Abstract

The aim of this study was to identify the brain networks from early-phase 11C-PIB (perfusion PIB, pPIB) data and to compare the brain networks of patients with differentiating Alzheimer's disease (AD) with cognitively normal subjects (CN) and of mild cognitively impaired patients (MCI) with CN. Forty participants (14 CN, 12 MCI, and 14 AD) underwent 11C-PIB and 18F-FDG PET/CT scans. Parallel independent component analysis (pICA) was used to identify correlated brain networks from the 11C-pPIB and 18F-FDG data, and a two-sample t-test was used to evaluate group differences in the corrected brain networks between AD and CN, and between MCI and CN. Our study identified a brain network of perfusion (early-phase 11C-PIB) that highly correlated with a glucose metabolism (18F-FDG) brain network and colocalized with the default mode network (DMN) in an AD-specific neurodegenerative cohort. Particularly, decreased 18F-FDG uptake correlated with a decreased regional cerebral blood flow in the frontal, parietal, and temporal regions of the DMN. The group comparisons revealed similar spatial patterns of the brain networks derived from the 11C-pPIB and 18F-FDG data. Our findings indicate that 11C-pPIB derived from the early-phase 11C-PIB could provide complementary information for 18F-FDG examination in AD.

1. Introduction

The current diagnostic criteria for Alzheimer's disease (AD) include amyloid-β (Aβ) and fludeoxyglucose F 18 (18F-FDG) positron emission tomography (PET) imaging biomarkers that provide amyloid burden and neuronal injury information [1]. Under both physiological and pathological conditions, the cerebral blood flow is coupled to cerebral metabolic rates of glucose measured by FDG-PET [2, 3]. Several studies have reported that perfusion data estimated from early-phase (11C)-labeled Pittsburgh Compound B (11C-PIB), referred to as perfusion PIB (11C-pPIB), correlated with glucose metabolism as estimated by 18F-FDG [4–6]. Moreover, recent PET studies using amyloid and Tau tracers indicated that early-phase images of PET tracers provided information on brain perfusion, closely related to glucose metabolism, and could be used as a neurofunctional biomarker [7–9]. Previous studies mostly focused on regions of interest or on whole brain voxel wise measurements [5, 6, 10], which are not equipped to capture distributed variations in cross-brain networks. It remains unclear how early-phase PIB-PET and glucose metabolism correlate with each other and how such a relationship varies with disease progression at the brain network level.

Nowadays, multivariate statistical paradigms (e.g., principal component analysis [PCA] or independent component analysis [ICA]), which assess distributed variations and their interrelationships in multiple neuroimaging data, provide a better framework for the integrative analysis of multimodal imaging data. As a data-driven analytic method, ICA is a powerful tool to investigate brain networks based on neuroimaging data. This data can be collected with, including functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) [11], magnetoencephalography [12], electroencephalography [13, 14], and structural MRI [15] and PET imaging [16]. Parallel independent component analysis (pICA) [17] is a variation of ICA that allows one to estimate independent components as well as multimodal patterns or mixed coefficients. pICA has recently been used to study the mechanisms by which Aβ deposition leads to neurodegeneration and cognitive decline [18]. It was also used to study the spatial patterns of Aβ deposition and glucose metabolism across an AD population [19]. Moreover, pICA has been used successfully to reveal the complex relationship between different PET elements of AD pathophysiology [19]. pICA, therefore, promises to be a suitable means of exploring the spatial patterns of regional cerebral blood flow (rCBF), evaluated by pPIB, and glucose metabolism at the level of the whole brain network.

In the present study, we adopted pICA to derive brain networks from early-phase of 11C-PIB and 18F-FDG to explore their relationships across AD, mild cognitive impairment (MCI), and cognitively normal (CN) patient groups. This study was designed to (1) identify whether distinctive functional connectivity networks, such as the default mode network (DMN), can be detected from early-phase 11C-PIB data and (2) to explore the discriminability of the network derived from 11C-pPIB for distinguishing AD/MCI from CN.

2. Results

2.1. Patient Characteristics

As described in our previous study [10], patients in the MCI groups (F = 4.23, p = 0.02) were older than in the CN and AD groups, and there was no significant difference in gender or the level of education for the two groups (p = 0.13 and 0.52, resp.). Cognitive performance, estimated from Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR) and Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) tests, was significantly worse in AD patients than MCI and CN participants (F = 65.93, p < 0.001). However, no significant difference in MMSE test results was observed between the MCI and CN groups (Table 1). Furthermore, the amyloid status of all participants is shown in Table 1; the cerebellar gray matter was used as the reference region and the standard uptake value ratio (SUVR) cutoff value was set to 1.15 [20, 21].

Table 1.

Demographic, clinical, and neuropsychological characteristics of the patients.

| AD (n = 14) | MCI (n = 12) | CN (n = 14) | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex (male/female) | 4/10 | 8/4 | 5/9 | 0.13 |

| Age (years) | 68.1 ± 9.9 | 75.8 ± 8.6 | 67.4 ± 5.0 | 0.02∗ |

| Education (years) | 11.6 ± 3.9 | 13.3 ± 3.8 | 11.9 ± 4.1 | 0.52 |

| Amyloid status (PIB +/−) | 12/2 | 9/3 | 1/13 | <0.001∗ |

| MMSE | 19.4 ± 3.3 | 27.3 ± 1.6 | 28.4 ± 1.2 | <0.001∗ |

| CDR | 0.96 ± 0.13 | 0.5 | 0 | <0.001∗ |

With the cerebellar cortex as the reference region, voxel wise semiquantitative calculations of global standardized uptake value ratios (SUVR) for all subjects were performed. The amyloid status was reflected by the Pittsburgh Compound B (PIB) burden and the cutoff value of SUVR was set to 1.15 to determine PIB positive or negative. Chi-square was used for the gender comparison; one-way ANOVA with a Bonferroni post hoc test was used for age and neuropsychological test comparisons. ∗p< 0.05. AD: Alzheimer's disease; MCI: mild cognitively impaired; CN: cognitively normal; MMSE: Mini-Mental State Examination; CDR: Clinical Dementia Rating.

