This medical record review compares the incidence of cutaneous disease between white and nonwhite organ transplant recipients.

Key Points

Question

Should dermatologists evaluate organ transplant recipients differently based on race?

Findings

This medical record review of 412 organ transplant recipients found that the most common acute diagnosis for white recipients was malignant neoplasm compared with infectious or inflammatory conditions in nonwhite recipients, and most skin cancers in white and Asian recipients occurred in sun-exposed areas, whereas two-thirds of malignant neoplasms in black recipients occurred in sun-protected areas. Nonwhite organ transplant recipients were less likely to have regular dermatologic examinations and know the signs of skin cancer.

Meaning

Nonwhite organ transplant recipients need directed skin care in a transplant dermatology center with emphasis placed on race-associated risk factors.

Abstract

Importance

The risk for skin cancer has been well characterized in white organ transplant recipients (OTRs); however, most patients on the waiting list for organ transplant in the United States are nonwhite. Little is known about cutaneous disease and skin cancer risk in this OTR population.

Objective

To compare the incidence of cutaneous disease between white and nonwhite OTRs.

Design, Setting, and Participants

This retrospective review of medical records included 412 OTRs treated from November 1, 2011, through April 22, 2016, at an academic referral center. Prevalence and characteristics of cutaneous disease were compared in 154 white and 258 nonwhite (ie, Asian, Hispanic, and black) OTRs. Clinical factors of cutaneous disease and other common diagnoses assessed in OTRs included demographic characteristics, frequency and type of cancer, anatomical location, time course, sun exposure, risk awareness, and preventive behavior.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Primary diagnosis of malignant or premalignant, infectious, and inflammatory disease.

Results

The 412 patients undergoing analysis included 264 men (64.1%) and 148 women (35.9%), with a mean age of 60.1 years (range, 32.1-94.3 years). White OTRs more commonly had malignant disease at their first visit (82 [67.8%]), whereas nonwhite OTRs presented more commonly with infectious (63 [37.5%]) and inflammatory (82 [48.8%]) conditions. Skin cancer was diagnosed in 64 (41.6%) white OTRs and 15 (5.8%) nonwhite OTRs. Most lesions in white (294 of 370 [79.5%]) and Asian (5 of 6 [83.3%]) OTRs occurred in sun-exposed areas. Among black OTRs, 6 of 9 lesions (66.7%) occurred in sun-protected areas, specifically the genitals. Fewer nonwhite than white OTRs reported having regular dermatologic examinations (5 [11.4%] vs 8 [36.4%]) and knowing the signs of skin cancer (11 [25.0%] vs 10 [45.4%]).

Conclusions and Relevance

Early treatment of nonwhite OTRs should focus on inflammatory and infectious diseases. Sun protection should continue to be emphasized in white, Asian, and Hispanic OTRs. Black OTRs should be counseled to recognize the signs of genital human papillomavirus infection. Optimal posttransplant dermatologic care may be determined based on the race or ethnicity of the patients, but a baseline full-skin assessment should be performed in all patients. All nonwhite OTRs should be counseled more effectively on the signs of skin cancer, with focused discussion points contingent on skin type and race or ethnicity.

Introduction

The high incidence of cutaneous malignant neoplasms has been well described for patients who undergo solid organ transplant (organ transplant recipients [OTRs]) who are white. This risk is well known in the transplant community and correlates with intensity and duration of exposure to UV radiation and immunosuppression. Recent data indicate that mortality associated with skin cancer in OTRs may be even higher than that associated with breast or colon cancer after transplant.1 The establishment of specialty dermatology clinics for transplant recipients has been found to improve skin cancer awareness and protective behaviors, and such interventions are targeted at decreasing the burden of skin cancer in the population undergoing transplant.2

Despite these advances, little is known about the risk factors, incidence, locations, and types of skin disease that occur in nonwhite OTRs. Standardized models to efficiently address the dermatologic needs of nonwhite OTRs have not been implemented in our health care system, presumably owing to this lack of awareness. The US Census Bureau estimates that nonwhite, or minority, individuals will constitute most of the population by the year 2050.3 Correspondingly, 120 000 patients are on the waiting list for organs in the United States, 58% of whom are nonwhite individuals.4 This knowledge deficiency represents a significant practice gap within the field of transplantation. The aim of this study was to characterize the differences between nonwhite and white OTRs with regard to the nature of their risk for developing posttransplant skin disease and their attitudes and knowledge about these risks.

