Key Points

Question

What is the resolution rate of chronic urticaria in children, and are there biomarkers that can predict resolution?

Findings

In a cohort of 139 children younger than 18 years, our data demonstrated low (10%) yearly resolution rate of chronic urticaria. Basopenia and positive results from a basophil activation test (BAT) (CD63 level > 1.8%) were associated with higher resolution rate

Meaning

Biomarkers, including BAT results and basophil counts, may help to prognosticate the natural history of chronic urticaria in children.

Abstract

Importance

Chronic urticaria (CU) affects 0.1% to 0.3% of children. Most cases have no identifiable trigger and are classified as chronic spontaneous urticaria (CSU). At least half of patients with CSU may have an autoimmune etiology that can be determined in vitro using the basophil activation test (BAT). While 30% to 55% of CU cases resolve spontaneously within 5 years in adults, the natural history and predictors of resolution in children are not known.

Objective

To assess the comorbidities, natural history of CU, and its subtypes in children and identify predictors of resolution.

Design, Setting, and Participants

We followed a pediatric cohort with chronic urticaria that presented with hives lasting at least 6 weeks between 2013 and 2015 at a single tertiary care referral center.

Exposures

Data were collected on disease activity, comorbidities, physical triggers, BAT results, complete blood cell count, C-reactive protein levels, thyroid-stimulating hormone levels, and thyroid peroxidase antibodies.

Main Outcomes and Measures

We assessed the rate of resolution (defined as absence of hives for at least 1 year with no treatment) and the association with clinical and laboratory markers.

Results

The cohort comprised 139 children younger than 18 years old. Thirty-one patients (20%) had inducible urticaria, most commonly cold induced. Six children had autoimmune comorbidity, such as thyroiditis and type 1 diabetes. Autoimmune disorders (24 patients [17%]) and CU (17 patients [12%]) were common in family members. Positive BAT results (CD63 levels > 1.8%) were found in 58% of patients. Patients with positive BAT results (CD63 level >1.8%) were twice as likely to resolve after 1 year compared with negative BAT results (hazard ratio [HR], 2.33; 95% CI, 1.08-5.05). In contrast, presence of basophils decreased the likelihood of resolution (HR, 0.40; 95% CI, 0.20-0.99). No correlation with age was found. Chronic urticaria resolved in 43 patients, with a rate of resolution of 10.3% per year. Levels of CD63 higher than 1.8% and absence of basophils were associated with earlier disease resolution.

Conclusions and Relevance

Resolution rate in children with CU is low. The presence of certain biomarkers (positive BAT result and basophil count) may help to predict the likelihood of resolution.

This cohort study examined the resolution rate of chronic urticaria in children and whether there are biomarkers that can predict resolution.

Introduction

Chronic urticaria (CU) is defined by the occurrence of wheals, angioedema, or both lasting more than 6 weeks. Physical urticaria (PU) occurs when the CU is associated with a specific physical stimulus (eg, cold urticaria, solar urticaria, delayed pressure urticaria, localized heat urticaria, dermographic urticaria, or vibration urticaria). The point prevalence of CU is 0.5% to 1.0% of the general population, and it affects 0.1% to 0.3% of children. Although to our knowledge, no studies assessing the prevalence of CU in Canadians had been published so far, assuming a similar 0.3% lifetime prevalence, it is likely that more than 100 000 Canadian children are affected by CU.