2.2. Correlated 11C-pPIB and 18F-FDG Networks

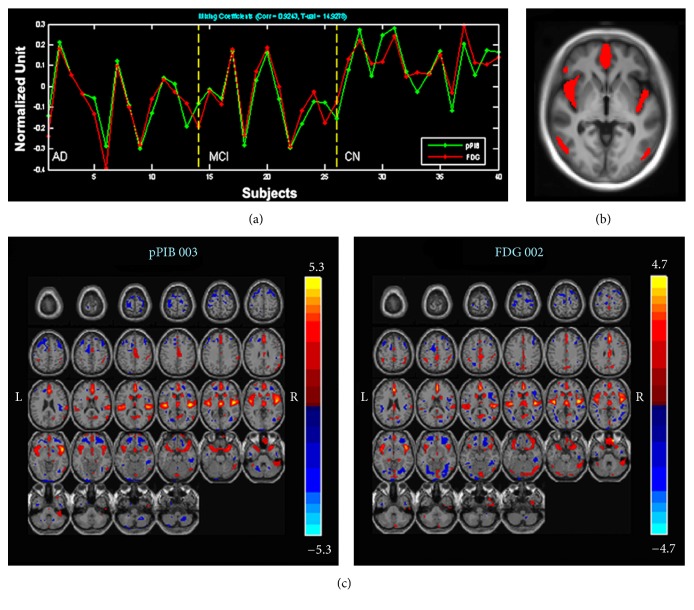

One pair of components (networks) was identified. It had the highest correlation (R = 0.92) between the 18F-FDG and 11C-pPIB data and was largely colocalized with the DMN [22, 23]. As listed in Table 2, the highest correlated component pair also differed significantly between AD/MCI and CN in their loading coefficients. This pair of components showed that a decrease in 18F-FDG uptake correlated with a decrease in perfusion in the frontal, parietal, and temporal regions, including the medial frontal gyrus (MFG), anterior cingulate cortex (ACC), posterior cingulate cortex (PCC)/precuneus, superior temporal gyrus (STG), temporal pole, and orbitofrontal gyrus (Figure 1).

Table 2.

Two sample t-test results of the highest correlated component pair of 11C-pPIB and 18F-18F-FDG between AD and CN and between MCI and CN groups.

| AD versus CN | MCI versus CN | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 11C-pPIB | 18F-FDG | 11C-pPIB | 18F-FDG | ||||

| pvalue | T value | pvalue | T value | pvalue | T value | p value | T value |

| 0.0010 | −3.6907 | 0.0002 | −4.3774 | 0.0009 | −3.7993 | 0.0010 | −3.7279 |

AD: Alzheimer's disease; MCI: mild cognitively impaired; CN: cognitively normal; 11C-pPIB: (11C)-labeled Pittsburgh Compound B; 18F-FDG: fludeoxyglucose F 18.

Figure 1.

Correlated components of 11C-pPIB and 18F-FDG. (a) Loading parameters with a significant correlation in all participants with 18F-FDG (red) and 11C-pPIB (green). (b) Common regions of the correlated 18F-FDG and 11C-pPIB components, including bilateral medial frontal gyrus, temporal lobe, and right insular lobe. (c) Correlated components of 11C-pPIB (left) and 18F-FDG (right), including the medial frontal gyrus, anterior cingulate cortex, posterior cingulate cortex/precuneus, superior temporal gyrus, temporal pole, and orbitofrontal gyrus. 11C-pPIB, (11C)-labeled Pittsburgh Compound B; 18F-FDG, fludeoxyglucose F 18.

2.3. Group Comparisons of 18F-FDG and 11C-pPIB within the Correlated Network

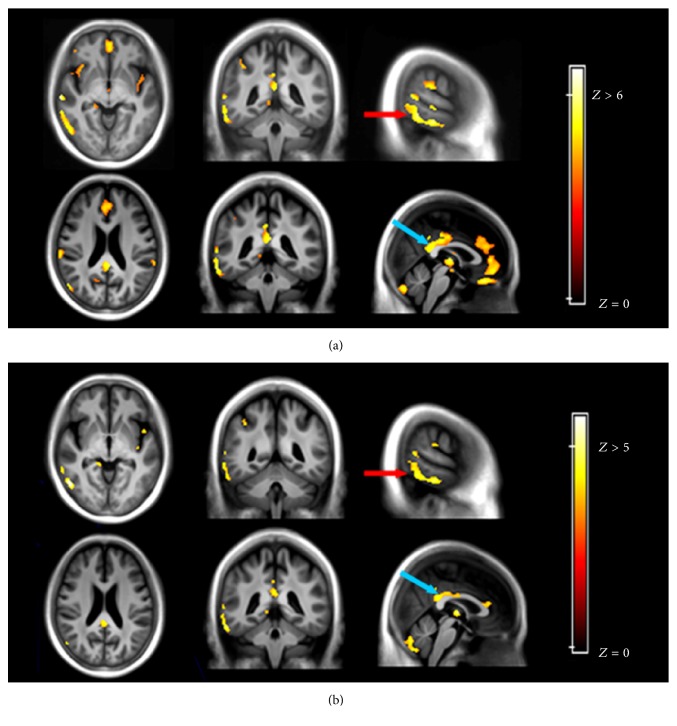

Tables 3 and 4 summarize the group differences within the correlated networks in 18F-FDG and 11C-pPIB measurements between AD and CN groups (Figure 2). Despite fewer regions detected by 11C-pPIB than 18F-FDG in the intergroup comparisons, similar patterns were observed. The hypometabolic regions largely colocalized with the hypoperfusion areas, including the STG, Limbic lobe/ParaHippo, superior parietal lobe (SPL), PCC, and ACC.

