Key Points

Question

Can store-and-forward teledermatology improve access to dermatological health care?

Findings

Compared with traditional in-person dermatology referrals, teledermatology reduced the medial time to evaluation and time to treatment. After teledermatology was introduced, a greater overall percentage of patients referred to dermatology were actually evaluated by a dermatologist (83.3%) compared with the previous year (64.2%). Primary care physicians followed management recommendations 93% of the time.

Meaning

Teledermatology can improve access to dermatologic care in a public safety-net hospital setting.

Abstract

Importance

External store-and-forward (SAF) teledermatology systems operate separately from the primary health record and have many limitations, including care fragmentation, inadequate communication among clinicians, and privacy and security concerns, among others. Development of internal SAF workflows within existing electronic health records (EHRs) should be the standard for large health care organizations for delivering high-quality dermatologic care, improving access, and capturing other telemedicine benchmark data. Epic EHR software (Epic Systems Corporation) is currently one of the most widely used EHR system in the United States, and development of a successful SAF workflow within it is needed.

Objectives

To develop an SAF teledermatology workflow within the Epic system, the existing EHR system of Parkland Health and Hospital System (Dallas, Texas), assess its effectiveness in improving access to care, and validate its reliability; and to evaluate the system’s ability to capture meaningful outcomes.

Design, Setting, and Participants

Electronic consults were independently evaluated by 2 board-certified dermatologists, who provided diagnoses and treatment plans to primary care physicians (PCPs). Results were compared with in-person referrals from May to December 2013 from the same clinic (a community outpatient clinic in a safety-net public hospital system). Patients were those 18 years or older with dermatologic complaints who would have otherwise been referred to dermatology clinic.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Median time to evaluation; percentage of patients evaluated by a dermatologist through either teledermatology or in-person compared with the previous year.

Results

Seventy-nine teledermatology consults were placed by 6 PCPs from an outpatient clinic between May and December 2014; 57 (74%) were female and their mean (SD) age was 47.0 (12.4) years. Teledermatology reduced median time to evaluation from 70.0 days (interquartile range [IQR], 33.25-83.0 days) to 0.5 days (IQR, 0.172-0.94 days) and median time to treatment from 73.5 to 3.0 days compared with in-person dermatology visits. Overall, a greater percentage of patients (120 of 144 [83.3%]) were evaluated by a dermatologist through either teledermatology or in-person during the 2014 study period compared with the previous year (111 of 173 [64.2%]). Primary care physicians followed management recommendations 93% of the time.

Conclusions and Relevance

Epic-based SAF teledermatology can improve access to dermatologic care in a public safety-net hospital setting. We hope that the system will serve as a model for other health care organizations wanting to create SAF teledermatology workflows within the Epic EHR system.

This pilot study describes a store-and-forward teledermatology workflow within an existing electronic health record system, assesses its effectiveness in improving access to care, validates its reliability, and evaluates its ability to capture meaningful outcomes.

Introduction

Teledermatology is an increasingly popular modality for expanding dermatologic care to underserved populations. Store-and-forward (SAF) and live-interactive are the 2 main types of teledermatology, but owing to lower costs and flexible timing, SAF is the most popular. Unfortunately, systems such as the American Academy of Dermatology’s (AAD) AccessDerm function separately from the primary health record. These external systems have many limitations, including care fragmentation, inadequate communication between clinicians, privacy and security concerns, and difficulty in billing, among others. Internal SAF systems offer many advantages over external ones, including maintenance of records within one system, better continuity of care, and improved access to clinical patient medical records, that can help teledermatologists make more accurate diagnoses. In addition, internal systems can be used to track quality benchmark data more effectively. For these reasons, development of SAF teledermatology workflows within existing electronic health records (EHRs) should be the standard for large health care organizations for delivering quality dermatologic care, improving access, and capturing other telemedicine quality benchmark data, which will continue to grow in importance owing to Medicare Quality Payment Program reporting requirements. Unfortunately, aside from the Veterans Affairs system, which performs SAF teledermatology using the Computerized Patient Record System, little has been published regarding SAF teledermatology workflows using a health care organization’s existing EHR system in the United States.

