INTRODUCTION

Picky eating is common in early childhood (Dovey, Staples, Gibson, & Halford, 2008) and is often raised as a concern by parents. Parents can respond to picky eating with pressuring feeding practices, with the goal of helping the child to overcome picky eating and ultimately attain more rapid growth. Although some degree of encouragement of picky eaters is likely adaptive and could be viewed as responsive parenting that is sensitive to the child’s needs, other types of pressure may be maladaptive. Specifically, pressure that is intrusive or not responsive to the child is theorized to cause increases in picky eating. In addition, some have theorized that pressure can overwhelm a child’s healthy internal hunger and satiety cues, leading to excessively rapid growth (Dovey et al., 2008; Farrow, Galloway, & Fraser, 2009; Finistrella et al., 2012; Gibson et al., 2012; Hayes et al., 2016).

Clarifying the temporality and bidirectionality of associations between picky eating, pressuring feeding, and growth, particularly in toddlerhood, would provide valuable practical and theoretical information. Toddlerhood is a developmental period during which picky eating begins to emerge (Dovey et al., 2008), and therefore during which pressuring feeding and conflict in the parent-child interaction around food often develops. Pediatric practice guidelines include a focus on reducing picky eating (Hassink, 2006) as well as limiting pressure or excessive control (Barlow & The Expert Committee, 2007). If pressuring feeding that occurs in response to a child’s picky eating leads in turn to healthy growth or reductions in picky eating, this would suggest that encouraging parents to implement responsive pressure (i.e., pressure that is not intrusive or excessive) may be a valuable intervention strategy for the child who is a picky eater and/or has poor growth. If in contrast, pressuring feeding leads to increases in picky eating and further slowing of growth, this would suggest that pressuring feeding may not be a worthwhile strategy for changing the trajectory of children’s picky eating and growth.

Prior studies examining these temporal relationships have mixed results. Specifically, prior studies have found either no association between pressuring feeding and future markers of adiposity (Faith et al., 2004; Gregory, Paxton, & Brozovic, 2010; Lumeng et al., 2012; Webber, Cooke, Hill, & Wardle, 2010) or have found an inverse association (Afonso et al., 2016; M. S. Faith et al., 2004; Jansen et al., 2014; Rodgers et al., 2013; Thompson, Adair, & Bentley, 2013; Tschann et al., 2015; Ventura & Birch, 2008). Thinner child weight status has been found in several studies to predict increases in pressure (Afonso et al., 2016; Jansen et al., 2014; Thompson et al., 2013; Tschann et al., 2015; Webber et al., 2010). Several prior studies have linked pressuring feeding with picky or restrained eating concurrently (Carper, Orlet Fisher, & Birch, 2000; Carruth et al., 1998; Farrow et al., 2009; Ventura & Birch, 2008; Wardle, Carnell, & Cooke, 2005). We identified only two studies that tested the association between pressuring feeding and future picky eating, with conflicting results (Galloway, Fiorito, Lee, & Birch, 2005; Gregory et al., 2010) Picky eating has been associated with controlling or pressuring feeding in in several cross-sectional studies (Clark, Goyder, Bissell, Blank, & Peters, 2007; Faith et al., 2004; Galloway et al, 2005; Nowicka, Sorjonen, Pietrobelli, Flodmark, & Faith, 2014; Ventura & Birch, 2008), but to our knowledge this association has not been tested longitudinally.

Examining these pathways in low-income populations is especially relevant given that picky eating (Cardona Cano et al., 2015; Dubois, Farmer, Girard, Peterson, & Tatone-Tokuda, 2007; Hafstad, Abebe, Torgersen, & von Soest, 2013; Tharner et al., 2014), pressuring feeding (Shloim, Edelson, Martin, & Hetherington, 2015), and both over- and under-weight (Ogden, Lamb, Carroll, & Flegal, 2010) have all been reported to be more common in this demographic. Therefore, within a diverse cohort of low-income toddlers followed longitudinally at ages 21, 27, and 33 months, we sought to test the hypotheses that: (1) pressuring feeding predicts increases in weight-for-length z-score (WLZ); (2) lower WLZ predicts increases in pressuring feeding; (3) pressuring feeding predicts increases in picky eating; (4) picky eating predicts increases in pressuring feeding; and (5) picky eating predicts decreases in WLZ. To our knowledge, this is the first test of these associations including all constructs simultaneously in a longitudinal design.

