Abstract

Dry eye disease (DED) affects millions of individuals in the United States and worldwide, and the incidence is increasing with an aging population. There is widespread agreement that the measurement of total tear osmolarity is the most reliable test, but this procedure provides only the total ionic strength and does not provide the concentration of each ionic species in tears. Here, we describe an approach to determine the individual ion concentrations in tears using modern silicone hydrogel (SiHG) contact lenses. We made pH (or H3O+, hydronium cation, /OH−, hydroxyl ion) and chloride ion (two of the important electrolytes in tear fluid) sensitive SiHG contact lenses. We attached hydrophobic C18 chains to water-soluble fluorescent probes for pH and chloride. The resulting hydrophobic ion sensitive fluorophores (H-ISF) bind strongly to SiHG lenses and could not be washed out with aqueous solutions. Both H-ISFs provide measurements which are independent of total intensity by use of wavelength-ratiometric measurements for pH or lifetime-based sensing for chloride. Our approach can be extended to fabricate a contact lens which provides measurements of the six dominant ionic species in tears. This capability will be valuable for research into the biochemical processes causing DED, which may improve the ability to diagnose the various types of DED.

Keywords: Dry eye disease, fluorescence sensors, contact lens, electrolytes, chloride ion, hydronium ion, silicone hydrogels, hydrogels

Graphical Abstract

Introduction

Dry eye disease (DED) is a multifactorial disease affecting the tear composition and corneal surfaces of the eye. DED affects a large fraction of the population, with estimates up to 59 million individuals in the United States [1–4]. The symptoms of DED include eye discomfort, burning sensations, and blurred vision. In advanced stages, DED can be debilitating, resulting in damage of the corneal surface, eye infections, impaired vision, corneal ulceration, and even blindness [5]. DED is not a single disease and can be due to several different factors [6–7]. For example, when the lipid layers of the tear film are deficient, an excessive rate of evaporation occurs, leading to evaporative dry eye (EDE) [8–9]. Sjögren syndrome is the result of inadequate tear production [10]. Systemic causes such as vitamin A deficiency, local conditions, infections or contact lens wear [11–12] can also contribute towards DED.

Given the multifactorial nature of DED, appropriate treatment depends on identifying the underlying specific cause of the condition. However, it can be difficult for physicians to identify the form of DED in a given patient, and the available tests are difficult to standardize. Most forms of DED are highly correlated with an electrolyte imbalance in tears. Although, increase in total osmolarity is regarded as the most accurate and objective biomarker for DED [13–15], and superior to almost all the other tests for DED (Table 1), there is a recognized need for other biomarkers for DED [16–17]. The procedures currently used to detect and diagnose DED can be unreliable and often do not reveal the form of DED which is occurring in the patient. As an example, the Schrimer test depend on capillary migration of tears into a filter paper, and the migration distance is used to determine the absence or presence of DED [18–19]. A short migration distance may indicate the cause is aqueous-deficient DED (ADDED), but inserting the paper strips can influence the results. These tests do not indicate the individual concentrations of any of the ionic species, but individual ion concentrations can help to identify the form of DED. For example, inflammation of the cornea is known to be associated with neutrophils [20–21] and activated neutrophils release protons [22–24]. A decrease in tear pH may reveal a corneal infection before it is visible to the clinician. Potassium appears to be an important component in tears because its concentration is 7-fold higher than in blood (Table 2). Potassium is needed to maintain corneal epithelial [25] and gene expression shows K+ transporters on the lacrimal gland duct membranes [26]. A two-fold increase in Na+ reported as due to aquaporin-5 deficiency in mice [27]. Subsequently, the presently available tests measure total tear osmolarity [28], and there are no practical tests which provide the concentrations of each electrolyte, which for tears include pH (H3O+/OH−) Na+, K+, Ca2+, Mg2+ and chloride ion (Table 2). We describe an approach of using ion-sensitive contact lenses which can be used to determine the concentrations of all these electrolytes in tears (Figure 1).

Table 1.

Sensitivity and Specificity of Objective Clinical Signs of Dry Eye Disease [15]

| Test | Cutoff | Sensitivity | Specificity |

|---|---|---|---|

| Osmolarity | > 311 mOsm | 72.8% | 92.0% |

| TBUT | < 10 sec | 84.4% | 45.3% |

| Schrimer | < 18 mm | 79.5% | 50.7% |

| Corneal stain | > Grade 1 | 54.0% | 89.3% |

| Conjunctival stain | > Grade 2 | 60.3% | 90.7% |

| Meibormian grade | > Grade 5 | 61.2% | 78.7% |

Table 2.

Electrolyte Concentrations in Blood Serum and Tears

| Blood | Tears | |

|---|---|---|

| pH | 7.35 – 7.46 | 6.5 – 7.6 |

| (H3O+) | (35 – 45 nM) | 25 – 316 nM) |

| Na+ | 135 – 148 mM | 132 mM |

| K+ | 3.5 – 5.3 mM | 24 mM |

| Ca2+ | 4.5 – 5.5 mM | 0.8 mM |

| Mg2+ | 0.7 – 1.0 mM | 0.6 mM |

| Cl− | 95 – 110 mM | 118 – 138 mM |

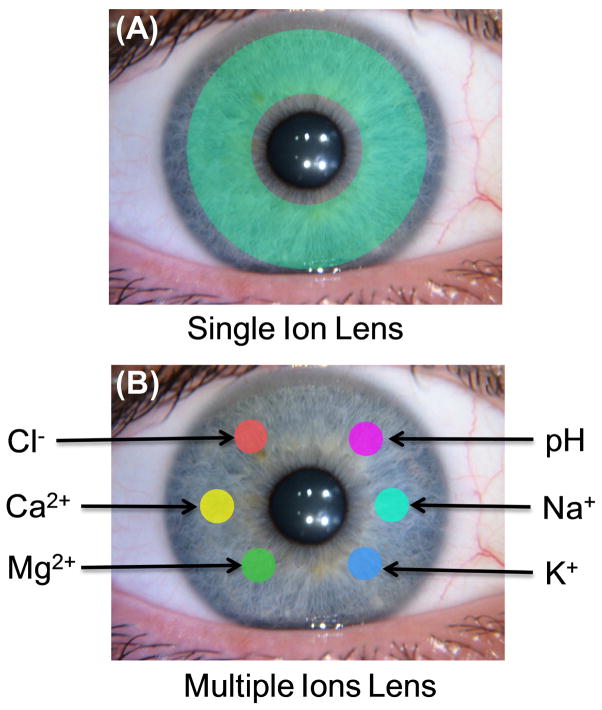

Figure 1.

(A). Schematic of contact lens for measurement of a specific single ion. The schematic green shading indicates the location of the ion-sensitive fluorophore. (B) Schematic of a contact lens for complete electrolytes analysis in tears. Each color spot represents a different ion-specific fluorophores.

Over the past 20 years there has been extensive development of water-soluble fluorophores for the electrolytes listed in Table 2, and many other ionic species. These probes have been described in detail in many books and reviews [29–32] and are commercially available. Multiple probes are available for each ionic species. For instance, at least six probes for chloride have been well characterized and well over ten for Ca2+ and Mg2+ [33], and are usually available over a range of wavelengths. Therefore, sensing fluorophores are available for all the ionic species in tears and many other analytes. Additionally, most of these probes were designed to be highly charged and/or polar for high solubility in water and retention within cells. We anticipate that these ion-sensitive fluorophore regions will remain in the aqueous channels of the SiHG lenses after modification with a hydrophobic side chain at a location that does not interfere with the sensing location on the fluorophore (vide infra).

For clinical use it must be possible to obtain information about the electrolyte concentrations in a way which is independent of total fluorescence intensity, and to be reasonably resistant to interference by ambient light. This is possible because many ion-sensitive probes display emission spectral shifts upon binding its target species. A spectral shift allows wavelength-ratiometric measurements which can be independent of total intensity. Other ion-sensitive fluorophores display changes in lifetime upon analyte binding. In these cases lifetime-based sensing in the time-domain (TD) or frequency-domain (FD) provides the ion concentrations independent of total intensity. If an ion-sensitive fluorophore displays a change in intensity, but does not display a spectral shift or a change in lifetime, a reference fluorophore can be used to provide a wavelength-ratiometric signal. Some of the most widely used probes require UV excitation. Ten years ago, simple UV light sources with low power requirements were essentially unknown. At present, many solid state LEDs and laser diodes are available for most wavelengths above 260 nm. Wavelengths near 350 nm will not be seen by the patient, this wavelength is not strongly phototoxic and the low intensity excitation will be absorbed by the cornea before reaching the retina [34–35]. Wavelengths below 400 nm are blocked by most contact lenses [36]. Subsequently we modify and use existing ion sensitive fluorophores in a contact lens for electrolyte estimation for DED diagnosis.

