Abstract

For the potential power of genome-wide association studies (GWAS) and translational medicine to be realized, the biomedical research community must adopt standard measures, vocabularies, and systems to establish an extensible biomedical cyberinfrastructure. Incorporating standard measures will greatly facilitate combining and comparing studies via meta-analysis, which is a means for deriving larger populations, needed for increased statistical power to detect less apparent and more complex associations (gene-environment interactions and polygenic gene-gene interactions). Incorporating consensus-based and well-established measures into various studies should reduce the variability across studies due to attributes of measurement, making findings across studies more comparable.

This article describes two consensus-based approaches to establishing standard measures and systems: PhenX (consensus measures for Phenotypes and eXposures), and the Open Geospatial Consortium (OGC). National Institutes of Health support for these efforts has produced the PhenX Toolkit, an assembled catalog of standard measures for use in GWAS and other large-scale genomic research efforts, and the RTI Spatial Impact Factor Database (SIFD), a comprehensive repository of georeferenced variables and extensive metadata that conforms to OGC standards. The need for coordinated development of cyberinfrastructure to support collaboration and data interoperability is clear, and we discuss standard protocols for ensuring data compatibility and interoperability. Adopting a cyberinfrastructure that includes standard measures, vocabularies, and open-source systems architecture will enhance the potential of future biomedical and translational research. Establishing and maintaining the cyberinfrastructure will require a fundamental change in the way researchers think about study design, collaboration, and data storage and analysis.

Background and Purpose

As the medical research community moves toward translational medicine—the “bench-to-bedside” philosophy—it is imperative to ensure that data are effectively shared among clinicians and across research studies. A cloud (or grid) computing cyberinfrastructure has been championed as an architecture that can effectively support this critical data -sharing activity. However, the hardware/software solution is in many ways easier to address than the revolution in thinking that will be required of researchers and clinicians, and integrating data will have limited value if the data were not collected using a comparable method and protocols. Achieving compatibility will require a paradigm shift away from protocols associated with a specific clinic or research environment to a national or global approach that will support the level of collaboration needed in contemporary medicine. Genome-wide association studies (GWAS) are a timely and compelling example demonstrating the need for standard (common) measures.1 Although recent GWAS reports have identified a large number of associations between chromosomal loci and complex human diseases, most studies have few measures in common. Standard measures will simplify the task of validating or combining GWAS. Over time, the use of standard measures will facilitate building larger populations for meta -analysis, thus providing increased statistical power and the ability to detect both more subtle and more complex associations.

The inclusion of common measures also can positively impact other study designs. Epidemiological and clinical studies will benefit greatly from including standard measures. Even if there is not a genetic component, it is now fairly common to collect and store biospecimens and add genomic data to studies at a later date. An increasingly important aspect of biomedical research receiving considerable attention is how to obtain high-quality measures of environmental exposures. In addition, the concept of environmental exposures has broadened to recognize not only physical and biological environmental exposures (e.g., smog, pathogens), but also social environmental exposures (e.g., social interactions, neighborhood safety).

Translational medicine depends on the coordination of clinical and research activities, especially through electronic medical records (EMRs) that all clinicians can use to record clinical information. An effective translational medicine research environment requires semantic interoperability among researchers and clinicians. To achieve semantic interoperability, the adoption of standard data formats and vocabularies is essential. There is a clear need to implement standard measures within EMRs, at least some of which are shared with the broader research community. There are many collaborative efforts:

electronic Medical Records and Genomics (eMERGE) Network (https://www.mc.vanderbilt.edu/);

PhenX (consensus measures for Phenotypes and eXposures; https://www.phenx.org/);

Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS), a series of centers to develop reliable and validated patient-reported outcomes (PROs) (http://www.nihpromis.org/default.aspx);

Grid-Enabled Measures (GEM) database for promoting standard measures tied to theoretically based constructs and sharing of harmonized data (http://cancercontrol.cancer.gov/brp/gem.html; see Moser et al. in this special supplement);