SUBJECTS AND METHODS

Participants

Participants were recruited between 2011 and 2014 via flyers posted in community agencies serving low-income families. The study was described as examining whether children with different levels of stress eat differently. Inclusion criteria were: the biological mother was the legal guardian, had an education level less than a 4-year college degree, and was ≥ 18 years old; the family was English-speaking and was eligible for Head Start, Women, Infants and Children (WIC) Program, or Medicaid; and the child was born at a gestational age ≥ 36 weeks, had no food allergies or significant health problems, perinatal or neonatal complications, or developmental delays, and was between 21 and 27 months old. Mothers provided written informed consent. The University of Michigan Institutional Review Board approved the study.

Mother-child dyads were invited to participate in three waves of data collection at child ages 21, 27, and 33 months. A total of 244 dyads participated, with 186 dyads entering the study at age 21 months and 58 entering at 27 months to maximize recruitment. This analysis was limited to those participants with complete data for all measures at a given time point, with 222 participants contributing data at at least one time point. There were 150, 166 and 136 dyads who participated at the 21, 27, and 33 months, respectively, with 76 dyads participating at all three time points. There were 101, 116 and 91 dyads that participated at only two time points (21 and 27, 27 and 33, and 21 and 33 months, respectively). There were no differences between those who completed the study versus those who did not with regard to child sex, or maternal depressive symptoms or education. However, those who did not complete the study were more likely to be Hispanic or not white than those who remained in the study (94% versus 42%, p=0.0002).

Measures

Mothers reported child sex, age, and race and ethnicity, and maternal education, and family structure. Child weight and length were measured by trained research staff. Weight-for-length was calculated and z-scored based on United States Centers for Disease Control Growth Charts. Mothers’ weight and height were measured and body mass index (BMI) calculated.

Pressuring feeding was measured with the Pressuring to Finish subscale of the Infant Feeding Styles Questionnaire (IFSQ) (Thompson et al., 2009). Items (Appendix 1) are answered on a 1 to 5 scale, with higher scores indicating more pressuring feeding and reverse scoring applied as appropriate. Responses to the 8 items are averaged to create a summary score (α = .67–.70 across age points).

There is debate in the field regarding the definition of picky eating (Dovey et al., 2008), and the construct was therefore measured using two approaches. The Children’s Eating Behavior Questionnaire-Toddler (CEBQ-T)(Carnell & Wardle, 2007) Food Fussiness subscale consists of 6 items (Appendix 1), to which mothers respond on a scale of 1=never to 5=always. Responses are averaged (α = .87–.90 across age points). The Brief Autism Mealtime Behavior Inventory (BAMBI) was designed to measure mealtime behavior problems observed in children with autism, but has strong face validity for the assessment of picky eating behaviors among toddlers (Lukens & Linscheid, 2008). Mothers responded on a scale of 1=never to 5=at almost every meal. We averaged items (Appendix 1) contributing to the original Limited Variety and Food Refusal subscales to create a Picky Eating Subscale (13 items; α = .75–.78 across age points).

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive analyses were conducted using SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC). Univariate statistics were used to describe the sample. One-way repeated measures ANOVAs and Chi square were used to test whether WLZ, pressuring feeding, or picky eating differed across 21, 27, and 33 months.

