Abstract

This study assessed the efficacy and safety of ribavirin‐free coformulated glecaprevir/pibrentasvir (G/P) in patients with hepatitis C virus genotype 3 infection with prior treatment experience and/or compensated cirrhosis, a patient population with limited treatment options. SURVEYOR‐II, Part 3 was a partially randomized, open‐label, multicenter, phase 3 study. Treatment‐experienced (prior interferon or pegylated interferon ± ribavirin or sofosbuvir plus ribavirin ± pegylated interferon therapy) patients without cirrhosis were randomized 1:1 to receive 12 or 16 weeks of G/P (300 mg/120 mg) once daily. Treatment‐naive or treatment‐experienced patients with compensated cirrhosis were treated with G/P for 12 or 16 weeks, respectively. The primary efficacy endpoint was the percentage of patients with sustained virologic response at posttreatment week 12 (SVR12). Safety was evaluated throughout the study. There were 131 patients enrolled and treated. Among treatment‐experienced patients without cirrhosis, SVR12 was achieved by 91% (20/22; 95% confidence interval [CI], 72‐97) and 95% (21/22; 95% CI, 78‐99) of patients treated with G/P for 12 or 16 weeks, respectively. Among those with cirrhosis, SVR12 was achieved by 98% (39/40; 95% CI, 87‐99) of treatment‐naive patients treated for 12 weeks and 96% (45/47; 95% CI, 86‐99) of patients with prior treatment experience treated for 16 weeks. No adverse events led to discontinuation of study drug, and no serious adverse events were related to study drug. Conclusion: Patients with hepatitis C virus genotype 3 infection with prior treatment experience and/or compensated cirrhosis achieved high SVR12 rates following 12 or 16 weeks of treatment with G/P. The regimen was well tolerated. (Hepatology 2018;67:514‐523).

Abbreviations

- AE

adverse event

- ALT

alanine aminotransferase

- CI

confidence interval

- DAA

direct‐acting antiviral

- DCV

daclatasvir

- GLE

glecaprevir

- G/P

GLE/PIB

- GT

genotype

- HCV

hepatitis C virus

- IFN

interferon

- NS

nonstructural protein

- peg

pegylated

- PIB

pibrentasvir

- RBV

ribavirin

- SOF

sofosbuvir

- SVR12

sustained virologic response at posttreatment week 12

- VEL

velpatasvir

Infection with hepatitis C virus (HCV) genotype (GT) 3 is associated with higher rates of liver steatosis,1, 2, 3 and achieving sustained virologic response quantifiably reverses its progression in those patients.4, 5, 6 GT3 has been shown to be an independent predictor of fibrosis progression7, 8 and is associated with a higher incidence of hepatocellular carcinoma.9 Thus, effective HCV treatment options are critical for patients with HCV GT3 infection, particularly those with advanced liver disease and/or prior treatment experience.

GT3 is considered the most difficult‐to‐cure genotype with currently available ribavirin (RBV)–free direct‐acting antiviral (DAA) regimens, particularly in patients with cirrhosis and/or prior treatment experience. Sofosbuvir (SOF) and daclatasvir (DCV) for 12 weeks resulted in suboptimal rates of sustained virologic response at posttreatment week 12 (SVR12) in treatment‐naive and treatment‐experienced patients with HCV GT3 infection and compensated cirrhosis (58% and 69%, respectively)10; addition of RBV and/or extended therapy duration modestly increased SVR12 rates in these populations.11 Current treatment guidelines recommend SOF + DCV with or without RBV for 24 weeks in patients with GT3 infection and compensated cirrhosis.12, 13 The DAA combination of SOF and velpatasvir (VEL) for 12 weeks resulted in SVR12 rates between 89% and 91% for HCV GT3‐infected patients with compensated cirrhosis and/or prior treatment experience.14 The American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases recommends viral resistance testing prior to treatment with SOF/VEL in treatment‐naive patients with compensated cirrhosis or in prior pegylated interferon (pegIFN)/RBV treatment‐experienced patients without cirrhosis; coadministration of weight‐based RBV is recommended if testing for Y93H is positive.12 Additionally, the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases recommends 12 weeks of SOF/VEL plus RBV, regardless of viral resistance testing, for prior pegIFN/RBV treatment‐experienced patients with compensated cirrhosis, in part based on a modest increase in SVR12 rate observed with RBV coadministration in patients with cirrhosis and prior IFN‐based treatment experience.15 The European Association for the Study of the Liver recommends that patients with compensated cirrhosis and/or prior treatment experience who test positive for Y93H in nonstructural protein 5A (NS5A) should also have weight‐based RBV coadministered with SOF/VEL.13

Most recently the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases recommended 12 weeks of glecaprevir/pibrentasvir for treatment‐naive patients with GT3 infection and compensated cirrhosis, without the need for viral resistance testing or RBV coadministration. For GT3 patients with prior treatment experience, glecaprevir/pibrentasvir is recommended for 16 weeks, regardless of cirrhosis status. Glecaprevir (GLE) is an HCV NS3/4A protease inhibitor that has pangenotypic antiviral activity, with half‐maximal effective concentration values ≤5 nanomolar across all major HCV GTs.16 Pibrentasvir (PIB) is a novel pangenotypic NS5A inhibitor with half‐maximal effective concentration values of <5 pM across all major HCV GTs and a high barrier to resistance and maintains activity against single–amino acid substitutions known to confer high degrees of resistance to earlier‐generation NS5A inhibitors.17, 18 Importantly, resistance‐associated NS5A substitutions in HCV GT3, such as M28T, A30K, and Y93H, each confer a <2.5‐fold increase to the half‐maximal effective concentration of PIB.17, 18 In addition, both GLE and PIB have negligible renal excretion and do not require dose adjustment for patients with end‐stage renal disease19 and thus are suitable for HCV GT3‐infected patients with severe renal impairment, for whom there are currently limited treatment options.

