This survey study uses clinical data from a set of self-administered, self-graded questionnaires to examine the correlation among resilience, depression, and health-related quality of life for patients with hidradenitis suppurativa.

Key Points

Question

What is the association of resilience with depression and quality of life for patients with hidradenitis suppurativa?

Findings

In this cross-sectional, multicenter survey study involving 154 patients with hidradenitis suppurativa, higher levels of resilience statistically significantly modified the association of depression with quality of life.

Meaning

In the management and treatment of patients with hidradenitis suppurativa, methods to increase resilience may improve health-related quality of life.

Abstract

Importance

Hidradenitis suppurativa (HS) places a significant burden on the health-related quality of life (HRQOL) of patients, many of whom have depression. Resilience can play a role in mitigating the negative stressors, such as the symptoms of HS, on patients’ mental health.

Objective

To investigate the correlation among resilience, depression, and HRQOL for patients with HS.

Design, Setting, and Participants

This cross-sectional survey study of 154 patients from 2 referral centers in the United States and in Denmark was conducted from June 1, 2016, to March 31, 2017. Patients were considered eligible if they were 18 years or older and had a visit for HS at 1 of the 2 referral centers in the past 2 years (from January 1, 2014, through December 31, 2016). Patients were excluded if they declined to participate, could not read or write in English or Danish, or had a cognitive disability that would preclude their understanding of the survey questions.

Main Outcomes and Measures

The survey instrument included 4 questionnaires: (1) a sociodemographic and clinical characteristics questionnaire, (2) the Brief Resilient Coping Scale, (3) the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale, and (4) the Dermatology Life Quality Index. The main outcome of interest was the HRQOL as measured by the Dermatology Life Quality Index.

Results

All 154 patients submitted a completed survey. The mean (SD) age of the participants was 40.93 (13.5) years; most participants were women (130 [84.4%]), and most participants self-identified as white (139 [90.2%]). The rate of depression among the patients in this study was comparable to those reported in previous studies; 55 patients (35.7%) were classified as having depression, and 32 patients (20.8%) had borderline depressive symptoms. Patient-rated HS severity and the depression score each independently estimated 27% and 10% of variation in HRQOL, respectively. The interaction term for resilience and depression was significant, indicating that resilience moderates depression. Analysis of the mediation effects of resilience was not significant, indicating that resilience did not mediate the association between depressive symptoms and HRQOL. The resilience score was significantly associated with depressive symptoms (regression coefficient a = −0.21; P < .001), and the depressive symptoms score (c = 0.637; P < .001) was significantly associated with lower HRQOL (c′ = 0.644; P < .001). However, both the direct association (b = 0.033; P = .86) and the indirect association (a × b = 0.007; P = .87) of resilience with HRQOL were not significant.

Conclusions and Relevance

Patients with higher resilience levels experienced a smaller decrease in HRQOL as depressive symptoms increased. Because the findings suggest that resilience can be taught, there is an opportunity to develop a resiliency training program and investigate its role in stress levels and depressive symptoms, as well as in HRQOL and disease activity.

Introduction

Hidradenitis suppurativa (HS) is a chronic, inflammatory skin disease of unknown etiology that causes sudden and persistent eruptions of painful swollen nodules and draining abscesses with disfiguring scars of the skin folds. This condition can make walking, sitting, and working difficult or impossible, and its malodorous drainage is humiliating and uncomfortable. Thus, HS negatively affects patients’ health-related quality of life (HRQOL), and approximately half of patients with HS have a psychiatric comorbidity, most commonly depression.

The association between depression and HS is speculated to be psychosocial or physiological because inflammatory proteins have been associated with symptoms of depression. Specifically, elevated interleukin 6 (IL-6) and IL-8 levels in plasma, serum, and cerebrospinal fluid, as well as epidermal growth factor, have been associated with depression. The levels of all 3 of these cytokines can be elevated in patients with HS. More research is needed to understand the pathomechanism of HS and depression, but a strong association remains between depression and worsening health, as has been shown in patients with chronic kidney disease, hypertension, or heart disease. Importantly, a recent study showed that resilience can moderate the association between depression and HRQOL for patients with cardiac disease.

