Abstract.

Liposomal amphotericin B is being used increasingly to reduce the burden of kala-azar from the Indian subcontinent. There are studies which have evaluated efficacy and safety of liposomal amphotericin B for visceral leishmaniasis in all age groups. However, the only study that specifically addressed treatment of childhood visceral leishmaniasis did not include all ages or document renal and liver function. We, therefore, felt it was important to reassess the efficacy and safety of single dose liposomal amphotericin B in children and adolescents. A total of 100 parasitologically confirmed visceral leishmaniasis patients aged < 15 years were included in this study. Participants consisted of 65 males and 35 females. All of them had come from the endemic region of Bihar. They were administered one dose intravenous infusion of liposomal amphptericin B at 10 mg/kg body weight. Efficacy was assessed as initial and final cure at 1 and 6 months, respectively, and safety of all participants who were recruited in the study. The initial and final cure rate by per protocol analysis was 100% and 97.9%, respectively. Chills and rigors were the most commonly occurring adverse events (AEs). All the AEs were mild in intensity, and none of the patients experienced any serious AEs. No patients developed nephrotoxicity. Our finding indicates that liposomal amphotericin B at 10 mg/kg body weight is safe and effective in children. Results of our study support the use of single dose liposomal amphotericin B in all age group populations for elimination of kala-azar from the Indian subcontinent.

INTRODUCTION

Visceral Leishmaniasis (VL), also known as kala-azar, is a neglected tropical disease caused by the parasite Leishmania donovani in the Indian subcontinent. VL is transmitted by the bite of infected female phlebotomine sand flies. The disease is characterized by fever, hepatomegaly, splenomegaly, pancytopenia, weakness, and weight loss. More than 90% of global VL cases occur in Bangladesh, India, Nepal, Sudan, Ethiopia, and Brazil.1 It is highly endemic in the Indian state of Bihar, Jharkhand, West Bengal and Uttar Pradesh. In India, 40% of the VL patients are children.2 The disease commonly occurs among the poorest of the poor people belonging to the rural community. VL itself is a life threatening disease; its fatality is further intensified by coassociation with other emerging systemic disorders such as human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), tuberculosis, leprosy, etc. This has been identified as a major barrier in the control and elimination strategy of kala-azar from the Indian subcontinent. It is estimated that about 5–10% of successfully treated VL cases convert to post-kala-azar dermal leishmaniasis (PKDL) within 6 months to 2 years.3

There are limited drugs for the treatment of VL. Despite the life threatening toxicity of sodium antimony gluconate, it was the treatment of choice for VL over several decades. But because of its widespread resistance and treatment failure in the state of Bihar, its use has been restricted.4 Miltefosine is the only drug available orally for the treatment of VL but its efficacy is gradually decreasing over time.5 It is contraindicated in pregnant and lactating women and children less than 2 years of age owing to its teratogenic potential. Gastrointestinal side effects are the other limiting factor for routine clinical use. Paromomycin, an aminoglycoside antibiotic had shown high efficacy (cure rate 94.2%).6 However, it is associated with ototoxicity and nephrotoxicity. In addition, daily painful intramuscular injection for 21 days is the major demerit for its widespread use.

Amphotericin B deoxycholate is used in a dose of 1 mg/kg body weight daily or alternate days for 15–20 infusions.7 This drug is associated with numerous adverse drug reactions such as nephrotoxicity, hypokalemia, fever, and chills resulting in treatment discontinuation and noncompliance. The advancement of research in pharmaceutical formulation led to the discovery of a liposomal form of amphotericin B (AmBisome, Gilead). This modified form of amphotericin B specifically reaches the targeted organs such as liver, spleen, etc. and avoids exposure to other organs thereby minimizing the toxicity unlike conventional amphotericin B. A study with a single dose of AmBisome at 10 mg/kg IV has shown excellent result of safety and efficacy (cure rate of > 95%) in the Indian subcontinent.8

In the Indian subcontinent, studies were conducted with a single dose of AmBisome. However, no study was conducted exclusively in children and adolescents. A study in Bangladesh has successfully treated VL in mixed population, including children with a single dose of liposomal amphoterecin B. No significant difference was documented with regard to safety and efficacy in contrast to adults.9 The consensus among experts in Bihar is that 10 mg/kg single-dose first-line treatment should be prioritized for implementation in all endemic areas in India. Therefore, we aimed to assess the efficacy and safety of liposomal amphotericin B exclusively in children and adolescents.

