Key Points

Question

Is the high risk of cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) after organ transplantation declining?

Findings

In this population-based cohort study, adjusting for age, follow-up time, and background population risk, we found that the risk of SCC in kidney, heart, lung, and liver transplant recipients in Norway from 1968 through 2012 peaked in patients who underwent transplantation from 1983 through 1987 and declined in those who underwent transplantation in 1993 and later, reaching less than half of what the risk was from 1983 through 1987.

Meaning

Less aggressive and more individualized immunosuppressive treatment may explain the decline in the risk of posttransplant SCC. Close medical and dermatological follow-up of transplant recipients remains essential.

Abstract

Importance

The high risk of skin cancer after organ transplantation is a major clinical challenge and well documented, but reports on temporal trends in the risk of posttransplant cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) are few and appear contradictory.

Objective

To study temporal trends for the risk of skin cancer, particularly SCC, after organ transplantation.

Design, Setting, and Participants

Population-based, nationwide, prospective cohort study of 8026 patients receiving a kidney, heart, lung, or liver transplant in Norway from 1968 through 2012 using patient data linked to a national cancer registry. The study was conducted in a large organ transplantation center that serves the entire Norwegian population of approximately 5.2 million.

Exposures

Receiving a solid organ transplant owing to late-stage organ failure, followed by long-term immunosuppressive treatment according to graft-specific treatment protocols.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Occurrence of first posttransplant SCC, melanoma, or Kaposi sarcoma of the skin. Risk of skin cancer was analyzed using standardized incidence ratios (SIRs) and, for SCC, multivariable Poisson regression analysis of SIR ratios, adjusting for 5-year time period of transplantation, different follow-up time, age, sex, and type of organ.

Results

The study cohort included 8026 organ transplant recipients, 5224 men (65.1%), with a mean age at transplantation of 48.5 years. Median follow-up time was 6.7 years per recipient; total follow-up time, 69 590 person-years. The overall SIRs for SCC, melanoma, and Kaposi sarcoma were 51.9 (95% CI, 48.4-55.5), 2.4 (95% CI, 1.9-3.0), and 54.9 (95% CI, 27.4-98.2), respectively. In those who underwent transplantation in the 1983-1987 period, the unadjusted SIR for SCC was 102.7 (95%, 85.8-122.1), declining to 21.6 (95% CI, 16.8-27.0) in those who underwent transplantation in the 2003-2007 period. Adjusting for different follow-up times and background population risks, as well as age, graft organ, and sex, a decline in the SIR for SCC was found, with SIR peaking in patients who underwent transplantation in the 1983-1987 period and later declining to less than half in patients who underwent transplantation in the 1998-2002, 2003-2007, and 2008-2012 periods, with the relative SIRs being 0.42 (95% CI, 0.32-0.55), 0.31 (95% CI, 0.22-0.42), and 0.44 (95% CI, 0.30-0.66), respectively.

Conclusions and Relevance

The risk of SCC after organ transplantation has declined significantly since the mid-1980s in Norway. Less aggressive and more individualized immunosuppressive treatment and close clinical follow-up may explain the decline. Still, the risk of SCC in organ transplant recipients remains much higher than in the general population and should be of continuous concern for dermatologists, transplant physicians, and patients.

This population-based nationwide cohort study evaluates the long-term change in the risk of skin cancer after organ transplantation in Norway.

Introduction

The high risk of skin cancer after solid organ transplantation is a major clinical challenge and is well documented, but it is unclear whether the risk has changed during the last decades. In a large and comprehensive study on cancer after organ transplantation in Sweden, the authors report no significant differences in the risk of posttransplant cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) between patients who underwent transplantation in the 1980s, 1990s, and 2000s. This is in contrast to a smaller Dutch study, primarily analyzing posttransplant SCC as a risk factor for developing noncutaneous cancer and in contrast to the clinical experience of dermatologists at several transplantation centers, all reporting a decline in the incidence of SCC among transplant recipients (TRs) who underwent kidney transplantation in recent decades (Jan Nico Bouwes Bavinck, MD, PhD, Leiden University Medical Center, personal communication, February 3, 2017).

To challenge the notion of a stable increased risk of SCC after organ transplantation, we set out to study the risk of SCC, cutaneous melanoma, and cutaneous Kaposi sarcoma in the complete cohort of kidney, heart, lung, and liver TRs in Norway in the 1968-2012 period, with a special emphasis on temporal trends, taking advantage of a high-quality national cancer registry to identify organ TRs (OTRs) with skin cancer.

Methods

All organ transplantations in Norway (population in 2016, 5.2 million) are performed at Oslo University Hospital (formerly known as Rikshospitalet). All patients who received their first kidney (from 1968), heart (from 1983), lung (from 1986), or liver (from 1984) up to December 31, 2012 (n = 8278) were included. Patients with both kidney and pancreas transplants were categorized as kidney TRs, and patients with both lung and heart transplants as lung TRs. We excluded patients who died or emigrated within the first 30 days after transplantation (n = 211) and patients with previous skin cancer or registered skin cancer within 30 days after transplantation (n = 41), yielding a study cohort of 8026 OTRs.

