Abstract

Purpose

Parents and caregivers play an important role in sexual socialization of youth, often serving as the primary source of information about sex. For African American rural youth who experience disparate rates of HIV/STI, improving caregiver-youth communication about sexual topics may help to reduce risky behaviors. This study assessed the impact of an intervention to improve sexual topic communication.

Design

Quasi-experimental, pre/posttest, controlled, community-based trial

Setting

Intervention was in two rural NC counties with comparison group in three adjacent counties.

Subjects

Participants (n=249) were parents, caregivers or parental figures for African American youth aged 10–14.

Intervention

Twelve-session curriculum for participating dyads.

Measures

Audio-computer assisted self-interview to assess changes at 9 months from baseline in communication about general and sensitive sex topics and overall communication about sex.

Analysis

Multivariable models were used to examine the differences between the changes in mean of scores for intervention and comparison groups.

Results

Statistically significant differences in changes in mean scores for communication about general sex topics (p<0.0001), communication about sensitive sex topics (p<0.0001), overall communication about sex (p<0.0001) existed. Differences in change in mean scores remained significant after adjusting baseline scores and other variables in the multivariate models.

Conclusions

In TORO, adult participants reported improved communication about sex, an important element to support risk reduction among youth in high prevalence areas.

Key Words and Indexing Key Words: Adult youth communication about sex, risk reduction intervention, community academic partnered research

The risk of acquiring sexually transmitted infections (STIs) and HIV increases significantly between the adolescent and young adult years. The burden of infection is strongest for African Americans (AAs) in southern, rural areas of the United States (US). 1,2 In North Carolina (NC), for example, AAs in rural communities account for 65% of all HIV cases, 19% of whom are children and youth between the ages of 13 and 24. 1,3 High rates of teen pregnancy, STIs, and sexual risk behaviors among youth has remained a source of concern for researchers, practitioners, and parents alike and are associated with behavioral, cultural, and biological factors. 1,4,5

While many interventions have focused on reducing sexual risk behaviors among AA youth, a major critique of many of these programs is their tendency to focus on individual or proximal factors. 6–9 Other risky and problematic behaviors (e.g., teen dating violence, substance use, etc.) tend to surface during the same developmental period as sexual risk behaviors. 10–11 Due to the co-occurrence of risk behaviors, as well as the overlap in ecological predictors during adolescence, multilevel interventions are needed to address co-occurring risk behaviors. 10–11 Moreover, many interventions have been limited as a result of a sole focus on youth and failure to engage others within their social networks. 12 Others have been limited by a sole focus on caregivers, while failing to equally engage youth or engage parents and youth in dyads. 14

Parents and other caregivers, for example, play an important role in the sexual socialization of youth during early adolescence. 18, 15, 16, 19, 20 As a result, including them in intervention efforts could increase the likelihood of positive outcomes, such as higher levels of family functioning, improved attitudes towards condom use, and informed beliefs about birth control. 16

Researchers have been urged to develop intervention programs that not only engage youth, but also engage others who influence the development of health behaviors in youth. Teach One, Reach One (TORO), a multilevel risk reduction program, used community-based participatory research (CBPR) methods to engage youth, parents, peers, and community members in intervention implementation. TORO utilized a Lay Health Advisor (LHA) model to reduce problem behaviors, such as sexual risk and teen dating violence, and increase healthy sexual, dating, and familial relationships among AAs in rural NC. This multi-level approach provides a unique opportunity to examine intervention effects within a rural and resource-limited AA community. Therefore, the purpose of the current study is to describe the effect of TORO on one of the intervention’s primary aims, adult-youth communication about sex.

METHODS

Design

We employed a pre- post-intervention study design to conduct a quasi-experimental, controlled, community-based trial with a comparison group, to determine the impact of TORO on communication about sex. The study and all related procedures were approved by the Institutional Review Board at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill (UNC).

Sample

The study took place in five rural counties in eastern NC (see table 1). Adult and youth in the intervention group were recruited from two rural counties i.e. Edgecombe and Nash, which surround one city. Although separated by county lines, the AA residents in these two counties function as one community because of shared social, cultural, and economic history. Most reside in a racially segregated area that spans the two counties with a railroad track that bisects the area. The counties have 94,000 (37%) and 53,000 (57%) AA residents, respectively. 20 We recruited participants in the comparison group from three adjacent counties i.e. Halifax, Northampton and Wilson, with similar demographic profiles. These counties were part of another feasibility study to disseminate a 12-session diabetes prevention intervention, Power to Prevent (P2P), though we did not recruit directly from those P2P participants. 22 This design allowed us to use a more rigorous study design with a comparison arm, with exposure to another intervention, to address an important health issue in the comparison communities, and to pragmatically address resource constraints. All five counties had higher rates of poverty and STIs compared with the state average, with the highest rates among AA residents. 21

Table 1.

Demographic Characteristics of Intervention and Comparison Counties in 2006

| County | African Americans in County | % African Americans in Poverty | Whites in County | % Whites in Poverty | HIV Cases | Chlamydia Cases | Gonorrhea Cases | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| African Americans | Whites | African Americans | Whites | African Americans | Whites | |||||

| Intervention | ||||||||||

| Edgecombe | 58% | 27% | 40% | 9% | 86% | 11% | 92% | 5% | 92% | 6% |

| Nash | 34% | 23% | 62% | 7% | 82% | 11% | 84% | 9% | 86% | 12% |

| Control | ||||||||||

| Halifax | 53% | 34% | 43% | 11% | 85% | 14% | 85% | 11% | 87% | 8% |

| Northampton | 59% | 29% | 39% | 9% | 89% | 8% | 92% | 6% | 92% | 6% |

| Wilson | 39% | 30% | 40% | 9% | 90% | 8% | 72% | 12% | 81% | 5% |

Recruitment and Informed Consent

A research team comprised of staff from UNC and partnering faith- or community-based organizations recruited participants, organized and facilitated sessions, and monitored the program’s progress. We recruited participating dyads using a variety of strategies that were developed with our community partners. We recruited through local organizations, churches, schools, print media (e.g. fliers, brochures, newspaper) and via radio. Adult individuals, interested in participating were directed to call the study office. A study staff member would provide an overview of the study inclusion criteria, goals and activities. In the intervention counties, we used a screening interview to determine eligibility. During an earlier planning grant, academic and community partners developed a list of characteristics to be considered in the selection of LHAs. 25 Recruitment staff used this list to assess individuals. Adults who were interested and eligible were asked to sign a consent form for themselves and their youth. Youth were asked to sign an assent form. The same recruitment protocol was used to identify youth and adult dyads in the comparison counties.