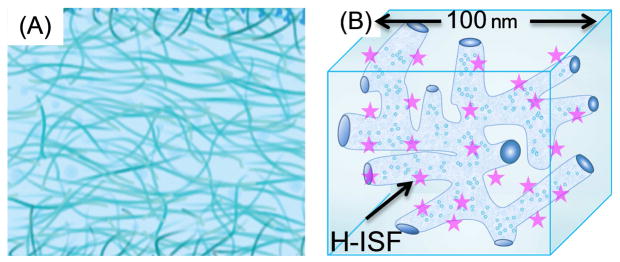

Modern silicone-hydrogel (SiHG) contact lenses provide an ideal binding and supporting structure for hydrophobic ion-sensitive fluorophores (H-ISF), which consist of an ion-sensitive fluorophore attached to a hydrophobic side chain. The use of H-ISFs was not possible using the previous generation of non-silicone hydrogel (HG) contact lenses. Figure 2 compares the internal morphology of a HG with a SiHG lens. HG lens are typically made of cross linked polymers such as polyhydroxyethyl methacrylate (HEMA). The interior regions of HG lenses are spatially uniform consisting of highly hydrated and intertwined polymer strands. In contrast, the interior regions of SiHG lenses are spatially heterogeneous, with some regions nearly 100% water and other regions nearly 100% silicone [37–38]. The silicone-rich regions are thought to be the major routes for oxygen transport, and the water-rich regions allow transport of electrolytes and other small molecules present in tear fluid [39–40]. Rapid transport of tear fluid occurs because the polar and non-polar regions of the SiHGs consist of interpenetrating polymer networks (IPN) which provide a continuous path of each region throughout the SiHG and across the thickness of the contact lens [41–44]. Because of their rapid transport of oxygen and tear fluid the SiHG lenses are now approved for long-time use and overnight wear [45–48]. The presence of polar and non-polar regions of the lenses suggests the presence of interfaces which provide an opportunity to localize H-ISFs at the interface (Figure 2). A hydrophobic side chain can prevent probe washout while the ion-sensitive moiety remains in the water channels with continuous exposure to tear fluid. With this rationale, we decided to adopt the concept of using H-ISFs in SiHGs offers the potential to measure all the dominant ionic species in tears.

Figure 2.

(A), Schematic cross section of non-silicone hydrogel (HG) contact lens with homogeneous interior structure. (B), Schematic of a small region of a SiHG showing the hydrophylic and hydrophobic interpenetrating polymer networks. The dimension is an approximation. The amphipathic H-ISFs are localized at the silicone-water interface throughout the contact lens by hydrophobic interactions.

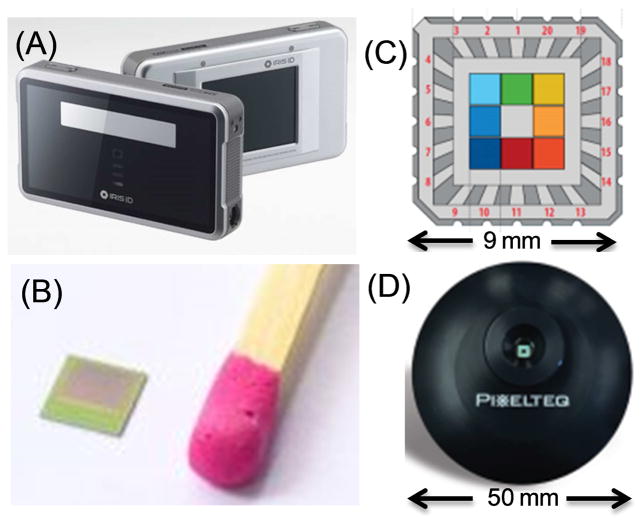

For clinical use the measurements must be made remotely without direct contact with the eye, which is possible with fluorescence detection. Such measurements would be clinically convenient using a hand-held device. The electronic technology is already available for such devices. Complementary metal-oxide-semiconductors (CMOS) array detectors are rapidly replacing the more expensive charged-coupled devices (CCDs). CMOS detectors are less expensive than CCDs. CMOS detectors are widely used with cameras and cell phones, and require 100-fold less power than CCDs [49–51]. CMOS detectors have high sensitivity and frame rates [52]. They have been used for live cell imaging and single molecule detection [53–54] and are capable of measuring nanosecond (ns) decay times and for fluorescence lifetime imaging microscopy (FLIM) [55–57] (Figure 3B). Compact multispectral sensors with large pixels for high sensitive (Figures 3C and D) have recently become available [58]. During an eye examination it will not be possible to eliminate eye movements. The problem of iris tracking has also been solved by devices for identification of individuals by imaging the iris, as shown by the cell-phone size device in Figure 3A. The software and hardware to image a moving iris is already available.

Figure 3.

(A), Iris identification security device. From Iris ID Inc. (B), 3D time-of-flight CMOS imaging detector for Laveno Tango cell phone announced in June 2016. (C), Pixel Sensor from Pixelteq.com providing eight band pass filters from 425 to 700 nm. (D), Pixel sensor in a functional housing.

In the present report we used polarity-sensitive fluorophores to show that non-polar and/or amphipathic molecules can bind to non-polar regions of the SiHG lenses. We then synthesized hydrophobic ion-sensitive fluorophores (H-ISFs) for pH and chloride, and demonstrated that they retain their sensing properties when bound to SiHG lenses. Our approach does not depend on the structure of the sensing fluorophore, and provides a pathway to making H-ISF for the Na+, K+, Ca2+ and Mg2+. Such a lens with multiple ion sensitive regions could be used to determine concentrations of the major electrolytes in tears (Figure 1B). The fluorescent signals from such a lens could be measured under equilibrium conditions, without contact with the eye which is known to alter the chemical composition of tears.

Materials and Methods

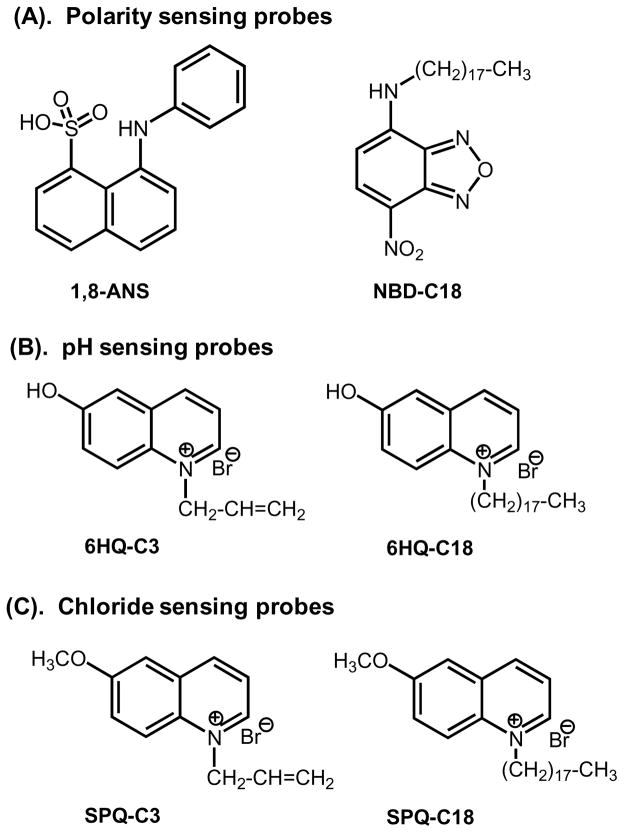

Polarity probes and H-ISFs

The probes used in this report are shown in Figure 4. 1-Anilinonaphthalene-8-sulfonic acid (1,8-ANS, ANS) and a 4-(1-octylamine)-7-nitrobenzoxadiazole (NBD-C18) were used as polarity sensitive probes. ANS is obtained from Sigma-Aldrich and used as received. NBD-C18 was prepared using a previously described procedure by us [59]. The SiHG and HG contact lenses, Comfilcon A (SiHG, Biofinity), Stenfilcon A (SiHG, Aspire) and Nelfilcon A (HG, Dailies), were obtained from commercial sources. The hydrophobic pH probe (6HQ-C18) was obtained by the quarternization reaction between equimolar amounts of 6-hydroxyquinoline (6-HQ) and 1-bromooctadecane in acetonitrile at room temperature. As a control we also prepared a water-soluble pH probe (6HQ-C3) with a short, C3 alkyl chain [60–61]. 6-methoxyquinolinium-containing (SPQ) probes were used for Cl ion sensing. The water soluble version SPQ-C3 was synthesized as described in references 60–61. The H-ISF for chloride ion called SPQ-C18 was made by attachment of a C18 alkyl chain using the same procedure. The H-ISFs were labeled by socking the contact lenses in methanolic probe solutions for 1hr followed by which were washed with water and buffer solutions for several times to eliminate the unbound probe from the contact lens. The dye doped lenses were stored in water until they were used for the measurements.

Figure 4.

Molecular structures of probes used for the present study.

Fluorescence Measurements

Emission spectra and time-resolved intensity decays of the dye doped lenses fixed to a specially designed contact lens mount were measured using a FluoTime 300 from PicoQuant and pulsed laser diodes for excitation. Time-resolved decays were recorded at emission maxima of the probes. Fluorescence lifetime imaging microscopy (FLIM) images were obtained using an Alba laser scanning confocal microscope from ISS, Inc.

