Abstract

Background

Even after negative sentinel lymph node biopsy (SLNB) for primary melanoma, patients who develop in-transit melanoma (ITM) or local recurrences (LR) may have subclinical regional lymph node involvement.

Study Design

A prospective database identified 33 patients with ITM/LR who underwent Tc-99m sulfur colloid lymphoscintography (LS) alone (n=15) or in conjunction with lymphazurin dye (n=18) administered only if the ITM/LR was concurrently excised.

Results

Seventy nine percent (26/33) of patients undergoing SLNB in this study had prior removal of LNs in the same lymph node basin as the expected drainage of the IT or LR at the time of diagnosis of their primary melanoma. LS at time of presentation with ITM/LR was successful in 94% (31/33) cases, and at least one SLN was found intraoperatively in 97% (30/31) cases. The SLNB was positive in 33% (10/30) of these cases. Completion LN dissection was performed in 90% (9/10) of cases. Nine patients with negative SLNB and ITM underwent regional chemotherapy. Patients in this study with a positive SLN at the time the IT/LR was mapped had a significantly shorter time to the development of distant metastatic disease compared to those with negative SLNs.

Conclusion

In this study, we demonstrate the technical feasibility and clinical utility of repeat SLNB for recurrent melanoma. Performing SLNB can not only optimize local, regional, and systemic treatment strategies for patients with LR or ITM but also appears to provide important prognostic information.

Keywords: in-transit melanoma, regional chemotherapy, sentinel lymph node biopsy

Introduction

Sentinel lymph node biopsy (SLNB) has a well-established role in the management of primary cutaneous melanoma while providing prognostic information in addition to a possible therapeutic benefit (1, 2). After initial appropriate management of the primary tumor, 2–10% of extremity melanomas will recur loco-regionally as local recurrences (LR) or in-transit disease (IT) (3, 4). Because of the concern that LR/IT may be accompanied by distant metastatic disease, the role of performing SLNB in the management of patients who develop LR/IT disease is less clear than in the case of primary tumors. However, a study from MD Anderson in the modern era of SLNB demonstrated that IT disease was the only site of recurrence in approximately 56% of patients (3).

Patients who develop unresectable LR or IT extremity disease and have no evidence of systemic metastases are often treated with regional chemotherapy (RC) in the form of hyperthermic isolated limb perfusion (HILP) or isolated limb infusion (ILI) with melphalan. RC achieves complete response rates of 30–55% with median duration of response ranging from 8 to 23 months (5–7). Notably, ILI does not treat the regional nodal basin as opposed to HILP which can include a regional node dissection as part of the process of placing vascular cannulas. The prevalence of regional node involvement in patients with IT/LR has been briefly explored with the use of SLNB (8, 9). In the largest report of SLNB performed in patients with IT/LR, 47% (14/30) of patients had a positive SLN (7), suggesting that ILI alone or HILP in the absence of an inguinal node dissection may be inadequate in nearly half the patients with IT disease. Therefore SLNB could be utilized to select appropriate modality of RC delivery in patients with IT or LR in addition to providing prognostic information and possibly a therapeutic benefit. Previous reports however are limited because they lacked specific methodology in these complex patients who often have multiple lesions and these studies do not include whether patients may have undergone SLNB or lymph node dissection at the time of primary melanoma diagnosis.

