Abstract.

This study describes the epidemiological and clinical characteristics of leishmaniasis and the pharmacological treatment of this disease in the municipality of Pueblo Rico, Risaralda, between January 2010 and December 2014. An observational study was conducted using information from the clinical records and epidemiological reports of patients diagnosed and confirmed with leishmaniasis of any age and sex, including sociodemographic, clinical, and pharmacological variables of the therapy received. Univariate and bivariate analyses were performed. A total of 539 cases of leishmaniasis were confirmed, with 29.5% occurring in children under 5 years of age. The median age was 10 years, with predominance in males (55.5%). The indigenous Emberá (aboriginal Americans) were the most affected (50.8%), and 93.3% of cases occurred in people living in scattered rural areas. All lesions corresponded to cutaneous leishmaniasis, of which 251 patients had compromise of the upper limbs (46.6%), 221 of the face (41.0%), and 139 of the lower limbs (25.8%). Pentavalent antimony salts (n-methyl glucamine and sodium stibogluconate) were prescribed in 77.6% (N = 418) of the cases; miltefosine was the second most frequently prescribed medication (21.5%, N = 116). The inhabitants of rural areas and the indigenous communities are at a higher risk of acquiring the infection, particularly among infants, which highlights the importance of the biological, social, and demographic factors involved in the disease. There is a need to seek effective public health actions and further research this disease.

INTRODUCTION

Leishmaniasis is a set of zoonotic diseases caused by intracellular protozoans of the genus Leishmania and transmitted to mammals, including humans, by sandflies belonging to the Phlebotomus spp. (in Europe, North Africa, the Middle East, and Asia) or the Lutzomyia spp. (from the southern United States to northern Argentina).1–4 Considered by the World Health Organization (WHO) to be a neglected disease, an estimated 350 million people worldwide are at a risk of acquiring the infection. Moreover, between 1.5 and 2 million cases, 70,000 deaths occur annually.4 This disease is considered prevalent in Central and South America, and a significant number of cases occur annually.3,5,6

The clinical presentation of leishmaniasis is extensive and includes cutaneous, mucosal or mucocutaneous, and visceral forms of affectation.1,6 Among the three clinical forms, cutaneous leishmaniasis is the most common and has the widest geographical distribution. It is considered endemic in more than 70 countries and represents approximately 97% of the cases worldwide.1,4 However, more than two-thirds of new cases appear in six nations, including Colombia.1,5

