Abstract

Purpose

To identify risk factors distinguishing inmates who attempt suicide from inmates who complete suicide.

Results

Compared to attempters, completers tended to be older, male, more educated, and married or separated/divorced; pre-trial, committed for a violent crime, incarcerated in jail, housed in an inpatient mental health unit or protective custody setting, living in a single cell, not on suicide precautions, not previously under close observation; and more likely to act during overnight hours and die by hanging/self-strangulation.

Conclusions

Targeted assessment of a broad range of risk factors is necessary to inform suicide prevention efforts in correctional facilities.

Keywords: inmate, suicide, risk factors, correctional facilities

Introduction

Suicide is a serious public health concern in correctional facilities (Noonan, Rohloff, & Ginder, 2015; World Health Organization [WHO], 2007). In the U.S., suicide is the number one cause of death in jails and the fifth leading cause of death in prisons (Noonan et al., 2015). From 2000–14, the annual mortality rate due to suicide ranged from 29 to 50 per 100,000 inmates in U.S. local jails and from 14 to 20 inmates in U.S. state prisons (Noonan, 2016a, 2016b). In contrast, in U.S. community populations, suicide is the 10th leading cause of death, where 13.3 of 100,000 people died by suicide in 2015 (Xu, Murphy, Kochanek, & Arias, 2016). Fortunately, not all who attempt suicide die as a result. Though rates for suicide attempts are difficult to obtain, one estimate suggests 734 of 100,000 jail inmates attempt suicide over a 12-month period (Goss et al., 2002)1. Within the community, the 12-month prevalence rate of suicide attempts ranges from 300 to 800 per 100,000 (Mościcki, 2001)2. Accurate identification for suicide risk is crucial to prevent suicide attempts and deaths in correctional facilities, particularly as historical declines in suicide rates within jails and prisons may now be reversing (Noonan, 2016a, 2016b).

The Interpersonal Theory of Suicide

Composed of three major constructs (i.e., perceived burdensome, thwarted belongingness, and acquired capability), the Interpersonal Theory of suicide explains factors that increase risk for suicidal behavior (Van Orden et al., 2010). This theory states that individuals are at higher risk for completing suicide when they believe they are a burden to others, become isolated, believe they are unwanted, and have a decreased fear of death and increased pain tolerance. Perceived burdensomeness and thwarted belongingness are likely to be prevalent in correctional facilities. Incarceration is a stressful experience for inmates’ loved ones, and recognition of this may lead to an individual to feel like a burden. Incarceration also makes the maintenance of social connections more challenging due to structural and financial barriers, which may lead to increased loneliness (i.e., social isolation) and fewer connections with reciprocally-caring others. Because of this, inmates may perceive themselves as unwanted. When combined with a decreased fear of death and elevated pain tolerance as captured by the acquired capability construct, individuals are at an increased risk for suicide.

Past Research Comparing Inmate Suicide Attempts to Completions

Substantial research has examined factors that put inmates at risk for attempting or completing suicide compared to non-suicidal controls (e.g., Fazel, Cartwright, Norman-Nott, & Hawton, 2008; Kerkhof & Bernasco, 1990). This information is crucial for distinguishing who is at greatest risk within the entire inmate population, but does not explain how inmates who attempt suicide are similar to or different from those who complete suicide. Such knowledge would inform assessment and delivery of proactive, appropriate interventions to prevent the most lethal of suicidal behavior. The present study seeks to fill this hole in the literature using a large, multi-jurisdictional, multi-system sample.

To our knowledge, only three empirical studies have compared prison inmates who attempted suicide to those who completed suicide, each modest in sample size. In a study of 54 suicide attempters and 37 completers in a U.S. state prison, Daniel and Fleming (2005) found no differences in demographic factors, type of crime committed, or sentence length. However, inmates who completed suicide were more likely to be housed in single cells or mental health housing than those who attempted suicide. Additionally, completers were more likely to die by hanging, whereas attempters were more likely to overdose.

In a sample of male U.S. federal inmates, Daigle (2004) examined differences in risk factors among attempters (n = 43), completers (n = 47), and non-suicidal inmates (n = 123). Similar to Daniel and Fleming (2005), Daigle (2004) found no differences in age between attempters and completers.

