Key Points

Question

Is the rate of hypoglycemia lower with insulin degludec vs insulin glargine U100 in insulin-treated patients with type 2 diabetes?

Findings

In this randomized crossover clinical trial of 721 patients, insulin degludec resulted in a significantly lower rate of overall symptomatic hypoglycemic episodes over a 16-week maintenance period compared with insulin glargine U100 (186 vs 265 episodes per 100 patient-years of exposure, respectively).

Meaning

Patients with type 2 diabetes treated with insulin degludec compared with insulin glargine U100 had a reduced risk of overall symptomatic hypoglycemia.

This randomized crossover clinical trial compares the effects of insulin degludec vs insulin glargine U100 on rates of hypoglycemia in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM).

Abstract

Importance

Hypoglycemia, a serious risk for insulin-treated patients with type 2 diabetes, negatively affects glycemic control.

Objective

To test whether treatment with basal insulin degludec is associated with a lower rate of hypoglycemia compared with insulin glargine U100 in patients with type 2 diabetes.

Design, Setting, and Participants

Randomized, double-blind, treat-to-target crossover trial including two 32-week treatment periods, each with a 16-week titration period and a 16-week maintenance period. The trial was conducted at 152 US centers between January 2014 and December 2015 in 721 adults with type 2 diabetes and at least 1 hypoglycemia risk factor who were previously treated with basal insulin with or without oral antidiabetic drugs.

Interventions

Patients were randomized 1:1 to receive once-daily insulin degludec followed by insulin glargine U100 (n = 361) or to receive insulin glargine U100 followed by insulin degludec (n = 360) and randomized 1:1 to morning or evening dosing within each treatment sequence.

Main Outcomes and Measures

The primary end point was the rate of overall symptomatic hypoglycemic episodes (severe or blood glucose confirmed [<56 mg/dL]) during the maintenance period. Secondary end points were the rate of nocturnal symptomatic hypoglycemic episodes (severe or blood glucose confirmed, occurring between 12:01 am and 5:59 am) and the proportion of patients with severe hypoglycemia during the maintenance period.

Results

Of the 721 patients randomized (mean [SD] age, 61.4 [10.5] years; 53.1% male), 580 (80.4%) completed the trial. During the maintenance period, the rates of overall symptomatic hypoglycemia for insulin degludec vs insulin glargine U100 were 185.6 vs 265.4 episodes per 100 patient-years of exposure (PYE) (rate ratio = 0.70 [95% CI, 0.61-0.80]; P < .001; difference, −23.66 episodes/100 PYE [95% CI, −33.98 to −13.33]), and the proportions of patients with hypoglycemic episodes were 22.5% vs 31.6% (difference, −9.1% [95% CI, −13.1% to −5.0%]). The rates of nocturnal symptomatic hypoglycemia with insulin degludec vs insulin glargine U100 were 55.2 vs 93.6 episodes/100 PYE (rate ratio = 0.58 [95% CI, 0.46-0.74]; P < .001; difference, −7.41 episodes/100 PYE [95% CI, −11.98 to −2.85]), and the proportions of patients with hypoglycemic episodes were 9.7% vs 14.7% (difference, −5.1% [95% CI, −8.1% to −2.0%]). The proportions of patients experiencing severe hypoglycemia during the maintenance period were 1.6% (95% CI, 0.6%-2.7%) for insulin degludec vs 2.4% (95% CI, 1.1%-3.7%) for insulin glargine U100 (McNemar P = .35; risk difference, −0.8% [95% CI, −2.2% to 0.5%]). Statistically significant reductions in overall and nocturnal symptomatic hypoglycemia for insulin degludec vs insulin glargine U100 were also seen for the full treatment period.

Conclusions and Relevance

Among patients with type 2 diabetes treated with insulin and with at least 1 hypoglycemia risk factor, 32 weeks’ treatment with insulin degludec vs insulin glargine U100 resulted in a reduced rate of overall symptomatic hypoglycemia.

Trial Registration

clinicaltrials.gov Identifier: NCT02030600

Introduction

Hypoglycemia and concerns regarding hypoglycemia are acknowledged as the main limiting factors for achieving tight glycemic control. The importance of good glycemic control in reducing diabetic complications is well documented. Insulin is recognized as the most effective blood glucose–lowering therapy and is often necessary in the management of type 2 diabetes (T2D) as the disease progresses.

The insulin analogs glargine U100 and detemir have longer half-lives than neutral protamine Hagedorn (NPH) insulin and, at similar hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) levels, reduce the frequency of overall and nocturnal hypoglycemia in T2D by 42% to 65% and 44% to 53%, respectively, compared with NPH insulin. This may be due to lower day-to-day variability vs NPH insulin. With insulin degludec, the day-to-day variability has been shown to be lower than that of insulin glargine U100 and U300.

The insulin degludec phase 3a program included 5 open-label trials in patients with T2D comparing insulin degludec with insulin glargine U100. A prespecified meta-analysis of these trials showed that at similar HbA1c levels, the rates of overall and nocturnal confirmed hypoglycemia were 17% and 32% lower, respectively, with insulin degludec than with insulin glargine U100. The SWITCH 2 trial was designed to test this hypoglycemia benefit with insulin degludec, using a double-blind, crossover trial design among basal insulin–treated patients with T2D who had at least 1 risk factor for hypoglycemia.