Genomics and Randomized Trials Network (GARNET), a GWAS of treatment response in randomized clinical trials that identifies genetic variants associated with response to treatments for conditions of clinical or public health significance (http://www.genome.gov/27541119/);

Gene Environment Association Studies (GENEVA) uses GWAS to find genetic risk factors in common conditions and assess their interplay with nongenetic risk factors ( http://www.genome.gov/27541319); and

Public Population Project in Genomics (P3G) fosters collaboration, optimizes design, promotes harmonization of biobanks, and facilitates transfer of knowledge (http://www.p3gobservatory.org).

All seek to find common ground among EMRs, GWAS, epidemiology, population, behavioral, and clinical studies. It is unrealistic to think that standard measures can be adopted in every case and across all research, clinical, and electronic environments. Thus, a corollary to the promotion of standard measures in the research and clinical environments is to develop effective methods for combining data acquired using similar, but not exactly the same, protocols—that is, data harmonization. The following section discusses two research efforts that could contribute to the development of an interoperable cyberinfrastructure.

Results

The PhenX Toolkit

PhenX has taken a consensus-based approach from 21 research domains to provide the research community with standard measures for GWAS and other large-scale genomic research efforts. First released in February 2009, the web-based Toolkit has been visited almost 200 times daily (148,372 visits as of December 10, 2010) and has nearly 400 registered users.2,3 Additionally, the National Human Genome Research Institute (NHGRI) and the National Institutes of Health’s (NIH’s) Office of Behavioral and Social Sciences Research (OBSSR) have provided an administrative supplement to encourage utilization of PhenX measures in relevant studies. The measures are selected by domain experts, using a consensus-based process, and are freely available to the scientific community in the PhenX Toolkit ( https://www.phenxtoolkit.org/). This is an example of a resource that clearly serves a need by providing measures that can serve as common currency for a variety of studies. The point is that to achieve data interoperability, an investment has to be made: significant changes will be seen only after the supporting resources are in place. The development of these types of resources is critical to motivating change across the scientific community.

The PhenX Toolkit includes a small number of measures (about 15) for each of 21 research domains. Each research domain is address by a working group of experts. The working groups must balance specific criteria set forth by the PhenX Steering Committee as they select measures for the Toolkit. The criteria for selection include well-established with demonstrated utility, low burden to participants and investigators, and are accessible to a wide range of investigators. The measures are intended to help researchers effectively expand a study beyond the primary research focus For example, a researcher planning a diabetes study may add PhenX measures from several domains (e.g., Ocular, Psychosocial) and also review (and include) measures from the Diabetes research domain. Detailed protocols are included to ensure that the measures (data) collected are comparable and remain valid. Visitors to the Toolkit can browse or search the resource, selecting measures of interest by adding them to a Cart. The Toolkit highlights additional essential measures that may be required to interpret results from a specific measure and also suggests additional related measures. After selecting the desired measures, users can request a Data Collection Worksheet, makes it easy for investigators to integrate PhenX measures into their study and ensures that relevant data are collected for each measure.

Examples of PhenX measures, exposures, risk factors, and questionnaires are shown in Table 1. Measures are phenotypes or exposures. Phenotypes may be disease outcomes (Angina, Depression), covariates (Height, Weight), or bioassays (Fasting Serum Insulin, Vitamin D). Exposures may be physical (Air Contaminants in the Home Environment, Ultraviolet Light Exposure), biological (HIV), behavioral (Alcohol—Lifetime Use, Caffeine Intake), or social (Social Support, Quality of Life). Some phenotypes and exposures may also be considered risk factors for various diseases and conditions.

Table 1.