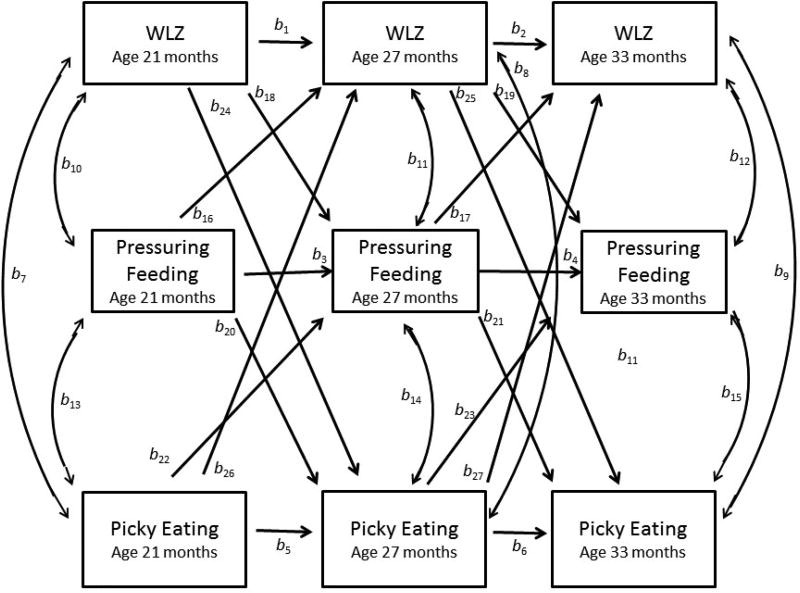

Path models were conducted (using MPLUS version 7.3; Muthen & Muthen, Los Angeles, CA) to test the concurrent, longitudinal, and cross-lagged associations between WLZ, pressuring feeding, and picky eating at ages 21, 27, and 33 months (Figure 1). This model was run twice, once using the CEBQ-T Food Fussiness subscale to measure picky eating, and once using the BAMBI Picky Eating subscale to measure picky eating. This approach estimates tracking of each construct at the individual level measured by the auto-correlation or longitudinal correlation. Bayesian estimation technique in MPLUS was used to fit models, and Bayesian posterior predictive checks (PPC) using Chi-square statistics and the corresponding posterior predictive p-values (ppp) were used to assess the goodness of fit in each model. A p value within 0.05 to 0.95 range indicate acceptable fit for the model.(Gelman, 2004)

Figure 1.

Conceptual model for longitudinal associations between WLZ, pressuring feeding, and picky eating in toddlerhood

RESULTS

Characteristics of the sample by age point are shown in Table 1. At age 21 months, the sample was 50.7% male, 48.0% non-Hispanic white, and 40.0% of mothers had a high school education or less. Demographic composition of the cohort did not change significantly across age points. WLZ, IFSQ Pressuring to Finish, and BAMBI Picky Eating did not change across age points. CEBQ Food Fussiness increased across toddlerhood.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the sample (n=222)

| 21 months | 27 months | 33 months | Test statistic (F)/chi-sq |

p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n=150 | n=166 | n=136 | |||

| Child Sex | 0.78 | .68 | |||

| Female | 74 (49.3) | 74 (44.6) | 62 (45.6) | ||

| Male | 76 (50.7) | 92 (55.4) | 74 (54.4) | ||

| Child Race/Ethnicity | 2.74 | .84 | |||

| Non-Hispanic white | 72 (48.0) | 78 (47.3) | 70 (51.5) | ||

| Non-Hispanic black | 34 (22.8) | 43 (26.1) | 34 (25.0) | ||

| Hispanic (any race) | 15 (10.1) | 19 (11.5) | 14 (10.3) | ||

| Other | 28 (18.8) | 25 (15.2) | 18 (13.2) | ||

| Maternal Education | 0.24 | .89 | |||

| <= high school | 60 (40.0) | 62 (37.4) | 53 (39.0) | ||

| >High school or GED | 90 (60.0) | 104 (62.7) | 83 (61.0) | ||

| WLZ | 0.52 (1.06) | 0.41 (1.08) | 0.38 (1.00) | 0.87 | .42 |

| IFSQ Pressuring to Finish | 1.57 (0.56) | 1.51 (0.51) | 1.56 (0.60) | 0.52 | .59 |

| CEBQ-T Food Fussiness | 2.30 (0.87) | 2.46 (0.97) | 2.68 (0.96) | 6.44 | .002 |

| BAMBI Picky Eating | 1.88 (0.55) | 1.98 (0.60) | 1.98 (0.59) | 1.62 | .20 |

Cross-lagged analysis results for the conceptual model depicted in Figure 1 are presented in Table 2. The fit of both cross-lagged models was good with the ppp value for each model well within the recommended 0.05 to 0.95 range. Weight-for-length z-score, maternal pressuring feeding, and picky eating (by either measure) tracked strongly across all 3 age points. There were several concurrent associations between pressuring feeding and picky eating at 21 and 33 months, using both measures of picky eating. There were no prospective associations between pressuring feeding and future WLZ; WLZ and future pressuring feeding; pressuring feeding and future picky eating; picky eating and future pressuring feeding; or picky eating and future WLZ.

Table 2.