Methods

Trial Design and Participants

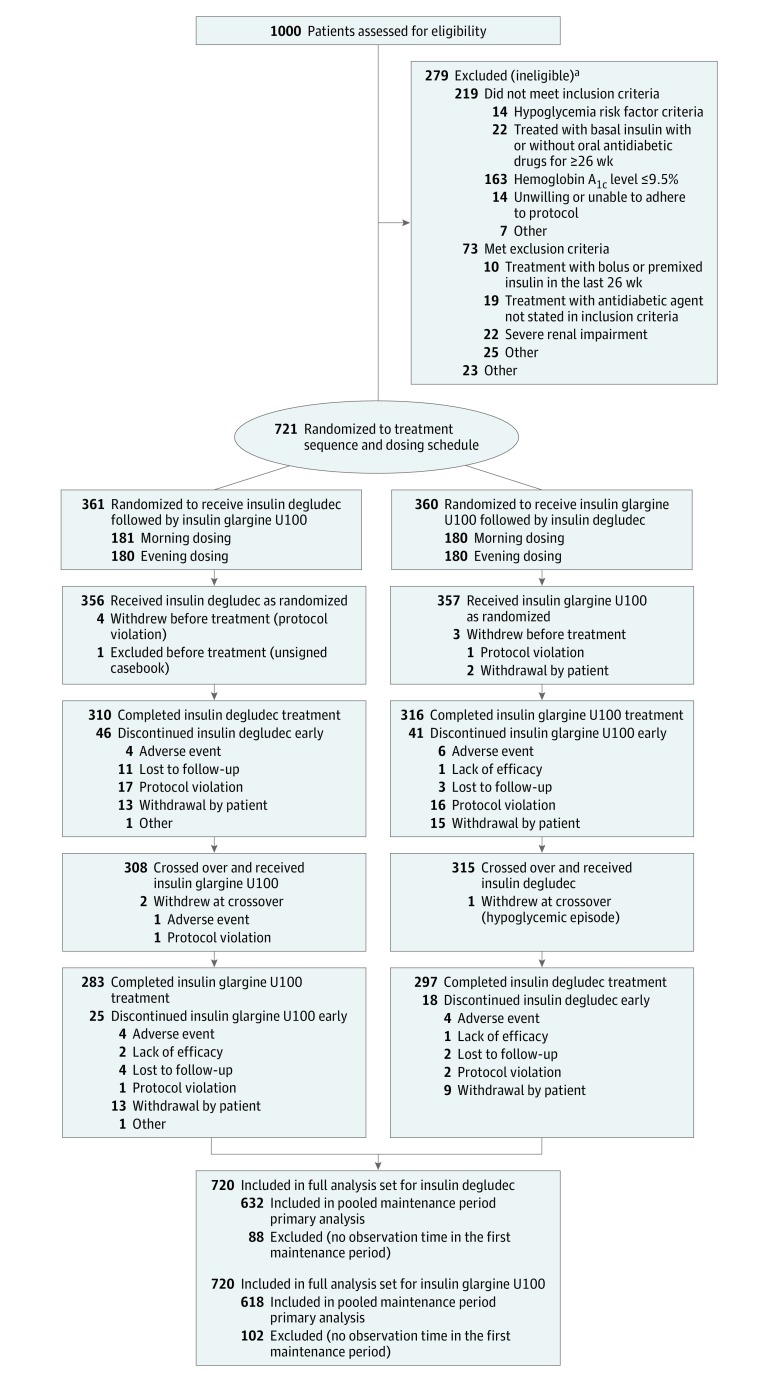

The trial was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and International Conference of Harmonisation Good Clinical Practice. Before trial initiation, the protocol, consent form, and patient information sheet were reviewed and approved by appropriate health authorities and an independent ethics committee or institutional review board at each site. Written informed consent was obtained from all participating patients. This randomized, double-blind, 2-period crossover, multicenter, treat-to-target trial was conducted in patients with T2D treated with basal insulin with or without oral antidiabetic drugs (OADs) (Figure 1 and eFigure 1 in Supplement 1), across 152 sites in the United States between January 2014 and December 2015. The total trial duration was 65 weeks; this included 32 weeks’ treatment with once-daily insulin degludec or insulin glargine U100 followed by crossover to insulin glargine U100 or insulin degludec, respectively, for a further 32 weeks, plus 1 week of follow-up (eFigure 1 in Supplement 1). Each 32-week treatment period consisted of a 16-week titration period (to reduce potential carryover effects and obtain stable glycemic control) and a 16-week maintenance period (to compare the difference in hypoglycemia when glycemic control and dose were stable).

Figure 1. Patient Flow Through the SWITCH 2 Randomized Clinical Trial.

aSome patients fulfilled more than 1 inclusion or exclusion criterion.

The inclusion criteria specified adults (aged ≥18 years) diagnosed with T2D for at least 26 weeks, an HbA1c level of 9.5% or lower (to convert to proportion of total hemoglobin, multiply by 0.01), body mass index (calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared) of 45 or lower, and treatment with any basal insulin with or without OADs (any combination of metformin, dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitor, α-glucosidase inhibitor, thiazolidinediones, and sodium glucose cotransporter-2 inhibitor) for at least 26 weeks. To include a broader population of patients with T2D treated with basal insulin (compared with the phase 3a trials, which excluded patients with recurrent severe hypoglycemia or hypoglycemia unawareness) better resembling that encountered in clinical practice, patients had to fulfill at least 1 of the following risk criteria for developing hypoglycemia: (1) experienced at least 1 severe hypoglycemic episode within the last year (based on the American Diabetes Association definition); (2) moderate chronic renal failure (estimated glomerular filtration rate of 30-59 mL/min/1.73 m2); (3) hypoglycemic symptom unawareness; (4) exposure to insulin for longer than 5 years; or (5) an episode of hypoglycemia (symptoms and/or blood glucose level ≤70 mg/dL [to convert to millimoles per liter, multiply by 0.0555]) within the last 12 weeks. Patients treated with bolus or premixed insulin or with sulfonylurea or meglitinide within 26 weeks before the first visit were not included. The determination of race and ethnicity was self-reported by the participant based on fixed categories.

The trial protocol is available in Supplement 2, and the statistical analysis plan is available in Supplement 3.

Interventions

Patients were randomized using a trial-specific, interactive-voice, web-response system using a simple sequential allocation from a blocked randomization schedule without stratifying factors. Patients were randomized 1:1 to one of the treatment sequences (insulin degludec followed by insulin glargine U100 or insulin glargine U100 followed by insulin degludec) in a blinded manner. Within each treatment sequence, patients were randomized 1:1 to administer once-daily basal insulin in either the morning (from waking to breakfast) or the evening (from main evening meal to bedtime). Assigned administration timing was maintained throughout the trial.

The trial was double blinded, and all involved parties were blinded to insulin degludec and insulin glargine U100 treatment sequence allocation throughout the trial. To maintain blinding, insulin degludec 100 U/mL (Novo Nordisk) and insulin glargine 100 U/mL (Sanofi) were both administered subcutaneously using identical vials via syringe. If switching from once-daily dosing, the starting dose for both treatments was the pretrial dose; if switching from twice-daily dosing, the pretrial dose was reduced by 20% at the investigator’s discretion. The starting dose for treatment period 2 was the dose from the end of treatment period 1.