Maintenance immunosuppressive therapy was given according to organ-specific treatment protocols that were revised at certain time points during the study period, in line with international guidelines and practice in most countries, including Sweden:

All kidney TRs who underwent transplantation before 1983 were treated with dual immunosuppression with azathioprine and prednisolone.

From January 1983, de novo OTRs were treated with cyclosporin-based immunosuppression, most of them with triple immunosuppression, ie, cyclosporin, azathioprine, and prednisolone. Heart TRs and especially lung TRs were generally given higher doses of cyclosporin than kidney TRs. In the 1990s, cyclosporin oral emulsion and treatment monitoring based on blood cyclosporin concentrations were introduced.

In the 1990s, azathioprine was increasingly replaced by mycophenolate mofetil in most OTRs and cyclosporin with tacrolimus in some OTRs. Most liver TRs were treated with tacrolimus and with lower doses than in kidney and heart TRs.

Sirolimus and everolimus, both mTOR (mechanistic target of rapamycin) inhibitors, were included in some treatment protocols in the early 2000s, with cyclosporin being either discontinued or reduced in dose, but used only in a limited number of patients.

Data on individual treatment, including induction and rejection therapy and the use of photosensitizing drugs, were not available.

Data on OTRs were retrieved from the hospital’s transplantation registries. Those OTRs diagnosed with at least 1 SCC, melanoma, or Kaposi sarcoma after their transplantation were identified by linkage to the Cancer Registry of Norway. Since 1952, this registry has received compulsory information on all cancer patients in the Norwegian population, based on clinical records, pathology reports, and death certificates. Completeness and quality of this registry have been found to be very good. Each cancer type was analyzed separately. Patients were followed from date of first transplantation and censored at the date of first cancer diagnosis, death, emigration, or end of study, ie, December 31, 2013, whichever occurred first. Basal cell carcinoma was not included, as registration of this cancer type is not compulsory in Norway.

The study was approved by the Regional Committee for Ethics in Medical and Healthcare Research (Reference: 2012/1154/REK) and performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, including participant written informed consent.

Statistical Analysis

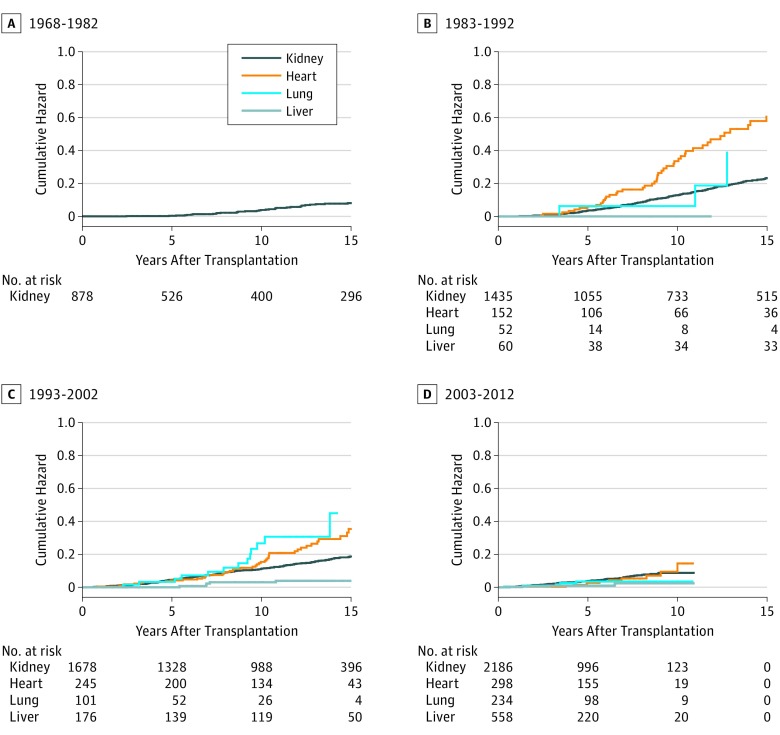

Cumulative hazards of SCC, calculated for various subgroups according to type of graft organ and time period of transplantation (1968-1982, 1983-1992, 1993-2002, and 2003-2012), are presented for descriptive purposes. Hazard ratios with 95% confidence intervals (CI) were estimated to compare the risk of SCC over 5-year time periods of transplantation, adjusting for type of graft organ, sex, and age at transplantation (<30, 30-39, 40-49, 50-59, and ≥60 years), using a Cox proportional hazard regression model with time since transplantation as time scale. This model implicitly adjusts for follow-up time.

To estimate the relative risk of skin cancer in OTRs compared with the general population, the standardized incidence ratio (SIR) was calculated as the ratio between the observed number of cases in OTRs and the expected numbers based on the incidence in the general population stratified by age, sex, and calendar year. Exact Poisson 95% CIs for SIRs were calculated. The SIRs for SCC were calculated for subgroups according to type of graft organ, sex, age at transplantation, 5-year time period of transplantation, and follow-up time after transplantation.

