Key Points

Question

Does improvisational music therapy improve symptom severity of children with autism spectrum disorder?

Findings

In a randomized clinical trial of 364 children in 9 countries, mean autism severity, as measured on the Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule, social affect domain, over 5 months, was reduced from 14.08 to 13.23 in the improvisational music therapy group and from 13.49 to 12.58 in the enhanced standard care group, which included parent counseling and other available interventions, a nonsignificant mean difference of 0.06.

Meaning

In children with autism spectrum disorder, music therapy did not result in significant improvements in mean symptom scores compared with enhanced standard care.

Abstract

Importance

Music therapy may facilitate skills in areas affected by autism spectrum disorder (ASD), such as social interaction and communication.

Objective

To evaluate effects of improvisational music therapy on generalized social communication skills of children with ASD.

Design, Setting, and Participants

Assessor-blinded, randomized clinical trial, conducted in 9 countries and enrolling children aged 4 to 7 years with ASD. Children were recruited from November 2011 to November 2015, with follow-up between January 2012 and November 2016.

Interventions

Enhanced standard care (n = 182) vs enhanced standard care plus improvisational music therapy (n = 182), allocated in a 1:1 ratio. Enhanced standard care consisted of usual care as locally available plus parent counseling to discuss parents’ concerns and provide information about ASD. In improvisational music therapy, trained music therapists sang or played music with each child, attuned and adapted to the child’s focus of attention, to help children develop affect sharing and joint attention.

Main Outcomes and Measures

The primary outcome was symptom severity over 5 months, based on the Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule (ADOS), social affect domain (range, 0-27; higher scores indicate greater severity; minimal clinically important difference, 1). Prespecified secondary outcomes included parent-rated social responsiveness. All outcomes were also assessed at 2 and 12 months.

Results

Among 364 participants randomized (mean age, 5.4 years; 83% boys), 314 (86%) completed the primary end point and 290 (80%) completed the last end point. Over 5 months, participants assigned to music therapy received a median of 19 music therapy, 3 parent counseling, and 36 other therapy sessions, compared with 3 parent counseling and 45 other therapy sessions for those assigned to enhanced standard care. From baseline to 5 months, mean ADOS social affect scores estimated by linear mixed-effects models decreased from 14.08 to 13.23 in the music therapy group and from 13.49 to 12.58 in the standard care group (mean difference, 0.06 [95% CI, −0.70 to 0.81]; P = .88), with no significant difference in improvement. Of 20 exploratory secondary outcomes, 17 showed no significant difference.

Conclusions and Relevance

Among children with autism spectrum disorder, improvisational music therapy, compared with enhanced standard care, resulted in no significant difference in symptom severity based on the ADOS social affect domain over 5 months. These findings do not support the use of improvisational music therapy for symptom reduction in children with autism spectrum disorder.

Trial Registration

isrctn.org Identifier: ISRCTN78923965

This randomized trial evaluated the effects of improvisational music therapy vs enhanced standard care on generalized social communication skills of children with autism spectrum disorder.

Introduction

Autism spectrum disorder (ASD) is characterized by persistent deficits in social communication and interaction and restricted, repetitive behaviors and interests. ASD affects about 1% of the general population and is associated with substantial disability and economic loss. A variety of approaches to improve the core deficits and lives of people with ASD have been developed, including behavioral, developmental, educational, and medical interventions, but the strength of evidence for reducing autism severity is low for most interventions.

In the first description of autism, Kanner noted that many children with autism had a strong preference for music. Music therapy seeks to exploit the potential of music as a medium for social communication. In improvisational music therapy, client and therapist spontaneously create music using singing, playing, and movement; music is understood in the widest sense. It is a developmental, child-centered approach in which a music therapist follows the child’s focus of attention, behaviors, and interests to facilitate development in the child’s social communicative skills. In 2017 there were about 7000 music therapists in the United States and 6000 in Europe. Randomized trials have suggested positive effects of music therapy on social interaction, joint attention, and parent-child relationships. Evidence on longer-term effects and dose-effect relations is lacking, and evidence that effects observed within therapy sessions generalize to other settings, situations, and people needs confirmation. The objective of this study was to evaluate effects of improvisational music therapy on generalized social communication skills of children with ASD.

Methods

Trial Design

The Trial of Improvisational Music Therapy’s Effectiveness for Children With Autism (TIME-A) was an assessor-blinded, international, multicenter (10 centers), parallel-group, pragmatic randomized clinical trial that compared improvisational music therapy (hereafter referred to as music therapy) added to enhanced standard care (usual care plus parent counseling; hereafter referred to as standard care) with standard care alone for improving social communicative skills in children with ASD. Ethics approval was obtained by the relevant ethics committees in each of the 9 countries (Australia, Austria, Brazil, Israel, Italy, Korea, Norway, United Kingdom, United States). Written informed consent was obtained from parents or guardians. An independent data and safety monitoring committee monitored safety and examined interim efficacy results. The study protocol was published separately and is also available in Supplement 1.

Participants and Trial Procedures

Trial procedures were pilot tested. Children aged 4 years to 6 years, 11 months and meeting criteria for ASD according to the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, Tenth Revision were enrolled between November 2011 and November 2015 and followed up from January 2012 to November 2016. Exclusion criteria were serious sensory disorders (blindness, deafness) and having received music therapy in the last 12 months. Diagnosis was confirmed using the ASD cutoff of the Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule (ADOS) and cutoffs on 2 of the 3 main domains of the Autism Diagnostic Interview–Revised. Cognitive ability was assessed quantitatively using a standardized IQ test or categorically by clinical judgment if the child was unable to complete a formal test. Participating parents or guardians completed the Social Responsiveness Scale (SRS) and two 100-mm visual analog scales for quality of life of the participant and the family. Parents also reported demographics and concomitant treatments. Follow-up assessments at 2, 5, and 12 months after randomization included ADOS, SRS, quality of life, and concomitant treatments; at 12 months, we also assessed success of blinding and reason for potential dropout.