Patients were supplied with a blood glucose monitor and instructed to measure their blood glucose level before breakfast on the 3 days before a visit or telephone contact (weekly) and also whenever a hypoglycemic episode was suspected. The insulin dose was titrated once weekly based on the mean of 3 prebreakfast self-measured blood glucose measurements, to a fasting blood glucose target of 71 to 90 mg/dL. The insulin dose was adjusted in multiples of 2 U by –4 U to +8 U depending on prebreakfast self-measured blood glucose level (eTable 1 in Supplement 1). All pretrial OADs were continued at the pretrial dose throughout the trial.

End Points

The primary end point was the rate of overall symptomatic hypoglycemic episodes (severe [an episode requiring third-party assistance, externally adjudicated] or blood glucose confirmed [<56 mg/dL]) during the maintenance period (weeks 16-32 and 48-64). The secondary end points were the rate of nocturnal symptomatic hypoglycemic episodes (severe or blood glucose confirmed, occurring between 12:01 AM and 5:59 AM [both inclusive]) and the proportion of patients experiencing 1 or more severe hypoglycemic episodes, both in the maintenance period. Other hypoglycemic end points included the rates of overall symptomatic, nocturnal symptomatic, and severe hypoglycemia for the full treatment period, the rate of severe hypoglycemia, and the proportion of patients experiencing 1 or more overall or nocturnal symptomatic episodes in the maintenance period and the full treatment period. The hypoglycemia definition is illustrated in eFigure 2 in Supplement 1. All severe episodes reported by investigators or identified via a predefined Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities version 18.1 search of safety data were adjudicated prospectively by an external committee; only those confirmed by adjudication were included in the analysis (eTable 2 in Supplement 1).

Efficacy end points measured were change in HbA1c level, fasting plasma glucose level, and prebreakfast self-measured blood glucose level after 32 weeks of treatment. Other safety end points included daily insulin dose, change from baseline in body weight after 32 weeks, incidence of adverse events, vital signs (including blood pressure and pulse), ophthalmoscopy, electrocardiography, and standard biochemical parameters.

Statistical Analysis

Analyses of all end points were based on the full analysis set (all randomized patients) following the intention-to-treat principle. Efficacy end points were summarized for the full analysis set; safety end points were summarized for the safety analysis set (patients receiving ≥1 dose of investigational product or comparator). Full details of the statistical analysis plan are in Supplement 3. All analyses were conducted using SAS version 9.4 statistical software (SAS Institute Inc).

Statistical superiority testing of the primary and secondary end points was performed following a hierarchical testing procedure (eFigure 3 in Supplement 1) to control the type I error rate in the strong sense (ie, the error rate was controlled whether or not the global null hypothesis was true). Noninferiority in HbA1c level was a prerequisite for both treatment periods before testing the primary end point. The primary and secondary analyses were prespecified to be tested using a 1-sided test on a 2.5% level. Other analyses used 2-sided tests at a 5% level.

The trial was powered to evaluate superiority of the primary end point. Based on the assumption that up to 10% of the randomized patients may not contribute to the analysis, 600 patients needed to contribute to the analysis if 668 patients were randomized, to ensure 88.9% power to demonstrate a 38% benefit (ie, a rate ratio of 0.62), with an expected rate of overall symptomatic hypoglycemia of 0.5 episodes per patient-year of exposure (PYE).

A Poisson model with patients as random effect; treatment, period, sequence, and dosing time as fixed effects; and logarithm of the observation time (100 years) as offset was prespecified as the primary analysis to estimate the rate ratio of overall symptomatic hypoglycemia during the maintenance period. Only patients with positive observation time during the first maintenance period contributed to the estimated treatment ratio. Statistical superiority was considered confirmed if the upper bound of the 2-sided 95% CI for the estimated rate ratio (ERR) was less than 1. Sensitivity analyses were performed to test the robustness of the results for the primary end point and for the secondary end point nocturnal symptomatic hypoglycemia, using a Poisson model on the subset of patients exposed in both maintenance periods, using a Poisson model on completers only, and using a negative binomial model.

Missing data were explored to ascertain whether the patients who dropped out before the first maintenance period differed from those exposed during the first maintenance period, as these patients did not contribute to the primary analysis, and whether there were any differences between the 2 treatments in patients who dropped out. The effects of missing data on the primary analysis were investigated with a post hoc tipping-point analysis. Missing data were imputed assuming that the rate of hypoglycemia for a noncompleter was similar to that for a patient completing the same treatment period who had a similar number of episodes before the time of withdrawal. The imputed number of episodes for a patient withdrawing while receiving insulin degludec was gradually increased until the treatment contrast between the 2 insulins was no longer significant. A post hoc analysis of the absolute difference in hypoglycemia rate was conducted using a nonlinear Poisson model with a specified mean parameter, measuring the difference between average nonexisting patients receiving insulin degludec and insulin glargine U100, respectively (50% treatment period 1; 50% evening dose; 50% treatment sequence of insulin degludec followed by insulin glargine U100).

McNemar nonparametric test was prespecified to compare the proportion of patients experiencing severe hypoglycemia with the 2 treatments. To quantify the differences in proportions with 95% CI post hoc, a binomial distribution with correlated measurements was assumed.

Change from baseline in HbA1c level after 32 weeks of treatment was analyzed separately for each treatment period, using a mixed model for repeated measurements with an unstructured covariance matrix, including treatment period, visit, sex, antidiabetic therapy at screening, and dosing time (morning vs evening) as fixed effects and age and baseline HbA1c level as covariates. All fixed factors and covariates are nested within visit. For the first treatment period, the analysis was conducted using data from all patients with observation time in the first maintenance period. For the second treatment period, the analysis was repeated and all patients with an HbA1c measurement after crossover contributed to the analysis. Noninferiority for HbA1c level was confirmed if the upper bound of the 1-sided 95% CI for the difference in mean change was 0.4% or less.

A post hoc analysis of insulin dose was conducted for patients with observation time in maintenance period 1, using a log-linear mixed model for repeated measurements with treatment, period, dosing time (morning or evening), and visit as fixed effects, patient as random effect, and the log-transformed baseline dose as a covariate.

Results

Of 1000 patients screened, 721 (mean age, 61.4 [10.5] years; 53.1% male) were randomized to trial product (50.1% to morning dosing and 49.9% to evening dosing) and 713 were exposed to trial product (Figure 1). Overall, 580 patients (80.4%) completed the trial. The proportion of patients withdrawing and the reasons for withdrawal were similar for both treatment sequences (Figure 1). The most common reasons for withdrawal were withdrawal by patient and protocol violation (eg, not meeting the inclusion criteria, meeting the exclusion criteria, noncompliance, or participation in other trials). Patients discontinuing prior to the first maintenance period were similar to patients with observation time in the first maintenance period.

