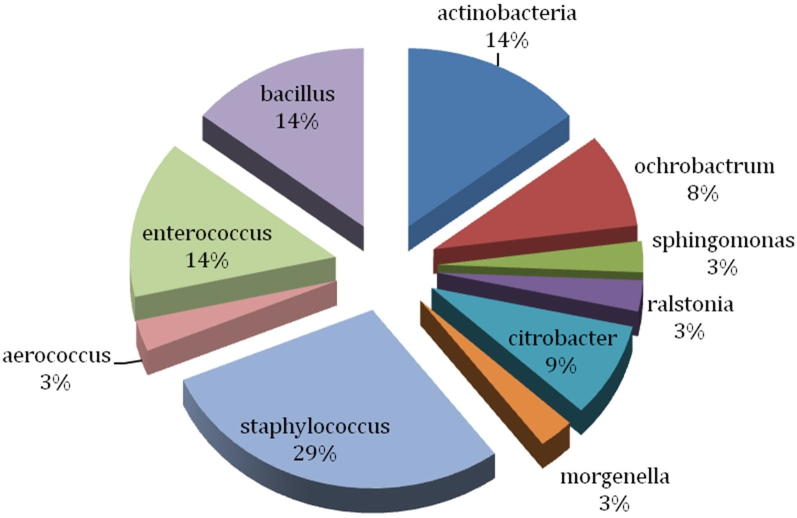

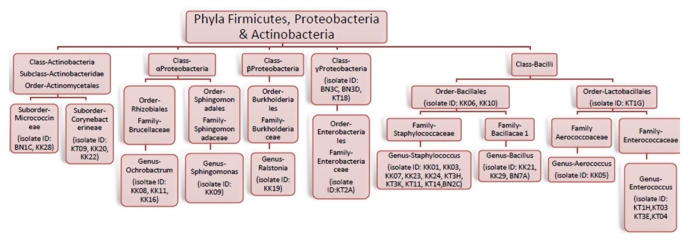

We isolated 150 aerobic and facultative anaerobic bacteria from guts of 45 worker A. mellifera collected from different apiaries located in cruciferous vegetation in honey producing districts of Khyber Pakhtoonkhwa (i.e. Kohat, Karak and Banuu) in north-west Pakistan. Based on colony morphology and other bacteriological characteristics, 100 bacterial isolates were subjected to 16S ribosomal DNA (rDNA) amplification followed by sequencing. Consequently, 77 sequences of 16S rDNA were obtained and analyzed by BLAST (Camacho et al., 2008) and Ribosomal Database Project (Cole et al., 2014). In general agreement with previous studies (Martinson et al., 2011, Jeyaprakash et al., 2003, Li et al., 2012, Ahn et al., 2012, Prabhakar et al., 2013), these sequence analyses approaches classified isolated gut bacteria into three phyla i.e. Firmicutes (60%), Proteobacteria (26%) and Actinobacteria (14%) (Fig. 1). Among Firmicutes, most of the isolates belonged to genera Staphylococcus, Bacillus and Enterococcus (Fig. 2). Members of family Enterobacteriaceae and following genera belonging to α-, β- and γ-Proteobacteria were also found i.e. Ochrobactrum, Sphingomonas, and Ralstonia (Fig. 2). Several actinobacterial isolates were classified in suborders of Corynebacterium and Micrococcineae. Hence culture based method adopted during this study revealed important members of “core” bacterial community present in alimentary canals of honey bees present in apiaries located in north-west of Pakistan (Fig. 3).

Fig. 1.

Phyla-wise classification of honeybee gut bacteria obtained during the present study.

Fig. 2.

Genera-wise classification of honeybee gut bacteria obtained during the present study.

Fig. 3.

Ribosomal Database Project based taxonomy of bacteria isolated from honeybee gut during the present study. Codes of representative isolates are given in parentheses.