In 80% of CU cases, hives occur spontaneously, leading to the diagnosis of chronic spontaneous urticaria (CSU). While the exact pathogenesis of CSU remains to be elucidated, patients can be divided into at least 2 subgroups: those whose disease is truly idiopathic, and those who have an autoimmune CSU (40%-50% of adults and children). The presence of autoantibodies that are capable of inducing mast cell (and basophil) degranulation can be established either in vivo with the use of the autologous serum skin test or in vitro with various methods, including the basophil activation test (BAT) using CD63 activation marker. Furthermore, studies of adult patients with CSU suggested that in an additional 15% to 30% of cases of hives could be explained by an “autoallergic” mast cell activation through thyroid peroxidase IgE antibody binding the high-affinity IgE receptor. In children, only a few prospective studies suggested that autoimmune CSU affects about half of pediatric CU cases in Europe and Turkey, while in Thailand autoimmune CSU affects approximately 40% of children. We recently addressed the use of BAT using CD63 expression for the assessment of CSU severity in Canadian children and found that 58% of our pediatric CSU cohort had a positive BAT result (defined as CD63 values >1.8%) suggesting autoimmune urticaria. Furthermore, we demonstrated that BAT was significantly higher in patients with CSU compared with healthy volunteers and correlated positively with disease severity.

Chronic urticaria in adults is considered a self-limited disease, yet it resolves spontaneously within 5 years in only 30% to 55% of adult patients. However, data on the natural history of CU and its subtypes in children are scarce. Furthermore, no prognostic biomarkers have been identified up to this point.

The aim of this study was to establish a registry of pediatric patients with CU to assess clinical characteristics and the presence of comorbidities associated with CU in children and to determine the natural history of CU and identify factors associated with resolution.

Methods

Patients

The study protocol and consent forms were approved by the institutional review board of the McGill University Health Centre (protocol No.12-225) and were in accordance with the guiding principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. Written informed consent was obtained from children’s parents or legal guardians prior to conducting any study-related investigations. In addition, patients older than 7 years were requested to sign a consent form. Participants ages 0 to 17 years were recruited prospectively from the urticaria and dermatology clinics at the Montreal Children’s Hospital from December 2013 to December 2015. Patients were not compensated for their participation.

Complete medical history was taken and physical examination were performed for each patient at the time of study entry and during each follow-up visit. We defined CU by the occurrence of wheals, angioedema, or both lasting more than 6 weeks. Inducible urticarias were identified by proper investigations (ie, suggestive history for physical triggers and appropriate confirmatory provocation testing, as recommended). Other potential causes of urticaria (ie, food and drug allergy and parasites) were identified by history and/or confirmatory testing (a stool sample for ova and parasite identification was obtained at baseline in case of travel to an endemic area in the year prior to presentation with hives, presence of close contact with pets or suggestive symptoms). Data were collected on personal and family history of comorbid conditions, including atopy (defined as the presence of asthma, eczema, or food allergy diagnosed by a physician) and autoimmune diseases and history of medications use.

As part of the standard of care, all patients had a complete blood cell count (CBC) and C-reactive protein (CRP) level measured at baseline. In addition, serum total immunoglobulin E (IgE) and tryptase levels were obtained at baseline. Additional investigations (eg, antinuclear antibody serologic tests, skin biopsy) were performed only if there were any clinical features suggestive of comorbid autoimmune disease or the diagnosis of CU was not clear. Disease severity was assessed using weekly urticaria activity score (UAS7) (weekly average for the previous 12 weeks) at each clinical follow-up visit as previously described.

Treatment regimen was based on the European Academy of Allergy and Clinical Immunology, Global Allergy and Asthma European Network, European Dermatology Forum, and World Allergy Organization recommendations. All patients were prescribed initially a second-generation, nonsedating antihistamine, such as desloratadine or cetirizine, once daily, according to age recommendation for approximately 2 to 4 weeks, and the dose was increased up to 4-fold of the recommended initial dose after 2 to 4 weeks in presence of persistent symptoms. Those with persistent CU despite maximal dosage of antihistamines after 4 weeks were asked to contact the treating physician to be evaluated and to potentially change or intensify the treatment regimen. Third-line treatment options included omalizumab and ketotifen. Antiparasitic medications were given in case of positive stool culture results only.

Assessment of Basophil Activation and Thyroiditis

Basophil activation test using CD63 marker expression was performed. Values higher than 1.8% of basophil activation were considered elevated, as previously described. In addition, levels of thyroid-stimulating hormone, free thyroxine, and IgG thyroid peroxidase antibodies were assessed.