The technical aspects of performing SLN mapping of a primary melanoma are well described with success of identifying a SLN using vital blue dyes plus radiocolloid and intraoperative use of the hand held gamma probe approaching 99% (10). Performing SLNB in patients who develop IT or LR, many of whom have undergone previous LN biopsies or completion dissections may pose challenges not encountered when performing SLNB for primary melanoma. In a study from MD Anderson, independent predictors of IT recurrence after primary excision included Breslow depth, ulceration, and sentinel lymph node (SLN) status (3). Thus many patients with IT disease had intermediate or thick primaries and likely underwent SLNB (in the SLNB era) at the time of the primary diagnosis. Additionally, as suggested by the MD Anderson study, many patients who develop IT disease also had SLN involvement with the primary; these patients have historically been offered completion node dissection. As a result, the success rate of identifying the SLN in patients who have had previous LNs removed may be considerably lower. Additionally, there are no established criteria for determining which lesions to map in patients presenting with 2 or more IT lesions. The aims of this study are to 1) Describe our technique for performing SLNB in patients with LR or IT disease 2) Determine positivity rate of SLNB in a wider range of patients with IT disease and 3) Assess the clinical utility of performing SLNB in this patient population.

Methods

A prospective database identified 33 patients from 2005–2013 with locally recurrent or in-transit extremity melanoma undergoing SLNB. Local recurrences were defined as solitary lesions within 0.5 cm of the primary melanoma lesion or scar (Figure 1). Prior to SLNB, all patients had physical exam and whole body positron emission tomography/computed tomography (PET/CT) imaging. Any patient with distant metastatic disease or concern for regional node involvement on physical exam or PET/CT was not considered for SLNB. After therapy which included wide local excisions, SLNBs, lymph node dissections, or RC treatments, patients in this study were followed every three months for 1 year with physical exam and whole body PET/CT, every 6 months for 5 years and yearly thereafter to detect both local and distant metastases.

Figure 1.

A local recurrence (left). This single lesion is mapped using methods described plus vital blue dye as resection of the lesion is planned with SLNB. (Right) A patient with unresectable in-transit disease. The most proximal lesion (circled) is mapped using described methods and no blue dye is used.

The day prior to SLNB, patients underwent lymphoscintigraphy. When more than 1 IT lesion was present (Figure 1), the most proximal lesion was mapped by injecting 0.9 mCi to 1.0 mCi total of technetium Tc-99m sulfur colloid in four equal aliquots around the site of the tumor deposit. If multiple lesions were present at the same level, the largest lesion was mapped. Immediate images, three to four hour delayed images, and 23–24 hour delayed images were subsequently obtained (11). A hand held gamma probe was also utilized intraoperatively in all cases.

Once in the operating room, approximately 1–2 milliliters of isosulfan blue dye was injected into the lesion only if a resection of the mapped IT/LR was planned. For patients with 3 or fewer lesions and no single lesion greater than 5 cm (small volume disease), resection was usually performed at the time of SLNB (Figure 1). However, if the small volume disease was a second, rapid recurrence (less than 6 months), and the patient had not received any prior RC treatments, RC was planned and these patients did not get resection of their low volume disease at the time of SLNB. Lymph nodes were removed using similar guidelines for SLN removal for primary melanoma; all blue lymph nodes and all nodes that measuring 10% or higher of the ex vivo radioactive count of the hottest sentinel node were harvested (12). This study was approved by the Institutional Review Boards at Duke University and informed consent was obtained from all subjects.

Summary statistics were derived using established methods and presented as either percentages for categorical values or medians with ranges for continuous variables. A comparison of time to distant metastatic disease between those with a positive SLNB vs. negative SLNB was assessed with the log-rank test, and Kaplan-Meier curves were used display the results of these tests.

Results

The characteristics of patients’ (n=33) primary melanomas are listed in Table 1. The median thickness was 1.79 millimeters (n=23). There were eight upper extremity melanomas, two back melanomas and 23 lower extremity primary lesions. Twenty four (73%) of patients had undergone SLNB at the time of their primary melanoma diagnosis. One patient had also undergone resection of one regional lymph node at the time of primary diagnosis which was in 1994; the node was negative for malignancy but no imaging or dye techniques were used. Of the patients (n=24) who underwent SLNB of the primary melanoma, three had a positive lymph node in the inguinal nodal basin. Two of those patients underwent completion inguinal lymph node dissection while the remaining patient underwent systemic treatment. One additional patient had a negative inguinal SLNB at the time of primary diagnosis, developed IT disease, and was treated with ILI followed by HILP. Iliac (0/5) and obturator (0/5) lymph nodes removed during HILP were negative for malignancy. After achieving a complete response to HILP, this patient developed a single isolated extremity recurrence and underwent SLNB of the recurrence and thus is included in this study. In total, 26 of 33 (79%) of patients undergoing SLNB in this study had some prior removal of LNs in the same lymph node basin as the expected drainage of the IT or LR.