Path coefficients for model shown in Figure 1 in total sample (n=222)

| Path | CEBQ-T Food Fussiness ppp=0.42 |

BAMBI Picky Eating ppp=0.22 |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| WLZ 21m →WLZ 27m | b1 | 0.847* | 0.846* |

| WLZ 27m→ WLZ 33m | b2 | 0.861* | 0.856* |

| Pressuring feeding 21m→ Pressuring feeding 27m | b3 | 0.677* | 0.674* |

| Pressuring feeding 27m→ Pressuring feeding 33m | b4 | 0.547* | 0.565* |

| Picky eating 21m→ Picky eating 27m | b5 | 0.614* | 0.569* |

| Picky eating 27m→ Picky eating 33m | b6 | 0.743* | 0.627* |

| WLZ 21m→Picky eating 21m | b7 | −0.124 | −0.042 |

| WLZ 27m→ Picky eating 27m | b8 | 0.043 | 0.064 |

| WLZ 33 m→ Picky eating 33m | b9 | −0.048 | −0.199 |

| WLZ 21m→Pressuring feeding 21m | b10 | 0.003 | 0.011 |

| WLZ 27m→ Pressuring feeding 27m | b11 | −0.019 | −0.032 |

| WLZ 33 mos→ Pressuring feeding 33m | b12 | −0.082 | −0.081 |

| Picky eating 21m→Pressuring feeding 21m | b13 | 0.230* | 0.326* |

| Picky eating 27m→ Pressuring feeding 27m | b14 | 0.009 | 0.181 |

| Picky eating 33 m→ Pressuring feeding 33m | b15 | 0.139 | 0.218* |

| Pressuring feeding 21m→WLZ 27m | b16 | −0.037 | 0.003 |

| Pressuring feeding 27m→ WLZ 33m | b17 | 0.037 | 0.028 |

| WLZ 21 m→ Pressuring feeding 27m | b18 | 0.016 | −0.018 |

| WLZ 27m→ Pressuring feeding 33m | b19 | −0.025 | −0.030 |

| Pressuring feeding 21m→Picky eating 27m | b20 | 0.089 | 0.040 |

| Pressuring feeding 27m→ Picky eating 33m | b21 | 0.094 | 0.089 |

| Picky eating 21m→Pressuring feeding 27m | b22 | 0.030 | 0.003 |

| Picky eating 27m→ Pressuring feeding 33m | b23 | 0.055 | −0.016 |

| WLZ 21m→Picky eating 27m | b24 | 0.033 | −0.027 |

| WLZ 27m→ Picky eating 33m | b25 | 0.029 | 0.023 |

| Picky eating 21m→ WLZ 27m | b26 | 0.016 | −0.066 |

| Picky eating 27m→ WLZ 33m | b27 | −0.080 | −0.055 |

p<.05; ppp= posterior predictive p-values, m=months

DISCUSSION

There were several main findings. First, child weight-for-length z-score, maternal self-report of pressuring her child to eat, and mother-reported child picky eating tracked across toddlerhood. Although there was evidence for concurrent associations between maternal report of pressuring feeding and maternal report of child picky eating, there was no evidence to support prospective associations between pressuring feeding and future WLZ; WLZ and future pressuring feeding; pressuring feeding and future picky eating; picky eating and future pressuring feeding; or picky eating and future WLZ.

Consistent with prior reports, pressuring feeding (Afonso et al., 2016; Faith et al., 2004; Gregory et al., 2010; Webber et al., 2010), picky eating (Gregory et al., 2010; Marchi & Cohen, 1990; Mascola, Bryson, & Agras, 2010), and WLZ (Nader et al., 2006) tracked within individuals across childhood. We found that mothers who self-reported using pressuring feeding practices also rated their children concurrently as pickier eaters, consistent with prior literature examining these associations concurrently (Carper et al., 2000; Carruth et al., 1998; Farrow et al., 2009; Ventura & Birch, 2008; Wardle et al., 2005). These studies used a range of measures of pressuring feeding and picky eating, with just one using CEBQ and IFSQ as we did (Farrow et al., 2009). The cohorts in prior studies were primarily white and middle income and all from the US or UK (Carper et al., 2000; Carruth et al., 1998; Farrow et al., 2009; Wardle et al., 2005), in contrast to our cohort which was entirely low-income and with greater racial/ethnic diversity. Prior cohorts had sample sizes similar to ours, ranging from fewer than 200 (Carper et al., 2000; Carruth et al., 1998; Farrow et al., 2009), to one study with 564 participants (Wardle et al., 2005). The ages of children in the prior studies were entirely between 2–6 years (Carper et al., 2000; Carruth et al., 1998; Farrow et al., 2009), and our cohort was therefore slightly younger. In summary, among cohorts from the US and UK, who are primarily white and middle-income in the preschool age range, mothers (and in one case the children themselves (Carper et al., 2000)) report across a range of measures the co-occurrence of maternal pressuring feeding and child picky eating. Our findings confirm and extend this observation to a slightly younger age range and slightly more racially and ethnically diverse cohort. Future research might consider examining this association in more diverse populations and at older ages.

