Abstract

This study examines the variability in color identification and perception of skin lesions in the context of background color and room illumination.

Color perception is a critical yet understudied component of diagnosing skin conditions in dermatology. In 2015, an image of a dress became a web viral event, instigating an immense debate as to whether it was black and blue or white and gold. Responses to this image showed the remarkable heterogeneity and individual variation in color perception, demonstrating that what each person sees does not necessarily match an objective reality.

Methods

This study was approved by the Boston University institutional review board. Oral informed consent was obtained from participants. A paper-based survey collected participant characteristics, and software (PowerPoint; Microsoft) was used to project a convenience sample of 10 skin lesions, cropped to a square shape to mask other morphologic and contextual characteristics (shape, size, body location). Each lesion was presented twice by simple randomization against a warm yellow and cool blue background (Figure), so that each participant coded 20 lesions. Correct color choice was independently agreed upon by 3 dermatologists and further confirmed by a color image extract tool, which provided the RGB (red, green, blue) decimal code color. Differences in mean scores stratified by participants’ demographic and baseline characteristics were compared using unpaired 2-tailed t test and 1-way analysis of variance. To allow each participant to serve as his/her own control and account for potential confounders, a matched analysis comparing rates of correct identification of each lesion color stratified by warm vs cool background was performed using McNemar test and Wilcoxon signed rank test.

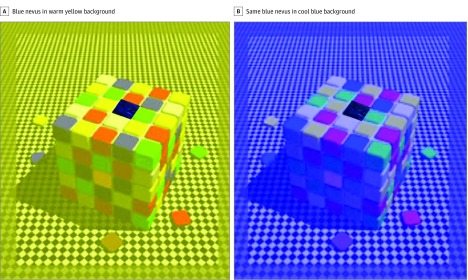

Figure. Blue Nevus on Warm Yellow and Cool Blue Backgrounds.

A, The left shows a cropped image of a blue nevus inserted in the center tile of a Rubik’s cube on a warm (yellow) background. B, The right shows the same cropped blue nevus on the center title of a cool (blue) background. Figures A and B were projected on different slides by simple randomization.

Background reproduced with permission of Lotto.

Results

Of 88 participants approached, 87 agreed to participate (Table). Group 1 (n = 45) responded to study questions in a dimly lit auditorium and group 2 (n = 40) in a clinic room with natural light. Overall, correct color identification irrespective of background color or illumination was mean (SD) 44.82% (8.96 ± 1.77). In the unmatched analysis, participants who answered the questions in a dimly lit room had a higher overall score (9.40 ± 1.64) when compared to those who answered the questions in a room lit with natural light (8.55 ± 1.84; P = .014). In the matched analysis, colors better identified on a cool background included lesions representing melanoma 95% (P < .001), nevus 87 % (P = .001), xanthoma 71% (P = .001), cherry angioma 71% (P = .018), and pseudomonas 55% (P = .028). Colors more accurately identified on a warm background included lesions representing port wine stain 32% (P < .001), blue nevus 84% (P < .001), lichen planus 92% (P = .022), pityriasis rosea 25% (P = .051), and lentigo 48% (P = .104).

Table. Basic Demographic Characteristic of 87 Study Participants.

| Characteristic | No. (%) | Overall Correct, Mean (SD) | P Valuea |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, y (n = 86) | .21 | ||

