Highlights

-

•

Graded activity and physiotherapy have similar effects in terms of reducing pain and disability.

-

•

Healthcare professionals may identify inadequate beliefs in patients with low back pain.

-

•

It is important to stimulate patients with LBP return to work.

Keywords: Low back pain, Physical therapy, Rehabilitation, Exercise

Abstract

Background

Low back pain (LBP) is a major health and economic problem worldwide. Graded activity and physiotherapy are commonly used interventions for nonspecific low back pain. However, there is currently little evidence to support the use of one intervention over the other in the medium-term.

Objective

To compare the effectiveness of graded activity exercises to physiotherapy-based exercises at mid-term (three and six months’ post intervention) in patients with chronic nonspecific LBP.

Methods

Sixty-six patients were randomly allocated to two groups: graded activity group (n = 33) and physiotherapy group (n = 33). These patients received individual sessions twice a week for six weeks. Follow-up measurements were taken at three and six months. The main outcome measurements were intensity pain (Pain Numerical Rating Scale) and disability (Rolland Morris Disability Questionnaire).

Results

No significant differences between groups after three and six month-follow ups were observed. Both groups showed similar outcomes for pain intensity at three months [between group differences: −0.1 (95% confidence interval [CI] = −1.5 to 1.2)] and six months [0.1 (95% CI = −1.1 to 1.5)], disability at three months was [-0.6 (95% CI = −3.4 to 2.2)] and six months [0.0 (95% CI = −2.9 to 3.0)].

Conclusion

The results of this study suggest that graded activity and physiotherapy have similar effects in the medium-term for patients with chronic nonspecific low back pain.

Introduction

Low back pain is the highest contributor to disability in the world and the average lifetime prevalence of LBP is 39% in adults with LBP in the world.1 However, less than 60% of people with low back pain actually seek treatment.2 In Brazil, LBP is the second most frequent health complaint while it is estimated that 11.9% of the population suffers from chronic back problems at any given time.1 The duration of symptoms is highly associated with the prognosis of LBP3 with patients with acute LBP having a better prognosis compared with those with chronic symptoms.

According to the guidelines on management of LBP,4 there is a wide variety of approaches recommended for chronic LPB such as supervised exercises and cognitive behavioral therapy. Supervised exercises incorporated in physical therapy treatment (strengthening, stretching and motor control exercises) and graded activity exercises under the principles of cognitive-behavioral therapy have been shown to be no more effective than other forms of exercise in reducing intensity of pain and disability in patients with chronic LBP. However, these reviews included patients with acute and subacute pain, whereas the current review focused on chronic, nonspecific conditions.5 Moreover, stretching, strengthening and motor control exercise are among the most commonly used interventions provided by physical therapists in the management of patients with chronic LBP.6

Graded activity exercises use a cognitive-behavioral approach to increase activity tolerance by addressing pain-related fear, kinesiophobia, and unhelpful beliefs and behaviors concerning back pain while addressing physical impairments such as impaired endurance, muscle strength, and balance.7, 8 Then, Graded activity consists of three phases: measuring functional capacity, educating in the workplace and providing an individual program of submaximal exercise that is gradually increased.7 Then, once a week physiotherapist and patient's interaction to discussing important point about booklet to help patients to minimize risk about unhelpful beliefs and behaviors about pain. Additionally, a graded activity program focuses on identifying specific activities the patients have difficulty performing due to LBP and goals were formulated to serve as references.9 The treatment principle was guided by the patient's feedback with respect to functional abilities. The key features of the program are the use of pacing, exercise quotas, and patients ‘self-reinforcement of healthy behavior. Quotas were set for frequencies, loads, repetitions, and duration for each activity was establish to each patient.9

The efficacy of graded activity exercises for LPB is conflicting with a recent systematic review showing that while this approach is effective for pain, disability and return to work compared to control interventions (e.g. waiting lists), they tend to be equally effective compared to other forms of exercise such as motor control exercises in the short term.5 Potential limitations in previous trials that used graded activity in patients with chronic LBP are the low methodological quality, the use of low dosage of treatment (e.g. one treatment session per week)10 and the use of heterogeneous patient populations with acute, sub-acute, and chronic low back pain.5, 11

There is a paucity of studies that compared graded activity exercises to physical therapy exercises in patients with chronic nonspecific LBP. We have previously showed that graded activity exercises offer similar effects in terms of pain intensity and disability when compared with physiotherapy exercises (strengthening, stretching and motor control exercises).6 However, our previous publication only reported results for short-term, i.e. immediate post intervention. Therefore, the aim of this study was to compare the effectiveness of graded activity exercises to physiotherapy-based exercises at mid-term (three and six-month post intervention) in patients with chronic nonspecific LBP.

Methods

This was a two-arm, single-blinded, randomized controlled trial. The study was approved a priori by the local ethics committee at the Universidade de Sao Paulo (USP), São Paulo, SP, Brazil (Protocol 393/12), prospectively registered at clinicaltrial.gov (registration number: NCT01719276) with a published protocol outlining trial procedures.12 The study was conducted in a Rehabilitation setting affiliated with a public hospital in the city of Sao Paulo, Brazil. Patients seeking treatment for LBP from both genders were recruited.