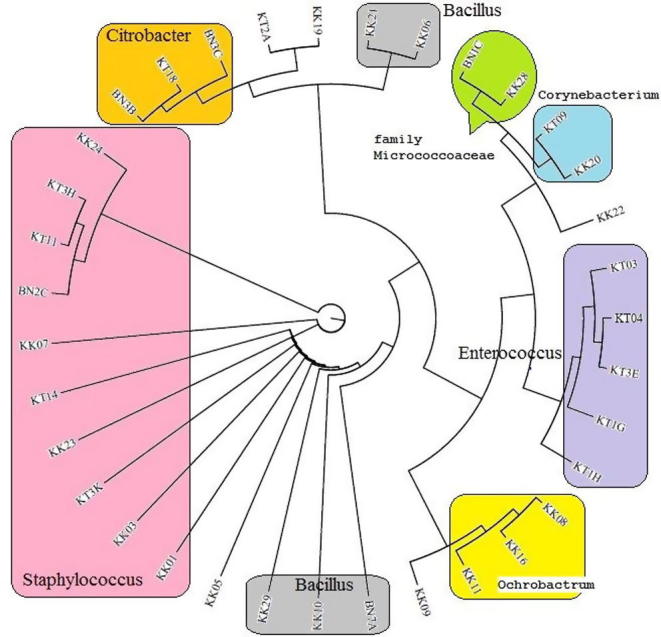

The phylogenetic tree of the partial 16S rDNA gene sequences of the bacterial isolates from the gut of honey bees showed relatedness among the bacteria when aligned with reference strains in GenBank (Fig. 4), which revealed that the bacterial population in the gut of honey bee foragers in North West Pakistan was diverse, including the phyla Firmicutes, Actinobacteria, and alpha-, beta-, and gamma-proteobacteria. The richness of these bacterial assemblages suggests their ecological importance. For instance, the abundance of one representative of Staphylococcus was estimated at 29% of the total microbial gut samples analyzed. Additionally, most of the 16S rDNA gene sequences were found very comparable to the sequences isolated from Apis sp that were already deposited in the NCBI database (Khan et al., 2017, Yoshiyama and Kimura, 2009, Martinson et al., 2012, Kacaniova et al., 2004)

Fig. 4.

Phylogenetic dendrogram of the 16S rDNA partial gene sequences of gut bacteria isolated from honey bees (Apis mellifera) in North West Pakistan. Groups (same genera) are shown in Color division. The tree was constructed using MEGA (V 6.), by the neighbor joining method. Bootstrap values (1000 replicates) expressed by most of all analysis.

Most of these bacteria were broadly classified as facultative anaerobes, tolerant of acidic environments and ferment sugars to produce lactic or acetic acid. These bacteria are considered beneficial gut inhabitants of humans and other animals and are involved in immunomodulation, interference with enteric pathogens and the maintenance of a healthy microbiota (Anderson et al., 2011). Some of the obligatory aerobic bacteria were adapted to highly acidic environments rich in sugar. As revealed by biochemical assays, many of these bacteria ferment sugars to produce lactic acid and various other end products, and several can reduce nitrate to nitrite suggesting a potential function in nitrogen metabolism within the gut. Beneficial honey bee bacterial strains are well represented in genomic databases, including 195 strains of Bacillus, 183 strains of Lactobacillus and 50 strains of Bifidobacterium (Anderson et al., 2011).

Bioinformatics analysis of 16S rDNA sequences in present dataset identified several opportunistic commensals that abound in the hive environment, but occur only sporadically within the honey bee gut. During this study, we frequently found Staphylococcal sequences. Careful sequence analysis showed occurrence of members of Staphylococcus haemolyticus group (i.e. S. devriesei, S. haemolyticus, S. hominis). Staphylococcal strains are rarely and/or briefly mentioned in available literature on bee gut microbiota. However, we recurrently encountered S. haemolyticus group strains originated from apiaries located in study area. S. haemolyticus is the second-most clinically isolated coagulase-negative Staphylococcus bacterium which is considered an important nosocomial pathogen (Vignaroli et al., 2006). Like other coagulase-negative staphylococci, S. hominis has been considered a presumptive and opportunistic pathogen which may occasionally cause infection in patients whose immune systems are compromised (Jiang et al., 2012). Moreover, Sphingomonas paucimobilis which was confidently classified by 16S rDNA sequences, has been reported as a cause of nosocomial infections (Ryan and Adley, 2010).

We identified several actinobacterial species during this study. These species included (a) Kocuria sp., previously isolated from air in China (Zhou et al., 2008); (b) Corynebacterium sp., widely distributed in nature and are mostly harmless (Collins et al., 2004) while Corynebacterium minutissimum is a causative agent of erythrasma (superficial skin infection) and other infections (Granok et al., 2002, Dalal and Likhi, 2008); and Micrococcus endophyticus, previously isolated from plant roots (Chen et al., 2009). Many Actinobacteria have been reported in beebread indicative of their long live in stored food (Anderson et al., 2013, Corby-Harris et al., 2014). The slow growth of Actinobacteria produce spores and the transmission of these spores between bee life stages and hive surroundings may occur on the body of individual honey bees (Corby-Harris et al., 2014).

