Key Points

Question

Can the morphologic characteristics of a café au lait macule help predict response to treatment with pigment lasers?

Findings

In this retrospective case series of 45 patients, irregularly bordered lesions on average achieved a mean visual analog scale score of 3.67 (range, 1-4), corresponding to excellent clearance, while smooth-bordered lesions achieved a mean score of 1.76, corresponding to fair clearance, a significant difference.

Meaning

Pigment lasers are more effective at clearing irregularly bordered lesions than smooth-bordered lesions, a distinction that can be used clinically to help predict response and manage expectations.

Abstract

Importance

Response to laser treatment for café au lait macules (CALMs) is inconsistent and difficult to predict.

Objective

To test the hypothesis that irregularly bordered CALMs of the “coast of Maine” subtype respond better to treatment than those of the smooth-bordered “coast of California” subtype.

Design, Setting, and Participants

This retrospective case series included patients from 2 multiple-clinician US practices treated from 2005 through 2016. All patients had a clinical diagnosis of CALM and were treated with a Q-switched or picosecond laser. A total of 51 consecutive patients were eligible, 6 of whom were excluded owing to ambiguous lesion subtype. Observers were blinded to final patient groupings.

Exposures

Treatment with 755-nm alexandrite picosecond laser, Q-switched ruby laser, Q-switched alexandrite laser, or Q-switched 1064-nm Nd:YAG laser.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Main outcome was grade in a visual analog scale (VAS) consisting of 4 levels of treatment response: poor (grade 1, 0%-25% improvement), fair (grade 2, 26%-50% improvement), good (grade 3, 51%-75% improvement), and excellent (grade 4, 76%-100% improvement).

Results

Forty-five patients were included in the series, 19 with smooth-bordered lesions and 26 with irregularly bordered lesions. Thirty-four (76%) of the participants were female; 33 (73%) were white; and the mean age at the time of laser treatment was 14.5 years (range, 0-44 years). Smooth-bordered lesions received a mean VAS score of 1.76, corresponding to a fair response on average (26%-50% pigmentary clearance). Irregularly bordered lesions received a mean VAS score of 3.67, corresponding to an excellent response on average (76%-100% clearance) (P < .001).

Conclusions and Relevance

CALMs with jagged or ill-defined borders of the coast of Maine subtype tend to respond well to laser treatment, whereas those with smooth and well-defined borders of the coast of California subtype tend to have poor response. Clinicians using Q-switched or picosecond lasers to treat CALMs can use morphologic characteristics to help predict response and more effectively manage patient expectations.

This case series compares the responses of café au lait lesions to laser treatment based on their morphologic characteristics, ie, ill-defined vs well-defined borders.

Introduction

Café au lait macules (CALMs) are common lesions arising in early life in about 15% of the population. While CALM is usually an isolated finding (eg, the patients in the present study had only 1 CALM each), multiple lesions in a patient may be associated with one of several genodermatoses, including neurofibromatosis. McCune-Albright syndrome is associated with a singular lesion that is characteristically large, unilateral, and with irregular borders. In dermatologic texts, the asymmetric and irregular borders of lesions associated with McCune-Albright syndrome are likened to the coast of Maine, while the smooth borders of those associated with neurofibromatosis are likened to the coast of California.

CALMs may be cosmetically troubling to patients. Anecdotal reports and case series suggest that laser therapy yields inconsistent results. Recently, quality-switched (Q-switched) 1064-nm neodymium-doped yttrium aluminum garnet (Nd:YAG) laser achieved good to excellent clearance in 74.4% of patients. In other series, response has been more inconsistent, with rates of 20% to 57%. Other lasers represented include the copper vapor laser, frequency-doubled Q-switched Nd:YAG, Q-switched ruby laser, Q-switched alexandrite laser, erbium-doped YAG, and pulsed-dye laser. In these studies, there was a 15% to 41% incidence of dyspigmentation or scar.

There has been little exploration to our knowledge as to how morphologic characteristics might affect treatment response. Size may to some extent predict response, with smaller lesions easier to clear. The idea that morphology or distribution may affect response to laser treatment has been explored previously in capillary malformations. Evidence of this sort is helpful for practitioners and patients. We performed a retrospective medical record and photographic review to evaluate the efficacy of pigment lasers on CALMs and to isolate a morphologic criterion by which to predict response.

Methods

Medical records were reviewed of patients with clinical diagnoses of CALM who were treated from 2005 through 2016 with 755-nm alexandrite picosecond laser (PicoSure; Cynosure), 694-nm ruby nanosecond laser (Sinon; Alma Lasers), 755-nm alexandrite nanosecond laser (Trivantage; Syneron Candela), or 1064-nm Nd:YAG nanosecond laser (Spectra; Lutronic). Inclusion required appropriate quality photographic documentation before and after treatment. The Asentral Institutional Review Board, Newbury, Massachusetts, approved the study protocol, waiving patient written informed consent for the retrospective analysis.

