Abstract

Importance

People diagnosed with psoriasis have an increased risk of premature mortality, but the underlying reasons for this mortality gap are unclear.

Objective

To investigate whether patients with psoriasis have an elevated risk of alcohol-related mortality.

Design, Setting, and Participants

An incident cohort of patients with psoriasis aged 18 years and older was delineated for 1998 through 2014 using the Clinical Practice Research Datalink (CPRD) and linked to Hospital Episode Statistics (HES) and Office for National Statistics (ONS) mortality records. Patients with psoriasis were matched with up to 20 comparison patients without psoriasis on age, sex, and general practice.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Alcohol-related deaths were ascertained via the Office for National Statistics mortality records. A stratified Cox proportional hazard model was used to estimate the cause-specific hazard ratio for alcohol-related death, with adjustment for socioeconomic status.

Results

The cohort included 55 537 with psoriasis and 854 314 patients without psoriasis. Median (interquartile) age at index date was 47 (27) years; 408 230 of total patients (44.9%) were men. During a median (IQR) of 4.4 (6.2) years of follow-up, the alcohol-related mortality rate was 4.8 per 10 000 person-years (95% CI, 4.1-5.6; n = 152) for the psoriasis cohort, vs 2.5 per 10 000 (95% CI, 2.4- 2.7; n = 1118) for the comparison cohort. The hazard ratio for alcohol-related death in patients with psoriasis was 1.58 (95% CI, 1.31-1.91), and the predominant causes of alcohol-related deaths were alcoholic liver disease (65.1%), fibrosis and cirrhosis of the liver (23.7%), and mental and behavioral disorders due to alcohol (7.9%).

Conclusions and Relevance

People with psoriasis have approximately a 60% greater risk of dying due to alcohol-related causes compared with peers of the same age and sex in the general population. This appears to be a key contributor to the premature mortality gap. These findings call for routine screening, identification and treatment, using the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT-C) in both primary and secondary care to detect alcohol consumption and misuse among people diagnosed with psoriasis.

This cohort study investigates whether patients with psoriasis have an elevated risk of alcohol-related mortality.

Key Points

Question

Do people with psoriasis have an elevated risk of alcohol-related mortality?

Findings

In this population-based cohort study, the adjusted hazard ratio of alcohol-related mortality for patients with psoriasis was 1.58 (95% CI, 1.31-1.91) compared with patients without psoriasis.

Meaning

The elevated risk of alcohol-related mortality found in people with psoriasis calls for routine screening, identification, and treatment using the simple Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT-C) in both primary and secondary health care to detect alcohol consumption and misuse among people diagnosed with psoriasis.

Introduction

Psoriasis is a common, currently incurable, immune-mediated skin disease, with a prevalence of between 0.9% and 8.5% in Western countries. Recently, we have shown that, despite an overall decrease in mortality over the last 15 years, people with psoriasis nonetheless still die prematurely vs individuals without the disease. These findings call for a greater understanding of excess mortality linked with psoriasis. Excessive alcohol consumption is recognized in as many as one-third of patients with moderate to severe psoriasis. Furthermore, there is a correlation between increased alcohol intake and extent of body surface area involvement by psoriasis. Patients with increased alcohol intake may also report significantly higher levels of anxiety, depression, and psychosocial challenges. Consequently, alcohol misuse may be considered as a maladaptive behavior, used by affected individuals to manage their psychological distress.

Earlier studies found that people affected by severe psoriasis had a greater prevalence of, and elevated risk of, dying of liver disease and of gastrointestinal disease. However, only 2 studies from the United States and Finland specifically examined death due to cirrhosis or alcohol-related mortality in people with psoriasis. These studies are at least 2 decades old and they examined patients with severe psoriasis identified from hospital settings.

To our knowledge, no study has specifically investigated the relative risk of dying from alcohol-related causes among people with psoriasis in the general population.