Examples of PhenX Toolkit measures, domains, and protocol types

| Phenotypes | ||

|---|---|---|

| Measure name | Research domain | Protocol type |

| Current Age | Demographics | Interview-administered question |

| Height | Anthropometrics | Physical measurement |

| Fasting Serum Insulin | Diabetes | Bioassay |

| Angina | Cardiovascular | Interviewer-administered questionnaire |

| Exposures | ||

| Measure name | Research domain | Protocol type |

| Alcohol- Lifetime Use | Alcohol, Tobacco and Other Substances | Interviewer-administered questionnaire |

| Dust Collection- Vacuum Bag | Environmental Exposures | Self-administered sample collection with laboratory analysis |

| Social Support | Social Environments | Interviewer-administered questionnaire |

Source: https://www.phenxtoolkit.org/

Currently, PhenX maps to or creates Common Data Elements (CDEs; https://cdebrowser.nci.nih.gov/CDEBrowser/) to ensure compatibility with the cancer Biomedical Informatics Grid (caBIG);4,5 a similar process is used for Logical Observation Identifiers Names and Codes (LOINC) codes.6,7 Pilot projects exploring mapping PhenX measures to database of Genotypes and Phenotypes (dbGaP) and P3G variables have produced encouraging results.8,9

The RTI Spatial Impact Factor Database—A Geospatial Data Repository

The National Cancer Institute (NCI) of NIH has supported development of a comprehensive public-use database containing geospatial data describing physical and social environments over time (1960 to date) and place (multiple geographic levels). The RTI Spatial Impact Factor Database (SIFD) was developed to provide georeferenced data at various spatial scales with consistent geocoding, allowing researchers opportunities to choose the spatial scale most appropriate for their research question. Considerable resources were spent developing complex measures (e.g., residential segregation and Gini indices) to obviate the need for duplicative efforts by other researchers and to provide one source for all socioecological measures (http://rtispatialdata.rti.org/). Wide adoption of the SIFD would enhance data interoperability while also enhancing comparability of future studies. The estimated impacts of the geospatial variables on outcomes can be quite sensitive to nonstandard measures. When measures come from various sources using various algorithms or assumptions in data development and producing disparate measurement errors, then statistical noise clouds comparisons across studies. This noise can be reduced considerably by having a sole source for geospatial measures of socioecological factors. Establishing a reliable, fully documented, comprehensive resource freely available via the Web encourages use of the same geospatial data by all users, and as the emergent standard, the RTI SIFD can facilitate comparability across studies utilizing its measures. The SIFD is the most comprehensive set of multilevel geospatial data now freely available on the Web: it was downloaded more than 5,000 times in its first year online, showing potential to become the emergent standard.

Interoperability and Geospatial Analytic Cyberinfrastructure

Geospatial informatics tools and software have evolved over a long period characterized by many different platforms and products that could not exchange mapping information or data. Incompatibility issues hampered the widespread development and adoption of geospatial mapping and analysis software. Optimal use of informatics tools (e.g., geospatial sensors; tools for analyzing data) and resources (e.g., databases) depends on explicit understanding of concepts related to the data on which they compute. For geospatial analysis, the relevant standards are maintained by the Open Geospatial Consortium (OGC; http://www.opengeospatial.org/). OGC is a nonprofit, international, voluntary consensus standards organization that leads the development of standards for geospatial and location-based services. The OGC Standards and Specifications are technical documents freely available to the public that detail interfaces or encodings that informatics tools developers should adopt to build support for the interfaces or encodings to address specific interoperability challenges. The OGC Standards and Specifications define a service-oriented architecture for geographic applications that, when used during the phases of systems development by various enterprises, allows for eventual integration in computing. For example, when OGC Standards and Specifications are implemented by two different software engineers working independently, the resulting products work together without further reprogramming. OGC also provides compliance testing, and the Certified OGC Compliant brand assures customers that the products will interoperate with other systems that have properly implemented OGC standards. The Certified OGC Compliant brand also ensures that systems developers can integrate various products efficiently. The OGC standards have been an important contributing factor in the growth of the geospatial informatics tools market, and OGC compliance is increasingly necessary for market participants.