We did not find concurrent associations between pressuring feeding and WLZ. These findings differ from the primarily inverse associations found in 11 of 13 cross-sectional studies among children ages 4 to 12 years in one recent review (Shloim et al., 2015). Our findings may have differed from those in this review given that the children in our cohort were younger. In other studies of toddlers, there have also been null concurrent associations between pressuring feeding and child WLZ (Blissett & Farrow, 2007; Lumeng et al., 2012). In addition, as described elsewhere (Lumeng et al., 2012), associations between pressuring feeding and WLZ are more likely to be null when the measures of pressuring feeding are less controlling or intrusive, as may have been the case in our study. A different measure of pressuring feeding that captured more assertive feeding practices may have found different associations with WLZ.

We found no evidence for a prospective relationship between pressuring feeding and future growth, consistent with all prior studies that have examined this question (Faith et al., 2004; Gregory et al., 2010; Lumeng et al., 2012; Webber et al., 2010). Specifically, a prior study in a relatively large US cohort that was primarily white and middle-income also found no prospective association between pressuring feeding at age 15 months and weight gain to 36 months (Lumeng et al., 2012). Among a primarily white cohort of 57 children, there was no cross-lagged correlation between pressuring feeding at age 5 years and body mass index at age 7 years (Myles S. Faith et al., 2004). Similarly, among a primarily white cohort of 2- to 4- year old children in Australia, there was no prospective association between pressuring feeding and body mass index one year later (Gregory et al., 2010). Likewise, among 7- to 9- year old children in the UK, there was no prospective association between pressuring feeding and child body mass index 3 years later (Webber et al., 2010). Our study replicates these null prospective findings in a relatively diverse cohort of low-income US toddlers. Overall, the pattern of results in our study as well as prior work suggests that pressuring feeding is unlikely to be a pathway to altering a child’s growth, particularly for low-income toddlers. Specifically, altering the growth trajectory of low-income toddlers (whether to reduce or increase that trajectory) may require other strategies besides addressing maternal pressuring feeding.

We also did not find concurrent associations between picky eating and WLZ, consistent with the primarily null associations in cross-sectional studies described in a recent review (Brown, Schaaf, Cohen, Irby, & Skelton, 2016). We also found no evidence to support the hypothesis that picky eating causes either increased or decreased rates of growth, using two different measures of picky eating, which is also consistent with the primarily null findings of longitudinal studies in a recent review (Brown et al., 2016).

Although parents are often cautioned against pressuring their children to eat on the premise that pressuring the child could further increase pickiness, we found no evidence to support a prospective relationship. This aligns with findings in a primarily white cohort of 156 2- to 4- year old children in Australia; pressuring feeding was not associated with greater food fussiness one year later when baseline food fussiness was controlled (Gregory et al., 2010). A prior study among 7 to 9 year old girls found a prospective association between pressuring and picky eating 2 years later (Galloway et al., 2005); however, this study did not control for baseline picky eating, which could explain the discrepancy with other studies. In addition, it is possible that pressuring feeding prospectively predicts increases in pickiness in school age, but not toddler and preschool-aged children. Overall, the research to date suggests that pressuring feeding in toddler- and preschool-aged children has little impact on changing picky eating, at least over a period of one year. Future studies in other age groups and over longer follow up periods may further clarify any potential association between pressuring feeding and picky eating.

Limitations

There are several limitations to this study. The longitudinal design is a strength, but due to the high-risk nature of the study cohort, attrition was high and there were missing data. Results may not be generalizable to other study populations outside low-income toddlers in the United States. There is debate in the field regarding how to best measure the construct of picky eating (Brown et al., 2016), and our measures included some variety of reluctance to eat both new foods (food neophobia) and familiar foods (picky eating). Despite these limitations, the study was able to test pathways in common theoretical frameworks in a very young age group longitudinally in a diverse population at a low socioeconomic level.