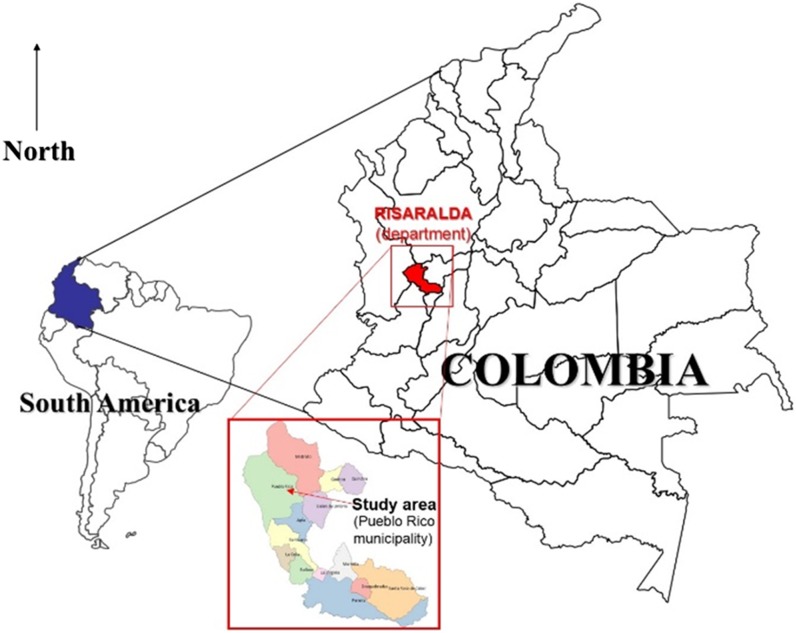

In Colombia, leishmaniasis is endemic throughout nearly the entire territory, and almost 10 million people are at risk, which is attributed to the fact that the disease is mainly rural and that its transmission cycle occurs in regions located below 1,750 masl.1,5 According to the National Institutes of Health of Colombia (Instituto Nacional de Salud), an increase in the number of cases has been recorded over the last decade.1,5 Risaralda is one of the 32 departments (regions) of Colombia. It is located in the west-central region of the country and shares borders with the departments of Valle, Antioquia, Tolima, and Chocó. The municipality of Pueblo Rico (Risaralda) is located on the western mountain range that crosses the country (Figure 1). The total population was estimated to include 12,969 inhabitants in 2013 (76% living in rural areas) and is divided into three main ethnic groups: mestizo (54%), indigenous (Emberá) (32%), and Afro-Colombian (14%). The urban area is at 1,560 masl, but the vast majority of the territory is rural and is located below this altitude, mainly for agricultural labor (7), which determines the presence of different tropical diseases of interest in public health, such as malaria, leishmaniasis, parasitic diseases, which are also favored by conditions, such as poverty, lack of aqueducts, and malnutrition. A study carried out by this research group in this municipality showed a high rate of infections and complications of Plasmodium vivax in children under 5 years of age.7

Figure 1.

Study area, Pueblo Rico municipality, Risaralda department, Colombia, South America. This figure appears in color at www.ajtmh.org.

During 2013, 8,514 cases of cutaneous leishmaniasis were reported in Colombia, including 272 in the department of Risaralda, of which 54% occurred in Pueblo Rico. There were 131 cases of mucosal leishmaniasis; four of these cases originated in Risaralda, but none of them occurred in the municipality mentioned.8

The health system in Colombia consists of three schemes: contributory (people who make contributions in the form of payment to the health system in Colombia), subsidized (population with low capacity to pay and which is subsidized by the state), special (military forces and other groups), and an unaffiliated population. The entire burden of neglected and tropical diseases, such as leishmaniasis, is assumed by the health system which controls the dispensing of treatments and public services network that provides care to the poorest population. The San Rafael Hospital is the only health institution in the locality and is responsible for the care of the population of Pueblo Rico, including patients with leishmaniasis, who, by government policy, are provided care free of charge. The hospital also offers diagnostic tests and pharmacological treatment according to national care guidelines.

Despite the epidemiological relevance of leishmaniasis, the special characteristics of the population, and the burden of the disease, few studies have been performed in this region and particularly in this municipality, where the behavior of leishmaniasis is also unknown. Thus, a study was proposed to describe the epidemiological and clinical characteristics of leishmaniasis and the pharmacological treatment of this disease in the municipality of Pueblo Rico, Risaralda, between January 2010 and December 2014.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study design and setting.

This is a descriptive study with a retrospective collection of information in the population diagnosed with leishmaniasis in the municipality of Pueblo Rico, Risaralda, Colombia, during the period between January 1, 2010 and December 31, 2014. All patients of any age and sex, with skin lesions compatible with cutaneous leishmaniasis and positive lesion smear results for Leishmania spp. amastigotes, were included. Microscopic evaluation was performed by expert personnel in parasitology and microbiology. On approval from the legal representative of the San Rafael Hospital of the municipality of Pueblo Rico, the data included in the epidemiological files and the clinical histories of the patients with a diagnosis of leishmaniasis in the mentioned period were obtained. The analysis of the information and results includes the description of the affected population, the clinical behavior of the disease, and the response to the treatments available and approved for such use by the Ministry of Health of Colombia, for which the following variables were considered:

Data collection and processing.

Sociodemographics.

Sex, age, area of residence (urban or rural), occupation of the patient, ethnicity, type of insurance (contributory, subsidized, without insurance, and special groups), date of the onset of symptoms, and time until diagnosis.

Clinics.

Diagnostic test, location, number and dimension of the lesions, and first time diagnosed or reinfection.

Pharmacologicals.

Treatment received (medication, dose, duration of therapy, and adherence to national guidelines).

Data analysis.

This information was processed in the SPSS® version 22.0 statistical package for Windows®. Frequencies and proportions were determined, and Student’s t test or an analysis of variance was used for the comparison of quantitative variables and the χ2 test for the categorical variables.

Ethics approval.

This research was classified as “without risk”, as established by Resolution 8430 of 1993 of the Ministry of Health of Colombia, which defines the rules of health research and meets the bioethical principles of confidentiality, beneficence, and nonmaleficence of the Declaration of Helsinki. The approval of the Bioethics Committee of the Universidad Tecnológica de Pereira [Technological University of Pereira] was obtained.

