Key Points

Question

What caused unusual pruritic dermatitis after an occupational exposure in employees of a company that produced herbal medicines?

Findings

In this case series of 18 employees we hypothesized the causative agent to be Pyemotes ventricosus and an examination of the herbal specimens for ectoparasites confirmed the diagnosis. We found that changing the time when the herbs were weighed and abandoning gas fumigation containing methyl bromide led to a recurrence of an almost forgotten disease.

Meaning

This case series demonstrates the importance of examining environmental specimens for ectoparasites in cases of unexplained dermatoses.

This case series examines 18 employees of a company that produced herbal medicines who experienced unusual pruritic dermatitis.

Abstract

Importance

Although Pyemotes species have been known to cause dermatitis, recent reports are rare. During the past 30 years, only 3 outbreaks of dermatitis caused by Pyemotes ventricosus have been reported.

Objective

To analyze the causative agent of skin changes in employees of a company that produced herbal medicines.

Design, Setting, and Participants

This case series includes 18 patients (8 men, 10 women; mean age, 44 years) who contracted unusual dermatitis after an occupational exposure in July and August of 2012 while working for a company that produced herbal medicines. The patients were examined at the Lower Silesia Regional Centre of Occupational Medicine in Wroclaw, Poland.

Exposures

Workers weighed and packed 1 part of the Helichrysum arenarium herb.

Main Outcomes and Measures

We hypothesized the causative agent to be P ventricosus. An examination of the herbal specimens for ectoparasites confirmed the diagnosis.

Results

Initially 16 employees developed pruritic skin changes. Skin lesions with pruritic vesicles on an erythematous base with surrounding swelling and edema were observed. Several employees also developed a flulike illness. After 44 days, 2 new employees presented with the same skin changes. The analysis of working conditions showed that the same part of the H arenarium herb was weighed and packed at that time.

Conclusions and Relevance

We found that changing the time when the herbs were weighed and abandoning gas fumigation containing methyl bromide resulted in the recurrence of an almost forgotten disease.

Introduction

Several outbreaks of occupational dermatitis caused by Pyemotes ventricosus have been observed in the 19th and 20th centuries. In 1981 Betz et al described an outbreak of occupational dermatitis associated with straw itch mites. Since then, to our knowledge, only 3 outbreaks of dermatitis caused by P ventricosus have been reported.

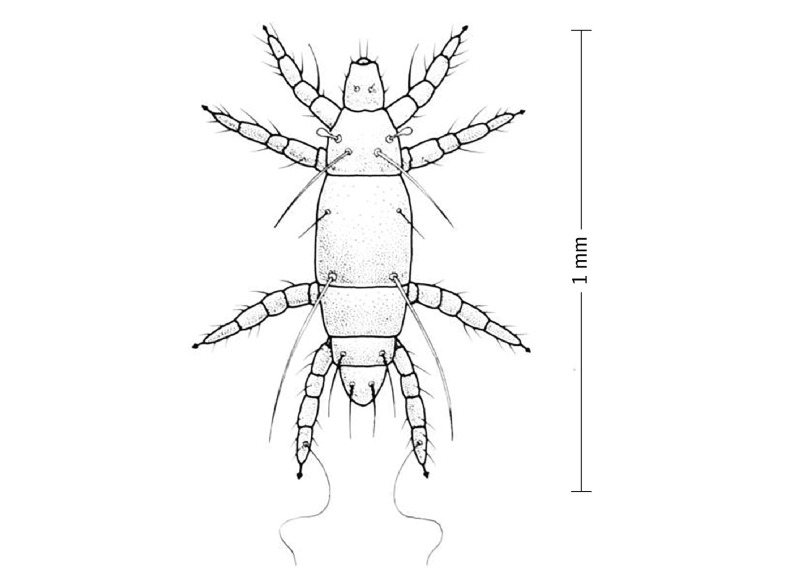

Pyemotes ventricosus, one of the pyemotid mites, which can temporally infest humans as incidental hosts, was first described by Newport in 1853 (Figure 1). These mites, also known as grain itch mite, hay itch mite, or straw itch mite, can cause a pruritic dermatitis.

Figure 1. Pyemotes ventricosus.

The mite feeds on the larva of other pests. In the absence of other pests, these mites will attach themselves to humans. From the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (https://phil.cdc.gov/phil/details.asp?pid=5492).