The US Food and Drug Administration and the European Medicines Agency recently approved the RBV‐free, once‐daily GLE/PIB (G/P) coformulation as a treatment for all six major HCV genotypes in patients without cirrhosis and with compensated cirrhosis.20 In phase 2 studies of patients with HCV GT3 infection, GLE and PIB for 12 weeks was well tolerated and resulted in SVR12 rates of 92% and 100% in treatment‐experienced patients without cirrhosis and treatment‐naive patients with compensated cirrhosis, respectively.21 These results supported initiation of SURVEYOR‐II Part 3, which further assessed the efficacy and safety of G/P in patients with HCV GT3 infection, including the most difficult‐to‐treat population: those with compensated cirrhosis and/or prior HCV treatment experience.

Patients and Methods

STUDY OVERVIEW AND TREATMENT

Part 3 of SURVEYOR‐II (NCT02243293) was a phase 3, partially randomized, open‐label, multicenter study that assessed the efficacy and safety of G/P in adults with chronic HCV GT3 infection, including those with compensated cirrhosis and/or prior HCV treatment experience. All patients signed informed consent, and the study was conducted in accordance with the International Conference on Harmonization guidelines and the ethics set forth by the Declaration of Helsinki. The full trial protocol is available as part of the Supporting Information.

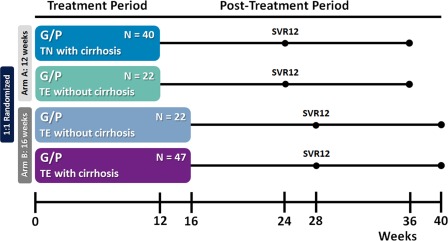

STUDY DESIGN

A schematic of the trial design is outlined in Fig. 1, and the flow of patients through the trial is shown in Supporting Fig. S1. Treatment‐experienced patients without cirrhosis were randomized 1:1 to receive either 12 or 16 weeks of coformulated GLE (discovered by AbbVie and Enanta) and PIB (G/P). Treatment‐naive or treatment‐experienced patients with compensated cirrhosis received G/P for 12 or 16 weeks, respectively. For all patients, G/P was orally dosed once‐daily as three 100 mg/40 mg tablets, for a total dose of 300 mg /120 mg.

Figure 1.

SURVEYOR‐II, Part 3 study design. Patients were enrolled into two arms to be treated with either 12 weeks (arm A) or 16 weeks (arm B) of G/P. Treatment‐naive patients with cirrhosis received 12 weeks of treatment, while those with prior treatment experience and cirrhosis received 16 weeks. Patients with prior treatment experience but without cirrhosis were randomized 1:1 for treatment with either 12 or 16 weeks of G/P. Patients were followed for 24 weeks posttreatment to monitor safety and sustained virologic response. Abbreviations: TE, treatment‐experienced; TN, treatment‐naive.

PATIENT POPULATION

Patients were screened in the United States, Australia, Canada, France, New Zealand, and the United Kingdom. Patients 18 years of age or older (no upper limit) were eligible if they had chronic HCV GT3 infection with HCV RNA >1,000 IU/mL at screening. Patients were either treatment‐naive or treatment‐experienced (previously treated with IFN or pegIFN ± RBV or SOF + RBV ± pegIFN regimens; those previously treated with NS5A or NS3/4A protease inhibitors were excluded). HCV genotype was assessed with the Versant HCV Genotype Inno LiPA Assay, version 2.0 or higher, or Sanger sequencing of the NS5B region, if necessary. The absence of cirrhosis (e.g., METAVIR score ≤ 3, Ishak score ≤ 4) was determined by a liver biopsy within 24 months prior to (or during) screening, a transient elastography (e.g., FibroScan) score of < 12.5 kPa within 6 months prior to (or during) screening, or a screening FibroTest score of ≤0.48 and an aspartate aminotransferase to platelet ratio index <1. The presence of cirrhosis was delineated by a prior histologic diagnosis of cirrhosis on liver biopsy (e.g., METAVIR score of >3 [including 3/4], Ishak score of >4), a prior transient elastography (e.g., FibroScan) score of ≥ 14.6 kPa, or a screening FibroTest score of ≥0.75 and an aspartate aminotransferase to platelet ratio index >2. Indeterminate FibroScan or FibroTest scores required qualifying liver biopsy or FibroScan (to confirm indeterminate FibroTest scores only) to determine cirrhosis status.

Patient exclusion criteria included coinfection with hepatitis B virus, human immunodeficiency virus, or non‐GT3 HCV. Details on laboratory abnormality criteria (e.g., alanine aminotransferase [ALT], platelets, and albumin), as well as all other inclusion and exclusion criteria, are shown in Supporting Table S1.