Table 1.

Primary Melanoma Characteristics

| Category | Data |

|---|---|

| Primary Tumor Breslow Depth | Median 1.79 mm [0.9–10.8], (N=23) |

| Previous SLNB | 73% (24/32) |

| Previous Positive SLNB | 13% (3/23) |

| Previous LN dissection | 9% (3/32) |

| Time to IT/LR | Median 25.7 months [7.7 m–16 years] (N=30) |

The median time to IT or LR was 25.7 months (Table 1) while 3 patients had melanoma of unknown primary. Four patients had LRs while 29 patients had IT extremity melanoma. Of the patients with five or fewer recurrent lesions (n=20), 18 had recurrent disease excised concurrently with planned SLNB while in 2 patients lesions were not resected because these patients were considered appropriate for regional chemotherapy treatments due to the rapid or repeat nature of the recurrences. We generally require candidates for regional chemotherapy at our institution to have clinically or radiologic measurable disease at the time of the procedure to determine the true efficacy of the treatment; as such even patients with low volume disease did not have resections if regional chemotherapy was planned. As discussed in methods, for the 22 patients who underwent resection of the recurrence, isosulfan blue dye was used in addition to lymphoscintigraphy to identify SLNs as outlined in Figure 2.

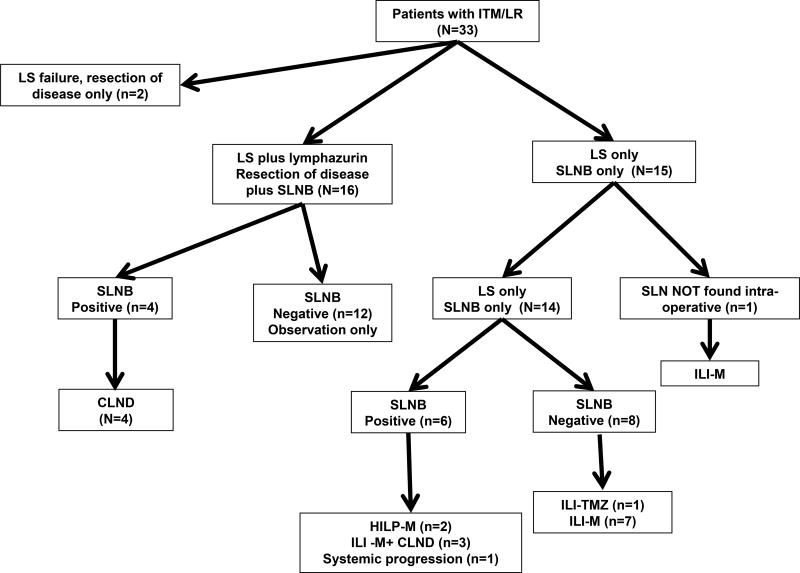

Figure 2.