Table 3.

18F-FDG–revealed hypometabolic brain areas differentiating AD and CN groups.

| Brain region | Voxel-level | X | Y | Z | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T | Z | p uncorrected | ||||

| Limbic lobe/R ParaHippo | 6.75 | 5.05 | 0.000 | 22 | −4 | −38 |

| 4.78 | 3.99 | 0.000 | 22 | 6 | −24 | |

| R STG/BA39 | 6.40 | 4.88 | 0.000 | 58 | −58 | 26 |

| 5.18 | 4.23 | 0.000 | 54 | −54 | 44 | |

| R MTG/ ITG | 5.99 | 4.68 | 0.000 | 54 | −64 | 18 |

| 5.85 | 4.60 | 0.000 | 66 | −40 | −14 | |

| Rectal gyrus | 5.89 | 4.62 | 0.000 | 8 | 32 | −26 |

| Limbic lobe/L ParaHippo | 5.79 | 4.57 | 0.000 | −22 | 4 | −22 |

| PCC/BA29 | 5.64 | 4.49 | 0.000 | −2 | −42 | 20 |

| 5.51 | 4.41 | 0.000 | 0 | −26 | 32 | |

| R MFG/ACC | 5.09 | 4.18 | 0.000 | 2 | 50 | −12 |

| 4.88 | 4.05 | 0.000 | 4 | 38 | 24 | |

| R SPL/BA7 | 5.01 | 4.13 | 0.000 | 36 | −58 | 54 |

| 4.70 | 3.94 | 0.000 | 40 | −48 | 50 | |

| L STG/BA13 | 4.95 | 4.10 | 0.000 | −50 | −4 | 0 |

| 4.42 | 3.76 | 0.000 | −46 | 6 | −2 | |

| L STG/BA42/Insula | 4.79 | 4.00 | 0.000 | −64 | −36 | 18 |

| 3.82 | 3.36 | 0.000 | −54 | −32 | 18 | |

| L STG/BA38 | 4.73 | 3.96 | 0.000 | 26 | 6 | −48 |

| L IFG/BA47 | 4.70 | 3.94 | 0.000 | −40 | 24 | −16 |

| 4.09 | 3.55 | 0.000 | −38 | 14 | −12 | |

Threshold: T = 3.45, p = 0.001; Extent threshold: k = 50 voxel, voxel size: [2.0,2.0,2.0] mm. 18F-FDG: fludeoxyglucose F 18; AD: Alzheimer's disease; CN: cognitively normal; STG: superior temporal gyrus; BA: Brodmann area; MTG: middle temporal gyrus; ITG: inferior temporal cortex; PCC: posterior cingulate cortex; MFG: medial frontal gyrus; ACC: anterior cingulate cortex; SPL: superior parietal lobe; IFG: inferior frontal gyrus.

Table 4.

11C-pPIB–revealed hypoperfusion brain areas differentiating AD and CN groups.

| Brain region | Voxel-level | X | Y | Z | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T | Z | p uncorrected | ||||

| R ITG/BA19 | 5.66 | 4.50 | 0.000 | 54 | −64 | −6 |

| 5.32 | 4.31 | 0.000 | 54 | −66 | 14 | |

| L STG/BA22 | 5.00 | 4.13 | 0.000 | 66 | −46 | 6 |

| Limbic lobe/L ParaHippo | 4.74 | 3.97 | 0.000 | −22 | 4 | −22 |

| BA23/PCC | 4.41 | 3.76 | 0.000 | 2 | −38 | 24 |

| 4.15 | 3.59 | 0.000 | −2 | −26 | 30 | |

| Insula/BA13 | 4.39 | 3.74 | 0.000 | 42 | −20 | 12 |

| R STG/BA39 | 4.37 | 3.73 | 0.000 | 58 | −56 | 26 |

| L STG/BA22 | 4.18 | 3.60 | 0.000 | −52 | 0 | 0 |

| R ITG/BA20 | 3.89 | 3.41 | 0.000 | 58 | −8 | −34 |

| ACC/BA24 | 3.86 | 3.38 | 0.000 | 2 | 32 | 16 |

| Limbic lobe/R ParaHippo | 3.84 | 3.38 | 0.000 | 14 | −38 | −2 |

| R SPL/BA7 | 3.82 | 3.35 | 0.000 | 36 | −58 | 54 |

| R IPL/BA40 | 3.81 | 3.32 | 0.000 | 40 | −48 | 44 |

Threshold: T = 3.45, p = 0.001; Extent threshold: k = 50 voxel, Voxel size: [2.0,2.0,2.0] mm. 11C-pPIB: (11C)-labeled Pittsburgh Compound B; AD: Alzheimer's disease; CN: cognitively normal; ITG: inferior temporal cortex; STG: superior temporal gyrus; BA: Brodmann area; ACC: anterior cingulate cortex; SPL: superior parietal lobe; IPL: inferior parietal lobule.

Figure 2.