ASSESSMENT OF EFFICACY, SAFETY, AND VIROLOGIC RESISTANCE

The primary endpoint was the percentage of patients who achieved SVR12 (HCV RNA below the lower limit of quantification 12 weeks after the end of treatment). Secondary endpoints included the percentage of patients with on‐treatment virologic failure and posttreatment relapse. Plasma samples were collected at screening, days 1 and 3, weeks 1 and 2, every other week thereafter during the on‐treatment period (or in the event of premature discontinuation), and posttreatment weeks 2, 4, 8, 12, and 24. Plasma HCV RNA levels were determined for each collected sample using the Roche COBAS TaqMan real‐time reverse transcriptase PCR assay v2.0 with high pure system. The lower limit of detection for this assay was an HCV RNA of 15 IU/mL, and the lower limit of quantification was 25 IU/mL.

Patients receiving at least one dose of study drug were included in safety analyses, which included assessments of adverse events (AEs), vital signs, physical examinations, electrocardiograms, and laboratory tests. Treatment‐emergent AEs were collected from the first administration of study drug until 30 days after study drug discontinuation. Assessment of the relatedness of each AE with respect to study drugs was determined by the treating physician, and the AE, as assigned by the study investigator, was classified using the MedDRA version 19.0 system organ class and preferred term.

Next‐generation sequencing was conducted using a 15% detection threshold to detect the presence of baseline polymorphisms in NS3 and NS5A relative to subtype‐specific reference sequences. Treatment‐emergent substitutions in NS3 and NS5A, defined as substitutions that were present at the time of failure were analyzed for patients who had virologic failure. Additional information on resistance analyses is available in the Supporting Information.

STATISTICAL ANALYSES

No formal statistical hypothesis was to be tested in this study; for this reason, initial patient enrollment goals were not designed to power statistical comparisons but were driven by availability of smaller patient subgroups within the study (e.g., treatment‐experienced patients with cirrhosis). The intent‐to‐treat population was defined as all patients receiving at least one dose of study drug and was used to calculate the percentage of patients achieving SVR12 in each arm. Additional prespecified analyses assessed outcomes in subpopulations within or across arms (e.g., treatment‐experienced patients without cirrhosis). All confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated as two‐sided 95% CIs using the Wilson score method for binomial proportions. Statistical summaries were performed using SAS software.

Results

BASELINE PATIENT DEMOGRAPHICS

In total, 189 patients were screened between January 15, 2016, and April 5, 2016; 57 patients failed screening, and 132 patients with HCV GT3 infection were enrolled and 131 were treated (Supporting Fig. S1). Forty‐four treatment‐experienced patients without cirrhosis were randomized (1:1) to receive either 12 or 16 weeks of G/P. Among patients with compensated cirrhosis, 40 treatment‐naive patients were assigned to G/P for 12 weeks, while 47 treatment‐experienced patients were assigned to 16 weeks of G/P treatment. Overall, a majority of patients were male (67%) and white (89%), and the mean baseline HCV RNA was 6.20 log10 IU/mL. Among patients with prior HCV treatment experience (with or without cirrhosis), 46% (42/91) had prior SOF‐based treatment; 37 of them were previously treated with SOF plus RBV alone, while 5 were treated with SOF plus pegIFN/RBV. Baseline NS5A polymorphisms were detected in 24/129 (19%) patients. Demographics and baseline characteristics were comparable among the treatment‐experienced patients without cirrhosis randomized to 12 or 16 weeks of treatment. Complete patient demographics and baseline characteristics are available in Table 1.

Table 1.

Patient Demographics and Baseline Characteristics

| Arm A (12 Weeks G/P) | Arm B (16 Weeks G/P) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1:1 Randomized | ||||

| Characteristic | Treatment‐Naive With Cirrhosis (n = 40) | Treatment‐Experienced Without Cirrhosis (n = 22) | Treatment‐Experienced Without Cirrhosis (n = 22) | Treatment‐Experienced With Cirrhosis (n = 47) |

| Male, n (%) | 24 (60) | 14 (64) | 14 (64) | 36 (77) |

| White race, n (%) | 37 (93) | 17 (77) | 20 (91) | 42 (89) |

| Age, median years (range) | 56 (36‐70) | 56 (35‐68) | 59 (29‐66) | 59 (47‐70) |

| IL28B non‐CC genotype | 20 (50) | 15 (68) | 19 (86) | 34 (72) |

| BMI, median kg/m2 (range) | 29 (21‐51) | 26 (19‐42) | 28 (22‐48) | 27 (21‐42) |

| HCV RNA, median log10 IU/mL (range) | 6.2 (4.2‐7.1) | 6.6 (5.1‐7.5) | 6.1 (4.7‐7.3) | 6.5 (4.6‐7.2) |

| Baseline ALT, mean U/L (±SD) | 127.1 (±94.0) | 92.2 (±54.7) | 78.6 (±65.8) | 120.5 (±82.1) |

| Total bilirubin, mean mg/dL (±SD) | 0.67 (±0.34) | 0.52 (±0.17) | 0.60 (±0.22) | 0.76 (±0.45) |

| Platelets, median × 109/L (range) | 140 (64‐405) | 210 (105‐291) | 235 (132‐365) | 123 (62‐315) |