We sought to create an internal SAF teledermatology workflow using Epic EHR software (Epic Systems Corporation), the existing EHR program for Parkland Health and Hospital System (PHHS), the safety-net public health system of Dallas County in Texas (population approximately 2.5 million). Approximately 5000 referrals to the Parkland Dermatology Clinic are made from 12 community outpatient clinics each year. The average wait time for new patients in the dermatology clinic was 67 days over the past 3 years, with a mean of 59 days for follow-up appointments. The clinic’s no-show rate is approximately 31% overall and 35% for new patients.

Our primary goal was to improve access to dermatologic care by developing an SAF teledermatology system using the Epic system. We also sought and evaluated the system’s efficacy, reliability, and ability to capture meaningful patient outcomes. Finally, because the Epic system is currently the most popular EHR software program in the United States, used by over 350 health care organizations, including 28 000 clinics and 1580 hospitals, we hope to serve as a model for other health care organizations wanting to create SAF teledermatology workflows within existing Epic EHRs.

Methods

SAF Teledermatology Workflow

To provide secure access for primary care physicians (PCPs), we developed an SAF workflow within Epic EHR. Each physician and staff member received 2 hours of training consisting of lectures and hands-on experience with the EPIC workflow and photography. We modified the AAD AccessDerm teledermatology questionnaire, which included patient demographics, duration of the condition, symptoms, distribution, alleviating and exacerbating factors, previous treatments, relevant medical history, and history of skin cancer. Our form also requested that the PCP give the most likely diagnosis and next scheduled follow-up.

Within the Epic system, the PCP completes the questionnaire, and clinical photographs are taken by clinic staff. The “e-consult” is sent to the pool of teledermatologists consisting of dermatologists at Parkland Hospital, who review the questionnaires and clinical images. Once the teledermatologist accepts the consult, a separate e-consult encounter is created in the patient’s EHR. The teledermatologist reviews the submitted history and clinical images from within the opened encounter. They may also review the patient’s medical record for past clinical notes, previously prescribed medications, and laboratory test results that may also be helpful. The teledermatologist provides an International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, Tenth Revision (ICD-10), diagnosis if able, as well as treatment and triage recommendations. The teledermatologist also has access to order-entry to prescribe medications typically limited to dermatology in Parkland’s system, such as high-potency steroids or topical tacrolimus. The completed response is sent back to the PCP’s Epic In-basket as well as the dermatology clinic’s referral coordinator if an in-person clinic visit was recommended. The questionnaire and related images are linked together with the teledermatologist’s response under the e-consult encounter that was created.

The PCP then reviews the incoming message, replies if there are questions, prescribes recommended medications, and contacts the patient either through a telephone encounter or through the electronic MyChart application. If an in-person dermatology clinic visit is recommended by the teledermatologist, the PCP places a dermatology referral, which is expedited by the dermatology clinic referral coordinator.

Evaluation of Effectiveness and Reliability of the Program

Patients were selected by PCPs at the Southeast Dallas Health Center, 1 of the 12 PHHS community outpatient health centers. This clinic was chosen because it was among the largest outpatient clinics, had a high volume of referrals, and expressed interest in the pilot study. The PCPs were instructed to select patients for teledermatology consults who would have been otherwise referred for in-patient dermatology visits. Inclusion criteria included an age of at least 18 years and with a dermatologic complaint of erythematous eruptions, nonmelanocytic skin neoplasms, wounds, alopecia, or other skin conditions. Exclusion criteria included melanocytic lesions and dermatological emergencies, because these patients were referred for in-person consultation or sent to the emergency department, respectively. Melanocytic lesions were excluded because previous studies have demonstrated that SAF teledermatology cannot be reliably used to rule out melanoma without the use of teledermoscopy. Verbal informed consent and Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) authorization were obtained from patients. They were not compensated for their participation. The University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center institutional review board approved this study as a quality improvement project.

