Abstract

Background: Staphylococcus aureus, a leading cause of community-acquired and nosocomial infections, remains a major health problem worldwide. Molecular typing methods, such as spa typing, are vital for the control and, when typing can be made more timely, prevention of S. aureus spread around healthcare settings. The current study aims to review the literature to report the most common clinical spa types around the world, which is important for epidemiological surveys and nosocomial infection control policies.

Methods: A search via PubMed, Google Scholar, Web of Science, Embase, the Cochrane library, and Scopus was conducted for original articles reporting the most prevalent spa types among S. aureus isolates. The search terms were “Staphylococcus aureus, spa typing.”

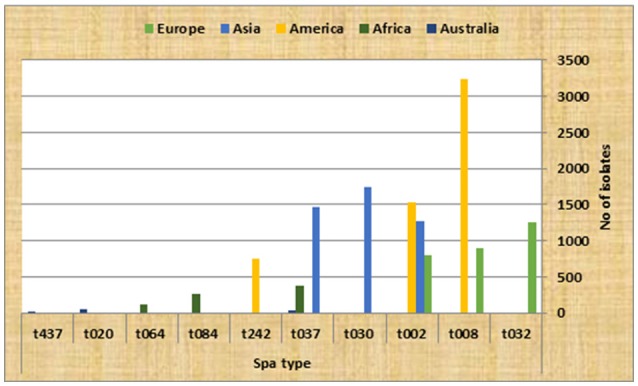

Results: The most prevalent spa types were t032, t008 and t002 in Europe; t037 and t002 in Asia; t008, t002, and t242 in America; t037, t084, and t064 in Africa; and t020 in Australia. In Europe, all the isolates related to spa type t032 were MRSA. In addition, spa type t037 in Africa and t037and t437 in Australia also consisted exclusively of MRSA isolates. Given the fact that more than 95% of the papers we studied originated in the past decade there was no option to study the dynamics of regional clone emergence.

Conclusion: This review documents the presence of the most prevalent spa types in countries, continents and worldwide and shows big local differences in clonal distribution.

Keywords: Staphylococcus aureus, spa typing, MRSA, prevalent, SCCmec typing, MLST, clonal complex

Introduction

Staphylococcus aureus, a leading cause of community-acquired and nosocomial infections, remains a major health problem around the world causing a variety of different conditions including wound infections, osteomyelitis, food poisoning, endocarditis, as well as more life-threatening diseases, such as pneumonia and bacteremia (Goudarzi et al., 2016b). Since the introduction of penicillin into medical therapy in the early 1940s, resistance against beta-lactams started to develop among staphylococcal isolates. To overcome this problem, a narrow spectrum semi-synthetic penicillin (methicillin) was introduced. However, soon after its first use in 1961, the first methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA) strain was identified (Turlej et al., 2011). Methicillin resistance is caused by the mecA gene product, a modified form of penicillin binding protein (PBP), called PBP2a or PBP2', which has a lower affinity for all beta-lactam antibiotics (Hanssen and Ericson Sollid, 2006). The mecA gene is located within the mec operon of the staphylococcal cassette chromosome mec (SCCmec). SCCmec typing, which classifies SCCmec elements on the basis of their structural differences, is applied in several epidemiological studies of MRSA strains (Turlej et al., 2011). Molecular characterization of S .aureus is vital for the rapid identification of prevalent strains and will contribute to the control and prevention of S. aureus spread around healthcare settings if results are provided in real time (Siegel et al., 2007; Bosch et al., 2015; O'Hara et al., 2016). Phage typing was originally used for the formal typing of S. aureus isolates, but it was gradually replaced by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE), the most recent gold standard method for the typing of S. aureus isolates (Bannerman et al., 1995; Murchan et al., 2003; Bosch et al., 2015). However, due to its laborious character and difficulties in exchanging data between laboratories, and the requirement for inter-laboratory standardization, PFGE was replaced by multi-locus sequence typing (MLST) and staphylococcal protein A (spa) typing (Harmsen et al., 2003). MLST is a great tool for evolutionary investigations and differentiates isolates according to nucleotide variations in 7 housekeeping genes. Spa typing, which relies only on the assessment of the number of and sequence variation in repeats at the x region of the spa gene, exhibits excellent discriminatory power and has become a useful typing tool for the sake of its ease of performance, cheaper procedure, and standardized nomenclature (Frenay et al., 1996; Koreen et al., 2004; Strommenger et al., 2008; Bosch et al., 2015; Darban-Sarokhalil et al., 2016; O'Hara et al., 2016). The spa gene contains three distinct regions: Fc, X, and C (Verwey, 1940; Harmsen et al., 2003; Goudarzi et al., 2016b). The polymorphic X region, which encodes a part of the staphylococcal protein A (Spa), contains variations in the number of tandem repeats and the base sequence within each repeat. In other words, each new sequence motif, with a length of 24 bp, found in any S. aureus strain is assigned a unique repeat code and the repeat succession and the precise sequences of the individual repeats for a given strain determines its spa type (Mazi et al., 2015). The primary binding site for protein A is the Fc region of mammalian immunoglobulins, most notably IgGs, which renders the bacteria inaccessible to opsonins, thus impairing phagocytosis by immune system attack (Graille et al., 2000).

According to the literature, the prevalence of spa types among S. aureus isolates varies in different areas around the world. According to the authors' knowledge, no comprehensive data, during the last decade, have been made available on the distribution of diverse spa types within different geographical areas, so the aim of the present study was to review the literature to report the most common clinical spa types which is important for discriminating S. aureus outbreak isolates and nosocomial infection control policies worldwide.

SeqNet.org has shown the 10 most frequent spa types on the seqNet during 2004–2008 which includes only the European countries plus Lebanon. These data seem to include MRSA from both human and veterinary sources which is different from the present review which includes only human clinical data and a larger geographic domain.

Methods

Search strategy and selection criteria

The PubMed, Google Scholar, Web of Science, Embase, Cochrane library, and Scopus databases were searched for original articles, reporting regionally prevalent spa types among S. aureus isolates. The search terms were “Staphylococcus aureus, spa typing.”

The articles were selected according to evaluations on titles, abstracts and the main text. The reasons for exclusion of certain articles were: non-human clinical isolates of S. aureus, old spa-typing methods (e.g., RFLP), non-English articles, and isolates from patients with certain specific diseases including HIV and other immune mediated afflictions. Following main text assessment, several articles were excluded for unspecified sample size or the lack of a predominant spa type in the study. Studies presented only in abstract form were also excluded. Papers occurring in more than a single database were cited once.

Data extraction

The following data were extracted from each article: first author's name, year of publication, country, number of isolates, number of methicillin resistant and susceptible S. aureus isolates (MRSA and MSSA), the predominant spa type, SCCmec types of the predominant spa types, MLST and spa clonal complexes belonging to the most prevalent spa types.