After consent and baseline assessments, participants were randomly assigned to 1 of 3 interventions: low-intensity (once per week) or high-intensity (3 times per week) music therapy added to standard care, or standard care alone, over a period of 5 months. Participants were free to attend any type of treatment or therapeutic interventions but were asked not to attend music therapy outside the study context.

Individuals were randomly assigned according to a computer-generated randomization list with a ratio 1:1:2 (low-intensity music therapy:high-intensity music therapy:standard care), stratified by site and with randomly varying block sizes of 4 and 8, which was prepared by an investigator with no clinical involvement. A coordinator (Ł.B.) with no clinical involvement checked eligibility and baseline data before handing out the randomization via an online system.

All data were stored within an electronic database management system on a secure server with password-controlled access (OpenClinica, version 3.3) and double-entered independently. Changes to the protocol compared with its published version are shown in eTable 1 in Supplement 2.

Interventions

Improvisational music therapy was offered in outpatient settings (clinics, kindergartens, family homes) in 30-minute one-to-one sessions (possibly joined by family members). Depending on the randomization to high- or low-intensity music therapy, either 3 weekly sessions (a higher dose, common in some countries) or 1 weekly session (the de facto standard in many countries) were offered for a period of 5 months, a duration deemed sufficient to notice development. Thirty qualified music therapists (21 women; mean age, 34.7 years [range, 23-55 years]; mean experience as music therapists, 7.3 years [range, 0-30 years]) conducted the therapy, following a set of consensus principles developed for the study. Therapists developed joint musical activities (singing or instrumental play) individually with each child, based on the child’s focus of attention, using improvisation techniques such as synchronizing, mirroring, or grounding. These activities aimed to develop and enhance affect sharing and joint attention, which are associated with development of social competencies in ASD. Sessions were videotaped or audiotaped for assessment of fidelity. Two independent raters assessed 606 randomly selected 3-minute segments from 63 participants.

Enhanced standard care consisted of the routine care available at the site, plus three 60-minute sessions of parent counseling (at 0, 2, and 5 months). Twenty-four professionals experienced with ASD (20 women; clinical psychologists, social workers, or music therapists) offered to discuss parents’ concerns and provide information about ASD, based on principles described in the protocol. The purpose of the design was to provide a minimal intervention and to increase adherence and equipoise. Sessions were videotaped when possible. Parents reported other service use.

Outcomes

The primary outcome was the social affect score of the ADOS, a measure of autism symptom severity, over 5 months. The ADOS is a semistructured, standardized observation instrument. Designed as a diagnostic tool, it has also been used to measure intervention outcomes. One of 3 modules and 1 of 5 scoring algorithms was chosen, depending on language abilities and age. Of a total of 28 to 31 ADOS items, 10 are used to calculate the ADOS social affect score. Items can range from 0 to 2 or 3; in line with an earlier trial, the full range of item scores from 0 to 3 was retained to improve sensitivity to change. We applied the same module across time points for each child to ensure consistency. The ADOS social affect score, constructed as the sum of the relevant items for the social affect domain, can range from 0 to 27 (in module 3; 0-24 in modules 1 and 2), with higher scores indicating greater severity. We assumed a minimal clinically important difference (MCID) of 1 point. We used the most current version available in all countries and languages. Formal training in ADOS assessments was available in some but not all countries. All assessors in Australia, Korea, and the United Kingdom had completed research-level qualification (the highest level); those in Israel, Italy, Norway, and the United States had at least clinical-level qualification (the basic level). In Austria and Brazil, no certification was available, but we used experienced ADOS raters. Of the 23 assessors, 10 had research training and 10 had clinical training. We used assessors from a different location who were not normally involved with the child to ensure blinding. Success of blinding was verified by asking assessors if and how they had discovered the child’s allocation.

Prespecified secondary outcomes were the ADOS social affect score over 2 and 12 months and the SRS total scale and its 5 subscales over 2, 5, and 12 months. The SRS is a parent-rated measure and was therefore not blinded. A total of 65 items (each ranging from 0 [“not true”] to 3 [“almost always true”]) assess the severity of ASD symptoms occurring in natural social settings, as observed by parents, for a total score of 0 to 195. A score of 85 or above provides strong evidence of the presence of an ASD and is recommended for clinical settings. The subscales are social awareness (8 items), social cognition (12), social communication (22), social motivation (11), and autistic mannerisms (12). An additional outcome, cost-effectiveness, will be reported separately.

Post hoc outcomes, all at 2, 5, and 12 months, included the ADOS total score and subscales; two 100-mm visual analog scales for parent-reported quality of life of the child and of the family as a whole (0 = worst to 100 = best possible quality of life); and parent-reported adverse events including hospitalization.

Statistical Analyses

The study was originally conceived as a group sequential design with 4 interim analyses but was stopped after the first prespecified analysis (see Results). Power was calculated for the 2-group comparison to detect an MCID of 1 point for ADOS social affect score. Although there is no consensus MCID for this outcome, a 1-point difference in ADOS social affect score (typical SD, ≈5) was chosen because it would correspond to Cohen d = 0.20 (a small effect size). Previous music therapy trials had found effect sizes of d = 0.50 for gestural and d = 0.36 for verbal communicative skills, whereas a larger trial of another intervention had found an effect size of d = 0.24 on the ADOS. As conducted, the study had 42% power to detect a difference of 1 point, or 80% power for a difference of 1.6 points.