A physiotherapist who was blinded to treatment allocation, screened patients in order to confirm eligibility criteria, collect demographic and anthropometric data and assess outcomes. Patients were included in the trial if they were suffering with chronic nonspecific LBP (triaged and diagnosed by an orthopedic specialist), aged between 18 and 65 years, and presenting with a minimum pain intensity score of three in the 11-point Pain Numerical Rating Scale.13 Participants were excluded if they had any of the following criteria: known or suspected serious spinal pathology (e.g., fractures, tumors, inflammatory, rheumatologic disorders, or infective diseases of the spine), nerve root compromise (diagnosed by a radiologist through magnetic resonance imaging), scheduled or a history of previous spinal surgery, and comorbid health conditions that could prevent active participation in the exercise programs such as high blood pressure, pregnancy, or cardio-respiratory illnesses. In order to ensure patients’ safe participation in the study, the Physical Activity Readiness Questionnaire (PAR-Q)14 was used. Those answering “yes” to any of the questionnaire's questions were excluded from the study. All participants were invited to sign the participant consent form.

Randomization and allocation

A randomization code was created using Microsoft Excel for Windows software (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, Washington) by a researcher who was not involved in the recruitment process. The allocation schedule was concealed by using consecutively numbered, sealed, opaque envelopes. After baseline assessment, eligible participants were referred to a physiotherapist overseeing the trial interventions, who conducted their randomized allocation to one of the treatment groups. The assessor was blinded to treatment allocation. Given the nature of the interventions, it was not possible to blind physiotherapists or patients.

Intervention

The intervention period lasted for six weeks, with one-hour exercise sessions implemented twice per week. Both exercise interventions were led by experienced clinician (mean years of practice = 7 years) who received 10 h of training on the concepts, practical aspects, and progression of exercises. Participants were instructed not to participate in any other intervention during the treatment period. There was no interference in the use of medication.

Physiotherapy exercise group

The physiotherapy exercise group was based on the protocol reported by Franca et al.15 The program comprised of stretching exercises of main muscle groups (e.g. erector spinae, hamstrings, and triceps surae), strengthening exercises (e.g. abdominal curl-ups, trunk extension), and motor control exercises (e.g. low load exercises of deep trunk muscles such as tranversus abdominus and multifidus). The physiotherapy exercise group did not receive hands-on interventions such as manual therapy techniques. All sessions had the same protocol exercise, with no progression of exercise levels implemented. The patients were not instructed to exercises at home. Details of the exercises program is presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Description of the exercises for the physiotherapy group.

| Exercise | Position | Sets/duration |

|---|---|---|

| Stretching | Stretching of the ES in dorsal decubitus, with flexed hips and knees; Stretching of the HS and TS in dorsal decubitus, with forced flexion of 1 limb at a time with assistance of the physical therapist; Stretching of the ES with the patient sitting on heels, flexed trunk with the abdomen resting on the front of the thighs; Global stretching of the posterior muscular chain (TS, HS, ES) 2 series of 4 min were performed, with 1minute of resting interval. |

3 sets of 30 s Intervals between series of 30 s |

| Strengthening | Exercises for the rectus abdominis in dorsal decubitus with flexed knees: trunk flexion; Exercises for the rectus abdominis, external and internal obliquus in dorsal decubitus and flexed knees: trunk flexion and rotation; Exercises for the rectus abdominis in dorsal decubitus and semi-flexed knees: hip flexion; Exercises for the erector spinae in ventral decubitus: trunk extension. |

2 sets of 12 repetitions Intervals between series of 30 s |

| Motor control | Exercises for the lumbar multifidus in ventral decubitus; Exercises for the transversus abdominis muscle in dorsal decubitus with flexed knees; Exercises for the transversus abdominis muscle in 4 point kneeling; Co-contraction of the transversus abdominis muscle and lumbar multifidus in the upright position. |

2 sets of 10 repetitions Intervals between series of 30 s |

Graded activity group

The graded activity group followed the program described by Macedo et al.16 and Smeets et al.17 and was based on individual sessions of progressive and sub-maximal exercises aimed at improving physical fitness and stimulate changes in behavior and patients’ attitudes toward pain. The program consisted of aerobic training on a treadmill and lower limb strengthening exercises. To determine the load of strengthening exercises, the 10-repetition maximum test was used.18 During the first two weeks of training, individuals exercised using 50% of their maximum load. On the third and fourth week, loads were increased to 60% maximum, and during the final two weeks, they were further increased to 70% maximum. Heart rate (HR) was calculated using the formula of Karvonen (HRmax = 200–age), with the formula adjusted for sedentary individuals: Exercise HR = Resting HR + 70% to 80% of maximum HR.19 Participants also received an educational booklet (based on the “Back Book”20) with important information on how to care for the spine. Details of the exercises programmer is presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Description of the exercises for the graded activity group.

| Exercise | Position | Sets/duration |

|---|---|---|

| Aerobic training on the treadmill | 5-minute warm-up with speed of 5–8 km/h; 20-minute submaximal training at 70–80% maximum heart rate; 5-minute slow-down with gradual speed reduction. |

|

| Lower limbs strengthening | Exercise for the quadriceps in sitting position; Exercise for the hamstrings in standing position |