Eligibility

To be eligible to participate, youth had to self-identify as AA, participate voluntarily, and be between 10 and 14 years of age at recruitment. Youth in early adolescence were targeted because the average age of sexual debut is 13 years in AA youth in this region. 20, 23 Adults had to be over age 18 years and the parent, primary caregiver, or parental figure for a participating youth. In addition, each adult-youth dyad that was recruited into the intervention group had to identify at least one other dyad or more if possible, with whom they would engage during the intervention period and share information they learned during the training. The rationale was to not only to train the trainer and teach back, 24 but to also reinforce the training and importance of communication about sex and risk behaviors among individuals who were not study participants.

Intervention

Intervention Theoretical Framework and Design

Our study was principally driven by a community-based participatory research (CBPR) approach and guided by Intervention Mapping (IM). IM encourages an optimal level of participation of all partners in the planning process; it acknowledges the impact of socio-ecological factors on health outcomes; and it highlights the application of health behavior theory in program development. 14, 26, 27 In addition to health behavior theory, TORO incorporates constructs from the Theory of Planned Behavior to address individual-level factors and Social Cognitive Theory to address the influences of the social environment that influence sexual risk behaviors among AA youth. 11, 27 In addition to parental influence, we have also targeted sexual norms. Multiple studies have shown that adolescents who perceived their peers have engaged in sexual behavior are more likely to also engage in sexual behavior, to have an earlier sexual debut, and to continue the sexual behavior and/or intercourse. 20, 29–37 Existing research also indicates that adolescents who had peers and/or parents who held less favorable attitudes or views about engaging in sexual behavior were more likely to practice abstinence and delay sexual debut. 20, 22, 36, 38–40 While a broader range of behavioral, social, and physical environmental factors may influence HIV/STI risk, our conceptual model was grounded in theory, existing literature, and our assessment of community needs and assets, so the intervention addresses HIV/STI risk among rural AA youth. 28

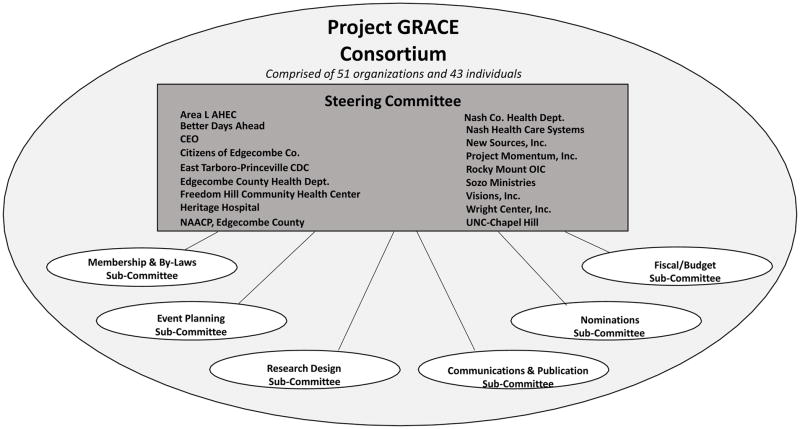

TORO was developed by the Project GRACE (Growing, Reaching, Advocating for Change and Empowerment) Consortium which is an academic-community collaboration between partners that share the common goal of eliminating health disparities in AA communities through CBPR approaches to partnership development and intervention design. The consortium involved a broad representation of community stakeholder organizations including but not limited to: Area L AHEC, Edgecombe and Nash County Health Departments, Heritage Hospital, NAACP, Project Momentum Inc., Nash Health Care Systems, etc. (see figure 1). Using community-based participatory research (CBPR) principles, Intervention Mapping, and drawing on extensive qualitative feedback from community stakeholders across two counties of NC, we designed and implemented TORO to address multiple contributors to risk among AA youth in rural eastern NC. 20, 41 The multiple contributors of risk included in the TORO intervention spanned behavioral (e.g., age of sexual debut), social (e.g., parental influences) and physical (e.g., availability of drugs and alcohol) environmental factors (see figure 2). TORO is a multi-generational intervention consisting of a 12-session HIV/STI risk-reduction program that trains dyads of early adolescents and their adult counterparts (parent, caregiver, or primary parental figure) using social learning and cognitive behavioral approaches. TORO includes two primary components: (1) a curriculum for youth on condom use, healthy dating relationships, and abstinence; and (2) a curriculum for adults on parental monitoring and communication about sexual health and healthy dating (see table 2).

Figure 1.

Project GRACE Organizational Structure

Figure 2.

TORO Conceptual Framework

Table 2.