Methods

The Drexel Dermatology Center for Transplant Patients is a multidisciplinary medical-surgical dermatology center to which the Drexel University Abdominal Transplant Program refers all recipients of solid organ transplants for comprehensive skin examination. At present, referrals are made early in the patients’ posttransplant course. Patients undergo evaluation for all cutaneous lesions; suspicious lesions undergo biopsy, and those specimens with histologic findings suggestive of viral change are sent for human papillomavirus (HPV) typing. Patients are counseled on self-examination of the skin and photoprotection and receive written educational materials regarding skin cancer in OTRs. Questionnaires are administered to assess patients’ knowledge and behaviors toward skin cancer prevention. All patients are scheduled at least yearly for total body skin examination. This study was approved by the institutional review board of Drexel University. Informed consent was not required for this retrospective review of medical records.

A retrospective review of the medical records of 412 OTRs referred to the Drexel Dermatology Center for Transplant Patients from November 1, 2011, through April 22, 2016, was performed using the electronic medical record. First, we recorded a primary diagnosis, defined as the diagnosis of highest acuity, at the initial consultation, which included malignant or premalignant, infectious, and inflammatory categories. One hundred twenty-three patients failed to meet the criteria of having at least 1 of these 3 high-acuity conditions. Second, all skin cancers that were diagnosed after the date of transplant were reviewed for type and location. To investigate the risk associated with sun exposure, we divided body locations into 3 categories designated sun exposed (SE), sun protected (SP), and partially sun exposed (PSE). The SE category included the head, neck, scalp, and upper extremities. The SP category included the genitals, palms, fingertips, and finger webs. The PSE category included the lower extremities and trunk (chest, abdomen, and back). Third, questionnaires completed by OTRs presenting for their first visit were reviewed, with evaluation of the patients’ self-reported knowledge regarding skin cancer risk and prevention.

In each analysis, patients were stratified by race or ethnicity, including 154 white patients and 258 nonwhite (black, Asian, or Hispanic) patients. According to the US Census Bureau, individuals who identify as Hispanic, Latino, or Spanish may be of any race; thus, all Hispanic patients were grouped together, irrespective of race or ethnicity. Additional races (eg, Pacific Islander) represented by fewer than 5 patients were omitted from this analysis.

We created Kaplan-Meier survival curves representing cancer-free survival during the time from transplant to skin cancer diagnosis for 30 years after transplant. Patients lost to or unavailable for follow-up, those with nonskin cancer–related mortality, and those with inaccurate records were censored in the analysis. We used a log-rank test to determine the significance of the difference between white and nonwhite populations. Statistical analysis was not run on other comparisons owing to small sample size. All statistical analyses used SPSS Statistics software (SPSS Inc).

Results

Demographics

A total of 412 OTRs underwent evaluation during the study period. The study population included 154 white patients (37.4%) and 258 nonwhite patients (62.6%), of whom 190 (46.1%) were black, 35 (8.5%) were Asian, and 33 (8.0%) were Hispanic (Table). Most of the white OTRs self-identified Fitzpatrick skin types of I to III, whereas a predominant proportion of Asian, Hispanic, and black populations self-identified skin types of II to IV, III and IV, and V and VI, respectively. Two hundred sixty-four patients (64.1%) were male and 148 (35.9%) were female, with a mean age of 60.1 years (range, 32.1-94.3 years), and 292 (70.9%) had received a kidney transplant. The mean time from referral to the initial dermatology clinic visit was 64.5 days (range, 0-3023 days). The mean patient follow-up time from transplant was 2147.9 days (range, 16-8781 days). The mean time a patient was followed up in our clinic after the initial visit was 469.9 days (range, 4-1612 days). The mean time of immunosuppression ranged from 8.0 years (range, 0.1-29.8 years) in black patients to 11.9 years (range, 1.3-27.3 years) in Hispanic patients. The mean time from transplant to the diagnosis of first skin cancer was 6.57 years (range, 0.02-25.49 years).