Fluorescence Lifetime Analysis

Fluorescence intensity decays I(t) are typically analyzed with the multi-exponential model

| (1) |

where τi are the individual decay times and αi are the amplitudes of each component at τ = 0, and Σαi = 1.0 [62–63]. The values of αi and τi are determined using non-linear least-squares (NLLS) analysis. The fractional contribution of each component to the total steady-state emission is proportional to the product of αiτi. The multi-exponential model makes the implicit assumption that fluorophores in the sample exist in discrete populations with specific decay times. In these initial studies of fluorophores in contact lenses, there is no reason to assume unique populations. Hence the time-resolved decays were also analyzed using the lifetime distribution model [64–65] which allows continuous changes in the α and τ values. For this model the intensity decay is represented by

| (2) |

where ∫α(τ) dτ = 1.0. To decrease the number of variables in the NLLS analysis we constrained the α(τ) distribution to be a sum of Gaussian distribution [65]. The results of this analysis are presented as the fractional contribution to the total intensity, that is the product of the amplitude α(τi) multiplied by the lifetime τ. This mode of presentation provides results in an intuitive description of the overall intensity decays.

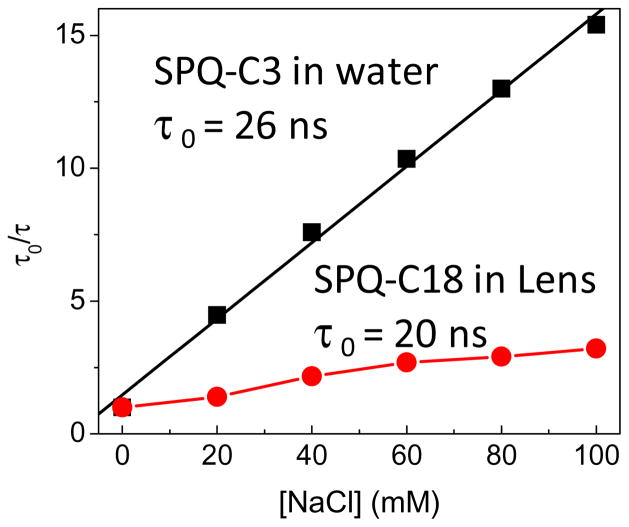

Collisional quenching of the chloride-sensitive probe was analyzed using the Stern-Volmer equation. In these plots the extent of collisional quenching is shown on the y-axis as the ratio of the lifetime in the absence (τ0) and in the presence (τ) of chloride. The slope K is the Stern-Volmer quenching constant, where K is the reciprocal concentration (M−1) for 50% of quenching,

| (3) |

The constant K is the product of the unquenched lifetime (τ0) and the rate of collisional quenching constant kq, which is also called the bimolecular quenching constant [33].

Results and Discussion

Selection of Contact Lenses

Soft contact lenses are made using a wide variety of highly specific polymer formulations. Table 3 lists some of the polymer names, commercial names, Dk values and water content. Oxygen transport is important because the cornea receives most of its needed oxygen from the air. The oxygen permeability of contact lens are described by the standardized Dk values described elsewhere [66–68]. Soft hydrogel (HG) contact lenses are typically made from HEMA and similar monomers. The Dk values of HG lenses can be increased by decreasing the polymer content and increasing the water content. To obtain oxygen permeabilities comparable to water (Dk = 35), it is necessary to use lenses with high water content, but the lenses becomes too fragile for practical use, which typically involved daily removal and washing of the lenses. We selected Nelfilcon A (HG, Dalies) as representative of presently used HG lenses and as a control for comparison with the SiHG lenses.

Table 3.

Selected Silicone Hydrogels

| Polymer | Trade Name | Manufacture | Water (%) | Dk |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lotrafilcon A (SiHG) | Night and Day | CIBA vision | 24 | 140 |

| Galyfyilcon A (SiHG) | Acuvue Advance | Johnson & Johnson | 47 | 60 |

| Comfilcon A (SiHG) | Biofinity | Cooper Vision | 48 | 128 |

| Stenfilcon A (SiHG) | Aspire, 1 day | Cooper Vision | 54 | 80 |

| Latrofilcon B (SiHG) | Air OptixAqua | Ciba Vision/Alcon | 33 | 138 |

| Nelfilcon A (HG) | Aqua Release | Ciba Vision | 69 | 26 |

| Nelfilcon A (HG) | Dailies | Ciba Vision | 69 | 26 |

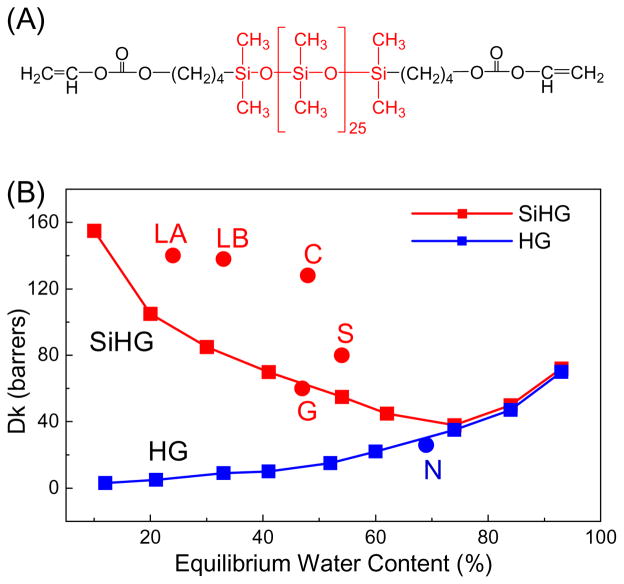

The problem of oxygen transport to the cornea was solved by using monomers which contain silicone regions (Figure 5A) which improves oxygen solubility and transport. The Dk values of SiHG lenses can exceed that of pure water by several-fold (Figure 5B). At present about 90% of new contact lens prescriptions are for SiHG lenses [69]. The currently used S-HG lenses can have different chemical compositions. The exact chemical composition and/or polymerization methods are trade secrets, but it seems clear that the fractional volumes of the silicone and water regions are controlled by the extent of chemical cross-linking. SiHG lenses have the remarkable property of containing regions which are nearly 100% silicone or 100% water [37–38], which implies the presence of an interface throughout the structure which is similar to the membrane-water interface. We recognized these interface regions could be used to bind amphipathic H-ISFs. For the experiments in this report we used two SiHG lenses which are in the middle range of water content, which are Stenfilcon A (Aspire) and Comfilcon A (Biofinity). Comfilcon A is a third generation SiHG with high Dk values even with a silicone content of 52% and are approved for 30 days of continuous wear [70–71].

Figure 5.

(A), Typical monomer for a silicone hydrogel contact lens. (B), Water content and Dk values of HG and SiHG lenses. LA, Lotrafilcon A; LB, Lotrafilcon B; G, Galyfilcon A; C, Comfilcon A; S, Stenfilcon A; N, Nelficon A.

Demonstration of interface regions in SiHG contact lenses

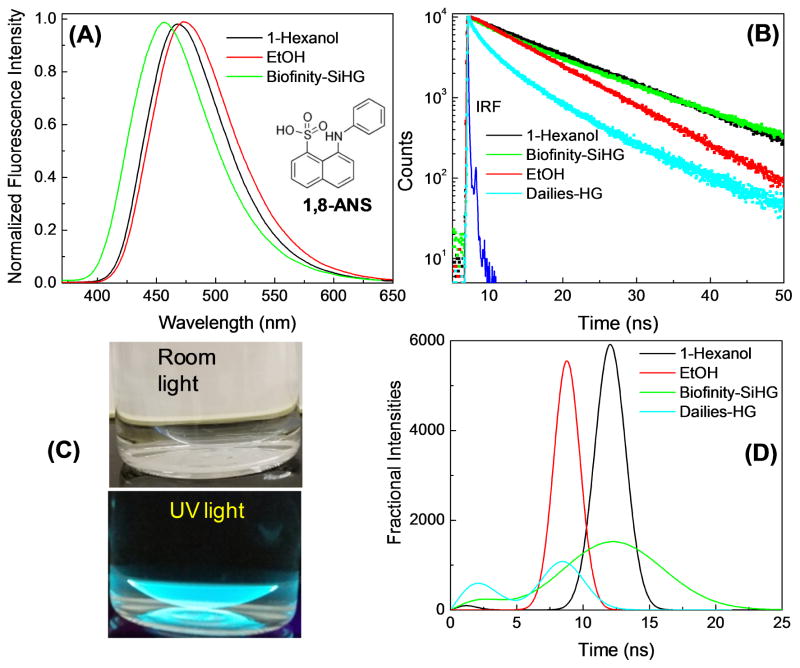

We used the polarity-sensitive fluorophore 1-anilino-8-naphthalene sulfonic acid (1,8-ANS) to test for binding of an amphipathic molecule to a Biofinity SiHG contact lens (Figure 6). As is typical of ANS-like probes there is almost no fluorescence in water [72–73]. We found that 1,8-ANS becomes highly fluorescent when bound to the SiHG lens. The emission spectra shown in Figure 6A are normalized because it is difficult to position a lens in an exact position, which is not a problem with a fluid-filled 1 cm x 1 cm cuvette. The emission maximum of 1,8-ANS in the Biofinity contact lens is blue-shifted to a greater extent than in 1-hexanol. The 11.2 ns decay time in the lens is comparable to that in 1-hexanol. These spectral properties are consistent with 1,8-ANS being in a completely non-polar region and not exposed to the quenching effects of water [74–75]. The blue-shift and decay times of 1,8-ANS are larger than those observed for similar probes when bound to lipid bilayers [76–77]. It is likely that the highly charged sulfonic acid moiety remains in the aqueous phase. This result indicates that the silicone-to-water interface is sharply defined with the change in polarity occurring over a distance which is smaller than the polar side chain region of a phospholipid bilayer which is less than 1 nm [78–79]. Much weaker emission from 1,8-ANS was found using the Dailies HG lens (not shown), which was almost as weakly fluorescent as 1,8-ANS in water. The low quantum yield of 1,8-ANS with the HG lens is confirmed by its more rapid intensity-decay and shorter decay time (Figure 6B). These results demonstrated the existence of a polar to non-polar interface region in SiHGs, and such regions are not present in HG lenses.