TORO Intervention Sessions Overview

| Session | Caregiver Session | Youth Session |

|---|---|---|

| Session 1 | Welcome Session | Welcome Session |

| Session 2 | Family Values & Decision Making | Making Plans for Me |

| Session 3 | Healthy Relationships | Healthy Relationships |

| Session 4 | Setting Healthy Boundaries | Setting Limits for Yourself |

| Session 5 | Rules, Boundaries, & Parental Monitoring | Identifying & Resisting Pressure |

| Session 6 | Preparing for “The Big Talk” | Your Body – The Facts |

| Session 7 | Preparing for “The Big Talk” | HIV/STI Facts |

| Session 8 | Consequences of Choosing Abstinence of Choosing to Have Sex | Examining the Consequences of Having Sex as a Teen |

| Session 9 | Helping Youth Navigate | Resisting Pressure |

| Session 10 | Managing Media | Using Condoms |

| Session 11 | Advising Skills, Part 1 | Advising Skills, Part 1 |

| Session 12 | Advising Skills, Part 2 | Advising Skills, Part 2 |

| Session 13 | Graduation | Graduation |

The intervention is divided into a curriculum for youth and one for adults, implemented in twelve weekly 1.5-hour sessions including a welcome and overview session and a graduation ceremony. Whenever possible, we incorporated elements of other evidence-based interventions that included the outcomes or behavioral determinants we were addressing. 14, 28, 41–43 Sessions were sequential, with later sessions building on concepts of earlier ones, and emphasized active learning using a variety of strategies (e.g., games, small and large group discussions, skill practice). The adult curriculum focused on parental monitoring and communication about sex and healthy dating. Each session was structured to target specific behavioral determinants from our guiding theoretical framework and included knowledge, attitudes, skills, self-efficacy, outcome expectations, social support/social networks, and perceived norms for youth and parents on abstinence, condom use, healthy dating, communication, and parental monitoring. The youth curriculum focused on abstinence, condom use, and healthy dating relationships.

Sessions were held on Saturday mornings. To keep the training sessions relatively small and allow for more interactive activities and individualized feedback, 5–10 dyads were trained in each wave. Adult and youth attended sessions separately for the first hour and then together for the last half hour. During the joint session, adults and youth had the opportunity to process what they learned and practice new skills. The dyadic activities included communication skills in pairs and in groups. Some activities focused on communication but others skills were also emphasized using innovative approaches to learning e.g., condom skills relay race or anatomy jeopardy. Participants received lunch and an incentive of $10 for participating in each session.

Data Collection

To address potential low literacy in our participants and afford maximal privacy, we used audio-computer-assisted self-interview (A-CASI) for data collection in both groups. A-CASI has been shown to be more effective than face-to-face interviews or self-administered surveys to elicit valid self-reports of sexual activity. Outcome measures were assessed at baseline and 9 months. The posttest questionnaire assessed parent-teen communication in the last six months, thereby excluding intervention activities from the reported behaviors in the posttest. Participants received a $30 incentive after completing each data collection session.

Measures

We assessed the effectiveness of TORO on communication about sex using the following primary and secondary outcomes.

Communication about Sexual Topics 11

Communication about sexual topics (primary outcome) was assessed with three measures. First, we created an overall measure using a 20-item scale (Cronbach’s alpha = .94) adapted from previously published instruments. 11 Because this scale was combined from multiple sources, we conducted exploratory factor analyses. Two subscales emerged: Communication about General Sex Topics, wherein items were scaled based on the following question: Please remember to think about how often you have talked with the youth in the program about these topics. The topics included menstruation, pregnancy, condom use, etc. This sub-scale included 10 items (Cronbach’s alpha = .91). Similarly, sub-scale 2, Communication about Sensitive Sexual Topics, also assessed how often parents discussed these topics with their children and included items such as satisfaction (orgasm), masturbation, and wet dreams, had 6 items (Cronbach’s alpha = .91). We report results for all three measures because there is some overlap with item distribution between the subscales and the overall measure of communication about sex.

Knowledge of Open Communication

Knowledge of open communication (secondary outcome) was measured using a 4-item True/False scale. 25, 44 The scale was scored based on the number of items answered correctly. Example item: “A good way to open the door of communication is to watch TV or movies with your child and follow that with a discussion about the characters.”

Attitudes toward Communication about Sex Topics

Attitudes toward communication about sexual topics (secondary outcome) was measured using a 10-item scale developed de novo to assess parental beliefs about discussing sex with youth in the study. 45, 46 For example, we assessed level of agreement on: “Parents should talk to their child about dating” and “I am afraid to talk to my child about sex”. Item scores ranged from Strongly Agree to Strongly Disagree, and a composite score was developed by averaging individual items within the different groups. Higher scores indicate more favorable attitudes to talking to youth about sexual topics.

Self-Efficacy of Communication about Sex Topics

Self-Efficacy of communication about sexual topics (secondary outcome) was measured using a 16-item scale (Cronbach’s alpha = .85) created by DiIorio. 11, 44, 45 Adults were asked to rate their confidence in explaining sexual questions such as “How to put on a condom” and “Why an unmarried person should use a condom when they have sex”. The final value for this scale was computed by adding all items, which are scored on a range from 0 = Not Sure at All to 3 =Completely Sure. Higher scores indicate greater self-efficacy.

Frequency of Communication

Adult-youth communication was measured using the Parent-Adolescent Community Scale (PACS) developed by Wingood and Diclemente (5 items), 11 that assessed the frequency of communicating about sexually related topics. The adults were asked, “In the past six months, how often have you and your parent(s) talked about the following things: 1) sex, 2) how to use condoms, 3) protecting yourself from STIs, 4) protecting yourself from the AIDS virus, and 5) protecting yourself from becoming pregnant.”

Demographic Characteristics

We queried adult participants on the following demographic characteristics: gender; race; ethnicity; household income; educational attainment; marital status; employment; insurance status; and relation to enrolled youth.

Analysis

We used data collected at baseline and 9 months from the adults in the intervention and control groups. We calculated descriptive statistics (means, medians, proportions, and standard errors) to summarize baseline sample characteristics and used t tests and chi-square tests to compare these characteristics between adults in the intervention and control groups. We used paired t tests to compare pre-post changes within groups and simple t tests for differences in the mean changes between the intervention and comparison groups for all study outcomes. Similarly, we compared characteristics between those adults who dropped out and those retained in the study. In addition, we used multivariate regression models that included covariates that differed between the intervention and comparison groups (gender, marital status, duration of intervention, relation to the child, and age) along with the baseline value of the outcome variable of interest. All analyses were conducted using SAS 9.2©.