In a sample of male Canadian prison inmates, Serin, Motiuk, and Wichmann (2002) examined differences in risk factors among attempters (n = 48), completers (n = 48), and non-suicidal controls (n = 48). Unlike previous studies, Serin et al. (2002) found completers were older and were more likely to be in maximum security than attempters. Consistent with Daniel and Fleming (2005), Serin et al. found attempters were more likely to overdose or harm themselves by cutting, and completers were more likely to die by hanging or suffocation.

In contrast to the limited research comparing individuals who attempt with those who complete suicide in correctional facilities, many studies have conducted such comparisons in community samples using national (CDC) and global (WHO) data. Specifically, individuals who are female, adolescent or young adult, unmarried, unemployed, and less educated, are more likely to report suicidal ideation, plans to commit suicide, or attempt suicide. Compared to attempters, those who complete suicide in the community are more likely to be male, middle-aged or older adult (over 65 years), divorced or widowed, White, and to utilize more lethal methods for suicide (Godsmith, Pelllmar, Kleinman & Bunney, 2002; McIntosh & Drapeau, 2014; Nock et al., 2008).

Current Study

Preventing suicidal behavior is arguably more pressing in correctional facilities than in the community. Suicide rates are higher than in the community, and correctional authorities have direct responsibility for inmates’ welfare. Limited research tells us which inmates who engage in suicidal acts are most at-risk for dying. Little is known about such factors as type of correctional facility, type of crime committed, and time of suicide incident in distinguishing between inmates who attempt versus complete suicide.

The current study draws on a large multi-state, multi-jurisdiction sample to fill the gaps in the literature and examine differences between inmates who attempted suicide and those who completed suicide in U.S. jails and prisons. Differences in demographic, criminal justice, institutional, and incident-related factors are examined. This investigation is largely exploratory given the scant existing research. The goal is to identify factors placing inmates at a greater risk for dying by suicide in correctional facilities.

Method

Participants

Participants were 925 jail and state prison inmates who attempted or completed suicide between January 2007 and October 2015 at correctional facilities in eight states where mental health and/or medical services were provided by MHM Services, Inc. Permission to use the data was provided by the correctional agency and Institutional Review Board (IRB) approval was obtained, where required. Of the total sample, 79.5% (n = 735) attempted3 and 20.5% (n = 190) completed suicide. Participants were 82.7% male and on average, 34.01 years old (SD = 10.49 years, range = 15 to 75 years). The majority were White (63.4%) or Black (25.2%), had completed 9 to 12 years of education (80.3%), and were never married (70.5%).

Measures and Procedures

Behavioral health professionals at correctional facilities completed tracking sheets following attempted or completed suicides. Information included demographic, psychological, and institutional factors relevant to the event. Information relevant to the aims of the current study is presented here.

Demographic factors: age, sex, race/ethnicity, highest education completed, and marital status.

Criminal justice factors: pre- vs. post-trial status, type of crime that led to the current incarceration (i.e., violent vs. non-violent), length of time incarcerated prior to suicide-related incident4, and inmate security level.

Institutional factors: jail vs. prison, housing placement at time of suicide (e.g., restrictive housing, general population), type of cell, on suicide precautions at the time of the incident, ever under close observation, and time since most recent discharge from close observation.

Suicide-related incident factors: month, day of week, and time of day of suicide-related incident, and method used (i.e., cutting, overdose, hanging/self-strangulation).

Results

Plan of Analysis

Analyses compared attempters and completers. For individuals with multiple suicide-related incidents, data from the most recent incident was utilized. For categorical variables, chi-square tests were conducted. For continuous variables, independent samples t-tests were conducted, and for ordinal data, Mann-Whitney U tests were utilized.

Demographic Factors

Individuals who completed suicide (M = 38.32 years, SD = 12.73 years) were significantly older than those who attempted suicide (M = 32.88 years, SD = 9.51 years), t(241.77) = −5.44, p < .001. Those who completed suicide were more highly educated than those who had attempted suicide, U = 33618, p = .028. Males and individuals who were married or separated/divorced were more likely to complete vs. attempt suicide (Table 1). No race differences emerged.

