Abstract

Chitin is a carbohydrate polymer with unique pharmacological and immunological properties, however, because of its unwieldy chemistry, the synthesis of discreet sized sub-micron particles has not been well reported. This work describes a facile and flexible method to fabricate biocompatible chitin and dibutyrylchitin sub-micron particles. This technique is based on an oil-in-water emulsification/evaporation method and involves the hydrophobicization of chitin by the addition of labile butyryl groups onto chitin, disrupting intermolecular hydrogen bonds and enabling solubility in the organic solvent used as the oil phase during fabrication. The subsequent removal of butyryl groups post-fabrication through alkaline saponification regenerates native chitin while keeping particles morphology intact. Examples of encapsulation of hydrophobic dyes and nanocrystals are demonstrated, specifically using iron oxide nanocrystals and coumarin 6. The prepared particles had diameters between 300-400 nm for dibutyrylchitin and 500-600 nm for chitin and were highly cytocompatible. Moreover, they were able to encapsulate high amounts of iron oxide nanocrystals and were able to label mammalian cells.

Keywords: dibutyrylchitin, chitin, fluorescence, iron oxide nanocrystals

Graphical abstract

1. Introduction

Chitin is a biopolymer of N-acetyl-D-glucosamine and is found in the cell walls of fungi, the exoskeletons of crustaceans and the digestive tract lining of many insects. This ubiquitous distribution makes chitin the second most abundant polysaccharide on earth; the first being cellulose. Though structurally similar to cellulose, chitin owes its unique properties to its acetamide groups. The degree of acetylation of chitins varies between 85-95%, with its solubility properties being dependent on this percent. Chitin has found widespread use in biomedical pursuits and has been used in drug delivery systems and tissue engineering [1-3].

Moreover, chitin is a potent trigger of innate immune responses. Consequently, several mammalian immune cells such as macrophages produce chitinases that degrade chitin. Recent studies have shown that chitin is a pathogen-associated molecular pattern (PAMP) that activates TLR-2 and regulates macrophage function and acute innate inflammation [4]. Chitin fragments have been shown to exert size-dependent effect on macrophage activity [5], demonstrating untapped potential for use as immunoadjuvants [6-8]. Smaller-sized chitin fragments (<40 μm) have been shown to activate both TNF and IL-10 in macrophages, eliciting an immune response in the absence of excessive inflammation-induced tissue damage [9].

Further, chitin nanocrystals particles are efficient in stabilizing oil-in-water emulsions. The particles can form a layer around the interface of the emulsion globules, hindering the coalescence of the globules (Pickering emulsions) [10, 11].

Whereas it is recognized that chitin is an important and versatile biomaterial, chitin is not broadly used due to its unwieldy chemical nature. Chitin is insoluble in water and most organic solvents, due to its high crystallinity, mostly due its network of intra- and intermolecular hydrogen bonds through acetamide and hydroxyl groups. There are only a few known solvent systems for chitin, such as dimethylacetamide/LiCl, NaOH/(thio)urea, N-methylpyrrolidone/LiCl, ionic liquids (1-butyl-3methyl-imidazolium chloride, 1-allyl-3-methylimidazolium chloride, etc), and saturated CaCl2/methanol [3, 12-17]. Because of the difficulty in performing discrete chemistry with chitin and the inability to synthesize well-formed particles, a chitin derivative called chitosan has been more often used in the development of new drug and gene carriers [18-20]. Chitosan is obtained from the partial deacetylation of chitin under alkaline conditions or enzymatic hydrolysis (using chitin deacetylase). This reduction in the degree of acetylation allows its solubility in acidic aqueous solutions. Other carbohydrate polymers similar in chemical composition (glucose base chains) have also been used for preparing particles, such as starch and cellulose [21, 22]. However, neither starch nor cellulose particles exhibit vaccine-like immunological properties, making chitin a unique carbohydrate material.

Regarding the formulation of chitin particles, in general, chitin fragments are formed by mechanical means without the capacity for encapsulating payloads or for forming sub-micron particles [4, 7]. Currently, the only approach for the preparation of chitin nanogels consists of the dissolution of the polysaccharide in saturated CaCl2/methanol [23] and intense probe sonication. This method prepares nanogels ~ 70-150 nm diameter, depending on the payloads [12, 24-28]. However, this approach has only been achieved with chitins with low acetylation degree (DA, close to 70%) [3]. For example, amorphous chitin with a low DA (~60%) was used to prepare particles with a diameter <300 nm. Its low DA allows the solution of the polysaccharide in a dilute acid solution, allowing the preparation of the particles by ionic cross-linking with pentasodium tripolyphosphate [29]. Also, polyelectrolyte complexation was also used for the preparation of particles of <500 nm with hyaluronic acid and chitin nanofibrils [30]. Importantly, chitin particles have been shown to be suitable for encapsulating active agents such as anti-cancer, anti-aging, or imaging agents [12, 25, 28-30].

To date, there is no method for the preparation of sub-micron particles with chitins of high acetylation degrees. As the unique immune properties of chitin are attributed to the acetamide groups, it is important to fabricate chitin particles with high acetylation. Additionally, chitin particles encapsulating high amounts of magnetic and fluorescent payloads would enable the use of imaging to track labeled cells in many biological applications, from vaccination to cell therapies.

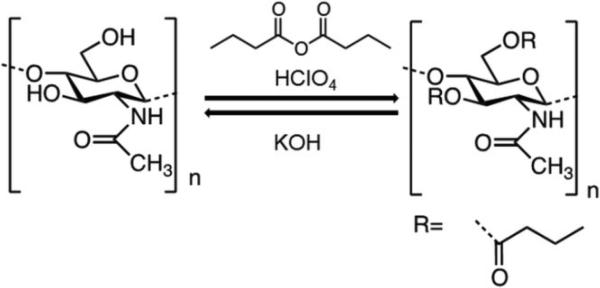

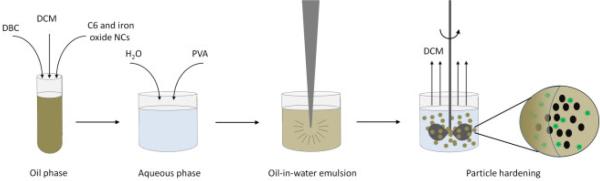

The main objective of this work was to devise a robust strategy of preparing discreet sized DBC and chitin sub-micron particles. To do this, we borrowed a technology originally used to fabricate chitin fibers. Chitin starting material is first functionalized to dibutyrylchitin (DBC) (Fig. 1). DBC presents two butyryl groups, one in position C3 and another in C6, and is soluble in many organic solvents. Taking advantage of the organosolubility of DBC, an oil-in-water emulsification/evaporation method was used to prepare particles (Fig. 2). The butyryl groups could then be removed by alkaline saponification, allowing the regeneration of chitin [31-34].