The full analysis set comprised 720 patients; 1 patient was excluded because of an unsigned casebook. Baseline characteristics, insulin treatment at screening, and pretrial regimen are summarized in Table 1. At screening, 59 patients (8.2%) were using NPH insulin, 159 (22.1%) insulin detemir, and 502 (69.7%) insulin glargine U100, with 606 (84.2%) administering basal insulin once daily and 114 (15.8%) twice daily. Overall, 570 patients (79.1%) were receiving 1 or more OADs (Table 1), with the majority of patients (66.9%) treated with basal insulin plus metformin at screening.

Table 1. Baseline Characteristics.

| Characteristic | No. (%) of Patients | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Insulin Degludec Followed by Insulin Glargine U100 | Insulin Glargine U100 Followed by Insulin Degludec | All Patients | Completers | |

| Full analysis set | 360 | 360 | 720 | 580 |

| Men | 191 (53.1) | 191 (53.1) | 382 (53.1) | 310 (53.4) |

| Race | ||||

| White | 292 (81.1) | 286 (79.4) | 578 (80.3) | 469 (80.9) |

| Black | 54 (15.0) | 52 (14.4) | 106 (14.7) | 83 (14.3) |

| Asian | 6 (1.7) | 16 (4.4) | 22 (3.1) | 17 (2.9) |

| Other | 8 (2.2) | 6 (1.7) | 14 (1.9) | 11 (1.9) |

| Hispanic or Latino | 140 (38.9) | 122 (33.9) | 262 (36.4) | 210 (36.2) |

| Age, mean (SD), y | 61.5 (10.7) | 61.2 (10.3) | 61.4 (10.5) | 61.6 (10.4) |

| Body weight, mean (SD), kg | 90.8 (19.4) | 92.6 (19.5) | 91.7 (19.5) | 92.1 (19.7) |

| BMI, mean (SD) | 32.0 (5.6) | 32.3 (5.7) | 32.2 (5.6) | 32.3 (5.7) |

| Duration of diabetes, mean (SD), y | 14.2 (8.3) | 13.9 (8.0) | 14.1 (8.1) | 14.0 (8.1) |

| HbA1c, mean (SD), % | 7.6 (1.1) | 7.6 (1.1) | 7.6 (1.1) | 7.5 (1.1) |

| Fasting plasma glucose, mean (SD), mg/dL | 139.2 (53.5) | 134.9 (51.6) | 137.0 (52.6) | 135.7 (50.9) |

| eGFR, mean (SD), mL/min/1.73 m2 | 78.8 (21.4) | 77.7 (21.3) | 78.3 (21.3) | 78.3 (21.0) |

| Smoking status | ||||

| Never | 182 (50.6) | 182 (50.6) | 364 (50.6) | 302 (52.1) |

| Previous | 127 (35.3) | 118 (32.8) | 245 (34.0) | 184 (31.7) |

| Current | 51 (14.2) | 60 (16.7) | 111 (15.4) | 94 (16.2) |

| Pretrial basal insulin treatment | ||||

| NPH insulin | 30 (8.3) | 29 (8.1) | 59 (8.2) | 48 (8.3) |

| Insulin detemir | 67 (18.6) | 92 (25.6) | 159 (22.1) | 129 (22.2) |

| Insulin glargine U100 | 263 (73.1) | 239 (66.4) | 502 (69.7) | 403 (69.5) |

| Pretrial treatment regimen | ||||

| Basal once daily | 311 (86.4) | 295 (81.9) | 606 (84.2) | 488 (84.1) |

| Basal twice daily | 49 (13.6) | 65 (18.1) | 114 (15.8) | 92 (15.9) |

| OADs at screening | ||||

| 0 | 69 (19.2) | 81 (22.5) | 150 (20.8) | 120 (20.7) |

| 1 | 234 (65.0) | 214 (59.4) | 448 (62.2) | 366 (63.1) |

| ≥2 | 57 (15.8) | 65 (18.1) | 122 (16.9) | 94 (16.2) |

| Patients with hypoglycemia risk inclusion criterion | ||||

| Fulfilling ≥1 of following 4 criteria | 265 (73.6) | 281 (78.1) | 546 (75.8) | 438 (75.5) |

| ≥1 Severe hypoglycemic episode in last y | 61 (16.9) | 57 (15.8) | 118 (16.4) | 94 (16.2) |

| Moderate chronic renal failure | 74 (20.6) | 85 (23.6) | 159 (22.1) | 128 (22.1) |

| Hypoglycemia unawareness | 62 (17.2) | 67 (18.6) | 129 (17.6) | 109 (18.8) |

| Exposed to insulin for ≥5 y | 173 (48.1) | 183 (50.8) | 356 (49.4) | 295 (50.9) |

| Hypoglycemic episode within last 12 wk | 243 (67.5) | 235 (65.3) | 478 (66.4) | 386 (66.6) |

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index (calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared); eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; HbA1c, hemoglobin A1c; NPH, neutral protamine Hagedorn; OADs, oral antidiabetic drugs.

SI conversion factors: To convert HbA1c to proportion of total hemoglobin, multiply by 0.01; glucose to millimoles per liter, multiply by 0.0555.

Primary End Point

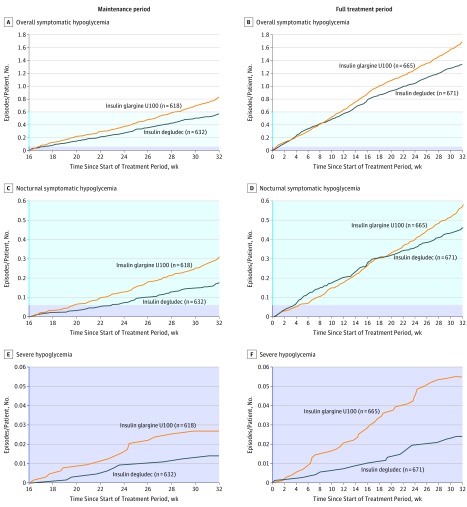

The rate of overall symptomatic hypoglycemia during the maintenance period was statistically significantly lower with insulin degludec compared with insulin glargine U100 (185.6 vs 265.4 episodes/100 PYE, respectively; ERR = 0.70 [95% CI, 0.61 to 0.80]; P < .001; rate difference, −23.66 episodes/100 PYE [95% CI, −33.98 to −13.33]) (Figure 2A and Table 2). Sensitivity analyses supported the primary analysis, confirming the lower rate of overall symptomatic hypoglycemia with insulin degludec compared with insulin glargine U100 (all P < .001) (eFigure 4 in Supplement 1). The post hoc tipping-point analysis showed that the statistically significant difference between the 2 treatments remained until each noncompleter receiving insulin degludec was assumed to experience an additional 4 hypoglycemic episodes compared with 0 episodes for noncompleters receiving insulin glargine U100. The additional 4 events for noncompleters receiving insulin degludec corresponded to an observed rate of 1640 episodes/100 PYE compared with the observed rate of 184 episodes/100 PYE for insulin degludec completers (mean number of events, 5.1 vs 0.6, respectively) (eTable 3 in Supplement 1).