Resilience refers to the ability to successfully adapt to stress and adversity. Windle(p163) defined resilience as the “process of effectively negotiating, adapting to, or managing significant sources of stress or trauma.” Resilience has been shown to play a role in mitigating the stressors, such as HS symptoms, contributing to depression. In addition, resilience scores and depression scores have been shown to be inversely related. Thus, given the high prevalence of depression and the adverse association of depression with health, there is a need to investigate if resilience mediates or modifies the correlation between depressive symptoms and HRQOL for patients with HS.

Methods

This international, multicenter, cross-sectional survey study was conducted from June 1, 2016, to March 31, 2017. Two referral sites—Penn State Health Milton S. Hershey Medical Center in Hershey, Pennsylvania, and Zealand University Hospital in Roskilde, Denmark—coordinated to develop an instrument to survey their patients with HS. The instrument included 4 questionnaires: a sociodemographic and clinical characteristics questionnaire, the Brief Resilient Coping Scale (BRCS) (score range: 4-20, with the highest score indicating high resilience), the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) (score range: 0-21, with a subscore of 11 or greater indicating depression), and the Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI) (score range: 0-30, with lower scores typically indicating lower HRQOL). The instrument was built into an online data-collection tool called REDCap. This study was approved by the ethical review boards of the Penn State Health Milton S. Hershey Medical Center and Zealand University Hospital. Implied consent was obtained in the United States. With implied consent, participants read a description of the research, and if they go on to complete any part of the survey, then it is implied that they consented (because they went on to complete the survey); in this form of consent, a consent form is not signed. This also differs from verbal consent because the participant and investigator are never in the same room because the survey was electronic. Written informed consent was obtained in Denmark.

Patients were eligible for inclusion if they were 18 years or older and had a visit for HS at 1 of the referral centers in the past 2 years (from January 1, 2014, through December 31, 2016). Patients were excluded if they declined to participate, could not read or write in English or Danish, or had a cognitive disability that would preclude their understanding of the survey questions. Only patients who submitted a complete survey were included (n = 154); thus, methods for handling missing data were not required.

Measures

Health-Related Quality of Life

The HRQOL of the participants was the outcome of interest or dependent variable in this study. It was assessed using the DLQI, a widely used, validated, skin-specific HRQOL questionnaire comprising 10 items related to symptoms, embarrassment, shopping and home care, clothing, social and leisure activities, work or study, close relationships, sex, and treatment. Each DLQI question asks patients to score the influence of HS on their life over the previous week, and scores range from 0 to 30 points. To facilitate our interpretation, we reverse coded the scores in such a way that lower scores indicated lower HRQOL in the analysis. The score categories were as follows: 29 to 30 points indicate no influence on HRQOL, 25 to 28 points indicate a small influence, 20 to 24 points indicate a moderate influence, 10 to 19 points indicate a very large influence, and 0 to 9 points indicate an extremely large influence. The DLQI in this current sample had a Cronbach α = .90.

Depressive Symptoms

Depressive symptoms of the participants were assessed using the HADS. The HADS is a widely used, validated, 14-item self-assessment of the current anxiety and depressive symptoms of patients. There are 7 independent subscales for anxiety and 7 independent subscales for depression, and scores range from 0 to 21 points. Subscores of 11 points or greater in the depression subscale were interpreted as having depression. A score of 8 to 10 points was considered a borderline case. In this analysis, only cases were included. The HADS in this sample had a Cronbach α = .88.

Resilience

Resilience of the participants was assessed using the BRCS. The BRCS questionnaire has 4 items, and scores range from 4 to 20 points. Scores of 4 to 13 were considered low resilience, 14 to 16 were considered moderate, and 17 to 20 were considered high resilience. The BRCS in the current sample had a Cronbach α = .74.