Table 1.

| Demographic Factor | Attempter Observed (Expected) |

Completer Observed (Expected) |

Chi-Square Test |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | 24.27*** | ||

| Male | 584 (606.9) | 180 (157.1) | |

| Female | 150 (127.1) | 10 (32.9) | |

|

| |||

| Race | 1.46 | ||

| Black | 187 (180.7) | 42 (48.3) | |

| White | 449 (455.3) | 128 (121.7) | |

|

| |||

| Marital Status | 13.30** | ||

| Never Married | 387 (368.5) | 95 (113.5) | |

| Married | 63 (71.9) | 31 (22.1) | |

| Separated/Divorced | 73 (82.6) | 35 (25.4) | |

|

| |||

| Criminal Justice Factor | |||

|

| |||

| Pre-vs. Post-Trial | 8.08** | ||

| Pre-Trial | 63 (73.5) | 30 (19.5) | |

| Post-Trial | 613 (602.5) | 149 (159.5) | |

|

| |||

| Type of Crime | 13.37*** | ||

| Non-Violent | 380 (357.7) | 75 (97.3) | |

| Violent | 315 (337.3) | 114 (91.7) | |

|

| |||

| Inmate Security Level | 6.09* | ||

| Minimum | 70 (75.7) | 25 (19.3) | |

| Medium | 383 (368.9) | 80 (94.1) | |

| Maximum | 249 (257.4) | 74 (65.6) | |

|

| |||

| Institutional Factor | |||

|

| |||

| Jail vs. Prison | 18.42*** | ||

| Jail | 33 (45.9) | 25 (12.1) | |

| Prison | 685 (672.1) | 165 (177.9) | |

|

| |||

| Housing Placement | 12.00** | ||

| Segregation | 252 (242.7) | 50 (59.3) | |

| MHU/Inpatient Unit | 92 (102.1) | 35 (24.9) | |

| Protective Custody | 13 (16.9) | 8 (4.1) | |

| General Population | 200 (195.3) | 43 (47.7) | |

|

| |||

| Type of Cell | 22.62*** | ||

| Single | 373 (384.1) | 111 (99.9) | |

| Double | 187 (195.2) | 59 (50.8) | |

| Dormitory | 113 (93.6) | 5 (24.4) | |

|

| |||

| On Suicide Precautions | 118.23*** | ||

| No | 290 (356.8) | 159 (92.2) | |

| Yes | 445 (378.2) | 31 (97.8) | |

|

| |||

| Ever Under Close Observation | 18.17*** | ||

| No | 390 (415.6) | 135 (109.4) | |

| Yes | 320 (294.4) | 52 (77.6) | |

Note.

p < .001;

p < .01;

p < .05;

Ns = 840–1036

Criminal Justice Factors

Inmates who were pre-trial, committed for a violent crime, or classified as minimum or maximum security were more likely to complete than to attempt suicide (Table 1). Those who were post-trial, committed for a non-violent crime, or classified as medium security were more likely to attempt suicide.5 Length of time incarcerated prior to the incident was not significant.

Institutional Factors

Inmates who were incarcerated in jail, housed in an inpatient mental health unit or Protective Custody setting, or living in a single or double cell were more likely to complete suicide (Table 1). Those incarcerated in prison, housed in segregation or general population, or living in dormitory housing, were more likely to attempt suicide. Those who were not on suicide precautions and who have never been under close observation, were more likely to complete suicide. Those who were more recently discharged from close observation were more likely to complete suicide, compared to those who had been discharged from close observation more distally, U = 6541, p = .005.

Incident-Related Factors

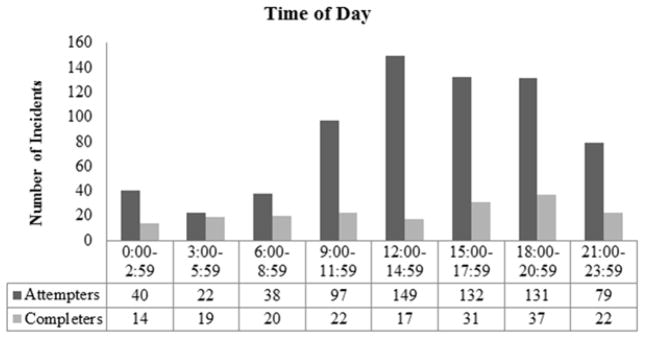

Individuals were more likely to complete suicide during overnight hours from 6pm to 9am (Table 2). Individuals were more likely to attempt suicide between 9am to 6pm, with an elevation in attempts between noon and 9 pm (Figure 1). Individuals who used hanging/self-strangulation were more likely to complete suicide, whereas those who cut themselves or overdosed were more likely to attempt suicide. Month and day of the week were not significant.