The main statistical analysis followed a modified intention-to-treat (ITT) principle, including all participants who had data for at least 1 follow-up time point in the group to which they had originally been randomized. Analyses compared mean change on the primary outcome in longitudinal models, following confirmation of normality. We calculated linear mixed-effects models with maximum likelihood estimation, both unadjusted and adjusted for site as a random effect, for the main 2-group comparison and the additional 3-group comparison including intensity of music therapy, with treatment effects represented as interaction effects (time × group). Sensitivity analyses for the primary outcome and comparison tested the influence of missing data (linear models on 50 data sets multiply imputed using diagnosis, age, and site) and therapist effects (linear mixed-effects model with music therapist as a random effect nested within site). Prespecified subgroup analyses were conducted for age and ASD subtype, using linear models with interaction tests.

Secondary outcomes were analyzed using linear mixed-effects models. Because no adjustments for multiple testing were made, all secondary outcomes were regarded as exploratory. No statistical analysis was conducted for exploratory adverse events.

In a post hoc responder analysis, we compared the proportion of participants who improved by at least the MCID for the ADOS social affect score at 5 months. In this binary ITT analysis, we included all participants randomized, assuming no improvements for missing data. We calculated risk ratios with 2-sided 95% confidence intervals using Wald unconditional maximum likelihood estimation for the ITT sample and the per-protocol sample. All tests were 2-sided, with a significance level of 5%. All statistical analyses were conducted using R version 3.3.1 (http://www.r-project.org).

Results

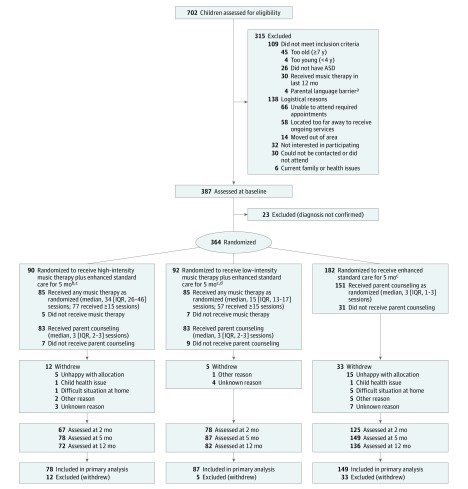

Of 702 children assessed for eligibility, 315 (109 ineligible; 206 declined) were excluded prior to baseline assessments, and another 23 were found ineligible at baseline, before randomization. A total of 364 participants were randomized to music therapy or standard care (182 participants each) (Figure 1). Of the 182 children enrolled to music therapy, 90 were randomized to high-intensity music therapy and 92 to low-intensity music therapy. The data and safety monitoring committee examined the first interim efficacy analysis in September 2015. Although the formal criterion for early stopping was not met, the study team decided to stop recruitment, in a decision that included considerations of limited funding and therefore limited likelihood of successful and timely additional recruitment.

Figure 1. Flow of Participants Through the Study.

Numbers assessed are based on valid data for the primary outcome. The intermediate assessment at 2 months was optional at UK sites. ASD indicates autism spectrum disorder; IQR, interquartile range.

aRefers to migrant families unable to complete questionnaires or complete clinical interviews because of insufficient command of the country’s main language(s).

bHigh-intensity music therapy comprised 3 music therapy sessions per week (up to 60 sessions).

cEnhanced standard care comprised parent counseling (3 sessions) plus usual care.

dLow-intensity music therapy comprised 1 music therapy session per week (up to 20 sessions).

Baseline characteristics were well balanced between groups (Table 1). Of the 364 participants, 302 were boys, 301 were diagnosed with childhood autism, and 165 had low cognitive levels (IQ <70). Twelve participants (3%) had prior experience with music therapy. Fifty participants (14%) were lost to the 5-month follow-up (Figure 1). Baseline characteristics of those who dropped out at 5 months were similar to those who were followed up (eTable 2 in Supplement 2).

Table 1. Baseline Characteristics of the Sample.

| Characteristics | Enhanced Standard Care | Improvisational Music Therapy | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| High Intensity | Low Intensity | |||||

| No. | Value | No. | Value | No. | Value | |

| Age, mean (SD), y | 182 | 5.4 (0.9) | 90 | 5.4 (0.9) | 92 | 5.5 (0.8) |

| Boys, No. (%) | 182 | 149 (81.9) | 90 | 78 (86.7) | 92 | 71 (77.2) |

| Native speaker of the country’s main language, No. (%) | 182 | 152 (83.5) | 90 | 78 (86.7) | 92 | 74 (80.4) |