Figure 6.

(A), Normalized emission spectra of 1,8-ANS in 1-hexanol, ethanol and Biofinity contact lens. ANS emission in Dailies-HG is too weak to measure emission spectrum, λex = 350 nm. (B), Fluorescence intensity decays of 1,8-ANS in 1-hexanol, ethanol and bound to a SiHG (Biofinity) and a HG (Dailies) contact lens. λex = 355 nm. Inset in (A) shows molecular structure of 1,8-ANS. (C), photographs of ANS doped contact lens with no emission filter, in room light and on a hand-held UV lamp. (D), Lifetime distribution analysis of 1,8-ANS in 1-hexanol, ethanol, and 1,8-ANS labeled Biofinity -SiHG or Dailies -HG.

Additional information about the environment of 1,8-ANS when bound to lenses was obtained from the lifetime-distribution analysis of the intensity decays (Figure 6D). The decay times from 1,8-ANS in the pure solvents such as 1-hexanol and ethanol were found to be single and relatively narrow lifetime distributions. The lifetime distribution in the HG lens is bi-modal with short decay times near 3 and 6 ns. Components with shorter decay times were present (not shown) but could not be resolved with the impulse response function of our instrument. The lifetime distribution of 1,8-ANS in Biofinity lens is somewhat surprising for the highly blue-shifted emission spectrum. There is a small curvature in the intensity decay (Figure 6B) which causes the wider lifetime mode centered at 10 ns. This result indicates the 1,8-ANS bound to a SiHG lens may exist in a range of mostly non-polar environments. Another possible and likely explanation is that the emission spectrum undergoes a time-dependent spectral shift due to relaxation of the local environment around the higher dipole moment in the excited state [80–81]. Additional experimentation is required to distinguish between these static and dynamic models for the lifetime distribution of 1,8-ANS in the SiHG lenses.

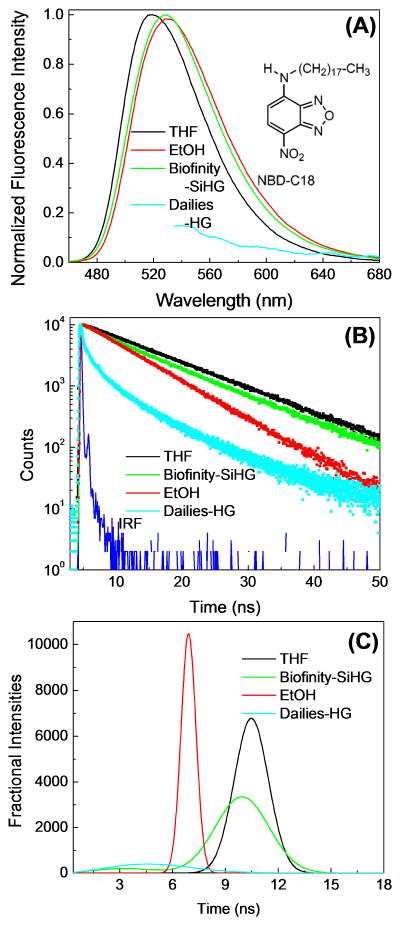

Use of a C18 hydrophobic side chain for binding to SiHG lenses

Because of its low fluorescence in water we did not expect fluorescence for 1,8-ANS in the bulk phase when not bound to the SiHG lenses. Hence the results in Figure 6 do not exclude the possibility of unbound ANS in the water surrounding the lens. Hydrophobic fluorophores are known to bind to SiHG lenses [82–83], but we did not know if a single C18 side chain would provide complete binding to the SiHG lenses with no detectable fluorophore in the surrounding aqueous phase. We tested the extent of binding using a derivative of the water-soluble probe NBD with a C18 side chain (Figures 4 and 7). We found the emission spectrum (Figure 7A) of NDB-C18 when bound to the SiHG contact lenses to be blue shifted comparable to that observed in the non-polar solvent tetrahydrofuran (THF) or when bound to phospholipid bilayers [84]. The fluorescence lifetime in the contact lens is almost identical to that observed in THF (Figure 7B). A much weaker intensity and shorter lifetime was observed for NBC-C18 bound to the Dailies HG lenses. The lifetime distribution analysis for NBD-C18 showed narrow lifetime distributions in the pure solvents, and a slightly wider distribution in the SiHG lens (Figure 7C). As for 1,8-ANS this small increase in width can be due to either ground-state heterogeneity or a time-dependent process in the excited state.

Figure 7.

(A), Normalized emission spectra with λex at 450 nm and (B), Intensity decays of NBD-C18 in THF, EtOH, Dailies-HG and a Biofinity SiHG contact lenses with λex at 473 nm. (C) NBD-C18 lifetime distribution in Biofinity-SiHG or Dailies-HG. The lifetime distribution in THF and EtOH shows single Gaussian distribution with a peak maximum at 10.5 and 6.9 ns, respectively.

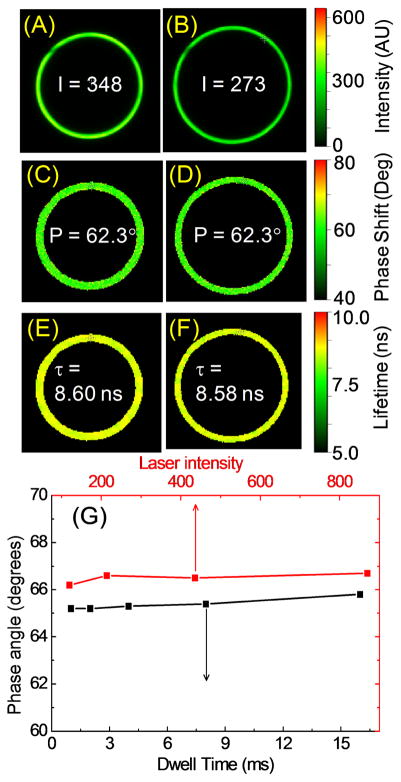

FLIM of NBD-C18

Binding of NBD-C18 to the SiHG lens was demonstrated by laser scanning confocal fluorescence intensity and lifetime images. The NBD-C18 images appear as rings because of the confocal optics and the cone shape of the lens (Figure 8). The images show the probe is uniformly distributed both in the x–y plane. The confocal image had similar intensities for different locations along the z-axis (not shown) which shows NBD-C18 is uniformly distributed throughout the lens. There was essentially no emission from the aqueous phase surrounding the lens, which demonstrates a single C18 chain provides strong binding to SiHG lenses. The IPN channels are not seen due to their sub-wavelength dimensions. For research and clinical purposes it may not be practical to use the fluorescence intensity, which will change due to eye motions and geometric optical factors. These effects can be avoided by the use of fluorescence measurements which are independent of total intensity, such as wavelength-ratiometric or lifetime-based sensing [85–87]. In Figure 8 the decay times were determined in the frequency-domain (FD), that is by the phase angle delay of the emission relative to the incident light [88–89]. The lower panel shows the phase angles remain constant over a 10-fold range of incident intensities and data collection times from 1 to 16 ms. In other time-domain (TD) experiments we found the same decay times for a different fluorophore to be constant over a 100-fold range of incident light intensities or data collection times (not shown). These results demonstrate that either TD or FD measurements can provide rapid lifetime measurements even if the total intensity is changing.

Figure 8.