3 sets of 12 repetitions for each limb Intervals between series of 30 s |

| Trunk strengthening | Exercises for the erector spinae in ventral decubitus: trunk extension. | 3 sets of 10 repetitions Intervals between series of 30 s |

Assessment of clinical outcomes

The assessments were conducted at baseline, six weeks (after treatment discharge), three and six months follow ups with the results from the short-term (six weeks) follow up being previously published.6 All measurements were conducted by a trained physical therapist blinded to group allocation. The validated Brazilian-Portuguese versions of the scales and questionnaires were used.21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26

Primary outcomes

There were two primary outcomes for this study: pain intensity and disability. Pain intensity was assessed by the Pain Numerical Rating Scale (NRS), an 11-point scale ranging from 0 to 10, where 0 represents the absence of pain, and 10 represents unbearable pain.13 Participants were asked to focus on their average pain levels over the week before assessment.13 Disability was assessed by the Roland Morris Disability Questionnaire, a 24-item questionnaire that assesses normal activities of daily living. Participants were asked to tick the items that they perceived as difficult to perform due to LBP. Each answer is scaled either “no” (difficulty = 0 points) or “yes” (difficulty = 1 point), thus leaving a range of scores from 0 to 24, with a higher score indicating a higher level of disability.13

Secondary outcomes

Secondary outcomes were quality of pain, quality of life, global perceived effect, return to work, kinesiophobia, daily physical activity and physical capacity. Quality of pain was assessed by the McGill Pain Questionnaire21, 27 which allows for a multidimensional assessment of pain. It consists of 78 descriptors assigned with intensity values that are grouped into four major domains (sensory, affective, evaluative, and miscellaneous) and 20 subdomains, each with two to six descriptors. The questionnaire is used to describe pain experience and provides a total score that corresponds to the sum of the values from each chosen descriptor. Maximal scores are as follows: sensorial = 41, affective = 14, evaluative = 5, miscellaneous = 17, total = 77.27

Quality of life was assessed by Short-Form Health Survey Questionnaire (SF-36), which consists of 36 questions grouped into eight domains: vitality (four items), physical functioning (ten items), bodily pain (two items), general health perception (five items), physical role functioning (two items), emotional role functioning (three items), social role functioning (two items), and mental health (five items). For each section, scores range from 0 to 100, with higher scores reflecting a better quality of life. The study focused on physical and emotional role functioning. Global perceived effect was assessed by the global perceived effect scale. This 11-point numerical scale compares symptoms upon treatment's end with those at pre-treatment. The scale ranges from −5 to +5, with negative values reflecting a worsening of symptoms (−5 being the most significant in this sense), and positive values reflecting improvement (+5 reflecting total recovery).13

Return to work was assessed at post-treatment assessments, participants were asked if they were working. If the participants answered “no” to this question, they were further questioned if they were not working due to low back pain. Kinesiophobia was assessed by The Tampa Scale of Kinesiophobia (TSK) a self-applied questionnaire consisting of 17 items that was developed to measure fear of movement due to chronic low back pain. Each question has four response options: totally disagree (1 point), partially disagree (2 points), partially agree (3 points), and totally agree (4 points). The scores of questions 4, 8, 12, and 16 were obtained through an inversion of the response values. The total score of the questionnaire corresponds to the sum of the scores of all questions and ranges from 17 to 68 points.28

Daily physical activity was assessed by Baecke Questionnaire of Habitual Physical Activity which measures physical activity in three domains: occupational activity, physical exercises, and leisure and locomotion. It consists of 16 questions structured using a quantitative Likert scale. The score is calculated by the sum of the domain scores. Physical activity is stratified as mild (3.0–6.7), moderate (6.8–8.1) and intense (8.2–15.0).29 Physical capacity was assessed by sit-to-stand and 15.2 m walking test was performed. Five repetitions of the sit-to-stand test were used at maximal speed without use of the hands. After five minutes, the walking test was performed. Patients walked 7.62 m around two obstacles and returning to their initial position. Patients repeated the walking test after an interval of three minutes, and the average value was used for analysis. Time was measured using a digital manual stopwatch (instrutherm®).

Sample size

Based on an a priori power calculation, the sample size was adequate to detect a two-point minimum difference between groups in terms of pain intensity measured on the Pain Numerical Rating Scale, assuming a standard deviation of 1.9 points. The study also sought to detect a 4-point difference in functional disability measured on the Roland Morris Disability Questionnaire, with an estimated standard deviation of 4.9 points. Power was set as 80% for an alpha of 5% and attrition (drop-outs) of 15%. The required sample was set at 33 patients per group.

Statistical analysis

Data normality was tested through visual inspection of histograms. Multivariate repeated measures analysis of variance (MANOVA) was used to investigate the effect of treatment group (graded activity vs. physiotherapy), time (baseline, 3, and 6 months follow up), and interaction between treatment groups and time. Univariate ANOVAs were used to identify the variables that were different for each significant main or interaction effect. Pairwise comparisons were used to compare baseline to each follow up. The SPSS version 21 software (SPSS Inc, Chicago, Illinois) was used for the analyses, which were performed on an intention-to-treat basis. The confidence interval was a priori established at 95%.

