Abstract

Importance

Evidence for the long-term efficacy and safety of anti–tumor necrosis factor α agents (anti-TNF) in treating cutaneous sarcoidosis is lacking.

Objective

To determine the efficacy and safety of anti-TNF in treating cutaneous sarcoidosis in a large observational study.

Design, Setting, and Participants

STAT (Sarcoidosis Treated with Anti-TNF) is a French retrospective and prospective multicenter observational database that receives data from teaching hospitals and referral centers, as well as several pneumology, dermatology, and internal medicine departments. Included patients had histologically proven sarcoidosis and received anti-TNF between January 2004 and January 2016. We extracted data for patients with skin involvement at anti-TNF initiation.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Response to treatment was evaluated for skin and visceral involvement using the ePOST (extra-pulmonary Physician Organ Severity Tool) severity score (from 0 [not affected] to 6 [very severe involvement]). Epidemiological and cutaneous features at baseline, efficacy, steroid-sparing, safety, and relapses were recorded. The overall cutaneous response rate (OCRR) was defined as complete (final cutaneous ePOST score of 0 or 1) or partial response (ePOST drop ≥2 points from baseline but >1 at last follow-up).

Results

Among 140 patients in the STAT database, 46 had skin involvement. The most frequent lesions were lupus pernio (n = 21 [46%]) and nodules (n = 20 [43%]). The median cutaneous severity score was 5 and/or 6 at baseline. Twenty-one patients were treated for skin involvement and 25 patients for visceral involvement. Reasons for initiating anti-TNF were failure or adverse effects of previous therapy in 42 patients (93%). Most patients received infliximab (n = 40 [87%]), with systemic steroids in 28 cases (61%) and immunosuppressants in 32 cases (69.5%). The median (range) follow-up was 45 (3-103) months. Of the 46 patients with sarcoidosis and skin involvement who were treated with anti-TNF were included, median (range) age was 50 (14-78) years, and 33 patients (72%) were women. The OCRR was 24% after 3 months, 46% after 6 months, and 79% after 12 months. Steroid sparing was significant. Treatment was discontinued because of adverse events in 11 patients (24%), and 21 infectious events occurred in 14 patients (30%). Infections were more frequent in patients treated for visceral involvement than in those treated for skin involvement (n = 12 of 25 [48%] vs n = 2 of 21 [9.5%], respectively; P = .02). The relapse rate was 44% 18 months after discontinuation of treatment. Relapses during treatment occurred in 35% of cases, mostly during anti-TNF or concomitant treatment tapering.

Conclusions and Relevance

Anti-TNF agents are effective but suspensive in cutaneous sarcoidosis. The risk of infectious events must be considered.

This large multicenter observational study explores the efficacy and safety of anti–tumor necrosis factor α agents in treating cutaneous sarcoidosis.

Key Points

Question

What is the long-term efficacy and safety of anti–tumor necrosis factor α agents (anti-TNF) in treating cutaneous sarcoidosis?

Findings

In this multicenter observational study of 46 patients with sarcoidosis and skin involvement who were treated with anti-TNF, the overall cutaneous response rate was 24% after 3 months, 46% after 6 months, and 79% after 12 months. Eleven (24%) patients stopped anti-TNF because of adverse events, and patients treated for visceral involvement had significantly more infections (48% vs 9.5%), and relapses occurred in half of the patients after discontinuation of anti-TNF.

Meaning

Anti-TNF agents are effective against cutaneous sarcoidosis with a low infectious rate in patients treated for skin involvement.

Introduction

The management of skin sarcoidosis is still based on small trials and case series, mainly because therapeutic strategy depends on visceral prognosis. Limited skin lesions are generally treated with topical steroids, tetracycline antibiotics, or hydroxychloroquine,1 despite a low level of evidence for efficacy. In case of failure or extensive and/or stigmatizing lesions, such as lupus pernio, systemic steroids (SS) and/or immunosuppressive agents (IS) have been shown to be useful.2 Thalidomide is also considered in some patients, despite a negative trial and potential adverse effects.3

High-quality trials demonstrating efficacy of anti–tumor necrosis factor α agents (anti-TNF) for the treatment of severe skin sarcoidosis are few. We investigated the efficacy and tolerance of anti-TNF in 46 patients.