Methods

Data Source and Study Design

This cohort study was carried out using the UK Clinical Practice Research Datalink (CPRD). The CPRD contains complete patient information from 711 participating general practices in the United Kingdom, with diagnoses, test results, prescriptions and hospital referrals recorded. Read coding is used to record diagnoses within CPRD. We examined the 398 CPRD practices in England that were also linked to the national Hospital Episode Statistics (HES) and the Office for National Statistics (ONS) mortality records. Linkage is available at individual-level for those patients registered at practices that have consented to data linkage. Linkage between data sets is undertaken using a deterministic linkage algorithm, based on a patient’s exact National Health Service (NHS) identification number, sex, date of birth, and residential postcode. The study was approved by the Independent Scientific Advisory Committee (ISAC) for Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency database research (ISAC approval 15_033R) and is reported in line with the recommendations of the RECORD statement. This population-based study was conducted using anonymized electronic health records that were extracted by a third party and deidentified before they were made available for research purposes. Hence, patient consent was not required.

The psoriasis cohort comprised adult patients (18 years and older), identified in the CPRD, with their first diagnosis of psoriasis between January 1, 1998, and March 3, 2014. Patients were eligible for linkage to the HES and ONS mortality records and were registered in the practice for at least 1 year prior to being diagnosed with psoriasis. The index date was set as the first diagnosis recorded during the study window. Up to 20 comparison patients, without a diagnosis of psoriasis, were matched by age, sex, and general practice on index date. The reason for matching with this number of unaffected comparison patients was the rarity of alcohol-related death as an outcome, to thereby maximize statistical power and precision and to preclude the occurrence of very small cell values among the comparison cohort. The comparison patients were required to have been in contact with the general practice within 6 months of the index date of the patients with psoriasis to whom they were matched. The selection of patients with and without psoriasis from the same population at risk and identifying them from the same general practice and during the same time-window was implemented to thereby avoid potential selection, information, and detection biases. All patients included in the study were followed-up from the index date to the end of the study observation period (March 31, 2014), or to the last date of data collection from the practice, the date the patient transferred out of the practice or died, whichever came first.

Area-Level Socioeconomic Status

The residential postcodes of patients were linked to the Index of Multiple Deprivation (IMD) 2010. The IMD is an area-level weighted combination of the following seven domains of deprivation: income, employment, health and disability, education skills and training, barriers to housing and services, living environment, and crime. It is calculated at the Lower-layer Super Output Areas (LSOA) level covering approximately 1500 residents. The IMD scores were aggregated into quintiles, where 1 corresponded to the least deprived area and 5 to the most deprived area.

Measurement of Alcohol Consumption

Information on alcohol consumption was extracted using an existing algorithm modified for this study (eFigure 1 in the Supplement). In summary, the most recent record, prior to or recorded on the index date, was used to determine the alcohol consumption level. If no information on alcohol consumption was available, this was set to “missing.” Alcohol consumption level was categorized as follows: nondrinkers, former drinkers, occasional drinkers, moderate drinkers, and heavy drinkers, according to UK guidelines on alcohol consumption that were in place during the study’s observation period.

Alcohol-Related Mortality and Clinical Management

Cause-specific mortality was determined via linkage of patient electronic health records (primary care: CPRD; secondary care: HES) with ONS mortality records. In the United Kingdom, death certificates are completed by an attending registered medical practitioner, and this information is captured nationally by the ONS. Death certificates are divided into 2 parts, containing the underlying cause of death (part 1) and diseases that may have contributed to the death (part 2). We identified alcohol-related deaths via the underlying cause of death code, according to International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision (ICD-9) and International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, Tenth Revision (ICD-10), as recommended by the ONS. The ONS definition of alcohol-related deaths only includes those causes regarded as resulting directly from harmful alcohol consumption (eFigure 2 in the Supplement) and does not include other diseases where alcohol has been shown to make some etiological contribution, such as cancers of the mouth, esophagus, and liver, or suicide.

Among those who died of alcohol-related causes, the proportion of people, who had previously: (1) been classified as heavy drinkers; (2) prescribed treatment for alcohol dependence (acamprosate, disulfiram, nalmefene and naltrexone); (3) coded for being offered psychological support for alcohol dependence in primary care; or (4) had an admission to hospital for chronic causes, directly attributable to alcohol, were calculated. All of the code lists used are available from http://www.clinicalcodes.org.