METHODOLOGY

This prospective, single arm, open label study was conducted in a hospital setting at the Rajendra Memorial Research Institute of Medical Sciences (RMRIMS), a permanent institute of Indian Council of Medical Research (ICMR), Delhi, India, from February 2014 to November 2016. The institute serves as a tertiary level health care (referral center) in the state of Bihar, India. The study protocol was approved by the Scientific Advisory Committee and Institutional Ethics Committee of RMRIMS, Patna, and conducted in compliance with the protocol. Informed consent form was available in the local language (Hindi). Written informed consent was obtained from the legal guardians of all the participants as all the patients were minors.

Study procedure.

All the patients attended the outpatient department of RMRIMS with signs and symptoms suggestive for VL and had positive rK39 strip test. All were immediately admitted to the indoor setting. They were processed through splenic/bone marrow aspiration for parasitological confirmation. Patients with confirmed VL underwent biochemical and hematological investigations for baseline evaluation. All the eligible patients were treated as per the recommended guideline, that is single dose of Liposomal amphotericin B (AmBisome, Gilead Pharmaceuticals, Foster City, CA) at 10 mg/kg body weight, dissolved in 5% dextrose, administered by intravenous infusion over 2 hours. AmBisome was stored in a refrigerator at 2–8°C before administration. Patients were closely monitored (blood pressure, pulse rate, temperature, etc.) during infusion for adverse events (AEs). Patients were hospitalized for 7 days or longer, if severely ill or as per the investigator’s discretion. On discharge, all the patients were counseled properly to report any AEs they experienced. They were also advised to visit after 1 and 6 months for follow-up.

Inclusion criteria.

Participants of either sex, aged less than 15 years, and having clinical signs and symptoms consistent with kala-azar and positive rK39 test (Inbios) were included. The diagnosis was confirmed by parasitological analysis of splenic or bone marrow aspiration. Only parasitologically confirmed cases were included in the study.

Exclusion criteria.

Exclusion criteria were hemoglobin (Hb) < 5 g/100 mL; white blood cells count < 1,000/mm3; thrombocyte count < 50,000/mm3; alanine transaminase, aspartate transaminase, and alkaline phosphatase > 2.5 times upper limit of normal range; bilirubin ≥ 2 times upper limit of normal, serum creatinine or blood urea nitrogen ≥ 1.5 times upper limit of normal. Patients seropositive for HIV, hepatitis B and C, hypersensitivity to amphotericin B or inactive ingredients of the amphotericin B formulation were also excluded.

The rK39-negative patients were classified as non–kala-azar cases and managed by the treating physician for an alternative illness.

Safety assessment.

Patients were observed daily for the identification of AEs. They were subjected for hematological and biochemical tests, which included complete blood count, liver function test, serum urea and creatinine, serum electrolyte, etc. These tests were done at baseline, on the day of discharge and at 1 and 6 months follow-up. Grading of toxicity was done in accordance with the National Cancer Institute Common Terminology Criteria (NCI-CTC) AE, version 3.10

Efficacy assessment.

Efficacy was measured by initial cure at day 30 as absence of Leishmania donovani (LD) bodies (Grade 0 parasitic scores) in splenic or bone marrow aspirate smears and absence of fever or body temperature below 99°F, weight gain, improvement in hematological and biochemical parameters, and regression in spleen size compared with baseline values. Final cure was assessed at 6 months by complete regression of signs and symptoms of VL and absence of parasites in bone marrow/splenic aspirate smears. Treatment failure was defined as the nonimprovement in sign and symptoms of VL or relapse at any point during the follow-up period, which was confirmed by a positive bone marrow or splenic aspirate.

Rescue therapy.

Patients who were withdrawn from the study or relapsed at any point during follow up visit received rescue treatment with amphotericin B in the dose of 1 mg/kg body weight alternate days for 15 infusions in 5% dextrose slow intravenously.

Data analysis.

Data was analyzed by using SPSS software (version 16). Paired t test was applied for the comparison of mean before and after an intervention, and results were expressed as mean ± SD.

P value less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

A total of 113 VL patients were screened and 100 were eligible to be enrolled. The majority of patients (65%) were male, and half of the patients were between the age group of 4–10 years. Fourteen patients had a past history of VL for which they had been treated with different antileishmanial drugs (Table 1) and all of them had completed the full course of therapy.

Table 1.