To depict temporal trends in relative risk of SCC in OTRs vs the general population, we estimated unadjusted SIR ratios and adjusted SIR ratios, using Poisson regression with expected number of cases as offset. The covariates were defined as in the Cox regression model with addition of a variable for follow-up time since transplantation categorized into 5-year periods, with a last category for 20 years or longer of follow-up. For both models, a test for linear trend was performed, restricted to the reference time period 1983 through 1987 or later, treating time period as a continuous variable and testing the null hypothesis that the regression coefficient was equal to 0.

The statistical software package Stata 14 (StataCorp LLC) was used for all analyses.

Results

The cohort included 8026 OTRs with a total follow-up time of 69 590 person-years. Demographic and clinical characteristics are detailed in Table 1.

Table 1. Demographic and Clinical Data on 8026 Organ Transplant Recipients Who Underwent Transplantation in Norway in the 1968-2012 Period.

| Graft | Patients, No. | Male, % | Mean Age at Transplantation, y | Follow-up, Median, y | Person-years |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 8026 | 5224 (65.1) | 48.5 | 6.7 | 69 590 |

| Kidneya | 6177 | 4052 (65.6) | 49.0 | 7.2 | 57 000 |

| Heart | 695 | 546 (78.6) | 48.8 | 7.2 | 5555 |

| Lungb | 360 | 182 (50.8) | 50.8 | 4.1 | 1819 |

| Liver | 794 | 439 (55.3) | 43.6 | 5.0 | 5216 |

Includes patients with both kidney and pancreas transplants (n = 265) and patients with both kidney and liver transplants (n = 22).

Includes patients with both lung and heart transplants (n = 22).

Following organ transplantation, 831 OTRs developed at least 1 SCC. Cumulative hazards for SCC up to 15 years after transplantation in patients who underwent transplantation in 4 different time periods are shown in the Figure. After the 1968-1982 period, the cumulative hazards for SCC increased sharply in patients who underwent transplantation in the 1983-1992 period, reaching 23% in kidney TRs and 61% in heart TRs. Despite a higher mean age at transplantation, cumulative hazards declined in patients who underwent transplantation in the 1993-2002 period, reaching 19% in kidney TRs and 35% in heart TRs. In patients who underwent transplantation in 2003 or later, cumulative hazards were even lower. A similar decline in cumulative hazards was seen in both lung TRs and liver TRs.

Figure. Cumulative Hazards for Posttransplant Cutaneous SCC in Kidney, Heart, Lung, and Liver Transplant Recipients in Norway by Time Period of Transplantation.

A total of 8026 patients were evaluated; SCC indicates squamous cell carcinoma.

To adjust for confounding factors, a multivariable Cox regression analysis was performed, showing both graft organ, sex, age at transplantation, and 5-year time period of transplantation to be independent risk factors for SCC (Table 2). Compared with those who underwent transplantation in the 1983-1987 period, the risk declined in patients who underwent transplantation in the next 2 decades (all supporting data reported in Table 2; P for trend <.001).

Table 2. Hazard Ratios for Cutaneous Squamous Cell Carcinoma in 8026 Patients Who Underwent Organ Transplantation from 1968 through 2012.

| Variable | Hazard Ratio (95% CI)a |

|---|---|

| Graft organ | |

| Kidney | 1 [Reference] |

| Heart | 1.59 (1.29-1.96) |

| Lung | 1.53 (0.99-2.36) |

| Liver | 0.37 (0.21-0.64) |

| Sex | |

| Female | 1 [Reference] |

| Male | 1.58 (1.35-1.85) |

| Age at transplantation, y | |

| 0-29 | 1 [Reference] |

| 30-39 | 2.79 (2.03-3.84) |

| 40-49 | 4.98 (3.68-6.74) |

| 50-59 | 8.78 (6.49-11.87) |

| ≥60 | 23.87 (17.58-32.40) |

| Time period of transplantation | |

| 1968-1972 | 0.99 (0.61-1.61) |

| 1973-1977 | 0.79 (0.55-1.13) |

| 1978-1982 | 0.65 (0.46-0.91) |

| 1983-1987 | 1 [Reference] |

| 1988-1992 | 1.15 (0.92-1.45) |

| 1993-1997 | 0.83 (0.65-1.06) |

| 1998-2002 | 0.59 (0.45-0.77) |

| 2003-2007 | 0.47 (0.34-0.64) |

| 2008-2012 | 0.83 (0.56-1.24) |

Hazard ratios were estimated using a multivariable Cox proportional hazard regression model.