Laser scanning confocal intensity images of NBD-C18 labeled Biofinity-SiHG lens at (A), 300; (B), 450 μm below the top center of lens and respective (C and D), phase shift and lifetime images (E and F). (G), Effect of the dwell time and incident intensities on the emission phase angles at 40 MHz. Phase angles are slightly offset for clarity. λex = 443 nm. Emission collected using a bandpass filter 525/50.

pH response of 6HQ-C18

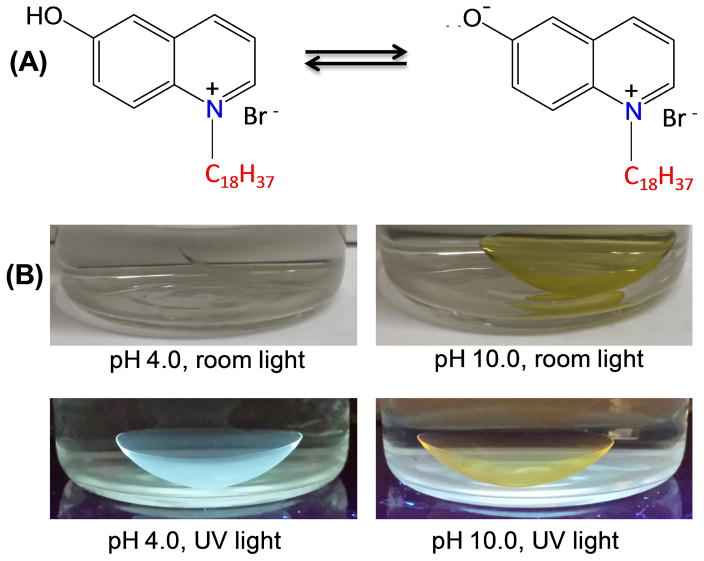

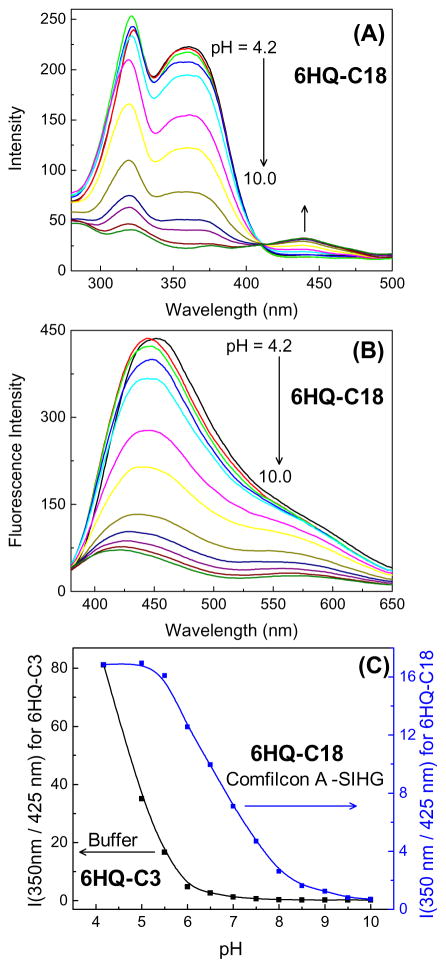

Among the ionic species in tears (Table 1), pH is the least frequently measured because the low H3O+ concentrations make a negligible contribution to the total osmolarity. Additionally, it is difficult to collect enough tear fluid to measure the pH, and contact with the eye disturbs the electrolyte concentrations [90]. However, tear pH values may become a useful diagnostic measurement because many biological processes can affect the pH. To obtain an H-ISF (6HQ-C18) from 6HQ we attached a C18 side chain to the nitrogen atom in the aromatic ring (Figure 4). The hydroxyl group, which provides the sensitivity to pH, was not modified (Figure 9A). This probe binds strongly to SiHG lenses and could not be washed out by repeated rinsing (not shown). The neutral form in low-pH media displays bright blue emission and the anionic form in high pH buffer exhibits a weaker yellow emission. Both emissions can be easily seen even in the presence of bright ambient laboratory lighting (Figure 9). When bound to a Biofinity contact lens, 6HQ-C18 displays pH-dependent changes in both the absorption and emission spectra (Figure 10). Since both absorption and emission spectra change the pH can be measured using either the excitation or emission intensity ratios. The mid-point of the transition for 6HQ-C18 was near 6.5–7.0, which is 2 log units higher than observed for a water-soluble version of the same probe, 6HQ-C3 (Figure 10C). This is a favorable result because the pKa is shifted to a value closer to physiological pH. This shift in the pKa suggests that the 6HQ moiety is either partially buried in the silicone region of the lens or proton dissociation is restricted to some extent by the silicone-water interface.

Figure 9.

(A) pH dependent equilibrium between neutral and anionic form of 6HQ-C18. (B) Photographs of 6HQ-C18 labeled biofinity CL in pH 4.0 (left) and 10 (right) under room light or on a UV handlamp.

Figure 10.

Excitation (A) and emission (B) spectra of 6HQ-C18 in Comfilcon A lens. (C), pH-dependent excitation wavelength ratio for 6HQ-C3 in buffer and 6HQ-C18 within Comfilcon A -SiHG lens. Emission monitored at 580 nm and λex = 350 nm.

A chloride-sensitive contact lens

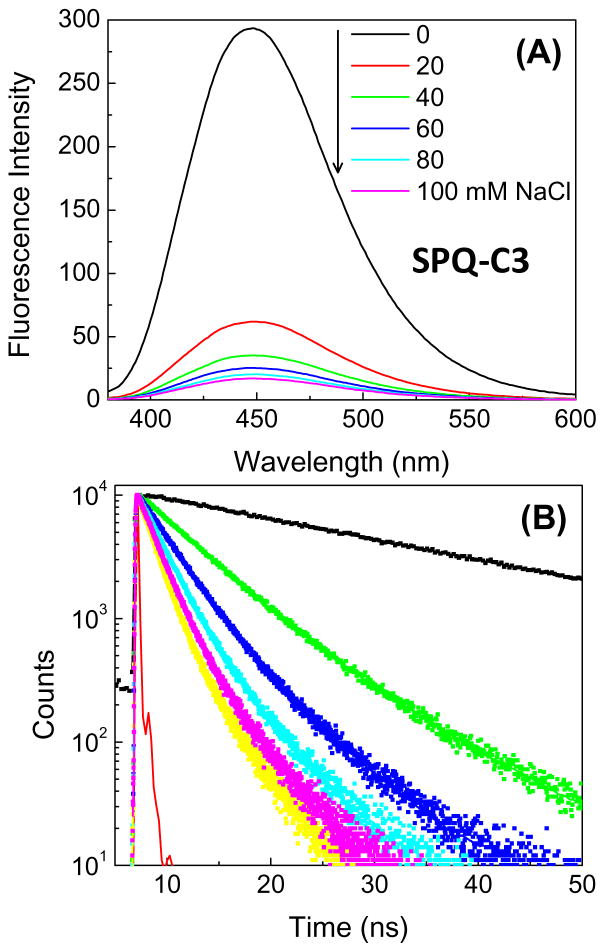

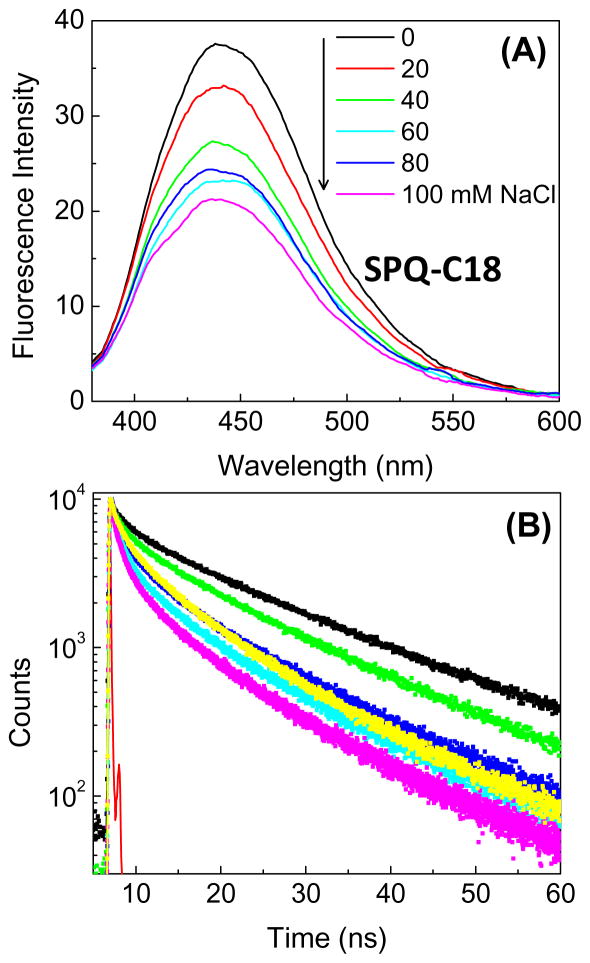

Chloride is present at high concentrations in tears, and is the dominant anion (Table 2), and the chloride concentration is needed to calculate the total osmolarity. The mechanism for chloride sensing is different from the dissociation reaction for 6HQ-C18. A typical water-soluble probe for chloride ion is SPQ-C3 (Figure 4), which undergoes collisional quenching with chloride ion [91–95]. The extent of quenching depends on the frequency of collisional constant between chloride and SPQ-C3 due to diffusion and exposure of the probe to diffusive contact with chloride ions. The intensity of water-soluble SPQ-C3 decreases dramatically in the presence of chloride (Figure 11). The decreased lifetime in the presence of chloride proves the process is collisional quenching [33]. In aqueous solution SPQ-C3 is too sensitive to chloride because it is almost completely quenched at 100 mM chloride concentration, and the chloride concentration in tears is about 118–138 mM (Table 2). We reasoned that the amount of quenching could be reduced in a SiHG contact lens because collisions could only occur from half of the total solid angle, and the probe may be partially buried in the lens polymer. To obtain an H-ISF version of SPQ which binds to SiHG lenses, we attached a C18 side chain to nitrogen atom of 6-methoxy quinoline (Figure 4). When SPQ-C18 bound to a SiHG lens the extent of quenching is about 7-fold less than SPQ-C3. SPQ-C18 is about 50% quenched at 100 mM Cl ion concentration (Figure 12), so it will remain fluorescent even in the presence of physiological chloride concentrations of 140 mM and will be sensitive to changes in chloride concentrations in the physiological range.