Results

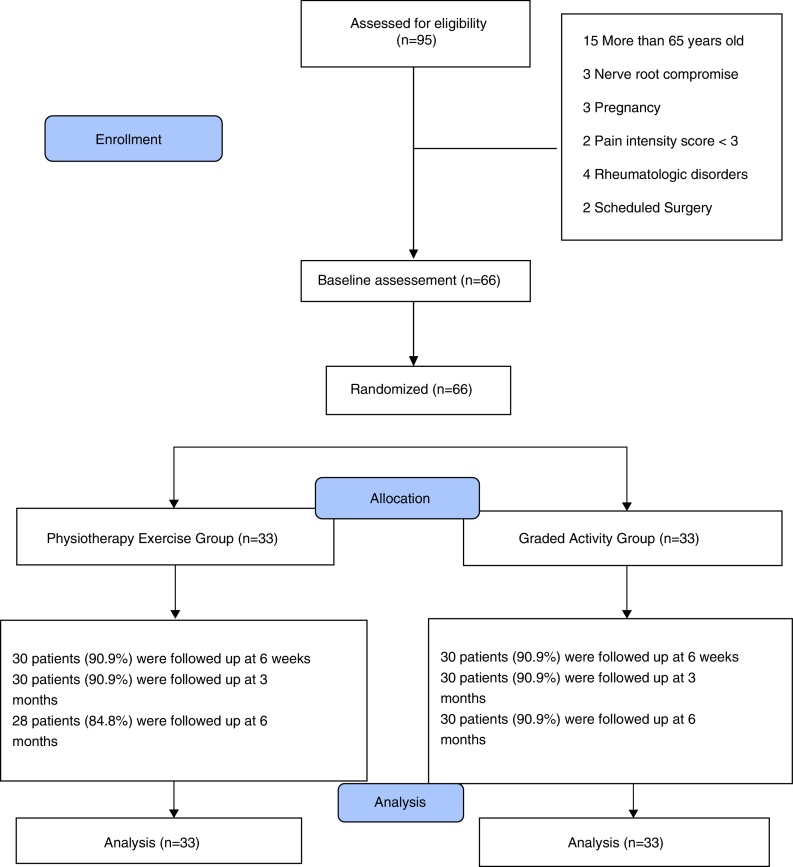

Ninety-five potential participants were contacted; of these 29 were excluded: 15 were older than 65 years old, three were diagnosed with nerve root compromise, three were pregnant, two presented with symptoms of pain less than 3/10, four were diagnosed with rheumatologic disorders and two had scheduled surgery (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of participants through the study.

Sixty-six individual were selected, and average score for higher pain intensity was 7 points (physiotherapy exercise group: mean = points, SD = 2.1; Graded activity group: mean = 7.6 points, SD = 1.7). The baseline characteristics of both groups, including effect modifiers investigated in this study, were similar. Nearly 73% of the patients were women, and the average symptom duration was approximately 6 years. Patients generally had moderate levels of pain and disability (Table 3). A total of 396 treatment sessions were provided in the trial. Patients in the physiotherapy exercise attended 91.4% of the sessions, while those in the graded activity group attended 91.9%.

Table 3.

Baseline characteristics of subjects by group.

| Physiotherapy exercise group (n = 33) | Graded activity group (n = 33) | |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 46.6 (9.5) | 47.2 (10.5) |

| Weight (kg) | 69.4 (12.2) | 71.8 (10.7) |

| Height (cm) | 1.61 (0.09) | 1.60 (0.08) |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 26.7 (4.6) | 27.8 (4.3) |

| Gender (male/female) | 8 (24.2%); 25 (75.7%) | 9 (27.2%); 24 (72.7%) |

| Marital status | ||

| Single | 4 (12.1) | 10 (30.3) |

| Married | 25 (73.7) | 21 (63.6) |

| Divorced | 2 (6.6) | 1 (3.3) |

| Widowed | 2 (6.0) | 1 (3.3) |

| Duration of symptoms (months) | 54.4 (40.6) | 79.6 (101.3) |

| Academic level | ||

| Primary education | 20 (60.6) | 22 (66.6) |

| Secondary education | 12 (36.3) | 10 (30.3) |

| Tertiary education | 1 (3.0) | 1 (3.0) |

| Use of medication | 18 (54.4) | 14 (42.4) |

| Physiotherapy treatment | 21 (63.6) | 19 (57.5) |

| Pain intensity (0–10) | 7.2 (2.1) | 7.6 (1.7) |

| Disability (0–24) | 13.7 (5.1) | 12.9 (4.9) |

The categorical variables are expressed as n (%) and the continuous variable are expressed as mean (standard deviations).

As expected in this hypothesis-setting study, none of the interaction terms for any findings for these outcomes were statistically significant. Univariate ANOVAs revealed that time had a significant effect on all outcome variables IC. Both treatments had similar effects in reducing pain intensity and disability. Similar improvements for all the secondary outcomes (p < 0.001) were observed.

Both groups showed similar outcomes for pain intensity at three months [between group differences: was −0.1 points (95% CI = −1.5 to 1.2) and six months was 0.1 points (95% CI = −1.1 to 1.5), disability at three months was [−0.6 (95% CI = −3.4 to 2.2)] and six months [0.0 (95% CI = −2.9 to 3.0)] in Table 4.

Table 4.