Methods

STAT (Sarcoidosis Treated with Anti-TNF) is a French national voluntary retrospective and prospective database investigating the efficacy and safety of anti-TNF in sarcoidosis. Inclusion criteria in STAT were as follows: diagnosis of histologically proven sarcoidosis made in accordance with the guidelines of the World Association of Sarcoidosis and Other Granulomatous diseases,4 age older than 18 years, and current or previous treatment with anti-TNF. The initiation of anti-TNF therapy in each participating center was decided by the referral physician, according to real-life standard practice. Patients provided written consent for inclusion, and physicians collected the following data: demographics, characteristics of the disease at baseline (ie, initiation of anti-TNF), previous treatments, concomitant SS or IS, and adverse events (AEs). The severity scoring for each organ (including skin) used the ePOST (extra-pulmonary Physician Organ Severity Tool) ranging from 0 (not affected) to 6 (very severe involvement).5

All patients with skin involvement at baseline were included in the present study. The primary end point was the overall cutaneous response rate (OCRR) to anti-TNF at 3, 6, and 12 months; complete response was defined as a cutaneous ePOST score 0 or 1 and partial response was defined as a decrease or 2 or more points from baseline. Secondary objectives included AEs, steroid sparing, and relapses.

Categorical variables were compared using the χ2 test and continuous variables were compared using the Wilcoxon rank sum test. We first assessed efficacy and safety in the whole cohort and then compared patients with a skin-only indication for anti-TNF (Group 1) and patients treated for visceral involvement (Group 2). The response rates and infections, according to the duration of exposure, were described by Kaplan-Meier analysis. Univariate analyses of the predictor of response and infection were conducted using the log-rank test. All tests were 2-sided, and a P value less than .05 was considered significant. Analyses were performed using R statistical software, version 3.2.2 (R Foundation) for χ2 analyses and Stata 14.0 (StataCorp LLC) for log-rank analyses.

In France, observational studies that do not change routine patient management do not require ethics committee or institutional review board approval; all patients included in the STAT database provided informed consent.

Results

Forty-six patients of 140 included in the STAT database had skin lesions (Table). A total of 66 individual courses of anti-TNF were administrated (14 patients received more than 1 course). Anti-TNF were administered with SS (mean dose of prednisone of 17.5 mg/d) in 28 cases (61%) and IS (methotrexate n = 26) in 32 cases (69.5%). Group 1 consisted of 21 patients; Group 2, 25 patients. The median (range) follow-up was 45 (3-109) months.

Table. Characteristics of the 46 Patients at Baseline.