| Albumin, median g/L (range) | 39 (29‐47) | 41 (35‐45) | 42 (38‐48) | 40 (33‐47) |

| Prior treatment history, n (%) | ||||

| Naive | 40 (100) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| IFN/pegIFN ± RBV | 0 | 14 (64) | 13 (59) | 22 (47) |

| SOF + RBV ± pegIFN | 0 | 8 (36) | 9 (41) | 25 (53) |

| Baseline fibrosis stage,a n (%) | ||||

| F0‐F1 | 0 | 11 (50) | 15 (68) | 0 |

| F2 | 0 | 4 (18) | 2 (9) | 0 |

| F3 | 0 | 7 (32) | 5 (23) | 0 |

| F4 | 40 (100) | 0 | 0 | 47 (100) |

| Child‐Pugh score, n (%) | ||||

| 5 | 35 (88) | 0 | 0 | 37 (79) |

| 6 | 5 (13) | 0 | 0 | 10 (21) |

| Baseline polymorphisms, n (%)a | ||||

| Any polymorphism | 10 (26) | 6 (27) | 3 (14) | 7 (15) |

| NS3 only | 1 (3) | 0 | 0 | 1 (2) |

| NS5A only | 9 (23) | 6 (27) | 3 (14) | 6 (13) |

| Both NS3 and NS5A | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

Data missing for 1 patient in arm A (column 1) and 1 patient in arm B (column 3); percentages calculated with modified numbers reflecting this. Baseline polymorphisms detected by next‐generation sequencing at a 15% threshold in samples that had sequences available for both targets at amino acid positions 155, 156, and 168 in NS3 and 24, 28, 30, 31, 58, 92, and 93 in NS5A.

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; IL28B, interleukin 28.

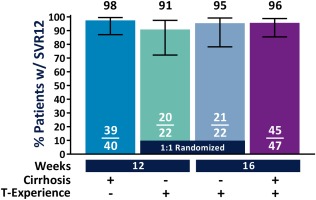

EFFICACY

In nonrandomized patients with cirrhosis, treatment‐naive patients treated for 12 weeks had an SVR12 rate of 98% (39/40, 95% CI 87‐99), with no virologic failures (one patient had missing SVR12 data due to being lost to follow‐up but did achieve SVR4), and those with prior treatment experience had an SVR12 rate of 96% (45/47; 95% CI 86‐99) after 16 weeks of G/P treatment (Fig. 2). Treatment‐experienced patients without cirrhosis received either 12 or 16 weeks of G/P treatment; the SVR12 rates were 91% (20/22; 95% CI 72‐97) and 95% (21/22; 95% CI 78‐99), respectively; within this population, the difference in SVR12 for patients receiving 12 and 16 weeks of treatment was –4.5% (95% CI –23.6 to 13.9) with two relapses and one relapse in each arm, respectively. One treatment‐experienced patient with cirrhosis (16‐week arm) had virologic breakthrough; this patient had study drug exposures >50% lower than average at most study visits, with suspected noncompliance. Among all patients with virologic failure, treatment‐emergent substitutions detected at the time of failure included Y56H, A156G, or Q168R in NS3 and A30K, L31F, or Y93H in NS5A (Table 2). On‐treatment response at weeks 4, 8, 12, and 16 (as applicable) are shown in Supporting Table S2.

Figure 2.

The numbers and percentages of patients who achieved SVR12 in each treatment arm are summarized. Treatment‐naive patients with compensated cirrhosis were treated with G/P for 12 weeks, and patients with both compensated cirrhosis and prior treatment experience were treated for 16 weeks. Patients without cirrhosis who had prior treatment experience were randomized 1:1 to receive either 12 or 16 weeks of G/P. Two‐sided 95% CIs were calculated using the Wilson score method for binomial proportions. Abbreviation: TE, treatment.

Table 2.

Patients with Virologic Failure: NS3 and NS5A Variants at Baseline and Time of Failure

| NS3 Variants | NS5A Variants | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Treatment Duration | Prior HCV Treatment | Cirrhosis; Fibrosis | Baseline HCV RNA (IU/mL) | Failure | Baseline | At Failure | Baseline | At Failure |

| 12 weeks | pegIFN/RBV | No; F0‐F1 | 8,140,000 | Relapse | None | None | Y93H | Y93H |

| 12 weeks | pegIFN/RBV | No; F2 | 15,700,000 | Relapse | None | None | A30K | A30K+Y93H |

| 16 weeks | pegIFN/RBV | No; F0‐F1 | 18,900,000 | Relapse | None | Y56H+Q168R | A30K | A30K+Y93H |

| 16 weeks | SOF/RBV | Yes; F4 | 2,840,000 | Relapse | None | None | None | L31F+Y93H |

| 16 weeks | pegIFN/RBV | Yes; F4 | 17,400,000 | Breakthrough | A166S | A156G+A166S | None | A30K+Y93H |

Variants were present in ≥15% of viral population as detected by next‐generation sequencing; variants assessed at NS3 positions 36, 43, 54, 55, 56, 80, 155, 156, 166, and 168 and NS5A positions 24, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 58, 92, and 93.