Data Collection

Teledermatology consults were placed between May and December 2014. These data were compared with traditional, in-person referrals from the same clinic during the same interval from the previous year (May to December 2013), as well as direct in-person referrals placed during the study interval. Using retrospective medical record review, we compared the demographic, diagnostic, and clinical management data of the 3 groups.

For the first aim (improving access to care), we hypothesized that a greater percentage of patients would be evaluated by a dermatologist through either teledermatology or in-person compared with the previous year. We also recorded time to evaluation by a dermatologist, time to definitive treatment, and number of patients evaluated by a dermatologist. A patient was considered to be evaluated by a dermatologist when an e-consult was completed by a teledermatologist or a dermatology clinic visit was documented in the EHR. In the teledermatology arm, time to evaluation started at the time of the PCP’s electronic signature on the teledermatology consult and ended when the response was electronically signed, excluding weekends and holidays. For traditional referrals, this was measured from referral placement to in-person evaluation in the dermatology clinic.

We calculated time to definitive treatment, which was measured from the teledermatology consult or referral placement to time of definitive treatment, defined as medication prescription, procedure completion, education completion, or referral placement. For teledermatology cases in which an in-person evaluation was recommended, time to treatment was defined as the time between the teledermatology consult to when the patient received definitive treatment in the dermatology clinic.

For the second aim, the reliability of teledermatology was evaluated by having 2 board-certified dermatologists (B.F.C. and A.R.D.) respond independently to each e-consult and include a differential diagnosis and management recommendation. Each diagnosis was then classified into categories modeled after previous studies (Table 1). Concordance of each diagnosis and treatment group was then determined by 2 of us (Z.A.C. and A.R.D.) using criteria from the same studies.

Table 1. Demographic Characteristics and Disease Categories of Patients Referred Through Teledermatology or In-Patient Clinic Visits.

| Characteristic | 2013 Traditional In-Person Referrals (n = 173) |

2014 Teledermatology Patients (n = 79) |

2014 Traditional In-Person Referrals (n = 65) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Female, No. (%) | 116 (67) | 57 (72) | 42 (65) |

| Race/ethnicity | |||

| White Hispanic | 59 (34) | 46 (58) | 23 (35) |

| White non-Hispanic | 53 (31) | 11 (14) | 24 (37) |

| Black | 57 (33) | 20 (25) | 18 (28) |

| Asian | 4 (2) | 2 (3) | 0 |

| Age, mean (SD), y | 47.0 (12.4) | 44.0 (11.5) | 50.2 (11.8) |

| Healthcare coverage, No. (%) | |||

| Medicare | 8 (5) | 3 (4) | 4 (6) |

| Medicaid | 10 (6) | 6 (8) | 4 (6) |

| Dallas county PFAa | 139 (80) | 62 (78) | 54 (83) |

| Federal, state, or local women’s or children’s health program | 3 (2) | 3 (4) | 0 |

| Private insurance | 5 (3) | 1 (1) | 0 |

| Combination, any + partial PFAb | 6 (3) | 4 (5) | 3 (5) |

| Self-pay | 2 (1) | 0 | 0 |

| Disease category, No. (%) | |||

| Eczematous conditions | 21 (12) | 27 (34) | 9 (14) |

| Papulosquamous | 10 (6) | 10 (13) | 9 (14) |

| Benign tumors/proliferations | 26 (15) | 7 (9) | 9 (14) |

| Pigmented lesions | 5 (3) | 1 (1) | 5 (8) |

| Premalignant/malignant | 12 (7) | 3 (4) | 3 (5) |

| Acneiform/follicular | 9 (5) | 7 (9) | 2 (3) |

| Alopecia | 8 (5) | 6 (8) | 0 |

| Pigmentation disorders | 6 (3) | 7 (9) | 3 (5) |

| Infectious diseases | 9 (5) | 6 (8) | 0 |

| Other | 5 (3) | 5 (6) | 5 (8) |

| Not evaluated | 62 (36) | 0 | 20 (30) |

Abbreviations: PFA, Parkland Financial Assistance; PHHS, Parkland Health and Hospital System.