Means (standard deviation) and difference between group at baseline, posttreatment, 3 and 6 months’ follow-ups.

| Outcomes | Unadjusted mean (mean, SD) |

Between groups difference in change score | p* | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Physiotherapy group | Graded activity group | |||

| Intensity pain (0–10)# | ||||

| Baseline | 7.6 (2.0) | 7.2 (1.9) | ||

| Posttreatment | 2.5 (1.9) | 2.4 (1.4) | 0.1 (−0.7 to 1.0) | .71 |

| 3 mo | 4.1 (3.1) | 4.2 (2.1) | −0.1 (−1.5 to 1.2) | .84 |

| 6 mo | 4.1 (3.1) | 4.0 (1.9) | 0.1 (−1.1 to 1.5) | .80 |

| Disability (0–24)# | ||||

| Baseline | 12.8 (4.8) | 12.9 (4.9) | ||

| Posttreatment | 6.3 (5.5) | 6.5 (4.2) | −0.2 (−2.7 to 2.3) | .87 |

| 3 mo | 7.2 (6.0) | 7.8 (5.0) | −0.6 (−3.4 to 2.2) | .67 |

| 6 mo | 7.4 (6.2) | 7.4 (5.2) | −0.0 (−2.9 to 3.0) | .98 |

| McGill total (0–77)# | ||||

| Baseline | 39.6 (12.2) | 39.4 (12.0) | ||

| Posttreatment | 19.2 (16.0) | 22.7 (15.6) | −3.4 (−11.5 to 4.6) | .40 |

| 3 mo | 13.4 (13.8) | 16.5 (12.1) | −3.1 (−9.9 to 3.5) | .35 |

| 6 mo | 12.6 (12.2) | 13.2 (8.4) | −0.5 (−5.9 to 4.8) | .83 |

| Sensory (0–41)# | ||||

| Baseline | 21.8 (7.1) | 22.5 (6.6) | ||

| Posttreatment | 11.2 (9.2) | 13.4 (8.8) | −2.1 (−6.8 to 2.5) | .36 |

| 3 mo | 10.2 (8.4) | 11.2 (8.6) | −1.0 (−5.4 to 3.4) | .65 |

| 6 mo | 8.1 (7.7) | 8.4 (5.7) | −0.3 (−3.8 to 3.2) | .86 |

| Affective (0–14)# | ||||

| Baseline | 6.0 (2.8) | 6.1 (3.7) | ||

| Posttreatment | 3.3 (3.5) | 3.0 (3.3) | 0.3 (−1.4 to 2.0) | .73 |

| 3 mo | 1.4 (2.3) | 2.0 (2.6) | −0.6 (−1.8 to 0.6) | .35 |

| 6 mo | 0.8 (1.7) | 1.6 (2.0) | −0.7 (−1.7 to 0.2) | .13 |

| SF-36 – physical role functioning (0–100)# | ||||

| Baseline | 27.2 (36.6) | 25.0 (32.4) | ||

| Posttreatment | 68.3 (36.5) | 75.0 (30.7) | −6.6 (−24.1 to 10.7) | .44 |

| 3 mo | 69.1 (40.8) | 64.1 (30.5) | 5.0 (−13.6 to 22.6) | .59 |

| 6 mo | 56.2 (43.3) | 69.1 (26.8) | −12.9 (−31.7 to 5.9) | .17 |

| SF-36 – emotional role functioning (0–100)# | ||||

| Baseline | 49.5 (43.4) | 43.8 (42.0) | ||

| Posttreatment | 78.8 (36.6) | 84.3 (27.4) | −5.4 (−22.1 to 11.2) | .51 |

| 3 mo | 88.8 (33.1) | 87.4 (26.2) | 1.4 (−14.0 to 16.8) | .85 |

| 6 mo | 89.8 (36.6) | 88.8 (25.3) | 1.0 (−13.5 to 16.2) | .78 |

| Global perceived effect (−5 to +5)# | ||||

| Baseline | −2.6 (2.6) | −2.8 (2.0) | ||

| Posttreatment | 3.7 (1.0) | 3.3 (1.2) | 0.3 (−0.2 to 0.9) | .22 |

| 3 mo | 2.6 (2.3) | 2.2 (2.0) | 0.3 (−0.8 to 1.4) | .56 |

| 6 mo | 2.5 (2.3) | 2.2 (2.4) | 0.3 (−0.8 to 1.5) | .55 |

| Kinesiophobia (17–68)# | ||||

| Baseline | 45.0 (7.3) | 42.9 (7.8) | ||

| Posttreatment | 35.5 (9.0) | 36.7 (7.9) | −1.2 (−5.6 to 3.2) | .58 |

| 3 mo | 38.7 (8.0) | 37.7 (7.4) | 1.0 (−2.9 to 4.9) | .61 |

| 6 mo | 39.7 (7.7) | 38.7 (6.0) | 1.0 (−2.5 to 4.6) | .56 |

| Daily physical activity (3–15)# | ||||

| Baseline | 6.7 (0.6) | 7.1 (0.7) | ||

| Posttreatment | 7.2 (0.9) | 7.8 (0.9) | −0.5 (−0.9 to 0.1)** | .01 |

| 3 mo | 6.3 (2.1) | 6.9 (0.8) | −0.6 (−1.4 to 0.1) | .16 |

| 6 mo | 7.0 (0.9) | 7.1 (0.9) | −0.1 (−0.5 to 0.3) | .67 |

| Physical fitness | ||||

| Sit-to-stand test | ||||

| Baseline | 25.0 (7.3) | 22.8 (8.6) | ||

| Posttreatment | 17.7 (4.7) | 18.6 (8.1) | −0.8 (−4.2 to 2.6) | .63 |

| 3 mo | 18.4 (4.3) | 17.3 (5.7) | 1.0 (−1.5 to 3.7) | .41 |

| 6 mo | 17.5 (4.1) | 15.9 (5.0) | 1.6 (−0.7 to 4.0) | .17 |

| 15.2 walking test | ||||

| Baseline | 16.3 (3.9) | 15.5 (3.7) | ||

| Posttreatment | 13.8 (1.5) | 13.5 (2.6) | 0.2 (−0.8 to 1.4) | .60 |

| 3 mo | 14.7 (1.7) | 14.3 (2.9) | 0.3 (−0.9 to 1.6) | .57 |

| 6 mo | 14.6 (3.0) | 14.3 (2.7) | 0.3 (−1.1 to 1.8) | .67 |

Normal range; SD, standard deviation; CI, 95% confidence interval.

p value of between group comparison analyses by Repeat Measure ANOVA. Significant differences are marked in bold (p < 0.05).

Significantly different (p < 0.05).

We observed improvements in daily physical activity (mean difference = −0.5 points; 95% CI = −0.9 to 0.1 points) in favor of the Graded activity group after the intervention. However, we did not observe between-group differences at the 3 and 6-month follow-up for any of the outcomes (Table 4). For return to work, the Pearson chi-square also revealed no significant difference between groups at 3 months (p = >.64) and 6 months (p = >.98).