RESULTS

Demographic Characteristics

The average age of our adult sample was 36 years. Most were women (87%), non-Hispanic Blacks (87%) and unemployed (63%), with an annual household income of less than $40,000 (73%) and educational attainment less than a college degree (83%), (see table 3). The majority of adult participants were either parents (63%) or relatives (21%) of youth in the study. There were statistically significant differences between the intervention and comparison groups on gender, race, marital status, relation to the child, and age. In addition, among intervention participants, more than half (n=67, 61%) completed all of the TORO sessions and more than two thirds of the sample (n=99, 91%) completed at least 50%. 62 youths participated in the intervention trial. Their mean age was 12.6 years, half (50%) were female, and most (96.5%) self-identified as AA, with the remainder identifying as multiracial or from an unspecified background. In addition, the dyads that were trained were able to recruit more than 100 allies in the treatment (n=130) and comparison (n=143) groups.

Table 3.

Demographic Characteristics of Adult Teach One Reach One (TORO) Participants and Comparison

| Personal Characteristics | Overall | Intervention | Comparison | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | Est. | na | Est. | n | Est. | p | |

| Gender | |||||||

| Male | 55 | 22.09 | 12 | 13.04 | 43 | 27.39 | 0.008 |

| Female | 194 | 77.91 | 80 | 86.96 | 114 | 72.61 | |

| Raceb | |||||||

| African American | 129 | 86.58 | 80 | 86.96 | 149 | 94.90 | 0.026 |

| Other/Not Reported | 20 | 13.42 | 12 | 13.04 | 8 | 5.10 | |

| Ethnicity | |||||||

| Non-Hispanic/Latino | 237 | 97.53 | 88 | 96.70 | 149 | 98.03 | 0.520 |

| Hispanic/Latino | 6 | 2.47 | 3 | 3.30 | 3 | 1.97 | |

| Income | |||||||

| < $5,000 | 56 | 24.78 | 20 | 25.64 | 36 | 24.32 | 0.997 |

| $5,000–19,999 | 71 | 31.42 | 24 | 30.77 | 47 | 31.76 | |

| $20,000–39,000 | 61 | 26.99 | 21 | 26.92 | 40 | 27.03 | |

| $40,000 or more | 38 | 16.81 | 13 | 16.67 | 25 | 16.89 | |

| Education | |||||||

| < High School (HS) Diploma | 51 | 20.56 | 18 | 19.57 | 33 | 21.15 | 0.683 |

| HS Diploma to Some College or Technical School | 148 | 59.68 | 58 | 63.04 | 90 | 57.69 | |

| College Degree or Higher | 49 | 19.76 | 16 | 17.39 | 33 | 21.15 | |

| Marital Status | |||||||

| Married/Cohabitating | 81 | 32.79 | 35 | 38.04 | 46 | 29.68 | 0.009 |

| Separated/Divorced/Widowed | 55 | 22.27 | 27 | 29.35 | 28 | 18.06 | |

| Never Married | 111 | 44.94 | 30 | 32.61 | 81 | 52.26 | |

| Employed for Wages | |||||||

| Yes | 109 | 44.67 | 34 | 36.96 | 75 | 49.34 | 0.059 |

| No | 135 | 55.33 | 58 | 63.04 | 77 | 50.66 | |

| Relation to Youth | |||||||

| Parent | 137 | 55.02 | 58 | 63.04 | 79 | 50.32 | 0.015 |

| Relative | 45 | 18.07 | 19 | 20.65 | 26 | 16.56 | |

| Friend/Other | 67 | 26.91 | 15 | 16.30 | 52 | 33.12 | |

Totals do not sum to the sample size due to missing data.

“Other/Not Reported” includes 1 adult participant from the comparison group who selected “American Native.”

Primary and Secondary Outcomes

Improvement in communication about general sex topics was greater in the intervention group (p < 0.001) versus the comparison group. The mean difference in the change in scores for the intervention group was significantly larger (p < 0.001) than the mean change in the comparison group and remained so after adjustment for baseline scores on communication about general sex topics and the variables that differed between the two groups (p < 0.001).

In addition, we saw improvements in communication about sensitive sex topics in the intervention group (p < 0.001) versus the comparison group. The mean difference in change of scores was statistically significantly larger for the intervention group compared to the comparison group (p < 0.001) and remained so after adjustment for baseline scores on communication about sensitive sex topics and the variables that differed between the two groups (p < 0.05).

There were statistically significant differences in overall communication about sex. Overall scores improved in both, the intervention group (p < 0.001) and the comparison group. Here, too, the mean difference in the change in scores was significantly larger for the intervention group than for the comparison group (p < 0.001) and remained so after adjustment for baseline scores on overall communication about sex and the variables that differed between the two groups (p < 0.001).

We noted no significant differences in changes in mean score from baseline to post-intervention between the intervention and comparison groups for knowledge of and attitudes towards communication about sexual topics. However, from baseline to post-intervention, self-efficacy of communication about sexual topics improved in the intervention group (p < 0.001). The mean difference between baseline and post-intervention scores was significantly larger for the intervention group than the comparison group (p = 0.007) and remained so after adjustment for baseline self-efficacy score and the variables that differed between the two groups (p < 0.001), (see table 4).

Table 4.