Sociodemographic and Clinical Characteristics

Patients were asked to provide sociodemographic data—age, sex, race/ethnicity, study site, and educational attainment (coded as 1, less than high school diploma; 2, high school diploma or general education development [GED] certificate; 3, some vocational school; 4, associate’s degree or some college; 5, bachelor’s degree; or 6, graduate degree). In addition, patients self-reported their HS severity at the time of the survey using an 11-point scale ranging from 0 (not severe) to 10 (very severe).

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive analyses were performed to describe the characteristics of the study sample. Continuous variables are presented as mean (SD) values, and categorical variables are presented as frequencies and percentages. Continuous variables were centered on the mean of each variable to facilitate interpretation. Next, a series of multiple regressions, which require basic assumptions of linearity, independence, normal distribution, and equal variance, were conducted to determine the squared semipartial correlation of each independent variable, and these correlations were ranked. The Akaike information criterion was used as an estimate of the quality of the regression models, with a lower number indicating better quality. The mediating influence, partial or complete, of resilience on the association between depression and HRQOL was tested using the product of coefficients approach or the Sobel test. The moderating influence of resilience on the association between depression and HRQOL was examined by adding and testing the interaction term in the regression model. A significant interaction term would indicate that resilience moderates the association between depression and HRQOL. To further evaluate the moderating influences, simple slopes were calculated, and significance testing was performed. The Johnson-Neyman technique was used to calculate the values of the moderator for which regression of the dependent variable on the independent variable was significant. Assumptions of linearity, independence, and equal and normal residual variance were evaluated. Points with a Cook distance greater than 0.04 were excluded as outliers. Statistical significance was determined by an α level of .05 (2-sided P = .05). Analyses were performed using R, version 3.3.2 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing).

A power calculation was performed with a sample of 154 participants, a conservative medium effect size of 0.10 (α = .05), in a multiple linear regression model with 8 predictors. This calculation showed the power of 79%.

Results

In the United States, 96 patients from the referral centers were invited to participate, 69 (71.8%) of whom responded and 58 (60.4%) of whom submitted complete data. In Denmark, the survey was offered to all patients with HS who visited a specialty clinic for HS. The response rate cannot be calculated, however, because the number of people who viewed and decided not to participate in the survey is unknown. Overall, in Denmark, 126 patients participated, and 96 (76.1%) provided complete data. The final sample for the study, including patients from the US and Denmark sites, was 154 participants who submitted complete data. The mean (SD) age of the participants was 40.9 (13.5) years; most participants were women (130 [84.4%], and most participants self-identified as white (139 [90.2%]). Table 1 lists the characteristics of the study sample.

Table 1. Characteristics of the Study Sample.

| Characteristic | Total, No. (%) | No. (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Denmark Site | US Site | ||

| All participants | 154 (100) | 96 (62.3) | 58 (37.7) |

| Age, mean (SD), y | 40.9 (13.5) | 41.6 (13.6) | 39.8 (13.3) |

| Scores on scales | |||

| Depressive symptoms, mean (SD) | 8.6 (4.8) | 8.1 (4.6) | 9.7 (4.8) |

| Depression | 55 (35.7) | 30 (31.3) | 25 (43.1) |

| Borderline depression | 32 (20.8) | 21 (21.9) | 11 (18.9) |

| Resilience, mean (SD) | 14.5 (2.7) | 14.7 (2.4) | 14.5 (2.9) |

| HRQOL, mean (SD)a | 10.1 (8.6) | 12.1 (8.9) | 9.2 (7.9) |

| Sex | |||

| Male | 24 (15.6) | 20 (20.8) | 4 (6.90) |

| Female | 130 (84.4) | 76 (79.2) | 54 (93.1) |

| Educational attainment | |||

| <High school | 14 (9.09) | 12 (12.5) | 2 (3.5) |

| High school diploma or GED certificate | 24 (15.6) | 9 (9.4) | 15 (25.9) |

| Vocational school | 19 (12.3) | 19 (19.8) | 0 |

| Some college or associate’s degree | 40 (25.9) | 19 (19.8) | 21 (36.2) |

| Bachelor’s degree | 42 (27.3) | 28 (29.2) | 14 (24.1) |

| Graduate degree | 15 (9.7) | 9 (9.4) | 6 (10.3) |

| Race/ethnicity | |||

| White | 139 (90.3) | 94 (97.9) | 45 (77.6) |

| Asian | 1 (0.65) | 1 (1.04) | 0 |

| Black | 9 (5.84) | 0 | 9 (15.5) |

| Hispanic or Latino | 3 (1.95) | 0 | 3 (5.2) |

| Other | 2 (1.30) | 1 (1.04) | 1 (1.7) |

Abbreviations: GED, general education development; HRQOL, health-related quality of life.