Flow Diagram of Study Patients. Key: LS=lymphoscintography, ILI-M =isolated limb infusion melphalan, TMZ=temozolomide, HILP=hyperthermic isolated limb perfusion, CLND=completion lymph node dissection

Successful identification of at least 1 lymph node was visualized by imaging after lymphoscintigraphy (LS) in 94% (31/33) cases. Both failures were in patients who had undergone prior SLNB at the time of their primary melanoma. The first failure was in a local recurrence of a back melanoma, where LS identified more than eight 8 foci of activity in multiple anatomic sites; as such a decision was made not to perform a SLNB and resection only of the LR was carried out. The second failure was also in a patient with locally recurrent back melanoma and no nodes were identified on LS; as such excision only of the LR was performed. Notably, in the two patients with previous inguinal lymph node dissections, an iliac node was identified on imaging as the draining lymph node. Additionally a third patient who had 2/5 inguinal lymph nodes positive for melanoma during SLNB at the time of the primary melanoma but not did undergo completion nodal dissection also had an iliac node identified as the draining node. Finally, one patient with a primary melanoma on the distal arm underwent axillary SLNB at the time of the primary melanoma which was negative, and had antecubital (AC) fossa and axillary draining lymph nodes identified when the LR on the distal upper extremity was mapped.

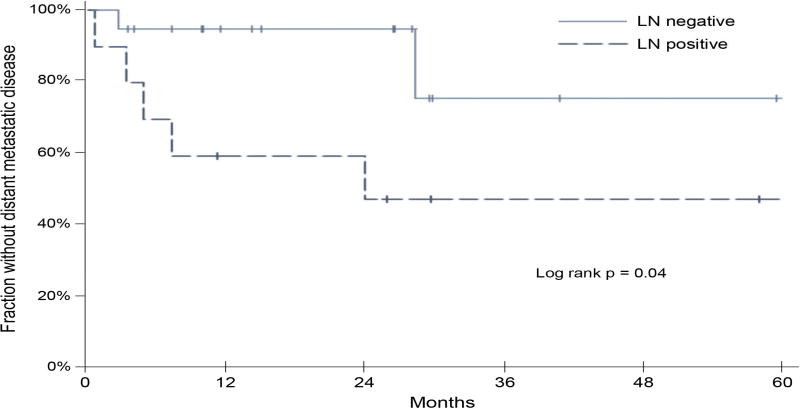

Ninety-seven percent (30/31) patients underwent removal of at least one blue or radioactive node. The procedure was well tolerated with no significant complications. One patient who had undergone a previous inguinal lymph node dissection had an iliac node identified on imaging but no lymph node was identified intra-operatively. Of 30 patients in whom a SLN was removed, 10 (33%) had evidence of metastatic melanoma involving the lymph node as outlined in Figure 2. Of the 3 patients with positive inguinal SLNBs at the time of primary melanoma, 2 patients had positive iliac nodes when the IT lesion was mapped and in 1 patient, the iliac node could not be found at the time of surgery. Three patients who did not have a SLNB at the time of primary diagnosis (n=1 melanoma unknown primary, n=2 SLNB not performed), had evidence of melanoma in the inguinal SLNB performed for IT disease. Finally, the remaining five patients who had positive SLNBs when the LR or IT lesion was mapped had negative SLNBs at the time of the primary melanoma. Patients in this study with a positive SLN at the time the IT/LR was mapped had a significantly shorter time to the development of distant metastatic disease compared to those with negative SLN as shown in Figure 3. Time to distant metastatic disease was calculated from the time of SLNB to development of any Stage IV disease (above the regional nodal basin).

Figure 3.

Kaplan Meier curve for time to development of distant metastatic disease for patients who were SLNB negative (green) and positive (orange).

After SLNB +/- excision of the IT or LR, patients fall into four categories as follows: 1) SLNB negative and all known extremity disease excised (n=12), 2) SLNB negative and extremity disease not excised (n=8 plus n=1 NO SLN found), 3) SLNB positive and all known extremity disease excised (n=4), and 4) SLNB positive and extremity disease not excised (n=6). Two of twelve patients in category one have developed extremity recurrences at six and eight months, respectively and subsequently underwent ILI. Eight patients in category 2 all underwent ILI with melphalan; three patients were complete responders (CR), one partial responder (PR), three patients had progressive extremity disease (PD), and one patient had PD after ILI with melphalan (ILI-M) but has been a complete responder (CR) to ILI with temozolomide (13).