Figure 11.

Chloride quenching of SPQ-3 in water. A, emission spectra and B, Time-dependent decays. λex = 355 nm.

Figure 12.

Chloride quenching of SPQ-18 in a Stenfilcon A (Aspire) contact lens. (A), emission spectra and (B), time-dependent decays. λex = 355 nm.

The bimolecular quenching constant for SPC-C3 in water is 5.4 × 109 M−1 sec−1 (Figure 13). This value is consistent with the known diffusion constant of chloride in water and with a quenching efficiency of 100%, which means every diffusive contact results in quenching [96–97]. The Bimolecular quenching constant for SPQ-C18 bound to the contact lens is 1 × 109 M−1 sec−1, which is a 5.4 decrease in the collision rate of SPQ-C3 in water. This is a favorable result for an electrolyte contract lens because binding of SPQ-C18 to the SiHG lens results in a H-ISF which is most sensitive to chloride concentrations present in tears.

Figure 13.

Comparison of lifetime Stern-Volmer plots for SPQ-C3 in water and SPQ-C18 in a Stenfilcon A (Aspire) contact lens.

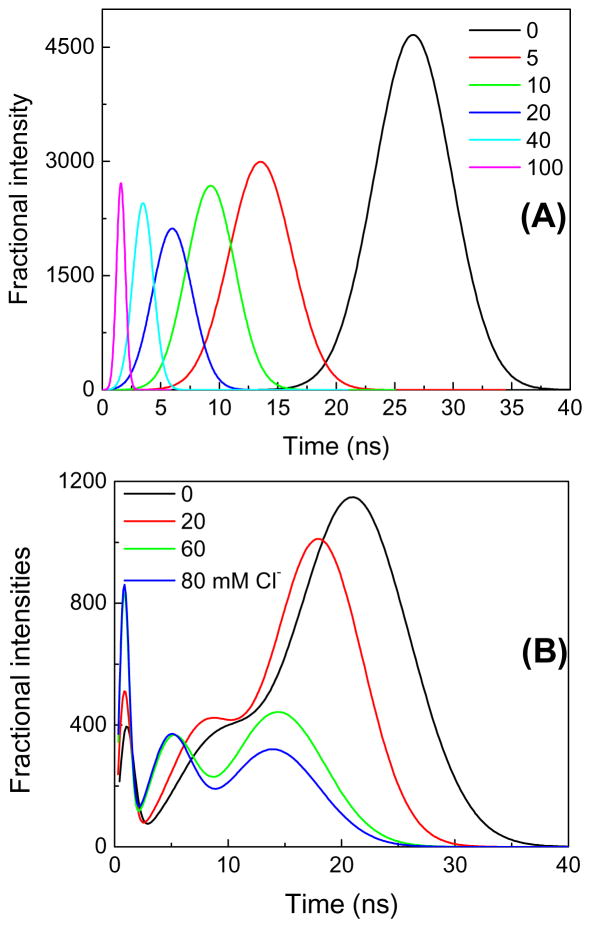

Comparison of Figures 11 and 12 reveals the intensity decays for SPQ-C18 in the Aspire contact lens are more heterogeneous than for SPQ-C3 in water. In the presence of chloride the decay of SPQ-C3 remains mostly a single exponential decay, but the decay of SPQ-C18 in the Stenfilcon lens becomes multi- or non-exponential. We found the lifetime-distribution analysis to be informative. For SPQ-C3 in water we found a single peak in the distribution starting near 26 ns in the absence of chloride, which decreases to 1.7 ns with 100 mM chloride (Figure 14A). A single peak of modest width indicates the decay is mostly a single exponential. In contrast SPQ-C18 in the contact lens shows several peaks in the lifetime distribution (Figure 14B), which can indicate the presence of SPQ-C18 in more than a single environment. At all chloride concentrations there were two or three dominant decay times. There appears to be a fraction of the SPQ-C18 molecules which display lifetimes of 14–24 ns even in the presence of high chloride concentrations, and thus somewhat shielded from chloride. Another population is seen to be strongly quenched with decay components near 1 ns or less with 80 mM chloride (Figure 14B). A single exponential intensity decay is not necessary for a clinical measurement of chloride concentrations. Even with complex decays a mean decay time from a time domain (TD) measurement or a phase angle at a single frequency from a frequency-domain (FD) instrument is adequate to determine the analyte concentration [98–99].

Figure 14.

(A), Lifetime distribution analysis of SPQ-C3 in water and (B) SPQ-C18 in Stenfilcon A (Aspire) with chloride quenching.

In summary, we have described an approach to place sensing fluorophores in SiHG contact lenses, while maintaining the ability to sense individual ionic species. Water-soluble probes are already known for the dominant electrolytes in tears. Our approach allows rational design of H-ISFs for these ions, and for creation of a contact lens which can report the total electrolyte profile of tears.

Acknowledgments

This work was also supported by grants from the National Institute of Health (GM107986, EB006521, EB018959 and OD019975). The authors thank Dr. Liangfu Zhu and Dr. Douguo Zhang for assistance with some of the artwork, Dr. Henry Szmacinski for assistance with the FLIM measurements, and Dr. Julie Rosen for critical reading.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Phadatare SP, Momin M, Nighojkar P, Askarkar S, Singh KK. A comprehensive review on dry eye diseases: diagnosis, medical management, recent developments, and future challenges. Adv Pharmac. 2015:1–12. article ID 704946. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schein OD, Munoz B, Tielsch JM, Bandeen-Roche K, West S. Prevalence of dry eye among the elderly. Am J Ophthalmol. 1997;124:723–728. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(14)71688-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gayton JL. Etiology, prevalence, and treatment of dry eye disease. Clin Ophthalmol. 2009;3:405–412. doi: 10.2147/opth.s5555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Smith JA. The epidemiology of dry eye disease. Acta Ophthalmol. 2007;85(240) [Google Scholar]