The Table includes information extracted from each medical record. Clinical photographs before the first procedure and after the last (or the last for which there is a high-quality postprocedure photograph) were evaluated using side-by-side comparisons by 4 physicians who were blinded to final morphologic category. Posttreatment photographs were taken at least 1 month after treatment. The physicians first identified the morphologic subtype of each CALM (irregularly bordered coast of Maine vs smooth-bordered coast of California) and then assessed improvement using a visual analog scale (VAS) consisting of 4 levels of treatment response: poor (grade 1, 0%-25% improvement), fair (grade 2, 26%-50% improvement), good (grade 3, 51%-75% improvement), and excellent (grade 4, 76%-100% improvement). Lesions were excluded from the analysis if they received consensus from fewer than 3 of the 4 physicians regarding morphologic subtype.

Table. Patient Demographic and Clinical Characteristics.

| Characteristic | Lesion Subtype | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Smooth-Bordered | Irregularly Bordered | ||

| Participants, No. (%) | 19 (42) | 26 (58) | NA |

| Male | 4 (21) | 7 (27) | .74 |

| Female | 15 (79) | 19 (73) | |

| Mean age at time of laser treatment, y | 13.4 | 15.4 | .60 |

| Fitzpatrick skin type, No. (%) | |||

| I-III | 14 (74) | 19 (73) | >.99 |

| IV-V | 5 (26) | 7 (27) | |

| Distribution of lesions, No. (%) | |||

| Face | 14 (74) | 23 (88) | .25 |

| Trunk or extremities | 5 (26) | 3 (12) | |

| No. of treatments per patient, mean (SD) | 6.74 (8.43) | 4.56 (3.36) | .69 |

| Laser type, No. (%) | |||

| Q-switched | 18 | 25 | .31 |

| Picosecond | 3 | 1 | |

| Lesion size, No. (%) | |||

| <16 cm2 | 11 (58) | 12 (46) | .55 |

| ≥16 cm2 | 8 (42) | 14 (54) | |

| Posttreatment VAS improvement score | 1.76 (Fair) | 3.67 (Excellent) | .001 |

Abbreviation: VAS, visual analog scale.

Statistical analysis was performed using the Fisher exact test for comparison of categorical variables and the Wilcoxon rank sum test for other calculations. P < .05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

The clinical characteristics of the study patients are summarized in the Table. Fifty-one patients were evaluated for study inclusion, and 45 were included in the analysis: 19 with smooth-bordered lesions and 26 with irregularly bordered lesions. Six patients were excluded owing to ambiguous subtype of their lesions. As supported by the data reported in the Table, there was no significant difference between the irregularly bordered and smooth-bordered lesion groups in terms of sex, mean age at time of first laser treatment, number of patients with skin of color, distribution of lesions, mean number of treatments, and Q-switched vs picosecond technology. The mean age at time of laser treatment was 14.5 years (range, 0-44 years) overall. The most common Fitzpatrick skin type was III in both subtype groups. Most patients were treated with the Q-switched ruby laser, although Q-switched alexandrite and Nd:YAG were also used. Only 1 lesion in each group was treated with a picosecond device alone. In a few cases, more than 1 type of laser was used.

The mean VAS score of all lesions was 2.87, corresponding to about 50% to 75% improvement. Smooth-bordered lesions received a mean VAS score of 1.76, corresponding to a fair response on average (26%-50% clearance) (Figure 1). Irregularly bordered lesions received a mean VAS score of 3.67, corresponding to an excellent response on average (76%-100% clearance) (Figure 2). This difference was statistically significant (P < .001). Averaging the rankings of the 4 evaluators, we found that an average of 80% of irregularly bordered lesions achieved excellent response (n = 20.75), and 5% had poor response (n = 1.25), whereas 8% of smooth-bordered lesions achieved excellent response (n = 1.5), and 54% had poor response (n = 10.25). While the majority of smooth-bordered lesions (78%; n = 14.75) had less than 50% improvement, the majority of irregularly bordered lesions (93%; n = 24.0) had greater than 50% improvement.

Figure 1. Treatment of a Coast of California (Smooth-Bordered) Café au Lait Macule on the Face.

Comparison of the pretreatment photograph (A) and the posttreatment photograph (B) shows poor clearance after 3 treatments with a Q-switched 694-nm laser.

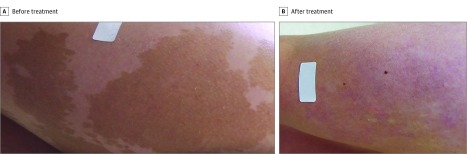

Figure 2. Treatment of a Coast of Maine (Irregularly Bordered) Café au Lait Macule on the Thigh.

Comparison of the pretreatment photograph (A) and the posttreatment photograph (B) shows excellent clearance after 3 treatments with a Q-switched 694-nm laser.