Clinico-demographic characteristics of all the patients at the study enrollment

| Variables | Frequency (%) | Mean ± SD |

|---|---|---|

| Age | ||

| < 4 | 14 (14) | 1.9 ± 0.7 |

| 4–10 | 50 (50) | 7.3 ± 2.1 |

| > 10 | 36 (36) | 13.5 ± 1.3 |

| Sex | ||

| Male | 65 (65) | – |

| Female | 35 (35) | – |

| Symptoms* | ||

| Fever | 95 (33.8) | – |

| Anemia | 82 (29.1) | – |

| Hepatomegaly | 20 (7.1) | – |

| Splenomegaly | 51 (18.1) | – |

| Anorexia | 25 (8.8) | – |

| Cough | 7 (2.5) | – |

| Diarrhea | 1 (0.4) | – |

| Number of weeks ill before enrollment | ||

| ≤ 2 | 18 (18) | 1.88 ± 0.3 |

| 3–9 | 48 (48) | 5.64 ± 2.0 |

| ≥ 10 | 34 (34) | 14.6 ± 4.1 |

| Past History of VL | ||

| Yes | 14 (14) | – |

| No | 86 (86) | – |

| Past Treatment | ||

| SAG | 3 (21.4) | – |

| Miltefosine | 8 (57.1) | – |

| Amphotericin B | 3 (21.4) | – |

SD = standard deviation; – = not assessed.

One or more symptoms reported for each case.

At study enrollment, most of the cases presented with fever and anemia. Splenomegaly, hepatomegaly, anorexia, cough, and diarrhea were among the other symptoms. The average number of weeks the patients reported to have illness before study enrollment was 8.03, and 34% of cases had been ill for 10 weeks or longer. The detailed clinico-epidemiological characteristics of the patients at study enrollment are shown in (Table 1).

Efficacy.

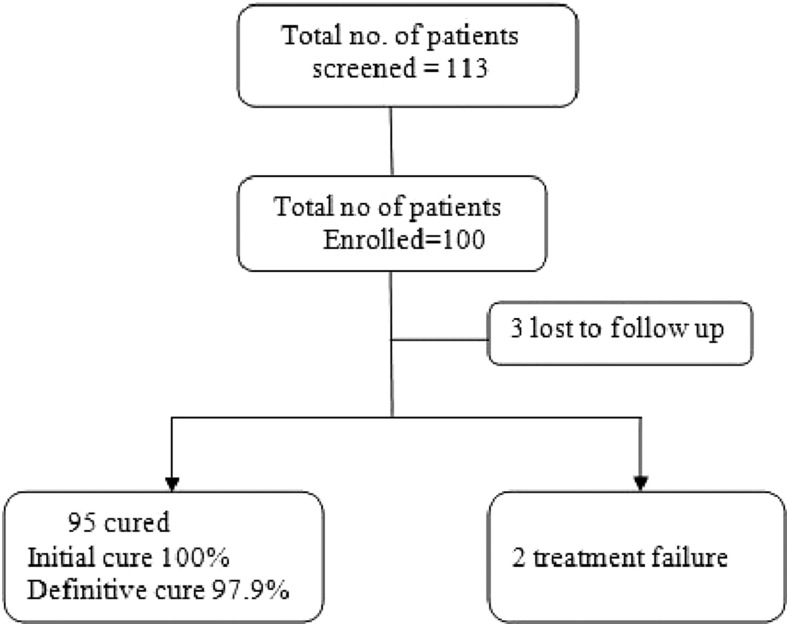

Posttreatment assessment was done at the 30 days follow-up visit. All the patients were afebrile with complete regression of spleen size. There was a remarkable improvement of hematological parameters and body weight at 1 and 6 month follow-up. The clinical parameters that indicate the treatment effectiveness are presented in (Table 2). Splenic/bone marrow aspiration revealed the absence of parasites in all the cases. Thus, the initial cure rate was 100%. Three patients did not turn up for the 6 months follow-up visit. Two patients relapsed at 4 and 6 months, respectively (Figure 1). Relapsed cases were characterized by recurrence of fever, splenomegaly, and worsening of biochemical and hematological parameters. Splenic aspiration from these patients demonstrated the presence of LD bodies. Definitive cure rate at 6 months by per protocol analysis was 97.9% [95% confidence interval: 92.7–99.4]. The relapsed cases were successfully treated with amphotericin B at 1 mg/kg body weight for 15 infusions in 5% dextrose on alternate days.

Table 2.