Fig. 1.

Reversible acylation of chitin.

Fig. 2.

Particle fabrication technique.

While chitin is a promising biomaterial, DBC is also highly biocompatible and it can be degraded by enzymes [35]. Moreover, it has wound-healing and antibacterial properties [36]. Thus, DBC is an interesting new material as well. The only DBC particles prepared to date were synthetized by tip-sonication of DBC solution in ethanol [35].

To prove the suitability of this method for encapsulating hydrophobic compounds, a fluorescent dye (coumarin 6) and iron oxide nanocrystals were loaded into the particles. Finally, its suitability for labeling cells and contrast agents was demonstrated.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Materials

Agarose, ammonium hydroxide solution (NH4OH; 28-30%), butyric anhydride (BA; 98%), chitin from shrimp shells, coumarin 6 (C6; 98%), dibenzyl ether, diethyl ether anhydrous (99%, containing BHT as inhibitor), N,N-dimethylacetamide (DMAc; 99.8%), Dulbecco's Phosphate Buffered Saline (DPBS), 1,2-hexadecanediol (90%), hydrochloric acid (HCl; 37%), iron (III) acetylacetonate (97%), lithium chloride (LiCl, 99%), manganese (II) chloride tetrahydrate (MnCl), oleic acid (90%), oleylamine (70%), paraformaldehyde (95%), penicillin/streptomycin solution (P/S; penicillin 10,000 units and streptomycin 10 mg/mL), perchloric acid (HClO4; 70%), poly(vinyl alcohol) (PVA, Mw 13000-23000, 87-89% hydrolyzed), potassium hydroxide (KOH; 85%) and sodium hydroxide (NaOH; 98%) were purchased in Sigma Aldrich (USA). Phalloidin (Alexa Fluor® 647 phalloidin), Prolong® diamond antifade mountant with DAPI, Dulbecco's Modified Eagle's Medium (DMEM) and Fetal Bovine serum (FBS) were obtained in Life Technologies (USA). Acetone, dichloromethane (DCM), MTT and Triton X100 were bought at Fisher Scientifics (USA), Macron Fine Chemicals (USA), Roche (USA) and Research Product International (USA), respectively. Macrophages Raw 264.7 (ATCC® TIB-71™) was obtained from ATCC (USA).

2.2. DBC synthesis and characterization

Chitin was purified to remove residual proteins and calcium carbonate. Firstly, chitin was deproteinated for 30 minutes in 1 M NaOH (1% w/v) at 80 °C, then demineralized and hydrolyzed with 3 M HCl (1% w/w) at ambient temperature for 24 h. Pure chitin was isolated by centrifugation, and then washed several times with water until the pH was neutral. Finally, it was freeze-dried (overall yield 81.5%).

Afterwards, the chitin was functionalized as described before with slight modifications [32]. Briefly, a fresh acylation mixture of HClO4 and BA at −17 °C was slowly added to chitin powder on ice at a molar ratio of 1:10:1 (chitin:BA:HClO4). The reaction was allowed to proceed on ice for 30 minutes. The exothermic reaction was then kept at room temperature and terminated after 3 h by adding diethyl ether (2 vol equiv). The precipitate was collected and washed successively in water and ether to remove excess butyric acid and butyric anhydride, base-neutralized with NH4OH to pH 7 and dried at room temperature. Afterwards, the product was dissolved in acetone, and non-soluble materials were removed by centrifugation and air-dried.

1H-NMR spectroscopy (500 MHz, Agilent DirectDrive 2) of DBC in chloroform-d and FTIR spectroscopy (Galaxy Series FTIR 3000, Mattson, USA) of chitin and DBC in KBr tablets were performed to analyze the functionalization of the chitin. The degree of acetylation (DA) of the purified chitin was determined by solid state cross-polarization/magic angle spinning 13C-NMR spectroscopy (400 MHz, Varian Infinity-Plus 400). The molecular weight of the chitin after the purification and of dibutyrylchitin (DBC) was measured by viscosimetry using 5% LiCl/DMAc as described by Sugita et al [37]. Briefly, chitin solutions in LiCl/DMAc were prepared at 50 °C (0.0125, 0.02, 0.025, 0.05 and 0.1 g/dL) and stabilized 1 week at 4 °C. The intrinsic viscosity was measured at 25 °C using a Cannon-Fenske viscometer (5354/3, Afora). In the case of DBC, it was necessary to add 4% acetone to the solvent mixture to enable the dissolution of the polymer. The molecular weight was calculated using the Mark-Houwink equation (Eq. 1).

where [η] is the intrinsic viscosity, K = 0.00021, α = 0.88 and Mw is the molecular weight [37].

2.3. Iron oxide nanocrystals preparation

Iron oxide nanocrystals (NCs) were fabricated as described by Sun et al [38]. Briefly, iron acetylacetonate (1.4 g), oleic acid (4 mL), oleylamine (4 mL) and 1,2-hexadecanediol (5.2 g) were dissolved in dibenzyl ether (40 mL) in a round bottom flask connected with a condenser and appropriate traps. The temperature was increased to 200 °C under N2 flow at a 6 °C/min rate and maintained 2 h under the N2 flow. Afterwards, the temperature was increased to 300 °C at a 6 °C/min rate, with no N2 flow and under reflux. After 1 h, the N2 flow was connected again and it was let to cool to room temperature. The NCs were isolated by precipitation with ethanol (2 vol.) and centrifugation (10 min, 12,000 rpm), and washed several times with ethanol.

2.4. Preparation of DBC particles encapsulating C6 and NCs

DBC particles were fabricated using an oil-in-water single emulsion method. Briefly, iron oxide NCs (0, 12.5, 25, 50 or 100 mg), C6 (0.5 mg) and synthesized DBC (50 mg) were dissolved in DCM (1 mL), and added dropwise to 2 mL of 2% (w/v) PVA under vortexing. This solution was then tip-sonicated (10 seconds, 40% amplitude, 3 times), added to 50 mL of deionized water, and allowed to stir for 3 h in a chemical hood to facilitate evaporation of organic solvent. Particles were isolated by centrifugation (8000 rpm, 5 min), washed three times with deionized water and resuspended in 10 mL of water.