Statistical Analysis

For the descriptive analysis, continuous variables were summarized using the median and interquartile range (IQR), whereas discrete variables were reported as percentages per exposure group. All-person and sex-specific alcohol-related death rates per 10 000 person-years, with 95% CIs and median age at death (IQR), were calculated for patients with and without psoriasis. Cumulative incidence functions were calculated for alcohol-related deaths, and deaths due to all other causes combined (other causes of death). A stratified Cox proportional hazard model was fitted to estimate the cause-specific hazard ratio (HR) and 95% CI. The model was adjusted for socioeconomic status, measured according to IMD quintile. Additionally, the following 3 models were fitted separately: interactions between psoriasis and age, sex, and IMD quintile. A sensitivity analysis was performed to assess the robustness of the results, by restricting the analysis to patients not prescribed methotrexate as this could be a potential confounder, given the hepatotoxic effects of this drug. All statistical analyses were performed using Stata version 14 (StataCorp).

Results

In all, 55 537 patients with incident psoriasis, and 854 314 patients in the matched comparison cohort, met the eligibility criteria and were included in the analysis (eFigure 3 in the Supplement). Median (IQR) age at index date was 47 (27) years (Table 1). Patient postcode-level IMD was similarly distributed. At baseline, there was a higher prevalence of being recorded as a heavy drinker in the psoriasis cohort (9.3%) vs the comparison cohort (7.0%) (P < .001; Table 1). During a median (IQR) of 4.4 (6.2) years of follow-up, 152 alcohol-related deaths occurred in the psoriasis cohort and 1118 in the matched comparison cohort. As shown in Table 2, the alcohol-related death rate per 10 000 person-years was higher for the psoriasis cohort (4.8; 95% CI, 4.1-5.6) vs the comparison cohort (2.5; 95% CI, 2.4-2.7). Patients with psoriasis died from alcohol-related causes on average 3 years younger vs those without psoriasis who died from these causes: median (IQR) age at death 55 (16) years vs 58 (17) years, respectively (Table 2). Furthermore, women with psoriasis died from alcohol-related causes at approximately 5 years younger than women without psoriasis who died from these causes. Three diagnostic codes were predominant among the alcohol-related deaths in the psoriasis cohort: alcoholic liver disease (99 cases [65.1%]), fibrosis and cirrhosis of the liver excluding biliary cirrhosis (36 cases [23.7%]), and mental and behavioral disorders due to alcohol misuse (12 cases [7.9%]). These 3 causes together accounted for 147 (96.7%) of the 152 deaths among the individuals diagnosed with psoriasis. The equivalent percentage (92.1%; 1030 of 1118) was lower in the comparison cohort, but the same 3 types of alcohol-related death predominated.

Table 1. Comparison of Patient Characteristics at Baseline for the Psoriasis vs Comparison Cohorts.

| Characteristic | No. (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Psoriasis Cohort | Comparison Cohort | |

| No. | 55 537 | 854 314 |

| Men | 26 795 (48.2) | 381 435 (44.6) |

| Women | 28 742 (51.7) | 472 879 (55.3) |

| Age, median (IQR) | 48 (28) | 47 (28) |

| IMD score quintilea | ||

| 1 (least deprived) | 12 887 (23.2) | 206 121 (24.1) |

| 2 | 12 608 (22.7) | 197 246 (23.1) |

| 3 | 11 107 (20.0) | 170 642 (20.0) |

| 4 | 10 598 (19.1) | 156 342 (18.3) |

| 5 (most deprived) | 8277 (14.9) | 122 936 (14.4) |

| Missing | 60 (0.1) | 1027 (0.1) |

| Alcohol consumptionb | ||

| Nondrinker | 5463 (9.8) | 91 739 (10.7) |

| Former drinker | 2582 (4.6) | 36 102 (4.2) |

| Occasional drinkers | 6512 (11.7) | 102 646 (12.0) |

| Moderate drinkers | 22 714 (40.9) | 349 182 (40.9) |

| Heavy drinkers | 5146 (9.3) | 60 054 (7.0) |

| Missing | 13 117 (23.6) | 214 591 (25.1) |

Abbreviations: IMD, Index of Multiple Deprivation; IQR, interquartile range.