Like ants, bees also belong to hymenoptera which are eusocial insects that survive in colonies with queen and thousands of worker bees which can forage large distances for collecting nectars and pollens and return to the hive. Hence their contact with various environments acts as a vector of diverse bacterial flora. More than fifty bacterial species from 31 genera have been found associated with different ants including Escherichia, Staphylococcus, Enterobacter, Pseudomonas, Bacillus, Streptococcus, and Klebsiella (Pesquero et al., 2012).

A number opportunistic pathogenic bacteria have already been reported from different insects including phytophagus insect aster leafhopper (Macrosteles quadrilineatus) in association with plants (Soto-Arias et al., 2014). Nectar has considered as an environmental bacterial reservoir. An array of bacterial species belongs to Firmicutes and Enterobacteriaceae are reported from nectar. Different bacillus species were frequently reported from the nectars of Acacia and Mesquite (Anderson et al., 2013). Acacia plants (Acacia Arabica, Acacia modesta and Acacia nilotica) are major bee plants in local flora of the study area (Marwat et al., 2013). Therefore, interaction of worker bees in the study areas nectar from the blossom of Acacia flowers catalyzed the transmission of environmental bacteria in the bee guts (Anderson et al., 2013, Fridman et al., 2012).

The possible routes of bacterial contamination in honey bee and its by-products are human, hive tools, sugar feeders, wind and dust. Beekeepers skin infections, fecal contamination and sneezing can introduce pathogenic microbes into the hive environment. Hence bee guts can act as a carrier of opportunistic bacterial pathogens. Additionally, due to political and economic disruption in the study area caused by the war against terrorism, most of the beekeepers were not able to keep their bees properly. Like in Europe, a remarkable decline in the bee hives was observed during the early 1990s caused by the Soviet collapse, rather than from widespread ecological factors (vanEngelsdorp and Meixner, 2010). The socio-economic status of beekeepers drastically changed with the ending of the Soviet Union. Likewise, many beekeepers in north-west Pakistan were engaged in static jobs like shops, and left the migration of bees from one floral area for the next due to current war events. Therefore, proper management of existing bee farms will increase the productivity and quality of honey and their byproducts.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgements

Authors are thankful to HEC and Gomal University D.I. Khan, Pakistan for providing financial support under ASIP and DRF respectively.

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of King Saud University.

References

- Anderson K.E., Sheehan T., Eckholm B., Mott B., Degrandi-Hoffman G. An emerging paradigm of colony health: microbial balance of the honey bee and hive (Apis mellifera) Insectes Soc. 2011;58:431–444. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson K.E., Sheehan T.H., Mott B.M., Maes P., Snyder L., Schwan M.R., Walton A., Jones B.M., Corby-Harris V. Microbial ecology of the hive and pollination landscape: bacterial associates from floral nectar, the alimentary tract and stored food of honey bees (Apis mellifera) PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e83125. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0083125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahn J.-H., Hong I.-P., Bok J.-I., Kim B.-Y., Song J., Hang-Yeon Weon H.-W. Pyrosequencing analysis of the bacterial communities in the guts of honey bees Apis cerana and Apis mellifera in Korea. J. Microbiol. 2012;50:735–745. doi: 10.1007/s12275-012-2188-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babendreier D., Joller D., Romeis J., Bigler F., Widmer F. Bacterial community structures in honeybee intestines and their response to two insecticidal proteins. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2007;59:600–610. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6941.2006.00249.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brodschneider R., Crailsheim K. Nutrition and health in honey bees. Apidologie. 2010;41:278–294. [Google Scholar]