Assessment of Natural History of the Disease

Disease resolution was defined as absence of hives for at least 1 year without treatment (the date of resolution being the last day of active hives) as described in previous studies. All patients were followed up prospectively and assessed for disease resolution. In case of loss to follow-up, patients were called on an annual basis to verify if the disease was still persistent.

Statistical Considerations

Baseline characteristics were summarized using means (SDs) or proportions as appropriate. Kaplan-Meier curves were used to depict unadjusted time to resolution from disease onset per 100 patient-years. Multivariable Cox regression models were used to determine factors associated with resolution (ie, demographic data, including age and sex; UAS7; angioedema; presence of comorbid autoimmune disorders; atopy; family history of hives; presence of inducible urticaria; and laboratory characteristics, including CRP level, absolute basophil count, and BAT findings. The latter 2 were characterized as dichotomous variables (absence of basophils vs levels that are detectable and CD63 levels >1.8% vs levels that are ≤1.8%, respectively). We assessed the effect of age both as continuous as well as categorical variables (age ranges, 0-4 years old, 4-12 years old, and 12-18 years old). We used SAS statistical software (version 9.3; SAS Institute Inc) and R software (version 2.12.0; R Foundation ) to conduct all statistical analyses.

Results

Demographic Data

A total of 139 consecutive children with CU were recruited (Table 1). Our cohort did not include patients with recurrent angioedema and without wheals. There were no cases of refusal to participate. The sex distribution was equal. Almost 70% of children (95) were white (non-Hispanic, non-Middle Eastern white). The mean (SD) age at disease onset was 6.7 (4.7) years [range, 0–17 years]. The mean duration of CU was 2.0 (1.8) years [range, 0.3-8.7 years]. The most common type of CU was CSU (108 [78.0%]). Twenty-two percent of patients (31) had inducible urticaria; of those, approximately a third (11 patients) had CSU as well. The most common subtype of inducible urticaria was cold-induced urticaria (22 patients [15.8%]) followed by a cholinergic (9 [6.5%]), sun-induced (3 [2.2%]), and delayed pressure (1 [0.7%]) urticarias. A quarter of patients had concomitant angioedema symptoms (28% of patients with CSU). Almost all patients (132 [95%]) required a treatment for their symptoms consisting of second-generation antihistamines alone or in resistant cases, in combination with ketotifen (13%) and/or antileukotriene (1.4%) and/or omalizumab (5%).

Table 1. Demographics, Pertinent Clinical Findings, Treatment, and Comorbidities in 139 Patientsa.

| Variable | Age at Recruitment, y | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| <4 (n = 28) |

4-12 (n = 66) |

>12 (n = 45) |

All (n = 139) |

|

| Male sex | 16 (57.1) | 31 (47.0) | 21 (46.7) | 68 (48.9) |

| Race/ethnicity | ||||

| White | 22 (78.6) | 52 (78.8) | 38 (84.4) | 112 (80.6) |

| Non-Hispanic, non-Middle Eastern | 18 (64.3) | 43 (65.2) | 34 (75.6) | 95 (68.3) |

| Middle Eastern | 3 (10.7) | 6 (9.1) | 3 (6.7) | 12 (8.6) |

| Hispanic | 1 (3.6) | 3 (4.5) | 1 (2.2) | 5 (3.6) |

| Asian | 4 (14.3) | 9 (13.6) | 7 (15.6) | 20 (14.4) |

| Black | 0 | 1 (1.5) | 0 | 1 (0.7) |

| Mixed | 0 | 6 (9.1) | 0 | 6 (4.3) |

| Age at onset, median (IQR), y | 1.5 (1.0-2.0) | 5 (3.5-7.3) | 13 (9.5-14) | 6.0 (2.5-10.0) |

| Disease duration, median (IQR), y | 0.8 (0.7-1.4) | 1.7 (1.4-3.5) | 1.9 (1.0-3.1) | 1.6 (0.9-2.9) |