The Index of Multiple Deprivation, which measures socioeconomic status at area level, is divided into quintiles: 1 corresponds to the least deprived area; 5, the most deprived area.

The variable includes the most recent record of alcohol consumption prior to or on the index date.

Table 2. Event Counts and Crude Incidence Rates of Alcohol-Related Death in the Psoriasis and Comparison Cohorts.

| Characteristics | Psoriasis Cohort | Comparison Cohort |

|---|---|---|

| Patients per cohort, No. | 55 537 | 854 314 |

| Follow-up, median (IQR), y | 5.0 (6.4) | 4.3 (6.1) |

| Person-years, No. | 318 435 | 4 455 669 |

| No. of alcohol-related deaths, No. (%) | 152 (0.3) | 1118 (0.1) |

| Alcohol-related mortality rate (95% CI)a | 4.8 (4.1-5.6) | 2.5 (2.4-2.7) |

| Female | 3.9 (3.1-5.0) | 1.9 (1.7-2.1) |

| Male | 5.7 (4.6-7.0) | 3.3 (3.0-3.5) |

| Age at death for alcohol-related death, median (IQR), y | 55 (16) | 58 (17) |

| Female | 55 (18) | 60 (18) |

| Male | 56 (14) | 57 (16) |

Abbreviation: IQR, interquartile range.

Crude mortality rates per 10 000 person-years.

The electronic health records revealed that most patients who died of alcohol-related causes in the psoriasis cohort or in the comparison cohort had at least 1 lifetime hospital admission for a chronic alcohol-related condition (85.5% and 79.0%, respectively). Among those patients who died due to alcohol-related disease 82.2% in the psoriasis group and 75.5%in the comparison group had been classified as heavy drinkers in their primary care medical records. However, 17.8% of patients who died of alcohol-related causes in the psoriasis cohort and 24.3% in the comparison cohort, never received a lifetime diagnosis of excessive alcohol consumption, or a prescription in primary care for alcohol dependence. Only a small proportion of these patients received pharmacotherapy for alcohol dependence or was coded as being offered psychological support (Table 3).

Table 3. Proportion of Alcohol-Related Deaths in the Psoriasis and Comparison Cohorts With History of Alcohol Misuse Indicated in Patient Primary (CPRD) or Secondary Care (HES) Records.

| History of Alcohol Misuse Indicators | No. (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Psoriasis Cohort (n = 152) | Comparison Cohort (n = 1118) | |

| Coded as being a heavy drinker | 125 (82.2) | 844 (75.5) |

| Prescription for alcohol dependence | 16 (10.5) | 122 (10.9) |

| Coded as being offered psychological support in primary care | 30 (19.7) | 161 (14.4) |

| Hospital admission for chronic causes entirely attributable to alcohol | 130 (85.5) | 883 (79.0) |

Abbreviations: CPRD, clinical practice research datalink; HES, hospital episode statistics.