Patients with prior SOF‐based treatment experience had a 98% (41/42; 95% CI 88‐99) SVR12 rate. Patients with compensated cirrhosis had an SVR12 rate of 97% (84/87; 95% CI 90‐99) compared to 93% (41/44; 95% CI 82‐98) for those without cirrhosis (Table 3). Additionally, the SVR12 rates in those without and those with baseline NS3 polymorphisms were 96% (105/109; 95% CI 91‐99) and 95% (18/19; 95% CI 75‐99), respectively. Among all patients with cirrhosis (including those with prior treatment experience), the SVR12 rates in those without and those with baseline NS5A polymorphisms were 97% (68/70; 95% CI 90‐99) and 100% (15/15; 95% CI 80‐100), respectively. Among treatment‐experienced patients without cirrhosis, the SVR12 rate in those without NS5A polymorphisms was 100% (34/34; 95% CI 90‐100); for those with NS5A polymorphisms treated for 12 weeks or 16 weeks, 4/6 and 2/3 achieved SVR12, respectively (Supporting Table S3). Across all patients, baseline NS5A polymorphisms A30K/M/R/S/T/V and Y93H were the most frequent, detected in 12 (9.3%, 2 with A30K) and 8 (6%) patients, respectively (Supporting Table S4). Seven of 8 patients with Y93H in NS5A achieved SVR12 (Supporting Table S3). In addition, 10 of 12 patients with polymorphisms at NS5A amino acid position 30 achieved SVR12.

Table 3.

SVR12 Rates for Key Patient Subgroups

| Patient Subgroup | n/N | SVR12 (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|

| Treatment duration | ||

| 12 weeks | 59/62 | 95% (87‐98) |

| 16 weeks | 66/69 | 96% (88‐99) |

| Prior HCV treatment | ||

| Naive | 39/40 | 98% (87‐99) |

| Any experience | 86/91 | 95% (88‐98) |

| SOF‐based | 41/42 | 98% (88‐99) |

| Compensated cirrhosis | ||

| With | 84/87 | 97% (90‐99) |

| Without | 41/44 | 93% (82‐98) |

SAFETY, AEs, AND LABORATORY ABNORMALITIES

The majority of AEs were classified as mild, and no patients prematurely discontinued study drug due to AEs (Table 4). Fatigue and headache were the only AEs reported in >10% of total patients across both treatment arms, at 22% and 19%, respectively. Six serious AEs were reported; none were attributed to study drugs by investigators, and none of the patients discontinued study drug (Supporting Table S5). The type and frequency of AEs appeared similar between 12‐week and 16‐week durations of G/P treatment. No hepatic decompensation events were observed.

Table 4.

AEs and Key Laboratory Abnormalities

| Arm A (12 Weeks G/P) | Arm B (16 Weeks G/P) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1:1 Randomized | ||||

| Event, n (%) | Treatment‐Naive With Cirrhosis (n = 40) | Treatment‐Experienced Without Cirrhosis (n = 22) | Treatment‐experienced Without Cirrhosis (n = 22) | Treatment‐Experienced With Cirrhosis (n = 47) |

| Any AE | 32 (80) | 12 (55) | 17 (77) | 34 (72) |

| Serious AE | 1 (3) | 1 (5) | 1 (5) | 3 (6) |

| Serious AE related to study drugs | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| AE leading to study drug d/c | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| AEs occurring in ≥ 10% of patients | ||||

| Fatigue | 5 (13) | 4 (18) | 4 (18) | 16 (34) |

| Headache | 10 (25) | 5 (23) | 4 (18) | 6 (13) |

| Key laboratory abnormalities,a n (%) | ||||

| ALTb | ||||

| Grade ≥ 3 (>5 × ULN) | 0 | 2 (9) | 0 | 0 |

| Total bilirubin | ||||

| Grade ≥ 3 (>3 × ULN) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (2) |

Laboratory abnormalities based on the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events, version 4.

ALT must have been increased post nadir in grade.

Abbreviations: d/c, discontinuation; ULN, upper limit of normal.

No patients experienced clinically significant ALT elevations. Two treatment‐experienced patients without cirrhosis (12‐week treatment arm) and with baseline elevated ALT (one had grade 2 and one grade 3 ALT levels at baseline) had post‐nadir grade 3 increases in ALT (from a previous grade 2) within the first 8 days of treatment; this is consistent with the expected physiologic range of fluctuation in patients with high baseline ALT levels. The ALT elevations were not associated with bilirubin elevations or AEs and thereafter steadily decreased without intervention or interruption of study drug. Both patients completed treatment and had SVR12. One patient with baseline elevated grade 2 bilirubin had sporadic increases in total bilirubin with indirect predominance to grade 3 at treatment weeks 1, 12, and 16, without concomitant ALT elevations. This patient completed treatment without interruption and had SVR12.

Discussion

The patient population treated with G/P in Part 3 of SURVEYOR‐II included some of the most difficult‐to‐treat patients with HCV infection, incorporating many current and historic negative predictors of response to HCV therapy; the treated population, including patients with HCV genotype 3, compensated cirrhosis, and prior treatment experience (including treatment with SOF‐based regimens), was the largest such patient group to date.10, 11, 14 Among patients with GT3 infection and compensated cirrhosis, treatment with 12 and 16 weeks of RBV‐free G/P yielded high rates of SVR12 in treatment‐naive and treatment‐experienced patients, respectively. Additionally, the regimen was well tolerated with no serious AEs related to study drug and no AEs leading to study drug discontinuation.