Figure 2. Cumulative Rates of Hypoglycemia per Patient.

Overall symptomatic hypoglycemia in the maintenance (A) and full treatment (B) periods, nocturnal symptomatic hypoglycemia in the maintenance (C) and full treatment (D) periods, and severe hypoglycemia in the maintenance (E) and full treatment (F) periods. Data are observed mean number of hypoglycemic episodes per patient for the safety analysis set. Tinted region in blue indicates range from y = 0.06 to 0.6 mean cumulative number of episodes per person; tinted region in purple, y = 0 to 0.06 mean cumulative number of episodes per person.

Table 2. Analysis of Hypoglycemia in the Maintenance and Full Treatment Periodsa.

| Definitionb | Safety Analysis Set (n = 713) | Insulin Degludec vs Insulin Glargine U100, Full Analysis Set (n = 720) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Insulin Degludec | Insulin Glargine U100 | |||||||||

| Patients, No. (%) | Episodes, No. | Episodes, No./100 PYE | Patients, No. (%) | Episodes, No. | Episodes, No./100 PYE | ERR (95% CI) | P Value | Absolute Rate Difference in Episodes, No./100 PYE (95% CI) | Difference in % of Patients With Episodes (95% CI), % | |

| Maintenance Periodc | ||||||||||

| Included in the analysis | ||||||||||

| No. | 632 | 618 | ||||||||

| PYE | 190.2 | 186.9 | ||||||||

| Overall symptomatic hypoglycemiad,e | 142 (22.5) | 353 | 185.6 | 195 (31.6) | 496 | 265.4 | 0.70 (0.61-0.80) |

<.001 | −23.66 (−33.98 to −13.33) |

−9.1 (−13.1 to −5.0) |

| Nocturnal symptomatic hypoglycemiae | 61 (9.7) | 105 | 55.2 | 91 (14.7) | 175 | 93.6 | 0.58 (0.46-0.74) |

<.001 | −7.41 (−11.98 to −2.85) |

−5.1 (−8.1 to −2.0) |

| Severe hypoglycemiae | 10 (1.6) | 10 | 5.3 | 15 (2.4) | 17 | 9.1 | 0.54 (0.21-1.42) |

.35 | −1.18 (−2.77 to 0.41) |

−0.8 (−2.2 to 0.5) |

| Full Treatment Periodf | ||||||||||

| Included in the analysis | ||||||||||

| No. | 671 | 665 | ||||||||

| PYE | 388.8 | 383.5 | ||||||||

| Overall symptomatic hypoglycemia | 243 (36.2) | 855 | 219.9 | 277 (41.7) | 1055 | 275.1 | 0.77 (0.70-0.85) |

<.001 | −19.4 (−27.07 to −11.74) |

−5.4 (−9.6 to −1.2) |

| Nocturnal symptomatic hypoglycemia | 116 (17.3) | 280 | 72.0 | 145 (21.8) | 339 | 88.4 | 0.75 (0.64-0.89) |

<.001 | −4.4 (−7.23 to −1.58) |

−4.5 (−7.7 to −1.3) |

| Severe hypoglycemia | 15 (2.2) | 17 | 4.4 | 26 (3.9) | 36 | 9.4 | 0.49 (0.26-0.94) |

.03 | −0.62 (−1.44 to 0.21) |

−1.7 (−3.3 to −0.0) |

Abbreviations: ERR, estimated rate ratio; PYE, patient-years of exposure.

The prespecified analysis of hypoglycemia was conducted using a Poisson model with patient as a random effect; treatment, period, sequence, and dosing time as fixed effects; and logarithm of the exposure time (100 years) as offset. Statistical superiority was considered confirmed if the upper bound of the 2-sided 95% CI for the rate ratio was less than 1. A post hoc analysis of the rate difference was conducted using a nonlinear Poisson model, and a post hoc analysis comparing the proportion of patients with events was conducted using a binomial distribution assuming correlated measurements.

Overall hypoglycemia was defined as severe (requiring third-party aid, externally adjudicated) or blood glucose–confirmed (<56 mg/dL [to convert to millimoles per liter, multiply by 0.0555]) symptomatic episodes; nocturnal hypoglycemia was defined as severe or blood glucose–confirmed symptomatic episodes occurring between 12:01 am and 5:59 am (both inclusive).

Only patients who were exposed in the first maintenance period contributed to the maintenance period analysis (88 patients receiving insulin degludec and 102 patients receiving insulin glargine U100 did not contribute to the analysis because of no observation time in the first maintenance period).

Primary end point.

Tested for superiority in hierarchical testing.

Only patients who were exposed during the full treatment period contributed to the full treatment period analysis (49 patients receiving insulin degludec and 55 patients receiving insulin glargine U100 did not contribute to the analysis because of no observation time in the full treatment period).

Secondary End Points

The rate of nocturnal symptomatic hypoglycemia was also statistically significantly lower with insulin degludec vs insulin glargine U100 during the maintenance period (55.2 vs 93.6 episodes/100 PYE, respectively; ERR= 0.58 [95% CI, 0.46 to 0.74]; P < .001; rate difference, −7.41 episodes/100 PYE [95% CI, −11.98 to −2.85]) (Figure 2C and Table 2). Sensitivity analyses were consistent in showing lower rates of nocturnal symptomatic hypoglycemia with insulin degludec vs insulin glargine U100 (all P < .001) (eFigure 4 in Supplement 1).

The proportion of patients experiencing at least 1 severe hypoglycemic episode during the maintenance period was 1.6% (95% CI, 0.6% to 2.7%) for insulin degludec and 2.4% (95% CI, 1.1% to 3.7%) for insulin glargine U100 (difference, −0.8% [95% CI, −2.2% to 0.5%]) (Table 2), but this difference was not statistically significant (P = .35).