All the supernatants were collected in order to estimate the fluorescent dye encapsulation efficiency. Briefly, the supernatants were centrifuged at 12,000 rpm for 20 min, then aliquots were diluted with methanol to reach a final methanol concentration of 90%. The concentrations were measured by fluorescence absorption (λem=485 nm, λex=540 nm) using the corresponding calibration curve (0.4 – 9 ng/mL). The efficiency of encapsulation (EE) was calculated as follows (Eq. 2):

| (Eq. 2) |

where W0 is the amount of C6 added in the particles preparation and Wf the mass of non-encapsulated C6.

2.5. Alkaline saponification titration

Magnetofluorescent chitin particles were regenerated by a 0.25, 0.5 and 1 h alkaline saponification of the freshly prepared DBC particles in 0.5 N KOH at room temperature. The regenerated particles were isolated by centrifugation, washed with distilled water and resuspended in 10 mL of water. Loss of butyryl groups during chitin regeneration was observed using FTIR spectroscopy by dispersing the freeze-dried particles in KBr pellets.

2.6. Particles physicochemical characterization

The hydrodynamic diameter, polydispersity index (PDI) and zeta potential were determined using a ZetaSizer (Malvern, USA). The measurements were collected manually on a dilute suspension of freshly prepared and purified DBC particles and purified chitin particles in milliQ water. The size and PDI were measured by averaging 10 runs, each composed of 12 cycles of three different batches of particles suspensions.

The morphology of the sub-micron particles was analyzed via scanning electron microscopy (SEM; Carl Zeiss Auriga Cross Beam FBI-SEM, Carl Zeiss, Germany). The distribution of NCs within the polymer matrix was analyzed by transmission electron microscopy (TEM; JEOL 2200FS, Jeol, USA). NCs content was quantified by thermogravimetric analysis (TGA 500, TA Instruments, USA), by heating at a rate of 40 °C/min from RT to 1000 °C.

The r2* molar relaxivity was determined using phantoms of the particles at different concentrations. Briefly, 250 μL of an agarose solution in water (1% w/w) at 80 °C was added to 250 μL freshly prepared particles suspensions at different concentrations, vortexed and placed in the freezer to let the hydrogel rapidly form. Then the tubes containing the hydrogels were placed in secondary tubes containing agar 1% with MnCl 100mg/mL, to minimize susceptibility artifacts during the acquisition of T2* maps. The T2* of each sample was determined on a Bruker 7T Biospec. The relaxivity was calculated as the slope of the line between the inverse of the T2* in seconds and the iron concentration in mM.

2.7. Cellular viability following labeling

Cellular compatibility was investigated using macrophages (Raw 264.7). Cell suspensions in DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS and 1% antibiotic solution (100 μL, 200,000 cell/mL) were seeded in 96-well plates and incubated 24 h (37 °C, 5% CO2). Afterwards, 100 μL of each type of DBC and chitin particles suspensions in cell medium were added to the wells containing cells (0.002, 0.005, 0.01, 0.02, 0.05, 0.1, 0.2, 0.5, 1, 2 mg/mL) and incubated another 24 h. Then, the medium was removed, cells were washed three times with DPBS and 100 μL of fresh medium was added. MTT assays were performed as specified by the manufacturer. A negative control (cells not treated with particles) and a blank (medium without cells) were also performed. Briefly, 10 μL of MTT labeling reagent was added to each well and incubated for 4 h (37 °C, 5% CO2), then 100 μL of solubilization solution was added, and the plates were incubated overnight under the same conditions. Afterwards, the absorbance was measured at 550 nm and 690 nm using an ELISA plate reader (Molecular Devices). The absorbance at 550 nm was corrected by the values at 690 nm, and the cellular viability was determined as follows (Eq. 3):

| (Eq. 3) |

2.8. Visualization of cellular labeling by fluorescent microscopy

Raw 264.7 cells (50,00 cells/well, 0.5 mL) were seeded in 4 well-chamber slides (Lab-Tek® II CC2TM chamber slideTM, Nunc, USA) using DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS and 1% antibiotic solution and incubated overnight. Afterwards, the cell medium was replaced by 0.1 mg/mL of each particles suspension in DMEM (0.5 mL) and incubated 1 h at 37 °C, 5% CO2. Then, the particles suspension was removed, cells were washed 3 times with DPBS, fixed with paraformaldehyde (0.2 mL, 4% in DPBS, 10 min), washed again 3 times with DPBS, permeabilized with triton X-100 (0.2 mL, 0.2% in DPBS, 5 min), washed again three times with DPBS, stained with phalloidin (0.2 mL, 75 μM), washed again and air-dried. Then, 1 drop of assembling solution containing DAPI was added to each chamber. A negative control (just fresh cell medium) and a positive control (a saturated solution of C6 in cell medium) were also performed. A Nikon A1Rsi confocal laser scanning microscope equipped with a 60x oil-immersion objective (Nikon) was used for the recording of the images and controlled by Nikon Elements imaging software (NIS).

2.9. Statistical analysis

The quantitative data is represented as mean ± standard deviation (n=3). The statistical analysis was done using a one-way ANOVA, p < 0.001 was considered statistically significant.

3. Results

3.1. DBC synthesis

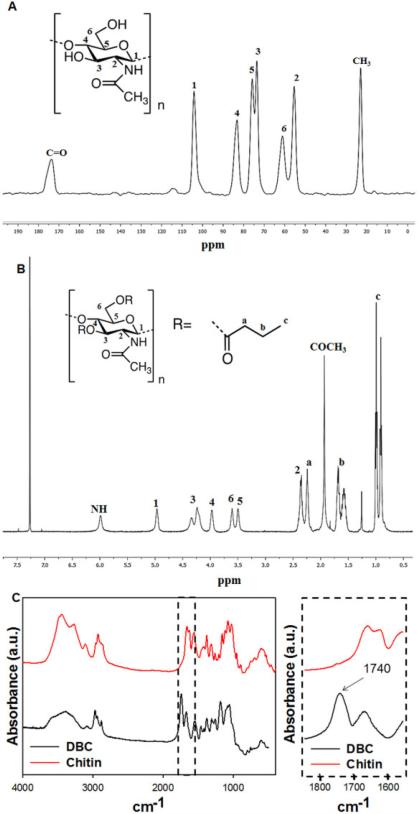

The chitin used for the DBC synthesis was first purified to remove residual proteins and calcium carbonate, with an overall yield of 81.5%. Its degree of acetylation (DA) as calculated by solid state 13C-NMR [39] was 96% (Fig. 3A). The peaks at 1655, 1620 and 1550 cm−1 that appear on the FTIR spectra (Fig. 3B) and the two separate peaks at 74 and 76 ppm in the solid state 13C-NMR show that the chitin was in its alpha form [39-41]. The molecular weight of the chitin as estimated by viscosimetry was 81.7 KDa.