| Maternal education, No. (%) | 180 | 89 | 89 | |||

| <12 y (less than high school) | 17 (9.4) | 9 (10.1) | 10 (11.2) | |||

| ≥12 y (equivalent to high school) | 64 (35.6) | 37 (41.6) | 31 (34.8) | |||

| University | 84 (46.7) | 38 (42.7) | 42 (47.2) | |||

| Unknown | 15 (8.3) | 5 (5.6) | 6 (6.7) | |||

| Paternal education, No. (%) | 178 | 87 | 89 | |||

| <12 y (less than high school) | 27 (15.2) | 11 (12.6) | 12 (13.5) | |||

| ≥12 y (equivalent to high school) | 54 (30.3) | 33 (37.9) | 28 (31.5) | |||

| University | 77 (43.3) | 34 (39.1) | 40 (44.9) | |||

| Unknown | 20 (11.2) | 9 (10.3) | 9 (10.1) | |||

| Maternal employment, No. (%) | 180 | 89 | 89 | |||

| Unemployed or social support | 29 (16.1) | 10 (11.2) | 9 (10.1) | |||

| Working part time | 41 (22.8) | 29 (32.6) | 22 (24.7) | |||

| Working full time | 36 (20.0) | 13 (14.6) | 18 (20.2) | |||

| Homemaker | 61 (33.9) | 30 (33.7) | 32 (36) | |||

| Other | 2 (1.1) | 3 (3.4) | 2 (2.2) | |||

| Unknown | 11 (6.1) | 4 (4.5) | 6 (6.7) | |||

| Paternal employment, No. (%) | 179 | 88 | 89 | |||

| Unemployed or social support | 7 (3.9) | 9 (10.2) | 3 (3.4) | |||

| Working part time | 11 (6.1) | 5 (5.7) | 2 (2.2) | |||

| Working full time | 136 (76.0) | 58 (65.9) | 70 (78.7) | |||

| Homemaker | 2 (1.1) | 0 | 3 (3.4) | |||

| Other | 5 (2.8) | 4 (4.5) | 2 (2.2) | |||

| Unknown | 18 (10.1) | 12 (13.6) | 9 (10.1) | |||

| Adults in household, No. (%) | 174 | 87 | 84 | |||

| 1 | 21 (12.1) | 17 (19.5) | 9 (10.7) | |||

| 2 | 137 (78.7) | 62 (71.3) | 72 (85.7) | |||

| >2 | 16 (9.2) | 8 (9.2) | 3 (3.6) | |||

| Siblings in family, No. (%) | 172 | 87 | 83 | |||

| None | 56 (32.6) | 16 (18.4) | 18 (21.7) | |||

| 1 | 77 (44.8) | 43 (49.4) | 43 (51.8) | |||

| >1 | 39 (22.7) | 28 (32.2) | 22 (26.5) | |||

| Diagnosis, No. (%) | 182 | 90 | 92 | |||

| Childhood autism (ICD-10 code F84.0) | 151 (83.0) | 78 (86.7) | 72 (78.3) | |||

| Atypical autism (ICD-10 code F84.1) | 3 (1.6) | 0 | 0 | |||

| Asperger syndrome (ICD-10 code F84.5) | 8 (4.4) | 2 (2.2) | 4 (4.3) | |||

| PDD (ICD-10 code F84.9) | 20 (11.0) | 10 (11.1) | 16 (17.4) | |||

| Previous music therapy, No. (%) | 177 | 8 (4.5) | 89 | 7 (7.9) | 90 | 1 (1.1) |

| ADOSa | ||||||

| Module, No. (%) | 182 | 90 | 92 | |||

| 1 | 103 (56.6) | 65 (72.2) | 56 (60.9) | |||

| 2 | 73 (40.1) | 25 (27.8) | 31 (33.7) | |||

| 3 | 6 (3.3) | 0 | 5 (5.4) | |||

| Score, mean (SD) | ||||||

| Total | 181 | 17.4 (5.2) | 90 | 18.3 (5.1) | 92 | 17.7 (5.7) |

| Social affect | 182 | 13.5 (4.3) | 90 | 14.4 (4.5) | 92 | 13.8 (4.5) |

| Language and communication | 182 | 3.3 (1.4) | 90 | 3.4 (1.5) | 92 | 3.3 (1.6) |

| Reciprocal social interaction | 182 | 10.2 (3.5) | 90 | 11.0 (3.5) | 92 | 10.4 (3.7) |

| Restricted and repetitive behavior | 181 | 3.9 (2.0) | 90 | 3.9 (2.0) | 92 | 3.9 (2.2) |

| SRS score, mean (SD)b | ||||||

| Total | 179 | 96.1 (29.5) | 89 | 95.5 (26.1) | 91 | 96.5 (28.5) |

| Social awareness | 181 | 12.4 (4.1) | 90 | 12.2 (3.6) | 92 | 12 (4.1) |

| Social cognition | 182 | 18.7 (5.9) | 90 | 18 (5.3) | 92 | 18.4 (6.5) |

| Social communication | 182 | 32.1 (10.1) | 90 | 31.9 (9.8) | 92 | 32.4 (10.6) |

| Social motivation | 182 | 15 (6.2) | 90 | 15 (5.0) | 92 | 14.6 (5.7) |

| Autistic mannerisms | 182 | 17.6 (7.1) | 90 | 18.1 (7.3) | 92 | 18.7 (6.9) |

| Quality of life, mean (SD)c | ||||||

| Participant | 181 | 71.1 (18.7) | 88 | 72.3 (18.5) | 88 | 71.9 (18.5) |

| Family | 181 | 68 (19.4) | 87 | 68.7 (21.2) | 89 | 67.8 (19.6) |

| Parent working reduced hours due to the child’s needs (in percent of full-time work), mean (SD) | 101 | 69.1 (31.1) | 42 | 67.9 (29.6) | 38 | 69.5 (30.5) |