Other End Points

Hypoglycemia

For the full treatment period, there were statistically significant reductions in the rates of both overall symptomatic hypoglycemia and nocturnal symptomatic hypoglycemia with insulin degludec vs insulin glargine U100 (overall symptomatic hypoglycemia: 219.9 vs 275.1 episodes/100 PYE, respectively; ERR = 0.77 [95% CI, 0.70 to 0.85]; P < .001; rate difference, −19.4 [95% CI, −27.07 to −11.74]; nocturnal symptomatic hypoglycemia: 72.0 vs 88.4 episodes/100 PYE, respectively; ERR = 0.75 [95% CI, 0.64 to 0.89]; P < .001; rate difference, −4.4 [95% CI, −7.23 to −1.58]) (Figure 2B and D and Table 2).

The rate of severe hypoglycemia was not significantly lower with insulin degludec vs insulin glargine U100 during the maintenance period (ERR = 0.54 [95% CI, 0.21 to 1.42]; P = .35; rate difference, −1.18 [95% CI, −2.77 to 0.41]), although the rate was statistically significantly lower over the full treatment period (ERR = 0.49 [95% CI, 0.26 to 0.94]; P = .03; rate difference, −0.62 [95% CI, −1.44 to 0.21]) (Figure 2E and F and Table 2).

The proportions of patients experiencing overall symptomatic hypoglycemia and nocturnal symptomatic hypoglycemia (Table 2) were both statistically significantly lower with insulin degludec vs insulin glargine U100 in the maintenance period (overall symptomatic hypoglycemia: 22.5% [95% CI, 19.2% to 25.8%] vs 31.6% [95% CI, 27.9% to 35.3%], respectively; P < .001; difference in proportions, −9.1% [95% CI, −13.1% to −5.0%]; nocturnal symptomatic hypoglycemia: 9.7% [95% CI, 7.3% to 12.1%] vs 14.7% [95% CI, 11.8% to 17.6%], respectively; P = .001; difference in proportions, −5.1% [95% CI, −8.1% to −2.0%]). These results were consistent with the full treatment period (Table 2).

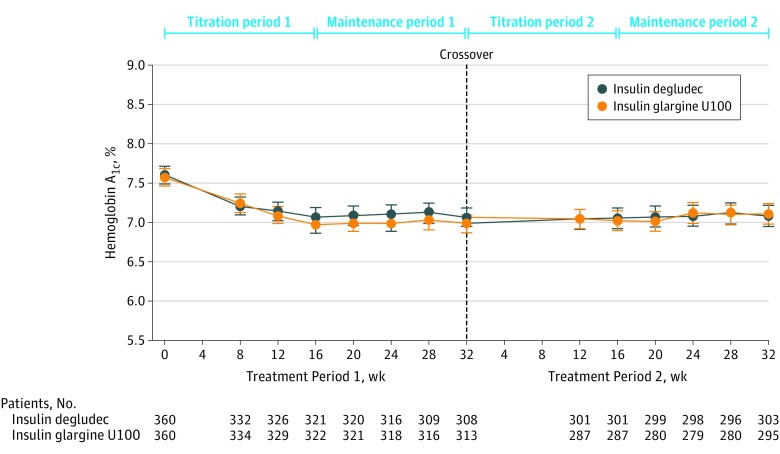

Glycemic Control

The observed mean (SD) HbA1c level at the end of treatment period 1 was 7.06% (1.07%) with insulin degludec vs 6.98% (1.03%) with insulin glargine U100 (estimated treatment difference [ETD], 0.09% [95% CI, –0.04% to 0.23%]; P < .001 for noninferiority) and at the end of treatment period 2 was 7.08% (1.23%) with insulin degludec vs 7.11% (1.15%) with insulin glargine U100 (ETD, 0.06% [95% CI, –0.07% to 0.18%]; P < .001 for noninferiority) (Figure 3). Noninferiority of insulin degludec compared with insulin glargine U100 for HbA1c levels was confirmed for both treatment periods (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Hemoglobin A1c Level Over Time.

Data are observed mean level of hemoglobin A1c for the full analysis set. Error bars indicate 95% confidence intervals. See eFigure 1 in Supplement 1 for the design of the treatment periods.

At the end of treatment period 1, the observed mean (SD) fasting plasma glucose level decreased in the group treated with insulin degludec followed by insulin glargine U100 from 139.2 (53.5) mg/dL at baseline to 107.3 (41.7) mg/dL, with a slight increase when switched to insulin glargine U100 in treatment period 2 (mean [SD], 114.1 [51.9] mg/dL). A decrease in the mean (SD) fasting plasma glucose level was also observed in treatment period 1 of the group treated with insulin glargine U100 followed by insulin degludec, from 134.9 (51.6) mg/dL at baseline to 107.0 (39.8) mg/dL, which was maintained when switched to insulin degludec in treatment period 2 (mean [SD], 107.6 [51.3] mg/dL) (eFigure 5A in Supplement 1). The mean prebreakfast self-measured blood glucose level (used for dose adjustment) decreased during the first 16 weeks of the trial in both study treatment groups and then remained stable for the duration of the trial (eFigure 5B in Supplement 1).

Insulin Dose and Body Weight

At the end of treatment period 1, the observed mean (SD) dose increased in the group treated with insulin degludec followed by insulin glargine U100 from 40 (22) U at baseline to 70 (41) U, with a further increase when switched to insulin glargine U100 in treatment period 2 (mean [SD], 83 [50] U). An increase in dose was also observed in treatment period 1 of the group treated with insulin glargine U100 followed by insulin degludec, from 43 (26) U at baseline to 74 (41) U, with a further increase when switched to insulin degludec in treatment period 2 (mean [SD], 83 [54] U) (eTable 4 in Supplement 1). A post hoc analysis showed that after 32 weeks of treatment, the insulin dose was significantly lower with insulin degludec vs insulin glargine U100 (estimated treatment ratio = 0.96 [95% CI, 0.94 to 0.98]; P < .001).

Mean (SD) weight changes were not significantly different between insulin degludec and insulin glargine U100 in treatment period 1 (1.5 [4.4] vs 1.8 [4.3] kg, respectively; P = .32) and treatment period 2 (0.5 [5.1] vs 0.9 [3.7] kg, respectively; P = .29).