The RTI SIFD conforms with the standards set by this organization for all georeferencing codes (e.g., county codes used to link county data to county map files), the format for metadata, and in the open-source programming code used for mapping the data online via the Amazon cloud. Choosing database variables and mapping them on the Web with color coding of different value ranges for data is straightforward. However, users want the ability to map different variables quickly, change color or coding schemes, and to change spatial scales quickly (e.g., county vs. census tract). These geographic information system (GIS) functions require batches of multiple jobs to process. Cloud computing employs many servers simultaneously for faster results. Using Amazon’s cloud computing resources for mapping is a low-cost means to spread the workload over many servers for fast transitions between maps. OGC interoperability standards are necessary for using these resources with the SIFD.

The adoption of OGC Standards and Specifications has the potential to democratize the application of geospatial informatics tools across the globe. Capabilities exist to do cutting-edge visualization and mapping on the Web, as users can now upload their data and coordinates from a global positioning system (GPS) and do real-time mapping (see http://www.giscloud.com/). However, no informatics system is currently available to provide spatial analysis software in a format that allows users to perform advanced analysis on web -based or uploaded data. RTI and the GeoDa Center at Arizona State University are exploring the development of such a system for public use. This proposed spatial analytic cyberinfrastructure would serve the SIFD and spatial analytic software for analyzing it over the Web and use cloud computing to allow handing very large analyses. The proposed cyber-enabled system would be designed to be compatible with emerging biomedical cyberinfrastructure efforts such as caBIG and the Center for Disease Control and Prevention’s National Environmental Public Health Tracking System (http://www.cdc.gov/nceh/tracking/). A spatial analytic cyberinfrastructure compatible with the biomedical cyberinfrastructure has the potential to advance scientific knowledge and translational science, providing research leaders with new opportunities for team science. Uses include studies characterizing subjects in terms of their biological attributes, socioecological environments, and environmental exposure risks in their neighborhoods, allowing for uploaded GPS coordinates with field-collected data for real-time surveillance and planning.

Operational Systems and Ontology Standards for GWAS and Geospatial Systems

We have discussed two consensus-building systems—PhenX and OGC—along with a geospatial data repository, SIFD. To integrate any system or data project into the emerging cyberinfrastructure, investigators must understand and be willing to use operational standards. In addition, ontologies and standard vocabularies must be used to develop semantic and syntactic interoperability, allowing cyberinfrastructures to be built. One such operational biomedical cyberinfrastructure, caBIG, is in operation at NCI.4,5 Other databases, such as GEM, are built on the caBIG platform using the semantic and synantatic standards of caBIG. In a similar vein, PhenX is developing CDEs within the cancer Data Standards Repository (caDSR) to allow future harmonization and data sharing within the caBIG cyberinfrastructure.

To efficiently combine data, common definitions and common data values are needed so that anyone depositing or accessing data will use the same definitions (data dictionary) and data type (value). Unfortunately, as is often the case with emerging standards, there are many options in terms of ontologies and vocabulary servers at NIH. The NCI Thesaurus provides a single definition for every concept, whereas the National Library of Medicine’s Unified Medical Language System (UMLS) and the NCI Metathesaurus both provide mapping structures that connect similar concepts from many different sources.

NIH advocates that sharing data and tools across the biomedical research community adds tremendous value to the research enterprise and has supported several large infrastructure projects to allow data, standards, and tool sharing (e.g., caBIG, Biomedical Informatics Research Network [BIRN], PhenX, dbGaP], GENEVA, P3G, eMERGE, GARNET, PROMIS, GEM, and the NIH Toolbox). Recently, there has been much attention given to so-called service-oriented architecture for scientific applications—that is, standard design principles used during the phases of systems development for enhanced integration in computing. This attention has led to implementation of several collaborative interdisciplinary environments, such as the National Biomedical Computation Resource (http://www.nbcr.net/), the GeoSciences Network (http://www.geongrid.org/), the Science Environment for Ecological Knowledge (http://seek.ecoinformatics.org/), and the Community Cyberinfrastructure for Advanced Marine Microbial Ecology Research and Analysis (http://camera.calit2.net/).10

Table 2 presents an overview of the systems and vocabularies that can contribute to the development of a biomedical cyberinfrastructure.