| IQ source, No. (%)d | 182 | 90 | 92 | |||

| KABC | 3 (1.6) | 3 (3.3) | 2 (2.2) | |||

| Other standardized test | 107 (58.8) | 50 (55.6) | 53 (57.6) | |||

| Clinical judgment | 72 (39.6) | 37 (41.1) | 37 (40.2) | |||

| IQ, standardized test, mean (SD)e | 108 | 76.1 (27.4) | 50 | 73.4 (27.5) | 53 | 75.9 (22.7) |

| Mental retardation (IQ <70), No. (%) | 180 | 84 (46.7) | 87 | 44 (50.6) | 89 | 40 (44.9) |

| ADI-R score, mean (SD)f | ||||||

| Reciprocal social interaction | 182 | 18.2 (5.8) | 90 | 18.8 (5.6) | 92 | 18.0 (5.9) |

| Language and communication | 182 | 13.1 (4.3) | 90 | 13.3 (4.2) | 92 | 12.5 (4.0) |

| Repetitive behaviors and interests | 182 | 5.9 (2.5) | 90 | 5.9 (2.4) | 92 | 5.8 (2.1) |

| Early onset | 182 | 3.9 (1.1) | 90 | 4.1 (1.0) | 92 | 4 (1.1) |

| Child care, No. (%) | 182 | 90 | 92 | |||

| Attends school | 112 (61.5) | 56 (62.2) | 61 (66.3) | |||

| Full-time care (≥7 h/d) | 40 (22.0) | 19 (21.1) | 21 (22.8) | |||

| Part-time care (<7 h/d) | 19 (10.4) | 13 (14.4) | 6 (6.5) | |||

| None of the above | 11 (6.0) | 2 (2.2) | 4 (4.3) | |||

Abbreviations: ADI-R, Autism Diagnostic Interview–Revised; ADOS, Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule; ICD-10, International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, Tenth Revision; KABC, Kaufman Assessment Battery for Children; SRS, Social Responsiveness Scale; PDD, pervasive developmental disorder unspecified.

Higher scores indicate greater severity (ranges of possible scores: total, 0-37; social affect, 0-27; language and communication, 0-9; reciprocal social interaction, 0-19; restricted and repetitive behavior, 0-10).

Higher scores indicate greater severity (ranges of possible scores: total, 0-195; social awareness, 0-24; social cognition, 0-36; social communication, 0-66; social motivation, 0-33; autistic mannerisms, 0-36).

Assessed using visual analog scale. Higher scores indicate better quality of life (range of possible scores, 0-100; 0 indicates worst possible and 100 best possible quality of life).

IQ was assessed with standardized scales. If the child was unable to complete a standardized test, no quantitative IQ assessment was made, but only a categorical clinical judgment whether mental retardation (ie, IQ <70) was present.

Higher scores indicate greater cognitive ability. Scores around 100 indicate normal intelligence; scores below 70 indicate mental retardation.

Higher scores indicate greater severity (ranges of possible scores: reciprocal social interaction, 0-30; language and communication, 0-26; repetitive behaviors and interests, 0-12; early onset, 0-5).

Blinding of assessors was broken unintentionally for 20 participants (15 in the music therapy group and 5 in the standard care group), usually due to a parent or other person inadvertently mentioning the intervention. There was no evidence of broken or subverted allocation concealment (eFigure 1 in Supplement 2).

Concomitant interventions, provided as part of standard care, included speech and language therapy or communication training (58%), sensory-motor therapy (including occupational therapy and physiotherapy [41%]), and a number of other therapies, which often continued over the course of the trial (eTable 3 in Supplement 2). The median number of sessions of all concomitant interventions (not including parent counseling or improvisational music therapy) over the 5-month intervention period was 45 in those allocated to standard care, compared with 36 sessions in those allocated to music therapy (high-intensity music therapy, 31; low-intensity music therapy, 40). The parents of 317 (87%) of all participants participated in counseling; the median number of sessions was 3 in all groups (Figure 1); fidelity was adequate (eTable 4A in Supplement 2).

Of those allocated to music therapy, 171 (94%) received music therapy, with a median of 19 sessions over the 5-month period (high-intensity music therapy, 34; low-intensity music therapy, 15) (Figure 1). Missed sessions were typically attributable to holidays or illness (eFigure 2 in Supplement 2). However, some parents had difficulties bringing their child to therapy 3 times a week. Treatment fidelity according to the improvisational music therapy manual was overall adequate in the majority of sessions (eTable 4 and eFigure 3 in Supplement 2). Of those allocated to standard care, none received music therapy during the 5-month intervention period. However, 1% in each group received music therapy outside the study before the 12-month follow-up (Figure 1).

Primary Outcome

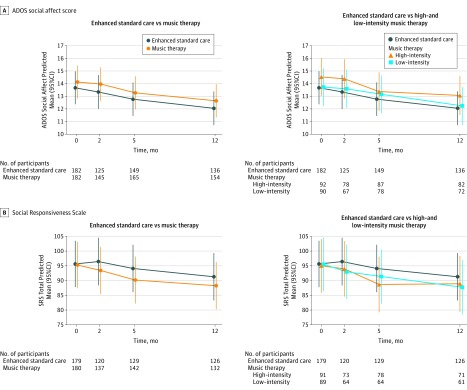

From baseline to 5 months, mean scores of ADOS social affect estimated by linear mixed-effects models decreased from 14.08 to 13.23 in the music therapy group and from 13.49 to 12.58 in the standard care group (mean difference, music therapy vs standard care, 0.06 [95% CI, −0.70 to 0.81]; P = .88), with no significant difference in improvement (eTable 5 in Supplement 2). The observed means (Table 2) differ slightly from those estimated with linear mixed-effects models, which use data from all time points at once. Differences in the models adjusted for site were also nonsignificant (eTable 5 in Supplement 2). No significant differences were found between high- or low-intensity music therapy and standard care (eTable 6 in Supplement 2). Changes over time are shown in Figure 2. Prespecified subgroup analyses did not suggest different effects of music therapy vs standard care attributable to age (P = .30) or ASD subtype (P = .87).