Table. Demographic Characteristics of the Study Population.

| Characteristic | Racial or Ethnic Groupa | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All (N = 412) |

White (n = 154) |

Asian (n = 35) |

Hispanic (n = 33) |

Black (n = 190) |

|

| Age, mean (range), y | 60.1 (32.1-94.3) | 59.2 (32.1-93.8) | 58.2 (38.1-84.9) | 63.1 (35.3-92.0) | 60 (33.9-94.3) |

| Sex | |||||

| Male | 264 (64.1) | 114 (74.0) | 19 (54.3) | 22 (66.7) | 109 (57.4) |

| Female | 148 (35.9) | 40 (26.0) | 16 (45.7) | 11 (33.3) | 81 (42.6) |

| Organ transplant type | |||||

| Kidney | 292 (70.9) | 84 (54.5) | 28 (80.0) | 21 (63.6) | 159 (83.7) |

| Heart, lung, or both | 40 (9.7) | 25 (16.2) | 4 (11.4) | 1 (3.0) | 10 (5.3) |

| Liver | 48 (11.7) | 29 (18.8) | 3 (8.6) | 10 (30.3) | 6 (3.2) |

| Multiple organb | 32 (7.8) | 16 (10.4) | 0 | 1 (3.0) | 15 (7.9) |

| Duration of immunosuppression, mean (range), y | 9.2 (0.1-29.8) | 8.8 (0.1-29.8) | 8.2 (0.4-23.9) | 11.9 (1.3-27.3) | 8.0 (0.1-29.8) |

| Patients with skin cancer | 79 (19.2) | 64 (41.6) | 5 (14.3) | 4 (12.1) | 6 (3.2) |

| No. of lesions | 389 | 370 | 6 | 4 | 9 |

| BCC | 121 | 117 | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| SCC | 107 | 106 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| SCC in situ | 156 | 143 | 3 | 3 | 7 |

| Melanoma | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Other | 3 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Time to diagnosis of first lesion, mean (range), y | 6.57 (0.02-25.49) | 6.13 (0.02-25.49) | 3.75 (2.48-5.06) | 6.50 (1.53-14.51) | 12.67 (2.38-22.22) |

Abbreviations: BCC, basal cell carcinoma; SCC, squamous cell carcinoma.

Data are presented as number (percentage) of patients unless otherwise indicated. Percentages have been rounded and may not total 100.

Indicates kidney combined with pancreas, liver, lung, and/or heart.

Primary Diagnostic Category

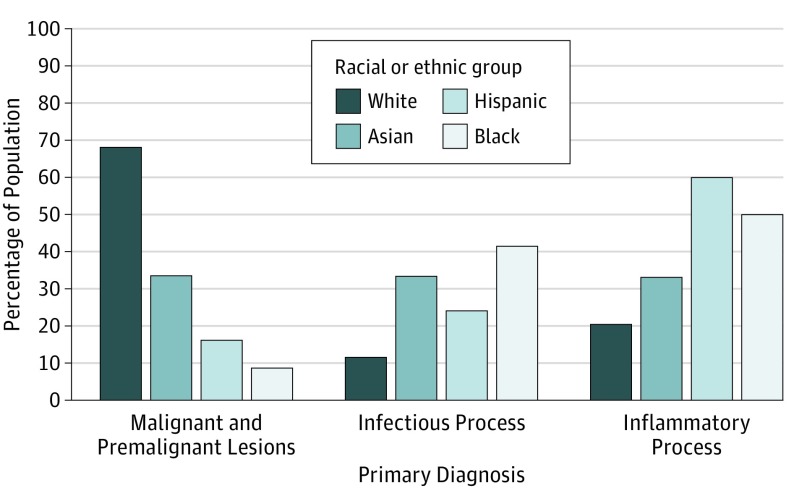

Two hundred eighty-nine OTRs exhibited malignant or premalignant, infectious, or inflammatory processes at the initial visit, including 121 white, 116 black, 25 Hispanic, and 27 Asian patients (Figure 1). In 82 white patients (67.8%), malignant or premalignant disease was the most common diagnostic category, with inflammatory and infectious processes among 25 (20.7%) and 14 (11.6%), respectively. Inflammatory processes (82 [48.8%]) and infectious processes (63 [37.5%]) were the most common diagnoses in nonwhite OTRs. Twenty-three nonwhite OTRs (13.7%) presented with malignant or premalignant lesions.

Figure 1. Primary Diagnosis by Race.

Incidence of malignant and premalignant lesions and infectious and inflammatory processes are depicted for white, black, Asian, and Hispanic organ transplant recipients.

