Abstract

UCS1025A is a fungal polyketide/alkaloid that displays strong inhibition of telomerase. The structures of UCS1025A and related natural products are featured by a tricyclic furopyrrolizidine connected to a trans-decalin fragment. We mined the genome of a thermophilic fungus and activated the ucs gene cluster to produce UCS1025A at a high titer. Genetic and biochemical analysis revealed a PKS-NRPS assembly line that activates 2S, 3S-methylproline derived from L-isoleucine, followed by Knoevenagel condensation to construct the pyrrolizidine moiety. Oxidation of the 3S-methyl group to a carboxylate leads to an oxa-Michael cyclization and furnishes the furopyrrolizidine. Our work reveals a new strategy used by nature to construct heterocyclic alkaloid-like ring systems using assembly line logic.

Graphical Abstract

Pyrrolizidinone (azabicyclo [3.3.0] octanone) natural products are widespread in nature, many of which exhibit diverse biological properties.1 The ornithine-derived plant pyrrolizidinone alkaloids are potent alkylating agents upon metabolic oxidation and cause significant hepatoxicity.1,2 A family of recently isolated fungal pyrrolizidinone-containing compounds, including CJ-16264, pyrrolizilactone and UCS1025A, display potent antibacterial and antitumor properties (Figure 1A).1 UCS1025A (1) and UCS1025B, isolated from Acremonium sp. KY4917 were shown to be strong telomerase inhibitors.3 Compounds in this group share a hemiaminal-containing pyrrolizidinone core fused with a γ-lactone, giving a furopyrrolizidine that is connected to a decalin fragment. Because of this unique structure feature, these compounds have been subjected to intense total synthesis efforts.4 These efforts have suggested potential biosynthetic routes4, which have remained unknown.

Figure 1.

Structures of fungal pyrrolizidinone natural products are shown in A (pyrrolizidinone highlighted in blue) and a proposed biosynthetic route by a PKS-NRPS is shown in B.

We aimed to elucidate the biosynthetic pathway of 1 as a representative of this family. We hypothesized that the core skeleton of 1 may be derived from a polyketide synthase-nonribosomal peptide synthetase (PKS-NRPS) assembly line. The acyl trans-decalin fragment is likely derived from the polyketide portion that is subjected to intramolecular Diels-Alder (IMDA) cyclization catalyzed by a Diels-Alderase.5 Reductive release of the completed aminoacyl polyketide from the assembly line can form the 3-pyrrolin-2-one structures via an intramolecular Knoevenagel reaction (Figure 1B).6 We reason that if the amino acid incorporated by the NRPS module is either a proline or a modified proline residue, this can potentially afford a rapid route to the pyrrolizidinone. While unprecedented among known fungal PKS-NRPSs, such strategy is different from the Mannich reaction used in plant pathways starting from spermidine (Figure S1).7

We sequenced the producing strain Acremonium sp. KY4917, which revealed three PKS-NRPS containing pathways (Figure S2). The gene cluster in contig 1759 encoded the most number of biosynthetic enzymes, of which the predicted functions are consistent with the structural features of 1 (Figure 2). Genes in the cluster encode the PKS-NRPS (ucsA), its dissociated enoylreductase partner (ucsL), Diels-Alderase (ucsH), hydrolase (ucsC), multiple redox enzymes such as short-chain dehydrogenase/reductase (SDR) (ucsJ), P450 (ucsK) and nonheme iron α-ketoglutarate dependent monooxygenase (ucsF). Notably this cluster encodes an oxidoreductase ucsG that belongs to the pyrroline-5-carboxylate reductase family, members of which catalyze the final reduction step in the biosynthesis of proline.8 Unfortunately, genetic intractability of the producing host and low titer of 1 impaired functional analysis.