Results

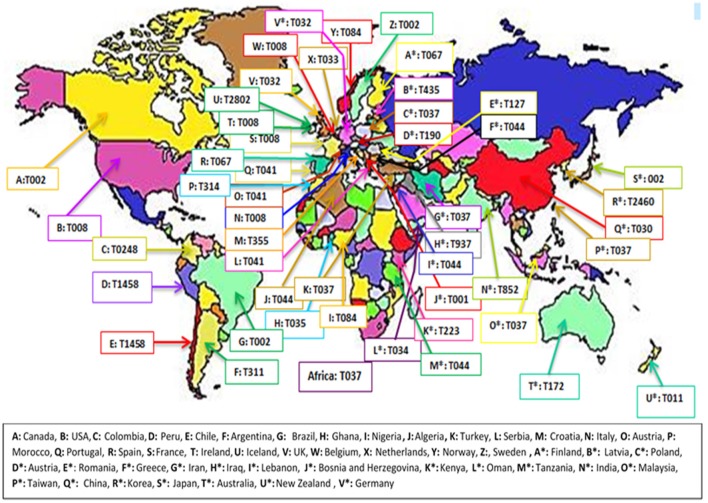

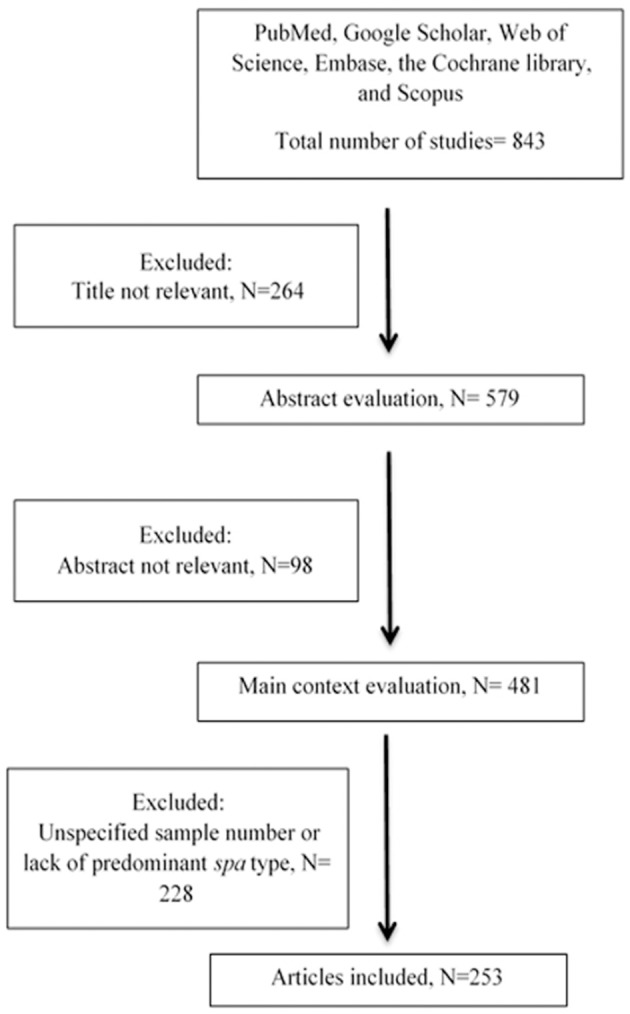

During the initial database search, a total of 843 articles, from 5 continents (Europe, Asia, America, Africa and Australia), were collected among which 264 and 98 were excluded based on title and abstract evaluations, respectively (Figure 1). Out of the remaining articles, 253 fulfilled our inclusion criteria (Shopsin et al., 1999; Graille et al., 2000; Fey et al., 2003; Arakere et al., 2005; Denis et al., 2005; Ko et al., 2005; Aires-de-Sousa et al., 2006, 2008; Deplano et al., 2006; Durand et al., 2006; Ferry et al., 2006, 2010; Fossum and Bukholm, 2006; Jury et al., 2006; Kuhn et al., 2006; Mellmann et al., 2006, 2008; Montesinos et al., 2006; Ruppitsch et al., 2006, 2007; Sabat et al., 2006; Cai et al., 2007, 2009; Conceicao et al., 2007; Cookson et al., 2007; Ellington et al., 2007a,b; Ghebremedhin et al., 2007; Hallin et al., 2007, 2008; Krasuski et al., 2007; Matussek et al., 2007; Otter et al., 2007; Tristan et al., 2007; Van Loo et al., 2007; Vourli et al., 2007; Werbick et al., 2007; Witte et al., 2007; von Eiff et al., 2007; Bartels et al., 2008, 2013, 2014; Chaberny et al., 2008; Chmelnitsky et al., 2008; Gardella et al., 2008; Fenner et al., 2008a,b; Golding et al., 2008, 2011; Ho et al., 2008a,b, 2012, 2016, 2017; Jappe et al., 2008; Karynski et al., 2008; Larsen et al., 2008, 2009; Nulens et al., 2008; Pérez-Vázquez et al., 2008; Strommenger et al., 2008; Vainio et al., 2008, 2011; Zhang et al., 2008, 2009; Alp et al., 2009; Argudín et al., 2009, 2011; Atkinson et al., 2009; Bekkhoucha et al., 2009; Chen et al., 2009; Chen H.-J. et al., 2010; Chen L. et al., 2010; Chen et al., 2012, 2013, 2014; Croes et al., 2009; Khandavilli et al., 2009; Köck et al., 2009; Lamaro-Cardoso et al., 2009; Lindqvist et al., 2009, 2012, 2015; Liu et al., 2009, 2010; Melin et al., 2009; Peck et al., 2009; Rasschaert et al., 2009; Rijnders et al., 2009; Shet et al., 2009; Soliman et al., 2009; Sun et al., 2009, 2013; Vindel et al., 2009; Argudin et al., 2010; Borghi et al., 2010; Coombs et al., 2010, 2012; Geng et al., 2010a,b,c; Ghaznavi-Rad et al., 2010; Graveland et al., 2010; Grundmann et al., 2010, 2014; Holzknecht et al., 2010; Ionescu et al., 2010; Laurent et al., 2010; Lee et al., 2010, 2013; Monaco et al., 2010; Moodley et al., 2010; Nadig et al., 2010, 2012; O'Sullivan et al., 2010; Petersson et al., 2010; Raulin et al., 2010; Ruimy et al., 2010; Shore et al., 2010, 2012, 2014; Valaperta et al., 2010; Wang et al., 2010, 2012, 2017; Alvarellos et al., 2011; Babouee et al., 2011; Blanco et al., 2011; Breurec et al., 2011a,b; Boakes et al., 2011; Cheng et al., 2011; Church et al., 2011; Conceição et al., 2011, 2012; García-Álvarez et al., 2011; Hesje et al., 2011; Jansen van Rensburg et al., 2011; Kechrid et al., 2011; Kim et al., 2011; Longtin et al., 2011; Miller et al., 2011; Skråmm et al., 2011; Pfingsten-Würzburg et al., 2011; Sanchini et al., 2011, 2014; Sangvik et al., 2011; Turlej et al., 2011; Ugolotti et al., 2011; Valentin-Domelier et al., 2011; Vandendriessche et al., 2011; Aamot et al., 2012, 2015; Adler et al., 2012; Berktold et al., 2012; Brennan et al., 2012; Cupane et al., 2012; Hafer et al., 2012; Hudson et al., 2012, 2013; Kriegeskorte et al., 2012; Lamand et al., 2012; Lim et al., 2012; Maeda et al., 2012; Marimón et al., 2012; Ngoa et al., 2012; Otokunefor et al., 2012; Ruffing et al., 2012; Sangal et al., 2012; Shambat et al., 2012; Sobral et al., 2012; Velasco et al., 2012; Blumental et al., 2013; Brauner et al., 2013; Camoez et al., 2013; Chroboczek et al., 2013a,b; David et al., 2013; Fernandez et al., 2013; García-Garrote et al., 2013; Gómez-Sanz et al., 2013; He et al., 2013; Japoni-Nejad et al., 2013; Kwak et al., 2013; Li et al., 2013; Lozano et al., 2013; Machuca et al., 2013; Medina et al., 2013; Miko et al., 2013; Murphy et al., 2013; Price et al., 2013; Prosperi et al., 2013; Sabri et al., 2013; Schmid et al., 2013; Song et al., 2013; Tian et al., 2013; Uzunović-Kamberović et al., 2013; van der Donk et al., 2013a,b; Williamson et al., 2013; Xiao et al., 2013; Aiken et al., 2014; Casey et al., 2014; Egyir et al., 2014; Faires et al., 2014; Harastani and Tokajian, 2014; Harastani et al., 2014; Havaei et al., 2014; Holmes et al., 2014; Kachrimanidou et al., 2014; Limbago et al., 2014; Luxner et al., 2014; Mohammadi et al., 2014; Rodríguez et al., 2014; Shakeri and Ghaemi, 2014; Tavares et al., 2014; Udo et al., 2014, 2016; Uzunović et al., 2014; Wiśniewska et al., 2014; Al Laham et al., 2015; Ayepola et al., 2015; Bartoloni et al., 2015; Biber et al., 2015; de Oliveira et al., 2015; Cirković et al., 2015,?; Mirzaii et al., 2015; O'Malley et al., 2015; Perovic et al., 2015; Rajan et al., 2015; Seidl et al., 2015; Shittu et al., 2015; Yu et al., 2015; Darban-Sarokhalil et al., 2016; Dündar et al., 2016; Garcia et al., 2016; Goudarzi et al., 2016a, 2017a,b; Jotić et al., 2016; O'Hara et al., 2016; Omuse et al., 2016; Parhizgari et al., 2016; Ahmed et al., 2017; Amissah et al., 2017; Bayat et al., 2017; Blomfeldt et al., 2017; Chmielarczyk et al., 2017; Gostev et al., 2017; Khemiri et al., 2017; Kong et al., 2017; Múnera et al., 2017; Pomorska-Wesołowska et al., 2017). In total, 127 articles were included from Europe, 70 from Asia, 33 from North and South America, 18 from Africa and 5 from Australia. More than 95% of the articles included in this study were published since 2007 and onwards. The frequent spa types on the different continents are shown in Figures 2, 3 and Table 1. The 3 most prevalent spa types were reported by 14, 33, and 22 out of the 127 studies in Europe, 13, 18, and 18 respective studies out of 70 in Asia, 13, 16, 2 out of 33 in America, and 3, 3, 4 out of 18 studies in Africa. Finally, in Australia, the 3 most prevalent spa types were reported by 1 article each out the total of 5 studies. In total, t202, t037, t437, t172, and t011 were the only spa types reported in Australia.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of literature search and study selection.

Figure 2.

Three most prevalent spa types in Europe, Asia, America, Africa and Australia.

Figure 3.

The most prevalent spa types across the world.

Table 1.

Frequency of the common spa types among different continents.

| Continent | No. of isolates | The most predominant spa types (No. of isolates) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MRSA | MSSA | Uncertified | Total | ||

| Europe | 13,988 | 9,767 | 4,565 | 28,320 | t032 (1,250), t008 (964), t002 (794), t044 (609), t003 (596), t067 (532), t018 (458), t004 (385) |

| Asia | 6,903 | 1,383 | 329 | 8,615 | t030 (2,009), t037 (1,591), t002 (1,277), t437 (351), t1081 (118), t004 (116), t001 (99), t2460 (65) |

| America | 4,828 | 1,126 | 2,187 | 8,141 | t008 (2,100), t002 (1,569), t242 (752), t012 (285), t084 (147), t003 (99), t311 (79), t0149 (74) |

| Africa | 1,223 | 577 | 326 | 2,126 | t037 (394), t084 (267), t064 (123), t1257 (120), t045 (79), t012 (68), t1443 (66), t314 (37) |

| Australia | 148 | 44 | 0 | 192 | t202 (50), t037 (32), t437 (19), t172 (8), t011 (6) |

The Spa server has identified 17625 different spa types until the 17th of December, 20171. Table 2 illustrates the distribution of diverse spa types among various SCCmec types in different continents. In Europe, 52 studies performed SCCmec typing on 3208 spa types and SCCmec types IV (1830 isolates) and II (800 isolates) were most associated and SCCmec type V (126 isolates) was least associated with the most common spa types. In Asia, SCCmec typing was performed on 4179 spa types by 41 studies and the most common spa types were classified into SCCmec types III (2725 isolates) and II (677 isolates), whilst the least number of spa types were categorized into SCCmec type V (104 isolates). A total of 12 studies in America performed SCCmec typing on 531 spa types, showing that SCCmec types IV (238 isolates) and II (167 isolates) were most associated with the frequent spa types. In Africa, 5 studies assessed the SCCmec types of 615 spa types and the common spa types were classified into SCCmec types IV (217 isolates) and V (185 isolates) whilst the least number of spa types were categorized into SCCmec type I (37 isolates). Finally, in Australia SCCmec typing was performed on 107 spa types by 5 studies and the most common spa types were classified into SCCmec types IV (49 isolates) and III (40 isolates), whilst the least number of spa types were categorized into SCCmec type I and II.