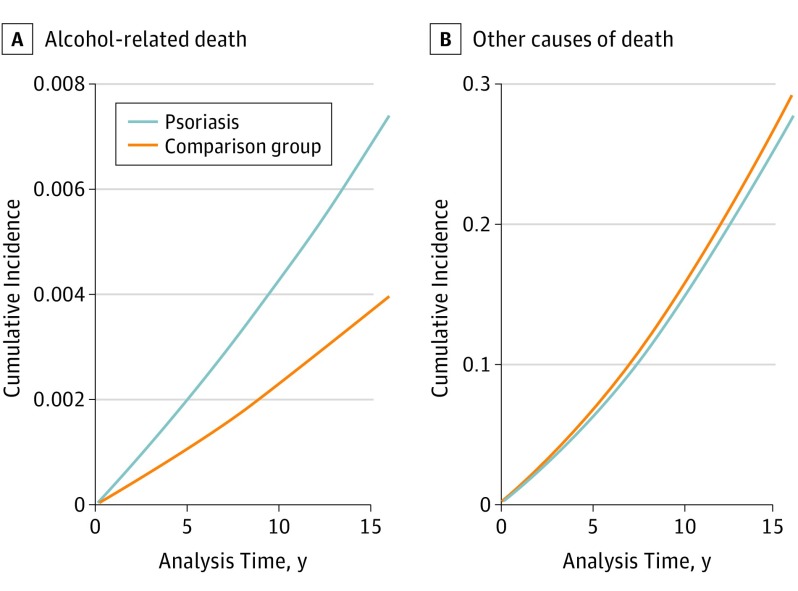

The cause-specific hazard of alcohol-related death was increased by 58% (HR, 1.58; 95% CI, 1.31-1.91) in the psoriasis cohort vs the comparison cohort, and the cause-specific hazard of other causes of death was lower by 19% (HR, 0.81; 95% CI, 0.78-0.83), as reported in Table 4. For patients with psoriasis, the cumulative incidence of alcohol-related death tended to increase much more rapidly than in the comparison group across the follow-up period. The 16-year cumulative incidence of alcohol-related death in the psoriasis and comparison cohorts were 0.007% (95% CI, 0.005-0.009) and 0.005% (95% CI, 0.003-0.005), respectively (Figure). There was no evidence of variability in relative risk by age (P = .45), sex (P = .59), or IMD quintile (P = .28). The sensitivity analysis, excluding people prescribed methotrexate, confirmed that psoriasis was associated with an elevated alcohol-related mortality risk (HR, 1.66; 95% CI, 1.37-2.01).

Table 4. Cause-Specific Hazard Ratios for Alcohol-Related Death and Other Causes of Death.

| Analysis | Alcohol-Related Death, HR (95% CI) | P Value | Other Causes of Death, HR (95% CI) | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unadjusted | 1.60 (1.33-1.93) | <.001 | 0.81 (0.78-0.83) | <.001 |

| Primarya | 1.58 (1.31-1.91) | <.001 | 0.81 (0.78-0.83) | <.001 |

| Excluding people who were prescribed MTXa | 1.66 (1.37-2.01) | <.001 | 0.78 (0.75-0.80) | <.001 |

Abbreviations: HR, hazard ratio; MTX, methotrexate.

Adjusted for Index of Multiple Deprivation quintile.

Figure. Cumulative Incidence Functions for Alcohol-Related Death and Other Causes of Death .

The figure shows the cumulative incidence functions for (A) alcohol-related death and (B) other causes of death in the psoriasis and comparison cohorts across the maximum 16 years of follow-up.

Discussion

Main Findings

People diagnosed with psoriasis had a greater risk of dying, on average 3 years younger, due to alcohol-related causes, compared with the general population. Moreover, although there was no evidence of a variation in relative risk by sex, women with psoriasis died of alcohol-related causes at considerably younger age (approximately 5 years) than women without psoriasis who died from these causes. The cumulative incidence functions also showed that the incidence of alcohol-related mortality increased much more rapidly during follow-up in patients with psoriasis. Similar findings were evident after excluding patients, who were prescribed methotrexate in primary care.