Table 2. Observed Values and Changes From Baseline for Main Outcomesa.

| Observed Values | Change From Baseline | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Enhanced Standard Care | Improvisational Music Therapy | Enhanced Standard Care | Improvisational Music Therapy | |||||

| No. | Mean (95% CI) | No. | Mean (95% CI) | No. | Mean (95% CI) | No. | Mean (95% CI) | |

| ADOS Social Affectb | ||||||||

| Baseline | 182 | 13.49 (12.86 to 14.12) |

182 | 14.08 (13.43 to 14.73) |

||||

| 2 mo | 125 | 12.58 (11.81 to 13.34) |

145 | 13.88 (13.10 to 14.65) |

125 | −0.44 (−0.99 to 0.11) |

145 | −0.21 (−0.69 to 0.26) |

| 5 mo | 149 | 12.45 (11.71 to 13.19) |

165 | 13.27 (12.55 to 14.00) |

149 | −0.83 (−1.38 to −0.28) |

165 | −0.87 (−1.38 to −0.35) |

| 12 mo | 136 | 11.72 (10.95 to 12.49) |

154 | 12.60 (11.81 to 13.40) |

136 | −1.60 (−2.27 to −0.93) |

154 | −1.51 (−2.05 to −0.96) |

| SRS Totalc | ||||||||

| Baseline | 179 | 96.08 (91.76 to 100.41) |

180 | 96.03 (92.04 to 100.01) |

||||

| 2 mo | 120 | 93.73 (88.22 to 99.25) |

137 | 91.98 (87.53 to 96.42) |

119 | 0.33 (−3.04 to 3.70) |

135 | −2.52 (−5.25 to 0.21) |

| 5 mo | 129 | 93.29 (88.01 to 98.56) |

142 | 89.15 (84.61 to 93.70) |

128 | −1.97 (−5.60 to 1.66) |

141 | −5.23 (−8.44 to −2.03) |

| 12 mo | 126 | 88.64 (83.38 to 93.91) |

132 | 86.46 (81.20 to 91.72) |

124 | −5.06 (−8.94 to −1.19) |

131 | −7.37 (−10.95 to -3.78) |

Abbreviations: ADOS Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule; SRS, Social Responsiveness Scale.

Table reports observed values. Estimations from linear-effects models used for estimating effects are reported in eTables 5 and 6 in Supplement 2. The primary outcome (social affect values determined by linear mixed-effects models) are shown in Figure 2.

Range of possible scores, 0 to 27; higher scores indicate greater severity.

Range of possible scores, 0 to 195; higher scores indicate greater severity.

Figure 2. Effects of Interventions Over Time: Predicted Mean Values From Linear Mixed-Effects Models.

Graphs illustrate the predicted values from linear mixed-effects models presented in eTables 5 and 6 in Supplement 2. Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule (ADOS) social affect score (range of possible scores, 0-27; higher scores indicate greater severity; minimal clinically important difference, 1) over 5 months was the primary outcome. For the Social Responsiveness Scale (SRS) total, range of possible scores, 0 to 195; higher scores indicate greater severity. High-intensity music therapy comprised 3 music therapy sessions per week (up to 60 sessions); low-intensity music therapy comprised 1 music therapy session per week (up to 20 sessions).

Secondary Outcomes

Of 20 prespecified exploratory secondary outcomes, most showed no significant difference (eTables 5 and 6 in Supplement 2). ADOS social affect scores over 2 and 12 months and SRS total scores over 2, 5, and 12 months are also shown in Table 2 and Figure 2. Small but nominally significant effects were found in several SRS subscales (in linear mixed-effects models either adjusted or unadjusted for site)—music therapy was associated with greater improvements than standard care in social motivation over 5 months and autistic mannerisms over 2 and 12 months (eTable 5 in Supplement 2). In the 3-group comparison, low-intensity music therapy, compared with standard care, was associated with greater improvements in social awareness at 2 months; high-intensity music therapy, compared with standard care, was associated with greater improvements in autistic mannerisms over 5 months (eTable 6 in Supplement 2).

Exploratory Analyses and Outcomes

No significant difference between music therapy and standard care was seen in the sensitivity analysis using multiple imputation (mean difference, music therapy vs standard care, 0.06 [95% CI, −0.61 to 0.72]; P = .87) or including the music therapist as a random effect (mean difference, music therapy vs standard care, 0.05 [95% CI, −0.71 to 0.80]; P = .90).

Post hoc responder analyses indicated a higher proportion of improvement in ADOS social affect at 5 months in the music therapy group (95/182 [52%]) than in the standard care group (76/182 [42%]) (risk ratio, 1.25 [95% CI, 1.00 to 1.56]; risk difference, 0.10 [95% CI, 0.00 to 0.21], P = .047). The proportion of improvement was higher in participants who received at least 15 music therapy sessions (78/134 [58%]) than in those who received standard care (76/182 [42%]) (risk ratio, 1.39 [95% CI, 1.11 to 1.74]; risk difference, 0.16 [95% CI, 0.05 to 0.27]; P = .004).

Among the post hoc outcomes, mean changes in participants’ quality of life at 5 months were significantly more positive in the high-intensity music therapy group than in the standard care group, but no significant differences were seen in other outcomes or comparisons (eTables 5 and 6 in Supplement 2).