Table 2.

Distribution of diverse spa types among various SCCmec types in different continents.

| Continent | Spa types associated with SCCmec types (No.) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type I | Type II | Type III | Type IV | Type V | |

| Europe | t041 (189), t744 (8), t2023 (11), t002 (6), t022 (7), ?* (71) | t018 (369), t003 (33), t002 (113), t004 (196), ?* (89) | t037 (58), ?* (102) | t032 (375), t008 (328), t067 (314), t019 (66), t2802 (37), t044 (164), t002 (49), t051 (10), t038 (7), t744 (8), t304 (31), t005 (32), t515 (18), t148 (14), t024 (42), t022 (12), t127 (61), t189 (4), t030 (11), ?* (247) | t011 (60), t034 (31), t108 (11), t657 (23), t019 (1) |

| Asia | t127 (1), t2460 (1), t701 (2), t002 (8), t030 (3), t001 (99) | t002 (637), t2460 (36), t030 (4) | t037 (635), t071 (11), t030 (415), t002 (258), ?* (1,406) | t852 (44), t190 (7), t127 (6), t002 (23), t324 (13), t008 (31), t437 (94), t796 (3), t318 (12), t991 (12), ?* (203) | t701 (1), t002 (10), t030 (11), t081 (40), t437 (18), t657 (21), ?* (3) |

| America | t149 (25), t149 (18) | t002 (44), t008 (3), ?* (120) | t459 (29), t037 (7), ?* (47) | t084 (135), t002 (3), t008 (38), t045 (3), t019 (23), t024 (25), t216 (6), ?* (5) | – |

| Africa | t045 (37) | t311 (2), t012 (68) | t037 (106) | t044 (17), t311 (18), t186 (15), t064 (68), t1443 (66), t2196 (33) | t037 (1), t311 (1), ?* (183) |

| Australia | – | – | t172 (8), t037 (32) | t437 (7), t202 (42) | t437 (12), t011 (6) |

Unknown spa type.

The total number of MRSA and MSSA isolates of the 3 most common spa types among different continents are shown in Table 3. In Europe, all the isolates related to spa type t032 were MRSA. In addition, spa type t037 in Africa and t037 and t437 in Australia were MRSA as well.

Table 3.

Total number of MRSA and MSSA isolates of the most common spa types among different continents.

| Continent | The most common spa types (No.): No. of MRSA and/or MSSA isolates | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Europe | t032 (1,250): 1250 MRSA | t008 (899): 510 MRSA, 229 MSSA, 90 uncertified | t002 (794): 450 MRSA, 100 MSSA, 244 uncertified |

| Asia | t030 (1,748): 1686 MRSA, 51 MSSA, 11uncertified | t037 (1,467): 1415 MRSA, 51 MSSA, 1 uncertified | T002 (1,285): 8064 MRSA, 9 MSSA, 340 uncertified |

| America | t008 (2,100): 2151 MRSA, 56 MSSA, 107 uncertified | t002 (1,525): 855 MRSA, 80 MSSA, 857 uncertified | t242 (752):478 MRSA, 274 uncertified |

| Africa | t037 (381): 381 MRSA | t084 (267): 217MSSA, 50 uncertified | t064 (123): 256 MRSA, 11 uncertified |

| Australia | t202 (50): 50 uncertified | t037 (32): 32 MRSA | t437 (19): 19 MRSA |

MRSA, methicillin resistant Staphylococcus aureus; MSSA, methicillin sensitive Staphylococcus aureus; Uncertified, not mentioned in the studies whether the isolates were MRSA or MSSA.

Spa clonal complex (S-CC) and MLST clonal complex (M-CC), plus the sequence types (STs) of the most common spa types among different continents are illustrated in Table 4. The number of studies that reported spa clonal complex for the common spa types were 30 in Europe, 12 in Asia, 10 in America and 9 in Africa. Common spa types categorized into distinct MLST clonal complexes were 43 in Europe, 19 in Asia, 14 in America, and 9 in Africa. Forty eight studies in Europe, 29 in Asia, 18 in America, and 11 studies in Africa assessed the sequence types of the most common spa types. In Australia, no studies reported the spa or MLST complexes, nor any sequence types for the common spa types assessed.

Table 4.

Spa and MLST clonal complexes plus sequence types of the most common spa types among different continents.

| Continent | Prevalent spa types (No. of isolates) | Spa clonal complex/ S-CC (No. of spa types) | MLST clonal complex/M-CC (No. of spa types) | Sequence type/ST (No. of spa types) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Europe | t032 (1,250) t008 (899) t002 (794) |

– S-CC008 (22) S-CC002 (58) |

M-CC22 (97) M-CC8 (57) M-CC5 (162) |

ST22 (173) ST8 (295), ST247 (51) ST5 (186) |

| Asia | t030 (1,748) t037 (1,467) t002 (1,285) |

S-CC030 (121) S-CC001 (111) S-CC002 (431), SCC001/002 (8) |

M-CC59 (11), M-CC8 (159) M-CC8 (198), M-CC5 (8), M-CC 188 (16) M-CC5 (145), M-CC8 (157) |

ST239 (1,422), ST22 (99) ST 239 (1,124) ST5 (459) |

| America | t008 (2,100) t002 (1,525) t242 (752) |

S-CC008 (97) S-CC002 (53) – |

M-CC 85 (85), M-CC5 (5) M-CC5 (30), M-CC8 (5) – |

ST8 (524), ST247 (100) ST5 (701) – |

| Africa | t037 (381) t084 (267) t064 (123) |

– S-CC84 (75) S-CC64 (68) |

M-CC239 (30) M-CC15 (75) M-CC8 (10), M-CC30 (68) |

ST 239 (173) ST 15 (60) ST8 (68) |

| Australia | t202 (50) t037 (32) t437 (19) |

– – – |

– – – |

– – – |

The association of the most prevalent spa types with different countries among different continents is shown by Table S1 in Supplementary Material. The data exhibit that The Netherlands has reported the most diverse range of spa types (34 types), followed by China (22 spa types), Germany (16 types), UK (15 types), Spain (11 types), Sweden and USA (10 spa types each), Italy and Iran (8 spa types each), France and Portugal (7 spa types each) and Switzerland (6 spa types).

Dissemination of different spa types among different countries is illustrated by Table S2 in Supplementary Material. The spa types t008 and t002 were the most frequently repeated spa types among the others, each repeated in 16 countries among different continent. The next most frequently repeated spa types were respectively t037 (12 countries), t044 (11 countries), t084 (8 countries), t012 and 127 (7 countries each), t041 (6 countries), and t019, t011, t034, t355, t189, t304 (5 countries each). Almost 50% of the spa types (43 out of the 87) were only reported by 1 country.

Discussion

Staphylococcus aureus is capable of adapting to a variety of conditions and successful clones can be epidemic and even pandemic as can be concluded by their spreading from one continent to another (Parhizgari et al., 2016). The current review reports the prevalence of spa types among clinical isolates, both as carriage and infectious isolates, across the world. Our analysis showed that t032 was the most prevalent spa type in Europe, predominantly centered in the UK and Germany (Figure 3), and among the 5 most predominant spa types in Austria. No other countries in Europe have reported t032 among its most frequent spa types. Moreover, t008 was the second most prevalent and, nonetheless, the most frequently identified spa type in the various European countries, distributed among 11 out of the 22 of them investigating local spa types while also being the predominant type in France and Italy (Table S2 in Supplementary Material). Germany and UK principally provided a larger sample size compared to other European countries, looking over 10081 and 2644 isolates, respectively. Despite the fact that a larger sample size could be a proof to the validity of acquired data, it might also be that the disparity of the sample size among different countries has caused deviance in the report of the most prevalent spa type in Europe by the present study. Sweden appeared to be the only European country to have t002 as its most predominant spa type, even though t002 was disseminated in 9 out of the 22 European countries included in this analysis. A comprehensive molecular-epidemiological analysis, investigating the geographical distribution of invasive S. aureus isolates in Europe (Grundmann et al., 2010), revealed that the 3 most common spa types in Europe were t032, t008, and t002, respectively; which was in agreement with the results of the current meta-analysis. In Asia, t030 was the predominant spa type mainly located in China (Figure 3), while also reported by Iran as the fifth most common spa type. Moreover, t037, as the second most common spa type in Asia, was reported by more Asian countries compared to other spa types (Korea, China, Taiwan, Iran and Malaysia out of 10 Asian countries under this survey). Similarly in Africa, t037 was the most prevalent and t084 and t064 the most frequently repeated spa types, reported by 3 African countries each. Even though t008 was the most prevalent spa type in America, it was only reported by the USA and Canada. Then again, t002, as the second most common spa type was distributed among the USA, Canada and Brazil. Again, for these 3 continents the distinct sample size variation within the conforming countries might account for the different reports of the prevalent spa types among the associated continents. In Australia no precise information was revealed about the distribution of spa types.