Treatment options for patients with HCV GT3 infection and compensated cirrhosis and/or prior treatment experience are currently limited and often require testing for baseline polymorphisms and/or coadministration of RBV or treatment duration of 24 weeks to maximize SVR12 rates. Due to higher rates of relapse observed with SOF/VEL treatment in GT3‐infected patients with NS5A polymorphisms, particularly those with Y93H (20% [3/15] relapse rate22), pretreatment testing for the presence of Y93H is recommended when using this regimen for patients with treatment experience and/or cirrhosis.12, 13 Coadministration of RBV with SOF/VEL is recommended: if a patient has prior SOF‐containing therapy experience, if Y93H is present upon testing,12, 13 or regardless of baseline polymorphism testing for patients with both treatment experience and cirrhosis.12 Similarly, among GT3‐infected patients with treatment experience and/or cirrhosis, RBV coadministration is recommended when using the combination of SOF plus DCV in patients with baseline Y93H or regardless of baseline polymorphism testing for patients with both prior treatment experience and compensated cirrhosis. Extended 24‐week treatment duration of SOF/DCV is also recommended for all patients with cirrhosis.10, 11 In vitro, the Y93H polymorphism results in a >100‐fold reduction in VEL susceptibility and a >3,700‐fold reduction in DCV susceptibility.22, 23 Similarly, susceptibility to VEL and DCV is reduced by 16‐fold and 117‐fold, respectively, in the presence of A30K.23 In contrast, these single A30K or Y93H polymorphisms confer minimal changes to in vitro PIB susceptibility (<2.5‐fold each).17, 18

In this study, treatment with G/P for 12 and 16 weeks achieved 95% or greater rates of SVR12 in treatment‐naive and treatment‐experienced patients, respectively. While treatment‐naive and treatment‐experienced patients with cirrhosis were treated for 12 weeks and 16 weeks, respectively, treatment‐experienced patients without cirrhosis were randomized to either 12 or 16 weeks of G/P treatment, achieving SVR12 rates of 91% (20/22) and 95% (21/22), respectively. The difference in SVR12 rate between 12 and 16 weeks of treatment was driven by a single additional relapse in the 12‐week arm, making it difficult to determine the optimal treatment duration for this population based on these results alone. However, results from prior phase 2 studies in treatment‐experienced GT3‐infected patients without cirrhosis treated for 12 weeks demonstrated a similar tendency toward lower efficacy, with an SVR12 rate of 89% (24/27) with two relapses.21 Notably, the 16‐week regimen of G/P is now approved by the US Food and Drug Administration and the European Medicines Agency for the treatment of GT3‐infected patients with prior treatment experience (with or without cirrhosis), supported by data from prior phase 2 studies and this phase 3 study, demonstrating an overall 96% (66/69) SVR12 rate in this subpopulation.20

Among patients with baseline NS5A polymorphisms and compensated cirrhosis (n = 15, including 5 with Y93H at baseline), all achieved SVR12. Among treatment‐experienced patients without cirrhosis, 3 had Y93H at baseline and 2/3 (67%) achieved SVR12; both patients with A30K at baseline had virologic failure. With a limited sample size available and the low prevalence of these polymorphisms in this NS5A inhibitor–naive population, it is difficult to determine the true impact of such polymorphisms on treatment outcome. Prior studies have also reported low prevalence of both the Y93H (8.3%‐8.8%11, 24) and A30K (4.5%‐6%24, 25) polymorphisms in patients with HCV genotype 3. Moreover, as discussed, neither of these polymorphisms has a significant impact on in vitro susceptibility to PIB.18 In support of these data, per the US Food and Drug Administration and European Medicines Agency product use labels, GT3‐infected patients with compensated cirrhosis and/or prior treatment experience do not require viral resistance testing prior to treatment with G/P.20

Altogether, the efficacy results from this study demonstrate that G/P is an all‐oral DAA regimen with high cure rates that does not require RBV coadministration in HCV GT3‐infected patients, regardless of other traditional negative predictors of response such as prior treatment experience or compensated cirrhosis. Retreatment of patients who had virologic failure to G/P therapy may require a regimen with more than two mechanisms of action, such as G/P plus SOF, which is a DAA combination currently being evaluated in an ongoing clinical study (registered clinical trial: NCT02939989).

Treatment with G/P was safe and well tolerated, regardless of treatment duration or baseline patient characteristics. Previous‐generation NS3/4A protease inhibitor–containing regimens have been associated with AEs, including severe rash, marked hyperbilirubinemia, neutropenia, anemia, and elevated ALT, particularly in patients with cirrhosis.26 However, all of these events were absent or rarely observed in SURVEYOR‐II Part 3, even in patients with compensated cirrhosis. No patients discontinued or interrupted study drugs due to AEs. Moreover, there were no incidences of drug‐induced liver injury or hepatic decompensation. Overall, the safety profile of patients with compensated cirrhosis was similar to that of those without cirrhosis. Serious AEs reported in this study were uncommon (n = 6), and none were deemed related to study drugs. The most commonly reported AEs were fatigue and headache, and they were reported at rates similar to placebo control groups in other clinical trials.27, 28

A potential limitation of this study was the relatively low patient number within individual subpopulations (e.g., treatment‐experienced patients without cirrhosis). However, these patient numbers are not inconsistent with other studies within similar subpopulations.11, 14 Moreover, the largest cohort was patients with both treatment experience and cirrhosis (n = 47), with a sample size larger than evaluated in other studies; an SVR12 rate of 96% was observed in this more difficult‐to‐cure population after 16 weeks of G/P treatment. Finally, GT3‐infected patients with prior exposure to NS5A inhibitor–containing regimens were not studied here; thus, the impact of treatment‐emergent NS5A resistance–associated substitutions on the efficacy of G/P in this patient subpopulation is currently unknown.