RESULTS

A total of 539 cases of leishmaniasis were confirmed and reported in the municipality of Pueblo Rico, Risaralda, between 2010 and 2014, with 29.5% of the cases occurring in children under 5 years of age. The median age in the total population was 10 years. The condition was found to be more common in males (55.5% of cases), and most cases (93.3%) occurred in people living in scattered rural areas. The indigenous Emberá (aboriginal Americans) were the most affected ethnic group (50.8%). Table 1 presents the main sociodemographic characteristics of the population.

Table 1.

Sociodemographic characteristic of 539 patients with diagnosis of leishmaniasis in Pueblo Rico, Colombia, 2010–2014

| Characteristics | Frequency N = 539 | % |

|---|---|---|

| Sociodemographics | ||

| Age (median; interquartile range) | 10.0 (4–23) | – |

| < 5 years of age | 159 | 29.5 |

| Sex: male/female | 299/240 | 55.5/44.5 |

| Type of health insurance: contributory, subsidized, and special groups | 22/434/83 | 4.1/80.5/15.4 |

| Ethnicity: indigenous/mestizo/African-Colombian | 274/225/40 | 50.8/41.7/7.4 |

| Residence: urban/populated-rural/rural-scattered | 1/35/503 | 0.2/6.5/93.3 |

| Occupation | ||

| Students, children, and domiciliary trades | 439 | 81.4 |

| Farmers, drivers, and workers | 90 | 16.7 |

| Professionals, administrators, and office workers | 7 | 1.3 |

| Armed forces and police | 3 | 0.6 |

| Year of detection | ||

| 2010 | 92 | 17.0 |

| 2011 | 48 | 8.9 |

| 2012 | 47 | 8.7 |

| 2013 | 147 | 27.2 |

| 2014 | 206 | 38.2 |

A total of 539 cases diagnosed at the time of observation occurred in 493 patients, five of them in a state of gestation, meeting the following distribution frequency: 450 patients (91.2%) with one episode, 40 patients (8.1%) with two episodes, and three patients (0.6%) with three episodes. No cases were found with human immunodeficiency virus coinfection. The incidence per 100,000 inhabitants/year was 733.5 in 2010, 382.7 in 2011, 364.7 in 2012, 1,172.0 in 2013, and 1,642.4 in 2014.

The time between the onset of symptoms and the diagnostic confirmation of leishmaniasis in the local hospital was established with a median of 17 days (interquartile range: 7–33 days) and a range from 1 to 294 days.

With respect to the clinical findings and epidemiological report, it was found that all lesions corresponded to cutaneous leishmaniasis, confirmed from the lesion smear and evidence of Leishmania spp. amastigotes, through microscopy. In 446 patients (82.7% of cases), a total of 836 lesions were recorded, in which the median area was 1.2 cm2 (interquartile range: 0.25–4 cm2). There was an average of 1.8 lesions per patient (range 1–7 lesions), with a median of one lesion per case (interquartile range: 1–2 lesions). In 49.2% (N = 265) of the cases, a single lesion was presented.

Although the lesions could affect more than one body area, the upper limbs (46.6%) were compromised in 251 cases, the face was compromised in 221 cases (41.0%), the lower limbs were compromised in 139 cases (25.8%), and the trunk was compromised in 65 cases (12.1%). However, in 51 cases (9.5%), there was a simultaneous compromise of the face and upper limbs, in 29 cases (5.3%) of the face and lower limbs, and in 16 cases (2.9%) of the face and trunk. Concomitant lesions occurred in both the upper and lower limbs in 64 (11.9%) cases; in two cases, lesions were present in all of the body segments described. None of the patients presented compromise or damage of the mucosae, and therefore, the diagnosis in all cases was reported as cutaneous leishmaniasis.

Pentavalent antimony salts (n-methyl glucamine and sodium stibogluconate) were prescribed in 77.6% of the cases (N = 418), and the duration of the therapy in most of the cases was 20 days. However, although the recommendation for the duration of treatment in cases of cutaneous leishmaniasis with this group of drugs is 20 days, the medication was administered for a longer period of time in 13 cases (3.1%). Similarly, miltefosine was the second most frequently prescribed drug (21.5% of cases, N = 116); although the treatment recommendation is for 28 days, it was prescribed for a shorter period of time in six cases. In one patient, pentamidine isethionate was prescribed for 28 days, and in the remaining four cases, other unspecified treatments were prescribed. The general adherence to the pharmacological therapy recommended in the guidelines for the clinical care of patients with leishmaniasis was 66.8%.