All four patients in category 3 (SLNB +, extremity disease excised) underwent completion nodal dissections of the basin with the positive SLN. Two patients in Category 3 underwent inguinal node dissections with 0/7 and 0/3 lymph nodes positive for malignancy. One of these patients recurred in the extremity at 6 months, underwent ILI with no response, then underwent HILP during which 0/3 external iliac and 0/9 obturator nodes were found to be positive for malignancy. Two other patients in category 3 had 0/32 and 0/24 lymph nodes positive for malignancy at the time of axillary dissection. Finally, 6 patients were in category 4 (SLNB +, extremity disease not resected). Two patients subsequently had HILP during which 2/15 pelvic lymph nodes were found to be positive for melanoma and 0/13 nodes were found to be positive for melanoma in the other patient. Three patients underwent completion node dissection (1/7, 3/15, 3/8 lymph nodes positive for metastatic disease) plus ILI. One patient (positive iliac SLN) developed metastatic cutaneous disease outside the extremity and received systemic therapy with no additional surgery. In total, 9 of 10 patients with a positive SLN underwent completion dissection and 56% (4/9) had evidence of additional LN involvement.

Discussion

The role of SLNB in the management of locally recurrent or in-transit cutaneous melanoma is currently not well established. Here, we report a 33% (10/30) rate of SLN positivity in patients with IT/LR melanoma. Interestingly, patients (n=2) who had positive SLNB at the time of their primary melanoma also had positive SLNB at time of presentation with IT disease while five patients who were SLNB negative at the time of primary excision were SLNB positive at presentation with IT/LR. Whether these five represent initial false negatives or subsequent metastasis from the recurrent disease is unknown. The status of the SLN had important prognostic implications and helped guide optimal treatment strategies for all patients in this study.

Repeat SLN biopsy for recurrent breast cancer has been well studied (14). The false negative rate was 0.2% (14). The status of the repeat SLN biopsy results for these breast cancer patients (n=692) led to sparing of an axillary dissection in 213 patients and in 17.9% of patients the information led to a change in therapy (14). The status of the SLN in our melanoma population in this study was prognostic for the development of distant metastatic disease. We chose to compare time to development of distant metastatic disease instead of survival because long term follow up is not yet available. Time to distant metastatic disease is important as the 5 year survival for stage IIIC melanoma is around 40% while 5 year survival for Stage IV is 15–20% (15). In addition to prognostic information, the status of the SLN also served to help guide treatment strategies in patients who were candidates for regional chemotherapy treatments. ILI alone does not treat the regional nodal basin, thus patients with a positive SLN underwent ILI plus a lymph node dissection or HILP. Our data from over 200 regional chemotherapy treatments suggests a survival benefit for those obtaining a CR to regional chemotherapy; for ILI median survival was 39 months for CRs while for HILP, patients with CR had median survival of 100 months (5, 6). While treatments are generally well tolerated, there is a small risk (3–4%) of serious toxic limb side effects. Thus appropriate patient selection is critical. Given the likelihood for development of distant metastatic disease, patients with a positive SLN when the IT/LR is mapped should also be highly considered for systemic therapy. Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center is currently conducting a trial of systemic ipilimumab after ILI with melphalan and our group will be initiating a trial of neoadjuvant ipilimumab prior to ILI, both of which would be highly appropriate for patients with a positive SLN (16).