Adverse Events

In the safety analysis set, 384 of 671 patients (57.2%) receiving insulin degludec and 406 of 665 patients (61.1%) receiving insulin glargine U100 had adverse events. For insulin degludec and insulin glargine U100, adverse event rates were 332.6 and 360.1 events/100 PYE, respectively, and serious adverse event rates were 20.6 and 25.0 events/100 PYE, respectively (eTable 5 in Supplement 1). The most common adverse events (≥5% of patients) with both treatments were nasopharyngitis and upper respiratory tract infection (7.5% and 6.6% with insulin degludec and 6.2% and 5.6% with insulin glargine U100, respectively).

There were 7 deaths during the trial, comprising 2 with insulin degludec (both cardiovascular-related deaths) and 5 with insulin glargine U100 (1 cardiovascular-related death, 1 with undetermined cause, 1 due to hepatobiliary causes, and 2 due to malignant neoplasms). One death (sepsis and hepatobiliary causes) was assessed by the investigator as possibly product related (insulin glargine U100). There were a total of 17 major adverse cardiovascular events, comprising 8 with insulin degludec (5 myocardial infarctions and 3 strokes) and 9 with insulin glargine U100 (4 myocardial infarctions, 1 stroke, 1 death with undetermined cause, and 3 cases of unstable angina pectoris). During follow-up, an additional 5 confirmed major adverse cardiovascular events occurred (insulin degludec: 2 cardiovascular-related deaths, 1 nonfatal stroke; insulin glargine U100: 1 cardiovascular-related death and 1 nonfatal stroke).

There were no clinically relevant differences in physical examination results, blood pressure, pulse, electrocardiogram findings, ophthalmoscopic examination findings, or biochemical parameters between treatments.

Discussion

In this double-blind, randomized, treat-to-target crossover trial, treatment with insulin degludec compared with insulin glargine U100 resulted in a statistically significant and clinically meaningful reduction in the rate of overall symptomatic hypoglycemia and nocturnal symptomatic hypoglycemia during the 16-week maintenance period. The hypoglycemia findings were consistent when analyzed over the full treatment period, and they showed a statistically significantly lower rate of severe hypoglycemia with insulin degludec. The magnitude of the hypoglycemia reduction observed with insulin degludec vs insulin glargine U100 is comparable to that reported in earlier trials comparing NPH insulin with insulin detemir or insulin glargine U100.

Hypoglycemia is a problem for many insulin-treated patients with T2D, and its frequency and severity tend to increase with disease progression. Hypoglycemia in general, but especially severe hypoglycemia, represents one of the most concerning complications of insulin therapy and is also a financial burden for the health care system.

Overall, the hypoglycemia results achieved in this trial confirm those from the randomized, parallel, open-label, treat-to-target trials in the phase 3a program for insulin degludec compared with insulin glargine U100. In the current trial and the phase 3a trials, insulin degludec and insulin glargine U100 were titrated to the same fasting blood glucose target (71-90 mg/dL) and reached an equivalent, noninferior HbA1c level. However, this trial used a more specific hypoglycemia definition, including only episodes that were severe or had symptoms accompanied by a blood glucose measurement less than 56 mg/dL, and a timing of insulin administration was applied to avoid confounding interpretation of the hypoglycemia data. Moreover, the trial was conducted in a patient population more closely resembling that encountered in clinical practice, including individuals with moderate chronic renal failure, hypoglycemia unawareness, and recurrent hypoglycemia. Thus, the rates of severe hypoglycemia observed in this trial were higher than in the phase 3a program.

The rates of severe hypoglycemia were also higher compared with those in the parallel, open-label, treat-to-target trial examining the risk of hypoglycemia for insulin glargine U300 (a 300-U/mL formulation of glargine with a half-life of 19 hours) vs insulin glargine U100. In the EDITION 2 study, a significant hypoglycemia risk reduction with insulin glargine U300 vs insulin glargine U100 was primarily observed in the titration phase and could have been due to the described lower potency of insulin glargine U300, which may lead to a more protracted titration phase.

This trial has several limitations. First, the intensive monitoring in the trial setting may have increased the frequency with which hypoglycemia data were collected and reported compared with an actual clinical setting. However, this intensive monitoring may have provided a more accurate representation of hypoglycemia rates in the population, including those with recurrent hypoglycemia, than those derived from observational studies or randomized clinical trials from which such patients are typically excluded. Second, the first choice of treatment for the trial population in a clinical setting may not have been once-daily basal insulin. However, during the maintenance period, glycemic control approached the guideline targets. Third, the complication of handling rescue therapy for patients not at target glycemic control who were in need of bolus insulin was not included in this trial. Fourth, the higher-than-expected withdrawal rate may have resulted from the demanding nature of the trial, including the 64-week duration, 2 different treatments, and the use of vials and syringes. Fifth, the crossover design may induce a potential carryover effect. However, specifying the primary and secondary end points during the maintenance period aimed to eliminate the carryover effect of previous insulin treatment following the 16-week washout and titration period on hypoglycemic episodes.

Conclusions

Among patients with type 2 diabetes treated with insulin and with at least 1 hypoglycemia risk factor, 32 weeks’ treatment with insulin degludec vs insulin glargine U100 resulted in a reduced rate of overall symptomatic hypoglycemia.

eFigure 1. Trial design

eFigure 2. Hypoglycemia definition

eFigure 3. Hierarchical testing procedure

eFigure 4. Sensitivity analyses – maintenance period

eFigure 5. Fasting plasma glucose (A) and pre-breakfast self-measured blood glucose (B) over time

eTable 1. Titration algorithm

eTable 2. Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities (MedDRA) predefined search of safety data