The spa typing method, although being one of the valid schemes for the epidemiological surveillance of S. aureus, only considers a very limited portion of the whole genome and, therefore, could not possibly reflect the mutational events occurring in other parts of this organism's genome. Since certain spa types are still restricted to particular geographic locations, it might be considered that the polymorphic X region and, hence, the type of protein A have possible associations with the organism's adaptations to diverse conditions such as different host populations, the weather and geographical diversity.

As a vital virulence factor which enables the escape of S. aureus from innate and adaptive immune responses, the Spa protein may be an important target for adaptive evolution by means of host specialization and other environmental factors (Santos-Júnior et al., 2016). The plasticity of the spa gene, as a result of intragenic recombination, non-synonymous mutations as well as duplications events, can indeed influence the pathogenicity of S. aureus1. It has been shown that the mosaic spa gene is composed of different segments, each with a distinct evolutionary histories which could provide S. aureus with increased fitness to colonize the host surfaces or bind the immunoglobulin subunits. This diversity of Spa domains has contributed to the epidemic phenotype of S. aureus strains implying that they represent selected adaptations to their environment (Santos-Júnior et al., 2016).

Considering the fact that the primary binding site for protein A is the Fc region of mammalian immunoglobulins, and most notably IgGs (Graille et al., 2000), one possible justification for such an association might be the likely difference in the incidence rates of immunoglobulin subclasses among different geographical populations and, hence, the different binding strength of protein A types to these immunoglobulins. This might consequently cause a difference in the extent of opsonization and phagocytosis and, hence, the survival rates of particular S. aureus spa types within different populations (Sasso et al., 1991)2.

Overall, t008 (2692 MRSA, 258 MSSA, 222 uncertified) and t002 (9364 MRSA, 189 MSSA and 1441 uncertified) were the most widely distributed spa types worldwide, disseminated each through 16 out of the 34 countries assessing spa types, followed by t037 (1971 MRSA, 51 MSSA, 62 uncertified) and t044 (590MRSA, 0 MSSA, 77 uncertified) respectively occurring in 12 and 11 countries worldwide. Almost half of the spa types (43 out of the 87) were yet localized and limited to 1 country each (Table S2 in Supplementary Material). Migrations from one country/continent to another provides a reasonable justification as to why some spa types are common between certain countries/continents. In Europe, all the isolates related to spa type t032 were MRSA isolates. In addition, spa type t037 in Africa and t037and t437 in Australia consisted only of MRSA isolates; however, as shown in Table 3, the majority of predominant spa types consist of both MRSA and MSSA isolates (Adler et al., 2012; Jiménez et al., 2013; Aiken et al., 2014). Here again, a notable number of studies have not deduced whether the predominant spa types are MRSA or MSSA and there is therefore some missing points in the data regarding the association of prevalent spa types and methicillin resistance among different continents. Furthermore, results are dependent on the original sample collection to be spa typed. Most studies have, in the first place, spa typed methicillin resistant S. aureus isolates because of their epidemiological importance among clinical settings (Ruppitsch et al., 2006; Zhang et al., 2008; Miller et al., 2011) and therefore no specific conclusion is to be invoked as to whether MRSA/MSSA isolates belong to specific spa types or vice versa.

In Europe, SCCmec types IV and II were most associated with the common spa types. In Asia, the most common spa types were classified into SCCmec types III and II. In America, SCCmec types IV and II were most associated with frequent spa types. In Africa, the common spa types were classified into SCCmec types IV and V and finally, in Australia the most common spa types were classified into SCCmec types IV and III. The spa and SCCmec typing methods focus on two distinct locations within the genome of S. aureus. The last SCCmec type reported in 2015 in Germany was the SCCmec type XII (Wu et al., 2015), whereas the studies assessed in this review, have only ascertained limited SCCmec types (I, II, II, IV, and V). Moreover, a significant number of spa types have not been associated to any specific SCCmec type and the number of studies which have assessed SCCmec typing for the prevalent spa types are limited. For the above mentioned reasons, the association between certain spa and SCCmec types found in this review might be of questionable reliability.

Data relating to the spa and MLST clonal complexes, and sequence types of the most common spa types revealed that the spa clonal complexes (S-CC) 001 and 002 were common among Europe and Asia and had the highest association with prevalent spa types in this continents. Similarly, S-CC012 contained some frequent spa types reported by Europe, America and Africa while S-CC84 was only common among America and Africa. This means that some related spa types exist among different continents. On the other hand, MLST clonal complex (M-CC) 5 was associated with prevalent spa types in Europe, Asia, America and Africa. Meanwhile, some of the most frequently encountered spa types were associated to M-CC 8 which were common among Asia, America and Africa. It seems that there is a virtually sustained association between the spa and sequence types irrelevant of the continent. For example, t032 has almost always been associated with ST22 across all continents; the same is true for t008 which has been associated with either ST8 or ST247, among all the studies being assessed in this review. As some of the most prevalent spa types reported by many different studies, t002, t030, and t037 have been constantly associated with ST5; ST239 and ST22; and ST239, respectively. In Australia, no studies reported the spa, MLST complexes or sequence types for the common spa types assessed. S. aureus, as an organism with a relatively stable genome, tends to present as clones which are relatively stable and generally diversify by the accumulation of single nucleotide substitutions without frequent inter-strain recombination (Grundmann et al., 2010; Shittu et al., 2011; van der Donk et al., 2013b). It is also noteworthy to mention that S. aureus clones might vary among different clinical settings within the same country or even among different wards of the same hospital (Shittu et al., 2011; van der Donk et al., 2013b; Seidl et al., 2015). Since a majority of studies under this review did not specifically discern the exact location of sampling, the data presented in this review presents a general information about the prevalent spa types and the associated clonal complexes in each country/continent; so, it would have been valuable to provide information on the exact sampling time and location within each country among different continents.

Conclusion

This review shows the spread of the most prevalent spa types in countries, continents and worldwide. Such data can be used for epidemiological purposes, such as defining the geographical spread of the predominant spa types of S. aureus, the interpretation of relative frequencies, comparing the worldwide diverse evolutionary trajectories of S. aureus lineages, and the understanding of molecular epidemiological dynamics of S. aureus transmission.

Author contributions

DD-S designed the first concept, helped in the literature review, data extraction, and preparation of the manuscript. PA prepared the manuscript, interpreted the data, and helped in the literature review and data extraction. NF helped in the literature review and data extraction. MM, SSK, and MD participated in the manuscript preparation. AvB made critical revision and helped in the preparation of the manuscript. KA helped in the analysis, interpretation of data, and preparation of the manuscript. All authors read and confirmed the content of the paper.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Footnotes

1Ridom Gmb, H., info@ridom.de, Rothgaenger, J., Harmsen, D. Molecular diagnostic differentiation and typing of bacteria - software solutions. (8601); published online Epub(SCHEME = ISO8601) 2003-11-02 (http://www.ridom.de/).

2G. healthcare. (http://www.gelifesciences.com), pp. DF-1.6 %âãÏÓ 1333 1330 obj <</Linearized 1331/L 3256349/O 3251336/E 3272957/N 3256173/T 3254047/H [3256516 3251548]>> endobj 3251354 3256340 obj <</DecodeParms <</Columns 3256344/Predictor 3256312>>/Filter/ FlateDecode/ID[ <3256387AC3256329D3256370FC3256363F3256344D3256 345CCEBFB3256374F3256335F3256811> <3256819D3256377F3256347 F3829348BEF3256342C3256343C3256931C3256359C3256346F>]/Index[325 1333 3256336]/Info 3251332 3256340 R/Length 3256100/Prev 3254048/Root 3251334 3256340 R/Size 3251369/Type/XRef/W[3256341 3256342 3256341]>>stream hÞbbd “bà”.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fmicb.2018.00163/full#supplementary-material