| 20-29 | 35 (40.70) | 9.51 (1.70) | |

| 30-39 | 31 (36.05) | 8.71 (1.74) | |

| 40-49 | 6 (6.98) | 8.67 (1.21) | |

| 50-64 | 12 (13.95) | 8.42 (2.07) | |

| ≥65 | 2 (2.33) | 8.00 (2.83) | |

| Sex (n = 87) | .11 | ||

| Male | 24 (27.59) | 8.58 (2.24) | |

| Female | 63 (72.41) | 9.11 (1.56) | |

| Race (n = 87) | .20 | ||

| White | 57 (65.52) | 9.00 (1.60) | |

| African American | 7 (8.05) | 7.86 (2.41) | |

| Asian | 23 (26.44) | 9.23 (1.93) | |

| Education (n = 86) | .01 | ||

| High school | 6 (6.98) | 8.83 (1.94) | |

| College | 20 (23.26) | 8.85 (1.73) | |

| Graduate school | 54 (62.79) | 9.30 (1.62) | |

| Other | 6 (6.98) | 6.38 (1.94) | |

| Occupation (n = 85) | .15 | ||

| Attending physician | 15 (17.65) | 8.87 (1.73) | |

| Medical trainee | 33 (38.82) | 9.45 (1.66) | |

| Other | 37 (43.53) | 8.65 (1.77) | |

| Years practicing dermatology (n = 24) | .35 | ||

| 1-5 | 10 (41.67) | 8.8 (0.92) | |

| 6-10 | 5 (20.83) | 9.4 (2.70) | |

| 11-20 | 1 (4.17) | 10.00 | |

| 21-30 | 4 (16.67) | 9.25 (0.96) | |

| ≥31 | 4 (16.67) | 7.25 (2.22) | |

| Vision (n = 86) | .28 | ||

| Corrected | 53 (61.63) | 8.89 (1.82) | |

| Normal | 33 (38.37) | 9.12 (1.75) | |

| Use of glasses (n = 80) | .41 | ||

| Yes | 52 (65) | 8.92 (1.82) | |

| No | 28 (35) | 8.82 (1.74) | |

| Visual problem (n = 87) | .56 | ||

| None | 39 (44.83) | 8.97 (1.75) | |

| Nearsighted | 32 (36.78) | 8.81 (1.79) | |

| Farsighted | 5 (5.75) | 9 (1.87) | |

| Astigmatism | 3 (3.45) | 10.67 (1.53) | |

| Mixed defect | 8 (9.20) | 8.88 (1.96) | |

| Color blindness (n = 81) | .79 | ||

| Yes | 1 (1.23) | 8.00 | |

| No | 78 (96.30) | 8.96 (1.80) | |

| Don’t know | 2 (2.47) | 9.50 (2.12) | |

| Dexterity (n = 85) | .35 | ||

| Right handed | 73 (85.88) | 9.08 (1.76) | |

| Left handed | 9 (10.59) | 8.67 (1.94) | |

| Ambidextrous | 3 (3.53) | 7.67 (2.08) | |

| Illumination (n = 85) | .01 | ||

| Dim light | 45 (52.94) | 9.40 (1.64) | |

| Natural light | 40 (47.06) | 8.55 (1.84) | |

| The dress (n = 87)b | .37 | ||

| White/gold | 48 (55.17) | 9.02 (1.80) | |

| Black/blue | 39 (44.83) | 8.90 (1.76) |

Where there is no SD in parentheses, the category contains a single observation with a single mean score and an SD of 0.

P values were generated either unpaired 2-tailed t test or one-way analysis of variance.

An image of a dress, a web viral event, instigating an immense debate as to whether it was black and blue or white and gold.

Discussion

This study highlights the heterogeneity of color perception, with 44.82% of lesion colors being correctly identified by participants. Color perception involves a complex interplay of physical properties of light, individual physiological responses, illumination, and background color. Color theories are quite complex with no consensus to date. For example, more correct identification of pink hues associated with lichen planus against the warm background can be explained by chromatic assimilation, a type of contrast in which the appearance of the stimulus is shifted toward the background color. However, more accurate identification of the purple of port-wine stain was made against a complementary background, which is thought to facilitate identification of colors on the opposite end of the color spectrum through factors that may increase saturation and brightness. Regarding illumination, participants in a dimly lit room had a higher overall score when compared to those in a room with natural light. Notably, we found no association of age, sex, underlying ophthalmologic conditions, and handedness with color perception.

The current study found that significant variability in color identification and perception exists, providing preliminary insight into the importance of background color and room illumination on correct color identification of skin lesions. Limitations include a small sample size, nonrandomized respondent population, and possible residual confounding. Larger studies are needed to further explore the impact of external factors on color perception when diagnosing skin lesions.

References

- 1.Moccia M, Lavorgna L, Lanzillo R, Brescia Morra V, Tedeschi G, Bonavita S. The Dress: Transforming a web viral event into a scientific survey. Mult Scler Relat Disord. 2016;7:41-46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brainard DH. Color constancy in the nearly natural image. 2. Achromatic loci. J Opt Soc Am A Opt Image Sci Vis. 1998;15(2):307-325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bompas A, Powell G, Sumner P. Systematic biases in adult color perception persist despite lifelong information sufficient to calibrate them. J Vis. 2013;13(1):19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brown RO, MacLeod DI. Color appearance depends on the variance of surround colors. Curr Biol. 1997;7(11):844-849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rosenholtz R, Nagy AL, Bell NR. The effect of background color on asymmetries in color search. J Vis. 2004;4(3):224-240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lotto RB, Purves D. An empirical explanation of color contrast. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97(23):12834-12839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]