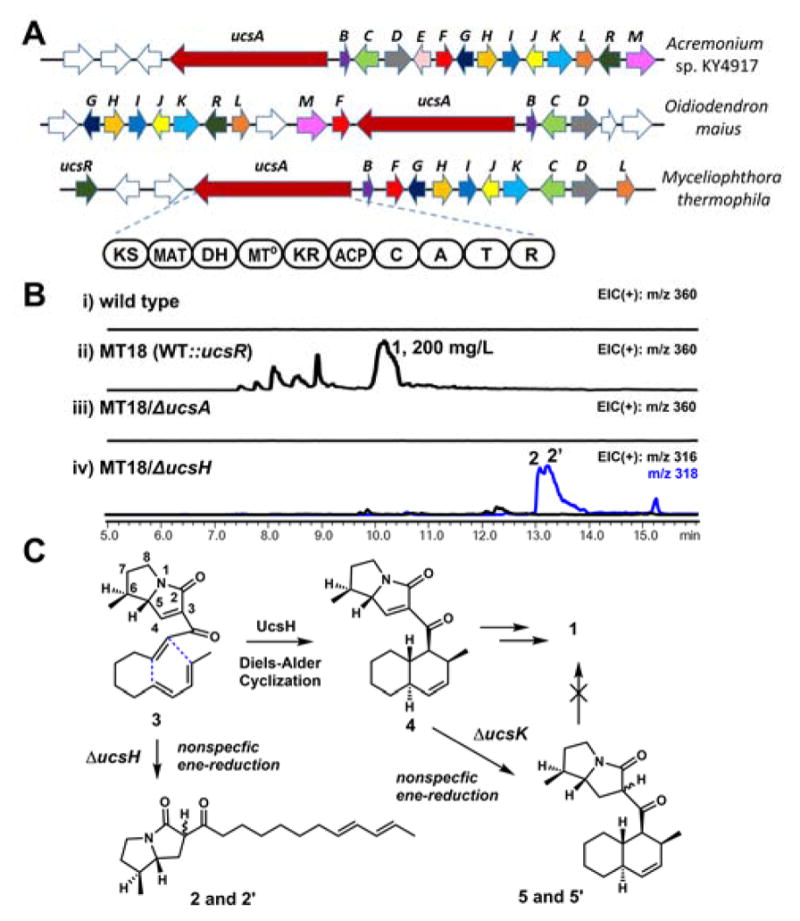

Figure 2.

The ucs cluster is responsible for the biosynthesis of 1. (A) the cluster is found in three organisms; KS, ketosynthase; MAT, malonyl-CoA transferase; DH, dehydratase; MT, methyltransferase; KR, ketoreductase; ACP, acyl carrier protein; C, condensation; A, adenylation; T, thiolation; R, reductase; (B) Genetic analysis of the cluster found in M. thermophila. Shown are chromatograms of extracts from: i) wild type strain; ii) MT18: the ucsR overexpression strain; iii) MT18/ΔucsA; iv) MT18/ΔucsH; (C) 2 is a shunt product formed by the overreduction of the acyclic pyrrolizidinone 3. Similar enereduction by unidentified reductase also affords shunt products such as 5.

To search for a more tractable production host of 1, we used the putative ucs cluster as a lead and searched for highly similar gene clusters in the sequenced genome database. Two clusters with high gene synteny and sequence identity were found in the genomes of the thermophilic fungus Myceliophthora thermophila and the metal-tolerant Oidiodendron maius (Table S2). We previously identified the biosynthetic gene cluster of myceliothermophin A (Figure 1), which is a pyrrolinone produced by a different PKS-NRPS cluster from M. thermophila.9 The organism has well-established genetic tools.10 However, after growth on different cultural conditions, no production of 1 can be detected from the extracts (Figure 2B, i).

To identify the natural product encoded in the ucs cluster, we overexpressed a putative GAL4-like transcriptional regulator encoded by ucsR in the cluster, using the constitutive gpdA promoter.11 The resulting strain MT18 produced 1 (Figure S12–S13, Table S3) at a high titer (~ 200 mg/L) (Figure 2B, ii), as confirmed by comparison to a synthetic standard provided by the Kan group.4c The role of PKS-NRPS UcsA was established with the deletion strain ΔucsA, which abolished 1 production.