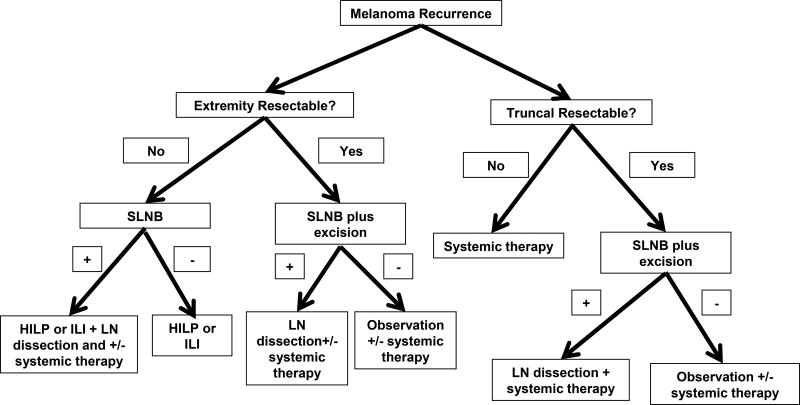

Importantly, the majority of patients in this study (78%) had some previous removal of lymph nodes in the expected drainage location of the IT/LR lesion. This is a reflection of the current era in which SLNB is routinely performed for appropriate primary melanomas. We found “redo” SLNB to be technically feasible in most situations. Ideally, “redo” SLNB is probably best performed at the first recurrence instead of after multiple recurrences and possible excisions. The selective use of blue dye also did not seem to affect our ability to recover the SLN. This is not necessarily surprising given that the use of LS alone without blue dye has been shown to be have a technical success rate of 98% (17). The few difficulties in this study were mainly in patients with prior formal LN dissections or who had a recurrence in an ambiguous region of drainage like the mid back. In the large metaanalysis of breast cancer patients undergoing repeat SLN biopsy for recurrent disease, sentinel node identification was successful in 81% of patients with no previous axillary dissection with a 52.2% success rate in patients who had prior axillary dissections (14). Thus for patients with previous LN dissections or ambiguous drainage patterns like the mid back, SLNB may still be considered but may be technically more challenging. We outline the following separate algorithms for patients with truncal melanoma recurrences and recurrent extremity disease in Figure 4. For patients with recurrent truncal melanoma that is not surgically resectable, SLNB is not recommended given the technical difficulty as well as the need for systemic therapy. Patients with resectable truncal disease can be considered for SLNB; if SLNB is positive, patients should undergo completion LN dissection plus systemic therapy, SLNB negative patients may need observation +/- systemic therapy. For any recurrent extremity disease, SLNB is recommended. Patients with unresectable extremity disease should undergo RC to include treatment of the lymph node basin (HILP or LN dissection) when the SLNB is positive. Patients with resectable extremity disease should also undergo SLNB biopsy, and completion dissection +/- systemic therapy should be considered for those who are SLN positive.

Figure 4.

Algorithm for use of SLNB in patients presenting with recurrent melanoma.

Our study is limited by a small number of heterogeneous patients. Certainly larger numbers and more long term follow up are needed. This is the first study to our knowledge to examine the use of SLNB in patients with LR/IT melanoma who also had SLNB at the time of primary melanoma diagnosis. Here, we demonstrate technical feasibility, SLN status to be a valuable prognostic factor, and assess how the SLN status can help guide treatment strategies. A SLNB at the time of development of IT/LR should be considered even if SLNB was performed at the time of primary diagnosis as in this study 33% (10/30) patients had evidence of metastatic disease in the SLN when the IT/LR was mapped including 5 patients who had a negative SLN at time of primary diagnosis.

Acknowledgments

Dr Salama is a paid consultant for Roche/Genetech and BMS and has a research grant from BMS. Dr Tyler is a paid advisory board member for Amgen, Gentech; a consultant for AGTC; a speaker for Novartis; receives royalties for a book chapter from Uptodate; and has a grant for a clinical trial from Schering.

This paper was supported in part by Duke University's T32 grant CA093245-10 from NIH (Beasley).

Footnotes

All other authors have nothing to disclose.

Presented at the Southern Surgical Association, 125th Annual Meeting, Hot Springs, Virginia, 2013. Also presented in part at the Society of Surgical Oncology’s (SSO’s) 65th annual Cancer Symposium, 2012 Washington, DC.