| Parental marital status (2 parents) | 22 (78.6) | 66 (77.3) | 36 (80.0) | 109 (78.4) |

| Parental education (≥college) | 22 (78.6) | 51 (77.3) | 37 (82.2) | 110 (79.1) |

| Personal history of autoimmunity | 1 (3.6) | 1 (1.5) | 4 (8.8) | 6 (4.2) |

| Thyroiditis | 1 (3.6) | 0 | 2 (4.4) | 3 (2.1) |

| Systemic lupus erythematosus | 0 | 0 | 1 (2.2) | 1 (0.7) |

| Insulin-dependent diabetes | 1 (3.6) | 1 (1.5) | 1 (2.2) | 2 (1.4) |

| Other comorbidities | ||||

| Cystic fibrosis | 0 | 1 (1.5) | 0 | 1 (0.7) |

| IgA nephropathy | 0 | 1 (1.5) | 0 | 1 (0.7) |

| Autistic spectrum disorder | 0 | 1 (1.5) | 0 | 1 (0.7) |

| Epilepsy | 0 | 1 (1.5) | 1 (2.2) | 2 (1.4) |

| Treatment | 27 (96.4) | 65 (98.5) | 43 (96.6) | 135 (97.1) |

| Antihistamines | 27 (96.4) | 62 (93.9) | 43 (96.6) | 132 (95.0) |

| Ketotifen | 4 (14.3) | 11 (16.7) | 3 (6.7) | 18 (12.9) |

| Montelukast | 0 | 1 (1.5) | 1 (2.2) | 2 (1.4) |

| Omalizumab | 0 | 5 (7.6) | 2 (4.4) | 7 (5.0) |

| Type of urticaria | ||||

| CSU | 25 (89.3) | 60 (90.9) | 34 (75.6) | 118 (85.6) |

| CSU + inducible | 3 (10.7) | 4 (6.1) | 4 (8.9) | 11 (7.9) |

| Inducibleb | 6 (21.4) | 10 (15.1) | 15 (33.3) | 31 (22.3) |

| Cold | 4 (14.3) | 9 (13.6) | 9 (20.0) | 22 (15.8) |

| Sun | 2 (7.1) | 0 | 1 (2.2) | 3 (2.2) |

| Cholinergic | 0 | 1 (1.5) | 8 (17.8) | 9 (6.5) |

| Delayed pressure | 0 | 0 | 1 (2.2) | 1 (0.7) |

| Associated angioedema | 5 (17.9) | 18 (27.3) | 10 (22.2) | 33 (23.7) |

| UAS7 at first week after study entry, median (IQR) | 3.0 (0.7-9.3) | 6.0 (0.7-17.5) | 4.6 (0.8-11.7) | 4.2 (0.7-14.0) |

| Family history | ||||

| Chronic urticaria | 2 (7.1) | 7 (10.6) | 8 (18.1) | 17 (12.3) |

| Atopy | 5 (17.9) | 20 (30.3) | 5 (11.4) | 30 (21.7) |

| Thyroid disease | 3 (10.7) | 7 (10.6) | 4 (9.1) | 14 (10.1) |

| Systemic lupus Erythematosus | 0 | 0 | 1 (2.3) | 1 (0.7) |

| Autoimmunity otherc | 0 | 4 (6.1) | 5 (11.4) | 9 (6.5) |

Abbreviations: CSU, chronic spontaneous urticaria; IgA, immunoglobulin A; IQR, interquartile range; UAS7; urticaria activity score.

Data are given as number (percentages) except where noted.

Individual numbers for inducible urticaria forms may not add up given that more than 1 trigger was found in some patients.

Autoimmunity other: autoimmune arthritis, inflammatory bowel disease, and multiple sclerosis. NB. One patient (in the group >12 years) was adopted, and, hence, no family history was available.