Comparison to Other Studies

Consistent with other studies, we found a raised prevalence of alcohol misuse in the psoriasis cohort. Our results are also consistent with those that found an increased mortality risk due to liver disease in patients with psoriasis. In examining cause-specific mortality, these earlier studies found that people affected by psoriasis had a greater risk of dying from liver disease, with a standard mortality ratio of 4.04 (95% CI 2.76–5.70) if they had the most severe form of the disease, or with a HR of 2.00 (95% CI 1.34-2.99) for mild psoriasis, and 4.26 (95% CI 1.87-9.73) for severe psoriasis. Higher mortality rates from gastrointestinal diseases have also been reported among patients with mild (0.9 per 1000 person-years, 95% CI 0.9-1.0) and severe (1.8 per 1000 person-years, 95% CI 1.6-2.0) psoriasis, compared to 0.4 per 1000 person-years (95% CI 0.4-0.4) in the general population. Similar to findings reported by Stern and Lange (1988) and Poikolainen et al. (1999), we found that the risk of death, due to cirrhosis and other causes, directly attributable to alcohol misuse, is greater in people with psoriasis than it is in those without the condition. The first study, using a cohort of 1380 people with moderate-to-severe psoriasis, exposed to Photochemotherapy (PUVA), and which investigated specific causes of death, found that psoriasis was positively associated with death due to cirrhosis (standard mortality ratio, 4.7; 95% CI, 3.1-6.8).The second study, analyzing more than 5000 patients hospitalized for psoriasis, reported elevated mortality, directly attributable to alcohol (standard mortality ratio 4.46; 95% CI, 3.60-5.45 for men and standard mortality ratio, 5.60; 95% CI, 2.98-8.65 for women).

Strengths and Limitations of the Study

Major strengths of this study included the linkage of primary care electronic health records to national mortality records to ascertain causes of death and also the adoption of a stringent definition to identify alcohol-related mortality. The use of the ONS definition included only those causes of death directly attributable to chronic or acute alcohol misuse. Earlier studies are likely to have misclassified the outcome by using broader definitions, including diagnoses, that are associated with alcohol but not directly attributable to acute or chronic excessive alcohol consumption. In contrast to Stern and Lange and Poikolainen et al, we examined risk within a population-based cohort of people with psoriasis, rather than within those with just the most severe form of the disease or in cases hospitalized for psoriasis. In a sensitivity analysis, we examined whether the observed elevated alcohol-related death risk might be explained by hepatotoxic effects due to methotrexate use rather than excessive alcohol consumption by excluding patients prescribed methotrexate. A further strength of our study was the size and coverage of the data source, which yielded a cohort broadly representative of all patients registered in primary care in England. This provided abundant statistical power to examine this relatively rare cause-specific mortality outcome. Only 1 variable in our cohort study was affected by missing data: specifically, socioeconomic status (IMD score) contained a negligible amount of missing data (0.1%). Nonetheless, some limitations of the study should be acknowledged. These include the fact that information on methotrexate use was identified from prescriptions issued in primary care, as no information on hospital prescribing was available. However, patients receiving low-dose methotrexate for psoriasis are commonly managed through shared-care arrangements between hospital and primary care health care providers. Second, we were unable to examine risk of alcohol-related mortality by severity of psoriasis, as validated measures of disease severity are not routinely recorded in patient electronic health records in primary care.

Interpretation of the Findings

Individuals with psoriasis face psychological distress and psychosocial challenges, often as a consequence of the stigmatizing nature of the disease, and these in turn can lead to chronic alcohol misuse and dependence. Highlighting the dual stigma of psoriasis and problem drinking is important. Alcohol misuse is perceived as a self-inflicted lifestyle choice rather than a disease. Hence, patients are often reticent to acknowledge the problem. People affected by psoriasis have a higher prevalence of excessive alcohol consumption and an elevated risk of dying due to alcohol-related causes compared with the general population of the same age and sex, independent of socioeconomic status. Our findings also highlight that alcohol misuse often remains unidentified and undertreated in primary care.

Only a very small proportion of individuals who died from alcohol-related causes were prescribed pharmacotherapy or coded as being offered psychological support. Nonetheless, the majority of these patients had previously been hospitalized for alcohol-related problems. These findings concur with those from a recent study on prescribing patterns for alcohol dependence in the United Kingdom, which concluded that only 12% of people with alcohol dependence were prescribed treatment in primary care. In recent years, the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidelines in England and systematic reviews of the evidence-base have recommended a combination of pharmacotherapy and psychological counseling, neither of which are regularly deployed for people with alcohol dependence.