Table 2.

| Incident-Related Factor | Attempter Observed (Expected) |

Completer Observed (Expected) |

Chi-Square Test |

|---|---|---|---|

| Month | 14.59 | ||

| January | 58 (58.7) | 16 (15.3) | |

| February | 58 (57.1) | 14 (14.9) | |

| March | 58 (58.7) | 16 (15.3) | |

| April | 66 (69.1) | 21 (17.9) | |

| May | 56 (57.1) | 16 (14.9) | |

| June | 76 (76.2) | 20 (19.8) | |

| July | 61 (69.8) | 27 (18.2) | |

| August | 81 (73.0) | 11 (19.0) | |

| September | 86 (81.8) | 17 (21.2) | |

| October | 43 (46.0) | 15 (12.0) | |

| November | 47 (42.9) | 7 (11.1) | |

| December | 41 (40.5) | 10 (10.5) | |

|

| |||

| Day of Week | 3.88 | ||

| Sunday | 89 (96.0) | 32 (25.0) | |

| Monday | 112 (114.2) | 32 (29.8) | |

| Tuesday | 132 (127.7) | 29 (33.3) | |

| Wednesday | 101 (98.4) | 23 (25.6) | |

| Thursday | 117 (116.6) | 30 (30.4) | |

| Friday | 93 (91.2) | 22 (23.8) | |

| Saturday | 85 (84.9) | 22 (22.1) | |

|

| |||

| Time of Day | 35.68*** | ||

| 0:00–2:59 | 40 (42.7) | 14 (11.3) | |

| 3:00–5:59 | 22 (32.4) | 19 (8.6) | |

| 6:00–8:59 | 38 (45.9) | 20 (12.1) | |

| 9:00–11:59 | 97 (94.1) | 22 (24.9) | |

| 12:00–14:59 | 149 (131.3) | 17 (34.7) | |

| 15:00–17:59 | 132 (128.9) | 31 (34.1) | |

| 18:00–20:59 | 131 (132.9) | 37 (35.1) | |

| 21:00–23:59 | 79 (79.9) | 22 (21.1) | |

|

| |||

| Method | 193.18*** | ||

| Cutting | 253 (201.1) | 5 (56.9) | |

| Overdose | 160 (128.6) | 5 (36.4) | |

| Hanging/Self-Strangulation | 238 (321.2) | 174 (90.8) | |

Note.

p < .001;

p < .01;

p < .05;

Ns = 963–1036

Figure 1.

Suicide attempts and completions by time of day.

Discussion

The current study substantially extends the literature on differences between inmates who attempted vs. completed suicide during incarceration by considering a broader range of demographic, criminal justice, institutional, and incident-related characteristics, and drawing on a much larger, multi-state sample of jail and prison inmates. Significant differences were found across domains, suggesting targeted assessment of a complex array of both static and dynamic risk factors is necessary to inform suicide prevention efforts in correctional facilities.

Demographic Factors

As in prior studies of correctional (Serin et al., 2002) and community populations (Godsmith et al., 2002; Nock et al., 2008), our results demonstrate that completers are more likely than attempters to be male, older, and divorced. However, neither Daniel and Fleming (2005) nor Daigle (2004) found age differences between inmate attempters and completers; Daniel and Fleming (2005) also found no differences in race or sex. These inconsistencies may be due to lack of power to detect effects in those studies. Furthermore, in the present study, completers tended to be more educated than attempters. It is possible that more educated inmates were more likely to perceive themselves as a burden to others and/or as less able to belong, as those who are more educated may have held more prestigious jobs, which they may not be able to return to post-release due to accrual of a criminal record.

Criminal Justice Factors

Attempters and completers differed on all three criminal justice characteristics. Consistent with higher national suicide rates in jails compared to prisons, pre-trial inmates were more likely to complete suicide than post-trial inmates. Time prior to trial may be particularly stressful given the relative recency and potential shock of arrest, perception of being suddenly unwanted and a burden, uncertainty about the future, lack of time to acclimate to the correctional environment, limited meaningful daytime activities, and pervasive changes in the inmate’s life situation. All of these factors may lead pre-trial inmates to take more lethal steps to end one’s life.