Regarding comorbidities, the most common was atopy (39 patients [28.0%]) (mainly asthma or atopic dermatitis). Six patients were diagnosed as having a comorbid autoimmune disease: 2 with type 1 diabetes, 3 with autoimmune hypothyroidism, and 1 child with systemic lupus erythematosus. Five children were known to have other, not related, chronic health conditions (Table 1). Interestingly, in 24 children (17%) with CU there was a familial history of autoimmune disease, with autoimmune thyroiditis being the most common (14 patients [10%]). In 17 children (12%), 1 or more immediate family members had a history of CU.

Investigation Results

Most patients (126) had their blood drawn. In most patients, the results were within normal limits (Table 2). Thyroid peroxidase antibodies were positive in 4 patients. Of those, 3 were diagnosed as having Hashimoto thyroiditis and were treated with thyroid replacement therapy. Thyroid-stimulating hormone levels were normal in all patients. A BAT analysis on this cohort of patients was previously described and showed that 59 (57%) of them had positive findings suggesting autoimmune urticaria. Basophils were undetectable in 73 children (60%). C-reactive protein levels were elevated in 10 patients (8%), while 8 patients (6%) had peripheral blood eosinophilia (none had met the criteria for hypereosinophilic syndrome). In one of those patients, stool parasites were found, but urticaria recurred despite the antiparasitic treatment. Immunoglobulin E levels were high in 49 patients (40%), with a mean (SD) of 552.0 (1522.3) μg/L. (To convert IgE to milligrams per liter, multiply by 0.001.) Serum tryptase was within normal limits in all patients.

Table 2. Results of Laboratory Investigations.

| Investigations at Study Entrya | No. (%) |

|---|---|

| Abnormal thyroid function tests | 0 |

| Positive antithyroid peroxidase antibodies (>9 IU/mL) | 4 (3.5) |

| Positive BAT result (CD63 expression >1.8%) | 59 (57.0) |

| Basophiles absent | 73 (60.3) |

| Positive stool examination for parasites | 1 (0.7) |

| CRP level (>5 mg/L) | 10 (8.2) |

| IgE (>240 μg/L) | 49 (39.8) |

| Eosinophil level (>4%) | 8 (6.1) |

| Tryptase level (>13.5 μg/L) | 0 |

Abbreviations: BAT, basophil activation test ; CRP, C-reactive protein.

SI conversion factors: To convert CRP to nanomoles per liter, multiply by 9.524; to convert IgE to milligrams per liter, multiply by 0.001.

Upper limit for normal values is included in parentheses.

Natural History

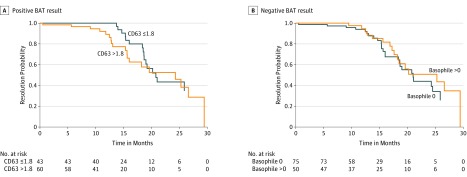

There were 43 cases of resolution over 419 patient-years of follow-up since disease onset giving a resolution rate of 10.3 per 100 patient-years (Figure). Four patients were lost to follow-up, and their disease resolution could not be assessed. Kaplan-Meier curves display time to resolution by higher and lower CD63 levels (Figure, A), and by lower and higher basophil counts (Figure, B). In Cox regression models adjusted for age, sex, and the presence of inducible forms, higher BAT scores, and absence of basophiles were associated with earlier resolution of disease. Patients with positive BAT results (CD63 level >1.8%) were twice as likely to resolve after 1 year compared with negative BAT results (hazard ratio [HR], 2.33; 95% CI, 1.08-5.05). In contrast, presence of basophils decreased the likelihood of resolution (HR, 0.40; 95% CI, 0.20-0.99). No correlation with age was found.

Figure. Survival Analysis of Chronic Urticarial Resolution Rates.

Disease resolution of 10.3 per 100 patient-years. A, Twice, faster resolution in patients with positive basophil activation test (BAT) results was observed in our cohort (P = .02). CD63 level higher than 1.8% represents a positive basophil activation test result, whereas CD63 level of 1.8% or lower is negative. B, Absence of basophils (negative BAT result) was associated with faster resolution of disease (HR, 0.40 [95% CI, 0.20-0,99]; P = .047).