Hematological and biochemical parameters at the study enrollment, 30 day and 6 month follow-up

| Variable | Baseline mean (SD) | 30 day mean (SD) | 6 month | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline vs. 30 day | Baseline vs. 6 month | ||||

| Weight (kg) | 21.9 (10.1) | 23.76 (10.3) | 25.13 (10.4) | < 0.001 | < 0.001 |

| Spleen (cm below left costal margin) | 4.06 (3.6) | 0.55 (1.1) | 0.24 (0.54) | < 0.001 | < 0.001 |

| Hemoglobin (g/dL) | 7.0 (1.5) | 9.5 (1.3) | 10.1 (1.1) | < 0.001 | < 0.001 |

| Platelets (Lakhs/µL) | 1.24 (4.4) | 2.21 (7.8) | 2.86 (8.4) | < 0.001 | < 0.001 |

| White blood cells (/µL) | 3,833.0 (1,878.7) | 6,822.9 (1,967.8) | 7,561.9 (3,598.1) | < 0.001 | < 0.001 |

| Alanine aminotransferase ALT (U/L) | 47.9 (34.6) | 33.7 (9.5) | 31.8 (4.0) | < 0.001 | < 0.001 |

| Aspartate aminotransferase AST (U/L) | 61.7 (75.8) | 35.5 (8.3) | 31.1 (4.5) | 0.001 | < 0.001 |

| Creatinine (mg/dL) | 0.74 (0.16) | 0.74 (0.20) | 0.76 (0.1) | 0.924 | 0.225 |

| Urea (mg/dL) | 19.43 (3.2) | 19.87 (2.8) | 20.27 (2.2) | 0.004 | < 0.001 |

Figure 1.

Patients disposition.

Safety.

A total of 40 AEs were reported in the study. Chills and rigors were the most commonly occurring AEs followed by elevations of hepatic enzyme levels, abdominal pain, vomiting, etc. None of the patient developed nephrotoxicity, bleeding, or any serious AEs. All the AEs were mild in severity and resolved in RMRIMS without referral. Chills and rigors were experienced by 18 patients, but none of them discontinued the treatment and no drug intervention was required. The summary of AEs reported in the study is shown in (Table 3).

Table 3.

Summary of adverse events (AEs)

| Adverse events (N = 40) | Frequency (%) | CTC Grade |

|---|---|---|

| Gastrointestinal | ||

| Abdominal distension | 2 (5) | 1 |

| Abdominal pain | 4 (10) | 1 |

| Vomiting | 3 (7.5) | 1 |

| Elevation of hepatic enzymes (ALT/AST) | 8 (20) | 1 |

| Blood | ||

| Eosinophilia | 2 (5) | 2 |

| Infusion related reaction | ||

| Chills and Rigor | 18 (45) | 1 |

| Muscle-skeletal system | ||

| Back pain | 2 (5) | 1 |

| Others | ||

| Swelling of face | 1 (2.5) | 1 |

ALT = alanine aminotransferase; AST = aspartate aminotransferase.

DISCUSSION

Government of India targeted kala-azar elimination by 2017 with the goal to achieve kala-azar incidence less than 1 case/10,000 population at subdistrict [block primary health centers (PHCs)] level.11 The major strategies for kala-azar elimination under the national program are early diagnosis, complete treatment, and integrated vector management by indoor residual spray with synthetic pyrethroid. Owing to the effectiveness, ease of use, and assured compliance, the World Health Organization has recommended liposomal amphotericin B in a single dose of 10 mg/kg as the first line treatment in the Indian Subcontinent. Accordingly, it has been included in the program by the National Vector Borne Disease Control Program (NVBDCP).

Single dose liposomal amphotericin B (L-AmB) at 10 mg/kg body weight had showed promising efficacy (97.9%) and safety in children under this study. A similar result was also observed in Bangladesh among the mixed population of children and adults, stating that the single dose of AmBisome is safe and effective (cure rate 97%) in the treatment of VL.9 However, the report from Bangladesh was based solely on rK39 antigen test but, in this study, VL diagnosis was confirmed through parasitological assessment in splenic/bone marrow aspirates. Besides, we performed complete blood cell count and liver and kidney function tests at baseline, after treatment and at follow-up visits. These together generate strong evidence toward the efficacy and safety of single dose liposomal amphotericin B in children and adolescents. A prospective, open level study in children with two different dosage regimens of liposomal amphotericin B in the Mediterranean VL revealed that L-AmB at 10 mg/kg daily for 2 days produces greater therapeutic benefit without increasing toxicity in contrast to 4 mg/kg daily for 5 days.12 An open-label study by Sundar et al.7 tried conventional versus lipid formulations of amphotericin B (amphotericin B lipid complex and liposomal amphotericin B) in the treatment of VL and reported similar efficacy of all the formulations. However, with regard to safety, liposomal formulation (AmBisome) was found to have lower rates of toxicity in contrast to conventional amphotericin B deoxycholate or amphotericin B lipid complex.7