Unadjusted and adjusted difference in mean change in communication scores in adult participants in intervention versus comparison groups

| Outcomes of Interest | Baseline | Post Intervention | Difference in Mean Changes in Scores | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| na | X (SD) | X (SD) | Unadjusted | p | Adjusted b | p | |

| Attitude towards Communication | |||||||

| Intervention | 90 | 15.77 (3.18) | 16.11 (3.05) | 0.38 | 0.466 | 0.42 | 0.308 |

| Comparison | 149 | 15.27 (3.52) | 15.23 (3.17) | ||||

| Knowledge Communication | |||||||

| Intervention | 91 | 0.83 (0.77) | 0.75 (0.64) | −0.10 | 0.433 | −0.11 | 0.322 |

| Comparison | 152 | 0.86 (0.76) | 0.88(0.89) | ||||

| Self-efficacy of Communication | |||||||

| Intervention | 84 | 39.12 (8.29) | 43.37(5.98) | 3.28 | 0.011 | 3.47 | 0.001* |

| Comparison | 144 | 37.15 (10.61) | 38.12(10.04) | ||||

| Communication about General Sex Topics | |||||||

| Intervention | 86 | 16.85 (8.47) | 22.14(6.24) | 5.24 | <.0001 | 3.55 | 0.0002* |

| Comparison | 143 | 17.94 (8.63) | 17.98(8.35) | ||||

| Communication about Sensitive Sex Topics | |||||||

| Intervention | 85 | 5.52 (5.90) | 10.32(6.17) | 4.27 | <.0001 | 2.93 | 0.0002* |

| Comparison | 138 | 7.61 (7.24) | 8.15(6.81) | ||||

| Overall Communication about Sex | |||||||

| Intervention | 85 | 27.49(15.59) | 39.44(13.14) | 11.02 | <.0001 | 7.57 | <.0001* |

| Comparison | 138 | 31.25(17.26) | 32.18(15.96) | ||||

| Frequency of Parent-Teen Communication about General Sex Topics | |||||||

| Intervention | 86 | 16.85 (8.47) | 22.14 (6.24) | 5.24 | <.0001 | 3.56 | 0.0002* |

| Comparison | 143 | 17.94 (8.63) | 17.98 (8.35) | ||||

| Frequency of Parent-Teen Communication about Sensitive Topics | |||||||

| Intervention | 85 | 5.01 (5.24) | 9.21 (5.37) | 3.64 | <.0001 | 2.48 | 0.0009* |

| Comparison | 138 | 6.89 (6.36) | 7.46 (6.11) | ||||

Totals do not sum to the sample size due to missing data.

Models control for variable scores for each outcome, respectively, and demographic (gender, marital status, duration of intervention, relation to the child, and age) variables.

Significant at alpha level < 0.05

Finally, there were statistically significant differences in the overall frequencies of communication about sex. Frequency of communication between adults and youths about general topics increased (p <.0001, unadjusted) for the intervention group. This change remained significant after adjusting the mean change when compared to the control group mean change (p < 0.05). Similar findings were seen for change in the frequency of communication about sensitive topics at the end of TORO among the intervention group which remained significant after adjustment (p < 0.05).

DISCUSSION

Findings from our study provide a glimpse of the multilayered nature of parental communication about sex. The intervention group experienced statistically significant improvements over time in overall communication about sex; more specifically, improvements in domains related to general sex topics (e.g. menstrual cycle) and sensitive sex topics (i.e. masturbation). These finding are consistent with the literature. 47–50 TORO was also successful in enhancing the intervention group’s self-efficacy in communicating about topics such as sexual risk taking, condom use, abstinence, and healthy dating behaviors. Many interventions that aim to increase adults’ self-efficacy in communicating about sex with their child have illustrated similar effects. 49–52 Both of the aforementioned findings are important because research has shown that parents, guardians and caregivers are crucial to helping youth navigate risk and challenges related to sexuality; 53 however, many well-meaning parents fail to effectively communicate with their youth about sex because of perceptions related to their own discomfort, poor knowledge, and inadequate communication skills. 54 Therefore, interventions like TORO that aim to improve parents’ communication about sex topics and their self-efficacy related to communication have the potential to reduce youth sexual risk behaviors.

The TORO intervention did not have an effect on parents’ attitude toward communicating with their youth about sex. A reason for the null finding could be related to sex being a sensitive topic for most parents; therefore, parents discussing sex with their youth may be difficult and seem taboo. This particular finding may be the case for our sample of AA parents who reside in the Southeast “Bible Belt” region of the US and are more likely to be religious and have conservative values 55 that may conflict with openly discussing sex topics. Essentially, their beliefs and values may be the basis for the negative attitude about engaging in discussions related to sex with their youth. As illustrated in a systematic review of parent-child sex communication literature from 1980–2010, there is a dearth of literature on interventions that have explored parental attitudes toward communication. The review cited one intervention study published in 1985 that examined parental attitudes; however, the intervention did not improve parents’ attitudes. 56 The paucity of research regarding attitudes toward communication suggest that we need to conduct more research on this construct as it may be a key barrier and facilitator to parents engaging in conversation with their youth about sex.

The TORO intervention did not have an effect on parents’ knowledge regarding open communication (i.e., displaying appropriate body language, engaging in active listening and effective ways to begin communication, and being nonjudgmental). This finding aligns with the null result related to parental attitudes because tenets of open communication may not resonate with or be perceived as essential for a parent who has a discouraging attitude towards communicating sex information. Nevertheless, it is important to educate parents about the fundamentals of open communication because research has shown that open and frequent communication about sex between parents and youth is linked to delayed sexual debut and increased use of contraceptives. 57 However, additional research is needed to understand if and how attitudes toward communication and knowledge of open communication are associated; this research will help refine our intervention and increase the probability that parents will experience improvements on both constructs.

Limitations

As in all studies, our findings should be considered in the context of its limitations. Our measures of communication were self-report. While consistent with current methods, there is always potential for recall and social desirability bias; even though we intentionally selected A-CASI as a data collection method to mitigate the potential bias. In addition, there were baseline differences in demographic characteristics, which we adjusted for in our multivariable models; however, there may be unmeasured and unequally distributed confounders for which we were unable to control in our analyses. In this community-based controlled study, it was not feasible to randomize or have blind participants in the intervention or comparison groups. However, the statistically significant large differences we found in the intervention group from baseline to post-test on multiple measures of communication suggests the findings are robust. We did not measure actual HIV/STI risk behaviors or examine the relationship between communication and actual HIV/STI risk behaviors. Therefore, we can only hypothesize on TORO’s overarching ability to reduce youth sexual risky behaviors. Future implementation of TORO can focus on investigating links between effective parent-youth communication about sex and actual HIV/STI risk behavior outcomes.