Discussion

We have followed the largest cohort of children to date, to our knowledge, with CU (n = 139) and have shown that the resolution rate is low (10 per 100 patient-years) and that basophil count and CD63 levels can help predict resolution.

In line with findings of previous pediatric studies, CU was as common in girls as in boys, and approximately 20% of our patients had a proven physical and/or inducible trigger (mainly cold). Almost 30% of patients had at least 1 atopic condition, a prevalence grossly similar to the general population. Kolkhir et al have extensively reviewed the topic of potential biomarkers in adult CSU. Based on the published studies available assessing numerous biomarkers, they concluded that CRP and D-dimer levels were significantly and consistently higher in patients with CSU compared with controls and correlated with disease activity but were not specific for CSU. Of those, we have assessed CRP levels and found them to be elevated (>5 mg/L) in only 8.2% of our patients (mean [SD], 2.09 [6.29]) and it did not correlate with either disease resolution or disease severity. However, most of our patients were treated with antihistamines and had a mild disease.

We assessed for possible predictors of resolution, including clinical and laboratory parameters. Surprisingly, high BAT scores and absence of basophils were associated with earlier spontaneous resolution of urticaria. Interestingly, those 2 parameters were previously biologically linked; basopenia was observed mainly in autoimmune subset of CSU and hypothesized to be a result of recruitment of circulating basophils into the skin during disease activity. To our knowledge, there is a paucity of studies assessing this associations in adult CSU and none in pediatric population to our knowledge. Kulthanan et al performed a retrospective medical record review of 337 adult patients with CSU, and autoimmunity was assessed using the autologous serum skin test. In their study, 56.5% of autoimmune CU cases resolved after 1.2 years (only 15 patients) compared with 34.5% of idiopathic forms in 1 year. The reported trend seems in favor of earlier resolution in autoimmune cases; however, the small sample size and different time denominators limit its interpretation. Another study in an adult population with CU reported no association between autoimmune urticaria and probability of resolution. If our findings are confirmed in further studies, it is possible that the favorable prognosis associated with autoimmunity and CD63 level higher than 1.8% is related to the presence of transient viral and bacterial infections that induce autoantibody production. Infections, especially viruses, are common in children and are well accepted pathogenic players in up to 80% of cases of acute urticaria. Furthermore, acute viral infections in children and adults have been proposed to be able to induce transient autoantibodies against self, owing to (1) mimicry between the virus and self or (2) virus-induced cell apoptosis revealing a self neoantigen. Antibodies produced in such cases are usually low titer and transient, but can be high titer, disease specific, and pathogenic. Clinical disease can occur when autoantibodies bind and alter the function on a self-antigen or generate immune complexes that lead to tissue damage. Clinical examples of such interactions include but are not limited to Epstein-Barr virus and systemic lupus erythematosus, hepatitis C virus and cryoglobulinemic vasculitis, mycoplasma, and cold agglutinins. Infection-induced autoimmunity often resolves within months but can also trigger a chronic disease.

Given that the cost of the BAT is approximately Can$2600 for 50 samples and an additional Can$150 for processing and analyzing these samples (over an estimated time of 2 hours), the cost per sample is estimated to be Can$55. Our findings suggest that such a cost may be justified to predict the risk of a more chronic course.

Limitations

Our study has potential limitations. The CU resolution rate was 10.3 per 100 patient-years. Similar rates were reported in adult and pediatric literature. However, our center is a referral center for CU and hence might represent pediatric populations with more severe CU and not be applicable for CU cases seen in primary care practice or the general population. Given that the waiting time to be seen in our clinic ranges from 4 to 8 months, more self-limited cases were likely missed. Hence, it is possible that the 10% annual resolution rate found in our study could underestimate the natural history of CU cases in the general population. In addition, 4 patients were lost to follow-up and in almost a third of cases laboratory data was missing. We did not assess the presence of specific auto antibodies, and hence it is not clear if specific autoantibodies may have an effect on prognosis.