References

- Aamot H. V., Blomfeldt A., Eskesen A. N. (2012). Genotyping of 353 Staphylococcus aureus bloodstream isolates collected between 2004 and 2009 at a Norwegian university hospital and potential associations with clinical parameters. J. Clin. Microbiol. 50, 3111–3114. 10.1128/JCM.01352-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aamot H., Stavem K., Skråmm I. (2015). No change in the distribution of types and antibiotic resistance in clinical Staphylococcus aureus isolates from orthopaedic patients during a period of 12 years. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 34, 1833–1837. 10.1007/s10096-015-2420-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adler A., Chmelnitsky I., Shitrit P., Sprecher H., Navon-Venezia S., Embon A., et al. (2012). Molecular epidemiology of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in Israel: dissemination of global clones and unique features. J. Clin. Microbiol. 50, 134–137. 10.1128/JCM.05446-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed M. O., Baptiste K. E., Daw M. A., Elramalli A. K., Abouzeeda Y. M., Petersen A. (2017). Spa typing and identification of pvl genes of meticillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus isolated from a Libyan hospital in Tripoli. J. Global Antimicrob. Resist. 10, 179–181. 10.1016/j.jgar.2017.06.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aiken A. M., Mutuku I. M., Sabat A. J., Akkerboom V., Mwangi J., Scott J. A. G., et al. (2014). Carriage of Staphylococcus aureus in Thika Level 5 Hospital, Kenya: a cross-sectional study. Antimicrob. Resist. Infect. Control 3:22. 10.1186/2047-2994-3-22 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aires-de-Sousa M., Conceicao T. D., De Lencastre H. (2006). Unusually high prevalence of nosocomial Panton-Valentine leukocidin-positive Staphylococcus aureus isolates in Cape Verde Islands. J. Clin. Microbiol. 44, 3790–3793. 10.1128/JCM.01192-06 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aires-de-Sousa M., Correia B., de Lencastre H. (2008). Changing patterns in frequency of recovery of five methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus clones in Portuguese hospitals: surveillance over a 16-year period. J. Clin. Microbiol. 46, 2912–2917. 10.1128/JCM.00692-08 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Al Laham N., Mediavilla J. R., Chen L., Abdelateef N., Elamreen F. A., Ginocchio C. C., et al. (2015). MRSA clonal complex 22 strains harboring toxic shock syndrome toxin (TSST-1) are endemic in the primary hospital in Gaza, Palestine. PLoS ONE 10:e0120008. 10.1371/journal.pone.0120008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alp E., Klaassen C. H., Doganay M., Altoparlak U., Aydin K., Engin A., et al. (2009). MRSA genotypes in Turkey: persistence over 10 years of a single clone of ST239. J. Infect. 58, 433–438. 10.1016/j.jinf.2009.04.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alvarellos C. P., Carames L. C., Castro S. P., Garcia P. A., Pi-on J. T., Fernandez M. A. (2011). Usefulness of the restriction–modification test plus staphylococcal cassette chromosome mec types and Panton–Valentine leukocidin encoding phages to identify Staphylococcus aureus methicillin-resistant clones. Scand. J. Infect. Dis. 43, 943–946. 10.3109/00365548.2011.589078 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amissah N. A., van Dam L., Ablordey A., Ampomah O.-W., Prah I., Tetteh C. S., et al. (2017). Epidemiology of Staphylococcus aureus in a burn unit of a tertiary care center in Ghana. PLoS ONE 12:e0181072. 10.1371/journal.pone.0181072 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arakere G., Nadig S., Swedberg G., Macaden R., Amarnath S. K., Raghunath D. (2005). Genotyping of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus strains from two hospitals in Bangalore, South India. J. Clin. Microbiol. 43, 3198–3202. 10.1128/JCM.43.7.3198-3202.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Argudín M. A., Mendoza M. C., Vazquez F., Guerra B., Rodicio M. R. (2011). Molecular typing of Staphylococcus aureus bloodstream isolates from geriatric patients attending a long-term care Spanish hospital. J. Med. Microbiol. 60, 172–179. 10.1099/jmm.0.021758-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Argudin M., Fetsch A., Tenhagen A.-B., Hammerl J., Hertwig S., Schroeter A., et al. (2010). High heterogeneity within methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus ST398 isolates, defined by Cfr9I macrorestriction-pulsed-field gel electrophoresis profiles and spa and SCCmec types. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 76, 652–658. 10.1128/AEM.01721-09 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Argudín M., Mendoza M., Méndez F., Martín M., Guerra B., Rodicio M. (2009). Clonal complexes and diversity of exotoxin gene profiles in methicillin-resistant and methicillin-susceptible Staphylococcus aureus isolates from patients in a Spanish hospital. J. Clin. Microbiol. 47, 2097–2105. 10.1128/JCM.01486-08 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atkinson S., Paul J., Sloan E., Curtis S., Miller R. (2009). The emergence of meticillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus among injecting drug users. J. Infect. 58, 339–345. 10.1016/j.jinf.2009.03.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ayepola O. O., Olasupo N. A., Egwari L. O., Becker K., Schaumburg F. (2015). Molecular characterization and antimicrobial susceptibility of Staphylococcus aureus isolates from clinical infection and asymptomatic carriers in Southwest Nigeria. PLoS ONE 10:e0137531. 10.1371/journal.pone.0137531 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babouee B., Frei R., Schultheiss E., Widmer A., Goldenberger D. (2011). Comparison of the DiversiLab repetitive element PCR system with spa typing and pulsed-field gel electrophoresis for clonal characterization of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. J. Clin. Microbiol. 49, 1549–1555. 10.1128/JCM.02254-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bannerman T. L., Hancock G. A., Tenover F. C., Miller J. M. (1995). Pulsed-field gel electrophoresis as a replacement for bacteriophage typing of Staphylococcus aureus. J. Clin. Microbiol. 33, 551–555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartels M. D., Boye K., Oliveira D. C., Worning P., Goering R., Westh H. (2013). Associations between dru types and SCCmec cassettes. PLoS ONE 8:e61860. 10.1371/journal.pone.0061860 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartels M. D., Nanuashvili A., Boye K., Rohde S. M., Jashiashvili N., Faria N., et al. (2008). Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in hospitals in Tbilisi, the Republic of Georgia, are variants of the Brazilian clone. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 27:757. 10.1007/s10096-008-0500-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartels M. D., Petersen A., Worning P., Nielsen J. B., Larner-Svensson H., Johansen H. K., et al. (2014). Comparing whole-genome sequencing with Sanger sequencing for spa typing of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. J. Clin. Microbiol. 52, 4305–4308. 10.1128/JCM.01979-14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartoloni A., Riccobono E., Magnelli D., Villagran A. L., Di Maggio T., Mantella A., et al. (2015). Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in hospitalized patients from the Bolivian Chaco. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 30, 156–160. 10.1016/j.ijid.2014.12.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bayat B., Zade M. H., Mansouri S., Kalantar E., Kabir K., Zahmatkesh E., et al. (2017). High frequency of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) with SCC mec type III and spa type t030 in Karaj's teaching hospitals, Iran. Acta Microbiol. Immunol. Hung. 64, 1–11. 10.1556/030.64.2017.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bekkhoucha S., Cady A., Gautier P., Itim F., Donnio P.-Y. (2009). A portrait of Staphylococcus aureus from the other side of the Mediterranean Sea: molecular characteristics of isolates from Western Algeria. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 28:553. 10.1007/s10096-008-0660-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berktold M., Grif K., Mäser M., Witte W., Würzner R., Orth-Höller D. (2012). Genetic characterization of Panton–Valentine leukocidin-producing methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in Western Austria. Wien. Klin. Wochenschr. 124, 709–715. 10.1007/s00508-012-0244-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biber A., Parizade M., Taran D., Jaber H., Berla E., Rubin C., et al. (2015). Molecular epidemiology of community-onset methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infections in Israel. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 34, 1603–1613. 10.1007/s10096-015-2395-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanco R., Tristan A., Ezpeleta G., Larsen A. R., Bes M., Etienne J., et al. (2011). Molecular epidemiology of Panton-Valentine leukocidin-positive Staphylococcus aureus in Spain: emergence of the USA300 clone in an autochthonous population. J. Clin. Microbiol. 49, 433–436. 10.1128/JCM.02201-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blomfeldt A., Larssen K., Moghen A., Gabrielsen C., Elstrøm P., Aamot H., et al. (2017). Emerging multidrug-resistant Bengal Bay clone ST772-MRSA-V in Norway: molecular epidemiology 2004–2014. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 36, 1911–1192. 10.1007/s10096-017-3014-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blumental S., Deplano A., Jourdain S., De Mendonça R., Hallin M., Nonhoff C., et al. (2013). Dynamic pattern and genotypic diversity of Staphylococcus aureus nasopharyngeal carriage in healthy pre-school children. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 68, 1517–1523. 10.1093/jac/dkt080 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boakes E., Kearns A., Ganner M., Perry C., Warner M., Hill R., et al. (2011). Molecular diversity within clonal complex 22 methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus encoding Panton–Valentine leukocidin in England and Wales. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 17, 140–145. 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2010.03199.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borghi E., Cainarca M., Sciota R., Biassoni C., Morace G. (2010). Molecular picture of community-and healthcare-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus circulating in a teaching hospital in Milan. Scand. J. Infect. Dis. 42, 873–878. 10.3109/00365548.2010.508465 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bosch T., Pluister G. N., Van Luit M., Landman F., van Santen-Verheuvel M., Schot C., et al. (2015). Multiple-locus variable number tandem repeat analysis is superior to spa typing and sufficient to characterize MRSA for surveillance purposes. Future Microbiol. 10, 1155–1162. 10.2217/fmb.15.35 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brauner J., Hallin M., Deplano A., De Mendonça R., Nonhoff C., De Ryck R., et al. (2013). Community-acquired methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus clones circulating in Belgium from 2005 to 2009: changing epidemiology. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 32, 613–620. 10.1007/s10096-012-1784-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brennan G. I., Shore A. C., Corcoran S., Tecklenborg S., Coleman D. C., O'Connell B. (2012). Emergence of hospital-and community-associated panton-valentine leukocidin-positive methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus genotype ST772-MRSA-V in Ireland and detailed investigation of an ST772-MRSA-V cluster in a neonatal intensive care unit. J. Clin. Microbiol. 50, 841–847. 