Conclusion

We found that maternal pressuring feeding, child picky eating, and weight-for-length z-score tracked over a year during early childhood. Although pressuring feeding and picky eating were concurrently associated, we found no prospective associations between pressuring feeding, child picky eating, and weight-for-length z-score.

There are several areas for future work. First, our measure of pressuring feeding has substantial overlap with how pressuring feeding is measured in a range of questionnaire measures, but compared to some other measures, did not focus as strongly on more intrusive pressuring feeding strategies (i.e., age inappropriate spoon feeding, bribery, punishment, etc). It is possible that findings may differ with alternative definitions of pressuring feeding, and this possibility should be explored. Secondly, the findings may differ among different subgroups, such as children with different weight status at baseline, or from different racial/ethnic or socioeconomic groups. Future work should test these associations in different subgroups. Third, future work should consider examining these associations in even younger age groups, during bottle feeding and the transition to solid foods, using longitudinal designs. Finally, additional studies that examine pressuring feeding, picky eating, and child growth longitudinally and employ cross-lagged analyses in large sample sizes with power to detect small but clinically significant effects will be important.

In summary, our results call into question the value of attempts to alter maternal pressuring feeding as a strategy to alter children’s picky eating or growth. Although parents are interested in how to reduce picky eating, and providers are enthusiastic about reducing parental pressure to eat, there is little evidence that intervening upon these behaviors impacts growth trajectories. Additional work is needed to identify effective strategies that target salient behaviors.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Sources of Support: R01HD069179

Abbreviations

- WLZ

weight-for-length z-score

APPENDIX

Pressure to Finish Subscale Items, IFSQ

-

2

It’s important that an infant finish all of the milk in his or her bottle

-

12

It’s very important that a toddler finish all the food that is on his or her plate

-

37

I try to get (name of child) to eat even if s/he seems not hungry

-

38

If (name of child) will not try a new food that I give him/her, I will work hard to have him/her try it during that meal

-

43

I praise (name of child) after each bite to encourage him/her to finish his/her food

-

45

I try to get (name of child) to finish his/her food

-

47

If (name of child) seems full, I encourage him/her to finish his/her food anyway

-

51

I try to get (name of child) to finish his/her milk

Food Fussiness Subscale Items from CEBQ-T

-

8

My child refuses new foods at first.

-

15

My child enjoys a wide variety of foods REVERSED.

-

20

My child enjoys tasting new food REVERSED.

-

24

My child is difficult to please with meals.

-

25

My child decides that s/he doesn’t like food even without tasting it.

-

29

My child is interested in tasting food s/he hasn’t tasted before REVERSED.

Food Refusal and Limited Variety Items from BAMBI

-

1

My child cries or screams during mealtimes

-

2

My child turns his/her face or body away from food

-

4

My child expels (spits out) food that he/she has eaten

-

7

My child is disruptive during mealtimes (pushing/throwing utensils, food)

-

8

My child closes his/her mouth tightly when food is presented

-

10

My child is willing to try new foods- REVERSED

-

11

My child dislikes certain foods and won’t eat them

-

13

My child prefers the same foods at each meal

-

14

My child prefers crunchy foods (e.g. snacks, crackers)

-

15

My child accepts or prefers a variety of foods- REVERSED

-

16

My child prefers to have food served in a particular way

-

17

My child prefers only sweet foods (e.g. candy, sugary cereals)

-

18

My child prefers food prepared in a particular way (e.g. fried foods, cold cereals, raw vegetables)