Scores were reverse coded; thus, lower scores indicated lower QOL; scores before reverse coding had a mean (SD) of 19.86 (8.62).

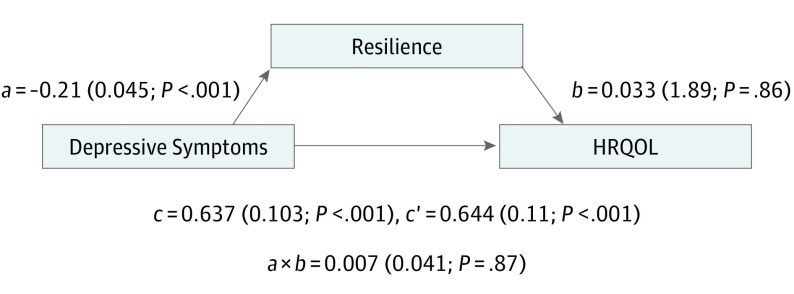

The independent variables with the highest semipartial correlations were HS severity and depression score, with HS activity independently estimating 27% and depressive symptoms estimating 10% of variation in HRQOL (Table 2). For the mediation analysis, resilience score was significantly associated with depressive symptoms score (regression coefficient a = −0.21; P < .001), and depressive symptoms score (c = 0.637; P < .001) was significantly associated with lower HRQOL (c′ = 0.644; P < .001). However, both the direct association (b = 0.033; P = .86) and the indirect association (a × b = 0.007; P = .87) of resilience on HRQOL were not significant. These findings indicate that resilience did not mediate the association between depressive symptoms and HRQOL (Figure 1).

Table 2. Model of Health-Related Quality of Life, With Ranked Semipartial Correlation of Independent Variables With Model Performance.

| Variable | ΔR2 | Rank | b (SE) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model Without Interaction | Model With Interaction | |||

| HS activity | −0.27 | 1 | −1.73 (0.46)a | −1.70 (0.47)a |

| Depressive symptoms | −0.10 | 2 | −0.64 (0.17)a | −0.66 (0.11)a |

| Race/ethnicity | −0.017 | 3 | NA | NA |

| Study site | −0.005 | 4 | NA | NA |

| Sex | −0.004 | 5 | NA | NA |

| Resilience | −0.004 | 5 | −0.03 (0.19) | −0.11 (0.19) |

| Education | −0.003 | 7 | NA | NA |

| Age | 0.001 | 8 | NA | NA |

| Depressive symptoms × resilience (interaction term) | NA | NA | NA | 0.07a |

| Full model r2 | 0.54 | NA | 0.56 | 0.58 |

| Full model adjusted R2 | 0.52 | NA | 0.55 | 0.56 |

| Full model AIC | 994.08 | NA | 957.72 | 955.28 |

Abbreviations; AIC, Akaike information criterion; b, regression coefficient; HRQOL, health-related quality of life; HS, hidradenitis suppurativa; NA, not applicable.

P < .05.

Figure 1. Mediation Analysis of the Association of Resilience With Depression and Health-Related Quality of Life (HRQOL).

The parameter estimates, b (SE; P value), are presented for the association of depressive symptoms with resilience (a = −0.21), the association of resilience with HRQOL after adjustment for depressive symptoms and hidradenitis suppurativa (HS) severity (b = 0.033), the association of depressive symptoms with HRQOL after adjustment for HS severity (c = 0.637), and the direct association between depressive symptoms with HRQOL after adjustment for resilience and HS severity (c′ = 0.644).