10.1128/JCM.06354-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breurec S., Fall C., Pouillot R., Boisier P., Brisse S., Diene-Sarr F., et al. (2011a). Epidemiology of methicillin-susceptible Staphylococcus aureus lineages in five major African towns: high prevalence of Panton–Valentine leukocidin genes. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 17, 633–639. 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2010.03320.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breurec S., Zriouil S., Fall C., Boisier P., Brisse S., Djibo S., et al. (2011b). Epidemiology of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus lineages in five major African towns: emergence and spread of atypical clones. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 17, 160–165. 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2010.03219.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai L., Kong F., Wang Q., Wang H., Xiao M., Sintchenko V., et al. (2009). A new multiplex PCR-based reverse line-blot hybridization (mPCR/RLB) assay for rapid staphylococcal cassette chromosome mec (SCCmec) typing. J. Med. Microbiol. 58, 1045–1057. 10.1099/jmm.0.007955-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai Y., Kong F., Wang Q., Tong Z., Sintchenko V., Zeng X., et al. (2007). Comparison of single-and multilocus sequence typing and toxin gene profiling for characterization of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. J. Clin. Microbiol. 45, 3302–3308. 10.1128/JCM.01082-07 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Camoez M., Sierra J. M., Pujol M., Hornero A., Martin R., Domínguez M. A. (2013). Prevalence and molecular characterization of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus ST398 resistant to tetracycline at a Spanish hospital over 12 years. PLoS ONE 8:e72828. 10.1371/journal.pone.0072828 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casey J. A., Shopsin B., Cosgrove S. E., Nachman K. E., Curriero F. C., Rose H. R., et al. (2014). High-density livestock production and molecularly characterized MRSA infections in Pennsylvania. Environ. Health Perspect. 122:464. 10.1289/ehp.1307370 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaberny I. F., Bindseil A., Sohr D., Gastmeier P. (2008). A point-prevalence study for MRSA in a German university hospital to identify patients at risk and to evaluate an established admission screening procedure. Infection 36, 526–532. 10.1007/s15010-008-7436-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen F.-J., Hiramatsu K., Huang I.-W., Wang C.-H., Lauderdale T.-L. Y. (2009). Panton–Valentine leukocidin (PVL)-positive methicillin-susceptible and resistant Staphylococcus aureus in Taiwan: identification of oxacillin-susceptible mecA-positive methicillin-resistant S. aureus. Diag. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 65, 351–357. 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2009.07.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen H.-J., Hung W.-C., Tseng S.-P., Tsai J.-C., Hsueh P.-R., Teng L.-J. (2010). Fusidic acid resistance determinants in Staphylococcus aureus clinical isolates. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 54, 4985–4991. 10.1128/AAC.00523-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen J. H.-K., Cheng V. C.-C., Chan J. F.-W., She K. K.-K., Yan M.-K., Yau M. C.-Y., et al. (2013). The use of high-resolution melting analysis for rapid spa typing on methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus clinical isolates. J. Microbiol. Methods 92, 99–102. 10.1016/j.mimet.2012.11.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen L., Mediavilla J. R., Smyth D. S., Chavda K. D., Ionescu R., Roberts R. B., et al. (2010). Identification of a novel transposon (Tn6072) and a truncated staphylococcal cassette chromosome mec element in methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus ST239. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 54, 3347–3354. 10.1128/AAC.00001-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X., Yang H.-H., Huangfu Y.-C., Wang W.-K., Liu Y., Ni Y.-X., et al. (2012). Molecular epidemiologic analysis of Staphylococcus aureus isolated from four burn centers. Burns 38, 738–742. 10.1016/j.burns.2011.12.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y., Liu Z., Duo L., Xiong J., Gong Y., Yang J., et al. (2014). Characterization of Staphylococcus aureus from distinct geographic locations in China: an increasing prevalence of spa-t030 and SCCmec type III. PLoS ONE 9:e96255. 10.1371/journal.pone.0096255 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng V., Chan J., Lau E., Yam W., Ho S., Yau M., et al. (2011). Studying the transmission dynamics of meticillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in Hong Kong using spa typing. J. Hosp. Infect. 79, 206–210. 10.1016/j.jhin.2011.03.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chmelnitsky I., Navon-Venezia S., Leavit A., Somekh E., Regev-Yochai G., Chowers M., et al. (2008). SCCmec and spa types of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus strains in Israel. Detection of SCCmec type V. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 27, 385–390. 10.1007/s10096-007-0426-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chmielarczyk A., Pomorska-Wesołowska M., Szczypta A., Romaniszyn D., Pobiega M., Wójkowska-Mach J. (2017). Molecular analysis of meticillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus strains isolated from different types of infections from patients hospitalized in 12 regional, non-teaching hospitals in southern Poland. J. Hosp. Infect. 95, 259–267. 10.1016/j.jhin.2016.10.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chroboczek T., Boisset S., Rasigade J.-P., Tristan A., Bes M., Meugnier H., et al. (2013b). Clonal complex 398 methicillin susceptible Staphylococcus aureus: a frequent unspecialized human pathogen with specific phenotypic and genotypic characteristics. PLoS ONE 8:e68462. 10.1371/journal.pone.0068462 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chroboczek T., Boisset S., Rasigade J. P., Meugnier H., Akpaka P. E., Nicholson A., et al. (2013a). Major West Indies MRSA clones in human beings: do they travel with their hosts? J. Travel Med. 20, 283–288. 10.1111/jtm.12047 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Church D. L., Chow B. L., Lloyd T., Gregson D. B. (2011). Comparison of automated repetitive-sequence–based polymerase chain reaction and spa typing versus pulsed-field gel electrophoresis for molecular typing of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 69, 30–37. 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2010.09.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cirković I., Knežević M., Božić D. D., Rašić D., Larsen A. R., Ðukić S. (2015). Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus biofilm formation on dacryocystorhinostomy silicone tubes depends on the genetic lineage. Graefe's Arch. Clin. Exp. Ophthalmol. 253, 77–82. 10.1007/s00417-014-2786-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conceição T., Aires de Sousa M., Miragaia M., Paulino E., Barroso R., Brito M. J., et al. (2012). Staphylococcus aureus reservoirs and transmission routes in a Portuguese Neonatal Intensive Care Unit: a 30-month surveillance study. Microb. Drug Resist. 18, 116–124. 10.1089/mdr.2011.0182 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conceicao T., Aires-de-Sousa M., Füzi M., Toth A., Paszti J., Ungvári E., et al. (2007). Replacement of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus clones in Hungary over time: a 10-year surveillance study. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 13, 971–979. 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2007.01794.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conceição T., Aires-de-Sousa M., Pona N., Brito M., Barradas C., Coelho R., et al. (2011). High prevalence of ST121 in community-associated methicillin-susceptible Staphylococcus aureus lineages responsible for skin and soft tissue infections in Portuguese children. Eur. J. Clini. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 30, 293–297. 10.1007/s10096-010-1087-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cookson B. D., Robinson D. A., Monk A. B., Murchan S., Deplano A., De Ryck R., et al. (2007). Evaluation of molecular typing methods in characterizing a European collection of epidemic methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus strains: the HARMONY collection. J. Clin. Microbiol. 45, 1830–1837. 10.1128/JCM.02402-06 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coombs G. W., Goering R. V., Chua K. Y., Monecke S., Howden B. P., Stinear T. P., et al. (2012). The molecular epidemiology of the highly virulent ST93 Australian community Staphylococcus aureus strain. PLoS ONE 7:e43037. 10.1371/journal.pone.0043037 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coombs G. W., Monecke S., Ehricht R., Slickers P., Pearson J. C., Tan H. -L., et al. (2010). Differentiation of clonal complex 59 community-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in Western Australia. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 54, 1914–1921. 10.1128/AAC.01287-09 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Croes S., Deurenberg R. H., Boumans M.-L. L., Beisser P. S., Neef C., Stobberingh E. E. (2009). Staphylococcus aureus biofilm formation at the physiologic glucose concentration depends on the S. aureus lineage. BMC Microbiol. 9:229. 10.1186/1471-2180-9-229 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cupane L., Pugacova N., Berzina D., Cauce V., Gardovska D., Miklaševics E. (2012). Patients with Panton-Valentine leukocidin positive Staphylococcus aureus infections run an increased risk of longer hospitalisation. Int. J. Mol. Epidemiol. Genet. 3:48. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darban-Sarokhalil D., Khoramrooz S. S., Marashifard M., Hosseini S. A. A. M., Parhizgari N., Yazdanpanah M., et al. (2016). Molecular characterization of Staphylococcus aureus isolates from southwest of Iran using spa and SCCmec typing methods. Microb. Pathog. 98, 88–92. 10.1016/j.micpath.2016.07.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- David M. Z., Taylor A., Lynfield R., Boxrud D. J., Short G., Zychowski D., et al. (2013). Comparing pulsed-field gel electrophoresis with multilocus sequence typing, spa typing, staphylococcal cassette chromosome mec (SCCmec) typing, and PCR for Panton-Valentine leukocidin, arcA, and opp3 in methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus isolates at a US medical center. J. Clin. Microbiol. 51, 814–819. 10.1128/JCM.02429-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Oliveira L. M., van der Heijden I. M., Golding G. R., Abdala E., Freire M. P., Rossi F., et al. (2015). Staphylococcus aureus isolates colonizing and infecting cirrhotic and liver-transplantation patients: comparison of molecular typing and virulence factors. BMC Microbiol. 15:264. 10.1186/s12866-015-0598-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denis O., Deplano A., De Beenhouwer H., Hallin M., Huysmans G., Garrino M. G., et al. (2005). Polyclonal emergence and importation of community-acquired methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus strains harbouring Panton-Valentine leucocidin genes in Belgium. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 56, 1103–1106. 10.1093/jac/dki379 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deplano A., De Mendonça R., De Ryck R., Struelens M. (2006). External quality assessment of molecular typing of Staphylococcus aureus isolates by a network of laboratories. J. Clin. Microbiol. 44, 3236–3244. 10.1128/JCM.00789-06 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dündar D., Willke A., Sayan M., Koc M. M., Akan O. A., Sumerkan B., et al. (2016). Epidemiological and molecular characteristics of meticillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in Turkey: a multicentre study. J. Global Antimicrob. Resist. 6, 44–49. 10.1016/j.jgar.2016.02.