Comparison of 18F-FDG (a) and 11C-pPIB (b) between Alzheimer's disease (AD) and cognitively normal (CN) groups. Images show a similar decrease in the radioactive pattern, such as for the right superior temporal gyrus (red arrow, x = −50, y = −4, z = 5) and posterior cingulate cortex (blue arrow, x = 2, y = −41, z = 23). 11C-pPIB, (11C)-labeled Pittsburgh Compound B; 18F-FDG, fludeoxyglucose F 18.

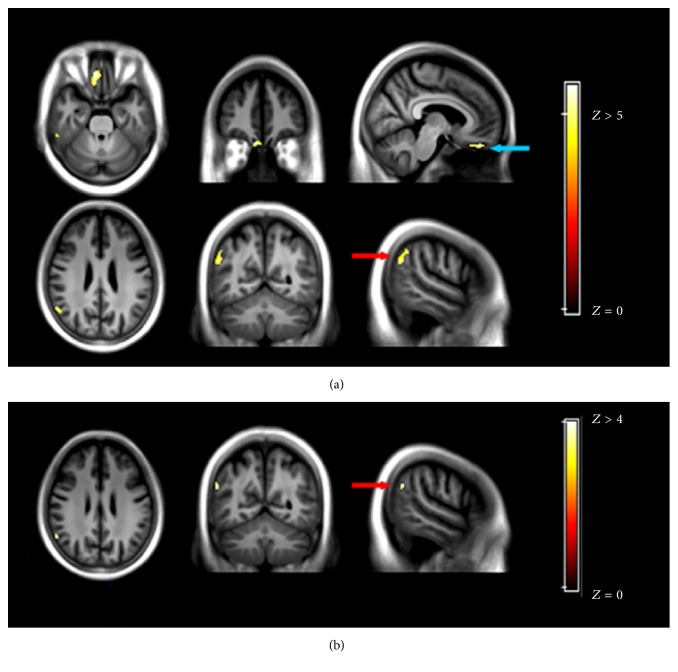

The comparison between MCI and CN patients within the correlated network revealed that the 18F-FDG uptake was less in the rectal gyrus/Brodmann area 11 (BA11), BA40, left PCC, BA20, and inferior parietal lobule (IPL)/STG (Figure 3). In contrast, hypoperfusion was only detected in the IPL.

Figure 3.

Comparison of 18F-FDG (a) and 11C-pPIB (b) between mild cognitive impairment (MCI) and cognitively normal (CN) groups. (a) 18F-FDG images showing hypometabolic regions in the rectal gyrus (blue arrow, x = 8, y = 42, z = −26) and inferior parietal lobule (red arrow, x = 54, y = −52, z = 50) and (b) 11C-pPIB, showing only hypoperfusion in the inferior parietal lobule (red arrow, x = 58, y = −56, z = 46). 11C-pPIB, (11C)-labeled Pittsburgh Compound B; 18F-FDG, fludeoxyglucose F 18.

No statistically significant differences were observed in 18F-FDG or pPIB data for AD and MCI patients.

3. Discussion

In contrast to earlier studies looking into the dual-features of dynamic PIB-PET and the similarities between 11C-pPIB and 18F-FDG images [4–6, 10, 24, 25], the present study identified functional brain networks from early-phase 11C-PIB data. We first used pICA to identify the brain networks from the 11C-pPIB-PET imaging data and then explored the discriminability of the brain networks in diagnostic group differences. Concomitantly we were able to evaluate the use of 11C-pPIB as a neurofunctional biomarker for AD.

3.1. Highly Correlated Networks of 11C-pPIB and 18F-FDG

It is well-documented that there are changes in the brain structure, function, and cognition in AD patients associated with changes in brain networks [26–29]. Using resting state functional connectivity MRI (rs-fMRI), both intra- and internetwork correlations have already been detected in AD patients. These mainly involved DMN, dorsal attention, salience, control, and sensory-motor networks [29, 30]. Although AD is associated with widespread disruption of functional connectivity, the DMN is generally affected the most. Specifically, a declined functional connectivity and hypometabolism were observed consistently using various methodologies [27–29]. In the present study, highly correlated brain networks of 11C-pPIB and 18F-FDG data were identified using pICA. The correlated networks of 18F-FDG and 11C-pPIB covered the MFG, ACC, PCC/precuneus, STG, temporal pole, and orbitofrontal gyrus and largely colocalized with the DMN [22, 23]. The DMN regions are active at rest (hence the term “default”) [22] but are less active during demanding cognitive tasks. Under physiological conditions, up to 80% of the entire energy consumption by the brain at rest is spent on glutamate cycling, a biochemical process that can be observed by FDG-PET [31, 32]. In fact, the DMN is roughly divided into three major subdivisions, each with its own functional property: the ventral medial prefrontal cortex (supports emotional processing); the dorsal medial prefrontal cortex (self-referential mental activity); and the posterior cingulate cortex and adjacent precuneus plus the lateral parietal cortex (the recollection of prior experiences). These functional properties of DMN can be affected during task performance and also by various diseases [33]. For example, the episodic memory, requiring functional connectivity within the DMN [34, 35], is impaired in the early stages of AD. The abnormalities of DMN functional connectivity worsen with disease progression and are believed to explain the hypometabolism found in PET studies [36–39]. Moreover, FDG-PET measures both the CBF and the neuronal and synaptic activity [40]. A decrease in CBF is, furthermore, an indirect indicator of impairment caused by a decrease in the demand for blood. Nevertheless, the highly colocalized brain networks between glucose metabolism/rCBF and functional connectivity at rest indicated that glucose consumption and changes in rCBF are coupled and underpinning the neural activity. It is therefore argued that 11C-pPIB can be used in the future as a neurofunctional biomarker for neuroscience research.