PFA is a Dallas County tax payer–funded program that provides residents full financial assistance for their health care services within PHHS. Patients must qualify based on information such as income and household size.

Insured patients earning less than 200% of the Federal Poverty Guidelines are eligible for partial assistance through PFA, helping to reduce deductibles and copayments

For the final aim, we recorded the number of cases in which teledermatology recommendations were followed by the PCP, including medications prescribed, referrals placed, and documentation of recommendations from teledermatology. We also reviewed the EHR for patient outcomes up to 1 year after completion of the study. Follow-up visit notes from the PCP or dermatologist were reviewed for patient- or physician-reported improvement, stability, or worsening. Finally, we reviewed the medical records of both groups to determine whether teledermatology prevented emergency department visits, additional PCP visits or hospital admissions related to the dermatology referral that might have occurred prior to the patient receiving definitive treatment, either through teledermatology or in dermatology clinic.

Statistical Analysis

Because this was a pilot study, no sample size was calculated. Frequencies and percentages were calculated for categorical variables, whereas continuous variables were summarized as median and 25th to 75th percentile given the distribution of the data set. Comparisons between teledermatology and traditional referral groups were performed using Mann-Whitney test for continuous variables. One-sided proportions tests with a Yates correction factor were also performed to compare concordances between the clinicians’ diagnoses and management recommendations (concordance definitions are listed in the Table 2 footnotes). Expected concordance rates were assigned based on previously published studies. P <.05 was deemed significant. Finally, we used a 2-sided Fisher exact test to determine whether teledermatology resulted in fewer emergency department visits, PCP visits, or hospital admissions.

Table 2. Diagnostic and Management Concordance Between PCPs, Teledermatologists, and In-Clinic Dermatologists.

| Concordance Comparison (Total No. of Cases Compared) | Discordant, No. (%) of Cases | Partially Concordant Level 1, No. (%) of Casesa,b |

Partially Concordant Level 2, No. (%) of Casesa,b |

Completely Concordant, No. (%) of Cases | Observed Concordance (Partial 1 and 2 and Completely), No. (%) of Cases | Expected Concordance (Partial 1 and 2 and Completely), %c | 1-Sided P Value Using Yates Correction (95% CI)d |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PCP vs tele 1 diagnosis (79) | 49 (62) | 9 (11) | 10 (13) | 11 (14) | 30 (38) | 68 | >.99 (27-49) |

| Tele 1 vs tele 2 diagnosis (79) | 0 | 10 (13) | 44 (56) | 25 (32) | 79 (100) | 88 | .001 |

| Tele 1 vs derm clinic diagnosis (29) | 3 (10) | 5 (17) | 10 (35) | 11 (38) | 26 (90) | 67 | .008 (79-100) |

| PCP vs tele 1 management (79) | 44 (56) | 8 (10) | 23 (29) | 4 (5) | 35 (44) | 61 | .99 (33-55) |

| Tele 1 vs tele 2 management (79) | 12 (15) | 4 (5) | 33 (42) | 30 (38) | 67 (85) | 75 | .03 (77-93) |

Abbreviations: Derm, in-person dermatologist; PCP, primary care physician; tele, teledermatologist.

Diagnostic concordance: Discordant, no agreement or differential diagnosis not provided. Partially concordant level 1, agreement between at least 1 but not all diagnoses. Partially concordant level 2, agreement between diagnostic categories only (from Table 1). Concordant, full agreement.

Management concordance: Discordant, no agreement or management plan not provided. Partially concordant level 1, partial agreement with 1 category of change only. Partially concordant level 2, partial agreement with more than 1 category of change. Concordant, full agreement.

Expected concordance percentage was assigned based on previously published studies.