Adverse Events

Hospitalization or other institutional stay was rare at baseline (9 assigned to music therapy and 3 assigned to standard care had an institutional stay during the last 2 months). During participation in the study, these rates remained stable in the standard care group (3 at 2 months, 3 at 5 months, and 4 at 12 months) and decreased in the music therapy group (6 at 2 months, 6 at 5 months, and 4 at 12 months). These institutional stays were typically planned and short-term. No other adverse events or serious adverse events were reported.

Discussion

In this international, multicenter clinical trial of children with ASD, improvisational music therapy added to enhanced standard care, compared with enhanced standard care alone, resulted in no significant difference in symptom severity based on the ADOS social affect domain over 5 months. Additionally, the amount of improvement in both groups was small and less than the MCID, suggesting that use of improvisational music therapy for children with ASD may not lead to meaningful improvement in symptom severity and may not be warranted for improving autistic symptoms.

Most of the exploratory secondary outcomes were also nonsignificant. The few significant outcomes were small and unlikely to be clinically important. Observed differences in social responsiveness subscales may be artifacts attributable to multiplicity and lack of blinding. The post hoc finding of a higher proportion of responders in the music therapy group compared with the standard care group should be interpreted with caution and may be biased by differential attrition. No dose effect was found in the prespecified analyses.

The findings contrast with those of previous studies. A systematic review of 10 clinical trials concluded that music therapy may help children with ASD to improve skills in areas constituting the core of the condition. One important difference is that previous trials were limited to 1 local context and 1 or a few therapists, where consistent implementation of interventions may be easier than in a global trial.

Alternatively, methodological differences, such as the choice of a proximal vs a distal outcome, also may explain the difference. No trial of music therapy and very few trials of other psychosocial interventions showed effects on generalized behaviors using blinded assessments on the ADOS. Assessor-blinded trials of parent-mediated interventions have shown mixed results. A nonblinded study found effects of a teacher-directed intervention. Another nonblinded study of a developmental intervention, with more than 1000 treatment hours per child, did not.

Although a large number of treatment hours is considered important in autism interventions, early claims suggesting benefits with early intensive behavioral intervention were not replicated in rigorous randomized evaluations. The burden associated with attending therapy sessions also needs to be considered. In this study, participants assigned to music therapy tended to receive fewer other therapies, and not all were able to attend as frequently as planned, particularly when additional travel was needed.

Although the present trial did not capture the child’s experience with improvisational music therapy, it seemed very well accepted by parents, children, and staff. In a qualitative study connected to this trial, parents reported their children’s enjoyment and benefit from improvisational music therapy and experienced their own involvement as positive. This study represented a first attempt to implement music therapy consistently internationally, but more work is ongoing to improve it. This ranges from improving therapists’ ability to attune optimally to the child to including family members more actively.

Strengths and Limitations

The strengths of this study, compared with previous trials of music therapy in ASD, include its size, duration, blinding of the primary outcome, and multiplicity of perspectives.

However, several limitations must be noted. First, as a pragmatic trial, generalizability was higher, but music therapy was not as tightly controlled and perhaps not as consistently implemented as in previous single-center trials. Second, early termination may have affected the study’s ability to reliably detect an MCID, although the narrow confidence interval around the mean difference may ameliorate concerns about insufficient power.

Third, the duration of intervention and follow-up, although longer than in previous trials, may have been too short. In routine practice, music therapy for children with ASD is often continued for years rather than months. Delayed effects are not uncommon in ASD interventions. Fourth, the focus on symptom severity as an outcome, and the ADOS in particular, has been disputed. Some have argued for a shift toward outcomes such as well-being and adaptive functioning—being able to engage in learning, participate successfully in school through childhood and adolescence, and work and have meaningful relationships as adults—which may matter more to people with ASD than symptom severity. Fifth, all secondary outcomes were exploratory, nonblinded, and not adjusted for multiplicity.

Conclusions

Among children with autism spectrum disorder, improvisational music therapy, compared with enhanced standard care, resulted in no significant difference in symptom severity based on the ADOS social affect domain over 5 months. These findings do not support the use of improvisational music therapy for symptom reduction in children with autism spectrum disorder.

Study Protocol and Statistical Analysis Plan

eTable 1. Changes to the Study Protocol

eTable 2. Baseline Characteristics of Those Observed Versus Those Who Dropped Out at 5 Months

eFigure 1. Multidimensional Scaling of Baseline Characteristics by Treatment Group

eTable 3. Concomitant Treatments Provided as Part of Enhanced Standard Care

eTable 4. Mean Scores of Improvisational Music Therapy and Parent Counselling Principles