3.2. Group Comparison of 11C-pPIB and 18F-FDG Measurements in Correlated Brain Networks

The second goal of this study was to evaluate whether the brain networks derived from 11C-pPIB data could differentiate AD/MCI patient groups from CN groups. Consistent with previous reports, AD patients were characteristically hypometabolic in the medial temporal lobe, STG, ACC, PCC/precuneus, SPL, and lateral temporoparietal cortex [36, 39]. 11C-pPIB also revealed significant intergroup differences, with regions of hypoperfusion in the STG, inferior temporal gyrus, SPL, and PCC, which is consistent with previous studies using 99mTechnetium-single photon emission computed tomography showing specific patterns of hypoperfusion in parietal-temporal cortical areas [41, 42]. The comparison between MCI and CN patients revealed hypometabolism in the rectal gyrus/BA11, IPL, left PCC, BA20, and IPL/STG, but only the IPL was detected by 11C-pPIB. The most reliable, early changes in metabolism are believed to be seen in the PCC [24, 36]. In fact, the IPL is an important region of the DMN and has a close functional connection with the PCC/precuneus [43, 44]. Esposito et al. reported that MCI patients who convert to AD showed increased connectivity in the right IPL, suggesting that this region plays an active role in the AD process [45]. Arguably, the hypometabolism and hyperperfusion that was detected in the IPL in this study was indicative of early neurodegeneration in AD. No significant difference was detected by either 18F-FDG or 11C-pPIB when comparing AD and MCI groups in the current study. We support our observations as follows. Firstly, the AD patients enrolled in the study who received the dual-tracer PET scan had slight to mild dementia. In addition, despite the amnestic type of the recruited MCI patients, MCI is still a heterogeneous syndrome and subject to various pathological substrates and clinical progress [46]. Therefore, the 18F-FDG and 11C-pPIB data may not detect a difference between AD and MCI due to the differences in clinical symptom severity and the heterogeneity in MCI. Secondly, the MCI patients were significantly older than the AD patients. Although age was regressed in the data analysis and no obvious vascular diseases were found on MR images of all subjects, the CBF will be affected by atherosclerosis, which usually progresses with aging. Thus, both patient's age and its possibly associated reduced CBF may have obscured our results. As discussed, the brain network of 11C-pPIB was found highly colocalized with DMN in AD pathology in this study. It is argued that disease-specific alternations of the brain networks can be detected by 11C-pPIB corresponding to distinctive pathophysiological processes, which merits further studies.

One limitation of the present study is the relatively small sample size. More recruits would give a larger dataset, which might help to identify the fine-grained brain networks underpinning 11C-pPIB and 18F-FDG. Furthermore, only the typical AD and amnestic MCI patients were enrolled in the current study and their disrupted brain networks mainly involved the DMN [27, 28, 47]. However, AD patients with atypical symptoms, such as Logopenic primary progressive aphasia and posterior cortical atrophy, had language and visual brain network dysfunctions matching their clinical symptoms [19, 47]. 11C-pPIB might, therefore, be used to validate the syndrome-specific alterations of the brain network in these clinical variants of AD. In addition, the present study did not investigate the functional networks derived from rs-fMRI data of the same cohort. Therefore, it is impossible to directly correlate the networks of 11C-pPIB and 18F-FDG with the functional networks in rs-fMRI data.

4. Conclusions

Here, we explored the 11C-pPIB spatial distribution pattern in AD, MCI, and CN patients. The pICA results revealed that the hypoperfusion pattern detected by 11C-pPIB was in agreement with the hypometabolism reflected by 18F-FDG, both of which were colocalized with the DMN. These results validated that 11C-pPIB could be a reliable biomarker of neural function and provide complementary information for 18F-FDG examination in AD.

5. Materials and Methods

5.1. Eligibility and Study Design

The study cohort was the same as in our previous studies [10, 25] and included 14 AD, 12 MCI, and 14 CN patients. The study was approved by the institutional review board of the Chinese PLA General Hospital. The study was compliant with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. All participants, or their appropriate representatives, signed informed consent forms after receiving a comprehensive written and verbal description of the study.

5.2. PET/CT Imaging

All patients underwent 11C-PIB and 18F-FDG scanning in a random order within two weeks. PET/CT scanning was performed using a Biograph Truepoint 64 (Siemens Healthcare, Germany) consisting of a PET scanner and a multislice CT. A vacuum cushion was used to restrict the participant's head to minimize movement during the scanning.

11C-PIB was synthesized from its corresponding precursors as described elsewhere [48]. In brief, 11C-PIB was synthesized by bubbling the 11CH3-Triflate through an acetone solution of 6-OH-BTA-0. It was then purified by semipreparative HPLC and reformulated with a radiochemical purity of >95% and a specific activity of 50 GBqµmol−1 (1.48 Ciµmol−1). The protocol for 11C-PIB scanning included an initial CT acquisition with intravenous tracer injection, followed by an immediate dynamic PET scan. A spiral CT for the brain was acquired with CT parameters of 120 kV, 100 mA, and slice thickness 3.75 mm, equal to that of PET. Then, a dynamic PET emission scan in 3D acquisition mode was started simultaneously with a single intravenous bolus of 11C-PIB at 4.81–5.55 MBq (0.13–0.15 mCi) kg−1. Dynamic brain PET images were collected continuously for 60 min, and the data were binned into 26 frames (1 × 10 sec, 6 × 5 sec, 4 × 20 sec, 2 × 1 min, 3 × 2 min, and 10 × 5 min).