One-sample proportions tests using a Yates correction were performed to compare observed vs expected concordances between the physicians’ diagnoses and management recommendations. Probability that event was larger than expected [null hypothesis]. A 1-sided P value <.05 was considered significant. Bold font indicates statistical significance.

Results

Patient Characteristics, Referral Patterns, and Access to Care

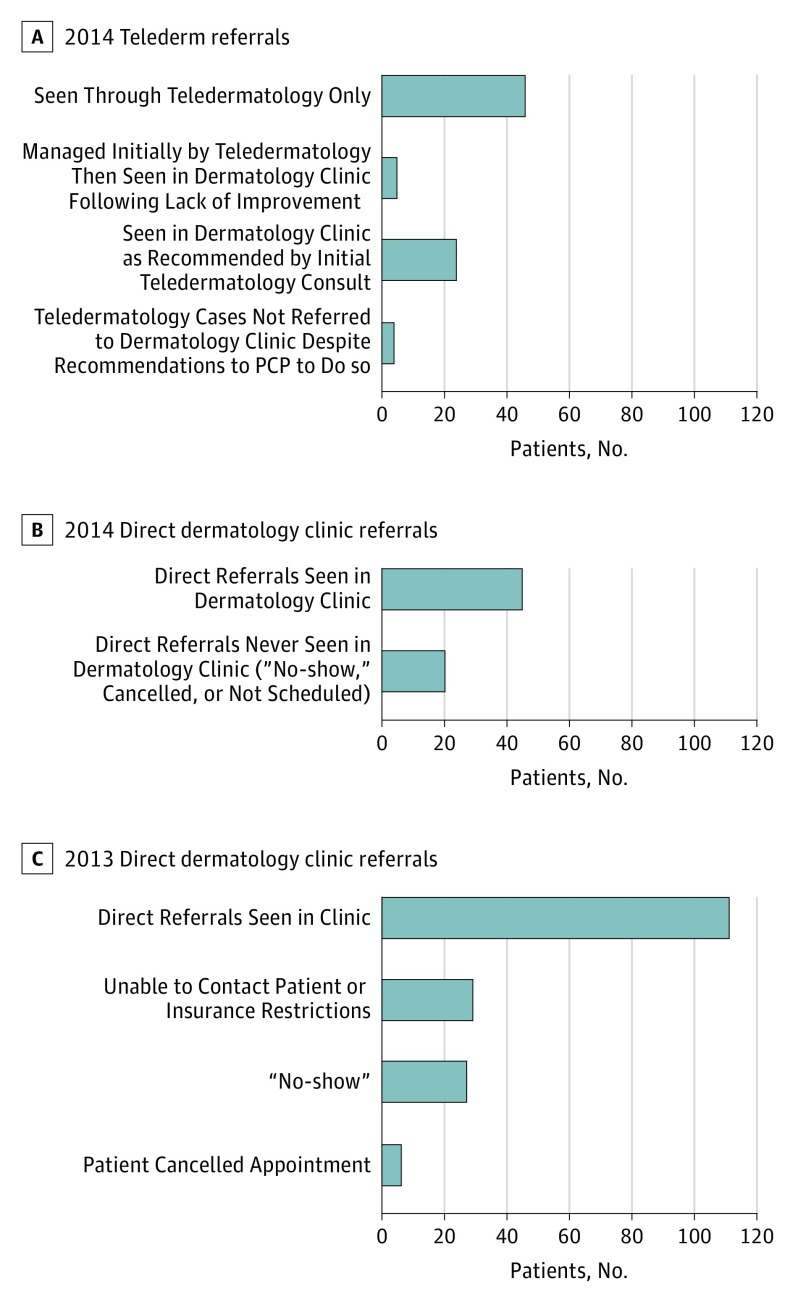

During an 8-month period in 2014, 79 teledermatology consults were placed by 6 PCPs from 1 outpatient clinic; 57 (74%) were female, and their mean (SD) age was 47.0 (12.4) years. The 6 full-time PCPs who received training varied in their adoption of teledermatology, ranging from 5% (1 of 22 consults via teledermatology) to 96% (23 of 24) (median, 55.9%). During the same period, 65 patients were referred by PCPs directly for in-person dermatology clinic visits rather than through teledermatology. Overall, there were 144 patients referred to dermatology from Southeast Dallas Health Center during the study period. In comparison, 171 patients were referred to dermatology clinic over the same 8-month period in 2013 (Figure). Patients referred through teledermatology in 2014 and traditional referrals in 2013 had similar demographics (Table 1). Most teledermatology referrals were for eczematous conditions, while most traditional referrals were for benign tumors or proliferations. In all 3 groups, patients were most often funded by Parkland Financial Assistance, the Dallas County tax payer–supported program providing low-income residents full financial assistance for their health care services within PHHS.

Figure. Outcomes of Referrals From Southeast Dallas Health Center to the Dermatology Clinic During 2013 and the Study Year, 2014.

A, Fifty-one of 79 teledermatology patients (64.6%) were initially treated by teledermatology alone, although 5 patients were subsequently referred to the dermatology clinic after failing to improve with initial treatment. In total, 33 teledermatology patients were referred to the dermatology clinic with 4 not being seen because they improved with treatment, could not be contacted, or were treated by the primary care physician. B, During the study period, 65 patients were also referred to dermatology clinic directly rather than through teledermatology. Forty-five (69.2%) were subsequently seen in clinic. Altogether, 120 of 144 patients (83.3%) were evaluated by dermatologists either through teledermatology or in clinic during the 2014 study period. C, One hundred eleven of 173 patients (64.2%) referred to the dermatology clinic during the same period in 2013 were evaluated by dermatologists. Twenty-nine patients (17%) were not scheduled owing to inability to contact or insurance restrictions; 27 (16%) were no-shows, and 6 (3%) canceled their appointments. The bars indicate standard error.