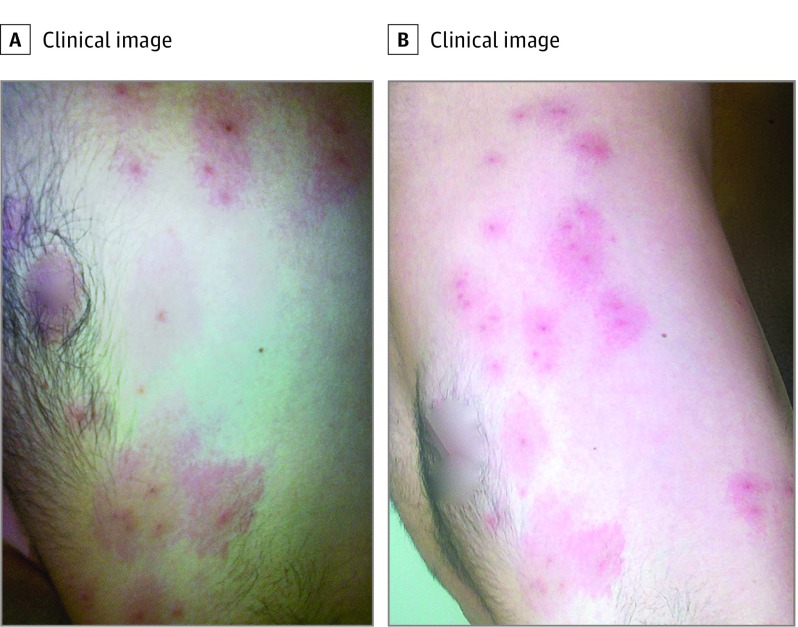

Numerous patches of intensely pruritic dermatitis appeared on the trunk and proximal extremities. Vesicular urticarial lesions on an erythematous base may present 24 hours after contact with P ventricosus. This eruption is self-limited and typically resolves in 1 to 3 weeks. Patients may also develop systemic symptoms, such as fever, chills, vomiting, or intense headache.

The diagnosis can be challenging to make because the mites are not visible to the naked eye and its bites are painless. There is also a delay of several hours between the bite and the appearance of the pruritic skin changes. Therefore, the patient does not correlate the dermatitis with the insect bites and the diagnosis has to be made based on the patient’s history and identification of the mites.

In this report, we present a case series of 18 patients with pyemotid-induced dermatitis after an occupational exposure.

Report of Cases

In August 2012, the Regional Centre of Occupational Medicine was asked to help clarify the cause of skin lesions appearing in employees of a company that produced herbal medicines.

In July 2012, 16 employees developed pruritic skin changes. Initially, 7 employees noticed skin changes presenting on the trunk (7/7), hands (4/7), neck (3/7) and, in individual cases, on the groin, face, and ears. Over the next 4 days, 9 other employees developed similar symptoms. Several employees also developed a flulike illness. None attributed the symptoms to an occupational exposure, and patients visited physicians from various specialties looking for a diagnosis.

General practitioners, internists, dermatologists, and emergency medicine specialists described the skin lesions as extremely pruritic vesicles on an erythematous base with surrounding swelling and edema. A central, darker lesion was often present (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Pruritic Changes in 1 of 18 Employees.

Skin lesions on an erythematous base with surrounding swelling and edema.

Owing to the nonspecific clinical picture, patients were given various diagnoses. Some were treated as an allergic dermatitis with oral antihistamines. Those who were suspected of having an inflammatory etiology were treated with topical steroids. Some were treated with antibiotics. Most of the changes disappeared within 2 weeks of exposure for 11 of 16 patients.

Because multiple workers noticed the same changes over a short period of time, a search for a causative factor was undertaken. Contact and allergic triggers were first suspected. However, the employer denied the introduction of any new substances, materials, or allergens, and stressed that all employees were wearing protective equipment. It was puzzling that the symptoms were occurring in different anatomical locations. An infectious agent was also suspected, but the symptoms did not appear to be contagious because they were not transmitted to family members.

After 44 days, 2 new employees presented with the same skin changes. Based on the medical history, physical examination, and photographic evidence collected, it was thought that the skin changes may be from bites. An initial diagnosis of toxic allergic dermatitis from contact with P ventricosus was established.

The working conditions at the herbal medicines company were evaluated between July 6 and July 10 and on August 23, 2012. Analysis showed that the same part of the Helichrysum arenarium herb was weighed and packed at that time. The intensity of symptoms reported by the workers depended on their role, position during handling, and time of exposure. Of note, not all employees who developed symptoms actually had direct contact with the herb. Symptoms also presented in workers who only had airborne exposure to the mite. This unusual pattern helped direct the team to the correct diagnosis.

To confirm the proposed etiology, 2 samples of inflorescence H arenarium were obtained and sent to the laboratory. Living samples of Liposcelis bostrychophilus, Acaridae (Tyrophagus putrescentiae, Carpoglyphus lactis), and also P ventricosus were isolated. Experts at the laboratory suggested that the most likely cause of the skin lesions in workers exposed to the herbs was P ventricosus. This confirmed the diagnosis and the implementation of fumigation with phosphine gas was recommended.