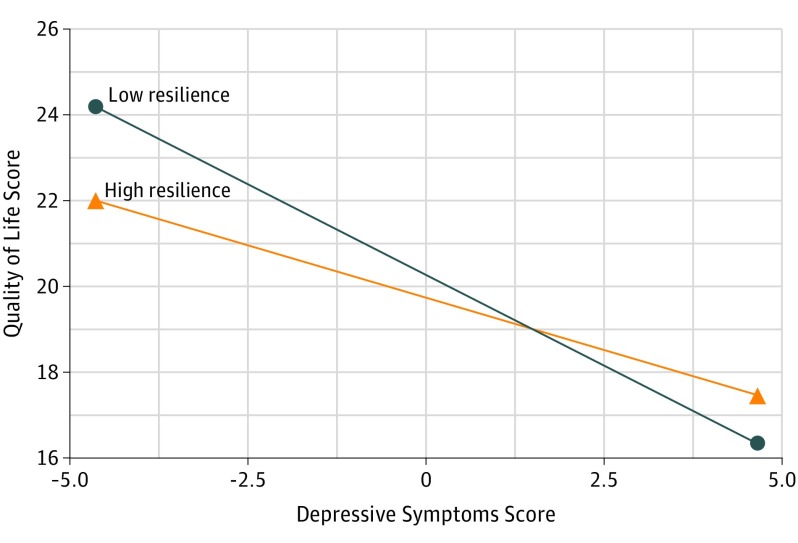

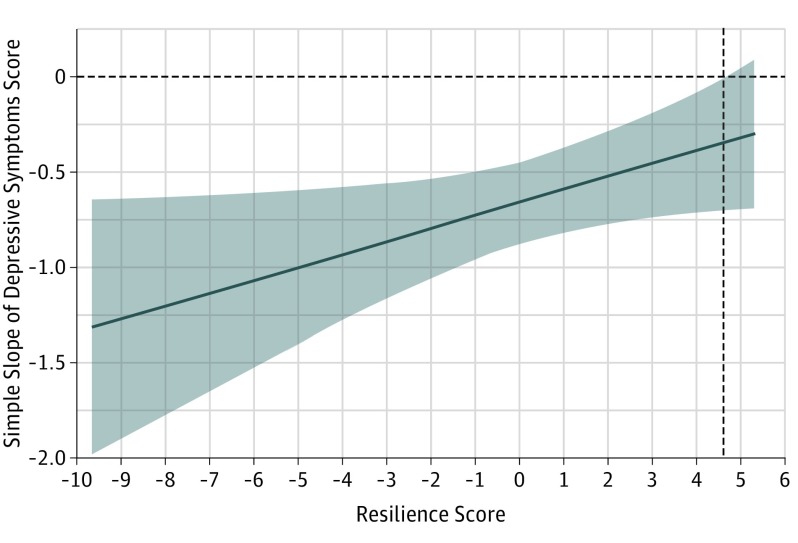

For the moderation analysis, HS severity and depression were included in the model along with the interaction term between depression score and resilience score on the basis of the a priori hypothesis of this study. This model estimated a 58% variation in HRQOL and had the lowest Akaike information criterion of the 3 models. The interaction term for resilience and depression was significant and supports the moderation of depression by resilience. The simple slope (SE) for higher levels of resilience (1.5 points above the mean) was 0.56 (0.02) with P < .001. The simple slope (SE) for lower levels of resilience (1.5 points below the mean) was 0.76 (0.02) with P < .001 (Figure 2). The moderation of resilience on the simple slope of depression was statistically significant for resilience scores below 19.13 on the BRCS, or 4.62 points above the mean as depicted in Figure 3.

Figure 2. Simple Slopes of the Moderation of Depressive Symptoms by Resilience on Health-Related Quality of Life (HRQOL).

Participants with low levels of resilience had a larger positive slope, indicating a larger decrease in HRQOL score for each unit increase in depressive symptoms score. In contrast, participants with high levels of resilience had a more shallow slope, indicating that as the depressive symptoms score increased, the decrease in HRQOL was lower. The areas of statistical significance of those where the 95% CIs (rectangular areas) do not overlap with 0 on the y-axis. Thus, only resilience levels higher than 4.62 points above the mean are not significant. Scores are centered on the mean.