Inmates convicted of violent crimes were more likely to complete suicide. Inmates convicted of violent crimes may be at greater risk for completing suicide for at least two reasons. First, there some evidence indicating that past violence may be a risk factor for suicide among inmates (e.g., Hayes, 2000). Individuals with history of violence may struggle more with impulsivity, anger, and hostility, as well as interpersonal alienation and thwarted belongingness, and may be more willing to complete suicide. Second, it may be these individuals face longer prison sentences, which could lead to increased isolation and perceived burdensomeness compared to non-violent inmates. Our findings are inconsistent with Daniel and Fleming’s (2005) findings, but their comparatively small sample size may have limited power to detect this effect.

Inmates housed in minimum and maximum security were more likely to complete suicide than those in medium security. This may be due to differences in monitoring; minimum security inmates may be surveilled less than inmates on higher security levels, potentially leaving unsupervised time when suicide-related behaviors can occur. Minimum security inmates may also be closer to release; This creates significant stress and could increase perceived burdensomeness and heighten a sense of alienation/thwarted belongingness. Maximum security inmates have more surveillance, but may have histories of increased impulsivity and violence, increased environmental stress, and the potential for mental health problems. These factors may lead to greater suicidality compared to inmates on other security levels. This finding adds to Serin et al. (2002), who found completers were more likely to be maximum security than were attempters.

Institutional Factors

Attempters and completers differed on all five institutional characteristics, including institutional factors not considered in prior research. Jail inmates were more likely to complete than attempt suicide compared to prison inmates. As noted, jail tends to have different associated stressors (e.g., shock of initial incarceration, sudden alienation from social supports, anxiety while awaiting sentencing) and lengths of incarceration compared to prison. Existing studies examining differences in risk factors between attempters and completers assessed prison inmates, not jail inmates. The results of the current study suggest the need to examine unique risk factors for suicide attempts and completions in both jail and prison inmates.

Those not on suicide precautions, recently discharged from close observation, or never under close observation were more likely to die by suicide than those on suicide precautions or under close observation. This may be due to differences in monitoring. Inmates not on suicide precautions may go unnoticed by security and mental health staff, allowing them to complete suicide. Those never under close observation may not have come to the attention of mental health staff, precluding timely intervention. In contrast, regular, frequent follow-ups by mental health staff provided to inmates on and following close observation may provide support and monitoring necessary to prevent death by suicide. Results support the conclusion that suicide precautions with frequent follow-ups by mental health staff constitute an effective suicide prevention strategy.

Incident-Related Factors

Attempters and completers differed on two of the four incident-related factors. Completers were more likely to act during overnight hours and to use more lethal methods. Less direct supervision during overnight hours due to lack of movement for programs, meals, etc., likely contributes to the higher completion rates compared to daytime hours. Regarding method, results are consistent with prior research (Daniel & Fleming, 2005; Hayes, 2000; Serin et al., 2002). Completers were more likely to die by hanging/self-asphyxiation whereas attempters were more likely to attempt via less lethal methods (e.g., cutting).

Results of the current study are also consistent with prior findings that completers were housed in an inpatient mental health unit or protective custody (Daniel & Fleming, 2005). Those on the mental health/inpatient unit may already be at greater risk for completing suicide due to serious mental health issues that led to placement on the unit (Brown, Beck, Steer, & Grisham, 2000). Similarly, protective custody may be associated with unique risks for suicide, given that protective custody inmates may have fears of being harmed and/or experience ongoing levels of interpersonal conflict and alienation. These individuals are typically housed adjacent inmates under disciplinary segregation in units designed to enhance security and minimize social contact; living under these conditions may contribute to feelings of isolation and increase in distress, which can ultimately result in suicide (Bonner, 2010).

Inmates living in single cells were more likely to complete suicide, as found in prior work (Daniel & Fleming, 2005; Hayes, 2010). Inmates in single cells lack informal monitoring provided by cell-mates, allowing for more opportunities to engage in lethal methods. Inmates in double cells were also at greater risk to complete suicide compared to those in dorms, although less at-risk than those in single cells. Dormitory housing appears to be a protective factor against dying by suicide, likely due to increased social engagement, belongingness, and monitoring and less social isolation.