Discussion

This article describes a case series of 18 occupational-related cases of unusual dermatitis caused by P ventricosus. The diagnosis initially raised many doubts, both for physicians and for the management of the company. Medical examinations were carried out up to 2 months after the changes occurred. The documentation of various symptoms was taken from an interview with patients and physicians conducting the early research.

After the diagnosis was made, it was necessary to explain why these symptoms had never presented before. Helichrysum arenarium had been used at this workplace for decades. Many of the employees who presented with the skin changes weighed and were in contact with this herb in previous years and never experienced any symptoms. The crucial change that led to the development of symptoms was the season during which the herbs were sorted. In previous years, sorting of H arenarium was done in the winter months, whereas in 2012, sorting was done in July.

Principato examined the spread of the P ventricosus and found that the mite has a characteristic cycle of occurrence in the natural environment. Higher population density of the mite is seen between May and August, and it is virtually undetectable between September and November. In 2012, the sorting of the herb happened in July, when the population of the P ventricosus was highest.

The presence of P ventricosus and Acaridae indicates that the material was stored in humid conditions. Isolated pests (T putrescentiae, C lactis) can cause skin allergic reaction, but usually the course of the disease is milder. The most dangerous for humans is P ventricosus, which can cause severe pruritic skin reactions and general symptoms (as described in this case series). However, we cannot be 100% sure that the clinical picture is produced by P ventricosus because the parasitic analysis also showed the presence of other mites.

To our knowledge, there have been almost no reports of occupational-related pyemotid dermatitis published in the past 30 years. This could be largely related to an effective pest control process using methyl bromide as a gas fumigant. Methyl bromide was first registered in the United States in 1961 to control insects as a space fumigant, and has a rapid onset of action and broad spectrum of activity. It has been used as an acaricide, fungicide, herbicide, insecticide, nematicide, and rodenticide.

However, the chemical was banned because it was found to deplete ozone levels in the atmosphere. It is very likely that removing methyl bromide from the process of pest control will lead to the reemergence of cases or even outbreaks of largely forgotten diseases, such as the one described in this case.

Conclusions

The combination of abandoning gas fumigation with methyl bromide and changing the time of weighing herbs led to an outbreak of a pruritic skin lesions among 18 employees of a medical herb company. This resulted in the reemergence of an almost forgotten disease. Our case series demonstrates the importance of examining environmental specimens for ectoparasites in cases of unexplained dermatoses.

References

- 1.Betz TG, Davis BL, Fournier PV, Rawlings JA, Elliot LB, Baggett DA. Occupational dermatitis associated with straw itch mites (Pyemotes ventricosus). JAMA. 1982;247(20):2821-2823. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Czarnecki N, Kraus H. [Occupational dermatitis caused by Pyemotes ventricosus]. Z Hautkr. 1976;51(13):527-532. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Del Giudice P, Blanc-Amrane V, Bahadoran P, et al. . Pyemotes ventricosus dermatitis, southeastern France. Emerg Infect Dis. 2008;14(11):1759-1761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Taddei L, Principato M, Buttarini L, Quercia A. Dermatite occupazionale epidemica da Pyemotes ventricosus (Acari Pyemotidae). [Article in Italian]. Annali Italiani di Dermatologia Allergologica. 2005;59:36-38. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Grob M, Dorn K, Lautenschlager S. [Grain mites. A small epidemic caused by Pyemotes species]. Hautarzt. 1998;49(11):838-843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McClain D, Dana AN, Goldenberg G. Mite infestations. Dermatol Ther. 2009;22(4):327-346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Newport G. Further observations on the habits of monodontomerus; with some account of a new acarus (Heteropus ventricosus), a parasite in the nests of Anthophora retusa. Transactions of the Linnean Society of London. 1953;21:95-102. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fine RM, Scott HG. Straw itch mite dermatitis caused by pyemotes ventricosus: comparative aspects. South Med J. 1965;58:416-420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Micks DW. An outbreak of dermatitis due to the grain itch mite, Pyemotes ventricosus Newport. Tex Rep Biol Med. 1962;20:221-226. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Corazza M, Tassinari M, Pezzi M, et al. . Multidisciplinary approach to Pyemotes ventricosus papular urticaria dermatitis. Acta Derm Venereol. 2014;94(2):248-249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Principato M. Observations on the spread of Pyemotes ventricosus (Prostigmata: Pyemotidae) in houses in Umbria, Central Italy. Acarid Phylogeny and Evolution: Adaptation in Mites and Ticks 2002. Springer International Publishing. Dordrecht, Netherlands. [Google Scholar]

- 12.National Pecticide Information center Methyl Bromide (General Fact Sheet). http://npic.orst.edu/factsheets/MBgen.pdf. Accessed March 31, 2015.

- 13.Fields PG, White ND. Alternatives to methyl bromide treatments for stored-product and quarantine insects. Annu Rev Entomol. 2002;47:331-359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]