Fig. 3.

DBC and chitin characterization. Solid state 13C-NMR of chitin (A), 1H-NMR of DBC in chloroform-d (B) and FTIR of chitin and DBC (C).

The purified chitin was used for the acylation of DBC, with a final DBC yield of 79%. The resulting DBC was soluble in DCM and acetone and had a molecular weight of 37.5 KDa.

Chitin functionalization was confirmed by FTIR and 1H-NMR in chloroform (Fig. 3B and 3C). 1H-NMR showed peaks at 0.8, 1.6 and 2.2 ppm corresponding to –CH3, –CH2– and –CH–CO– of the added butyric group (Fig. 3A) [32]. The substitution degree was approximately 2 (calculated by averaging the peak areas at 0.8, 1.6 and 2.2 divided by the peak area at 3.9 ppm), indicating that both hydroxyl groups were grafted with the butyric group. The DA was also determined by 1H-NMR, by dividing the peak area at 1.9 ppm (the –COCH3 group) by the peak area at 3.9 ppm, being 94%, proving that the derivatization of chitin did not affect the degree of acetylation. The FTIR spectra also confirmed the acylation of chitin, by the appearance of a new peak at 1740 cm−1 ascribed to the ester carbonyl group (Fig. 3C).

3.2. Particles characterization

DBC particles were first prepared by oil-in-water emulsification/evaporation. Then, in order to remove (deprotect) the butyric groups, and regenerate chitin particles, freshly prepared DBC particles were subjected to alkaline saponification. This regeneration process was optimized to achieve the removal of the butyric groups without compromising morphology and size of particles (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

(A) SEM images of particles treated with KOH 0.5 N at room temperature after 15 min and 1 h of treatment. (B) FTIR of regenerated chitin using KOH 0.5 N at room temperature before and after 15 min, 30 min and 1 h of treatment. (C) FTIR spectra of DBC and chitin particles loaded with C6 and 0% (1), 25% (2), 100% (3) and 200% (4) of NCs.

The optimal deprotection was achieved with 15 min treatment in 0.5 N KOH (Fig. 4B). With 15 min treatment chitin particles maintained their morphology (Fig. 4A), with longer incubation times causing the destruction of the particles. The regeneration of the chitin after the alkaline saponification was confirmed by FTIR (Fig. 4). The loss of absorptions at 1,740 cm−1 (ester C = O) and 2,880-2,980 cm-1 (aliphatic –CH2 and –CH3) together with the appearance of a broad hydrogen-bonded hydroxyl peak at 3,200-3,500 cm−1 and bidentate amide peaks at 1,660 and 1,550 cm−1 after deprotection evidenced this change.

Particles were loaded with a fluorescent dye, C6, and different ratios of NCs (0, 25, 50, 100 and 200 w/w% with respect to DBC). The size, PDI and zeta potential of the particles was measured (Table 1). Freshly prepared DBC particles (not washed) had a hydrodynamic diameter ~ 300 nm with a PDI ~ 0.2, and a zeta potential close to 0. After the purification of the particles by several washes with water and centrifugation, the particles were 300-400 nm, with a slightly negative charge. Regenerated chitin particles were even larger, between 400-600 nm, and, in general, exhibited higher PDI. Chitin particles had a more negative surface charge than the DBC particles.

Table 1.

Hydrodynamic diameter (Dh, nm), polydispersity index (PDI) and zeta potential ( , mV) in water for freshly prepared DBC particles, purified DBC particles and chitin particles, with varying proportion of NCs used during fabrication). Data are the mean values ± standard deviation (n=3).

| Particles type | DBC particles freshly prepared | DBC particles purified | Chitin particles purified | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dh (nm) | PDI | ζ (mV) | Dh (nm) | PDI | ζ (mV) | Dh (nm) | PDI | ζ (mV) | |

| C6-loaded | 252±2 | 0.22±0.01 | −0.67±0.05 | 438±2 | 0.41±0.04 | −6.2±0.5 | 425±3 | 0.35±0.04 | −11.7±0.6 |

| C6 and NC-loaded (25%) | 332±7 | 0.29±0.02 | −0.27±0.18 | 393±4 | 0.29±0.03 | −6.1±0.4 | 584±10 | 0.34±0.01 | −8.8±0.6 |

| C6 and NC-loaded (50%) | 296±3 | 0.25±0.02 | −1.08±0.27 | 332±5 | 0.25±0.01 | −3.7±0.2 | 511±3 | 0.24±0.02 | −7.2±0.6 |

| C6 and NC-loaded (100%) | 274±2 | 0.17±0.01 | −3.44±0.71 | 291±3 | 0.22±0.01 | −3.3±0.5 | 539±18 | 0.33±0.04 | −10.3±0.2 |

| C6 and NC-loaded (200%) | 278±1 | 0.18±0.02 | 2.50±0.85 | 292±4 | 0.24±0.01 | −0.3±0.1 | 384±6 | 0.21±0.03 | −16.4±0.3 |

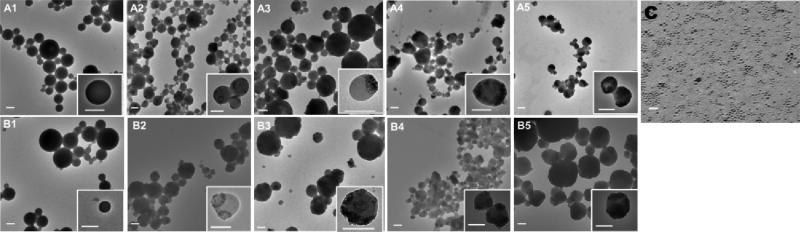

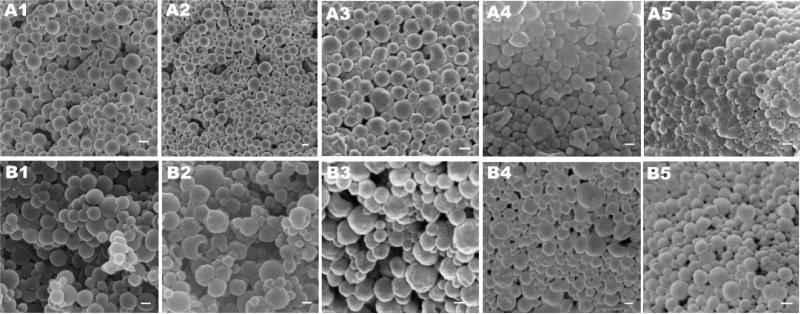

Particles morphology was studied by TEM (Fig. 5) and SEM (Fig. 6). All the particles had spheroidal shape, even after the alkaline saponification process. The SEM images suggested particle aggregation following freeze-drying, thus freshly prepared particles were used for the rest of the experiments (Fig. 6). In addition, the TEM images (Fig. 5) suggest that most NCs are seemingly located at or near the surface of the particles.