The overall SIR for SCC in all OTRs was 51.9 (95% CI, 48.4-55.5). The unadjusted SIR for SCC declined in the pre-1983 period, increased from 1983 and then declined after the 1988-1993 period (Table 3). Also, the unadjusted SIR varied with age at transplantation, sex, and type of transplanted organ (Table 3). Adjusting for these factors, follow-up time, and an increasing incidence of SCC in the background population, we conducted a multivariable Poisson regression analysis of SIR ratios that showed a statistically significant decline in the risk of posttransplant SCC over time, with the SIR peaking in those who underwent transplantation in the 1983-1987 period or later, declining to less than half in patients who underwent transplantation in the 1998-2002, 2003-2007, and 2008-2012 periods, with relative SIRs being 0.42 (95% CI, 0.32-0.55), 0.31 (95% CI, 0.22-0.42), and 0.44 (95% CI, 0.30-0.66), respectively (P for trend <.001) (Table 3).

Table 3. Risk of Cutaneous Squamous Cell Carcinoma in 8026 Organ Transplant Recipients in Norway From 1968 Through 2012a.

| Variable | Patients, No. | Person-years | No. of SCCs | Unadjusted | Adjusted SIR Ratio (95% CI) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Observed | Expected | SIR (95% CI) | SIR Ratio | ||||

| Graft organ | |||||||

| Kidney | 6177 | 57 000 | 686 | 13.7 | 50.1 (46.4-54.0) | 1 | 1 [Reference] |

| Heart | 695 | 5555 | 110 | 1.3 | 85.2 (70.0-102.7) | 1.51 | 1.78 (1.44-2.20) |

| Lung | 360 | 1819 | 22 | 0.3 | 69.0 (43.3-104.5) | 0.93 | 1.85 (1.20-2.86) |

| Liver | 794 | 5216 | 13 | 0.7 | 18.1 (9.7-31.0) | 0.21 | 0.42 (0.24-0.74) |

| Sex | |||||||

| Female | 2805 | 25 751 | 221 | 4.2 | 52.6 (45.9-60.0) | 1 | 1 [Reference] |

| Male | 5221 | 43 839 | 610 | 11.8 | 51.6 (47.6-55.9) | 0.98 | 1.13 (0.97-1.33) |

| Age at transplantation, y | |||||||

| 0-29 | 1195 | 17 523 | 69 | 0.2 | 318.3 (247.7-402.9) | 1 | 1 [Reference] |

| 30-39 | 1102 | 12 312 | 95 | 0.5 | 191.2 (154.7-233.8) | 0.60 | 0.55 (0.40-0.77) |

| 40-49 | 1504 | 14 118 | 157 | 1.5 | 106.0 (90.1-124.0) | 0.33 | 0.29 (0.21-0.39) |

| 50-59 | 2019 | 14 435 | 216 | 3.9 | 55.1 (48.0-63.0) | 0.17 | 0.15 (0.11-0.20) |

| ≥60 | 2206 | 11 202 | 294 | 9.9 | 29.7 (26.4-33.3) | 0.09 | 0.11 (0.08-0.15) |

| Transplantation period | |||||||

| 1968-1972 | 115 | 1553 | 21 | 0.1 | 171.7 (106.3-262.4) | 1.67 | 0.98 (0.61-1.59) |

| 1973-1977 | 359 | 4039 | 45 | 0.4 | 126.4 (92.2-169.1) | 1.23 | 0.87 (0.61-1.23) |

| 1978-1982 | 404 | 5010 | 48 | 0.6 | 81.0 (59.7-107.4) | 0.79 | 0.73 (0.52-1.02) |

| 1983-1987 | 734 | 8872 | 129 | 1.3 | 102.7 (85.8-122.1) | 1 | 1 [Reference] |

| 1988-1992 | 938 | 11 272 | 199 | 2.2 | 90.7 (78.6-104.3) | 0.88 | 0.96 (0.76-1.20) |

| 1993-1997 | 1007 | 11 248 | 158 | 2.8 | 57.1 (48.6-66.8) | 0.56 | 0.65 (0.51-0.82) |

| 1998-2002 | 1193 | 11 572 | 120 | 3.6 | 33.5 (27.8-40.1) | 0.33 | 0.42 (0.32-0.55) |

| 2003-2007 | 1463 | 10 423 | 73 | 3.4 | 21.5 (16.8-27.0) | 0.21 | 0.31 (0.22-0.42) |

| 2008-2012 | 1813 | 5601 | 38 | 1.8 | 21.6 (15.3-29.7) | 0.21 | 0.44 (0.30-0.66) |

| Follow-up time, y | |||||||

| 0-4 | 8026 | 31 579 | 193 | 7.1 | 27.3 (23.6-31.4) | 1 | 1 [Reference] |

| 5-9 | 4969 | 18 801 | 268 | 4.7 | 56.4 (49.9-63.6) | 2.1 | 1.67 (1.37-2.03) |

| 10-14 | 2713 | 9883 | 170 | 2.3 | 74.9 (64.1-87.1) | 2.7 | 1.47 (1.17-1.86) |

| 15-19 | 1391 | 5121 | 96 | 1.0 | 92.3 (74.8-112.7) | 3.4 | 1.11 (0.84-1.47) |

| ≥20 | 715 | 4206 | 104 | 0.9 | 116.1 (94.9-140.7) | 4.3 | 0.77 (0.56-1.05) |

Abbreviations: SCC, squamous cell carcinoma; SIR, standardized incidence ratio.