Limitations and Future Directions

Due to the nature of archival data, we do not have information for all suicide-related behaviors that occurred at every facility or correctional system in the sample. Although multistate and much larger than extant studies, the current study does not represent prevalence data that can be found through comprehensive national surveys. Furthermore, the data is drawn from facilities at which MHM Services, Inc. provides services. As such, the results may not be representative of all U.S. correctional facilities.

As a retrospective archival study, we did not include non-suicidal controls as a comparison group. Inclusion of this group would allow examination of factors putting individuals at-risk for suicidal behavior and to distinguish risk factors for attempts vs. completions. Motivations for the suicide attempts in the current study are unknown, and it is likely some of the attempted suicides are non-suicidal self-injury without intent to die. However, these were serious incidents requiring medical attention.

Conclusions

Is it possible to determine which individuals who will die by suicide vs. attempting and surviving? Although accurate prediction is challenging, effective suicide prevention can be achieved by proactively addressing the risk factors identified in this study. Recommendations based on the current study include: 1) increased monitoring for inmates with identifiable risk factors; 2) increased surveillance after hours; and 3) housing individuals at-risk for suicide with others. While acute separation and monitoring are important, isolation is a risk factor for suicide.

Acknowledgments

Funding: This work was supported by the National Institute on Drug Abuse [grant number 1F31DA039620]

Footnotes

Goss et al. (2002) estimated 2,200 of 100,000 jail inmates attempted suicide over a 33-month period. To make the comparable this to annual rates, 2,200 was divided by three to obtain an annualized rate of 734 per 100,000 inmates.

No statistic was found for suicide attempts in prison. However, Appelbaum et al., (2011) reported that in 2008, 8,680 of 1.22 million prison inmates engaged in self-injurious behavior (p. 286), equivalent to a 12-month rate of 711 per 100,000.

We defined suicide attempt as any self-harm incident requiring medical intervention that could not be managed within the correctional facility; this criterion was used to capture more severe incidents that required off-site medical care in an emergency department or hospital. However, as in Goss et al., 2002, we did not differentiate “real” attempts with suicidal intent from behavior that may not have involved suicidal intent. The two categories of inmate behavior often have similar characteristics (Lester, Beck, & Mitchell, 1979), and the motivation behind an act (e.g., desire to die) does not distinguish insignificant medical from life-threatening events (Dear, Thomson, & Hills, 2000; Haycock, 1989). It is likely that some incidents we are calling “suicide attempts” did not involve lethal intent, just as it is possible that some completed suicides may have involved misjudged self-harm and unintended death.

This variable was log transformed because it was positively skewed (original skew = 2.46, SE of skew = 0.12).

It is likely that pre- vs. post-trial is essentially analogous to jail vs. prison. In our sample, 81% of those incarcerated in jail were pre-trial and 95% of those incarcerated in prison were post-trial. Due to the small sample sizes within some of the cells (e.g., only one post-trial jail inmate completed suicide; only seven pre-trial prison inmates completed suicide), chi-square analyses could not be conducted separately based on facility type.

References

- Alexander M. The new Jim Crow: Mass incarceration in the age of colorblindness. New York: New Press; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Appelbaum KL, Savageau JA, Trestman RL, Metzner JL, Baillargeon J. A national survey of self-injurious behavior in American prisons. Psychiatric Services. 2011;62:285–290. doi: 10.1176/ps.62.3.pss6203_0285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonner RL. Correctional suicide prevention in the year 2000 and beyond. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior. 2000;30:370–376. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown GK, Beck AT, Steer RA, Grisham JR. Risk factors for suicide in psychiatric outpatients: a 20-year prospective study. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2000;68:371. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bureau of Justice Statistics. Reentry trends in the U.S. 2002 Retrieved October 20, 2016, from http://www.bjs.gov/content/reentry/reentry.cfm.