18F-FDG-PET/CT scans were obtained 50 min after an intravenous injection of 18F-FDG at 4.81 to 5.55 MBq (0.13–0.15 mCi) kg−1. All participants were instructed to fast for 4 to 6 h. The blood glucose levels were also measured before injection to ensure that the levels were within the reference range. A 5-min frame was collected in 3D acquisition mode. Data obtained from the CT scans were used to correct the attenuation for PET emission data.

5.3. MR Structural Imaging

All participants underwent structural MRI with a 3.0-T GE scanner (Signa HD, WI, USA) and a standard GE quadrature head coil. The MRI and PET/CT examinations were performed within one week. The scan protocol included a high-resolution 3D T1-weighted spoiled gradient recalled echo sequence (TR = 7.0 ms, TE = 2.9 ms, Inversion time = 450 ms, thickness = 1.2 mm, matrix = 256 × 256, FOV = 240 mm, and in plane resolution = 0.9 × 0.9 mm2) to produce contiguous sagittal anatomic images for subsequent spatial normalization and coregistration.

The preprocessing of MRI and PET imaging is detailed elsewhere [10]. Specifically, all structural MRI images were segmented into gray matter, white matter, and cerebrospinal fluid and then used to construct a population template using DARTEL of SPM8 (http://www.fil.ion.ucl.ac.uk/spm). The mid-frame (the 16th frame) of the dynamic PIB images and FDG images was coregistered with the corresponding MRI scan, and the PET scans were transformed to the population template with the deformation fields generated in the registration procedure of the MRI scans. Finally, all images were spatially normalized to the Montreal Neurological Institute space.

5.4. Computation of 11C-pPIB Image from Dynamic 11C-PIB Scans

The procedure to compute the 11C-pPIB images from the dynamic PIB scans has been reported previously [10]. Particularly, 11C-pPIB images were computed based on a 7-min time-window of the dynamic 11C-PIB-PET, starting from 9th frame to 15th frame and corresponding to the frames of 1.33–8 min, yielding the highest correlation between 18F-FDG and 11C-PIB (R = 0.87). Also, 11C-PIB and 18F-FDG images shared a similar radioactive distribution pattern in CN, MCI, and AD groups.

5.5. Statistical Analysis

The pICA algorithm (Fusion ICA Toolbox, http://icatb.sourceforge.net, with MATLAB 7.1) was applied to the 11C-pPIB and 18F-FDG images of all the patients to jointly extract statistical factors from the 11C-pPIB and 18F-FDG data and identify their mutual relationship.

The number of independent components was set to eight, based on a previous study [49]. The outputs from the pICA were pairs of 11C-pPIB and 18F-FDG independent components. Their correlation coefficients were indicative of a relationship between the two modalities. The independent components of 11C-pPIB and 18F-FDG data measured the perfusion and metabolic variability among the participants. All components had a threshold at a supra level, |Z| > 1.5, to identify statistically significant regions that contributed to the overall signal of the corresponding components. Correlation coefficients between components of the two imaging modalities were used to identify the most associated pairs of components.

Subsequently, voxel wise 11C-pPIB and 18F-FDG measurements within the most associated pair of components were compared between AD-CN, MCI-CN, and AD-MCI groups using a two-sample t-test. The multiple comparisons were corrected for using the AlphaSim program in REST (http://restfmri.net/forum/rest) with a full-width at half-maximum of 6 mm. The threshold for the group differences was p < 0.05 with the AlphaSim correction (with p < 0.001 threshold and a minimum cluster size of 12 voxels).

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Xi Zhang, Bo Zhou, Zengqiang Zhang, and Pan Wang for patient recruitment; Dayi Yin, Jiajin Liu, and Can Li for technical support; and Xiaojun Zhang and Jian Liu for helping with the PET radiochemistry. This study was sponsored by the Central Health Care Research W2013BJ14 (to Baixuan Xu), National Major Scientific Instruments and Equipment Development Projects 2011YQ030114 (to Jiahe Tian), and the China Postdoctoral Science Foundation 20090461433 and 2013M542515 (to Liping Fu).

Contributor Information

Yong Fan, Email: yong.fan@ieee.org.

Jiahe Tian, Email: tianjh@vip.sina.com.

Disclosure

An earlier version of this work was presented as a poster at the Annual Congress of the European Association of Nuclear Medicine (EANM'17 CME Sessions), 2017.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Authors' Contributions

Liping Fu and Linwen Liu contributed equally to this work.