Alcohol Treatment Services and Implications for Clinicians

There is also a need to detect and intervene earlier in liver disease and the main determinant of long-term survival for these patients is to abstain from drinking. Screening and brief interventions, in both primary and secondary health care, and hospital alcohol care teams help patients achieve abstinence, improve health harms and prognosis, and remove the stigma of self-inflicted disease. Our study has reinforced the findings from the National Confidential Enquiry into Patient Outcome and Death report, highlighting the long-term nature of missed opportunities, such as delays in referral of patients for specialist alcohol and liver care, and missed opportunities for brief interventions during previous admissions.

Conclusions

Our findings also indicate that health care practitioners, with responsibility for the care of patients with psoriasis, should be more aware of the psychological difficulties that this group of patients face. Routine screening, identification and treatment, using the simple, shortened form (AUDIT-C) of the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test screening tool, developed by the World Health Organization to detect the early signs of hazardous, harmful, and dependent alcohol consumption should be implemented in both primary and secondary care to detect alcohol misuse among all people diagnosed with psoriasis. This is critical in hospital dermatology departments, where the most severe cases of psoriasis, in whom alcohol consumption is highest, are cared for. Moreover, there is also an urgent need for effective alcohol and addiction treatment services to be developed, so as to address both health harms and to overcome the stigma experienced by patients with both psoriasis and alcohol problems.

eAppendix. Assessment of alcohol consumption

eFigure 1. Algorithm used to extract information on alcohol consumption

eFigure 2. National Statistics definition of alcohol-related death3

eFigure 3. Flow-chart of patients included in the study

eReferences.

References

- 1.Parisi R, Symmons DPM, Griffiths CEM, Ashcroft DM; Identification and Management of Psoriasis and Associated ComorbidiTy (IMPACT) project team . Global epidemiology of psoriasis: a systematic review of incidence and prevalence. J Invest Dermatol. 2013;133(2):377-385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Springate DA, Parisi R, Kontopantelis E, Reeves D, Griffiths CEM, Ashcroft DM. Incidence, prevalence and mortality of patients with psoriasis: a U.K. population-based cohort study. Br J Dermatol. 2017;176(3):650-658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.World Health Organization Global report on psoriasis. http://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/204417. Accessed June 16, 2017.

- 4.McAleer MA, Mason DL, Cunningham S, et al. Alcohol misuse in patients with psoriasis: identification and relationship to disease severity and psychological distress. Br J Dermatol. 2011;164(6):1256-1261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kirby B, Richards HL, Mason DL, Fortune DG, Main CJ, Griffiths CEM. Alcohol consumption and psychological distress in patients with psoriasis. Br J Dermatol. 2008;158(1):138-140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Al-Jefri K, Newbury-Birch D, Muirhead CR, et al. High prevalence of alcohol use disorders in patients with inflammatory skin diseases [published online March 27, 2017]. Br J Dermatol. doi: 10.1111/bjd.15497 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Poikolainen K, Reunala T, Karvonen J. Smoking, alcohol and life events related to psoriasis among women. Br J Dermatol. 1994;130(4):473-477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yeung H, Takeshita J, Mehta NN, et al. Psoriasis severity and the prevalence of major medical comorbidity: a population-based study. JAMA Dermatol. 2013;149(10):1173-1179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stern RS, Huibregtse A. Very severe psoriasis is associated with increased noncardiovascular mortality but not with increased cardiovascular risk. J Invest Dermatol. 2011;131(5):1159-1166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Svedbom A, Dalén J, Mamolo C, et al. Increased cause-specific mortality in patients with mild and severe psoriasis: a population-based Swedish register study. Acta Derm Venereol. 2015;95(7):809-815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stern RS, Lange R. Cardiovascular disease, cancer, and cause of death in patients with psoriasis: 10 years prospective experience in a cohort of 1,380 patients. J Invest Dermatol. 1988;91(3):197-201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Poikolainen K, Karvonen J, Pukkala E. Excess mortality related to alcohol and smoking among hospital-treated patients with psoriasis. Arch Dermatol. 1999;135(12):1490-1493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Robinson D, Schulz E, Brown P, Price C. Updating the Read Codes: user-interactive maintenance of a dynamic clinical vocabulary. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 1997;4(6):465-472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Benchimol EI, Smeeth L, Guttmann A, et al. ; RECORD Working Committee . The REporting of studies Conducted using Observational Routinely-collected health Data (RECORD) statement. PLoS Med. 2015;12(10):e1001885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Department for Communities and Local Government English indices of deprivation: guidance. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/english-indices-of-deprivation-2010-guidance. Accessed June 16, 2017.