Table 2.

Operational standards and vocabularies/ontologies

| Standard | Focus | Purpose | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| cancer Biomedical Informatics Grid (caBIG) | Cancer cyberinfrastructure | Integrate cancer research data and clinical trials | https://cabig.nci.nih.gov/ |

| Standard Vocabularies and Ontologies | |||

| Unified Medical Language System (UMLS) | Broad, biomedical | Classifications and coding to enable interoperability | http://www.nlm.nih.gov/research/umls/ |

| NCI Metathesaurus | Broad, biomedical | biomedical terminology database with a cancer focus | http://ncimeta.nci.nih.gov/ |

| NCI Thesaurus | Broad, biomedical | Biomedical ontology | http://ncit.nci.nih.gov/ |

Discussion

Common measures and operational standards are essential components of a cyberinformatics system that can effectively support data integration and analysis. The historical lessons presented by the competing development of computer operating systems (the demise of Tandy) and home video systems (Betamax vs. VCR) are examples of inefficient and duplicative development efforts. There will always be some competition between evolving standards; however, the evolution of open standards collectively selected by the scientific community may be an effective approach.2 Enhanced interoperability fosters efficient development of complementary products that attract users and increase market potential, enhancing the potential for widespread adoption.11

The critical need for a widely adopted cyberinfrastructure to support transdisciplinary research in biomedical sciences has been noted in a number of high -profile national reports.12,13 Similarly, Hesse has stressed the urgency of getting not only proteomics and genomics but also populomics—an emerging field focused on the potential role of technology and population health problems—into the cyberinfrastructure for public health.14–17 Hesse argues that cyberinfrastructure can affect population health in several ways: by expanding the scope of discovery through the use of new spatial pattern detection tools, by adding efficiencies to analysis and research design through visualization, by providing decision support for planning, by connecting many disparate sources of data, and by providing a basis for national and international planning. Eschenbach and Buetow argue that to achieve NCI’s ambitious goal of eliminating suffering and death due to cancer, a new generation of medicines is required, incorporating shared information technologies to connect and coordinate researchers across the cancer enterprise.4 Abrams and also Hesse and Shneiderman maintain that a cyberinfrastructure that joins biomedical research advances with the advances in cognitive and computational sciences can improve health care delivery systems and translate findings from bench to bedside and into policy.18,19

New eHealth solutions that permit integrative utilization of vast amounts of behavioral, biological, and community-level information will facilitate the analysis and interpretation of population-level data. This would enable the development of community-wide risk profiles that could form the foundation of a new populomics, which would be useful for reducing health disparities.14

Populomics research for translational science could become critically dependent on computing advances and informatics that allow linkage of data at multiple scales (personal, including genetic and biomolecular) and multiple levels of context; that use the data to implement advanced geovisualization, spatial, statistical, and multilevel modeling; and that engage the community in innovative ways to collect real -time georeferenced data and refine understanding of community dynamics.14,20,21 Research areas requiring these resources span behavioral science; demographic and social science; dynamic modeling of health, chronic disease, and disablement; environmental science; population biology; epidemiology; surveillance and comprehensive health planning; criminology; translational science; and many others.