Having confirmed that 1 is derived from a PKS-NRPS assembly line, we then turned to the identify the amino acid residue that is incorporated. To obtain an early intermediate or shunt product, we generated the MT18/ΔucsH strain in which the Diels-Alderase was inactivated. Our work with myceliothermophin confirmed proteins with sequence homology to UcsH catalyze trans-decalin formation immediately following the Knoevenagel condensation.9 MT18/ΔucsH did not produce 1, instead accumulated a pair of diastereoisomers (2 and 2′) (Figure 2B, iv). The elucidated structure showed the compounds contain pyrrolizidine (Figure S14–S19, Table S4). The acyclic polyketide portion contains the terminal diene, however the α–β olefin that serves as the dienophile has been reduced. The overreduction is likely caused by unidentified, endogenous enereductases acting on 3 in the absence of UcsH (Figure 2C). Similarly, the C3–C4 double bond in 3 that formed as a result of the Knoevenagel condensation is also reduced, affording the saturated pyrrolizidinone. This overreduction leads to racemization of the α-carbon and formation of the diastereomeric pair. The methyl substitution at C6 suggests that 3-methylproline is incorporated by the NRPS module of UcsA. The absolute stereochemistry at C5 and C6 of 2 cannot be determined with NMR analysis, although from NOESY analysis the attached hydrogens are trans to each other. Subsequent studies presented below revealed that both carbons should be of S-configurations.

The methyl group at C6 of 2 (and by inference in 3) points to a possible route to construction of the furopyrrolizidine. We hypothesize the methyl group must first be subjected to six electron oxidation to yield the carboxylate. This sets up an intramolecular oxa-Michael addition to afford the tricyclic ring system. This end-game strategy has been utilized in several synthetic approaches towards 1.4c–4f To identify the enzyme that can catalyze methyl oxidation of 3, we generated a knockout strain of the P450 UcsK (MT18/ΔucsK) (Figure S4). P450 enzymes that perform iterative oxidation of methyl to carboxylate have been found in several natural product pathways.12 Analysis of the extract confirmed the loss of 1, and the accumulation of a pair of diastereomers 5 and 5′ (Figure S20–S25, Table S5) (Figure 3A). Structural analysis revealed that the pair are trans-decalin compounds and are methylated at C6 of the pyrrolizidinone (Figure 3A). As with 2, nonspecific ene reduction of the C3–C4 position led to racemization at the α-position (C3). As the double bond at C3–C4 is required for the oxa-Michael addition, we expected 5 to be a shunt product (Figure 2C). This was confirmed when addition of 5 to MT18/ΔucsA could not restore the biosynthesis of 1.

Figure 3.

Functional assignment of oxygenases in the ucs cluster. (A) Characterization of P450 UcsK: i) Extractedion chromatogram (EIC) of 5 produced by MT18/ΔucsK; ii) and iii) LC-MS analysis of the biochemical assays of UcsK using yeast microsomal fractions; (B) The α-KG dependent enzyme UcsF catalyzes the oxidation of L-isoleucine to yield (4S, 5S)-4-methylpyrroline-5-carboxylate 10; i) and ii) Analysis of UcsF assays using Fmoc-Cl as the derivatization agent to detect 8; iii) and iv) Analysis of UcsF assays using o-aminobenzaldehyde (o-AB) as the derivatization agent to detect 10.

UcsK was cloned from M. thermophila cDNA and expressed in Saccharomyces cerevisiae RC01,13 which contains an integrated copy of cytochrome P450 reductase (CPR) from A. terreus. Microsomal fractions containing UcsK and CPR were isolated and assayed for oxidation of 5 and 5′. UcsK-containing microsomes converted the starting material to two pairs of diastereomers with MW increases of 16 Da (6 and 6′) and 30 Da (7 and 7′) (Figure 3A). Structural elucidation showed 6 and 6′ (Figure S26–S31, Table S6) are hydroxylated versions of 5 and 5′, respectively, whereas 7 and 7′ (Figure S32–S37, Table S7) are the carboxylated products. These results confirmed that UcsK is indeed the enzyme that oxidizes the methyl pyrrolizidinone to the carboxylated intermediate. The likely true substrate of UcsK is C3–C4 unsaturated 4 (Figure 2C), as feeding of either 6 or 7 to MT18/ΔucsA did not restore production of 1.