References

- 1.McKhann G. M., Knopman D. S., Chertkow H., et al. The diagnosis of dementia due to Alzheimer's disease: Recommendations from the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer's Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer's disease. Alzheimer’s & Dementia. 2011;7(3):263–269. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2011.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nihashi T., Yatsuya H., Hayasaka K., et al. Direct comparison study between FDG-PET and IMP-SPECT for diagnosing Alzheimer's disease using 3D-SSP analysis in the same patients. Radiation Medicine - Medical Imaging and Radiation Oncology. 2007;25(6):255–262. doi: 10.1007/s11604-007-0132-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Paulson O. B., Hasselbalch S. G., Rostrup E., Knudsen G. M., Pelligrino D. Cerebral blood flow response to functional activation. Journal of Cerebral Blood Flow & Metabolism. 2010;30(1):2–14. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2009.188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Forsberg A., Engler H., Blomquist G., Långström B., Nordberg A. The use of PIB-PET as a dual pathological and functional biomarker in AD. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Molecular Basis of Disease. 2012;1822(3):380–385. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2011.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rostomian A. H., Madison C., Rabinovici G. D., Jagust W. J. Early 11C-PIB frames and 18F-FDG PET measures are comparable: A study validated in a cohort of AD and FTLD patients. Journal of Nuclear Medicine. 2011;52(2):173–179. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.110.082057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rodriguez-Vieitez E., Carter S. F., Chiotis K., et al. Comparison of early-phase 11C-Deuterium-L-Deprenyl and 11C-Pittsburgh Compound B PET for Assessing Brain Perfusion in Alzheimer Disease. Journal of Nuclear Medicine. 2016;57(7):1071–1077. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.115.168732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Daerr S., Brendel M., Zach C., et al. Evaluation of early-phase [18F]-florbetaben PET acquisition in clinical routine cases. NeuroImage: Clinical. 2017;14:77–86. doi: 10.1016/j.nicl.2016.10.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tiepolt S., Hesse S., Patt M., et al. Early [18F]florbetaben and [11C]PiB PET images are a surrogate biomarker of neuronal injury in Alzheimer’s disease. European Journal of Nuclear Medicine and Molecular Imaging. 2016;43(9):1700–1709. doi: 10.1007/s00259-016-3353-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rodriguez-Vieitez E., Leuzy A., Chiotis K., Saint-Aubert L., Wall A., Nordberg A. Comparability of [18F]THK5317 and [11C]PIB blood flow proxy images with [18F]FDG positron emission tomography in Alzheimer's disease. Journal of Cerebral Blood Flow & Metabolism. 2016;37(2):740–749. doi: 10.1177/0271678X16645593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fu L., Liu L., Zhang J., Xu B., Fan Y., Tian J. Comparison of dual-biomarker PIB-PET and dual-tracer PET in AD diagnosis. European Radiology. 2014;24(11):2800–2809. doi: 10.1007/s00330-014-3311-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McKeown M. J., Jung T.-P., Makeig S., et al. Spatially independent activity patterns in functional MRI data during the Stroop color-naming task. Proceedings of the National Acadamy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1998;95(3):803–810. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.3.803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vigário R., Särelä J., Jousmiki V., Hämäläinen M., Oja E. Independent component approach to the analysis of EEG and MEG recordings. IEEE Transactions on Biomedical Engineering. 2000;47(5):589–593. doi: 10.1109/10.841330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Milne E., Scope A., Pascalis O., Buckley D., Makeig S. Independent Component Analysis Reveals Atypical Electroencephalographic Activity During Visual Perception in Individuals with Autism. Biological Psychiatry. 2009;65(1):22–30. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2008.07.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Grandchamp R., Braboszcz C., Makeig S., Delorme A. Stability of ICA decomposition across within-subject EEG datasets. Conference proceedings: IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society. 2012;2012:6735–6739. doi: 10.1109/EMBC.2012.6347540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Xu L., Groth K. M., Pearlson G., Schretlen D. J., Calhoun V. D. Source-based morphometry: The use of independent component analysis to identify gray matter differences with application to schizophrenia. Human Brain Mapping. 2009;30(3):711–724. doi: 10.1002/hbm.20540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Park H.-J., Kim J.-J., Youn T., Lee D. S., Lee M. C., Kwon J. S. Independent component model for cognitive functions of multiple subjects using [15O]H2O PET images. Human Brain Mapping. 2003;18(4):284–295. doi: 10.1002/hbm.10085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Calhoun V. D., Adali T., Kiehl K. A., Astur R., Pekar J. J., Pearlson G. D. A method for multitask fMRI data fusion applied to schizophrenia. Human Brain Mapping. 2006;27(7):598–610. doi: 10.1002/hbm.20204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tosun D., Schuff N., Shaw L. M., Trojanowski J. Q., Weiner M. W. Relationship between CSF biomarkers of Alzheimer's disease and rates of regional cortical thinning in ADNI data. Journal of Alzheimer's Disease. 2011;26(supplement 3):77–90. doi: 10.3233/jad-2011-0006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Laforce R., Jr., Tosun D., Ghosh P., et al. Parallel ICA of FDG-PET and PiB-PET in three conditions with underlying Alzheimer's pathology. NeuroImage: Clinical. 2014;4:508–516. doi: 10.1016/j.nicl.2014.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Drzezga A., Becker J. A., Van Dijk K. R. A., et al. Neuronal dysfunction and disconnection of cortical hubs in non-demented subjects with elevated amyloid burden. Brain. 2011;134(6):1635–1646. doi: 10.1093/brain/awr066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Myers N., Pasquini L., Göttler J., et al. Within-patient correspondence of amyloid-β and intrinsic network connectivity in Alzheimer's disease. Brain. 2014;137(7):2052–2064. doi: 10.1093/brain/awu103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Raichle M. E., MacLeod A. M., Snyder A. Z., Powers W. J., Gusnard D. A., Shulman G. L. A default mode of brain function. Proceedings of the National Acadamy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2001;98(2):676–682. doi: 10.1073/pnas.98.2.676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Buckner R. L., Andrews-Hanna J. R., Schacter D. L. The brain's default network: anatomy, function, and relevance to disease. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 2008;1124:1–38. doi: 10.1196/annals.1440.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kadir A., Almkvist O., Forsberg A., et al. Dynamic changes in PET amyloid and FDG imaging at different stages of Alzheimer's disease. Neurobiology of Aging. 2012;33(1):198–e14. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2010.06.