- 16.Bell S, Daskalopoulou M, Rapsomaniki E, et al. Association between clinically recorded alcohol consumption and initial presentation of 12 cardiovascular diseases: population based cohort study using linked health records. BMJ. 2017;356:j909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Department of Health Sensible drinking: the report of an inter-departmental working group. 1995. http://www.dh.gov.uk/prod_consum_dh/groups/dh_digitalassets/@dh/@en/documents/digitalasset/dh_4084702.pdf. Accessed June 16, 2017.

- 18.Breakwell C, Baker A, Griffiths C, Jackson G, Fegan G, Marshall D. Trends and geographical variations in alcohol-related deaths in the United Kingdom, 1991-2004. Health Stat Q. 2007;(33):6-24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Springate DA, Kontopantelis E, Ashcroft DM, et al. ClinicalCodes: an online clinical codes repository to improve the validity and reproducibility of research using electronic medical records. PLoS One. 2014;9(6):e99825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Salahadeen E, Torp-Pedersen C, Gislason G, Hansen PR, Ahlehoff O. Nationwide population-based study of cause-specific death rates in patients with psoriasis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2015;29(5):1002-1005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Thompson A, Ashcroft DM, Owens L, van Staa TP, Pirmohamed M. Drug therapy for alcohol dependence in primary care in the UK: A Clinical Practice Research Datalink study. PLoS One. 2017;12(3):e0173272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.National Institute for Health and Care Excellence Alcohol-use Disorders: Diagnosis, Assessment and Management of Harmful Drinking and Alcohol Dependence. Clinical guideline [CG115]. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/CG115. Accessed June 16, 2017.

- 23.Jonas DE, Amick HR, Feltner C, et al. Pharmacotherapy for adults with alcohol use disorders in outpatient settings: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA. 2014;311(18):1889-1900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Verrill C, Markham H, Templeton A, Carr NJ, Sheron N. Alcohol-related cirrhosis—early abstinence is a key factor in prognosis, even in the most severe cases. Addiction. 2009;104(5):768-774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Moriarty K, Cassidy P, Dalton D, et al. Alcohol-Related Disease. Meeting the challenge of improved quality of care and better use of resources. A Joint Position Paper on behalf of the British Society of Gastroenterology, Alcohol Health Alliance UK & British Association for Study of the Liver. http://www.bsg.org.uk/images/stories/docs/clinical/publications/bsg_alc_disease_10.pdf. Accessed June 16, 2017.

- 26.British Society of Gastroenterology and Bolton NHS Foundation Trust Alcohol Care Teams: reducing acute hospital admissions and improving quality of care. London: NICE, 2016. http://www.nice.org.uk/savingsandproductivityandlocalpracticeresource?ci=http%3a%2f%2farms.evidence.nhs.uk%2fresources%2fQIPP%2f29420%2fattachment%3fniceorg%3dtrue. Accessed June, 16 2017.

- 27.National Confidential Enquiry into Patient Outcome and Death Measuring the units: a review of patients who died with alcohol-related liver disease. http://www.ncepod.org.uk/2013report1/downloads/Measuring%20the%20Units_full%20report.pdf. Accessed June 16, 2017.

- 28.Saunders JB, Aasland OG, Babor TF, de la Fuente JR, Grant M. Development of the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT): WHO collaborative project on early detection of persons with harmful alcohol consumption—II. Addiction. 1993;88(6):791-804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eAppendix. Assessment of alcohol consumption

eFigure 1. Algorithm used to extract information on alcohol consumption

eFigure 2. National Statistics definition of alcohol-related death3

eFigure 3. Flow-chart of patients included in the study

eReferences.