| Characteristic | No. (%) |

|---|---|

| Age, median (range), y | 50 (14-78) |

| Women, No. (%) | 33 (72) |

| Disease duration, median (range), y | 10 (1.3-33) |

| Geographical origin, No. (%) | |

| Caucasian | 14 (30) |

| Northern African | 14 (30) |

| Caribbean | 9 (20) |

| African | 6 (13) |

| Organs involved, No. (%) | |

| Skin | 46 (100) |

| Lungs | |

| Asymptomatic | 28 (61) |

| Symptomatic | 8 (20) |

| Joints | 14 (30) |

| Ear, nose, and throat | 13 (28) |

| Heart | 8 (20) |

| Central nervous system | 7 (17) |

| Liver | 7 (17) |

| Eye | 5 (11) |

| Organs involved, median (range) | 3 (1-8) |

| Type of cutaneous lesions | |

| Lupus pernio | 21 (46) |

| Nodules (small and large) | 20 (43) |

| Plaques | 11 (24) |

| Subcutaneous lesions | 3 (6) |

| Alopecia | 3 (6) |

| Localization, No. (%) | |

| Face and neck | 33 (69) |

| Trunk and limbs | 22 (48) |

| Cutaneous ePOST, median (range) | 5 (1-6) |

| Previous treatment, No.(%) | |

| Methotrexate | 39 (85) |

| Prednisone | 35 (76) |

| Hydroxychloroquine | 27 (59) |

| Azathioprine | 14 (30) |

| Thalidomide | 10 (22) |

| Tetracycline | 7 (15) |

| Other | 18 (39) |

| Prior immunosuppressive agents, median (range) | 1.7 (0-4) |

| Main indication for anti-TNF, No. (%) | |

| Severe disease | 38 (83) |

| Previous treatment failure | 42 (93) |

| Previous adverse effects | 23 (50) |

| Steroid-dependent disease | 11 (24) |

| Type of anti-TNF used as first line, No. (%) | |

| Infliximab (various regimen) | 40 (87) |

| Adalimumab | 5 (11) |

| Etanercept | 1 (2) |

Abbreviation: anti-TNF, anti–tumor necrosis factor α agents.

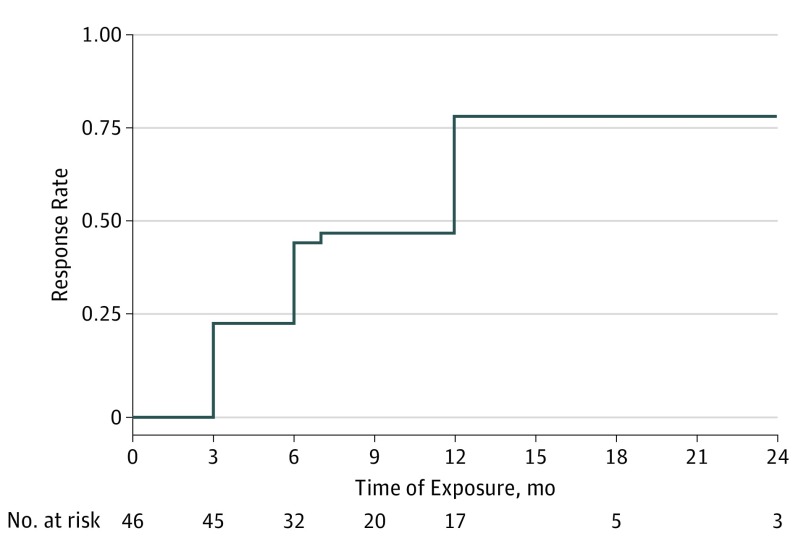

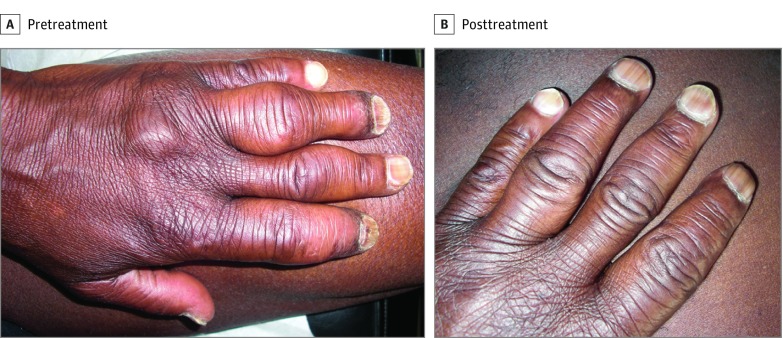

Overall cutaneous response rate is presented in Figure 1, and Figure 2 shows an example of a complete cutaneous response. The mean dose of SS decreased from 17.5 mg/d at baseline to 8.4 mg/d at the last follow-up (P < .001).

Figure 1. Cutaneous Response to Anti–Tumor Necrosis Factor α Agents.

The overall cutaneous response rate was 24% (95% CI, 14%-40%) after 3 months, 46% (95% CI, 32%-62%) after 6 months, and 79% (95% CI, 64%-98%) after 12 months. Median ePOST severity score decreased from 5 at baseline to 3 at the last follow-up. Among a total of 31 responders, 13 achieved complete response and 18 achieved partial response as best response during follow-up.