- Camacho C., Coulouris G., Avagyan V., Ma N., Papadopoulos J., Bealer K., Madden T.L. BLAST+: architecture and applications. BMC Bioinformatics. 2008;10:421. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-10-421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen H.H., Zhao G.Z., Park D.J., Zhang Y.Q., Xu L.H., Lee J.C., Kim C.J., Li W.J. Micrococcus endophyticus sp. nov., isolated from surface-sterilized Aquilaria sinensis roots. Inter. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2009;59:1070–1075. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.006296-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cole, J.R., Wang, Q., Fish, J.A., Chai, B., McGarrell, D.M., Sun, Y., Brown, C.T., Porras-Alfaro, A., Kuske, C.R., Tiedje, J.M., 2014. Ribosomal database project: data and tools for high throughput rRNA analysis. Nucl. Acids Res. 42 (Database issue), D633–D642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Collins M.D., Hoyles L., Foster G., Falsen E. Corynebacterium caspium sp. nov., from a Caspian seal (Phoca caspica) Inter. J. Syst. Evolution. Microbiol. 2004;54:925–928. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.02950-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corby-Harris V., Maes P., Anderson K.E. The bacterial communities associated with honey bee (Apis mellifera) foragers. PLoS ONE. 2014;9:e95056. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0095056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Core A., Runckel C., Ivers J., Quock C., Siapno T., Denault S., Brown B., Derisi J., Smith C.D., Hafernik J. A new threat to honey bees, the parasitic phorid fly Apocephalus borealis. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e29639. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0029639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox-Foster D.L., Conlan S., Holmes E.C., Palacios G., Evans J.D., Moran N.A., Quan P.L., Briese T., Hornig M., Geiser D.M., Martinson V., vanEngelsdorp D., Kalkstein A.L., Drysdale A., Hui J., Zhai J., Cui L., Hutchison S.K., Simons J.F., Egholm M., Pettis J.S., Lipkin W.I. A metagenomic survey of microbes in honey bee colony collapse disorder. Science. 2007;318:283–287. doi: 10.1126/science.1146498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalal A., Likhi R. Corynebacterium minutissimum bacteremia and meningitis: a case report and review of literature. J. Infect. 2008;56:77–79. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2007.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desneux N., Decourtye A., Delpuech J.-M. The sublethal effects of pesticides on beneficial arthropods. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 2007;52:81–106. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ento.52.110405.091440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Prisco G., Cavaliere V., Annoscia D., Varricchio P., Caprio E., Nazzi F., Gargiulo G., Pennacchio F. Neonicotinoid clothianidin adversely affects insect immunity and promotes replication of a viral pathogen in honey bees. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. USA. 2013;110:18466–18471. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1314923110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engel P., Martinson V.G., Moran N.A. Functional diversity within the simple gut microbiota of the honey bee. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. USA. 2012;109:11002–11007. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1202970109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engel P., Moran N.A. Functional and evolutionary insights into the simple yet specific gut microbiota of the honey bee from metagenomic analysis. Gut Microbes. 2013;4:60–65. doi: 10.4161/gmic.22517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans J.D., Schwarz R.S. Bees brought to their knees: microbes affecting honey bee health. Trends Microbiol. 2011;19:614–620. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2011.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fridman S., Izhaki I., Gerchman Y., Halpern M. Bacterial communities in floral nectar. Environ. Microbiol. Reports. 2012;4:97–104. doi: 10.1111/j.1758-2229.2011.00309.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Genersch E. Honey bee pathology: current threats to honey bees and beekeeping. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2010;87:87–97. doi: 10.1007/s00253-010-2573-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Granok A.B., Benjamin P., Garrett L.S. Corynebacterium minutissimum bacteremia in an immunocompetent host with cellulitis. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2002;35:e40–e42. doi: 10.1086/341981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeyaprakash A., Hoy M.A., Allsopp M.H. Bacterial diversity in worker adults of Apis mellifera capensis and Apis mellifera scutellata (Insecta: Hymenoptera) assessed using 16S rRNA sequences. J. Invert. Pathol. 2003;84:96–103. doi: 10.1016/j.jip.2003.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang S., Zheng B., Ding W., Lv L., Ji J., Zhang H., Xiao Y., Li L. Whole-genome sequence of Staphylococcus hominis, an opportunistic pathogen. J. Bacteriol. 2012;194:4761–4762. doi: 10.1128/JB.00991-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kacaniova M., Chlebo R., Kopernický M., Trakovicka A. Microflora of the honeybee gastrointestinal tract. Folia Microbiol. 2004;49(2):169–171. doi: 10.1007/BF02931394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khan I.A., Khan A., Asif H., Jiskani M.M., Mühlbach H.-P., Azim M.K. Isolation and 16s rDNA sequence analysis of bacteria from dieback affected mango orchards in southern Pakistan. Pak. J. Bot. 2014;46:1431–1435. [Google Scholar]