Black and Hispanic OTRs were most often diagnosed with inflammatory (58 of 116 [50.0%] and 15 of 25 [60.0%], respectively) or infectious (48 of 116 [41.4%] and 6 of 25 [24.0%], respectively) conditions. Black and Hispanic patients rarely presented with malignant or premalignant conditions (10 [8.6%] and 4 [16.0%], respectively). The Asian population was evenly distributed at 9 patients (33.3%) each with malignant or premalignant, infectious, and inflammatory conditions.

Skin Cancer

A total of 389 skin cancers were diagnosed in 79 OTRs, with 370 (95.1%) lesions in white patients and 19 (4.9%) in nonwhite patients. Sixty-four of 154 white patients (41.6%) and 15 of 258 nonwhite patients (5.8%) developed skin cancer. Nine lesions were diagnosed in 6 black patients (3.2%), 4 lesions in 4 Hispanic patients (12.1%), and 6 lesions in 5 Asian patients (14.3%).

Overall, squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) in situ was the most common type of skin cancer diagnosed in each racial or ethnic group. We found 143 SCCs in situ, 106 SCCs, 117 basal cell carcinomas (BCCs), 2 malignant melanomas, 1 sebaceous carcinoma, and 1 trichilemmal carcinoma in the white cohort, with an SCC:BCC ratio of 2.13:1. In the nonwhite cohort, we found 13 SCCs in situ, 1 SCC, 4 BCCs, and 1 sebaceous carcinoma, for an SCC:BCC ratio of 4.5:1. No SCC was diagnosed in Hispanic or black OTRs.

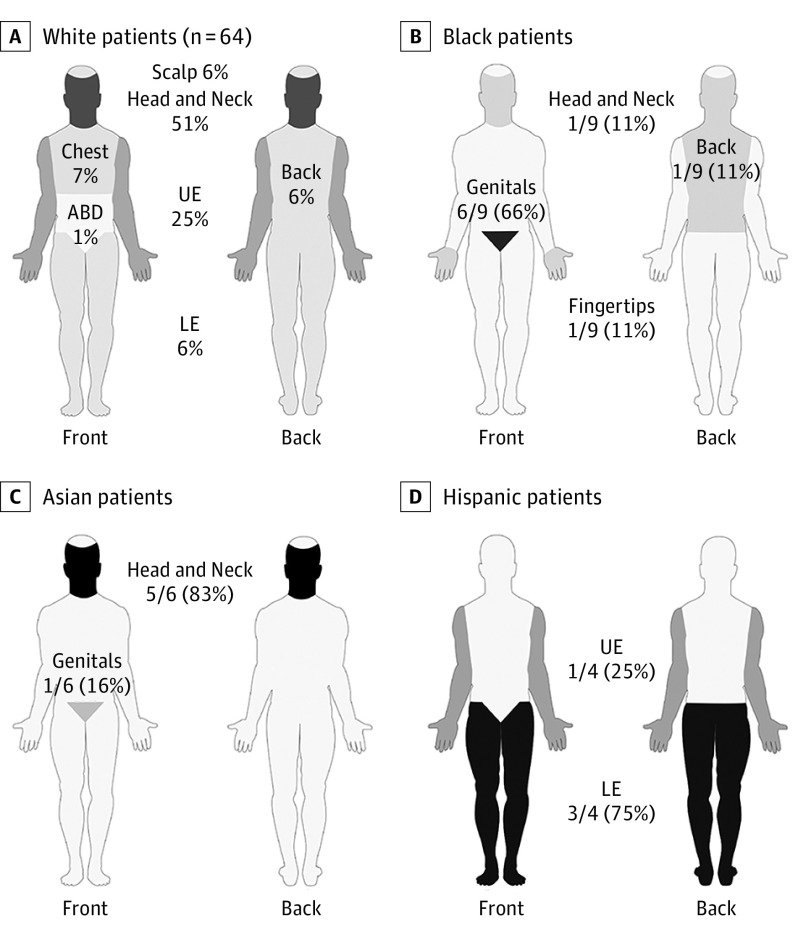

Most lesions in white (294 of 370 [79.5%]) and Asian (5 of 6 [83.3%]) OTRs occurred in SE areas (Figure 2). Three (75.0%) of 4 lesions in the Hispanic population occurred on PSE regions, with the remaining lesion found in an SE location. In the black population, 6 of 9 lesions (66.7%) occurred in SP areas, specifically the genitals. Four of 6 genital SCCs in situ had positive test results for high-risk HPV strains in 1 Asian and 3 black patients. Both lower extremity SCCs in situ found in 2 Hispanic OTRs had negative test results for HPV.