SO WHAT?

What is already known on this topic?

AA youths are three to four times more likely than other ethnic groups to begin sexual activity at an early age. Active and ongoing parental involvement in teen sexual development has been well documented as positively influencing behaviors to reduce sexual risk.

What does this article add?

TORO intervention was effective in improving adult-youth communication about general and sensitive sex topics, frequency, self-efficacy, and knowledge of open communication. Our findings underscore the complex and dynamic nature of parental communication and warrants further research to determine how various aspects of communication may be associated with decreasing risky sexual behaviors among youth.

What are the implications for health promotion practice or research?

Adolescence is characterized by increases in sexual interest, experimentation, and risk; 58 therefore, open and effective adult-youth communication about sexual topics is necessary to facilitate healthy and appropriate sexual development and risk reduction. 59 Caregivers play a critical role in shaping the way in which youth develop and transition from adolescence to adulthood; they are in a unique position to communicate values, beliefs, expectations, and knowledge to youth. 60, 61 Our findings support the feasibility and utility of improving caregiver communication skills as a potential strategy to mitigate sexual risk among youth. In addition, our findings suggest that future research should aim to understand the relationship between attitudes toward communication and knowledge of open communication as a means to refine the TORO intervention and ensure parents engage in positive and open sex health communication with their youth.

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge the contributions of all steering committee members and staff in the development and implementation of Project GRACE: Leslie Atley, Larry Auld, Kelvin Barnhill, Reuben Blackwell, Hank Boyd, III, John Braswell, Angela Bryant, Cheryl Bryant, Don Cavellini, Trinnette Cooper, Danny Ellis, Eugenia Eng, Jerome Garner, Turquoise Griffith, Thomas Griggs, Vernetta Gupton, Davita Harrell, Shannon Hayes-Peaden, Mary Hedgepeth, Stacey Henderson, Doris Howington, Christine Kirby, Clara Knight, Gwendolyn Knight, Taro Knight, Shirly McFarlin, Hilda Morris, Melvin Muhammad, Jamie Newsome, Patricia Oxendine-Pitt, Donald Parker, Tammi Phillips, Stepheria Sallah, Reginald Silver, Doris Stith, Jevita Terry, Chris Williams, Cynthia Worthy, Mysha Wynn and Selena Youmans, Kelly Marie Eason, Sable Noelle Watson, and Phenesse Dunlap.

Funding

This work was funded by grants from the National Center on Minority Health and Health Disparities (R24MD001671), The University of North Carolina Center for AIDS Research (UNC CFAR P30 AI50410), and the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (K24 HL 105493-01). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of any of the funding agencies.

Contributor Information

Gaurav Dave, NC TraCS Institute, Associate Professor, Department of Medicine, Evaluation Chair, Southeast Genetics Regional Collaborative, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, 160 N Medical Dr. CB 7064, Chapel Hill, NC 27599, O: 919-843-9632, F: 919-843-0419.

Tiarney Ritchwood, Department of Social Medicine, 333 South Columbia Street, MacNider Hall, Room #343/CB #7240, Chapel Hill NC 27599-7240.

Tiffany L. Young, NC TraCS Institute, Community Academic Resources for Engaged Scholarship, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, 220-35 Brinkhous-Bullitt, 160 N. Medical Dr. CB # 7064, Chapel Hill, NC 27599-7064, O: 919-843-9626, F: (919) 843-0419.

Malika Roman Isler, Department of Social Medicine – School of Medicine, The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Campus Box 7240, 342B MacNider Hall, Chapel Hill, NC 27599, O: 919-843-4505, F: 919-966-7499.

Adina Black, NC TraCS Institute, Community Academic Resources for Engaged Scholarship, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, 220-35 Brinkhous-Bullitt, 160 N. Medical Dr. CB # 7064, Chapel Hill, NC 27599-7064, O: (919) 843-9214, F: (919) 843-0419.

Aletha Y. Akers, Assistant Professor, Department of Obstetrics, Gynecology and Reproductive Sciences, Assistant Investigator, Magee-Womens Research Institute, Magee-Womens Hospital, 300 Halket Street, Pittsburgh, PA 15213, O: (412) 641-8756, F: (412) 641-1133.

Ziya Gizlice, Director of Biostatistical Support Unit, Center for Health Promotion and Disease Prevention, UNC Chapel Hill, 1700 Martin L King Jr Blvd, O: (919) 966-6040, F: (919) 966-6264.

Connie Blumenthal, Sheps Center for Health Services Research, 725 Martin Luther King Jr. Blvd, CB#7590, Chapel Hill, NC 27599-7590, O: (919) 843-5760, F: (919) 966-3811.

Leslie Atley, Cecil G. Sheps Center for Health Services Research, The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, 725 Martin Luther King Jr. Blvd, Chapel Hill, NC 27599-7590, O: (919)843-6637.

Mysha Wynn, Project Momentum, Inc., PO Box 4053, Rocky Mount, NC 27803, O: (252)458-5350.

Doris Stith, Community Enrichment Organization Family Resource Center, PO Box 1647, Tarboro, NC 27886, O: (252) 823-1733.

Crystal Cene, Division of General Internal Medicine, 5034 Old Clinic Building, CB#7110, Chapel Hill, NC 27599, O: 919-966-2276 ext. 224, F: 919-966-2274.

Danny Ellis, Ellis Research & Consulting Service, LLC., 3514 Whetstone Place, Wilson, NC 27896, O: (252) 230-0406, F: (252) 243-7266.

Giselle Corbie-Smith, Department of Social Medicine, Department of Medicine, UNC-Chapel Hill School of Medicine, Director, Center for Health Equity Research.