Conclusions

Our results reveal a low rate of resolution of CU in children. Parameters associated with better prognosis included CD63 level higher than 1.8% and, absence of basophils. Studies elucidating the mechanisms accounting for these associations are required to better understand the pathogenesis of CU and to develop appropriate management strategies

References

- 1.Magerl M, Altrichter S, Borzova E, et al. . The definition, diagnostic testing, and management of chronic inducible urticarias: the EAACI/GA(2) LEN/EDF/UNEV Consensus Recommendations 2016 update and revision. Allergy. 2016;71(6):780-802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Trevisonno J, Balram B, Netchiporouk E, Ben-Shoshan M. Physical urticaria: review on classification, triggers and management with special focus on prevalence including a meta-analysis. Postgrad Med. 2015;127(6):565-570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gaig P, Olona M, Muñoz Lejarazu D, et al. . Epidemiology of urticaria in Spain. J Investig Allergol Clin Immunol. 2004;14(3):214-220. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Greaves MW. Chronic urticaria. N Engl J Med. 1995;332(26):1767-1772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sussman G, Hébert J, Gulliver W, et al. . Insights and advances in chronic urticaria: a Canadian perspective. Allergy Asthma Clin Immunol. 2015;11(1):7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Maurer M, Weller K, Bindslev-Jensen C, et al. . Unmet clinical needs in chronic spontaneous urticaria: a GA2LEN task force report. Allergy. 2011;66(3):317-330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lara-Corrales I, Balma-Mena A, Pope E. Chronic urticaria in children. Clin Pediatr (Phila). 2009;48(4):351-355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Data products, 2016. US Census. March 5, 2017. http://www12.statcan.gc.ca/census-recensement/2016/dp-pd/hlt-fst/as/Table.cfm?Lang=E&T=21. Accessed April 2017.