In patients under 5 years of age (N = 158), treatment was performed with antimonial derivatives (70.3%, N = 111) and miltefosine (25.9%, N = 41). Table 2 shows data for the medication used, dose, the duration of therapy, and adherence to the management guide. No patient received topical treatment, and it was not possible to determine cases of spontaneous cure.

Table 2.

Patterns of use of drugs against leishmaniasis in 539 patients of Pueblo Rico, Colombia, 2010–2014

| Drug | Frequency | Doses (mg/day) | Days of treatment (n/%) | Adherence to guide | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | Median (interquartile range) | 20 | 21 | 22 | 28 | 30 | n | % | |

| N Metyl-Glucamine | 383 | 71.1 | 583.2 (275.4–1,085.4) | 370/96.9 | 2/0.5 | 2/0.5 | 7/1.8 | 1/0.3 | 300 | 78.3 |

| Miltefosine | 116 | 21.5 | 50.0 (50.0–150.0) | 6/5.2 | 0 | 0 | 110/94.8 | 0 | 39 | 33.6 |

| Sodium stibogluconate | 35 | 6.5 | 940.0 (400.0–1,500.0) | 34/97.1 | 0 | 0 | 1/2.9 | 0 | 18 | 51.4 |

| Pentamidine isethionate | 1 | 0.2 | – | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1/100 | 0 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Other drugs | 4 | 0.7 | – | 3/75.0 | 0 | 0 | 1/25.0 | 0 | 0 | 0.0 |

DISCUSSION

Leishmaniasis continues to have important implications for public and environmental health and is considered endemic in multiple areas of the country, including the municipality of Pueblo Rico, Risaralda. This study approached the problem of addressing this little-studied pathology in our area. Moreover, this study highlighted the characteristics of the population most affected, such as children, indigenous Emberá, and inhabitants of rural areas, who, because of their conditions and social determinants of poverty, protein–calorie malnutrition, and poor access to health and educational services, are the groups with the highest burden of this disease in terms of morbid-mortality, complications, and treatment-related adverse effects.9 Data published by the National Department of Statistics of Colombia (DANE, in spanish) show that Pueblo Rico has a high rate of acute and chronic malnutrition in the population under 5 years of age and the highest infant mortality rate due to malnutrition in the region (2.3 Cases/100,000 inhabitants/year), mainly affecting indigenous and rural populations where access to health services is limited.10

The mean age of the population diagnosed was 10 years and approximately 30% were under 5 years of age; thus, the pediatric population is at an increased risk of acquiring infection through the bite of the vector. This context has been shown in other studies in South America, where children with the problems of poverty and lack of access to health care are the most affected.9,10 This situation is furthermore associated with greater intradomiciliary transmission, particularly at night while the infant sleeps (explained by the attraction of the vector generated by the human scent, carbon dioxide, and other elements of respiration in the home environment), which is favored by greater exposure of the body to the mosquito bite.9,11 This also explains the greater compromise of body areas such as the face and upper limbs.

Another argument regarding the most frequent biting site can be supported by the higher rate of transmission and concentration of the vector in places such as housing and its surroundings, which explains how more than 80% of patients were students or people with an intradomiciliary permanence. The preceding, in addition to demonstrating that some population groups are at increased risk of acquiring the infection, highlights the places that must be targets of public health and education actions, seeking to modify or eliminate the biological, social, and environmental determinants that affect these patients and their communities. The behavior of the leishmaniasis found in this population was exclusively of cutaneous compromise, with no cases of visceral leishmaniasis or of the mucosae, conforming to the usual presentation of the pathology in Latin America and Colombia, where cases of cutaneous leishmaniasis predominate.4,9,12–15 In the country, more than 95% of cases occur only with cutaneous involvement; however, the typical mucocutaneous presentation is recognized and is due to infection caused by the new world Leishmania species, among them Leishmania braziliensis, Leishmania panamensis, and Leishmania amazonensis, which have been identified in the study area.4,9,12–14,16 In the same way, the presence of Lutzomya (Nyssomyia) trapidoi, as a vector and transmitter of the cutaneous and mucocutaneous forms of L. panamensis, has been verified; but, only one case of this form of clinical presentation has been recently reported (Leishmaniasis mucosa in an infant), which may suggest that the circulating species of Leishmania in this region are mainly agents with cutaneous tropism.15,17 The incidence of leishmaniasis in this municipality is well above that reported for Colombia, where in 2012, 93.2 cases were estimated per 100,000 inhabitants for the country and when compared with that of Pueblo Rico that year it was about 4 times per year above.8 Moreover, the increase in incidence in the past years, 2013 and 2014, can be explained by climatic variabilities, as previously reported for leishmaniasis in Colombia,18,19 as well as for other vector-borne diseases,20 additionally, an improvement in surveillance processes, with active search of cases in rural areas and native-Americans reservations.