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Author Contributions: JCL, KR, and ALM designed research; JCL, KR and ALM conducted research; DA and NK analyzed data; JCL wrote the paper; JCL had primary responsibility for final content. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- Afonso L, Lopes C, Severo M, Santos S, Real H, Durão C, Oliveira A. Bidirectional association between parental child-feeding practices and body mass index at 4 and 7 y of age. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 2016;103(3):861–867. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.115.120824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barlow SE The Expert Committee. Expert Committee Recommendations Regarding the Prevention, Assessment, and Treatment of Child and Adolescent Overweight and Obesity: Summary Report. Pediatrics. 2007;120(Supplement 4):S164–S192. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-2329C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blissett J, Farrow C. Predictors of maternal control of feeding at 1 and 2 years of age. Int J Obes. 2007;31(10):1520–1526. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0803661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown CL, Schaaf EBV, Cohen GM, Irby MB, Skelton JA. Association of Picky Eating and Food Neophobia with Weight: A Systematic Review. Childhood Obesity. 2016 doi: 10.1089/chi.2015.0189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cardona Cano S, Tiemeier H, Van Hoeken D, Tharner A, Jaddoe VW, Hofman A, Hoek HW. Trajectories of picky eating during childhood: A general population study. Int J Eat Disord. 2015;48(6):570–579. doi: 10.1002/eat.22384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carnell S, Wardle J. Measuring behavioural susceptibility to obesity: validation of the child eating behaviour questionnaire. Appetite. 2007;48(1):104–113. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2006.07.075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carper JL, Orlet Fisher J, Birch LL. Young girls' emerging dietary restraint and disinhibition are related to parental control in child feeding. Appetite. 2000;35(2):121–129. doi: 10.1006/appe.2000.0343. doi: https://doi.org/10.1006/appe.2000.0343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carruth BR, Skinner J, Houck K, Moran J, Coletta F, III, Ott D. The phenomenon of “picky eater”: A behavioral marker in eating patterns of toddlers. Journal of the American College of Nutrition. 1998;17(2):180–186. doi: 10.1080/07315724.1998.10718744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark HR, Goyder E, Bissell P, Blank L, Peters J. How do parents' child-feeding behaviours influence child weight? Implications for childhood obesity policy. Journal of public health (Oxford, England) 2007;29(2):132–141. doi: 10.1093/pubmed/fdm012. doi:fdm012 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dovey TM, Staples PA, Gibson EL, Halford JCG. Food neophobia and ‘picky/fussy’ eating in children: A review. Appetite. 2008;50(2–3):181–193. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2007.09.009. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2007.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubois L, Farmer A, Girard M, Peterson K, Tatone-Tokuda F. Problem eating behaviors related to social factors and body weight in preschool children: A longitudinal study. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity. 2007;4(1):9. doi: 10.1186/1479-5868-4-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faith MS, Berkowitz RI, Stallings VA, Kerns J, Storey M, Stunkard AJ. Parental feeding attitudes and styles and child body mass index: Prospective analysis of a gene-environment interaction. Pediatrics. 2004;114(4):e429–e436. doi: 10.1542/peds.2003-1075-L. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faith MS, Berkowitz RI, Stallings VA, Kerns J, Storey M, Stunkard AJ. Parental feeding attitudes and styles and child body mass index: prospective analysis of a gene-environment interaction. Pediatrics. 2004;114(4):e429–436. doi: 10.1542/peds.2003-1075-L. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farrow CV, Galloway AT, Fraser K. Sibling eating behaviours and differential child feeding practices reported by parents. Appetite. 2009;52(2):307–312. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2008.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finistrella V, Manco M, Ferrara A, Rustico C, Presaghi F, Morino G. Cross-Sectional Exploration of Maternal Reports of Food Neophobia and Pickiness in Preschooler-Mother Dyads. Journal of the American College of Nutrition. 2012;31(3):152–159. doi: 10.1080/07315724.2012.10720022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galloway AT, Fiorito L, Lee Y, Birch LL. Parental pressure, dietary patterns, and weight status among girls who are "picky eaters". J Am Diet Assoc. 2005;105(4):541–548. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2005.01.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galloway AT, Fiorito L, Lee Y, Birch LL. Parental pressure, dietary patterns, and weight status among girls who are “picky eaters”. Journal of the American Dietetic Association. 2005;105(4):541–548. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2005.01.029. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jada.2005.01.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gelman A. Bayesian data analysis. Boca Raton, Fla: Chapman & Hall/CRC; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Gibson EL, Kreichauf S, Wildgruber A, Vögele C, Summerbell CD, Nixon C, ToyBox-Study G. A narrative review of psychological and educational strategies applied to young children's eating behaviours aimed at reducing obesity risk. Obesity Reviews. 2012;13:85–95. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2011.00939.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gregory J, Paxton S, Brozovic A. Maternal feeding practices, child eating behaviour, and body mass index in preschool-aged children: a prospective analysis. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity. 2010;7(55):1–10. doi: 10.1186/1479-5868-7-55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hafstad GS, Abebe DS, Torgersen L, von Soest T. Picky eating in preschool children: the predictive role of the child's temperament and mother's negative affectivity. Eat Behav. 2013;14(3):274–277. doi: 10.1016/j.eatbeh.2013.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hassink SG. Picky Eaters. A Parent's Guide to Childhood Obesity: A Road Map to Health. 2006 11/21/2015. Retrieved from https://www.healthychildren.org/English/ages-stages/toddler/nutrition/Pages/Picky-Eaters.aspx.