- 9.Fernando S, Broadfoot A. Chronic urticaria: assessment and treatment. Aust Fam Physician. 2010;39(3):135-138. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brunetti L, Francavilla R, Miniello VL, et al. . High prevalence of autoimmune urticaria in children with chronic urticaria. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2004;114(4):922-927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Greaves MW. Chronic idiopathic urticaria. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol. 2003;3(5):363-368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hide M, Francis DM, Grattan CE, Hakimi J, Kochan JP, Greaves MW. Autoantibodies against the high-affinity IgE receptor as a cause of histamine release in chronic urticaria. N Engl J Med. 1993;328(22):1599-1604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Konstantinou GN, Asero R, Maurer M, Sabroe RA, Schmid-Grendelmeier P, Grattan CE. EAACI/GA(2)LEN task force consensus report: the autologous serum skin test in urticaria. Allergy. 2009;64(9):1256-1268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Altrichter S, Peter HJ, Pisarevskaja D, Metz M, Martus P, Maurer M. IgE mediated autoallergy against thyroid peroxidase: a novel pathomechanism of chronic spontaneous urticaria? PLoS One. 2011;6(4):e14794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Du Toit G, Prescott R, Lawrence P, et al. . Autoantibodies to the high-affinity IgE receptor in children with chronic urticaria. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2006;96(2):341-344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Azkur D, Civelek E, Toyran M, et al. . Clinical and etiologic evaluation of the children with chronic urticaria. Allergy Asthma Proc. 2016;37(6):450-457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jirapongsananuruk O, Pongpreuksa S, Sangacharoenkit P, Visitsunthorn N, Vichyanond P. Identification of the etiologies of chronic urticaria in children: a prospective study of 94 patients. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2010;21(3):508-514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Netchiporouk E, Moreau L, Rahme E, Maurer M, Lejtenyi D, Ben-Shoshan M. Positive CD63 basophil activation tests are common in children with chronic spontaneous urticaria and linked to high disease activity. Int Arch Allergy Immunol. 2016;171(2):81-88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kozel MM, Sabroe RA. Chronic urticaria: aetiology, management and current and future treatment options. Drugs. 2004;64(22):2515-2536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.O’Donnell BF, Lawlor F, Simpson J, Morgan M, Greaves MW. The impact of chronic urticaria on the quality of life. Br J Dermatol. 1997;136(2):197-201. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sahiner UM, Civelek E, Tuncer A, et al. . Chronic urticaria: etiology and natural course in children. Int Arch Allergy Immunol. 2011;156(2):224-230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Magerl M, Borzova E, Giménez-Arnau A, et al. ; EAACI/GA2LEN/EDF/UNEV . The definition and diagnostic testing of physical and cholinergic urticarias: EAACI/GA2LEN/EDF/UNEV consensus panel recommendations. Allergy. 2009;64(12):1715-1721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zuberbier T, Aberer W, Asero R, et al. ; Dermatology Section of the European Academy of Allergy and Clinical Immunology; Golbal Allergy and Asthma European Network; European Dermatology Forum; World Allergy Organization . Methods report on the development of the 2013 revision and update of the EAACI/GA2 LEN/EDF/WAO guideline for the definition, classification, diagnosis, and management of urticaria. Allergy. 2014;69(7):e1-e29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Netchiporouk E, Nguyen CH, Thuraisingham T, Jafarian F, Maurer M, Ben-Shoshan M. Management of pediatric chronic spontaneous and physical urticaria patients with omalizumab: case series. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2015;26(6):585-588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Taşkapan O, Harmanyeri Y. Ketotifen and chronic urticaria. Arch Dermatol. 1998;134(2):240-241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Thomsen SF. Epidemiology and natural history of atopic diseases [published online March 24, 2015]. Eur Clin Respir J. doi: 10.3402/ecrj.v2.24642 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kolkhir P, André F, Church MK, Maurer M, Metz M. Potential blood biomarkers in chronic spontaneous urticaria. Clin Exp Allergy. 2017;47(1):19-36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kulthanan K, Jiamton S, Thumpimukvatana N, Pinkaew S. Chronic idiopathic urticaria: prevalence and clinical course. J Dermatol. 2007;34(5):294-301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nuzzo V, Tauchmanova L, Colasanti P, Zuccoli A, Colao A. Idiopathic chronic urticaria and thyroid autoimmunity: Experience of a single center. Dermatoendocrinol. 2011;3(4):255-258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rumbyrt JS, Katz JL, Schocket AL. Resolution of chronic urticaria in patients with thyroid autoimmunity. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1995;96(6, pt 1):901-905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mortureux P, Léauté-Labrèze C, Legrain-Lifermann V, Lamireau T, Sarlangue J, Taïeb A. Acute urticaria in infancy and early childhood: a prospective study. Arch Dermatol. 1998;134(3):319-323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Plumb J, Norlin C, Young PC; Utah Pediatric Practice Based Research Network . Exposures and outcomes of children with urticaria seen in a pediatric practice-based research network: a case-control study. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2001;155(9):1017-1021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sackesen C, Sekerel BE, Orhan F, Kocabas CN, Tuncer A, Adalioglu G. The etiology of different forms of urticaria in childhood. Pediatr Dermatol. 2004;21(2):102-108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Barzilai O, Ram M, Shoenfeld Y. Viral infection can induce the production of autoantibodies. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2007;19(6):636-643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hansen KE, Arnason J, Bridges AJ. Autoantibodies and common viral illnesses. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 1998;27(5):263-271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Khakoo G, Sofianou-Katsoulis A, Perkin MR, Lack G. Clinical features and natural history of physical urticaria in children. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2008;19(4):363-366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Töndury B, Muehleisen B, Ballmer-Weber BK, et al. . The Pictorial Representation of Illness and Self Measure (PRISM) instrument reveals a high burden of suffering in patients with chronic urticaria. J Investig Allergol Clin Immunol. 2011;21(2):93-100. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]