Currently, all the antileishmanial drugs are facing a growing crisis of drug resistance, hence interest to find out the combination therapy are increasing day by day among researchers and scientists. L-AmB had also been successfully tried in combination with miltefosine and paromomycin. A randomized controlled study of a single dose liposomal amphotericin B at 3.75–5 mg/kg followed by oral miltefosine for 7, 10, or 14 days reported that the efficacy is almost similar in all groups (cure rate 96% or higher).13 Similarly, single injection of 5 mg/kg liposomal amphotericin B was combined with single 10-day 11 mg/kg intramuscular paromomycin demonstrated high cure rate (97.5%).14

The therapeutic outcome for VL is not satisfactory; moreover, available treatment options for childhood VL are prohibited by many factors. Miltefosine, which is used orally for VL, is contraindicated in children below 2 years of age, in addition to its gastrointestinal side effects; children may face difficulty in swallowing the capsules. Conventional amphotericin B deoxycholate, although consistently showing high efficacy in VL, nephrotoxicity and hypokalemia are major problems associated with it. Prolonged hospitalization and close monitoring of patients are also required for this regimen. Paromomycin is another treatment choice found to be effective in VL but its efficacy in children is yet to be established.15 Considering all these treatment difficulties liposomal amphotericin B (AmBisome) remains the only option left for the treatment of childhood VL. AmBisome besides being less toxic and highly effective carries several other advantages in terms of better compliance (owing to single dose administration), reduced period of hospitalization, suitability for pregnant women and children,16 and is feasible to be administered at rural hospitals.9 In addition, it had a lower conversion rate to PKDL, which is considered as a reservoir of parasites. The major limitations are affordability and instability at high temperature (cold chain is needed). As VL affects poorest of poor people, cost effectiveness was a major barrier to get access to this therapy earlier. Since 2007, Gilead has reduced the price of AmBisome for all VL affected low- and middle-income countries, and at present it is being provided free of cost by the Government of India/NVBDCP at PHCs and Sadar hospitals as well as at tertiary level facilities.

Safety and tolerability profile of single dose AmBisome was found excellent. Although the majority of AEs had a definite relationship with the study drug, all the AEs were mild in intensity. Chills and rigors were the most commonly occurring drug related AEs. The hepatic enzymes level was mildly elevated in 8% patients. We did not find elevated serum creatinine or renal impairment in any patient, which is in concordance with the previous studies.17–19 This indicates that nephortoxicity is rarely occurring with AmBisome. These findings were consistent with other studies where common AEs reported with different doses of liposomal amphotericin B were chills, rigors, nausea, vomiting, and back pain.20–22

In conclusion, single dose liposomal amphotericin B at 10 mg/kg was found to be safe and effective in children. Therefore, continued use of this drug in the treatment of VL in all age groups is recommended and is of great value in the Kala-azar Elimination Program.

Acknowledgments:

We are highly indebted to Sanjay Kumar Chaturvedi and Mr Naresh Kumar Sinha for their technical support.