eTable 3. Multiple imputation tipping analysis for primary endpoint

eTable 4. Insulin dose

eTable 5. Adverse events

Trial Protocol

Statistical Analysis Plan

References

- 1.Frier BM. How hypoglycaemia can affect the life of a person with diabetes. Diabetes Metab Res Rev. 2008;24(2):87-92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Leiter LA, Yale JF, Chiasson JL, Harris S, Kleinstiver P, Sauriol L. Assessment of the impact of fear of hypoglycemic episodes on glycemic and hypoglycemia management. Can J Diabetes. 2005;29(3):186-192. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stratton IM, Adler AI, Neil HAW, et al. Association of glycaemia with macrovascular and microvascular complications of type 2 diabetes (UKPDS 35): prospective observational study. BMJ. 2000;321(7258):405-412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Holman RR, Paul SK, Bethel MA, Matthews DR, Neil HA. 10-Year follow-up of intensive glucose control in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2008;359(15):1577-1589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nathan DM, Buse JB, Davidson MB, et al. ; American Diabetes Association; European Association for Study of Diabetes . Medical management of hyperglycemia in type 2 diabetes: a consensus algorithm for the initiation and adjustment of therapy: a consensus statement of the American Diabetes Association and the European Association for the Study of Diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2009;32(1):193-203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hermansen K, Davies M, Derezinski T, Martinez Ravn G, Clauson P, Home P. A 26-week, randomized, parallel, treat-to-target trial comparing insulin detemir with NPH insulin as add-on therapy to oral glucose-lowering drugs in insulin-naive people with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2006;29(6):1269-1274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Philis-Tsimikas A, Charpentier G, Clauson P, Ravn GM, Roberts VL, Thorsteinsson B. Comparison of once-daily insulin detemir with NPH insulin added to a regimen of oral antidiabetic drugs in poorly controlled type 2 diabetes. Clin Ther. 2006;28(10):1569-1581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Riddle MC, Rosenstock J, Gerich J; Insulin Glargine 4002 Study Investigators . The treat-to-target trial: randomized addition of glargine or human NPH insulin to oral therapy of type 2 diabetic patients. Diabetes Care. 2003;26(11):3080-3086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Heise T, Nosek L, Rønn BB, et al. Lower within-subject variability of insulin detemir in comparison to NPH insulin and insulin glargine in people with type 1 diabetes. Diabetes. 2004;53(6):1614-1620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Haahr H, Heise T. A review of the pharmacological properties of insulin degludec and their clinical relevance. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2014;53(9):787-800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Novo Nordisk Tresiba demonstrated lower day-to-day and within-day variability in glucose-lowering effect compared with insulin glargine U300 [press release]. November 12, 2016. http://www.novonordisk.com/media/news-details.2056385.html. Accessed January 16, 2017.

- 12.Garber AJ, King AB, Del Prato S, et al. ; NN1250-3582 (BEGIN BB T2D) Trial Investigators . Insulin degludec, an ultra-longacting basal insulin, versus insulin glargine in basal-bolus treatment with mealtime insulin aspart in type 2 diabetes (BEGIN Basal-Bolus Type 2): a phase 3, randomised, open-label, treat-to-target non-inferiority trial. Lancet. 2012;379(9825):1498-1507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zinman B, Philis-Tsimikas A, Cariou B, et al. ; NN1250-3579 (BEGIN Once Long) Trial Investigators . Insulin degludec versus insulin glargine in insulin-naive patients with type 2 diabetes: a 1-year, randomized, treat-to-target trial (BEGIN Once Long). Diabetes Care. 2012;35(12):2464-2471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vora J, Christensen T, Rana A, Bain SC. Insulin degludec versus insulin glargine in type 1 and type 2 diabetes mellitus: a meta-analysis of endpoints in phase 3a trials. Diabetes Ther. 2014;5(2):435-446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ratner RE, Gough SC, Mathieu C, et al. Hypoglycaemia risk with insulin degludec compared with insulin glargine in type 2 and type 1 diabetes: a pre-planned meta-analysis of phase 3 trials. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2013;15(2):175-184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.World Medical Association World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki: ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. JAMA. 2013;310(20):2191-2194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.International Conference of Harmonisation ICH harmonised tripartite guideline: guideline for Good Clinical Practice. May 1, 1996. http://www.ich.org/products/guidelines/efficacy/efficacy-single/article/good-clinical-practice.html. Accessed January 16, 2016.

- 18.Seaquist ER, Anderson J, Childs B, et al. Hypoglycemia and diabetes: a report of a workgroup of the American Diabetes Association and the Endocrine Society. Diabetes Care. 2013;36(5):1384-1395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.UK Hypoglycaemia Study Group Risk of hypoglycaemia in types 1 and 2 diabetes: effects of treatment modalities and their duration. Diabetologia. 2007;50(6):1140-1147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Workgroup on Hypoglycemia, American Diabetes Association Defining and reporting hypoglycemia in diabetes: a report from the American Diabetes Association Workgroup on Hypoglycemia. Diabetes Care. 2005;28(5):1245-1249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Donnelly LA, Morris AD, Frier BM, et al. ; DARTS/MEMO Collaboration . Frequency and predictors of hypoglycaemia in type 1 and insulin-treated type 2 diabetes: a population-based study. Diabet Med. 2005;22(6):749-755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Leese GP, Wang J, Broomhall J, et al. ; DARTS/MEMO Collaboration . Frequency of severe hypoglycemia requiring emergency treatment in type 1 and type 2 diabetes: a population-based study of health service resource use. Diabetes Care. 2003;26(4):1176-1180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Curkendall SM, Zhang B, Oh KS, Williams SA, Pollack MF, Graham J. Incidence and cost of hypoglycemia among patients with type 2 diabetes in the United States: analysis of a health insurance database. J Clin Outcomes Manag. 2011;18(10):455-462. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hammer M, Lammert M, Mejías SM, Kern W, Frier BM. Costs of managing severe hypoglycaemia in three European countries. J Med Econ. 2009;12(4):281-290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Becker RHA, Dahmen R, Bergmann K, Lehmann A, Jax T, Heise T. New insulin glargine 300 Units · mL-1 provides a more even activity profile and prolonged glycemic control at steady state compared with insulin glargine 100 Units · mL-1. Diabetes Care. 2015;38(4):637-643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yki-Järvinen H, Bergenstal R, Ziemen M, et al. ; EDITION 2 Study Investigators . New insulin glargine 300 units/mL versus glargine 100 units/mL in people with type 2 diabetes using oral agents and basal insulin: glucose control and hypoglycemia in a 6-month randomized controlled trial (EDITION 2). Diabetes Care. 2014;37(12):3235-3243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sanovi-Aventis Toujeo prescribing information. 2015. https://www.toujeo.com/. Accessed January 16, 2017.

- 28.American Diabetes Association Standards of medical care in diabetes—2017. Diabetes Care. 2017;40(suppl 1):S1-S133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eFigure 1. Trial design

eFigure 2. Hypoglycemia definition

eFigure 3. Hierarchical testing procedure

eFigure 4. Sensitivity analyses – maintenance period

eFigure 5. Fasting plasma glucose (A) and pre-breakfast self-measured blood glucose (B) over time

eTable 1. Titration algorithm

eTable 2. Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities (MedDRA) predefined search of safety data

eTable 3. Multiple imputation tipping analysis for primary endpoint

eTable 4. Insulin dose

eTable 5. Adverse events

Trial Protocol

Statistical Analysis Plan