Some of the activities reported by the Graded Activity group as difficult to perform due to LBP include remaining seated for too long (15%), staying out of bed (18%), picking up objects from the floor (15%), daily home activities (30%), weight lifting (15%), and others (21%). Based on these percentages, the patients received postural guidelines to avoid overloading the spine and better perform these activities.

Discussion

The aim of this randomized controlled trial was to compare the effectiveness of graded activity exercises to physiotherapy-based exercises at mid-term (3 and 6-month post intervention) in patients with chronic nonspecific LBP. Both treatments had similar effects for the primary outcomes in reducing pain intensity and disability in the short-term and mid-term.6 Furthermore, we observed that in the medium term follow up (3 and 6 months), patients largely maintained the beneficial effects of the interventions for all outcomes. These results can be considered clinically significant for both groups, given that the difference in the means before and 6 months is greater than 2 points for intensity pain and greater than 5 points for disability.30

No significant difference between groups was found for pain intensity and disability at 3 and 6 months. A possible interpretation for this result is that as both interventions are active exercises they may have similar effects for patients with chronic LBP.4 There is substantial evidence demonstrating the beneficial effects of physical activity on physical health. Furthermore, four studies that compare graded activity with other form of exercise (motor control,9 guidelines31 and usual physiotherapy32) are in line with our study and also observed no difference between groups for pain intensity and disability in the medium term follow up in patients with chronic nonspecific LPB. Therefore, it is probably unlikely that significant differences for pain are observed in LBP trials when the study is designed with both treatment groups performing active exercises. Furthermore, these results are consistent with the recent treatment guidelines for patients with chronic LBP4 and a systematic review that suggested that different forms of exercise have similar effects for patients with chronic LBP.33 A comparison between graded activity and other forms of exercises, a recent systematic rewiew34 found that graded activity is not more effective than other forms of exercise for persistent LBP in short, medium and long term.

Although either graded activity or physiotherapy are effective for patients with chronic LBP, it is important to note that a clinical prediction rule may be able to identify possible subgroups of patients who respond better than others to graded activity or physiotherapy. Although Macedo et al.,35 observed a statistically significant and clinically important modifier of treatment response for the outcome of function at 12 months (interaction: 2.72; 95% CI: 1.39 to 4.06) with patients who scored low on the questionnaire of clinical instability (LSIQ score 9) showing better outcomes of function treated with graded activity when compared with motor control exercise. This is important to clarify that the LSIQ is not yet a clinical prediction rule, it may be an interval-level measure or an index. There is still no evidence showing whether it measures instability or another construct in LBP. So, although the LSIQ is promising and can be of some importance if can predict graded activity or motor control exercise, we cannot oversell its importance at this stage until further evidence shows otherwise.36

For the physiotherapy group, it is difficult to develop a clinical prediction rule because this treatment approach is based in three different kinds of exercise (stretching, strengthening and motor control exercises). However, currently is hard to predict a clinical prediction rules (CPRs) for LBP. According to a recent systematic review,37 there are 13 diagnostic CPRs for LBP have been developed from clustering of diagnostic clinical tests. Among those, 1 tool for identifying lumbar spinal stenosis and 2 tools for identifying inflammatory back pain having undergone validation and no studies have yet undergone impact analysis. Then, diagnostic CPRs for LBP are in their initial development phase and cannot be recommended for use in clinical practice.