Figure 2. Anatomical Distribution of Cancer by Race.

Darkness of the shading directly correlates with the proportion of total lesions found in the respective location. Sun-exposed sites include the head, neck, scalp, and upper extremities (UE). Partially sun-exposed sites include the lower extremities (LE) and the trunk (chest, abdomen [ABD], and back). Sun-protected sites include the genitals, palms, fingertips, and finger webs.

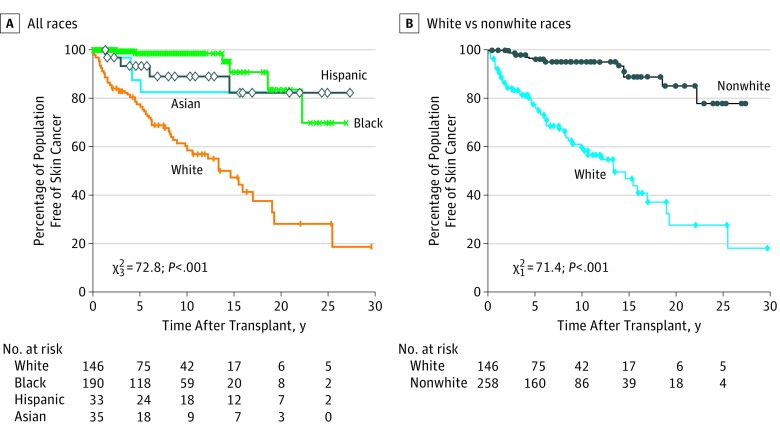

The mean time between transplant and diagnosis of a patient’s first skin cancer lesion was 6.13 years (range, 0.02-25.49 years) in white, 3.75 years (range, 2.48-5.06 years) in Asian, 6.50 years (range, 1.53-14.51 years) in Hispanic, and 12.67 years (range, 2.38-22.22 years) in black patients. At 5 years after transplant, 118 white (76.4%), 31 Asian (87.5%), 31 Hispanic (93.3%), and 187 black (98.6%) OTRs remained free of skin cancer. At 25 years after transplant, 29 white (18.8%), 29 Asian (82.6%), 27 Hispanic (82.2%), and 133 black (69.8%) OTRs remained free of skin cancer (χ23 = 72.8; P < .001) (Figure 3A). A log-rank test comparing white and nonwhite populations demonstrated a statistically significant difference between populations (χ21 = 71.4; P < .001) (Figure 3B).

Figure 3. Posttransplant Skin Cancer–Free Survival.

Kaplan-Meier curve of the percentage of the population without skin cancer as a function of time after transplant among white, Asian, Hispanic, and black organ transplant recipients and between white and nonwhite recipients.

Skin Cancer Risk Awareness and Prevention

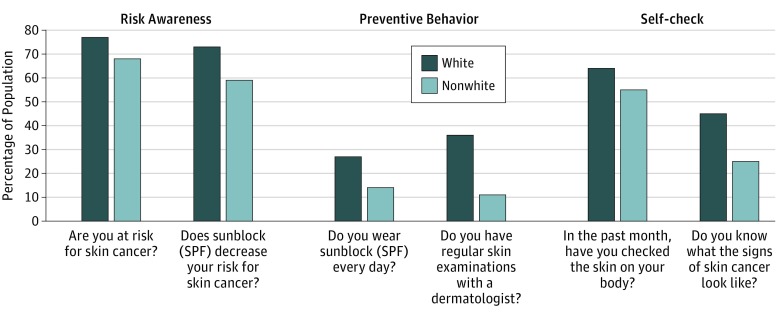

Sixty-six initial visit questionnaires were completed by 22 white, 35 black, 6 Hispanic, and 3 Asian patients (Figure 4). The patients were grouped into white and nonwhite owing to limited responses; follow-up with more patient responses may allow comparison among all 4 racial and ethnic groups. Seventeen white (77.3%) and 30 nonwhite (68.2%) OTRs were aware that their skin cancer risk was increased. Sixteen white (72.7%) and 26 nonwhite (59.1%) OTRs were aware that sunscreen decreased the risk for cancer. Six white (27.3%) and 6 nonwhite (13.6%) OTRs reported using daily sunscreen with a sun protection factor. Eight white (36.4%) and 5 nonwhite (11.4%) OTRs reported having regular dermatologic examinations.