Figure 2. Response to Infliximab.

Clinical photographs of a patient with large subcutaneous nodules of the fingers show complete response to infliximab.

In univariate analysis, OCRR was associated with nodules but not with other lesions (lupus pernio, plaques), age, sex, or duration of the disease.

Fourteen patients (30%) experienced 21 infectious AEs: urinary tract infections (n = 6), bronchopneumonitis (n = 7), sinusitis (n = 2), dental abscess, cellulitis, angiocholitis, herpes zoster, flu, and gastroenteritis (n = 1 for each). Seven patients (50%) were hospitalized for infection (grade 3/4): pneumonitis (n = 3), urinary tract infection, herpes zoster, facial cellulitis, and angiocholitis (n = 1 for each). Treatment was discontinued in 4 patients (3 for pneumonitis and 1 for facial cellulitis) and a patient in his 80s treated with concomitant prednisone of 40 mg/d and azathioprine died of pneumonitis. Thirteen of 14 patients who experienced infections were receiving SS and/or IS.

Sixteen patients with response stopped treatment (10 for AE; 6 for remission); 8 of these patients relapsed with a relapse rate of 20% at 1 year and 44% at 18 months. Treatment was resumed for 5 patients who had achieved previous remission with a response rate of 100%. Ten patients stopped first-line anti-TNF because of failure. Five patients received a second anti-TNF with efficacy in 3 cases.

Among 31 patients who responded to anti-TNF, 11 patients (35%) relapsed during treatment. Relapse occurred for 8 patients during dose spacing or reduction of anti-TNF (n = 3) or tapering of the concomitant SS (n = 3) or IS (n = 2). The outcome was favorable for 8 patients upon resumption of the prior treatment, shortening of the dosing interval, and/or increasing the dose of steroids. Anti-TNF was definitively discontinued in the other 3 patients.

By comparing groups, cutaneous ePOST scores at baseline were higher in Group 1 (5 vs 3; P < .001). Patients were treated with more concomitant SS (18 [76%] vs 7 [33%]; P = .003) and IS (21 [84%] vs 11 [53%]; P = .02) in Group 2, but OCRR was not different (13 [62%] in Group 1 and 19 [72%] in Group 2; P = .67). Infections were more frequent in Group 2: 12 of 25 patients (48%) vs 2 of 21 patients (9.5%) (P = .02). In univariate analysis, age, sex, SS before baseline, associated IS, or associated SS were not associated with infections.

Discussion

This large multicenter observational study showed that: (1) anti-TNF agents were effective in treating cutaneous sarcoidosis with an OCRR of 46% at 6 months and 79% at 12 months after the initiation of treatment; (2) anti-TNF had a significant steroid-sparing effect; (3) in total, 11 patients (24%), among whom one died, had to stop anti-TNF due to AEs (5 being infectious); (4) 14 of 46 patients (30%) experienced infections of varying severity, especially patients from Group 2 compared with Group 1 (n = 12 of 25 [48%] vs n = 2 of 21 [9.5%], respectively); (5) relapses occurred in almost half of the patients after discontinuation, but all patients in whom anti-TNF was discontinued because of remission achieved remission again upon resuming anti-TNF.

In our study, we showed similar OCRR as previous studies.6,7,8,9,10 Response was rather slow. In the literature, infliximab and adalimumab are the most effective anti-TNF in sarcoidosis, but questions remain regarding dose and duration of therapy. In our series, anti-TNF had a suspensive effect. Expert consensus on the use of anti-TNF for the treatment of sarcoidosis has recommended gradually prolonging the interval between injections before discontinuing anti-TNF to limit the risk of relapses.11

We found more infections in patients of Group 2, who received more SS and IS.