Figure 3. Areas of Statistical Significance for Moderation of Resilience on Depression.

The Johnson-Neyman technique was used to determine the regions of significance for the moderation, for which the regression of the Dermatology Life Quality Index score on depression was significant. The shaded area is the 95% CI around the simple slope of depressive symptoms score. This shows that for participants with a resilience score less than 4.32 points above the mean, the simple slope of regression is significantly different from 0. In addition, resilience decreases the contribution of depression.

Discussion

Depression is a common comorbidity among patients with HS, and our findings support the hypothesis that resilience moderates depression in HS. Depression rates among the patients in this study were comparable to those reported in previous studies, suggesting that our findings have general relevance. Compared with healthy controls, patients with HS have been shown to have statistically significant higher rates of depression, which can contribute to impaired HRQOL. Overall, depression rates in the HS population vary in the literature, from as low as 5.9% to as high as 42.9% and 48.1%.

In the present study, 55 patients (35.7%) had HADS scores that were compatible with depression scores found in other studies, and 32 patients (20.7%) had borderline depressive symptoms that were similar to the published prevalence rates. Resilience can play an important role in mitigating the negative stressors, such as the symptoms of HS, on patients’ mental health. Without resilience, patients could develop depressive symptoms and even poor physical health as a result of these stressors. The results of this study indicate that an opportunity exists for an investigation into possible interventions for patients with low levels of resilience because they may be susceptible to depression.

Studies suggest that resilience is a modifiable construct and not a fixed trait in people. Thus, there is the potential for patients to learn resiliency, and research on resiliency training is growing. Current guidelines for the management of HS recommend adjuvant therapy, which may include a broad range of psychosocial support measures. Resilience training may be a useful form of adjuvant therapy in HS. A systematic review and meta-analysis of the efficacy of resilience training programs demonstrated that they led to improvement in resilience, nearly significant improvement in HRQOL, and decreases in depressive symptoms and stress levels. The resiliency training programs reviewed included online videos, self-guided books or readings, telephone calls with individuals or groups, in-person small group sessions with exercises and discussions, or a combination of these methods. These interventions aimed to enhance individuals’ sense of self-efficacy or agency to make a positive change in their condition, handle a variety of situations, and gain control of their lives. These aspects contribute to the well-being of dermatological patients and present an opportunity for further research into dermatological conditions, such as HS, in which resiliency may be relevant. In particular, investigations of the use of resiliency training programs to mitigate stress with symptoms of depression appear interesting because such programs may well improve HRQOL in both the short term and the long term.

Limitations

There are limitations to this study. First, the data were collected through a self-administered and self-reported survey. Second, disease activity was self-reported by patients, and no clinical measures for disease activity were used. Third, the sample size was limited to patients who provided complete data, leaving out those who skipped questions or submitted incomplete responses.

Conclusions

The results of this study support the hypothesis that resilience moderates depression in patients with HS. Participants with higher resilience scores experienced a smaller decrease in HRQOL as depressive symptoms increased. This finding may have clinical implications because resilience can be learned, and thus it presents an opportunity for patients to increase their resilience and for researchers to investigate new options for mitigating the burdens of HS. Adjuvant therapy is recommended by the current guidelines for managing HS; such therapy may include a broad range of psychosocial support measures. Resilience training may be a useful form of adjuvant therapy in HS.