Fig. 5.

TEM images of DBC (A1-5) and chitin (B1-5) particles loaded with C6 and 0% (1), 25% (2), 50% (3), 100% (4) and 200% (5) NCs, and TEM of bare NCs (C). Scale bar 200 nm for A and B and 20 nm for C.

Fig. 6.

SEM images of DBC (A) and chitin (B) particles loaded with C6 and 0% (1), 25% (2), 50% (3), 100% (4) and 200% (5) NCs. Scale bar 200 nm.

TGA was used to measure the amount of encapsulated NCs (Table 2). Higher ratios of feed NCs resulted in higher NCs loadings in the particles, with maximal NCs encapsulation of 57.4% w/w for DBC particles and of 68% w/w for chitin particles. Encapsulation efficiency for C6 was >99%, independent of the proportion of iron encapsulated.

Table 2.

NC content and relaxivity of DBC and chitin particles, and C6 encapsulation efficiency (EE %).

| Particle type | DBC particles | Chitin particles | EE (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NC (%) | r2* per mM Fe (s−1mM−1) | NC (%) | r2* per mM Fe (s−1mM−1) | ||

| C6-loaded | - | - | - | - | 99.9±0.01 |

| C6 and NC-loaded (25%) | 16 | 738 | 24 | 283 | 99.8±0.05 |

| C6 and NC-loaded (50%) | 23 | 612 | 37 | 377 | 99.9±0.00 |

| C6 and NC-loaded (100%) | 45 | 783 | 52 | 315 | 99.9±0.01 |

| C6 and NC-loaded (200%) | 57 | 615 | 68 | 399 | 99.9±0.01 |

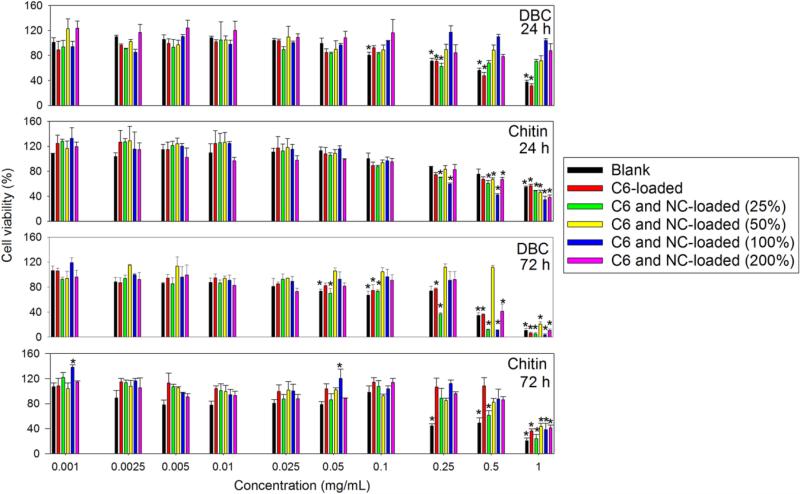

The biocompatibility of the chitin and DBC particles was assayed using a MTT assay, using a macrophages cell line (Raw 264.7). All particles versions were generally well tolerated up to 0.1 mg/mL at both 24 and 72 h (Fig. 7). However, after 72 h of contact, DBC particles presented higher cytotoxicity than the chitin particles at concentrations above 0.5 mg/mL. On the other hand, the NC content inside the particles did not independently impact the biocompatibility of the particles.

Fig. 7.

Viability (%) of Raw 264.7 cells after 24 and 72 h incubation with DBC and chitin particles loaded with C6 (1% w/w with respect to polymer) and NCs (0, 25, 50, 100 and 200% w/w with respect to polymer). Asterisk indicates statistically significant differences with respect to the negative control with p<0.001 (one-way ANOVA with α=0.05).

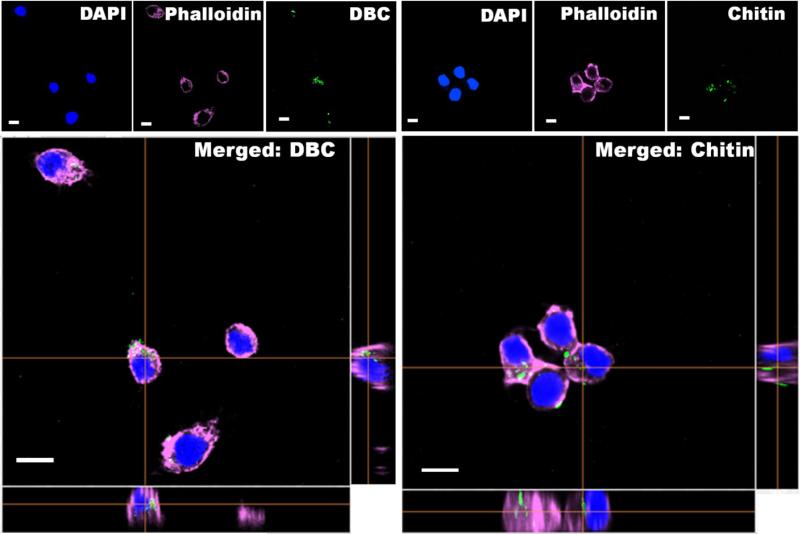

3.3. The use of DBC and chitin particles for cell labeling

The ability of DBC and chitin particles to label macrophages was tested by incubating cells with particles (0.1 mg/mL) for 1 h and analyzing cells via fluorescence microscopy. Incubation with all particles types resulted in high labeling by macrophages, independent of the polymer used or NC content. Confocal fluorescent microscopy employing Z-stack analysis strongly suggests that particles were localized inside cells, as shown for a representative particle, C6 and NC-loaded (50%) (Fig. 8).

Fig. 8.