Figure 4. Comparison of Skin Cancer Risk and Prevention by Race.

Patients’ awareness regarding their risk for skin cancer and the benefits of sunblock use, actions toward preventing skin cancer through use of daily sunblock and regular skin examinations, and knowledge and behavior for identifying possible skin cancer by themselves are compared between white and nonwhite organ transplant recipients. SPF indicates sun protection factor.

Fourteen white (63.6%) and 24 nonwhite (54.5%) patients reported having checked their skin during the previous month. Ten white (45.4%) and 11 nonwhite (25.0%) patients reported knowing the signs of skin cancer.

Discussion

This OTR cohort is unique because the population is derived from a multidisciplinary transplant dermatology model wherein all solid OTRs are referred for dermatologic evaluation. In addition, nearly two-thirds of the population consist of OTRs who identify as nonwhite, a group known to have distinct dermatologic needs.5

At presentation, 67.8% of white OTRs with an acute primary diagnosis had a malignant or a premalignant lesion. This finding explains the current cancer-centered approach to OTRs and argues for a continued concentration on malignant disease in these patients. However, analysis of nonwhite OTRs demonstrated contrasting patterns. In all nonwhite groups, most of the patients were diagnosed with an infectious or inflammatory process, whereas only 13.7% presented with malignant or premalignant lesions at the first visit. The true proportion of infectious and inflammatory conditions may be masked by the fact that patients with malignant or premalignant lesions may also exhibit inflammatory and infectious conditions.

Although early detection and treatment of cancer is vital, nonwhite OTRs would also benefit from addressing nonmalignant processes that are exacerbated by immunosuppression. Although infectious processes affect morbidity and mortality in OTRs, many banal conditions prove to be chronic with distinct burdens in these patients. The incidence of fungal and HPV infections is significantly increased in OTRs.6,7 The prevalence of viral warts in OTRs has been reported to be as high as 77% to 95% at 5 years after transplant, and beta-HPV may have a role in the formation of SCC.8,9,10 Organ transplant recipients with herpes simplex virus infection have more recurrent and severe symptoms than immunocompetent individuals, shed virus more frequently, and are at higher risk for developing disseminated infection.11,12,13 Furthermore, posttransplant dermatologic disease has been shown to significantly affect quality of life in OTRs, in particular dry skin, acne, genital warts, and herpes simplex virus type 1 infection.14 Studies suggest that skin cancer may have lesser effects on Dermatology Life Quality Index findings.14,15 Because quality-of-life issues influence choice of immunosuppressive agents, treatment protocols, and adherence with medication regimens, perhaps the lower incidence of malignant lesions in the immediate posttransplant period in nonwhite OTRs should not result in deferring evaluation but rather direct care toward more immediate quality-of-life interventions in these patients.

The most common type of skin cancer in our cohort was SCC. The ratio of SCC:BCC in OTRs has been reported to be approximately 3:1.16 In the present study, the ratio in white OTRs was 2.13:1, whereas in nonwhite OTRs it was 4.5:1. In addition, the prevalence and location of skin cancers differed among races and ethnicities. The white population developed skin cancer on SE sites. Results in nonwhite OTRs were variable, with the black population developing skin cancer on SP sites; Hispanic patients, on PSE sites; and Asian patients, on SE sites. These findings are consistent with what has been reported in the literature for their nonimmunosuppressed counterparts.17

The differences in prevalence and location observed in our cohort raise questions regarding risk factors. Despite the development of fewer lesions among Asian OTRs, the distribution of skin cancers in Asian OTRs parallels that of white OTRs, suggesting that sun exposure plays a significant role in the development of skin cancer in both subsets of patients.18,19 Hispanic and black OTRs developed more lesions in PSE and SP sites, respectively. The results of HPV typing in SCC in situ found in PSE and SP sites are consistent with reports suggesting a link between HPV and SCC.10 Our results also suggest a viral cause of SCC in SP locations, particularly in the black OTR population. Negative results of HPV typing in PSE lesions of Hispanic patients suggest that, despite developing lesions where an HPV-induced cause is suspected, sun exposure may be more significant in this population. Regardless, lesions in SP and PSE sites that are suggestive of verruca vulgaris or condyloma acuminatum among nonwhite OTRs should undergo biopsy, as should the lesions sent for HPV typing, in efforts to identify those at higher risk for developing cutaneous malignant disease. Furthermore, consideration should be given to routine administration of the HPV vaccine before transplant for all patients.