The results of this randomized controlled trial suggest that physiotherapists may have the choice for graded activity or physiotherapy approaches in the treatment for patients with chronic nonspecific LBP. Moreover, patients’ preferences could be important in treatment selection. The results of this clinical trial are for three and six-month follow-up; future studies should investigate longer-term follow-ups.

One of the strengths of this study was that we recruited patients seeking treatment for chronic low back pain that can be representative of the population. Moreover, this randomized controlled trial had a low risk of bias by including a sample size calculation, concealed allocation, adequate randomization procedures, blinding assessor, similarity at baseline and intention to treat analysis and the protocol of the exercises were designed and published previously.12 The treatments were conducted by a single therapist who was trained to perform the interventions and there was excellent treatment adherence. The main limitation of this study was that the therapist and patients were not blinded to group allocation. However, it is not possible to blind therapists and patients in a randomized controlled trial with exercises. Thus, there are no studies in the literature that include blinded therapists or patients using exercise as a form of treatment. Other possible limitation of this study is we did not include a control or placebo group and the sample size. We did not use a control group because a recent Cochrane systematic review that investigated the effect of exercise therapy in patients with chronic LBP concluded that exercise therapy (regardless of the type of exercise) is at least 10 points (on a scale of 0–100 points) more effective than no treatment.33

In conclusion, the results of this trial suggest that graded activity and physiotherapy exercise have similar effects in terms of reducing pain, disability, quality of life, global perceived effect, return to work, physical activity, physical capacity and kinesiophobia.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

The trials register number NCT01719276 clinicaltrials.gov.

References

- 1.Nascimento P.R., Costa L.O. Low back pain prevalence in Brazil: a systematic review. Cad Saude Publica. 2015;31(6):1141–1156. doi: 10.1590/0102-311X00046114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ferreira M.L., Machado G., Latimer J., Maher C., Ferreira P.H., Smeets R.J. Factors defining care-seeking in low back pain—a meta-analysis of population based surveys. Eur J Pain. 2010;14(7):747. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpain.2009.11.005. e1–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Costa Lda C., Maher C.G., McAuley J.H. Prognosis for patients with chronic low back pain: inception cohort study. BMJ. 2009;339:b3829. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b3829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Delitto A., George S.Z., Van Dillen L.R. Low back pain. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2012;42(4):A1–A57. doi: 10.2519/jospt.2012.42.4.A1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Macedo L.G., Smeets R.J., Maher C.G., Latimer J., McAuley J.H. Graded activity and graded exposure for persistent nonspecific low back pain: a systematic review. Phys Ther. 2010;90(6):860–879. doi: 10.2522/ptj.20090303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Magalhaes M.O., Muzi L.H., Comachio J. The short-term effects of graded activity versus physiotherapy in patients with chronic low back pain: a randomized controlled trial. Man Ther. 2015;20(4):603–609. doi: 10.1016/j.math.2015.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lopez-de-Uralde-Villanueva I., Munoz-Garcia D., Gil-Martinez A. A systematic review and meta-analysis on the effectiveness of graded activity and graded exposure for chronic nonspecific low back pain. Pain Med. 2016;17(1):172–188. doi: 10.1111/pme.12882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pengel L.H., Refshauge K.M., Maher C.G., Nicholas M.K., Herbert R.D., McNair P. Physiotherapist-directed exercise, advice, or both for subacute low back pain: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2007;146(11):787–796. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-146-11-200706050-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Macedo L.G., Latimer J., Maher C.G. Effect of motor control exercises versus graded activity in patients with chronic nonspecific low back pain: a randomized controlled trial. Phys Ther. 2012;92(3):363–377. doi: 10.2522/ptj.20110290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nicholas M.K., Wilson P.H., Goyen J. Comparison of cognitive-behavioral group treatment and an alternative non-psychological treatment for chronic low back pain. Pain. 1992;48(3):339–347. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(92)90082-M. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.van der Giessen R.N., Speksnijder C.M., Helders P.J. The effectiveness of graded activity in patients with non-specific low-back pain: a systematic review. Disabil Rehabil. 2012;34(13):1070–1076. doi: 10.3109/09638288.2011.631682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Magalhaes M.O., Franca F.J., Burke T.N. Efficacy of graded activity versus supervised exercises in patients with chronic non-specific low back pain: protocol of a randomised controlled trial. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2013;14:36. doi: 10.1186/1471-2474-14-36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Costa L.O., Maher C.G., Latimer J. Clinimetric testing of three self-report outcome measures for low back pain patients in Brazil: which one is the best? Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2008;33(22):2459–2463. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e3181849dbe. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shephard R.J. PAR-Q, Canadian Home Fitness Test and exercise screening alternatives. Sports Med. 1988;5(3):185–195. doi: 10.2165/00007256-198805030-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Franca F.R., Burke T.N., Caffaro R.R., Ramos L.A., Marques A.P. Effects of muscular stretching and segmental stabilization on functional disability and pain in patients with chronic low back pain: a randomized, controlled trial. J Manip Physiol Ther. 2012;35(4):279–285. doi: 10.1016/j.jmpt.2012.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Macedo L.G., Latimer J., Maher C.G. Motor control or graded activity exercises for chronic low back pain? A randomised controlled trial. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2008;9:65. doi: 10.1186/1471-2474-9-65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Smeets R.J., Vlaeyen J.W., Hidding A. Active rehabilitation for chronic low back pain: cognitive-behavioral, physical, or both? First direct post-treatment results from a randomized controlled trial [ISRCTN22714229] BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2006;7:5. doi: 10.1186/1471-2474-7-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Navega M.T., Aveiro M.C., Oishi J. The influence of a physical exercise program on the quality of life in osteoporotic women. Fisioter Mov. 2006;19(4):25–32. [Google Scholar]