Methylproline is a building block for both bacterial and fungal NRPS-derived natural products.14 However, methylproline has not been reported to be a building block for PKS-NRPS assembly lines. The common 4-methylproline, found in molecules such as echinocandin and griselimycin, is derived from oxidation of the δ-methyl in L-leucine by a nonheme iron α-ketoglutarate dependent monooxygenase, such as EcdK from the echinocandin biosynthetic pathway.15 To form 3-methylproline as proposed here, a parallel δ-methyl oxidation/cyclization sequence starting from isoleucine can be envisioned. The lone α-KG oxygenase UcsF in the gene cluster shows moderate sequence homology (38% identity and 57% similarity) to EcdK, and is therefore a candidate enzyme to catalyze the initial tandem hydroxylation of L-isoleucine to yield β-methyl-glutamic acid-δ-semialdehyde 9, that can exist in equilibrium with the cyclic imine methyl-Δ1-pyrroline-5-carboxylic acid 10 (Figure 3B). Reduction to 3-methylproline can be catalyzed by the pyrroline-5-carboxylate reductase homolog UcsG.

We generated the MT18/ΔucsF strain, which led to the complete abolishment of all products and confirmed UcsF involvement early in the pathway (Figure S8). To prove that UcsF is involved in 3-methylproline biosynthesis and to delineate the product stereochemistry, we performed chemical complementation using both (2S, 3S) and (2S, 3R)-3-methyproline. The amino acids were synthesized following published protocols (Supplemental Information).16 Whereas supplementation with (2S, 3S)-3-methylproline restored the production of 1, feeding of the (2S, 3R) enantiomer did not lead to any restoration (Figure S8). This allowed assignment of the absolute stereochemistry of 2 and 5, as well related products, as shown in Figures 2 and 3. UcsF was expressed and purified from E. coli and assayed in the presence of different branched chain amino acids (BCAAs). FMOC-Cl and o-aminobenzaldehyde (o-AB) were used to derivatize hydroxylated product such as 8, and cyclic imine such as 10, respectively.15a UcsF readily oxidized L-isoleucine to yield both 8 and 10, as detected by mass and UV absorption (Figure 3B). No activity was detected in the presence of allo-L-isoleucine (Figure S11), further confirming (2S, 3S)-methylproline should be substrate of the PKS-NRPS. Weak activity (<10% of that towards L-isoleucine) was displayed by UcsF towards L-leucine (Figure S11), demonstrating its substrate selectivity towards the γ-branched L-isoleucine. UcsF therefore adds to a panel of C-H functionalization oxygenases that can be used for synthesis of complex molecules from BCAAs.15c To demonstrate that the UcsF/UcsG pair is sufficient to synthesize (2S, 3S)-3-methylproline, we performed heterologous reconstitution of UcsA, L, H, F and G in Aspergillus nidulans, which lead to the production of 5 and 5′ (Figure S9). The C3–C4 double bond is similarly reduced in the heterologous host.