Overall, a greater percentage of patients (83.3%; 120 of 144) was evaluated by a dermatologist through either teledermatology or in-person during the 2014 study period compared with the previous year (64.2%; 111 of 173) (Figure). For teledermatology, the median time to evaluation was 0.5 days (interquartile range [IQR], 0.2-0.9 days) compared with 70 days (IQR, 33.2-83.0 days) for in-person referrals during the previous year (P < .001). Even when including the 65 patients referred through the traditional method during the study period, the time for evaluation for all patients (either through teledermatology or in-person) originating from the study clinic was significantly less compared with the previous year (median, 1.0 vs 70.0 days; P < .001). Next, we sought to determine whether teledermatology had an impact on time to definitive treatment. The median time to treatment was 3.0 days (IQR, 1.0-35.5 days) for teledermatology, and 73.5 days for in-person referrals for the year prior (IQR, 38.2- 111.5 days). During the study period, time to definitive treatment for all patients, including both teledermatology and in-person visits, was also significantly less compared with the previous year (36.0 vs 74.8 days; P < .001).

Reliability: Concordance Between Clinicians

Diagnostic concordance between 2 teledermatologists was at least partially concordant (levels 1 and 2) in 79 of 79 cases (100%); 67 of 79 cases of management recommendations (85%) were at least partially concordant. For the patients referred through teledermatology and subsequently seen in the dermatology clinic, we compared the diagnoses between the teledermatologists and the in-person dermatologist. Twenty-six of 29 (89.7%) were concordant or partially concordant. The concordance between PCP and teledermatologist diagnoses and management plans was likewise evaluated, with 30 of 79 diagnoses (38.0%) classified as concordant or partially concordant, and 35 of 79 of management recommendations (39.0%) classified as concordant or partially concordant. (Table 2). Comparisons of the observed proportions of partial or complete concordance to the expected level of concordance were significant for all comparisons except PCP vs teledermatologist diagnosis and management, respectively (Table 2).