References

- 1.Zouboulis CC, Bechara FG, Fritz K, et al. ; Deutsche Dermatologische Gesellschaft; Berufsverband Deutscher Dermatologen; Deutsche Gesellschaft fur Koloproktologie; Deutsche Gesellschaft fur Dermatochirugie; Hidradenitis Suppurativa Foundation; Deutsche Interessegemeinschaft Akne inversa; Deutsche Gesellschaft fur Psychosomatische Medizin; European Society of Dermatology and Psychiatry; European Society of Laser Dermatology . S1 guideline for the treatment of hidradenitis suppurativa/acne inversa* (number ICD-10 L73.2) [in German]. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2012;10(suppl 5):S1-S31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zouboulis CC, Del Marmol V, Mrowietz U, Prens EP, Tzellos T, Jemec GB. Hidradenitis suppurativa/acne inversa: criteria for diagnosis, severity assessment, classification and disease evaluation. Dermatology. 2015;231(2):184-190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.von der Werth JM, Jemec GB. Morbidity in patients with hidradenitis suppurativa. Br J Dermatol. 2001;144(4):809-813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wolkenstein P, Loundou A, Barrau K, Auquier P, Revuz J; Quality of Life Group of the French Society of Dermatology . Quality of life impairment in hidradenitis suppurativa: a study of 61 cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;56(4):621-623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Matusiak L, Bieniek A, Szepietowski JC. Psychophysical aspects of hidradenitis suppurativa. Acta Derm Venereol. 2010;90(3):264-268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Onderdijk AJ, van der Zee HH, Esmann S, et al. Depression in patients with hidradenitis suppurativa. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2013;27(4):473-478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dowlati Y, Herrmann N, Swardfager W, et al. A meta-analysis of cytokines in major depression. Biol Psychiatry. 2010;67(5):446-457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Remlinger-Molenda A, Wójciak P, Michalak M, Rybakowski J. Activity of selected cytokines in bipolar patients during manic and depressive episodes [in Polish]. Psychiatr Pol. 2012;46(4):599-611. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Memon AA, Sundquist K, Ahmad A, Wang X, Hedelius A, Sundquist J. Role of IL-8, CRP and epidermal growth factor in depression and anxiety patients treated with mindfulness-based therapy or cognitive behavioral therapy in primary health care. Psychiatry Res. 2017;254:311-316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bechara FG, Sand M, Skrygan M, Kreuter A, Altmeyer P, Gambichler T. Acne inversa: evaluating antimicrobial peptides and proteins. Ann Dermatol. 2012;24(4):393-397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Emelianov VU, Bechara FG, Gläser R, et al. Immunohistological pointers to a possible role for excessive cathelicidin (LL-37) expression by apocrine sweat glands in the pathogenesis of hidradenitis suppurativa/acne inversa. Br J Dermatol. 2012;166(5):1023-1034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fismen S, Ingvarsson G, Moseng D, Nathalie Dufour D, Jørgensen L. A clinical-pathological review of hidradenitis suppurativa: using immunohistochemistry one disease becomes two. APMIS. 2012;120(6):433-440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Marzano AV, Ceccherini I, Gattorno M, et al. Association of pyoderma gangrenosum, acne, and suppurative hidradenitis (PASH) shares genetic and cytokine profiles with other autoinflammatory diseases. Medicine (Baltimore). 2014;93(27):e187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nguyen HA, Anderson CAM, Miracle CM, Rifkin DE. The association between depression, perceived health status, and quality of life among individuals with chronic kidney disease: an analysis of the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2011-2012. Nephron. 2017;136(2):127-135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shao H, Mohammed MU, Thomas N, et al. Evaluating excessive burden of depression on health status and health care utilization among patients with hypertension in a nationally representative sample from the Medial Expenditure Panel Survey (MEPS 2012). J Nerv Ment Dis. 2017;205(5):397-404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Smolderen KG, Buchanan DM, Gosch K, et al. Depression treatment and 1-year mortality after acute myocardial infarction: insights from the TRIUMPH registry (Translational Research Investigating Underlying Disparities in Acute Myocardial Infarction Patients’ Health Status). Circulation. 2017;135(18):1681-1689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Liu JC, Chang LY, Wu SY, Tsai PS. Resilience mediates the relationship between depression and psychological health status in patients with heart failure: a cross-sectional study. Int J Nurs Stud. 2015;52(12):1846-1853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bonanno GA. Loss, trauma, and human resilience: have we underestimated the human capacity to thrive after extremely aversive events? Am Psychol. 2004;59(1):20-28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Windle G. What is resilience? a review and concept analysis. Rev Clin Gerontol. 