- Hayes JF, Altman M, Kolko RP, Balantekin KN, Holland JC, Stein RI, Schechtman KB. Decreasing food fussiness in children with obesity leads to greater weight loss in family based treatment. Obesity, Epub ahead of print. 2016 doi: 10.1002/oby.21622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jansen PW, Tharner A, van der Ende J, Wake M, Raat H, Hofman A, Tiemeier H. Feeding practices and child weight: is the association bidirectional in preschool children? American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 2014;100(5):1329–1336. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.114.088922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lukens CT, Linscheid TR. Development and validation of an inventory to assess mealtime behavior problems in children with autism. Journal of autism and developmental disorders. 2008;38(2):342–352. doi: 10.1007/s10803-007-0401-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lumeng JC, Ozbeki TN, Appugliese DP, Kaciroti N, Corwyn RF, Bradley RH. Observed assertive and intrusive maternal feeding behaviors increase child adiposity. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 2012;95(3):640–647. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.111.024851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marchi M, Cohen P. Early childhood eating behaviors and adolescent eating disorders. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 1990;29(1):112–117. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199001000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mascola AJ, Bryson SW, Agras WS. Picky eating during childhood: A longitudinal study to age 11 years. Eating Behaviors. 2010;11(4):253–257. doi: 10.1016/j.eatbeh.2010.05.006. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eatbeh.2010.05.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nader PR, O'Brien M, Houts R, Bradley R, Belsky J, Crosnoe R, Susman EJ. Identifying risk for obesity in early childhood. Pediatrics. 2006;118(3):e594–601. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-2801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nowicka P, Sorjonen K, Pietrobelli A, Flodmark CE, Faith MS. Parental feeding practices and associations with child weight status. Swedish validation of the Child Feeding Questionnaire finds parents of 4-year-olds less restrictive. Appetite. 2014;81:232–241. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2014.06.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogden CL, Lamb MM, Carroll MD, Flegal KM. Obesity and Socioeconomic Status in Children and Adolescents: United States, 2005–2008. NCHS Data Brief. Number 51. National Center for Health Statistics. 2010 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodgers RF, Paxton SJ, Massey R, Campbell KJ, Wertheim EH, Skouteris H, Gibbons K. Maternal feeding practices predict weight gain and obesogenic eating behaviors in young children: a prospective study. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity. 2013;10(1):1–10. doi: 10.1186/1479-5868-10-24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shloim N, Edelson LR, Martin N, Hetherington MM. Parenting styles, feeding styles, feeding practices, and weight status in 4–12 year-old children: a systematic review of the literature. Frontiers in psychology. 2015;6:1849. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2015.01849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tharner A, Jansen PW, Kiefte-de Jong JC, Moll HA, van der Ende J, Jaddoe VW, Franco OH. Toward an operative diagnosis of fussy/picky eating: a latent profile approach in a population-based cohort. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity. 2014;11(1):14. doi: 10.1186/1479-5868-11-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson AL, Adair LS, Bentley ME. Pressuring and restrictive feeding styles influence infant feeding and size among a low-income African-American sample. Obesity. 2013;21(3):562–571. doi: 10.1002/oby.20091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson AL, Mendez MA, Borja JB, Adair LS, Zimmer CR, Bentley ME. Development and validation of the infant feeding style questionnaire. Appetite. 2009;53(2):210–221. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2009.06.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tschann JM, Martinez SM, Penilla C, Gregorich SE, Pasch LA, de Groat CL, Butte NF. Parental feeding practices and child weight status in Mexican American families: a longitudinal analysis. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity. 2015;12(1):1–10. doi: 10.1186/s12966-015-0224-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ventura AK, Birch LL. Does parenting affect children's eating and weight status? International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity. 2008;5(1):15. doi: 10.1186/1479-5868-5-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wardle J, Carnell S, Cooke L. Parental control over feeding and children's fruit and vegetable intake: How are they related? Journal of the American Dietetic Association. 2005;105(2):227–232. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2004.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Webber L, Cooke L, Hill C, Wardle J. Child adiposity and maternal feeding practices a longitudinal analysis. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 2010;92(6):1423–1428. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.2010.30112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.