In summary, SURVEYOR‐II Part 3 enrolled and treated some of the most difficult‐to‐cure HCV patients: those with GT3 infection and prior treatment experience and/or cirrhosis. Overall, the fixed‐dose combination of once‐daily RBV‐free G/P was well tolerated and demonstrated high SVR12 rates (≥95%) in treatment‐naive patients with cirrhosis treated for 12 weeks and treatment‐experienced patients with or without cirrhosis treated for 16 weeks. Therefore, G/P provides an efficacious and well‐tolerated once‐daily RBV‐free treatment option for patients with HCV genotype 3 and prior treatment experience and/or cirrhosis.

Supporting information

Additional Supporting Information may be found at onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/hep.29541/suppinfo

Supporting Information

Acknowledgment

AbbVie and the authors would like to express their gratitude to the patients who participated in this study and their families. They also thank all of the participating study investigators and coordinators, particularly Nela Hayes, of AbbVie. Medical writing was provided by Ryan J. Bourgo, Ph.D., of AbbVie.

Potential conflict of interest: Dr. Wyles consults for and received grants from AbbVie, Gilead, and Merck. Dr. Felizarta is on the speakers’ bureau of and received grants from AbbVie, Gilead, Janssen, and Merck. Dr. Agarwal consults for, advises, is on the speakers’ bureau of, and received grants from AbbVie. He consults for, advises, and is on the speakers’ bureau of Merck. He consults for, is on the speakers’ bureau of, and received grants from Gilead. Dr. Kwo advises and received grants from AbbVie, Bristol‐Myers Squibb, Gilead, and Merck. He advises Abbott, CVS, and Quest. Dr. Alric consults for, is on the speakers’ bureau of, and received grants from MSD, Gilead, AbbVie, and Bristol‐Myers Squibb. He received grants from Roche and Janssen. Dr. Lee consults for, advises, is on the speakers’ bureau of, and received grants from AbbVie, Bristol‐Myers Squibb, Gilead, and Merck. He consults for, is on the speakers’ bureau of, and received grants from Janssen. He consults for and received grants from Roche. He is on the speakers’ bureau of Pendopharm. Dr. Hassanein is on the speakers’ bureau of and received grants from AbbVie. Dr. Lin is employed by and owns stock in AbbVie. Dr. Lovell is employed by and owns stock in AbbVie. Dr. Liu is employed by and owns stock in AbbVie. Dr. Pilot‐Matias is employed by and owns stock in AbbVie. Dr. Kort is employed by and owns stock in AbbVie. Dr. Mensa is employed by and owns stock in AbbVie. Dr. Krishnan is employed by AbbVie.

Supported by AbbVie (NCT02243293).