More than 95% of the patients were white; study analyses accounted for the background population risk (unadjusted SIR, unadjusted SIR ratio, and adjusted SIR ratio) using a multivariable Poisson regression, with expected number of cases of SCC as offset.

The overall SIR for melanoma, diagnosed in 72 OTRs, was 2.4 (95% CI, 1.9-3.0) with no significant difference in the risk for type of graft organ, sex, or age at transplantation. The overall SIR for Kaposi sarcoma, diagnosed in 11 OTRs, was 54.9 (95% CI, 27.4-98.2). In contrast to SCC and melanoma, almost all cases of Kaposi sarcoma, ie, 9 of 11 cases, occurred in the first 5 years after transplantation. The numbers of OTRs with melanoma and Kaposi sarcoma were too low to evaluate trends over time.

Discussion

Our main finding, a declining risk of SCC after organ transplantation during the last 2 decades, contradicts the estimates and interpretations in an earlier Swedish study. In our study, the increase in the risk of SCC in kidney TRs from 1983 is likely caused by the inclusion of cyclosporin in the immunosuppression therapy protocol in early 1983, as reported previously by our group. In the Swedish study, OTRs were stratified according to decade of transplantation (ie, 1970s, 1980s, 1990s, and 2000s). Consequently, the subcohort of patients who underwent transplantation in the 1980-1989 period included OTRs both with and without cyclosporin-based therapy regimens. This may have masked a difference in the risk of SCC between these 2 groups (ie, relatively low in those who underwent transplantation before 1983 and very high in those who underwent transplantation from 1983 through 1989) as well as masked a subsequent decline in the risk of SCC in those who underwent transplantation in the following time periods. In a United Kingdom study, no significant difference in the risk of SCCs between OTRs who underwent transplantation before 1985 and those who underwent transplantation in the 1985-2000 period was found, but possible temporal changes within the 1985-2000 period were not reported on. Our finding is consistent with the smaller Dutch study in 1800 kidney TRs, reporting as a secondary finding a decline in the risk of SCC from the late 1980s. In a cohort study with 4246 liver TRs in the Nordic countries, recently presented as a congress abstract, the SIR for “non-melanoma skin cancer,” presumably mostly SCC, declined significantly in the 1990s and 2000s. A recent US cohort study on posttransplant skin cancer included patients who underwent transplantation in 2003 and 2008 only and did not include data on background population risk.

The decline in the risk of posttransplant SCC in the last decades may be caused by several factors; the pathogenesis of posttransplant SCC is complex. The high increase in risk from 1983, the year cyclosporin was introduced, points toward immunosuppressive therapy as a dominant factor. Consequently, much of the decline is probably caused by less aggressive and more individualized immunosuppression therapy. This includes replacing azathioprine with mycophenolate mofetil; azathioprine and UV-A radiation have been shown to generate mutagenic oxidative DNA damage. Also, DNA damage in kidney TRs has been reported to be reversed by replacing azathioprine with mycophenolate mofetil. The carcinogenic effects of azathioprine and cyclosporin are dose dependent, and the introduction of cyclosporin oral emulsion and treatment monitoring based on blood cyclosporin concentrations in the 1990s may have contributed to the use of lower doses for individual patients. Cyclosporin has increasingly been replaced by tacrolimus and other immunosuppressive drugs, and although both tacrolimus and cyclosporin are calcineurin inhibitors with similar modes of action, their adverse-effect profiles are somewhat different. It is, however, unclear whether tacrolimus is less carcinogenic than cyclosporin, as one recent study suggests. Sirolimus and everolimus, both mTOR inhibitors, have been shown to reduce the short-term risk of SCC in kidney TRs with a previous SCC, but these drugs could not have played a major role in the decline of the risk of SCC in our cohort because these drugs were introduced in the treatment protocols as late the early 2000s and were used in only a limited number of patients.

An additional explanation for the decline in the risk of posttransplant SCC may be improved dermatologic follow-up. More eradication of premalignant skin lesions by dermatologists may have prevented such lesions from developing into SCC in more patients, although we have no data on the frequency of dermatological follow-up, and no national guidelines for skin cancer screening in OTRs have been published. An increased awareness among OTRs on the risk of skin cancer and the need for better sun protection may also be important, a notion that is supported by several studies. With improved patient survival after organ transplantation, the declining risk of SCC cannot be explained by competing risk of death.

Epidemiological studies on posttransplant skin cancer, including the present study, are often based on data on first SCC in individual patients because this is the most accurate and consistent measurement for SCC incidence. The overall SIR for SCC in OTRs in our study is comparable with SIRs found in other Northern European studies (Table 4). When additional primary SCCs are included in the analyses, as done in some studies, SIRs are generally found to be higher, reflecting a high incidence of multiple SCCs in OTRs. Interestingly, the highest SIR ever reported for posttransplant SCC was found in kidney TRs followed up to 1989, while lower SIRs are found in a study from the precyclosporin era and in more recent studies (Table 4).