We propose a putative biosynthetic pathway for 1 (Figure 4). The functions of the PKS-NRPS, Diels-Alderase, and the P450 leading to the intermediate 11 are established from knockout and biochemical assays. The S-configured C6-carboxylate in 11 is too distant to undergo the intramolecular oxa-Michael addition at C4. As a result, epimerization of C6 to give R-stereochemistry must take place later in the biosynthetic pathway. Our inability to isolate inter-mediates due to nonspecific enereduction makes reconstitution of the remaining steps unfeasible. One additional knockout, however, provided insights into the epimerization step. Inactivation of ucsJ encoding a SDR led to the accumulation of a shunt product 15 (Figure S38–S43, Table S8) in which a double bond is introduced between C5 and C6, thereby scrambling the existing stereochemistry at both positions. We propose the double bond can be formed from the uncatalyzed air oxidation of 11 to 12, as observed in the formation of myceliothermophin E.9 UcsJ thus likely plays a critical role in stereoselective reduction of the C5–C6 double bond to afford the required R-configured carboxylate group in 13. Enolization and oxidation at C5 by an unidentified enzyme affords 14. Similar hydroxylation is also observed in myceliothermophin A17 and quinolactacins.18 As seen in multiple synthetic approaches, 14 can undergo oxa-Michael cyclization to yield 1.4c–4f

Figure 4.

Proposed biosynthetic pathway of UCS1025A based on biochemical and genetic evidences present in this work.

Overall, the biosynthetic pathway of 1 is concise given the structural complexity of the pentacyclic compound. The efficiency is a result of two key strategies revealed in this work: 1) the use of PKS-NRPS assembly line to incorporate 3-methylproline and generate the pyrrolizidine fragment from Knoevenagel condensation; 2) the combination of activities from multifunctional oxygenases such as UcsK, and nonenzymatic oxidation of pyrrolizidinone to form the compact but densely decorated furopyrrolizidinone ring system. Other members of the furopyrrolizidinone family of compounds are expected to be biosynthesized using the same strategies (Figure S48).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the NIH (1DP1GM106413 and 1R35GM118056 to YT, and JSPS Program for Advancing Strategic International Networks to Accelerate the Circulation of Talented Researchers (No. G2604 to K.W.). TY would like to acknowledge financial support from Shenzhen Peacock Plan (KQTD2015071714043444). Chemical characterization studies were supported by shared instrumentation grants from the NSF (CHE-1048804) and the NIH NCRR (S10RR025631). We thank Prof. Toshiyuki Kan at University of Shizuoka for a synthetic standard of UCS1025.

Footnotes

Experimental details, spectroscopic and computational data. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