2011;21(2):152-169. doi: 10.1017/S0959259810000420 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bitsaka V, Sharpley CF, Bell R. The buffering effect of resilience upon stress, anxiety, and depression in parents of a child with an autism spectrum disorder. J Dev Phys Disabil. 2013;25(5):533-543. doi: 10.1007/s10882-013-9333-5 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tan-Kristanto S, Kiropoulos LA. Resilience, self-efficacy, coping styles and depressive and anxiety symptoms in those newly diagnosed with multiple sclerosis. Psychol Health Med. 2015;20(6):635-645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Holden KB, Bradford LD, Hall SP, Belton AS. Prevalence and correlates of depressive symptoms and resiliency among African American women in a community-based primary health care center. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2013;24(4 suppl):79-93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, Conde JG. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)—a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform. 2009;42(2):377-381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Finlay AY, Khan GK. Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI)—a simple practical measure for routine clinical use. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1994;19(3):210-216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hongbo Y, Thomas CL, Harrison MA, Salek MS, Finlay AY. Translating the science of quality of life into practice: What do dermatology life quality index scores mean? J Invest Dermatol. 2005;125(4):659-664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Basra MK, Fenech R, Gatt RM, Salek MS, Finlay AY. The Dermatology Life Quality Index 1994-2007: a comprehensive review of validation data and clinical results. Br J Dermatol. 2008;159(5):997-1035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Snaith RP, Zigmond AS. The hospital anxiety and depression scale. BMJ (Clin Res Ed). 1986;292(6516):344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Snaith RP. The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2003;1:29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sinclair VG, Wallston KA. The development and psychometric evaluation of the Brief Resilient Coping Scale. Assessment. 2004;11(1):94-101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lindsey JK, Jones B. Choosing among generalized linear models applied to medical data. Stat Med. 1998;17(1):59-68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shrout PE, Bolger N. Mediation in experimental and nonexperimental studies: new procedures and recommendations. Psychol Methods. 2002;7(4):422-445. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Magnusson WE. Significance versus magnitude: use of the Johnson-Neyman technique in comparative biology. Physiol Biochem Zool. 2005;78(1):105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Campbell MJ, Machin D, Walters SJ. Medical Statistics: A Textbook for the Health Sciences. 4th ed Oxford, England: John Wiley & Sons; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cohen J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kouris A, Platsidaki E, Christodoulou C, et al. Quality of life and psychosocial implications in patients with hidradenitis suppurativa. Dermatology. 2016;232(6):687-691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tee SI, Lim ZV, Theng CT, Chan KL, Giam YC. A prospective cross-sectional study of anxiety and depression in patients with psoriasis in Singapore. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2016;30(7):1159-1164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Vazquez BG, Alikhan A, Weaver AL, Wetter DA, Davis MD. Incidence of hidradenitis suppurativa and associated factors: a population-based study of Olmsted County, Minnesota. J Invest Dermatol. 2013;133(1):97-103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Crowley JJ, Mekkes JR, Zouboulis CC, et al. Association of hidradenitis suppurativa disease severity with increased risk for systemic comorbidities. Br J Dermatol. 2014;171(6):1561-1565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Shavit E, Dreiher J, Freud T, Halevy S, Vinker S, Cohen AD. Psychiatric comorbidities in 3207 patients with hidradenitis suppurativa. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2015;29(2):371-376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lazarus RS, Folkman S. Transactional theory and research on emotions and coping. Eur J Pers. 1987;1:141-169. doi: 10.1002/per.2410010304 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Leppin AL, Bora PR, Tilburt JC, et al. The efficacy of resiliency training programs: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized trials. PLoS One. 2014;9(10):e111420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Richards SH, Anderson L, Jenkinson CE, et al. Psychological interventions for coronary heart disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017;4:CD002902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Fava GA, Tomba E. Increasing psychological well-being and resilience by psychotherapeutic methods. J Pers. 2009;77(6):1903-1934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Fava GA, Cosci F, Guidi J, Tomba E. Well-being therapy in depression: new insights into the role of psychological well-being in the clinical process. Depress Anxiety. 2017;34(9):801-808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]