Table 4. Standardized Incidence Ratios for Cutaneous SCC in Cohort Studies of Organ Transplant Recipient.

| Source | Transplantation Period | Country | Organ | Standardized Incidence Ratio | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| First SCC | All SCCs | ||||

| Birkeland et al, 1995 | 1964-1982 | Nordic countriesa | Kidney | 29.0/18.0b,c | NR |

| Hartevelt et al, 1990 | 1966-1988 | The Netherlands | Kidney | NR | 253d |

| Jensen et al, 1999 | 1963-1992 | Norway | Kidney, heart | 65 | NR |

| Lindelöf et al, 2000 | 1970-1994 | Sweden | Solid organ | NR | 108.6/92.8c |

| Adami et al, 2003 | 1970-1997 | Sweden | Solid organ | 56 | NR |

| Moloney et al, 2006 | 1986-2001 | Ireland | Kidney | NR | 33.3b,e |

| Aberg et al, 2008 | 1982-2005 | Finland | Liver | NR | 38.5b |

| Jensen et al, 2010 | 1977-2006 | Denmark | Solid organ | NR | 82 |

| Wisgerhof et al, 2011 | 1996-2006 | The Netherlands | Kidney | 39.6 | NR |

| Harwood et al, 2013 | Up to 2006 | United Kingdom | Solid organ | NR | 153f |

| Krynitz et al, 2013 | 1970-2008 | Sweden | Kidney | NR | 121 |

| Heart, lung | 244 | ||||

| Liver | 32 | ||||

| Hortlund et al, 2017 | 1963-2011 | Sweden | Solid organ | 44.7 | NR |

| 1977-2011 | Denmark | 41.5 | |||

Abbreviations: NR, not reported; SCC, squamous cell carcinoma; SIR, standardized incidence ratio.

Denmark, Finland, Norway, and Sweden.

Nonmelanoma skin cancer.

Males/females.

With background population data from another region.

Followed up from 1994 through 2001.

Not calendar period-based.

We found significant differences in the risk for SCC between OTRs with different types of transplanted organs (Table 3). These findings are consistent with other studies and may be explained by differences in type and dose of immunosuppressive drugs. Patients receiving a kidney and pancreas transplant simultaneously have a higher risk for SCC than kidney TRs, but categorizing these groups separately did not change our estimates significantly (data not shown). The high SIR for SCC in young patients reflects a very low incidence of SCC in young persons in the general population, similar to the low SIR for SCC in older OTRs reflecting a high incidence of SCC in older persons.

We found a statistically significant increased risk of cutaneous melanoma after organ transplantation, confirming our study in kidney and heart TRs from 1999. Later studies found a similar 2- to 3-fold increased risk of melanoma in OTRs. The risk of melanoma in OTRs is considerably lower than the risk of SCC. In contrast to SCC and melanoma, Kaposi sarcoma was mostly observed within the first 5 years after transplantation, yielding a high SIR. These differences reflect different risk factors, etiologic mechanisms, and carcinogenic pathways for the 3 tumor types. In Kaposi sarcoma, human herpesvirus 8 has been shown to play a causative role. Cumulative sun exposure causing DNA damage is considered to be the most important factor for the development of SCC, with a possible involvement of human papillomavirus still unclear. In melanoma, carcinogenesis is linked to high, intermittent sun exposure and mechanisms less affected by immunosuppression and without virus being involved.

A major strength of our study is the use of a national cancer registry with a virtually complete cancer registration. We believe that our cohort stratification, using 5-year time periods of transplantation, is more appropriate than the stratifications used in the Swedish and United Kingdom studies. By separating patients who underwent transplantation before and including 1982 from those who underwent transplantation after the introduction of cyclosporin in January 1983, we were able to document a decline in the risk of SCC in kidney TRs who underwent transplantation in the pre-cyclosporin era, followed by a sharp increase from 1983. Patients who underwent transplantation in the later time periods had shorter follow-up time, but plots of the cumulative hazard by time after transplantation clearly indicate a decline in the risk of SCC up to 15 years after transplantation. This decline is further supported by a multivariable modeling adjusting for different follow-up time, age, and background population risk, as well as graft organ and sex.

Limitations

Our study does not reflect the total cumulative burden of skin cancer in OTRs. A substantial number of OTRs will develop multiple SCCs, as well as basal cell carcinomas, Merkel cell carcinomas, and other forms of skin cancer. Another limitation is not having data on individual immunosuppressive therapy, including induction and rejection therapy. In contrast to most other countries, however, all organ transplantations in Norway are performed at a single transplantation center, contributing to consistent immunosuppressive regimens. All OTRs were given medication according to organ-specific protocols that were revised by the hospital’s transplant physicians at certain time points. Also, the increased risk of skin cancer after organ transplantation has been found to be unrelated to the number of treatments for graft rejection. We did not reevaluate any cancer diagnoses, thus avoiding a possible bias in systematically applying different diagnostic criteria for skin cancer in the study cohort than might have been applied in the background population: histopathologic criteria for some skin tumors may vary between pathologists and studies, particularly regarding keratoacanthoma-like lesions. Data on specific ethnicity, skin type, and sun exposure habits were not available, but the vast majority of the OTRs (ie, >95%) were white. We did not exclude children, but all analyses were adjusted for age at transplantation. We did not exclude patients with retransplants because most of these patients at our center received continuous immunosuppressive therapy.