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durand G., Bes M., Meugnier H., Enright M. C., Forey F., Liassine N., et al. (2006). Detection of new methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus clones containing the toxic shock syndrome toxin 1 gene responsible for hospital-and community-acquired infections in France. J. Clin. Microbiol. 44, 847–853. 10.1128/JCM.44.3.847-853.2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egyir B., Guardabassi L., Esson J., Nielsen S. S., Newman M. J., Addo K. K., et al. (2014). Insights into nasal carriage of Staphylococcus aureus in an urban and a rural community in Ghana. PLoS ONE 9:e96119. 10.1371/journal.pone.0096119 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellington M. J., Hope R., Ganner M., Ganner M., East C., Brick G., et al. (2007a). Is Panton–Valentine leucocidin associated with the pathogenesis of Staphylococcus aureus bacteraemia in the UK? J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 60, 402–405. 10.1093/jac/dkm206 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellington M. J., Yearwood L., Ganner M., East C., Kearns A. M. (2007b). Distribution of the ACME-arcA gene among methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus from England and Wales. J. Antimicrobial. Chemother. 61, 73–77. 10.1093/jac/dkm422 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faires M. C., Pearl D. L., Ciccotelli W. A., Berke O., Reid-Smith R. J., Weese J. S. (2014). The use of the temporal scan statistic to detect methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus clusters in a community hospital. BMC Infect. Dis. 14:375. 10.1186/1471-2334-14-375 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fenner L., Widmer A. F., Dangel M., Frei R. (2008a). Distribution of spa types among meticillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus isolates during a 6 year period at a low-prevalence university hospital. J. Med. Microbiol. 57, 612–616. 10.1099/jmm.0.47757-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fenner L., Widmer A., Frei R. (2008b). Molecular epidemiology of invasive methicillin-susceptible Staphylococcus aureus strains circulating at a Swiss University Hospital. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 27, 623–626. 10.1007/s10096-008-0463-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez S., de Vedia L., Furst M. L., Gardella N., Di Gregorio S., Ganaha M., et al. (2013). Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus ST30-SCCmec IVc clone as the major cause of community-acquired invasive infections in Argentina. Infect. Genet. Evol. 14, 401–405. 10.1016/j.meegid.2012.12.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferry T., Bes M., Dauwalder O., Meugnier H., Lina G., Forey F., et al. (2006). Toxin gene content of the Lyon methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus clone compared with that of other pandemic clones. J. Clin. Microbiol. 44, 2642–2644. 10.1128/JCM.00430-06 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferry T., Uckay I., Vaudaux P., Francois P., Schrenzel J., Harbarth S., et al. (2010). Risk factors for treatment failure in orthopedic device-related methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infection. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 29, 171–180. 10.1007/s10096-009-0837-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fey P., Said-Salim B., Rupp M., Hinrichs S., Boxrud D., Davis C., et al. (2003). Comparative molecular analysis of community-or hospital-acquired methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 47, 196–203. 10.1128/AAC.47.1.196-203.2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fossum A., Bukholm G. (2006). Increased incidence of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus ST80, novel ST125 and SCCmecIV in the south-eastern part of Norway during a 12-year period. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 12, 627–633. 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2006.01467.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frenay H., Bunschoten A., Schouls L., Van Leeuwen W., Vandenbroucke-Grauls C., Verhoef J., et al. (1996). Molecular typing of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus on the basis of protein A gene polymorphism. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 15, 60–64. 10.1007/BF01586186 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia C., Acuña-Villaorduña A., Dulanto A., Vandendriessche S., Hallin M., Jacobs J., et al. (2016). Dynamics of nasal carriage of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus among healthcare workers in a tertiary-care hospital in Peru. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 35, 89–93. 10.1007/s10096-015-2512-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- García-Álvarez L., Holden M. T., Lindsay H., Webb C. R., Brown D. F., Curran M. D., et al. (2011). Meticillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus with a novel mecA homologue in human and bovine populations in the UK and Denmark: a descriptive study. Lancet Infect. Dis. 11, 595–603. 10.1016/S1473-3099(11)70126-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- García-Garrote F., Cercenado E., Marín M., Bal M., Trincado P., Corredoira J., et al. (2013). Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus carrying the mecC gene: emergence in Spain and report of a fatal case of bacteraemia. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 69, 45–50. 10.1093/jac/dkt327 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gardella N., von Specht M., Cuirolo A., Rosato A., Gutkind G., Mollerach M. (2008). Community-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus, eastern Argentina. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 62, 343–347. 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2008.07.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geng W., Yang Y., Wang C., Deng L., Zheng Y., Shen X. (2010a). Skin and soft tissue infections caused by community-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus among children in China. Acta Paediatr. 99, 575–580. 10.1111/j.1651-2227.2009.01645.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geng W., Yang Y., Wu D., Huang G., Wang C., Deng L., et al. (2010b). Molecular characteristics of community-acquired, methicillinresistant Staphylococcus aureus isolated from Chinese children. FEMS Immunol. Med. Microbiol. 58, 356–362. 10.1111/j.1574-695X.2009.00648.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geng W., Yang Y., Wu D., Zhang W., Wang C., Shang Y., et al. (2010c). Community-acquired, methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus isolated from children with community-onset pneumonia in China. Pediatr. Pulmonol. 45, 387–394. 10.1002/ppul.21202 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghaznavi-Rad E., Shamsudin M. N., Sekawi Z., Khoon L. Y., Aziz M. N., Hamat R. A., et al. (2010). Predominance and emergence of clones of hospital-acquired methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in Malaysia. J. Clin. Microbiol. 48, 867–872. 10.1128/JCM.01112-09 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghebremedhin B., König W., Witte W., Hardy K., Hawkey P., König B. (2007). Subtyping of ST22-MRSA-IV (Barnim epidemic MRSA strain) at a university clinic in Germany from 2002 to 2005. J. Med. Microbiol. 56, 365–375. 10.1099/jmm.0.46883-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golding G. R., Campbell J. L., Spreitzer D. J., Veyhl J., Surynicz K., Simor A., et al. (2008). A preliminary guideline for the assignment of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus to a Canadian pulsed-field gel electrophoresis epidemic type using spa typing. Can. J. Infect. Dis. Med. Microbiol. 19, 273–281. 10.1155/2008/754249 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golding G. R., Levett P. N., McDonald R. R., Irvine J., Quinn B., Nsungu M., et al. (2011). High rates of Staphylococcus aureus USA400 infection, Northern Canada. Emerging Infect. Dis. 17:722. 10.3201/eid1704.100482 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gómez-Sanz E., Torres C., Lozano C., Zarazaga M. (2013). High diversity of Staphylococcus aureus and Staphylococcus pseudintermedius lineages and toxigenic traits in healthy pet-owning household members. Underestimating normal household contact? Comp. Immunol. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 36, 83–94. 10.1016/j.cimid.2012.10.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gostev V., Kruglov A., Kalinogorskaya O., Dmitrenko O., Khokhlova O., Yamamoto T., et al. (2017). Molecular epidemiology and antibiotic resistance of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus circulating in the Russian Federation. Infect. Genet. Evol. 53, 189–194. 10.1016/j.meegid.2017.06.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goudarzi M., Bahramian M., Tabrizi M. S., Udo E. E., Figueiredo A. M. S., Fazeli M., et al. (2017a). Genetic diversity of methicillin resistant Staphylococcus aureus strains isolated from burn patients in Iran: ST239-SCCmec III/t037 emerges as the major clone. Microb. Pathog. 105, 1–7. 10.1016/j.micpath.2017.02.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goudarzi M., Fazeli M., Goudarzi H., Azad M., Seyedjavadi S. S. (2016b). Spa typing of Staphylococcus aureus strains isolated from clinical specimens of patients with nosocomial infections in Tehran, Iran. Jundishapur J. Microbiol. 9:e35685. 10.5812/jjm.35685 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goudarzi M., Goudarzi H., Figueiredo A. M. S., Udo E. E., Fazeli M., Asadzadeh M., et al. (2016a). Molecular characterization of methicillin resistant Staphylococcus aureus strains isolated from intensive care units in Iran: ST22-SCCmec IV/t790 emerges as the major clone. PLoS ONE 11:e0155529. 10.1371/journal.pone.0155529 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goudarzi M., Seyedjavadi S. S., Nasiri M. J., Goudarzi H., Nia R. S., Dabiri H. (2017b). Molecular characteristics of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) strains isolated from patients with bacteremia based on MLST, SCCmec, spa, and agr locus types analysis. Microb. Pathog. 104, 328–335. 10.1016/j.micpath.2017.01.055 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graille M., Stura E. A., Corper A. L., Sutton B. J., Taussig M. J., Charbonnier J.-B., et al. (2000). Crystal structure of a Staphylococcus aureus protein A domain complexed with the Fab fragment of a human IgM antibody: structural basis for recognition of B-cell receptors and superantigen activity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 97, 5399–5404. 10.1073/pnas.97.10.5399 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graveland H., Wagenaar J. A., Heesterbeek H., Mevius D., Van Duijkeren E., Heederik D. (2010). Methicillin resistant Staphylococcus aureus ST398 in veal calf farming: human MRSA carriage related with animal antimicrobial usage and farm hygiene. PLoS ONE 5:e10990. 10.1371/journal.pone.0010990 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grundmann H., Aanensen D. M., Van Den Wijngaard C. C., Spratt B. G., Harmsen D., Friedrich A. W., et al. (2010). Geographic distribution of Staphylococcus aureus causing invasive infections in Europe: a molecular-epidemiological analysis. PLoS Med. 7:e1000215. 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000215 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grundmann H., Schouls L. M., Aanensen D. M., Pluister G. N., Tami A., Chlebowicz M., et al. (2014). The dynamic changes of dominant clones of Staphylococcus aureus causing bloodstream infections in the European region: results of a second structured survey. Euro Surveill. 19:20987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hafer C., Lin Y., Kornblum J., Lowy F. D., Uhlemann A.-C. (2012). Contribution of selected gene mutations to resistance in clinical isolates of vancomycin-intermediate Staphylococcus aureus. Antimicrobial. Agents chemother. 