- 5.Smith JA., Chair Report of the Epidemiology Subcommittee, Intl. Dry Eye Workshop (2007) DEWS Epidemiology. 2007:93–107. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bhavsar AS, Bhavsar SG, Jain SM. A review on recent advances in dry eye: Pathogenesis and management. Oman J Ophthalmol. 2011;4(2):50–56. doi: 10.4103/0974-620X.83653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Foulks GN, Bron AJ. Meibomian gland dysfunction: A clinical scheme for description, diagnosis, classifiation and grading. Ocular Sur. 2003;1(3):107–126. doi: 10.1016/s1542-0124(12)70139-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Damato BE, Allan D, Murray SB, Lee WR. Senile atrophy of the human lacrimal gland: the contribution of chronic inflammatory disease. Br J Ophthalmol. 1984;68:674–380. doi: 10.1136/bjo.68.9.674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tuominen IS, Konttinen YT, Vesaluoma MH, Moilansen JAO, Helinto M, Tervo TMT. Corneal innervation and morphology in primary Sjogren’s syndrome. Invest Opthal Vis Sci. 2003;44(6):2545–2549. doi: 10.1167/iovs.02-1260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tarabishy AB, Jeng BH. Bacterial conjunctivitis: A review for internists. Cleve J Med. 2008;75(7):507–512. doi: 10.3949/ccjm.75.7.507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Garcia-Porta N, Rico-del-Viejo L, Martin-Gil A, Carracedo G, Pintor J, Gonzalez-Meijome M. Differences in dry eye questionnaire symptoms in two different modalities of contact lens wear: silicone hydrogel in daily wear basis and overnight orthokeratology. BioMed Intl. 2016 doi: 10.1155/2016/1242845. 1242845:1/9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chalmers RL, Begley CG. Dryness symptoms among an unselected clinical population with and without contact lens wear. Contact Lens Ant Eye. 2006;29:25–30. doi: 10.1016/j.clae.2005.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Versura P, Profazio V, Campos EC. Performance of tear osmolarity compared to previous diagnostic tests for dry eye diseases. Curr Eye Res. 2010;35(7):553–564. doi: 10.3109/02713683.2010.484557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Najafi L, Malek M, Valojerdi AE, Khamseh ME, Aghaei H. Dry eye disease in type 2 diabetes mellitus; comparison of the tear osmolarity tests with other common diagnostic tests: a diagnostic accuracy study using STARD standard. J Diab Metab Dis. 2015;14:1–8. doi: 10.1186/s40200-015-0157-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tomlinson A, Khanal S, Ramaesb K, Diaper C, McFadyen A. Tear film osmolarity: determination of a referent for dry eye diagnosis. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2006;47(10):4309–4315. doi: 10.1167/iovs.05-1504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Roy NS, Kuklinski E, Asbell PA. The growing need for validated biomarkers and endpoints for dry eye clinical research. Inves Ophthal Vis Sci. 2017:B101–B109. doi: 10.1167/iovs.17-21709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jackson DC, Zeng W, Wong CY, Mifsud EJ, Williamson NA, Ang CS, Vingrys AJ, Downie LE. Tear interferon gamma as a biomarker for evaporative dry eye disease. Invest Ophthal Vis Sci. 2017;57:4824–4830. doi: 10.1167/iovs.16-19757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Song H, Zhang M, Hu X, Li K, Jiang X, Liu Y, Lv H, Li X. Correlation analysis of ocular symptoms and signs in patients with dry eye. J Ophthalmol. 2017 doi: 10.1155/2017/1247138. 1247138:1/9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ozcura F, Aydin S, Helvaci MR. Ocular surface disease index for the diagnosis of dry eye syndrome. Ocu Immunol Inflam. 2007;15:389–393. doi: 10.1080/09273940701486803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dana R, Chauhan SK, Stevenson W. Dry eye disease - an immune-mediated ocular surface disorder. Arch Ophthalmol. 2012;130:90–100. doi: 10.1001/archophthalmol.2011.364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pflugfelder SC. Anti-inflammatory therapy of dry eye. The Ocular Surface. 2003;1(1):31–36. doi: 10.1016/s1542-0124(12)70005-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gorbet M, Postnikoff C, Williams S. The noninflammatory phenotype of neutrophils from the closed eye environment: A flow cytometry analysis of receptor expression. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2015;56:4582–4591. doi: 10.1167/iovs.14-15750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Demaurex N, Schrenzel J, Jaconi ME, Lew DP, Krause K. Proton channels, plasma membrane potential, and respiratory burst in human neutrophils. Eur J Haematology. 1993;51(5):309–312. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0609.1993.tb01613.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.van Zwieten R, Wever R, Hamers MN, Weening RS, an Roos D. Extracellular proton release by stimulated neutrophils. J Clin Invest. 1981;66(1):310–313. doi: 10.1172/JCI110250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bachman WG, Wilson G. Essential ions for maintenance of the corneal eipithelial surface. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1985;26:1484–1488. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ubels JL, Hoffman HM, Srikanth S, Resau JH, Webb CP. Gene expression in rat lacrimal gland duct cells collected using laser capture microdissection: Evidence for K+ secretion by duct cells. Invest Opthalmol Vis Sci. 2006;47:1876–1885. doi: 10.1167/iovs.05-0363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ruiz-Ederra J, Levin MH, Verkman AS. In situ fluorescence measurement of tear film (Na+], [K+], [Cl−], and pH in mice show marked hypertonicity in aquaporin-5 deficiency. Invest Ophthal Vis Sci. 2009;50:2132–2138. doi: 10.1167/iovs.08-3033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yoon D, Gadaria-Rathod N, Oh C, Asbell PA. Precision and accuracy of TearLab osmometer in measuring osmolarity of salt solutions. Curr Eye Res. 2014;39(12):1247–1250. doi: 10.3109/02713683.2014.906623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wang XD, Wolfbeis OS. Fiber-optic chemical sensors and biosensors (2008–2012) Anal Chem. 2013;85:487–508. doi: 10.1021/ac303159b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Thompson RB, editor. Fluorescence Sensors and Biosensors. Taylor & Francis; New York: 2006. p. 394. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Crossley R, Goolamali Z, Gosper JJ, Sammes PG. Synthesis and spectral properties of new fluorescent probes for potassium. J Chem Soc Perkin Trans. 1994;2:513–520. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Grynkiewicz G, Poenie M, Tsien RY. A new generation of Ca2+ indicators with greatly improved fluorescen properties. J Biol Chem. 1985;260(6):3440–3450. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lakowicz JR. Principles of Fluorescence Spectroscopy. 3. Chapter 8. Springer; New York: 2006. pp. 954pp. 277–330. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Doutch JJ, Wquantock AJ, Joyce NC, Meek KM. Ultraviolet light transmission through the human corneal stroma is reduced in the periphery. Biophys J. 2012;102:1258–1264. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2012.02.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Osama IMA, Takashi K, Hitomi WT, Murat D, Yukihiro M, Yoko O, Junko O, Kazuno N, Jun S, Yasuo S, et al. Corneal and retinal effects of ultraviolet B exposure in a soft contact lens mouse model. Invest Opthal Vis Sci. 2012;53(4):2403–2413. doi: 10.1167/iovs.11-6863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Harris MG, Chin RS, Lee DS, Tam MH, Dobkins CE. Ultraviolet transmittance of the vistakon disposable contact lenses. Contact Lens Ant Eye. 2000;23:10–15. doi: 10.1016/s1367-0484(00)80035-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kennedy JP, Subramanyam U. Polymer networks, producing crosslinking polyvinyl alcohol-polysiloxanes, and products and films made from networks. US 20100305231A1 20101202 US Pat Appl Publ (2010) 2010

- 38.Chu S-H, Cheng H-H. 3D network structured silicon containing prepolymer and method for its manufacture. US 20150252194 A1 20150910 US Pat Appl Publ. 2015

- 39.Ohashi Y, Dogru M, Tsubota K. Laboratory findings in tear fluid analysis. Clin Chim Acta. 2006;369:17–28. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2005.12.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Guan L, Jimenez MEG, Walowski C, Boushehri A, Prausnitz JM, Radke CJ. Permeability and partition coefficient of aqueous sodium chloride in soft contact lenses. J Appl Polym Sci. 2011;122:1457–1471. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Erdodi G, Kennedy JP. Amphiphilic conetworks: Definition, synthesis, applications. Prog Polym Sci. 2006;31:1–18. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wang J, Li X. Preparation and characterization of interpenetrating polymer network silicone hydrogels with high oxygen permeability. J Appl Polymer Sci. 2010;116:2749–2757. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Shimizu T, Goda T, Minoura N, Takai M, Ishihara I. Super-hydrophilic silicone hydrogels with interpenetrating poly(2-methacryloxyloxyethyl phosphorylcholine) networks. Biomaterials. 2010;31:3274–3280. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2010.01.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bar N, Ramanjaneyulu K, Basak P. Quasi-Solid semi-interpenetrating polymer networks as electrolytes: Part I. Dependence of physicochemical characteristics and Ion conduction behavior on matrix composition, cross-link density, chain length between cross-links, molecular entanglements, charge carrier concentration, and nature of anion. J Phys Chem C. 2014;118:159–17. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Silicone hydrogels - What are they and how should they be used in everyday practice? Bausch & Lomb, CIBA Vision, Contact Lens Monthly. 218(5726) [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gromacki SJ. Compliance with daily disposable contact lenses. Contact Lens Spectrum/Special Edition. 2013:13. www.cispectrum.com.

- 47.Subbaraman LN, Jones LW. Measuring friction and lubricity of soft contact lenses: A review. Contact Lens Spectrum, Volume:, Issue: June 2013. 2013 www.cispectrum.com.

- 48.Fonn D. The clinical relevance of contact lens lubricity. Contact Lens Spectrum Special Edition. 2013:25–27. www.cispectrum.com.

- 49.El Gamal A, Eltoukhy H. CMOS image sensors. IEEE Cir Dev Mag. 2005;21(3):8755–3996. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hain R, Kahler CJ, Tropea C. Comparison of CCD, CMOS and intensified cameras. Exp Fluids. 2007;42(3):403–411. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Janesick J, Putnam G. Developments and applications of high performance CCD and CMOS imaging arrays. Annu Rev Nuc Particle Sci. 2003;53:263–300. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Beier HT, Ibey BL. Experimental comparison of the high-speed imaging performance of an EM-CCD and sCMOS camera in a dynamic live-cell imaging test case. PloS One. 2014;9:e84614-1/6. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0084614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Saruabh S, Maji S, Bruchez MP. Evaluation of sCMOS cameras for detection and localization of single Cy5 molecules. Optics Exp. 2012;20(7):7338–7349. doi: 10.1364/OE.20.007338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Charbon E. Towards large scale CMOS single-photon detector arrays for lab-on-chip applications. J Phys D: Appl Phys. 2008;41:094010-1/9. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Mattioli Della Rocca F, Nedbal J, Tyndall D, Krstajic N, Day-Uei Li D, Ameer-Beg SM, Henderson RK. Real-time fluorescence lifetime actuation for cell sorting using a CMOS SPAD silicon photomultiplier. Optics Letts. 2016;41(4):673–676. doi: 10.1364/OL.41.000673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Rae BR, Muir KR, Gong Z, McKendry J, Girkin JM, Gu E, Renshaw D, Dawson MD, Henderson RK. A CMOS time-resolved fluorescence lifetime analysis micro-system. Sensors. 2009;9:9255–9274. doi: 10.3390/s91109255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Li DDU, Arit J, Tyndall D, Walker R, Richardson J, Stoppa D, Charbon E, Henderson RK. Video-rate fluorescence lifetime imaging camera with CMOS single-photon avalanche diode arrays and high-speed imaging algorithm. J Biomed Optics. 2011;16(9):096012-1/12. doi: 10.1117/1.3625288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tango_(platform)