A total of 4 BCCs were diagnosed in our nonwhite OTRs, which were similar in anatomic location to those in white OTRs. UV radiation is a significant risk factor for BCC, and all lesions occurred on SE or PSE sites. In the black OTR cohort, 2 BCCs were found: one with a Pinkus tumor that was found 21 years after kidney transplant, and the other in a patient who underwent heart transplant with porphyria cutanea tarda 10 years after transplant. Both lesions underscore the limitations of focusing solely on sun-protective practices to decrease skin cancer risk in black OTRs.

In the United States, the risk for developing SCC increases with time after transplant, with a cumulative risk of 10% to 27% at 10 years and 40% to 60% at 20 years after transplant.16 In our study, statistically significant differences in disease-free survival were found between white and nonwhite populations. Cancer-free survival among white OTRs continually decreased after transplant, with 76.4% cancer free after 5 years but only 18.8% at 25 years. The Asian and Hispanic populations exhibited steady, moderate rates of decline, with 87.5% and 93.3% of the population free of skin cancer, respectively, after 5 years. The rate of decline stabilized thereafter, with 82.6% of Asian and 82.2% of Hispanic OTRs remaining cancer free after 25 years. At 5 years, 98.6% of black OTRs were cancer free, with a steep decrease occurring at 15 years after transplant that surpassed that of Asian and Hispanic OTRs within 10 years. At 25 years after transplant, 69.8% of black OTRs remained cancer free. This late decrease in cancer-free survival may be a manifestation of the small sample size and will benefit from follow-up monitoring as our patient population grows.

The results of our New Patient Visit survey revealed interesting trends. Most white and nonwhite OTRs reported that they are at risk for skin cancer. A predominant proportion of white and nonwhite patients reported knowing that sunblock decreases their risk for skin cancer and having checked their skin during the previous month. These findings were unexpected because other studies20,21 have described nonimmunocompromised nonwhite individuals as less likely to perceive themselves to be at risk for cutaneous malignant disease than their white counterparts. This discrepancy is likely explained by the emphasis that our Drexel University Abdominal Transplant Program places on the importance of dermatology as a part of comprehensive posttransplant care. Our nonwhite OTRs appear to be effectively counseled regarding the importance of skin cancer screening and routine dermatologic follow-up from an early stage.

Despite acknowledging their risk for skin cancer and modification strategies, our nonwhite OTRs were notably less likely to wear sunscreen and have skin checks with a dermatologist compared with our white OTR population. Our nonwhite cohort’s knowledge of the signs of skin cancer was significantly lower than that of their white counterparts. These results are consistent with reports of low use of sunscreen and rates of routine skin cancer screening in the nonwhite population.20,21 This finding emphasizes the need for development of routine, standardized, and focused education regarding prevention and signs of skin cancer for nonwhite OTRs.

Limitations

We acknowledge several important limitations to our study. The single-center retrospective design has inherent limitations. In addition, the sample size and follow-up periods were variable.

Conclusions

This study sought to characterize differences in posttransplant cutaneous disease between white and nonwhite OTRs. When compared with that among white OTRs, the incidence of skin cancer is significantly lower among nonwhite OTRs. Early management should focus on infectious and inflammatory cutaneous disease in efforts to improve quality of life and moderate skin cancer risk in nonwhite OTRs. Based on our findings, we suggest that optimal posttransplant dermatologic care be determined based on the race or ethnicity of the patients; however, regardless of skin type or race or ethnicity, a baseline full-skin assessment should be performed in all patients. Routine skin cancer follow-up screenings should be implemented immediately after transplant for Asian and Hispanic OTRs, particularly for those with Fitzpatrick skin types of II to IV and a history of increased sun exposure. Black OTRs may be able to delay yearly screenings; however, routine skin checks should begin earlier after transplant for all nonwhite OTRs, in particular black OTRs, with a history of or clinically evident HPV infection. With respect to cutaneous malignant disease, educational objectives for Asian and Hispanic OTRs should continue to focus on sun protection, which may be less pertinent for black OTRs. Black OTRs should be counseled to perform self-examination of the genitals and recognize the signs of HPV infection. All nonwhite OTRs should be counseled more effectively on the signs of skin cancer, with focused discussion points contingent on skin type and race or ethnicity.