56, 5845–5851. 10.1128/AAC.01139-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hallin M., Denis O., Deplano A., De Mendonça R., De Ryck R., Rottiers S., et al. (2007). Genetic relatedness between methicillin-susceptible and methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus: results of a national survey. J. Antimicrobial. Chemother. 59, 465–472. 10.1093/jac/dkl535 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hallin M., Denis O., Deplano A., De Ryck R., Crèvecoeur S., Rottiers S., et al. (2008). Evolutionary relationships between sporadic and epidemic strains of healthcare-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 14, 659–669. 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2008.02015.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanssen A. M., Ericson Sollid J. U. (2006). SCCmec in staphylococci: genes on the move. Pathog. Dis. 46, 8–20. 10.1111/j.1574-695X.2005.00009.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harastani H. H., Tokajian S. T. (2014). Community-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus clonal complex 80 type IV (CC80-MRSA-IV) isolated from the Middle East: a heterogeneous expanding clonal lineage. PLoS ONE 9:e103715. 10.1371/journal.pone.0103715 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harastani H. H., Araj G. F., Tokajian S. T. (2014). Molecular characteristics of Staphylococcus aureus isolated from a major hospital in Lebanon. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 19, 33–38. 10.1016/j.ijid.2013.10.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harmsen D., Claus H., Witte W., Rothgänger J., Claus H., Turnwald D., et al. (2003). Typing of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in a university hospital setting by using novel software for spa repeat determination and database management. J. Clin. Microbiol. 41, 5442–5448. 10.1128/JCM.41.12.5442-5448.2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Havaei S. A., Ghanbari F., Rastegari A. A., Azimian A., Khademi F., Hosseini N., et al. (2014). Molecular typing of hospital-acquired Staphylococcus aureus isolated from Isfahan, Iran. 2014, 1–6. Int. Schol. Res. Not. 10.1155/2014/185272 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He W., Chen H., Zhao C., Zhang F., Li H., Wang Q., et al. (2013). Population structure and characterisation of Staphylococcus aureus from bacteraemia at multiple hospitals in China: association between antimicrobial resistance, toxin genes and genotypes. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 42, 211–219. 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2013.04.031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hesje C. K., Sanfilippo C. M., Haas W., Morris T. W. (2011). Molecular epidemiology of methicillin-resistant and methicillin-susceptible Staphylococcus aureus isolated from the eye. Curr. Eye Res. 36, 94–102. 10.3109/02713683.2010.534229 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ho C.-M., Ho M.-W., Lee C.-Y., Tien N., Lu J.-J. (2012). Clonal spreading of methicillin-resistant SCCmec Staphylococcus aureus with specific spa and dru types in central Taiwan. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 31, 499–504. 10.1007/s10096-011-1338-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ho C.-M., Lin C.-Y., Ho M.-W., Lin H.-C., Peng C.-T., Lu J.-J. (2016). Concomitant genotyping revealed diverse spreading between methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus and methicillin-susceptible Staphylococcus aureus in central Taiwan. J. Microbiol. Immunol. Infect. 49, 363–370. 10.1016/j.jmii.2014.07.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ho P.-L., Chuang S.-K., Choi Y.-F., Lee R. A., Lit A. C., Nig T.-L., et al. (2008a). Community-associated methicillin-resistant and methicillin-sensitive Staphylococcus aureus: skin and soft tissue infections in Hong Kong. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 61, 245–250. 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2007.12.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ho P.-L., Lai E. L., Chow K.-H., Chow L. S., Yuen K.-Y., Yung R. W. (2008b). Molecular epidemiology of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in residential care homes for the elderly in Hong Kong. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 61, 135–142. 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2007.12.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ho W.-Y., Choo Q.-C., Chew C.-H. (2017). Predominance of Three Closely Related Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus Clones Carrying a Unique ccrC-Positive SCC mec type III and the Emergence of spa t304 and t690 SCC mec type IV pvl+ MRSA Isolates in Kinta Valley, Malaysia. Microbial. Drug Resist. 23, 215–223. 10.1089/mdr.2015.0250 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmes A., McAllister G., McAdam P., Choi S. H., Girvan K., Robb A., et al. (2014). Genome-wide single nucleotide polymorphism-based assay for high-resolution epidemiological analysis of the methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus hospital clone EMRSA-15. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 20, O124–O131. 10.1111/1469-0691.12328 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holzknecht B. J., Hardardottir H., Haraldsson G., Westh H., Valsdottir F., Boye K., et al. (2010). Changing epidemiology of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in Iceland from 2000 to 2008: a challenge to current guidelines. J. Clin. Microbiol. 48, 4221–4227. 10.1128/JCM.01382-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hudson L. O., Murphy C. R., Spratt B. G., Enright M. C., Elkins K., Nguyen C., et al. (2013). Diversity of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) strains isolated from inpatients of 30 hospitals in Orange County, California. PLoS ONE 8:e62117. 10.1371/journal.pone.0062117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hudson L. O., Murphy C. R., Spratt B. G., Enright M. C., Terpstra L., Gombosev A., et al. (2012). Differences in methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus strains isolated from pediatric and adult patients from hospitals in a large county in California. J. Clin. Microbiol. 50, 573–579. 10.1128/JCM.05336-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ionescu R., Mediavilla J. R., Chen L., Grigorescu D. O., Idomir M., Kreiswirth B. N., et al. (2010). Molecular characterization and antibiotic susceptibility of Staphylococcus aureus from a multidisciplinary hospital in Romania. Microbial. Drug Resist. 16, 263–272. 10.1089/mdr.2010.0059 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jansen van Rensburg M., Eliya Madikane V., Whitelaw A., Chachage M., Haffejee S., Gay Elisha B. (2011). The dominant methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus clone from hospitals in Cape Town has an unusual genotype: ST612. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 17, 785–792. 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2010.03373.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Japoni-Nejad A., Rezazadeh M., Kazemian H., Fardmousavi N., van Belkum A., Ghaznavi-Rad E. (2013). Molecular characterization of the first community-acquired methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus strains from Central Iran. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 17, e949–e954. 10.1016/j.ijid.2013.03.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jappe U., Heuck D., Strommenger B., Wendt C., Werner G., Altmann D., et al. (2008). Staphylococcus aureus in dermatology outpatients with special emphasis on community-associated methicillin-resistant strains. J. Investig. Dermatol. 128, 2655–2664. 10.1038/jid.2008.133 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiménez J. N., Ocampo A. M., Vanegas J. M., Rodriguez E. A., Mediavilla J. R., Chen L., et al. (2013). A comparison of methicillin-resistant and methicillin-susceptible Staphylococcus aureus reveals no clinical and epidemiological but molecular differences. Int. J. Med. Microbiol. 303, 76–83. 10.1016/j.ijmm.2012.12.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jotić A., Božić D. D., Milovanović J., Pavlović B., Ješić S., Pelemiš M., et al. (2016). Biofilm formation on tympanostomy tubes depends on methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus genetic lineage. Eur. Arch. Oto Rhino Laryngol. 273, 615–620. 10.1007/s00405-015-3607-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jury F., Al-Mahrous M., Apostolou M., Sandiford S., Fox A., Ollier W., et al. (2006). Rapid cost-effective subtyping of meticillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus by denaturing HPLC. J. Med. Microbiol. 55, 1053–1060. 10.1099/jmm.0.46409-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kachrimanidou M., Tsorlini E., Katsifa E., Vlachou S., Kyriakidou S., Xanthopoulou K., et al. (2014). Prevalence and molecular epidemiology of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in a tertiary Greek hospital. Hippokratia 18:24. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karynski M., Sabat A. J., Empel J., Hryniewicz W. (2008). Molecular surveillance of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus by multiple-locus variable number tandem repeat fingerprinting (formerly multiple-locus variable number tandem repeat analysis) and spa typing in a hierarchic approach. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 62, 255–262. 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2008.06.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kechrid A., Pérez-Vázquez M., Smaoui H., Hariga D., Rodríguez-Baños M., Vindel A., et al. (2011). Molecular analysis of community-acquired methicillin-susceptible and resistant Staphylococcus aureus isolates recovered from bacteraemic and osteomyelitis infections in children from Tunisia. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 17, 1020–1026. 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2010.03367.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khandavilli S., Wilson P., Cookson B., Cepeda J., Bellingan G., Brown J. (2009). Utility of spa typing for investigating the local epidemiology of MRSA on a UK intensive care ward. J. Hosp. Infect. 71, 29–35. 10.1016/j.jhin.2008.09.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khemiri M., Alhusain A. A., Abbassi M. S., El Ghaieb H., Costa S. S., Belas A., et al. (2017). Clonal spread of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus-t6065-CC5-SCCmecV-agrII in a Libyan hospital. J. Glob. Antimicrobial. Resist. 10, 101–105. 10.1016/j.jgar.2017.04.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim T., Yi J., Hong K. H., Park J.-S., Kim E.-C. (2011). Distribution of virulence genes in spa types of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus isolated from patients in intensive care units. Korean J. Lab. Med. 31, 30–36. 10.3343/kjlm.2011.31.1.30 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ko K. S., Lee J.-Y., Suh J. Y., Oh W. S., Peck K. R., Lee N. Y., et al. (2005). Distribution of major genotypes among methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus clones in Asian countries. J. Clin. Microbiol. 43, 421–426. 10.1128/JCM.43.1.421-426.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Köck R., Brakensiek L., Mellmann A., Kipp F., Henderikx M., Harmsen D., et al. (2009). Cross-border comparison of the admission prevalence and clonal structure of meticillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. J. Hosp. Infect. 71, 320–326. 10.1016/j.jhin.2008.12.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kong H., Yu F., Zhang W., Li X., Wang H. (2017). Molecular epidemiology and antibiotic resistance profiles of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus strains in a tertiary hospital in China. Front. Microbiol. 8:838. 10.3389/fmicb.2017.00838 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]