eFigure 2. Patterns of Improvisational Music Therapy Sessions Received Per Week

eFigure 3. ROC Curve for Optimal Treatment Fidelity Cutoffs

eTable 5. Linear Mixed-Effects Analyses—All Outcomes, Two Groups

eTable 6. Linear Mixed-Effects Analyses—All Outcomes, Three Groups

References

- 1.American Psychiatric Association Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5th ed Arlington, Va: American Psychiatric Publishing; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baxter AJ, Brugha TS, Erskine HE, Scheurer RW, Vos T, Scott JG. The epidemiology and global burden of autism spectrum disorders. Psychol Med. 2015;45(3):601-613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Buescher AV, Cidav Z, Knapp M, Mandell DS. Costs of autism spectrum disorders in the United Kingdom and the United States. JAMA Pediatr. 2014;168(8):721-728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Weitlauf AS, McPheeters ML, Peters B, et al. Therapies for Children With Autism Spectrum Disorder: Behavioral Interventions Update: Comparative Effectiveness Review No. 137. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2014. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wong C, Odom SL, Hume KA, et al. Evidence-based practices for children, youth, and young adults with autism spectrum disorder: a comprehensive review. J Autism Dev Disord. 2015;45(7):1951-1966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kanner L. Autistic disturbances of affective contact. Nerv Child. 1943;2:217-250. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Alvin J. Music Therapy for the Autistic Child. Oxford, United Kingdom: Oxford University Press; 1978. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stern DN. Forms of Vitality: Exploring Dynamic Experience in Psychology and the Arts. Oxford, United Kingdom: Oxford University Press; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Malloch S, Trevarthen C. Communicative Musicality. Oxford, United Kingdom: Oxford University Press; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Geretsegger M, Holck U, Carpente JA, Elefant C, Kim J, Gold C. Common characteristics of improvisational approaches in music therapy for children with autism spectrum disorder: developing treatment guidelines. J Music Ther. 2015;52(2):258-281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Certification Board for Music Therapists (CBMT) website. http://www.cbmt.org. Accessed May 30, 2017.

- 12.European Music Therapy Confederation (EMTC) website. http://www.emtc-eu.com/about-emtc. Accessed May 30, 2017.

- 13.Geretsegger M, Elefant C, Mössler KA, Gold C. Music therapy for people with autism spectrum disorder. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;6(6):CD004381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Geretsegger M, Holck U, Gold C. Randomised controlled trial of improvisational music therapy’s effectiveness for children with autism spectrum disorders (TIME-A): study protocol. BMC Pediatr. 2012;12(2):2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Geretsegger M, Holck U, Bieleninik Ł, Gold C. Feasibility of a trial on improvisational music therapy for children with autism spectrum disorder. J Music Ther. 2016;53(2):93-120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.World Health Organization International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems. 10th ed Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gotham K, Risi S, Pickles A, Lord C. The Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule: revised algorithms for improved diagnostic validity. J Autism Dev Disord. 2007;37(4):613-627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lord C, Rutter M, Le Couteur A. Autism Diagnostic Interview–Revised: a revised version of a diagnostic interview for caregivers of individuals with possible pervasive developmental disorders. J Autism Dev Disord. 1994;24(5):659-685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Constantino JN, Gruber CP. Social Responsiveness Scale (SRS). Los Angeles, CA: Western Psychological Services; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Aldred C, Green J, Adams C. A new social communication intervention for children with autism: pilot randomised controlled treatment study suggesting effectiveness. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2004;45(8):1420-1430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dawson G, Rogers S, Munson J, et al. Randomized, controlled trial of an intervention for toddlers with autism: the Early Start Denver Model. Pediatrics. 2010;125(1):e17-e23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Howlin P, Gordon RK, Pasco G, Wade A, Charman T. The effectiveness of Picture Exchange Communication System (PECS) training for teachers of children with autism: a pragmatic, group randomised controlled trial. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2007;48(5):473-481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pickles A, Le Couteur A, Leadbitter K, et al. Parent-mediated social communication therapy for young children with autism (PACT): long-term follow-up of a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2016;388(10059):2501-2509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Solomon R, Van Egeren LA, Mahoney G, Quon Huber MS, Zimmerman P. PLAY Project Home Consultation intervention program for young children with autism spectrum disorders: a randomized controlled trial. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 2014;35(8):475-485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Green J, Charman T, McConachie H, et al. ; PACT Consortium . Parent-mediated communication-focused treatment in children with autism (PACT): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2010;375(9732):2152-2160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gold C, Wigram T, Elefant C. Music therapy for autistic spectrum disorder. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006;(2):CD004381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.McGlothlin AE, Lewis RJ. Minimal clinically important difference: defining what really matters to patients. JAMA. 2014;312(13):1342-1343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Reichow B. Overview of meta-analyses on early intensive behavioral intervention for young children with autism spectrum disorders. J Autism Dev Disord. 2012;42(4):512-520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Blauth LK. Improving mental health in families with autistic children: benefits of using video feedback in parent counselling sessions offered alongside music therapy. Health Psychol Rep. 2017;5(2):138-150. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mössler K, Schmid W. What’s this adorable noise? relational qualities in music therapy with children with autism. Nord J Music Ther. 2016;25(suppl):51-51. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gottfried T, Thompson G, Carpente J, Gattino G. Music in everyday life by parents with their children with autism. Nord J Music Ther. 2016;25(suppl):89-90. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Silberman S. NeuroTribes: The Legacy of Autism and the Future of Neurodiversity. New York, NY: Penguin Random House LLC; 2015. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Study Protocol and Statistical Analysis Plan

eTable 1. Changes to the Study Protocol

eTable 2. Baseline Characteristics of Those Observed Versus Those Who Dropped Out at 5 Months

eFigure 1. Multidimensional Scaling of Baseline Characteristics by Treatment Group

eTable 3. Concomitant Treatments Provided as Part of Enhanced Standard Care

eTable 4. Mean Scores of Improvisational Music Therapy and Parent Counselling Principles

eFigure 2. Patterns of Improvisational Music Therapy Sessions Received Per Week

eFigure 3. ROC Curve for Optimal Treatment Fidelity Cutoffs

eTable 5. Linear Mixed-Effects Analyses—All Outcomes, Two Groups

eTable 6. Linear Mixed-Effects Analyses—All Outcomes, Three Groups