Capture of Outcomes: Follow-up

For teledermatology consults, the teledermatologist recommended prescription medications for 59 of 79 cases (74.7%). The summary of treatment recommendations is listed in Table 3. The PCP adherence to recommendations was documented in 55 of 59 cases (93.0%) through either electronic prescriptions and telephone encounters. In 4 of 33 cases (5.6%) that were referred to the dermatology clinic for in-person evaluation, the PCP did not carry out this recommendation because the patients improved with treatment, could not be contacted, or were treated by the PCP. Long-term outcome data were not recorded by the PCP in 61 of 79 cases (77.0%). Of those cases for which outcome data were documented, 13 of 18 patients (72%) had either self-reported or physician-assessed improvement at their subsequent clinical encounter.

Table 3. Primary Treatment Categories for 79 Patients Referred by Teledermatology.

| Treatment Categorya | 2014 Teledermatology, No. (%) |

|---|---|

| Education and/or observation | 6 (8) |

| Medication initiation/discontinuation | 59 (74) |

| Laboratory testing | 3 (4) |

| Procedural interventionb | 11 (14) |

| Referral to other service | 0 |

| Change in medication dosage or vehicle | 0 |

Most treatment recommendations included some form of education; however, category was assigned according to the primary recommendation given.

Procedural interventions included biopsy, intralesional steroid injection, and incision and drainage. The need for biopsy was always associated with a recommendation to refer to dermatology, while the steroid injection and incision and drainage allowed for the primary care physician to perform in clinic if able.

During the 2013 traditional referral period, there was 1 visit to the emergency department, 8 additional PCP visits, and no hospital admissions related to the dermatologic referral that occurred prior to the patients being seen in dermatology clinic. Conversely, in the 2014 teledermatology group, there was 1 visit to the emergency department but no additional PCP visits or hospital admissions related to the teledermatology referrals prior to definitive treatments being rendered either through teledermatology or in dermatology clinic if in-person visits were recommended. These differences were not statistically significant (P = .44).

Discussion

This is a pilot study describing the implementation of an SAF teledermatology system in a large safety-net public health and hospital system using an existing Epic system. The most notable accomplishment of this pilot study was the development of a functioning SAF teledermatology workflow within the Epic system, the existing EHR program at PHHS. We demonstrated that our Epic-based SAF teledermatology system improved access to dermatologic care by decreasing the wait time to evaluation, decreasing time to treatment of skin diseases, and increasing the percentage of referred patients evaluated by a dermatologist. In addition, we demonstrated reliability given the excellent diagnostic concordance (100%) between the 2 teledermatologists, with few discordant cases on in-person evaluation, findings similar to those of previously published studies.

Because Epic software is currently the most popular EHR system in the United States, there is great potential for replicating our system and expanding SAF teledermatology to other health care organizations currently using Epic software. Like all SAF teledermatology workflows, the success of our Epic-based system was most dependent on the creation of an organizational framework consistent with the AAD’s teledermatology guidelines. From a technical and software standpoint, our system can be easily replicated at other institutions that use Epic software at a reasonable cost, with the main expense coming from increased server space requirements for images as well as salary for the local Epic analyst implementing the SAF code. Currently, institutions wishing to implement SAF teledermatology within Epic must rely on their local software analysts for programming. Although our system’s code can easily be duplicated by other organizations, Epic would benefit from having its national software developers make SAF teledermatology standard system-wide.

Recent advancements within the Epic system allow for increased utility of the program, including clinical photography using the Epic Haiku smartphone application, which allows authorized users of Epic’s EHR system to take and upload clinical photographs to the patient’s EHR.

Another advantage of our integrated system within EPIC is the ability to capture outcome data, such as time to evaluation and treatment, as well also other, more-difficult-to-capture outcomes, such as adherence to treatment recommendations, prescription fill rates, and response to treatment. In our study, nearly all of the patients were eventually seen for a follow-up visit with their PCP. Unfortunately, most of the clinicians did not record the status of the dermatologic problem at the return visit. In designing the study, we attempted to mimic the typical clinic workflow and did not require that PCPs provide clinical outcome documentation. Future projects will be directed toward capturing more outcome data using interventions, such as automated notifications to PCPs when patients previously evaluated via e-consult return for follow-up visits.