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Liu L., Fu L., Zhang X., et al. Combination of dynamic 11C-PIB PET and structural MRI improves diagnosis of Alzheimer's disease. Psychiatry Research: Neuroimaging. 2015;233(2):131–140. doi: 10.1016/j.pscychresns.2015.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Buckner R. L., Snyder A. Z., Shannon B. J., et al. Molecular, structural, and functional characterization of Alzheimer's disease: evidence for a relationship between default activity, amyloid, and memory. The Journal of Neuroscience. 2005;25(34):7709–7717. doi: 10.1523/jneurosci.2177-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Seeley W. W., Crawford R. K., Zhou J., Miller B. L., Greicius M. D. Neurodegenerative diseases target large-scale human brain networks. Neuron. 2009;62(1):42–52. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2009.03.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhou J., Gennatas E. D., Kramer J. H., Miller B. L., Seeley W. W. Predicting Regional Neurodegeneration from the Healthy Brain Functional Connectome. Neuron. 2012;73(6):1216–1227. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2012.03.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dennis E. L., Thompson P. M. Functional brain connectivity using fMRI in aging and Alzheimer's disease. Neuropsychology Review. 2014;24(1):49–62. doi: 10.1007/s11065-014-9249-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Brier M. R., Thomas J. B., Snyder A. Z., et al. Loss of intranetwork and internetwork resting state functional connections with Alzheimer's disease progression. The Journal of Neuroscience. 2012;32(26):8890–8899. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5698-11.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shulman R. G., Rothman D. L., Behar K. L., Hyder F. Energetic basis of brain activity: Implications for neuroimaging. Trends in Neurosciences. 2004;27(8):489–495. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2004.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sibson N. R., Dhankhar A., Mason G. F., Behar K. L., Rothman D. L., Shulman R. G. In vivo 13C NMR measurements of cerebral glutamine synthesis as evidence for glutamate-glutamine cycling. Proceedings of the National Acadamy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1997;94(6):2699–2704. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.6.2699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Raichle M. E. The brain's default mode network. Annual Review of Neuroscience. 2015;38:433–447. doi: 10.1146/annurev-neuro-071013-014030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Buckner R. L. Memory and executive function in aging and ad: Multiple factors that cause decline and reserve factors that compensate. Neuron. 2004;44(1):195–208. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2004.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cole M. W., Pathak S., Schneider W. Identifying the brain's most globally connected regions. NeuroImage. 2010;49(4):3132–3148. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2009.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Minoshima S., Giordani B., Berent S., Frey K. A., Foster N. L., Kuhl D. E. Metabolic reduction in the posterior cingulate cortex in very early Alzheimer's disease. Annals of Neurology. 1997;42(1):85–94. doi: 10.1002/ana.410420114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhang D., Snyder A. Z., Shimony J. S., Fox M. D., Raichle M. E. Noninvasive functional and structural connectivity mapping of the human thalamocortical system. Cerebral Cortex. 2010;20(5):1187–1194. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhp182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhou J., Greicius M. D., Gennatas E. D., et al. Divergent network connectivity changes in behavioural variant frontotemporal dementia and Alzheimer's disease. Brain. 2010;133(5):1352–1367. doi: 10.1093/brain/awq075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Caroli A., Prestia A., Chen K., et al. Summary metrics to assess Alzheimer disease-related hypometabolic pattern with 18F-FDG PET: Head-to-head comparison. Journal of Nuclear Medicine. 2012;53(4):592–600. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.111.094946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sokoloff L. Relationships among local functional activity, energy metabolism, and blood flow in the central nervous system. Federation Proceedings. 1981;40(8):2311–2316. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hanyu H., Abe S., Arai H., Asano T., Iwamoto T., Takasaki M. Diagnostic accuracy of single photon emission computed tomography in Alzheimer's disease. Gerontology. 1993;39(5):260–266. doi: 10.1159/000213541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.O'Brien J. T., Eagger S., Syed G. M. S., Sahakian B. J., Levy R. A study of regional cerebral blood flow and cognitive performance in Alzheimer's disease. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery & Psychiatry. 1992;55(12):1182–1187. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.55.12.1182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ćurčić-Blake B., van der Meer L., Pijnenborg G. H. M., David A. S., Aleman A. Insight and psychosis: Functional and anatomical brain connectivity and self-reflection in Schizophrenia. Human Brain Mapping. 2015;36(12):4859–4868. doi: 10.1002/hbm.22955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Li H.-J., Nie X., Gong H.-H., Zhang W., Nie S., Peng D.-C. Abnormal resting-state functional connectivity within the default mode network subregions in male patients with obstructive sleep APNEA. Neuropsychiatric Disease and Treatment. 2016;12, article no. A23:203–212. doi: 10.2147/NDT.S97449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Esposito R., Mosca A., Pieramico V., Cieri F., Cera N., Sensi S. L. Characterization of resting state activity in MCI individuals. PeerJ. 2013;2013(1, article no. e135) doi: 10.7717/peerj.135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Albert M. S., DeKosky S. T., Dickson D., et al. The diagnosis of mild cognitive impairment due to Alzheimer's disease: recommendations from the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer's Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer's disease. Alzheimer’s & Dementia. 2011;7(3):270–279. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2011.03.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lehmann M., Ghosh P. M., Madison C., et al. Diverging patterns of amyloid deposition and hypometabolism in clinical variants of probable Alzheimer's disease. Brain. 2013;136(3):844–858. doi: 10.1093/brain/aws327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Philippe C., Haeusler D., Mitterhauser M., et al. Optimization of the radiosynthesis of the Alzheimer tracer 2-(4-N-[11C]methylaminophenyl)-6-hydroxybenzothiazole ([11C]PIB) Applied Radiation and Isotopes. 2011;69(9):1212–1217. doi: 10.1016/j.apradiso.2011.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Meda S. A., Narayanan B., Liu J., et al. A large scale multivariate parallel ICA method reveals novel imaging-genetic relationships for Alzheimer's disease in the ADNI cohort. NeuroImage. 2012;60(3):1608–1621. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2011.12.076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]