Conclusions

The decline in the risk of SCC after organ transplantation in recent decades has implications for our understanding of the relationship between SCC and immunosuppressive drugs and highlights the importance of less carcinogenic treatment. The risk of SCC in OTRs continues to be much higher than in the general population, and close medical and dermatological follow-up is therefore essential to reduce the high burden of skin cancer in this increasingly larger patient population.

References

- 1.Euvrard S, Kanitakis J, Claudy A. Skin cancers after organ transplantation. N Engl J Med. 2003;348(17):1681-1691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hofbauer GF, Bouwes Bavinck JN, Euvrard S. Organ transplantation and skin cancer: basic problems and new perspectives. Exp Dermatol. 2010;19(6):473-482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Proby CM, Wisgerhof HC, Casabonne D, Green AC, Harwood CA, Bouwes Bavinck JN. The epidemiology of transplant-associated keratinocyte cancers in different geographical regions. Cancer Treat Res. 2009;146:75-95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Krynitz B, Edgren G, Lindelöf B, et al. . Risk of skin cancer and other malignancies in kidney, liver, heart and lung transplant recipients 1970 to 2008—a Swedish population-based study. Int J Cancer. 2013;132(6):1429-1438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wisgerhof HC, Wolterbeek R, de Fijter JW, Willemze R, Bouwes Bavinck JN. Kidney transplant recipients with cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma have an increased risk of internal malignancy. J Invest Dermatol. 2012;132(9):2176-2183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Larsen IK, Småstuen M, Johannesen TB, et al. . Data quality at the Cancer Registry of Norway: an overview of comparability, completeness, validity and timeliness. Eur J Cancer. 2009;45(7):1218-1231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Frome EL, Checkoway H. Epidemiologic programs for computers and calculators: use of Poisson regression models in estimating incidence rates and ratios. Am J Epidemiol. 1985;121(2):309-323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mäkelä KT, Visuri T, Pulkkinen P, et al. . Cancer incidence and cause-specific mortality in patients with metal-on-metal hip replacements in Finland. Acta Orthop. 2014;85(1):32-38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Robsahm TE, Helsing P, Veierød MB. Cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma in Norway 1963-2011: increasing incidence and stable mortality. Cancer Med. 2015;4(3):472-480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jensen P, Hansen S, Møller B, et al. . Skin cancer in kidney and heart transplant recipients and different long-term immunosuppressive therapy regimens. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999;40(2 Pt 1):177-186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Harwood CA, Mesher D, McGregor JM, et al. . A surveillance model for skin cancer in organ transplant recipients: a 22-year prospective study in an ethnically diverse population. Am J Transplant. 2013;13(1):119-129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Åberg F, Nordin A, Pukkala E, et al. . LBP509—decreasing incidence of cancer after liver transplantation—a Nordic population-based study. J Hepatol. 2016;64:S216-S217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Garrett GL, Blanc PD, Boscardin J, et al. . Incidence of and risk factors for skin cancer in organ transplant recipients in the United States. JAMA Dermatol. 2017;153(3):296-303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.O’Donovan P, Perrett CM, Zhang X, et al. . Azathioprine and UVA light generate mutagenic oxidative DNA damage. Science. 2005;309(5742):1871-1874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hofbauer GF, Attard NR, Harwood CA, et al. . Reversal of UVA skin photosensitivity and DNA damage in kidney transplant recipients by replacing azathioprine. Am J Transplant. 2012;12(1):218-225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Na R, Laaksonen MA, Grulich AE, et al. . High azathioprine dose and lip cancer risk in liver, heart, and lung transplant recipients: a population-based cohort study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74(6):1144-1152.e6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dantal J, Hourmant M, Cantarovich D, et al. . Effect of long-term immunosuppression in kidney-graft recipients on cancer incidence: randomised comparison of two cyclosporin regimens. Lancet. 1998;351(9103):623-628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Coghill AE, Johnson LG, Berg D, Resler AJ, Leca N, Madeleine MM. Immunosuppressive medications and squamous cell skin carcinoma: nested case-control study within the Skin Cancer after Organ Transplant (SCOT) cohort. Am J Transplant. 2016;16(2):565-573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Campbell SB, Walker R, Tai SS, Jiang Q, Russ GR. Randomized controlled trial of sirolimus for renal transplant recipients at high risk for nonmelanoma skin cancer. Am J Transplant. 2012;12(5):1146-1156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Euvrard S, Morelon E, Rostaing L, et al. ; TUMORAPA Study Group . Sirolimus and secondary skin-cancer prevention in kidney transplantation. N Engl J Med. 2012;367(4):329-339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hoogendijk-van den Akker JM, Harden PN, Hoitsma AJ, et al. . Two-year randomized controlled prospective trial converting treatment of stable renal transplant recipients with cutaneous invasive squamous cell carcinomas to sirolimus. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31(10):1317-1323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ritchie SA, Patel MJ, Miller SJ. Therapeutic options to decrease actinic keratosis and squamous cell carcinoma incidence and progression in solid organ transplant recipients: a practical approach. Dermatol Surg. 2012;38(10):1604-1621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Iannacone MR, Pandeya N, Isbel N, et al. ; STAR Study . Sun protection behavior in organ transplant recipients in Queensland, Australia. Dermatology. 2015;231(4):360-366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ismail F, Mitchell L, Casabonne D, et al. . Specialist dermatology clinics for organ transplant recipients significantly improve compliance with photoprotection and levels of skin cancer awareness. Br J Dermatol. 2006;155(5):916-925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mahé E, Morelon E, Fermanian J, et al. . Renal-transplant recipients and sun protection. Transplantation. 2004;78(5):741-744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rose RF, Moniem K, Seukeran DC, Stables GI, Newstead CG. Compliance of renal transplant recipients with advice about sun protection measures: completing the audit cycle. Transplant Proc. 2005;37(10):4320-4322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Seukeran DC, Newstead CG, Cunliffe WJ. The compliance of renal transplant recipients with advice about sun protection measures. Br J Dermatol. 1998;138(2):301-303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mihalis EL, Wysong A, Boscardin WJ, Tang JY, Chren MM, Arron ST. Factors affecting sunscreen use and sun avoidance in a U.S. national sample of organ transplant recipients. Br J Dermatol. 2013;168(2):346-353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Birkeland SA, Storm HH, Lamm LU, et al. . Cancer risk after renal transplantation in the Nordic countries, 1964-1986. Int J Cancer. 1995;60(2):183-189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hartevelt MM, Bavinck JN, Kootte AM, Vermeer BJ, Vandenbroucke JP. Incidence of skin cancer after renal transplantation in the Netherlands. Transplantation. 1990;49(3):506-509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lindelöf B, Sigurgeirsson B, Gäbel H, Stern RS. Incidence of skin cancer in 5356 patients following organ transplantation. Br J Dermatol. 2000;143(3):513-519. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Adami J, Gäbel H, Lindelöf B, et al. . Cancer risk following organ transplantation: a nationwide cohort study in Sweden. Br J Cancer. 2003;89(7):1221-1227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Moloney FJ, Comber H, O’Lorcain P, O’Kelly P, Conlon PJ, Murphy GM. A population-based study of skin cancer incidence and prevalence in renal transplant recipients. Br J Dermatol. 2006;154(3):498-504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Aberg F, Pukkala E, Höckerstedt K, Sankila R, Isoniemi H. Risk of malignant neoplasms after liver transplantation: a population-based study. Liver Transpl. 2008;14(10):1428-1436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jensen AO, Svaerke C, Farkas D, Pedersen L, Kragballe K, Sørensen HT. Skin cancer risk among solid organ recipients: a nationwide cohort study in Denmark. Acta Derm Venereol. 2010;90(5):474-479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wisgerhof HC, van der Geest LG, de Fijter JW, et al. . Incidence of cancer in kidney-transplant recipients: a long-term cohort study in a single center. Cancer Epidemiol. 2011;35(2):105-111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hortlund M, Arroyo Mühr LS, Storm H, Engholm G, Dillner J, Bzhalava D. Cancer risks after solid organ transplantation and after long-term dialysis. Int J Cancer. 2017;140(5):1091-1101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wisgerhof HC, van der Boog PJ, de Fijter JW, et al. . Increased risk of squamous-cell carcinoma in simultaneous pancreas kidney transplant recipients compared with kidney transplant recipients. J Invest Dermatol. 2009;129(12):2886-2894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Green AC, Olsen CM. Increased risk of melanoma in organ transplant recipients: systematic review and meta-analysis of cohort studies. Acta Derm Venereol. 2015;95(8):923-927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hosseini-Moghaddam SM, Soleimanirahbar A, Mazzulli T, Rotstein C, Husain S. Post renal transplantation Kaposi’s sarcoma: a review of its epidemiology, pathogenesis, diagnosis, clinical aspects, and therapy. Transpl Infect Dis. 2012;14(4):338-345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Moore PS, Chang Y. Detection of herpesvirus-like DNA sequences in Kaposi’s sarcoma in patients with and those without HIV infection. N Engl J Med. 1995;332(18):1181-1185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Liu Y, Sheikh MS. Melanoma: molecular pathogenesis and therapeutic management. Mol Cell Pharmacol. 2014;6(3):228. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bouwes Bavinck JN, Vermeer BJ, van der Woude FJ, et al. . Relation between skin cancer and HLA antigens in renal-transplant recipients. N Engl J Med. 1991;325(12):843-848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kwiek B, Schwartz RA. Keratoacanthoma (KA): an update and review. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74(6):1220-1233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]