There is little consensus in the literature on the increased risk of infection with anti-TNF treatment when used in combination with SS and/or IS vs monotherapy. Similar rates of infection were observed in the treatment of inflammatory bowel diseases in randomized clinical trials12 and reports to the US Food and Drug Administration,13 but a clear increased risk of infection with combination therapy has been described in observational studies.14,15

Limitations

Limitations were the volunteer inclusion in STAT, heterogeneous severity of cases, and unknown reproducibility of ePOST for skin lesions. However, the ePOST score was the simplest tool to evaluate severity and response in all organs. Adverse effects could have been underreported.

Conclusions

Anti-TNF agents are effective in cutaneous sarcoidosis, but relapses are frequent after discontinuation. Clinicians must be aware of infections, especially if patients are being treated with concomitant SS or IS.

References

- 1.Jones E, Callen JP. Hydroxychloroquine is effective therapy for control of cutaneous sarcoidal granulomas. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1990;23(3 Pt 1):487-489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baughman RP, Lower EE. Evidence-based therapy for cutaneous sarcoidosis. Clin Dermatol. 2007;25(3):334-340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Droitcourt C, Rybojad M, Porcher R, et al. A randomized, investigator-masked, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial on thalidomide in severe cutaneous sarcoidosis. Chest. 2014;146(4):1046-1054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hunninghake GW, Costabel U, Ando M, et al. ATS/ERS/WASOG statement on sarcoidosis. American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society/World Association of Sarcoidosis and other Granulomatous Disorders. Sarcoidosis Vasc Diffuse Lung Dis. 1999;16(2):149-173. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Judson MA, Baughman RP, Costabel U, et al. ; Centocor T48 Sarcoidosis Investigators . Efficacy of infliximab in extrapulmonary sarcoidosis: results from a randomised trial. Eur Respir J. 2008;31(6):1189-1196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pariser RJ, Paul J, Hirano S, Torosky C, Smith M. A double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial of adalimumab in the treatment of cutaneous sarcoidosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;68(5):765-773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Baughman RP, Judson MA, Lower EE, et al. ; Sarcoidosis Investigators . Infliximab for chronic cutaneous sarcoidosis: a subset analysis from a double-blind randomized clinical trial. Sarcoidosis Vasc Diffuse Lung Dis. 2016;32(4):289-295. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stagaki E, Mountford WK, Lackland DT, Judson MA. The treatment of lupus pernio: results of 116 treatment courses in 54 patients. Chest. 2009;135(2):468-476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sené T, Juillard C, Rybojad M, et al. Infliximab as a steroid-sparing agent in refractory cutaneous sarcoidosis: single-center retrospective study of 9 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;66(2):328-332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Russell E, Luk F, Manocha S, Ho T, O’Connor C, Hussain H. Long term follow-up of infliximab efficacy in pulmonary and extra-pulmonary sarcoidosis refractory to conventional therapy. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2013;43(1):119-124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Drent M, Cremers JP, Jansen TL, Baughman RP. Practical eminence and experience-based recommendations for use of TNF-α inhibitors in sarcoidosis. Sarcoidosis Vasc Diffuse Lung Dis. 2014;31(2):91-107. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jones JL, Kaplan GG, Peyrin-Biroulet L, et al. Effects of concomitant immunomodulator therapy on efficacy and safety of anti-tumor necrosis factor therapy for Crohn’s disease: a meta-analysis of placebo-controlled trials. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;13(13):2233-2240.e1-2;quiz e177-178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Deepak P, Stobaugh DJ, Ehrenpreis ED. Infectious complications of TNF-α inhibitor monotherapy versus combination therapy with immunomodulators in inflammatory bowel disease: analysis of the Food and Drug Administration Adverse Event Reporting System. J Gastrointestin Liver Dis. 2013;22(3):269-276. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Toruner M, Loftus EV Jr, Harmsen WS, et al. Risk factors for opportunistic infections in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterology. 2008;134(4):929-936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fidder H, Schnitzler F, Ferrante M, et al. Long-term safety of infliximab for the treatment of inflammatory bowel disease: a single-centre cohort study. Gut. 2009;58(4):501-508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]