References

- 1.(a) Robertson J, Stevens K. Nat Prod Rep. 2014;31:1721–1788. doi: 10.1039/c4np00055b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Robertson J, Stevens K. Nat Prod Rep. 2017;34:62–89. doi: 10.1039/c5np00076a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Neuman MG, Cohen L, Opris M, Nanau RM, Hyunjin J. J Pharm Pharm Sci. 2015;18:825–843. doi: 10.18433/j3bg7j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.(a) Nakai R, Ogawa H, Asai A, Ando K, Agatsuma T, Matsumiya S, Yamashita Y, Mizukami T. J Antibiot (Tokyo) 2000;53:294–296. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.53.294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Agatsuma T, Akama T, Nara S, Matsumiya S, Nakai R, Ogawa H, Otaki S, Ikeda S, Saitoh Y, Kanda Y. Org Lett. 2002;4:4387–4390. doi: 10.1021/ol026923b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.(a) Nicolaou KC, Pulukuri KK, Rigol S, Buchman M, Shah AA, Cen N, McCurry MD, Beabout K, Shamoo Y. J Am Chem Soc. 2017;139:15868–15877. doi: 10.1021/jacs.7b08749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Nicolaou KC, Shah AA, Korman H, Khan T, Shi L, Worawalai W, Theodorakis EA. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2015;54:9203–9208. doi: 10.1002/anie.201504337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Uchida K, Ogawa T, Yasuda Y, Mimura H, Fujimoto T, Fukuyama T, Wakimoto T, Asakawa T, Hamashima Y, Kan T. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2012;51:12850–12853. doi: 10.1002/anie.201207800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) de Figueiredo RM, Fröhlich R, Christmann M. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2007;46:2883–2886. doi: 10.1002/anie.200605035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Hoye TR, Dvornikovs V. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:2550–2551. doi: 10.1021/ja0581999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (f) Lambert TH, Danishefsky SJ. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:426–427. doi: 10.1021/ja0574567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Li G, Kusari S, Spiteller M. Nat Prod Rep. 2014;31:1175–1201. doi: 10.1039/c4np00031e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Boettger D, Hertweck C. ChemBioChem. 2013;14:28–42. doi: 10.1002/cbic.201200624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hartmann T, Ober D. Biosynthesis and metabolism of pyrrolizidine alkaloids in plants and specialized insect herbivores. In: Leeper FJ, Vederas JC, editors. Biosynthesis: Aromatic Polyketides, Isoprenoids, Alkaloids. Vol. 209. Springer Berlin Heidelberg; Berlin, Heidelberg: 2000. pp. 207–244. Topics in Current Chemistry. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pérez-Arellano I, Carmona-Alvarez F, Martínez AI, Rodríguez-Díaz J, Cervera J. Protein Sci. 2010;19:372–382. doi: 10.1002/pro.340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Li L, Yu P, Tang M-C, Zou Y, Gao S-S, Hung Y-S, Zhao M, Watanabe K, Houk KN, Tang Y. J Am Chem Soc. 2016;138:15837–15840. doi: 10.1021/jacs.6b10452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Xu J, Li J, Lin L, Liu Q, Sun W, Huang B, Tian C. BMC Biotechnol. 2015;15:35. doi: 10.1186/s12896-015-0165-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.(a) Tsunematsu Y, Ishikawa N, Wakana D, Goda Y, Noguchi H, Moriya H, Hotta K, Watanabe K. Nat Chem Biol. 2013;9:818–825. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.1366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Sato M, Dander JE, Sato C, Hung YS, Gao SS, Tang MC, Hang L, Winter JM, Garg NK, Watanabe K, Tang Y. J Am Chem Soc. 2017;139:5317–5320. doi: 10.1021/jacs.7b02432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.(a) Li J, Tang X, Awakawa T, Moore BS. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2017;56:12234–12239. doi: 10.1002/anie.201705239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Du L, Ma L, Qi F, Zheng X, Jiang C, Li A, Wan X, Liu SJ, Li S. J Biol Chem. 2016;291:6583–6594. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M115.695320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Ro DK, Paradise EM, Ouellet M, Fisher KJ, Newman KL, Ndungu JM, Ho KA, Eachus RA, Ham TS, Kirby J, Chang MC, Withers ST, Shiba Y, Sarpong R, Keasling JD. Nature. 2006;440:940–943. doi: 10.1038/nature04640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Tudzynski B, Hedden P, Carrera E, Gaskin P. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2001;67:3514–3522. doi: 10.1128/AEM.67.8.3514-3522.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tang MC, Lin HC, Li DH, Zou Y, Li J, Xu W, Cacho RA, Hillenmeyer ME, Garg NK, Tang Y. J Am Chem Soc. 2015;137:13724–13727. doi: 10.1021/jacs.5b06108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tang MC, Zou Y, Watanabe K, Walsh CT, Tang Y. Chem Rev. 2017;117:5226–5333. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemrev.6b00478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.(a) Jiang W, Cacho RA, Chiou G, Garg NK, Tang Y, Walsh CT. J Am Chem Soc. 2013;135:4457–4466. doi: 10.1021/ja312572v. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Lukat P, Katsuyama Y, Wenzel S, Binz T, König C, Blankenfeldt W, Brönstrup M, Müller R. Chem Sci. 2017;8:7521–7527. doi: 10.1039/c7sc02622f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Zwick CR, Renata H. J Am Chem Soc. 2018;140:1165–1169. doi: 10.1021/jacs.7b12918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Herdeis C, Hubmann HP. Tetrahedron: Asymmetry. 1994;5:351–354. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yang YL, Lu CP, Chen MY, Chen KY, Wu YC, Wu SH. Chem Eur J. 2007;13:6985–6991. doi: 10.1002/chem.200700038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Clark B, Capon RJ, Lacey E, Tennant S, Gill JH. Org Biomol Chem. 2006;4:1512–1519. doi: 10.1039/b600959j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.