Cellular labeling of DBC and chitin particles (0.1 mg/mL) after 1h of incubation with Raw 264.7. Images of C6 and 50% loaded NCs in DBC and chitin particles recorded using a fluorescent microscope Images recorded with a confocal microscope of DBC and chitin particles loaded with C6 and 50% of NCs. In blue, nuclei stained with DAPI; in red/pink, cytoskeleton dyed with phalloidin and in green the particles, scale bar 10 μm.

The molar relaxivity of each NC- loaded particles is shown in Table 2. DBC particles had higher r2* (610-780 s−1mM−1 of Fe) than the chitin particles (280-400 s−1mM−1 of Fe).

4. Discussion

Chitin was acylated under heterogeneous conditions, using butyric anhydride as acylation agent and perchloric acid as a catalyst as described in Fig. 1. The grafting of butyric groups onto the polysaccharide backbone disrupts the hydrogen bond formation, and enables solvation of the polymer in organic solvents, such as DCM. The functionalization of chitin with the butyric groups provoked a reduction in the molecular weight of the biopolymer caused by hydrolysis due to perchloric acid [32], but did not affect the DA.

The hydrophobization of chitin with butyric groups enabled the solubility of the polysaccharide in organic solvents, and consequently, the fabrication of particles via a standard oil-in-water emulsification/solvent evaporation procedure, as described in Fig. 2. This technique allows the incorporation of hydrophobic molecules or probes within the particles by dispersing them in the polymeric oil phase and, then, emulsifying the solution in an aqueous solution with an emulsifying agent, in this case PVA. Different proportions of PVA were used to stabilize the particles, with 2% being chosen to render smaller particles sizes (data not shown). Moreover, the use of concentrations of 2% or lower enables higher cell uptake using PLGA particles [42]. Once the DBC particles were prepared, chitin was regenerated by alkaline saponification. Changes in the DA and in the MW of the chitin after the treatment with KOH were not expected due to the low concentration of the base and the short time that the polymer was exposed [43].

To demonstrate the versatility of these particles to encapsulate hydrophobic materials, we encapsulated a hydrophobic fluorescent dye (C6) and oleic acid coated iron oxide NCs, as previously demonstrated with cellulose [44]. Different proportions of NCs were encapsulated inside the polymeric particles to study the amount of iron that could be loaded without affecting particles shape and size. High NC loading will be important for molecular imaging applications. These DBC particles reported herein had a hydrodynamic diameter larger than other DBC particles reported in the literature; diameter ~ 100 nm [35]. Although in the oil-in-water emulsion process we utilized larger particles were formed, our technique provides an alternative encapsulation strategy for labile drugs and proteins, due to the lower amplitudes and sonication time involved. In addition, the flexibility of oil-in-water emulsion nanoparticle fabrication schemes may be better for preserving NP shape and integrity and incorporation of a wider range of encapsulants. Indeed, water-oil-water double emulsion would likely be successful for encapsulating hydrophilic components. The slightly negative charge of DBC particles is likely due to the combination of two factors: residual PVA on the surface of the particles and that a small fraction of the amino groups are protonated at the pH of water which was used for resuspending the DBC particles.

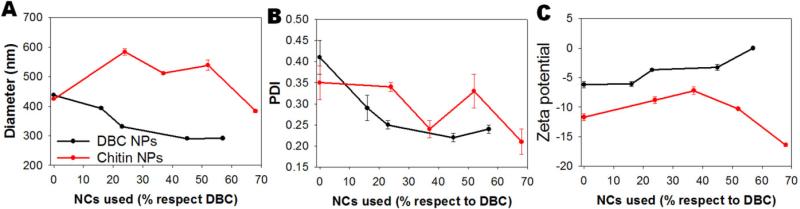

The incorporation of the magnetite NCs in the particles reduced NP size and PDI (Fig. 9), suggesting that the nanocrystals stabilize the particles. This effect has previously been observed before for PLGA particles prepared by emulsification technique [45], with the suggestion that iron oxide particles stabilize the emulsion by reducing the coalescence. This effect would be similar to the effect that particles exert on the Pickering emulsions [46].

Fig. 9.

Effect of NCs content on hydrodynamic diameter (A), PDI (B) and zeta potential (C) on DBC and chitin particles.

Regenerated chitin particles were larger and had higher PDI than DBC particles. This could be explained by a reduction in the hydrophobicity due to the regeneration of the hydroxyls in chitin, which are able to form a larger hydration shell than is possible with DBC. Moreover, swelling studies of chitin nanogels showed the ability of this material to slightly swell at pH 7 [12]. The chitin particles reported herein were larger than previously reported chitin nanogels [12, 24-28], but the method of fabrication, chitin degree of acetylation and molecular weight and composition are incongruous. In addition, there was no relationship between particle size and PDI, and the proportion of NCs encapsulated in the chitin particles (Fig. 9). The chitin particles presented a more negative surface charge than the DBC particles.

The measurements of the zeta potential, sizes and PDI in freshly prepared particles (Table 1) was performed in order to determine whether the centrifugation process was modifying the size of the particles. A slight increase in the size and PDI was observed for all types of particles. Moreover, the zeta potential of freshly prepared particles was closer to neutral than purified particles. Thus, the residual C6, NCs, DBC and PVA, not forming part of the particles, could be interfering in the measurements. With respect to the slightly more negative zeta potential of chitin NP versus DBC particles, the chitin used for the preparation of DBC particles has a degree of acetylation of 93%, which means that only 7% of the amine groups presented have a primary amino group. Moreover, the pKa of this primary amino group is ~ 6.5, which means that most of the amino groups of the DBC will not be protonated, and thus, not expecting a positive charge on the particles. On the other hand it is expected that the PVA imparts some negative charge to the particles [47]. In addition, NCs should present negative charge owing to the oleic acid layer, and their presence on the surface could also cause a more negative superficial charge. These facts together could explain why the DBC and chitin particles present a negative charge. However, the higher negative charge of chitin particles versus DBC particles could be explained by a reduction in the PVA shell that is covering the particles after the KOH treatment, exposing more of the NCs to the surface. It has been shown that in PLGA particles, the presence of PVA allows a reduction in the negative charge of this type of particles [42].

Different ratios of NCs with respect to DBC were assayed to study the loading capacity of the particles. This technique allows the loading of more than 50% of NC. These values are comparable to that previously achieved with cellulose and PLGA particles [44]. The higher encapsulations with chitin, suggests that some of the superficial PVA could be removed from the surface of the particles during the saponification process.