- 19.McARDLE E.A. 3rd ed. Guanabara Koogan; São Paulo: 1997. Fisiologia do Treinamento físico. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Roland M., Waddell G., Klaber-Moffett J. The Stationery Office N; United Kingdom: 1996. The Back Book. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Menezes Costa Lda C., Maher C.G., McAuley J.H. The Brazilian-Portuguese versions of the McGill Pain Questionnaire were reproducible, valid, and responsive in patients with musculoskeletal pain. J Clin Epidemiol. 2011;64(8):903–912. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2010.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Souza F.S.d., Marinho C.D., Siqueira F.B., Maher C.G., Costa L.O.P. Psychometric testing confirms that the Brazilian-Portuguese adaptations, the original versions of the Fear-Avoidance Beliefs Questionnaire, and the Tampa Scale of Kinesiophobia have similar measurement properties. Spine. 2008;33(9):1028–1033. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e31816c8329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Florindo A., Latore M. Validação e Reprodutibilidade do questionátio de Baecke de avaliação física habitual em homens adultos. Rev Bras Med Esporte. 2003;9:121–128. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Boonstra A.M., Schiphorst Preuper H.R., Reneman M.F., Posthumus J.B., Stewart R.E. Reliability and validity of the visual analogue scale for disability in patients with chronic musculoskeletal pain. Int J Rehabil Res. 2008;31(2):165–169. doi: 10.1097/MRR.0b013e3282fc0f93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nusbaum L., Natour J., Ferraz M.B., Goldenberg J. Translation, adaptation and validation of the Roland-Morris questionnaire-Brazil Roland-Morris. Braz J Med Biol Res. 2001;34(2):203–210. doi: 10.1590/s0100-879x2001000200007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ciconelli R.M., Feraz M.B., Santos W. Tradução para a língua portuguesa e validação do questionário genérico de avaliação de qualidade de vida SF-36. Rev Bras Reumatol. 1999;39:143–149. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Menezes Costa Lda C., Maher C.G., McAuley J.H., Costa L.O. Systematic review of cross-cultural adaptations of McGill Pain Questionnaire reveals a paucity of clinimetric testing. J Clin Epidemiol. 2009;62(9):934–943. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2009.03.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.de Souza F.S., Marinho Cda S., Siqueira F.B., Maher C.G., Costa L.O. Psychometric testing confirms that the Brazilian-Portuguese adaptations, the original versions of the Fear-Avoidance Beliefs Questionnaire, and the Tampa Scale of Kinesiophobia have similar measurement properties. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2008;33(9):1028–1033. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e31816c8329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Florindo A.A., Latore M.R.D.O. Validação e Reprodutibilidade do questionátio de Baecke de avaliação física habitual em homens adultos. Rev Bras Med Esporte. 2003;9:121–128. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ostelo R.W., Deyo R.A., Stratford P. Interpreting change scores for pain and functional status in low back pain: towards international consensus regarding minimal important change. Spine. 2008;33(1):90–94. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e31815e3a10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.van der Roer N., van Tulder M., Barendse J., Knol D., van Mechelen W., de Vet H. Intensive group training protocol versus guideline physiotherapy for patients with chronic low back pain: a randomised controlled trial. Eur Spine J. 2008;17(9):1193–1200. doi: 10.1007/s00586-008-0718-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Smeets R.J., Vlaeyen J.W., Hidding A., Kester A.D., van der Heijden G.J., Knottnerus J.A. Chronic low back pain: physical training, graded activity with problem solving training, or both? The one-year post-treatment results of a randomized controlled trial. Pain. 2008;134(3):263–276. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2007.04.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hayden J.A., van Tulder M.W., Malmivaara A., Koes B.W. Exercise therapy for treatment of non-specific low back pain. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2005;(3):CD000335. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD000335.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lopez-de-Uralde-Villanueva I., Munoz-Garcia D., Gil-Martinez A. A systematic review and meta-analysis on the effectiveness of graded activity and graded exposure for chronic nonspecific low back pain. Pain Med. 2015 doi: 10.1111/pme.12882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Macedo L.G., Maher C.G., Hancock M.J. Predicting response to motor control exercises and graded activity for patients with low back pain: preplanned secondary analysis of a randomized controlled trial. Phys Ther. 2014;94(11):1543–1554. doi: 10.2522/ptj.20140014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Araujo A.C., da Cunha Menezes Costa L., de Oliveira C.B.S. Measurement properties of the Brazilian-Portuguese Version of the Lumbar Spine Instability Questionnaire. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2017;42(13):E810–E814. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0000000000001977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Haskins R., Osmotherly P.G., Rivett D.A. Diagnostic clinical prediction rules for specific subtypes of low back pain: a systematic review. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2015;45(2):61–76. doi: 10.2519/jospt.2015.5723. A1–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]