In accordance with Kim et al, we also compared facial vs nonfacial lesions and smaller (<16 cm2) vs larger (≥16 cm2) lesions. There was a trend toward improved clearance in facial lesions (2.95 vs 2.47; P = .33) and smaller lesions (2.95 vs 2.78; P = .58), but the differences were not significant.

Adverse effects were expected and included mild transient posttreatment pain, edema, and crust formation. Postinflammatory hypopigmentation occurred in 1 irregularly bordered lesion (4%) and 4 smooth-bordered lesions (21%), which was not statistically significant. Postinflammatory hyperpigmentation was impossible to distinguish from residual nevus. However, any residual hyperpigmentation was taken into account in the assessment of improvement.

Discussion

CALMs are unpredictable lesions to treat. In this study, we have shown that morphologic subtype is highly predictive of response to laser treatment. Irregularly bordered coast of Maine lesions were far more likely to achieve good or excellent clearance than smooth-bordered coast of California lesions. Furthermore, there was a trend toward higher risk of hypopigmentation in smooth-bordered lesions. This study is the first to our knowledge to explore differences in these 2 subtypes in genetically unaffected individuals and beyond their diagnostic value.

Limitations

Several limitations are present. The study was not powered to detect comparisons among various laser modalities. Morphologic classification is to some extent subjective, but we attempted to limit subjectivity by including only lesions for which at least 3 of 4 physicians agreed. Though blinded to final agreed category, because physicians had to first classify each lesion, bias could exist in their assessment of improvement. Because the study was retrospective, there was no standard follow-up period, and therefore rates of recurrence could not be accurately assessed. However, any recurrence present in the posttreatment photograph was reflected in the physician’s assessment.

Conclusions

From our results, we counsel patients with CALM on the basis of their morphologic subtype. For smooth-bordered lesions, a large number of treatments may be needed for only mild improvement. Further study is needed, perhaps with histologic examination, to help determine the mechanism for this differential response. Presumably, there are histologic or ultrastructural differences among these lesions. Nevertheless, having a clinical tool by which to predict response helps us (1) to better counsel our patients, who are often eager for prognostic information, and (2) to better understand our outcomes.

References

- 1.Kopf AW, Levine LJ, Rigel DS, Friedman RJ, Levenstein M. Prevalence of congenital-nevus-like nevi, nevi spili, and café au lait spots. Arch Dermatol. 1985;121(6):766-769. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Landau M, Krafchik BR. The diagnostic value of café-au-lait macules. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999;40(6, pt 1):877-890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McLean DI, Gallagher RP. “Sunburn” freckles, café-au-lait macules, and other pigmented lesions of schoolchildren: the Vancouver Mole Study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1995;32(4):565-570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Davies JH, Barton JS, Gregory JW, Mills C. Infantile McCune-Albright syndrome. Pediatr Dermatol. 2001;18(6):504-506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Paller A, Mancini AJ, Hurwitz S. Hurwitz Clinical Pediatric Dermatology. 4th ed New York, NY: Elsevier Saunders; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kim HR, Ha JM, Park MS, et al. A low-fluence 1064-nm Q-switched neodymium-doped yttrium aluminium garnet laser for the treatment of café-au-lait macules. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;73(3):477-483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Somyos K, Boonchu K, Somsak K, Panadda L, Leopairut J. Copper vapour laser treatment of café-au-lait macules. Br J Dermatol. 1996;135(6):964-968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kilmer SL, Wheeland RG, Goldberg DJ, Anderson RR. Treatment of epidermal pigmented lesions with the frequency-doubled Q-switched Nd:YAG laser: a controlled, single-impact, dose-response, multicenter trial. Arch Dermatol. 1994;130(12):1515-1519. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shimbashi T, Kamide R, Hashimoto T. Long-term follow-up in treatment of solar lentigo and café-au-lait macules with Q-switched ruby laser. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 1997;21(6):445-448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kagami S, Asahina A, Watanabe R, et al. Treatment of 153 Japanese patients with Q-switched alexandrite laser. Lasers Med Sci. 2007;22(3):159-163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wang Y, Qian H, Lu Z. Treatment of café au lait macules in Chinese patients with a Q-switched 755-nm alexandrite laser. J Dermatolog Treat. 2012;23(6):431-436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Alora MB, Arndt KA. Treatment of a café-au-lait macule with the erbium:YAG laser. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2001;45(4):566-568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Alster TS. Complete elimination of large café-au-lait birthmarks by the 510-nm pulsed dye laser. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1995;96(7):1660-1664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nguyen CM, Yohn JJ, Huff C, Weston WL, Morelli JG. Facial port wine stains in childhood: prediction of the rate of improvement as a function of the age of the patient, size and location of the port wine stain and the number of treatments with the pulsed dye (585 nm) laser. Br J Dermatol. 1998;138(5):821-825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Renfro L, Geronemus RG. Anatomical differences of port-wine stains in response to treatment with the pulsed dye laser. Arch Dermatol. 1993;129(2):182-188. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]