Overall, the ability to track recommendations within the Epic system has the potential to improve the efficiency of the health system. Of the patients for whom a clinic evaluation was recommended, only 4 were not referred. Of these 4, 3 were treated effectively by PCPs based on preliminary teledermatology recommendations, preventing likely “no-shows” from taking up valuable appointment slots. The internal teledermatology system allows for capture of acute conditions and earlier treatment of chronic disease. Compared with the traditional referral system, SAF teledermatology prevented additional PCP visits related to the dermatological complaint that occurred while patients were waiting to be seen in the dermatology clinic. The lack of statistical significance in this finding is likely due to a lack of power. Nonetheless, this finding suggests that the teledermatology system is capturing chronic skin disease that would otherwise be managed ineffectively by PCPs, thus, saving the hospital system money and resources.

Ensuring that PCPs effectively adhere to teledermatology is critical. A recent study demonstrated the importance of effective participation of PCPs in a teledermatology system, with a significant portion not implementing recommendations. Despite having no prior experience with SAF teledermatology, the PCPs involved in our study had a high rate of following treatment recommendations (93%). The ease of placing an e-prescription and other orders within the Epic system at the time of the teledermatology consult review by the PCP possibly contributed to this rate.

Limitations

Our study is limited by the lack of long-term clinical outcome documentation and the small sample size. The sample size was mainly due to implementation of teledermatology in 1 outpatient medicine site and not all PCPs being trained or using the teledermatology option. As we expand teledermatology services to other outpatient clinics in PHHS, the number of consults will increase and create new challenges to continue delivering the level of care demonstrated in this pilot study. Future studies looking at long-term expansion of the program are planned.

Conclusions

This study demonstrates the effectiveness of SAF teledermatology built into Epic, the existing EHR in a large safety-net public hospital and health system through faster access to evaluation and treatment by a dermatologist. We also showed high fidelity of management and treatment recommendations made by teledermatology and carried out by PCPs. Epic-based SAF teledermatology has the potential to reduce the burden on safety-net hospital dermatology clinics by effectively managing appropriate cases remotely. In addition, SAF teledermatology integrated within the EHR allows for easier monitoring of clinical outcomes and implementation of recommendations by referring clinicians. Because Epic is currently one of the most commonly used EHRs, there is potential to expand access to SAF teledermatology at a national level.

References

- 1.Medscape. Medscape EHR report 2016. http://www.medscape.com/features/slideshow/public/ehr2016. Accessed October 1, 2016.

- 2.Warshaw EM, Lederle FA, Grill JP, et al. Accuracy of teledermatology for pigmented neoplasms. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;61(5):753-765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nelson CA, Wanat KA, Roth RR, James WD, Kovarik CL, Takeshita J. Teledermatology as pedagogy: diagnostic and management concordance between resident and attending dermatologists. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;72(3):555-557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nelson CA, Takeshita J, Wanat KA, et al. Impact of store-and-forward (SAF) teledermatology on outpatient dermatologic care: a prospective study in an underserved urban primary care setting. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74(3):484-90.e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen TS, Goldyne ME, Mathes EF, Frieden IJ, Gilliam AE. Pediatric teledermatology: observations based on 429 consults. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;62(1):61-66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Warshaw EM, Hillman YJ, Greer NL, et al. Teledermatology for diagnosis and management of skin conditions: a systematic review. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;64(4):759-772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.American Academy of Dermatology Teledermatology Toolkit. https://www.aad.org/practicecenter/managing-a-practice/teledermatology. Accessed October 1, 2016.

- 8.Martin I, Aphivantrakul PP, Chen KH, Chen SC. Adherence to teledermatology recommendations by primary health care professionals: strategies for improving follow-up on teledermatology recommendations. JAMA Dermatol. 2015;151(10):1130-1132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]