The pharmacological therapy administered to the patients was generally consistent with the treatment guidelines proposed by the National Institutes of Health and the Ministry of Health of Colombia,1 with pentavalent antimony derivatives being the main drugs used in the therapy, followed by miltefosine. These data are very similar to the treatment patterns reported by studies performed in Colombia, Latin America, and Asia.9,11 However, it is disturbing to note that the use of such therapies in infants and children (particularly those under 2 years of age), in whom the medications have fewer studies of effectiveness and safety and where there are no clear and current recommendations for therapy1; this further adds to the problems and differences in the kinetics of these medicines.21,22 This situation aggravates the problem and creates a complex issue for clinicians and health services responsible for the care of these patients, who must decide the best treatment option, taking into account factors, such as age, risk/benefit ratio, severity of the lesions, opportunities for access and adherence, risk of adverse events, and the etiological agent involved. It becomes evident that prevention strategies should constitute the center of attention and action, seeking to avoid the infection and the resulting consequences not only of the disease but also of its treatment.

After a careful review of the literature, few studies describe the epidemiological, clinical, and pharmacological behavior of leishmaniasis in this region of Colombia, so this study provides important information to establish strategies in public health. However, some limitations are present in this study, including the lack of molecular diagnosis and identification of the Leishmania species causing the clinical features because in this area only the diagnosis based on the direct examination of the smear of the lesion is possible; in addition, nonreported data in the clinical record or in the epidemiological report file, spontaneous cure rate, presence of asymptomatic cases; the use of alternative therapies that prevent the consultation to the healthcare system; also, limitations related to the difficulties of access to the information because of the dispersion of cases in the rural area and poor access from health centers, which may determine that patients select other types of treatments, and finally, the lack of pharmacovigilance programs that facilitate and channel reports of adverse reactions and effectiveness of established medical therapy.

CONCLUSIONS

According to these results, the geographic, climatic, and social conditions of this region of Colombia favor the transmission of leishmaniasis, which is present mainly in the inhabitants of the rural area and the indigenous communities, with special involvement of the infantile population; this at-risk population highlights the significance of the biological, social, and demographic factors involved in the cycle of disease transmission. Therefore, it is necessary to seek effective public health actions and conduct a greater amount of research regarding this disease, referred to as one of the neglected diseases by the WHO, in comparison with other disease also referred to as neglected, but there are more relevant diseases such as dengue, malaria, and others not included in this list such as Chikungunya or Zika.23 Furthermore, ecological studies that determine the distribution of the vectors and species in these communities and correlation with clinical presentation, risk maps, searches for intervention and control strategies, and safety and effectiveness studies of the pharmacological therapies used in the general population, and particularly in the pediatric population, should be conducted. In addition, immunogenic and molecular studies will allow us to know not only the distribution of the species but also the resistance to the available treatments.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ministerio de Salud , 2010. Guía de Atención Clínica Integral del Paciente con Leishmaniasis Bogotá, Colombia: Instituto Nacional de Salud, 58. Available at: http://www.ins.gov.co/temas-de-interes/Leishmaniasis%20viceral/02%20Clinica%20Leishmaniasis.pdf. Accessed February 28, 2014.

- 2.Piscopo TV, Mallia Azzopardi C, 2007. Leishmaniasis. Postgrad Med J 83: 649–657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Scott P, 2011. Leishmania—a parasitized parasite. N Engl J Med 364: 1773–1774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Reithinger R, Dujardin JC, Louzir H, Pirmez C, Alexander B, Brooker S, 2007. Cutaneous leishmaniasis. Lancet Infect Dis 7: 581–596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ministerio de Salud , 2015. Leishmaniasis. Nota descriptiva No. 375. Available at: http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs375/es/. Accessed February 17, 2016.