The particles were highly biocompatible even after 72 h of contact with macrophages. The cell viability values obtained for these particles were lower in comparison to previously reported chitin nanogels. However, different cell types were assayed and the particles composition is not the same [12, 24-28].

A low concentration of particles (0.1 mg/mL) was enough for the efficient cell labeling in 1 h. Longer times were not tested, because the C6 can penetrate the cells by itself in longer incubation times (data not shown). This rapid labeling could potentially explain the slightly higher cytotoxicity observed, as fast internalization can affect the ion balance inside the cell. This fact is in agreement with the work already published on chitin nanogels [12, 24].

The r2* values of magnetic chitin particles are similar to the previously reported values for magnetic cellulose and cellulose acetate particles [44]. Interestingly, DBC particles presented slightly higher values. Thus, both magnetic DBC and chitin particles could be useful as contrast agents for MRI.

5. Conclusions

In summary, we have demonstrated a facile and flexible strategy for fabricating chitin and DBC particles and using them as nanocarriers for hydrophobic payloads such as iron oxide NCs and fluorescent dyes. The high cell labeling and the unique surface properties, coupled with their potential as a vaccine adjuvant lend themselves to numerous applications yet to be exploited on a nanoscale. These particles provide the technological basis for new investigations in this area using native chitin or DBC.

Statement of Significance.

We describe a technique to prepare sub-micron particles of highly acetylated chitin (>90%) and dibutyrylchitin and demonstrate their utility as carriers for imaging.

Chitin is a polysaccharide capable of stimulating the immune system, a property that depends on the acetamide groups, but its insolubility limits its use. No method for sub-micron particle preparation with highly acetylated chitins have been published. The only approach for the preparation of sub-micron particles uses low acetylation chitins.

Dibutyrylchitin, a soluble chitin derivative, was used to prepare particles by oil in water emulsification. Butyryl groups were then removed, forming chitin particles.

These particles could be suitable for encapsulation of hydrophobic payloads for drug delivery and cell imaging, as well as, adjuvants for vaccines.

Acknowledgment

BBF is grateful to Per Askeland for his help in SEM and Carmen Alvarez-Lorenzo in the viscosimetry.

Funding Sources

This work was supported by NIH grants DP2 OD004362 and R21 EB017881, and a Michigan State University Foundation Strategic Partnership Grant.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Disclosure statement