References

- 1.Morton DL, Thompson JF, Cochran AJ, et al. Sentinel-node biopsy or nodal observation in melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:1307–1317. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa060992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mark B, Faries MD, John F, Thompson MD, Cochran Alistair. The impact on morbidity and length of stay of early versus delayed complete lymphadenectomy in melanoma: results of the Multicenter Selective Lymphadenectomy Trial. Ann Surg Oncol. 2010 Dec;17(12):3324–3329. doi: 10.1245/s10434-010-1203-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pawlik TW, Ross MI, Johnson MM, et al. Predictors and natural history of in-transit melanoma after sentinel lymphadenectomy. Ann Surg Oncol. 2005;11:1612–61. doi: 10.1245/ASO.2005.05.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.van Poll D, Thompson JF, McKinnon JG, et al. A sentinel node biopsy procedure does not increase the incidence of in-transit recurrence in patients with primary melanoma. Ann Surg Oncol. doi: 10.1245/ASO.2005.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Raymond AK, Beasley GM, Broadwater G, et al. Current Trends in Regional Therapy for Melanoma: Lessons Learned from 225 Regional Chemotherapy Treatments between 1995 and 2010 at a Single Institution. J Am Coll Surg. 2011 Aug;213(2):306–16. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2011.03.013. Epub 2011 Apr 13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sharma K, Beasley GM, Turley R, et al. Patterns of recurrence following complete response to regional chemotherapy for in-transit melanoma. Ann Surg Onc. 2012;19:2563–2571. doi: 10.1245/s10434-012-2315-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kroon HM, Moncrieff M, Kam PCA. Outcomes Following Isolated Limb Infusion for Melanoma. A 14-year experience. Ann Surg Onc. 2008;15(11):3001–13. doi: 10.1245/s10434-008-9954-6. epub May, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yao KA, Hsueh EC, Essner R, et al. Is sentinel lymph node mapping indicated for isolated local and in-transit recurrent melanoma? Ann Surg. 2003;238:743–747. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000094440.50547.1d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Coventry BJ, Chatterton B, Whitehead F, et al. Sentinel lymph node dissection and lymphatic mapping for local subcutaneous recurrence in melanoma treatment: longer-term follow-up results. Ann Surg Oncol. 2004;11:203S–207S. doi: 10.1007/BF02523629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gershenwald JE, Tseng CH, Thomspon W, et al. Improved sentinel lymph node localization in patients with primary melanoma with the use of radiolabeled colloid. Surgery. 1998;124:203. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kalady MF, White DC, Fields RC, et al. Validation of delayed sentinel lymph node mapping for melanoma. Cancer J. 2001 Nov-Dec;7(6):503–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McMasters KM, Reintgen DS, Ross MI, et al. Sentinel lymph node biopsy for melanoma: how many radioactive nodes should be removed? Ann Surg Oncol. 2001 Apr;8(3):192–7. doi: 10.1007/s10434-001-0192-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Part of Multi-center Phase I trial of intra-arterial temozolomide for patients with advanced extremity melanoma, PI, Douglas Tyler, (unpublished results)

- 14.Maaskant-Braat AJG, Voogd AC, Roumen RMH, Nieuwenhuijzen GAP. Repeat sentinel node biopsy in patients with locally recurrent breast cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis of the literature. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2013;138:13–20. doi: 10.1007/s10549-013-2409-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Balch CM, Buzaid AC, Soong SJ, et al. Final version of the American Joint Committee on Cancer staging system for cutaneous melanoma. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19:3635–3648. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2001.19.16.3635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Personal communication Mary S. Brady, Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center.

- 17.Harlow SP, Krag DN, Ashikaga T, et al. Gamma probe guided biopsy of the sentinel node in malignant melanoma: a multicentre study. Melanoma Res. 2001 Feb;11(1):45–55. doi: 10.1097/00008390-200102000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]