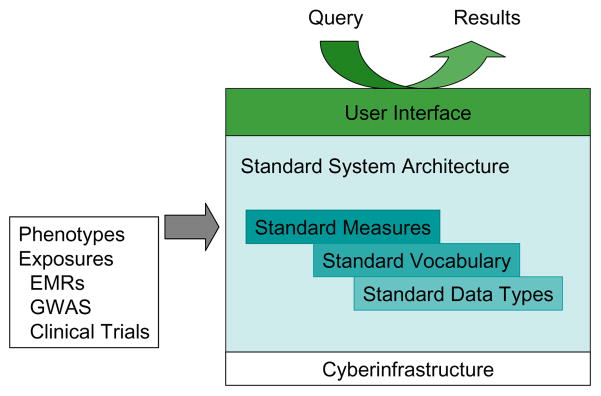

Realistically, a cyberinfrastructure that can support GWAS, translational research, and other interdisciplinary collaborations must embrace, extend, and connect existing resources. Consider dbGaP. Currently, NIH requires that any researchers who receive NIH funding to conduct a GWAS must deposit their data in dbGaP.8 However, dbGaP is not the only source of epidemiological study data. Some NIH institutes support independent data repositories (e.g., National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases [NIDDK]; National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute [NHLBI]), and some NIH institutes support registries (e.g., NCI). In fact, there are now so many registries that the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) has developed a Request for Applications (RFA) to establish a Registry of Patient Registries (AHRQ, DEcIDE ID Number 70 -EHC, ARRA: Developing a Registry of Registries). Another program that is building infrastructure is the Clinical and Translational Science Awards (CTSA; Institutional Clinical and Translational Science Award [U54], RFA Number RFA-RM-10-001). The CTSA program has led to improved integration of researchers and clinicians at major institutions, and more recent awardees have also been tasked with developing ways to connect these foci. For example, NHLBI has put out an RFA to develop a scalable tool for identifying common phenotypes (PFINDR: Phenotype Finder IN Data Resources: A Tool to Support Cross-study Data Discovery Among NHLBI Genomic Studies [UH2/UH3], RFA Number RFA-HL-11-020). Combining data from different studies is also complicated by privacy, security, and consent issues that are explored in other papers in this special supplement. Figure 1 illustrates how an integrated cyberinfrastructure could support a common web-based user interface, thus facilitating the identification of common data types across diverse data sources.

Figure 1.

Conceptual cyberinfrastructure

Notes: EMRs = electronic medical records; GWAS = genome-wide association studies.

Conclusion

The need to help investigators identify studies with similar or identical measures (common phenotypes) is clear, and it is also obvious that a paradigm shift is required. It is increasingly clear that studies will need to be combined and data shared in order to increase statistical power and significance. What is needed is a way to integrate public and private data resources and the development of publicly available tools for accessing all of this information. To achieve these goals will require some recognition and acceptance of standards, vocabularies, common measures, and the utilization of common data repositories. Although this may be a difficult path, it is critical to the future of biomedical research. Successful implementation will usher in a new era of interdisciplinary and collaborative research and translational research. This paper provides a road map to guide thinking about emerging systems and data standards that could serve as building blocks for a new biomedical cyberinfrastructure.

Footnotes

Publishable statement:

Dr. Schad has no commercial associations over the last 5 years that would propose a conflict of interest.

Dr. Mobley has no commercial associations over the last 5 years that would propose a conflict of interest.

Dr. Hamilton has no commercial associations over the last 5 years that would propose a conflict of interest.

Conflict of interest statement: Dr. Schad was supported by the Research Computing Division at RTI International and has no corporate or institutional affiliations other than RTI.

Dr. Mobley was supported as a Senior Fellow at RTI International for this work and has no corporate or institutional affiliations other than RTI.

Dr. Hamilton was supported by the Research Computing Division at RTI International and by National Human Genome Research Institute award U01 HG004597-01 and has no corporate or institutional affiliations other than RTI.