References

- 1.Center for Disease and Prevention Control. HIV among youth. 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ohl ME, Perencevich E. Frequency of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) testing in urban vs. rural areas of the United States: Results from a nationally-representative sample. BMC Public Health. 2011;11(1):681. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-11-681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Clymore J. Epidemiologic profile HIV/Std prevention & care planning. North Carolina Department Of Health And Human Services; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Sexually transmitted disease surveillance. 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Metzger I, Cooper SM, Zarrett N, Flory K. Culturally sensitive risk behavior prevention programs for African American adolescents: A systematic analysis. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review. 2013;16(2):187–212. doi: 10.1007/s10567-013-0133-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brody GH, Murry VM, Gerrard M, et al. The strong African American families program: Translating research into prevention programming. Child Development. 2004;75(3):900–917. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2004.00713.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Maticka-Tyndale E, Barnett JP. Peer-led interventions to reduce HIV risk of youth: a review. Evaluation and Program Planning. 2010;33(2):98–112. doi: 10.1016/j.evalprogplan.2009.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Goesling B, Colman S, Trenholm C, Terzian M, Moore K. Programs to reduce teen pregnancy, sexually transmitted infections, and associated sexual risk behaviors: a systematic review. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2014;54(5):499–507. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2013.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Caruthers, Allison S, Mark JVR, Thomas JD. Preventing high-risk sexual behavior in early adulthood with family interventions in adolescence: Outcomes and developmental processes. Prevention Science. 2014;15(1):59–69. doi: 10.1007/s11121-013-0383-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kogan SM, Brody GH, Molgaard VK, et al. The Strong African American Families–Teen trial: Rationale, design, engagement processes, and family-specific effects. Prevention Science. 2012;13(2):206–217. doi: 10.1007/s11121-011-0257-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sales J, Milhausen R, DiClemente RJ. A decade in review: building on the experiences of past adolescent STI/HIV interventions to optimise future prevention efforts. Sexually Transmitted Infections. 2006;82(6):431–436. doi: 10.1136/sti.2005.018002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sutton MY, Lasswell SM, Lanier Y, Miller KS. Impact of parent-child communication interventions on sex behaviors and cognitive outcomes for Black/African-American and Hispanic/Latino youth: A systematic review, 1988–2012. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2014;54(4):369–384. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2013.11.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wight D, Fullerton D. A review of interventions with parents to promote the sexual health of their children. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2013;52(1):4–27. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2012.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Corbie-Smith G, Akers A, Blumenthal C, et al. Intervention mapping as a participatory approach to developing an HIV prevention intervention in rural African American communities. AIDS Education and Prevention: Official Publication of the International Society for AIDS Education. 2010;22(3):184. doi: 10.1521/aeap.2010.22.3.184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cavaleri MA, Olin SS, Kim A, Hoagwood KE, Burns BJ. Family support in prevention programs for children at risk for emotional/behavioral problems. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review. 2011;14(4):399–412. doi: 10.1007/s10567-011-0100-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Miller KS, Fasula AM, Dittus P, Wiegand RE, Wyckoff SC, McNair L. Barriers and facilitators to maternal communication with preadolescents about age-relevant sexual topics. AIDS and Behavior. 2009;13(2):365–374. doi: 10.1007/s10461-007-9324-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bangpan M, Operario D. Understanding the role of family on sexual-risk decisions of young women: A systematic review. AIDS Care. 2012;24(9):1163–1172. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2012.699667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Miller BC. Family influences on adolescent sexual and contraceptive behavior. Journal of Sex Research. 2002;39(1):22–26. doi: 10.1080/00224490209552115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Short MB, Rosenthal SL. Psychosocial development and puberty. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 2011;1135(1):36–42. doi: 10.1196/annals.1429.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Miller KS, Levin ML, Whitaker DJ, Xu X. Patterns of condom use among adolescents: The impact of mother-adolescent communication. American Journal of Public Health. 1998;88(10):1542–1544. doi: 10.2105/ajph.88.10.1542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Clawson CL, Reese-Weber M. The amount and timing of parent-adolescent sexual communication as predictors of late adolescent sexual risk-taking behaviors. Journal of Sex Research. 2003;40(3):256–265. doi: 10.1080/00224490309552190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Diiorio C, Dudley WN, Kelly M, Soet JE, Mbwara J, Sharpe Potter J. Social cognitive correlates of sexual experience and condom use among 13-through 15-year-old adolescents. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2001;29(3):208–216. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(00)00200-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fox GL, Inazu JK. Patterns and outcomes of mother-daughter communication about sexuality. Journal of Social Issues. 1980;36(1):7–29. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Orfaly RA, Frances JC, Campbell P, Whittemore B, Joly B, Koh H. Train-the-trainer as an Educational Model in Public Health Preparedness. Journal of Public Health Management and Practice. 2005;11(6):S123–S127. doi: 10.1097/00124784-200511001-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Parkes A, Henderson M, Wight D, Nixon C. Is parenting associated with teenagers’ early sexual Risk-Taking, autonomy and relationship with sexual partners? Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health. 2011;43(1):30–40. doi: 10.1363/4303011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.US Census Bureau. State and county QuickFacts 2008: Small area income and poverty estimates. 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 27.NC Department of Health and Human Services. North Carolina epidemiologic profile for HIV/STD prevention & care planning. 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 28.Prevention Center for Disease Control. Morbidity and mortality weekly report. 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gillmore MR, Archibald ME, Morrison DM, et al. Teen sexual behavior: Applicability of the theory of reasoned action. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2002;64(4):885–897. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Collazo AA. Theory-based predictors of intention to engage in precautionary sexual behavior among Puerto Rican high school adolescents. Journal of HIV/AIDS Prevention in Children & Youth. 2004;6(1):91–120. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kinsman SB, Romer D, Furstenberg FF, Schwarz DF. Early sexual initiation: the role of peer norms. Pediatrics. 1998;102(5):1185–1192. doi: 10.1542/peds.102.5.1185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sieverding JA, Adler N, Witt S, Ellen J. The influence of parental monitoring on adolescent sexual initiation. Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine. 2005;159(8):724–729. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.159.8.724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Flores LY, O’Brien KM. The career development of Mexican American adolescent women: A test of social cognitive career theory. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 2002;49(1):14. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Marín B, Coyle KK, Gómez CA, Carvajal SC, Kirby DB. Older boyfriends and girlfriends increase risk of sexual initiation in young adolescents. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2000;27(6):409–418. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(00)00097-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Teitler JO, Weiss CC. Effects of neighborhood and school environments on transitions to first sexual intercourse. Sociology of Education. 2000:112–132. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Stanton B, Li X, Black M, et al. Sexual practices and intentions among preadolescent and early adolescent low-income urban African-Americans. Pediatrics. 1994;93(6):966–973. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nahom D, Wells E, Gillmore MR, et al. Differences by gender and sexual experience in adolescent sexual behavior: Implications for education and HIV prevention. Journal of School Health. 2001;71(4):153–158. doi: 10.1111/j.1746-1561.2001.tb01314.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Watts GF, Nagy S. Sociodemographic factors, attitudes, and expectations toward adolescent coitus. American Journal of Health Behavior. 2000;24(4):309–317. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Carvajal SC, Parcel GS, Basen-Engquist K, et al. Psychosocial predictors of delay of first sexual intercourse by adolescents. Health Psychology. 1999;18(5):443. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.18.5.443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Santelli JS, Kaiser J, Hirsch L, Radosh A, Simkin L, Middlestadt S. Initiation of sexual intercourse among middle school adolescents: The influence of psychosocial factors. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2004;34(3):200–208. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2003.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Coyle K. Draw the line/respect the line: A randomized trial of middle school intervention to reduce sexual risk behaviors. American Journal of Public Health. 2004;94(5) doi: 10.2105/ajph.94.5.843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cene CW, Haymore LB, Ellis D, et al. Implementation of the power to prevent diabetes prevention educational curriculum into rural African American communities: A feasibility study. Diabetes Education. 2013;39(6):776–785. doi: 10.1177/0145721713507114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lauby J, Smith P, Stark M, Person B, Adams J. A community-level prevention intervention for inner city women: Results of the women and infants demonstration projects. AJPH. 2000;90(2):216–222. doi: 10.2105/ajph.90.2.216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Basen-Engquist K, Masse L, Coyle K, et al. Validity of scales measuring the psychosocial determinants of HIV/STD-related risk behavior in adolescents. Health Education Research. 1999;14(1):25–38. doi: 10.1093/her/14.1.25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Jemmott JB, Jemmott LS, Braverman PK, Fong GT. HIV/STD risk reduction interventions for African American and Latino adolescent girls at an adolescent medicine clinic: a randomized controlled trial. Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine. 2005;159(5):440–449. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.159.5.440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Siegel DM, Aten MJ, Roghmann KJ, Enaharo M. Early effects of a school-based human immunodeficiency virus infection and sexual risk prevention intervention. Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine. 1998;152(10):961–970. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.152.10.961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Brown LK, Hadley W, Donenberg GR. Project STYLE: A Multisite RCT for HIV Prevention among Youths in Mental Health Treatment. Psychiatric Services. 2014 doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.201300095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Caldwell CH, Rafferty J, Reischl TM, De Loney EH, Brooks CL. Enhancing parenting skills among nonresident African American fathers as a strategy for preventing youth risky behaviors. American Journal of Community Psychology. 2010;45(1–2):17–35. doi: 10.1007/s10464-009-9290-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Diiorio C, McCarty F, Resnicow K, Lehr S, Denzmore P. REAL men: A group-randomized trial of an HIV prevention intervention for adolescent boys. Journal Information. 2007;97(6) doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.073411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Schuster MA, Corona R, Elliott MN. Evaluation of Talking Parents, Healthy Teens, a new worksite based parenting programme to promote parent-adolescent communication about sexual health: randomized controlled trial. BMJ. 2008:337. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39609.657581.25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Forehand R, Armistead L, Long N. Efficacy of a parent-based sexual-risk prevention program for African American preadolescents: a randomized controlled trial. Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine. 2007;161(12):1123–1129. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.161.12.1123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.O’Donnell L, Stueve A, Agronick G, et al. Saving sex for later: An evaluation of a parent education intervention. Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health. 2005;37(4):166–173. doi: 10.1363/psrh.37.166.05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Markham CM, Lormand D, Gloppen KM. Connectedness as a predictor of sexual and reproductive health outcomes for youth. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2010;46(3):S23–S41. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2009.11.214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Huberman B. Learning about Sex: Resource Guide for Sex Educators. Advocates for Youth. 2005 [Google Scholar]