- Carson EA. Prisoners in 2014. Bureau of Justice Statistics; Washington, D.C: U.S. Department of Justice; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Daigle M. MMPI inmate profiles: suicide completers, suicide attempters, and non-suicidal controls. Behavioral Sciences and the Law. 2004;22:833–842. doi: 10.1002/bsl.618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daniel AE, Fleming J. Serious suicide attempts in a state correctional system and strategies to prevent suicide. The Journal of Psychiatry & Law. 2005;33:227–247. [Google Scholar]

- Dear GE, Thomson DM, Hills AM. Self-harm in prison: Manipulators can also be suicide attempters. Criminal Justice and Behavior. 2000;27:160–175. [Google Scholar]

- Drapalski AL, Youman K, Stuewig J, Tangney J. Gender differences in jail inmates’ symptoms of mental illness, treatment history and treatment seeking. Criminal Behaviour and Mental Health. 2009;19:193–206. doi: 10.1002/cbm.733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fazel S, Cartwright J, Norman-Nott A, Hawton K. Suicide in prisoners: A systematic review of risk factors. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 2008;69:1721–1731. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fruehwald S, Eher R, Frottier P. What was the relevance of previous suicidal behaviour in prison suicides? Canadian Journal of Psychiatry. Revue Canadienne de Psychiatrie. 2001;46:763–763. doi: 10.1177/070674370104600818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldsmith SK, Pellmar TC, Kleinman AM, Bunney WE. Reducing suicide: A national imperative. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2002. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goss JR, Peterson K, Smith LW, Kalb K, Brodey BB. Characteristics of suicide attempts in a large urban jail system with an established suicide prevention program. Psychiatric Services. 2002;55:574–579. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.53.5.574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haycock J. Manipulation and suicide attempts in jails and prisons. Psychiatric Quarterly. 1989;60:85–98. doi: 10.1007/BF01064365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes LM. National study of jail suicide: 20 years later. National Institute of Corrections: National Center on Institutions and Alternatives; 2010. Retrieved October 23, 2016 from http://static.nicic.gov/Library/024308.pdf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He XY, Felthous AR, Holzer CE, Nathan P, Veasey S. Factors in prison suicide: One year study in Texas. Journal of Forensic Science. 2001;46:896–901. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joiner TE, Conwell Y, Fitzpatrick KK, Witte TK, Schmidt NB, Berlim MT, … Rudd MD. Four studies on how past and current suicidality relate even when “everything but the kitchen sink” is covaried. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2005;114:291–303. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.114.2.291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerkhof AJ, Bernasco W. Suicidal behavior in jails and prisons in the Netherlands: Incidence, characteristics, and prevention. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior. 1990;20:123–137. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lester D, Beck AT, Mitchell B. Extrapolation from attempted suicides to completed suicides: A test. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1979;88:78–80. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.88.1.78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McIntosh JL, Drapeau CW (for the American Association of Suicidology) U.S.A. suicide 2012: Official final data. Washington, DC: American Association of Suicidology; 2014. dated June 19, 2014, downloaded from http://www.suicidology.org. [Google Scholar]

- Mościcki EK. Epidemiology of completed and attempted suicide: Toward a framework for prevention. Clinical Neuroscience Research. 2001;1:310–323. [Google Scholar]

- National Center for Injury Prevention and Control. Suicide: Facts at a glance. 2015 Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/ViolencePrevention/pdf/Suicide-DataSheet-a.pdf.

- Nock MK, Borges G, Bromet EJ, Cha CB, Kessler RC, Lee S. Suicide and suicidal behavior. Epidemiologic Reviews. 2008;30:133–154. doi: 10.1093/epirev/mxn002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noonan M. Mortality in local jails, 2000–2014, Statistical tables. Bureau of Justice Statistics; Washington, D.C: U.S. Department of Justice; 2016a. [Google Scholar]

- Noonan M. Mortality in state prisons, 2000–2014, Statistical tables. Bureau of Justice Statistics; Washington, D.C: U.S. Department of Justice; 2016a. [Google Scholar]

- Serin RC, Motiuk L, Wichmann C. An examination of suicide attempts among inmates. Forum on Corrections Research. 2002;14(2):40–42. Correctional Service of Canada. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Census Bureau. Population Estimates. 2013 Jul 1; Retrieved May 19, 2016, from http://www.census.gov/popest/data/historical/2010s/vintage_2013/national.html.

- World Health Organization. Preventing suicide in jails and prisons. 2007 Retrieved from: http://www.who.int/mental_health/prevention/suicide/resource_jails_prisons.pdf.

- World Health Organization. Preventing suicide: A global imperative. 2014 Retrieved from: http://www.who.int/mental_health/suicide-prevention/world_report_2014/en/

- Xu J, Murphy SL, Kochanek KD, Arias E. Mortality in the United States, 2015. NCHS data brief. 2016:1–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]