References

- 1.Pennisi E. Breakthrough of the year. Human genetic variation Science. 2007;318(5858):1842–3. doi: 10.1126/science.318.5858.1842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hamilton CM, Strader LC, Pratt JG, Maiese D, Hendershot T, Kwok R, et al. The PhenX Toolkit: Get the most from your measures. Am J Epidemiol. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwr193. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stover PJ, Harlan WR, Hammond JA, Hendershot T, Hamilton CM. PhenX:A toolkit for interdisciplinary genetics research. Curr Opin Lipidol. 2010;21(2):136–40. doi: 10.1097/MOL.0b013e3283377395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Eschenbach A, Buetow K. Cancer Informatics Vision:caBIG. Cancer Inform. 2007;2:22–4. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cimino JJ, Hayamizu TF, Bodenreider O, Davis B, Stafford GA, Ringwald M. The caBIG terminology review process. J Biomed Inform. 2009;42(3):571–80. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2008.12.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Forrey AW, McDonald CJ, DeMoor G, Huff SM, Leavelle D, Leland D, et al. Logical Observation Identifier Names and Codes (LOINC) database: A public use set of codes and names for electronic reporting of clinical laboratory test results. Clin Chem. 1996;42(1):81–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McDonald CJ, Huff SM, Suico JG, Hill G, Leavelle D, Aller R, et al. LOINC, a universal standard for identifying laboratory observations: A 5-year update. Clin Chem. 2003;49(4):624–33. doi: 10.1373/49.4.624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mailman MD, Feolo M, Jin Y, Kimura M, Tryka K, Bagoutdinov R, et al. The NCBI dbGaP database of genotypes and phenotypes. Nat Genet. 2007;39(10):1181–6. doi: 10.1038/ng1007-1181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Knoppers BM, Fortier I, Legault D, Burton P. The Public Population Project in Genomics (P3G): A proof of concept? Eur J Hum Genet. 2008;16(6):664–5. doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2008.55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Krishnan S, Bhatia K. SOAs for scientific applications: Experiences and challenges. Future Gener Comp Sy. 2009;15(4):466–73. doi: 10.1016/j.future.2008.09.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Scherer FM, Ross DR. Industrial market structure and economic performance. Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Atkins D, Droegemeier K, Feldman S, Garcia-Molina H, Klein M, Messeschmitt D, et al. Report of the National Science Foundation Blue-Ribbon Advisory Panel on Cyberinfrastructure. Washington, DC: National Science Foundation; 2003. Revolutionizing science and engineering through cyberinfrastructure. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Unsworth J, Courant P, Fraser S, Goodchild M, Hedstrom M, Henry C, et al. Report of the American Council of Learned Societies Commission on Cyberinfrastructure for the Humanities and Social Sciences. Washington, DC: American Council of Learned Societies; 2006. Our cultural commonwealth. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gibbons MC. Populomics. Stud Health Tech Inform. 2008;137:265–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hesse BW. Harnessing the power of an intelligent health environment in cancer control. Stud Health Technol Inform. 2005;118:159–76. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hesse BW. Public health informatics. In: Gibbons MC, editor. eHealth solutions for healthcare disparities. New York, NY: Springer; pp. 109–29. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hesse BW. Of mice and mentors: Developing cyberinfrastructure to support transdisciplinary scientific collaboration. Am J Prev Med. 2008;35(2 Suppl):S235–9. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2008.05.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Abrams DB. Applying transdisciplinary research strategies to understanding and eliminating health disparities. Health Educ Behav. 2006;33(4):515–31. doi: 10.1177/1090198106287732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hesse BW, Shneiderman B. eHealth research from the user’s perspective. Am J Prev Med. 2007;32(5 Suppl):S97–103. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2007.01.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gibbons MC, Brock M, Alberg AJ, Glass T, LaVeist TA, Baylin SB, et al. The Sociobiologic integrative model (SBIM) : Enhancing the integration of sociobehavioral, environmental, and biomolecular knowledge in urban health and disparities research. J Urban Health. 2007;84(2):198–211. doi: 10.1007/s11524-006-9141-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mabry PL, Olster DH, Morgan GD, Abrams DB. Interdisciplinarity and systems science to improve population health: A view from the NIH Office of Behavioral and Social Sciences Research. Am J Prev. 2008;35(2 Suppl):S211–24. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2008.05.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]