- 55.Taylor RJ, Mattis J, Chatters LM. Subjective religiosity among African Americans: A synthesis of findings from five national samples. Journal of Black Psychology. 1999;25(4):524–543. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Akers AY, Holland CL, Bost J. Interventions to improve parental communication about sex: a systematic review. Pediatrics. 2011:2010–2194. doi: 10.1542/peds.2010-2194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hutchinson MK, Jemmott JB, III, Sweet Jemmott L, Braverman P, Fong GT. The role of mother–daughter sexual risk communication in reducing sexual risk behaviors among urban adolescent females: a prospective study. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2003;33(2):98–107. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(03)00183-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Coker AL, Richter DL, Valois RF, et al. Correlates and consequences of early initiation of sexual intercourse. Journal of School Health. 1994;64(9):372–377. doi: 10.1111/j.1746-1561.1994.tb06208.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Li X, Stanton B, Cottrell L, et al. Patterns of initiation of sex and drug-related activities among urban low-income African-American adolescents. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2001;28(1):46–54. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(00)00173-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.DeVore ER, Ginsburg KR. The protective effects of good parenting on adolescents. Current Opinion in Pediatrics. 2005;17(4):460–465. doi: 10.1097/01.mop.0000170514.27649.c9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Huebner AJ, Howell LW. Examining the relationship between adolescent sexual risk-taking and perceptions of monitoring, communication, and parenting styles. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2003;33(2):71–78. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(03)00141-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]