REFERENCES

- 1. Adinolfi LE, Gambardella M, Andreana A, Tripodi MF, Utili R, Ruggiero G. Steatosis accelerates the progression of liver damage of chronic hepatitis C patients and correlates with specific HCV genotype and visceral obesity. Hepatology 2001;33:1358‐1364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Fartoux L, Poujol‐Robert A, Guechot J, Wendum D, Poupon R, Serfaty L. Insulin resistance is a cause of steatosis and fibrosis progression in chronic hepatitis C. Gut 2005;54:1003‐1008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Leandro G, Mangia A, Hui J, Fabris P, Rubbia‐Brandt L, Colloredo G, et al. Relationship between steatosis, inflammation, and fibrosis in chronic hepatitis C: a meta‐analysis of individual patient data. Gastroenterology 2006;130:1636‐1642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Asselah T, Rubbia‐Brandt L, Marcellin P, Negro F. Steatosis in chronic hepatitis C: why does it really matter? Gut 2006;55:123‐130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Kumar D, Farrell GC, Fung C, George J. Hepatitis C virus genotype 3 is cytopathic to hepatocytes: reversal of hepatic steatosis after sustained therapeutic response. Hepatology 2002;36:1266‐1272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Rubbia‐Brandt L, Quadri R, Abid K, Giostra E, Male PJ, Mentha G, et al. Hepatocyte steatosis is a cytopathic effect of hepatitis C virus genotype 3. J Hepatol 2000;33:106‐115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Bochud PY, Cai T, Overbeck K, Bochud M, Dufour JF, Mullhaupt B, et al. Genotype 3 is associated with accelerated fibrosis progression in chronic hepatitis C. J Hepatol 2009;51:655‐666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. De Nicola S, Aghemo A, Rumi MG, Colombo M. HCV genotype 3: an independent predictor of fibrosis progression in chronic hepatitis C. J Hepatol 2009;51:964‐966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Nkontchou G, Ziol M, Aout M, Lhabadie M, Baazia Y, Mahmoudi A, et al. HCV genotype 3 is associated with a higher hepatocellular carcinoma incidence in patients with ongoing viral C cirrhosis. J Viral Hepat 2011;18:e516‐e522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Nelson DR, Cooper JN, Lalezari JP, Lawitz E, Pockros PJ, Gitlin N, et al. All‐oral 12‐week treatment with daclatasvir plus sofosbuvir in patients with hepatitis C virus genotype 3 infection: ALLY‐3 phase III study. Hepatology 2015;61:1127‐1135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Leroy V, Angus P, Bronowicki JP, Dore GJ, Hezode C, Pianko S, et al. Daclatasvir, sofosbuvir, and ribavirin for hepatitis C virus genotype 3 and advanced liver disease: a randomized phase III study (ALLY‐3+). Hepatology 2016;63:1430‐1441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases , Infectious Diseases Society of America. HCV guidance: recommendations for testing, managing, and treating hepatitis C. https://www.hcvguidelines.org/sites/default/files/full-guidance-pdf/HCVGuidance_September_21_2017_e.pdf. Published September 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 13. European Association for the Study of the Liver . EASL recommendations on treatment of hepatitis C 2016. J Hepatol 2017;66:153‐194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Foster GR, Afdhal N, Roberts SK, Brau N, Gane EJ, Pianko S, et al. Sofosbuvir and velpatasvir for HCV genotype 2 and 3 infection. N Engl J Med 2015;373:2608‐2617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Pianko S, Flamm SL, Shiffman ML, Kumar S, Strasser SI, Dore GJ, et al. Sofosbuvir plus velpatasvir combination therapy for treatment‐experienced patients with genotype 1 or 3 hepatitis C virus infection: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med 2015;163:809‐817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Ng T, Reisch T, Middleton T, McDaniel K, Kempf D, Lu L, et al. ABT‐493, a potent HCV NS3/4A protease inhibitor with broad genotypic coverage [Abstract]. In: 21st Annual Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections; March 3‐6, 2014; Boston, MA. Abstract 636.

- 17. Ng T, Pilot‐Matias T, Tripathi R, Schnell G, Reisch T, Beyer J, et al. Analysis of HCV genotype 2 and 3 variants in patients treated with combination therapy of next generation HCV direct‐acting antiviral agents ABT‐493 and ABT‐530 [Abstract]. In: The International Liver Conference; April 13‐17, 2016; Barcelona, Spain; 2016. Abstract 430.

- 18. Ng TI, Krishnan P, Pilot‐Matias T, Kati W, Schnell G, Beyer J, et al. In vitro. antiviral activity and resistance profile of the next generation hepatitis C virus NS5A inhibitor pibrentasvir. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2017;61:e02558‐16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Kosloski MP, Dutta S, Zhao W, Pugatch D, Mensa F, Kort J, et al. Pharmacokinetics, safety, and tolerability of next generation direct‐acting antivirals ABT‐493 and ABT‐530 in subjects with renal impairment [Abstract]. In: The International Liver Conference; April 13‐17, 2016; Barcelona, Spain. Abstract THU‐230.

- 20.Mavyret (glecaprevir and pibrentasvir tablets) [US package insert]. North Chicago, IL: AbbVie; 2017.

- 21. Kwo PY, Poordad F, Asatryan A, Wang S, Wyles DL, Hassanein T, et al. Glecaprevir and pibrentasvir yield high response rates in patients with HCV genotype 1‐6 without cirrhosis. J Hepatol 2017;67:263‐271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Epclusa (sofosbuvir and velpatasvir) [package insert]. Foster City, CA: Gilead Sciences; 2016.

- 23.Daklinza (daclatasvir) [package insert]. Princeton, NJ: Bristol‐Meyers Squibb; 2016.

- 24. Hernandez D, Zhou N, Ueland J, Monikowski A, McPhee F. Natural prevalence of NS5A polymorphisms in subjects infected with hepatitis C virus genotype 3 and their effects on the antiviral activity of NS5A inhibitors. J Clin Virol 2013;57:13‐18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Walker A, Siemann H, Groten S, Ross RS, Scherbaum N, Timm J. Natural prevalence of resistance‐associated variants in hepatitis C virus NS5A in genotype 3a–infected people who inject drugs in Germany. J Clin Virol 2015;70:43‐45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Banerjee D, Reddy KR. Review article: safety and tolerability of direct‐acting anti‐viral agents in the new era of hepatitis C therapy. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2016;43:674‐696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Feld JJ, Jacobson IM, Hezode C, Asselah T, Ruane PJ, Gruener N, et al. Sofosbuvir and velpatasvir for HCV genotype 1, 2, 4, 5, and 6 infection. N Engl J Med 2015;373:2599‐2607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Kowdley KV, Colombo M, Zadeikis N, Mantry P, Calinas F, Aguilar H, et al. ENDURANCE‐2: safety and efficacy of glecaprevir/pibrentasvir in hepatitis C virus genotype 2‐infected patients without cirrhosis: a randomized, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled study [Abstract]. In: The Liver Meeting; November 11‐15, 2016; Boston, MA; 2016. Abstract 73.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional Supporting Information may be found at onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/hep.29541/suppinfo

Supporting Information