- Khan K.A., Ansari M.J., Al-Ghamdi A., Nuru A., Harakeh S. Investigation of gut microbial communities associated with indigenous honey bee (Apis mellifera jemenitica) from two different eco-regions of Saudi Arabia. Saudi J. Biol. Sci. 2017;24:1061–1068. doi: 10.1016/j.sjbs.2017.01.055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein A.-M., Vaissiere B.E., Cane J.H., Steffan-Dewenter I., Cunningham S.A., Kremen C., Tscharntke T. Importance of pollinators in changing landscapes for world crops. Proc. Roy. Soc. B: Biol. Sci. 2007;274:303–313. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2006.3721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J., Qin H., Wu J., Sadd B.M., Wang X., Evans J.D., Peng W., Chen Y. The prevalence of parasites and pathogens in Asian honeybees Apis cerana in China. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e47955. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0047955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinson V.G., Danforth B.N., Minckley R.L., Rueppell O., Tingek S., Moran N.A. A simple and distinctive microbiota associated with honey bees and bumble bees. Mol. Ecol. 2011;20:619–628. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2010.04959.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinson V.G., Moy J., Moran N.A. Establishment of characteristic gut bacteria during development of the honeybee worker. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2012;78(8):2830–2840. doi: 10.1128/AEM.07810-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marwat S.K., Khan M.A., Rehman F., Khan K. Medicinal uses of honey (Quranic medicine) and its bee flora from Dera Ismail Khan District, KPK, Pakistan. Pak. J. Pharm. Sci. 2013;26:307–314. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mattila H.R., Seeley T.D. Genetic diversity in honey bee colonies enhances productivity and fitness. Science. 2007;317:362–364. doi: 10.1126/science.1143046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muli E., Patch H., Frazier M., Frazier J., Torto B., Baumgarten T., Kilonzo J., Kimani J.N., Mumoki F., Masiga D., Tumlinson J., Grozinger C. Evaluation of the distribution and impacts of parasites, pathogens, and pesticides on honey bee (Apis mellifera) populations in East Africa. PLoS ONE. 2014;9:e94459. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0094459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olofsson T.C., Vásquez A. Detection and identification of a novel lactic acid bacterial flora within the honey stomach of the honeybee Apis mellifera. Curr. Microbiol. 2008;57:356–363. doi: 10.1007/s00284-008-9202-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pesquero, M.A., Carneiro, L.C., Pires, D.D.J., 2012. Insect/bacteria association and nosocomial infection, In: Kumar, Y. (Ed.), Salmonella, A Diversified Superbug, pp 449–468, <www.intechopen.com>.

- Potts S.G., Biesmeijer J.C., Kremen C., Neumann P., Schweiger O., Kunin W.E. Global pollinator declines: trends, impacts and drivers. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2010;25:345–353. doi: 10.1016/j.tree.2010.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prabhakar C.S., Sood P., Kanwar S.S., Sharma P.N., Kumar A., Mehta P.K. Isolation and characterization of gut bacteria of fruit fly, Bactrocera tau (Walker) Phytoparasitica. 2013;41:193–201. [Google Scholar]

- Ryan M., Adley C. Sphingomonas paucimobilis: a persistent Gram-negative nosocomial infectious organism. J. Hosp. Infect. 2010;75:153–157. doi: 10.1016/j.jhin.2010.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soto-Arias J.P., Groves R.L., Barak J.D. Transmission and retention of Salmonella enterica by phytophagous hemipteran insects. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2014;80:5447–5456. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01444-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- vanEngelsdorp D., Meixner M.D. A historical review of managed honey bee populations in Europe and the United States and the factors that may affect them. J. Invert. Pathol. 2010;103:S80–S95. doi: 10.1016/j.jip.2009.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vignaroli C., Biavasco F., Varaldo P.E. Interactions between glycopeptides and β-lactams against isogenic pairs of teicoplanin-susceptible and -resistant strains of Staphylococcus haemolyticus. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2006;50:2577–2582. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00260-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waghchoure-Camphor E.S., Martin S.J. Beekeeping in Pakistan: a bright future in a troubled land. Am. Bee J. 2008;148:726–728. [Google Scholar]

- Yoshiyama M., Kimura K. Bacteria in the gut of Japanese honeybee, Apis cerana japonica, and their antagonistic effect against Paenibacillus larvae, the causal agent of American foulbrood. J. Invertebr. Pathol. 2009;102(2):91–96. doi: 10.1016/j.jip.2009.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou G., Luo X., Tang Y., Zhang L., Yang Q., Qiu Y., Fang C. Kocuria flava sp. nov. and Kocuria turfanensis sp. nov., airborne actinobacteria isolated from Xinjiang, China. Inter. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2008;58:1304–1307. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.65323-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]