- 6.Kedzierski L, 2011. Leishmaniasis. Hum Vaccin 7: 1204–1214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Medina-Morales DA, Montoya-Franco E, Sanchez-Aristizabal VD, Machado-Alba JE, Rodriguez-Morales AJ, 2016. Severe and benign Plasmodium vivax malaria in Embera (Amerindian) children and adolescents from an endemic municipality in western Colombia. J Infect Public Health 9: 172–180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Instituto Nacional de Salud , 2013. Estadísticas por Municipio. Sistema Nacional de Vigilancia en Salud Pública - SIVIGILA. Available at: http://www.ins.gov.co/lineas-de-accion/Subdireccion-Vigilancia/sivigila/EstadsticasSIVIGILA/Forms/public.aspx. Accessed February 28, 2014.

- 9.Blanco VM, Cossio A, Martinez JD, Saravia NG, 2013. Clinical and epidemiologic profile of cutaneous leishmaniasis in Colombian children: considerations for local treatment. Am J Trop Med Hyg 89: 359–364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Secretaría Departamental de Salud de Risaralda , 2016. Análisis de Situación de Salud con el Modelo de los Determinantes Sociales de Salud (ASIS). Pueblo Rico, Risaralda, Colombia: Municipio de Pueblo Rico. Available at: file:///C:/JorgeMachado/2investigaci%C3%B3n%20audifarma/2-semilleros%20inv/Leishmania/ASIS_Risaralda_2016c.pdf. Accessed February 17, 2016.

- 11.Karami M, Doudi M, Setorki M, 2013. Assessing epidemiology of cutaneous leishmaniasis in Isfahan, Iran. J Vector Borne Dis 50: 30–37. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Alvar J, Velez ID, Bern C, Herrero M, Desjeux P, Cano J, Jannin J, den Boer M, 2012. Leishmaniasis worldwide and global estimates of its incidence. PLoS One 7: e35671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Davies CR, Reithinger R, Campbell-Lendrum D, Feliciangeli D, Borges R, Rodriguez N, 2000. The epidemiology and control of leishmaniasis in Andean countries. Cad Saude Publica 16: 925–950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Corredor A, et al. 1990. Distribution and etiology of leishmaniasis in Colombia. Am J Trop Med Hyg 42: 206–214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ferro C, Fuya P, Perez S, Lugo L, Gonzales G, 2011. Valoración de la ecoepidemiologıa de la leishmaniasis en Colombia a partir de la distribución espacial y ecológica de los insectos vectores [Assessment of the eco-epidemiology of leishmaniasis in Colombia via the spatial and ecological distributions of vector insects]. Biomedica 31: 50–59.25284912 [Google Scholar]

- 16.Strazzulla A, Cocuzza S, Pinzone MR, Postorino MC, Cosentino S, Serra A, Cacopardo B, Nunnari G, 2013. Mucosal leishmaniasis: an underestimated presentation of a neglected disease. BioMed Res Int 2013: 805108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rodriguez-Barraquer I, Gongora R, Prager M, Pacheco R, Montero LM, Navas A, Ferro C, Miranda MC, Saravia NG, 2008. Etiologic agent of an epidemic of cutaneous leishmaniasis in Tolima, Colombia. Am J Trop Med Hyg 78: 276–282. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cardenas R, Sandoval CM, Rodriguez-Morales AJ, Franco-Paredes C, 2006. Impact of climate variability in the occurrence of leishmaniasis in northeastern Colombia. Am J Trop Med Hyg 75: 273–277. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rodriguez-Morales AJ, 2011. Climate change, rainfall, society and disasters in Latin America: relations and needs. Rev Peru Med Exp Salud Publica 28: 165–166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Quintero-Herrera LL, et al. 2015. Potential impact of climatic variability on the epidemiology of dengue in Risaralda, Colombia, 2010–2011. J Infect Public Health 8: 291–297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sundar S, Chakravarty J, 2015. An update on pharmacotherapy for leishmaniasis. Expert Opin Pharmacother 16: 237–252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cruz A, Rainey PM, Herwaldt BL, Stagni G, Palacios R, Trujillo R, Saravia NG, 2007. Pharmacokinetics of antimony in children treated for leishmaniasis with meglumine antimoniate. J Infect Dis 195: 602–608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Perilla-Gonzalez Y, Gomez-Suta D, Delgado-Osorio N, Hurtado-Hurtado N, Baquero-Rodriguez JD, Lopez-Isaza AF, Lagos-Grisales GJ, Villegas S, Rodriguez-Morales AJ, 2014. Study of the scientific production on leishmaniasis in Latin America. Recent Pat Antiinfect Drug Discov 9: 216–222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]