References

- 1.Garrett GL, Lowenstein SE, Singer JP, He SY, Arron ST. Trends in skin cancer mortality after transplantation in the United States: 1987 to 2013. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;75(1):106-112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ismail F, Mitchell L, Casabonne D, et al. Specialist dermatology clinics for organ transplant recipients significantly improve compliance with photoprotection and levels of skin cancer awareness. Br J Dermatol. 2006;155(5):916-925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.US Census Bureau 2010. Census data. http://www.census.gov/2010census/data/. Accessed April 14, 2016.

- 4.US Department of Health and Human Services Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network; 2017. OPTN data. http://optn.transplant.hrsa.gov/data/view-data-reports/national-data/#. Accessed February 6, 2017.

- 5.Coley MK, Alexis AF. Managing common dermatoses in skin of color. Semin Cutan Med Surg. 2009;28(2):63-70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Alper S, Kilinc I, Duman S, et al. Skin diseases in Turkish renal transplant recipients. Int J Dermatol. 2005;44(11):939-941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Güleç AT, Demirbilek M, Seçkin D, et al. Superficial fungal infections in 102 renal transplant recipients: a case-control study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;49(2):187-192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Harwood CA, Perrett CM, Brown VL, Leigh IM, McGregor JM, Proby CM. Imiquimod cream 5% for recalcitrant cutaneous warts in immunosuppressed individuals. Br J Dermatol. 2005;152(1):122-129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Karagas MR, Nelson HH, Sehr P, et al. Human papillomavirus infection and incidence of squamous cell and basal cell carcinomas of the skin. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2006;98(6):389-395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Arron ST, Jennings L, Nindl I, et al. ; Viral Working Group of the International Transplant Skin Cancer Collaborative (ITSCC) & Skin Care in Organ Transplant Patients, Europe (SCOPE) . Viral oncogenesis and its role in nonmelanoma skin cancer. Br J Dermatol. 2011;164(6):1201-1213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Greenberg MS, Friedman H, Cohen SG, Oh SH, Laster L, Starr S. A comparative study of herpes simplex infections in renal transplant and leukemic patients. J Infect Dis. 1987;156(2):280-287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kusne S, Schwartz M, Breinig MK, et al. Herpes simplex virus hepatitis after solid organ transplantation in adults. J Infect Dis. 1991;163(5):1001-1007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Smyth RL, Higenbottam TW, Scott JP, et al. Herpes simplex virus infection in heart-lung transplant recipients. Transplantation. 1990;49(4):735-739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Moloney FJ, Keane S, O’Kelly P, Conlon PJ, Murphy GM. The impact of skin disease following renal transplantation on quality of life. Br J Dermatol. 2005;153(3):574-578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rhee JS, Matthews BA, Neuburg M, Smith TL, Burzynski M, Nattinger AB. Skin cancer and quality of life: assessment with the Dermatology Life Quality Index. Dermatol Surg. 2004;30(4, pt 1):525-529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zwald FO, Brown M. Skin cancer in solid organ transplant recipients: advances in therapy and management, I: epidemiology of skin cancer in solid organ transplant recipients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;65(2):253-261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gloster HM Jr, Neal K. Skin cancer in skin of color. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;55(5):741-760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Park GH, Chang SE, Won CH, et al. Incidence of primary skin cancer after organ transplantation: an 18-year single-center experience in Korea. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;70(3):465-472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chuang TY, Reizner GT, Elpern DJ, Stone JL, Farmer ER. Nonmelanoma skin cancer in Japanese ethnic Hawaiians in Kauai, Hawaii: an incidence report. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1995;33(3):422-426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ma F, Collado-Mesa F, Hu S, Kirsner RS. Skin cancer awareness and sun protection behaviors in white Hispanic and white non-Hispanic high school students in Miami, Florida. Arch Dermatol. 2007;143(8):983-988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Briley JJ Jr, Lynfield YL, Chavda K. Sunscreen use and usefulness in African-Americans. J Drugs Dermatol. 2007;6(1):19-22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]