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

References

- 1.Ohshima Y, Nishino K, Yonekura Y, Kishimoto S, Wakabayashi S. Clinical application of chitin non-woven fabric as wound dressing. Eur J Plastic Surg. 1987;10:66–9. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ding F, Deng H, Du Y, Shi X, Wang Q. Emerging chitin and chitosan nanofibrous materials for biomedical applications. Nanoscale. 2014;6:9477–93. doi: 10.1039/c4nr02814g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Priya MV, Sabitha M, Jayakumar R. Colloidal chitin nanogels: A plethora of applications under one shell. Carbohyd Polym. 2016;136:609–17. doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2015.09.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Da Silva CA, Hartl D, Liu W, Lee CG, Elias JA. TLR-2 and IL-17A in chitin-induced macrophage activation and acute inflammation. J Immunol. 2008;181:4279–86. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.6.4279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Da Silva CA, Chalouni C, Williams A, Hartl D, Lee CG, Elias JA. Chitin is a size-dependent regulator of macrophage TNF and IL-10 production. J Immunol. 2009;182:3573–82. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0802113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lee CG, Da Silva CA, Lee JY, Hartl D, Elias JA. Chitin regulation of immune responses: an old molecule with new roles. Curr Opin Immunol. 2008;20:684–9. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2008.10.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hamajima K, Kojima Y, Matsui K, Toda Y, Jounai N, Ozaki T, Xin KQ, Strong P, Okuda K. Chitin Micro-Particles (CMP): A Useful Adjuvant for Inducing Viral Specific Immunity when Delivered Intranasally with an HIV-DNA Vaccine. Viral Immunol. 2003;16:541–7. doi: 10.1089/088282403771926355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ichinohe T, Nagata N, Strong P, Tamura S, Takahashi H, Ninomiya A, Imai M, Odagiri T, Tashiro M, Sawa H, Chiba J, Kurata T, Sata T, Hasegawa H. Prophylactic effects of chitin microparticles on highly pathogenic H5N1 influenza virus. J Med Virol. 2007;79:811–9. doi: 10.1002/jmv.20837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Alvarez FJ. The effect of chitin size, shape, source and purification method on immune recognition. Molecules. 2014;19:4433–51. doi: 10.3390/molecules19044433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Magdassi S, Neiroukh Z. Chitin particles as o/w emulsion stabilizers. J Disper Sci Technol. 1990;11:69–74. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tzoumaki MV, Moschakis T, Kiosseoglou V, Biliaderis CG. Oil-in-water emulsions stabilized by chitin nanocrystal particles. Food Hydrocolloid. 2011;25:1521–9. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rejinold NS, Chennazhi KP, Tamura H, Nair SV, Rangasamy J. Multifunctional chitin nanogels for simultaneous drug delivery, bioimaging, and biosensing. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2011;3:3654–65. doi: 10.1021/am200844m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vachoud L, Pochat-Bohatier C, Chakrabandhu Y, Bouyer D, David L. Preparation and characterization of chitin hydrogels by water vapor induced gelation route. Int J Biol Macromol. 2012;51:431–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2012.05.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Poirier M, Charlet G. Chitin fractionation and characterization in N,N-dimethylacetamide lithium chloride solvent system. Carbohyd Polym. 2002;50:363–70. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hu X, Du Y, Tang Y, Wang Q, Feng T, Yang J, Kennedy JF. Solubility and property of chitin in NaOH/urea aqueous solution. Carbohyd Polym. 2007;70:451–8. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Takegawa A, Murakami M, Kaneko Y, Kadokawa J. Preparation of chitin/cellulose composite gels and films with ionic liquids. Carbohyd Polym. 2010;79:85–90. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wang WT, Zhu J, Wang XL, Huang Y, Wang YZ. Dissolution behavior of chitin in ionic liquids. J Macromol Sci Phys. 2010;49:528–41. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Amidi M, Mastrobattista E, Jiskoot W, Hennink WE. Chitosan-based delivery systems for protein therapeutics and antigens. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2010;62:59–82. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2009.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mao S, Sun W, Kissel T. Chitosan-based formulations for delivery of DNA and siRNA. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2010;62:12–27. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2009.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bhattarai N, Gunn J, Zhang M. Chitosan-based hydrogels for controlled, localized drug delivery. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2010;62:83–99. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2009.07.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ayadi F, Bayer IS, Marras S, Athanassiou A. Synthesis of water dispersed nanoparticles from different polysaccharides and their application in drug release. Carbohyd Polym. 2016;136:282–91. doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2015.09.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Le Corre D, Bras J, Dufresne A. Starch Nanoparticles: A Review. Biomacromolecules. 2010;11:1139–53. doi: 10.1021/bm901428y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tamura H, Nagahama H, Tokura S. Preparation of Chitin Hydrogel Under Mild Conditions. Cellulose. 2006;13:357–64. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kumar NA, Rejinold NS, Anjali P, Balakrishnan A, Biswas R, Jayakumar R. Preparation of chitin nanogels containing nickel nanoparticles. Carbohyd Polym. 2013;97:469–74. doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2013.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mangalathillam S, Rejinold NS, Nair A, Lakshmanan VK, Nair SV, Jayakumar R. Curcumin loaded chitin nanogels for skin cancer treatment via the transdermal route. Nanoscale. 2012;4:239–50. doi: 10.1039/c1nr11271f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sabitha M, Sanoj Rejinold N, Nair A, Lakshmanan VK, Nair SV, Jayakumar R. Development and evaluation of 5-fluorouracil loaded chitin nanogels for treatment of skin cancer. Carbohyd Polym. 2013;91:48–57. doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2012.07.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rejinold NS, Nair A, Sabitha M, Chennazhi KP, Tamura H, Nair SV, Jayakumar R. Synthesis, characterization and in vitro cytocompatibility studies of chitin nanogels for biomedical applications. Carbohyd Polym. 2012;87:943–9. doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2011.08.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jayakumar R, Nair A, Rejinold NS, Maya S, Nair SV. Doxorubicin-loaded pH-responsive chitin nanogels for drug delivery to cancer cells. Carbohyd Polym. 2012;87:2352–6. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Smitha KT, Anitha A, Furuike T, Tamura H, Nair VA, Jayakumar R. In vitro evaluation of paclitaxel loaded amorphous chitin nanoparticles for cancer drug delivery. Colloid Surface B. 2013;104:245–53. doi: 10.1016/j.colsurfb.2012.11.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Morganti P, Palombo M, Tishchenko G, Yudin VE, Guarneri F, Cardillo M, Ciotto P, Carezzi F, Morganti G, Fabrizi G. Chitin-hyaluronan nanoparticles: A multifunctional carrier to deliver anti-aging active ingredients through the skin. Cosmetics. 2014;1:40–158. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shen X, Ji Y, Yang Q, Zheng X. Preparation, Characterization, and Rheological Properties of Dibutyrylchitin. J Macromol Sci B. 2010;49:250–8. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Du J, Hsieh YL. Cellulose/chitosan hybrid nanofibers from electrospinning of their ester derivatives. Cellulose. 2008;16:247–60. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Muzzarelli C, Francescangeli O, Tosi G, Muzzarelli RAA. Susceptibility of dibutyryl chitin and regenerated chitin fibres to deacylation and depolymerization by lipases. Carbohyd Polym. 2004;56:137–46. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Szosland L, East GC. The dry spinning od dibutyrylchitin fibers. J Appl Polym Sci. 1995;58:2459–66. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jain T, Kumar S, Dutta PK. Dibutyrylchitin nanoparticles as novel drug carrier. Int J Biol Macromol. 2016;82:1011–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2015.11.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Blasinska A, Drobnik J. Effects of nonwoven mats of di-O-butyrylchitin and related polymers on the process of wound healing. Biomacromolecules. 2008;9:776–82. doi: 10.1021/bm7006373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sugita K, Yang J, Shimojoh M, Kurita K. Influence of trimethylsilylation and detrimethylsilylation on the molecular weight of chitin: Evaluation of viscometry and gel permeation chromatography for molecular weight determination. Polym Bull. 2007;60:449–55. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sun S, Zeng H, Robinson DB, Raoux S, Rice PM, Wang SX, Li G. Monodisperse MFe2O4 (M) Fe, Co, Mn) Nanoparticles. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126:273–9. doi: 10.1021/ja0380852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Van de velde K, Kiekens P. Structure analysis and degree of substitution of chitin, chitosan and dibutyrylchitin by FT-IR spectroscopy and solid state C NMR. Carbohyd Polym. 2004;58:409–16. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Focher B, Naggi A, Torri G, Cosani A, Terbojevich M. Structural differences between chitin polymorphs and their precipitates from solutions - evidence from CP-MAS 13C-NMR, FT-IR and FT-Raman spectroscopy. Carbohyd Polym. 1992;17:97–102. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kaya M, Lelešius E, Nagrockaitė R, Sargin I, Arslan G, Mol A, Baran T, Can E, Bitim B. Differentiations of chitin content and surface morphologies of chitins extracted from male and female grasshopper species. PloS one. 2015;10:e0115531. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0115531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sahoo SK, Panyam J, Prabha S, Labhasetwar V. Residual polyvinyl alcohol associated with poly (d,l-lactide-co-glycolide) nanoparticles affects their physical properties and cellular uptake. J Control Release. 2002;82:105–14. doi: 10.1016/s0168-3659(02)00127-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Einbu A, Naess SN, Elgsaeter A, Varum KM. Solution properties of chitin in alkali. Biomacromolecules. 2004;5:2048–54. doi: 10.1021/bm049710d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Nkansah MK, Thakral D, Shapiro EM. Magnetic poly(lactide-co-glycolide) and cellulose particles for MRI-based cell tracking. Magn Reson Med. 2011;65:1776–85. doi: 10.1002/mrm.22765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Perez A, Mijangos C, Hernandez R. Preparation of hybrid Fe3O4/Poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid) (PLGA) particles by emulsion and evaporation method. Optimization of the experimental parameters. Macromol Symp. 2014;335:62–9. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zoppe JO, Venditti RA, Rojas OJ. Pickering emulsions stabilized by cellulose nanocrystals grafted with thermo-responsive polymer brushes. J Colloid Interface Sci. 2012;369:202–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jcis.2011.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Andreasen S, Chong S-F, Wohl BM, Goldie KN, Zelikin AN. Poly(vinyl alcohol) physical hydrogel nanoparticles, not polymer solutions, exert inhibition of nitric oxide synthesis in cultured macrophages. Biomacromolecules. 2013;14:1687–95. doi: 10.1021/bm400369u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]