- 59.Ray K, Badugu R, Lakowicz JR. Langmuir-Blodgett Monolayers of Long-Chain NBD Derivatives on Silver Island Films: Well-Organized Probe Layer for the Metal-Enhanced Fluorescence Studies. J Phys Chem B. 2006;110:13499–13507. doi: 10.1021/jp0620623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Badugu R, Lakowicz JR, Geddes CD. Fluorescence sensors for monosaccharides based on the 6-methylquinolinium nucleus and boronic acid moiety: application to ophthalmic diagnostics. Talanta. 2005;66:569–574. doi: 10.1016/j.talanta.2004.08.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Badugu R, Lakowicz JR, Geddes CD. Boronic acid fluorescent sensors for monosaccharide signaling based on the 6-methoxy-quinolinium heterocyclic nucleus: progress toward noninvasive and continuous glucose monitoring. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2005;15:3974–3977. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2004.09.058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Grinvald A, Steinberg IZ. On the analysis of fluorescence decay kinetics by the method of least-squares. Anal Biochem. 1974;59:583–593. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(74)90312-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.O’Connor DV, Phillips D. Time-correlated single-photon counting. Academic Press; New York: 1984. p. 288. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Alcala JR, Gratton E, Prendergast FG. Fluorescence lifetime distributions in proteins. Biophys J. 1987;51:597–604. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(87)83384-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Lakowicz JR, Cherek H, Gryczynski I, Joshi N, Johnson ML. Analysis of fluorescence decay kinetics measured in the frequency-domain using distribution of decay times. Biophys Chem. 1987;28:35–50. doi: 10.1016/0301-4622(87)80073-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Efron N, Morgan PB, Cameron ID, Brennan NA, Goodwin M. Oxygen permeability and water content of silicone hydrogel contract lens materials. Opto Vis Scil. 2007;84:e328–e337. doi: 10.1097/OPX.0b013e31804375ed. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Nicolson PC, Vpogt J. Soft contact lens polymers: an evolution. Biomat. 2001;22:3273–3283. doi: 10.1016/s0142-9612(01)00165-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.French K, Jones L. A decade with silicone hydrogels: Part 1. Opto Today. 48:42–46. (216) [Google Scholar]

- 69.Morgan PB, Woods C, Tranoudis I, et al. International contact lens prescribing in 2011. Contact Lens Spectrum. 2012;27:26–31. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Brennan NA, Coles MLC, Connor HRM, McIllroy RG. A 12-month prospective clinical trial of comfilcon A silicone-hydrogel contact lenses worn on a 30-day continuous wear basis. Lens Ant Eye. 2007;30:108–118. doi: 10.1016/j.clae.2007.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Moezi A, Fonn DM, Simpson TI. Overnight corneal swelling with silicone hydrogel contact lenses with high oxygen transmissibility. Eye Cont Lens. 2006;32:277–280. doi: 10.1097/01.icl.0000224529.14273.26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Daniel E, Weber G. Cooperative effects in binding by bovine serum albumin i: the binding of 1-anilino-8-naphthalensulfonate, fluorometric titrations. Biochem. 1966;5:1893–1900. doi: 10.1021/bi00870a016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Slavik J. Anilinonaphthalene sulfonate as a probe of membrane composition and function. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1982;694:1–25. doi: 10.1016/0304-4157(82)90012-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Dobretsov GE, Syrejschikova TI, Smolina NV. On mechanisms of fluorescence quenching by water. Biophysics. 2014;59(2):183–188. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Ebbesen TW, Chiron CA. Role of specific solvation in the fluorescence sensitivity of 1,8-ANS to water. J Phys Chem. 1989;93:7139–7143. [Google Scholar]

- 76.Badea MG, DeToma RP, Brand L. Nanosecond relaxation processes in liposomes. Biophys J. 1978;24:197–212. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(78)85356-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Lakowicz JR, Hogen D. Dynamic properties of the lipid-water interface of model membranes as revealed by lifetime-resolved fluorescence emission spectra. Biochem. 1981;20:1366–1373. doi: 10.1021/bi00508a051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Lewis BA, Engelman DM. Lipid bilayer thickness varies linearly with acyl chain length in fluid phosphatidylcholine vesicles. J Mol Biol. 1983;166(2):211–217. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(83)80007-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Balgavy P, Dubnickova M, Kucerka N, Kiselev MA, Yaradalkin SP, Uhrikova D. Bilayer thickness and lipid interface area in unilamellar extruded 1,2-diacylphosphatidylcholine lipsomes: a small-angle neutron scattering study. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2001;1512(1):40–52. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2736(01)00298-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Easter JH, DeToma RP, Brand L. Nanosecond time-resolved emission spectroscopy of a fluorescence probe adsorbed to L-α-egg lecithin vesicles. Biophys J. 1976;16:571–583. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(76)85712-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Lakowicz JR, Gratton E, Cherek H, Maliwal BP, Laczko G. Determination of time-resolved fluorescence emission spectra and anisotropies of a fluorophore-protein complex using frequency-domain phase-modulation fluorometry. J Biol Chem. 1984;259:10967–10972. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Dursch TJ, Liu DE, Oh Y, Radke CJ. Fluorescent solute-partitioning characterization of layered soft contact lenses. Acta Biomat. 2015;15:48–54. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2014.11.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Liu DE, Dursch TJ, Oh Y, Bregante DT, Chan SY, Radke CJ. Equilibrium water and solute uptake in silicone hydrogels. Acta Biomat. 2015;18:112–117. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2015.02.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Chattopadhyay A, Mukherjee S. Red edge excitation shift of a deeply embedded membrane probe: implications in water penetration I nthe bilayer. J Phys Chem B. 1999;103:8180–8185. [Google Scholar]

- 85.Lakowicz JR, Szmacinski H, Nowaczyk K, Lederer WJ, Kirby MS, Johnson ML. Fluorescence lifetime imaging of intracellular calcium in COS cells using Quin-2. Cell Calcium. 1994;15:7–27. doi: 10.1016/0143-4160(94)90100-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Lakowicz JR, Szmacinski H, Nowaczyk K, Berndt KW, Johnson ML. Fluorescence lifetime imaging. Anal Biochem. 1992;202:316–330. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(92)90112-k. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Lakowicz JR, Szmacinski H, Nowaczyk K, Johnson ML. Fluorescence lifetime imaging of calcium using Quin-2. Cell Calcium. 1992;13:131–147. doi: 10.1016/0143-4160(92)90041-p. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Lakowicz JR, Maliwal BP. Construction and performance of a variable-frequency phase-modulation fluorometer. Biophys Chem. 1985;21:61–78. doi: 10.1016/0301-4622(85)85007-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Gratton E, Limkeman M, Lakowicz JR, Maliwal B, Cherek H, Laczko G. Resolution of mixtures of fluorophores using variable-frequency phase and modulation data. Biophys J. 1984;46:479–486. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(84)84044-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Carney LG, Mauger TF, Hill RM. Buffering in human tears: pH responses to acid and base challenge. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1989;30:747–754. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Rahmani S, Mohammadi NM, Akbarzadeh BA, Nazari MR, Ghassemi-Broumand M. Spectral transmittance of UV-blocking soft contact lenses: a comparative study. Cont Lens Ant Eye. 2014;37(6):451–454. doi: 10.1016/j.clae.2014.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Verkman AS. Development and biological applications of chloride-sensitive fluorescent indicators. Am J Physiol. 1990;253:C375–C388. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1990.259.3.C375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Verkman AS, Sellers MC, Chao AC, Leung T, Ketchman R. Synthesis and characterization of improved chloride-sensitive fluorescent indicators for biological applications. Anal Biochem. 1989;178:355–361. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(89)90652-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Biwersi J, Tulk B, Verkman AS. Long-wavelength chloride-sensitive fluorescent indicators. Anal Biochem. 1994;219:139–143. doi: 10.1006/abio.1994.1242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Illsley NP, Verkman AS. Membrane chloride transport measured using a chloride-sensitive fluorescent probe. Biochemistry. 1987;26:1215–1219. doi: 10.1021/bi00379a002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Eftink MR, Jameson DM. Acrylamide and oxygen fluorescence quenching studies with liver alcohol dehydrogenase using steady-state and phase fluorometry. Biochem. 1982;21(18):4443–4449. doi: 10.1021/bi00261a039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Calhoun DB, Vanderkooi JM, Holtom GR, Englander SW. Protein fluorescence quenching by small molecules: Protein penetration versus solvent exposure. Proteins. 1986;1:109–115. doi: 10.1002/prot.340010202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Szmacinski H, Lakowicz JR. Optical measurements of pH using fluorescence lifetimes and phase-modulation fluorometry. Anal Chem. 1993;65:1668–1674. doi: 10.1021/ac00061a007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Szmacinski H, Lakowicz JR. Sodium green as a potential probe for intracellular sodium imaging based on fluorescence lifetime. Anal Biochem. 1997;250(2):131–138. doi: 10.1006/abio.1997.2203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]