REFERENCES

- 1.Alvar J, Vélez ID, Bern C, Herrero M, Desjeux P, Cano J, Jannin J, den Boer M, 2012. Leishmaniasis worldwide and global estimates of its incidence. PLoS One 7: e35671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sundar S, Chatterjee M, 2006. Visceral leishmaniasis—current therapeutic modalities. Indian J Med Res 123: 345–352. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zijlstra EE, Musa AM, Khalil EA, el-Hassan IM, el-Hassan AM, 2003. Post-kala-azar dermal leishmaniasis. Lancet Infect Dis 3: 87–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Thakur CP, Narayan S, Ranjan A, 2004. Epidemiological, clinical and pharmacological study of antimony-resistant visceral leishmaniasis in Bihar, India. Indian J Med Res 120: 166–172. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sundar S, Singh A, Rai M, Prajapati VK, Singh AK, Ostyn B, Boelaert M, Dujardin JC, Chakravarty J, 2012. Efficacy of miltefosine in the treatment of visceral leishmaniasis in India after a decade of use. Clin Infect Dis 55: 543–550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jamil KM, et al. 2015. Effectiveness study of paromomycin IM injection (PMIM) for the treatment of visceral leishmaniasis (VL) in Bangladesh. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 9: e0004118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sundar S, Mehta H, Suresh AV, Singh SP, Rai M, Murray HW, 2004. Amphotericin B treatment for Indian visceral leishmaniasis: conventional versus lipid formulations. Clin Infect Dis 38: 377–383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sundar S, Chakravarty J, Agarwal D, Rai M, Murray HW, 2010. Single-dose liposomal amphotericin B for visceral leishmaniasis in India. N Engl J Med 362: 504–512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mondal D, Alvar J, Hasnain MG, Hossain MS, Ghosh D, Huda MM, Nabi SG, Sundar S, Matlashewski G, Arana B, 2014. Efficacy and safety of single-dose liposomal amphotericin B for visceral leishmaniasis in a rural public hospital in Bangladesh: a feasibility study. Lancet Glob Health 2: e51–e57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.National Cancer Institute Cancer Therapy Evaluation Program, Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events, Version 3.0 DCTD, NCI, NIH, DHHS. 2006. Available at: http://ctep.cancer.gov. Accessed February 2, 2016.

- 11.Health Ministers Committed to Eliminate Kala-azar (media advisory), 2014. New Delhi: WHO Regional Office for South-East Asia. Available at: http://www.searo.who.int/mediacentre/releases/2014/pr1580/en/.

- 12.Syriopoulou V, Daikos GL, Theodoridou M, Pavlopoulou I, Manolaki AG, Sereti E, Karamboula A, Papathanasiou D, Xenophon KGS, 2003. Two doses of a lipid formulation of amphotericin B for the treatment of mediterranean visceral leishmaniasis. Clin Infect Dis 36: 560–566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sundar S, Rai M, Chakravarty J, Agarwal D, Agrawal N, Vaillant M, Olliaro P, Murray HW, 2008. New treatment approach in Indian visceral leishmaniasis: single-dose liposomal amphotericin B followed by short-course oral miltefosine. Clin Infect Dis 47: 1000–1006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sundar S, et al. 2011. Comparison of short-course multidrug treatment with standard therapy for visceral leishmaniasis in India: an open-label, non-inferiority, randomised controlled trial. Lancet 377: 477–486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Thakur CP, Kanyok TP, Pandey AK, Sinha GP, Messick C, Olliaro P, 2000. Treatment of visceral leishmaniasis with injectable paromomycin (aminosidine). An open-label randomized phase-II clinical study. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg 94: 432–433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pagliano P, Carannante N, Rossi M, Gramiccia M, Gradoni L, Faella FS, Gaeta GB, 2005. Visceral leishmaniasis in pregnancy: a case series and a systematic review of the literature. J Antimicrob Chemother 55: 229–233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sundar S, Pandey K, Thakur CP, Jha TK, Rabidas VN, Verma N, Lal CS, Verma D, Alam S, Das P, 2014. Efficacy and safety of amphotericin B emulsion versus liposomal formulation in Indian patients with visceral leishmaniasis: a randomized, Open-Label Study. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 8: e3169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sundar S, Jha TK, Thakur CP, Mishra M, Singh VP, Buffels R, 2003. R Single-dose liposomal amphotericin B in the treatment of visceral leishmaniasis in India: a multicenter study. Clin Infect Dis 37: 800–804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sinha PK, et al. 2010. Effectiveness and safety of liposomal amphotericin b for visceral leishmaniasis under routine program conditions in Bihar, India. Am J Trop Med Hyg 83: 357–364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Thakur CP, 2001. A single high dose treatment of kala-azar with Ambisome (amphotericin B lipid complex): a pilot study. Int J Antimicrob Agents 17: 67–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sundar S, Agrawal G, Rai M, Makharia MK, Murray HW, 2001. Treatment of Indian visceral leishmaniasis with single or daily infusions of low dose liposomal amphotericin B: randomised trial. BMJ 323: 419–422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sundar S, Jha TK, Thakur CP, Mishra M, Singh VR, Buffels R, 2002. Low-dose liposomal amphotericin B in refractory Indian visceral leishmaniasis: a multicenter study. Am J Trop Med Hyg 66: 143–146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]