Abstract

Background

Patients with malignant high-grade glioma (HGG) have significant supportive and palliative care needs, yet few tailored guidelines exist to inform practice. This study sought to develop an HGG framework of supportive and palliative care informed by needs reported by patients, families, and health care professionals (HCPs).

Methods

This study integrates a mixed-methods research program involving: (i) exploring experiences through systematic literature review and qualitative study (10 patients, 23 carers, and 36 HCPs); and (ii) an epidemiological cohort study (N = 1821) describing care of cases of HGG in Victoria, Australia using linked hospital datasets. Recommendations based on these studies were developed by a multidisciplinary advisory committee for a framework of supportive and palliative care based on the findings of (i) and (ii).

Results

Key principles guiding framework development were that care: (i) aligns with patient/family caregiver needs according to illness transition points; (ii) involves continuous monitoring of patient/family caregiver needs; (iii) be proactive in response to anticipated concerns; (iv) includes routine bereavement support; and (v) involves appropriate partnership with patients/families. Framework components and resulting activities designed to address unmet needs were enacted at illness transition points and included coordination, repeated assessment, staged information provision according to the illness transition, proactive responses and referral systems, and specific regular inquiry of patients’ and family caregivers’ concerns.

Conclusion

This evidence-based, collaborative framework of supportive and palliative care provides an approach for patients with HGG that is responsive, relevant, and sustainable. This conceptual framework requires evaluation in robust clinical trials.

Keywords: guidelines, high grade glioma, palliative care, supportive care

Importance of the study

Despite treatment advances, supportive and palliative care continue to be an important component of care for people with HGG. This study synthesizes a program of work examining the needs and care of patients with HGG and their family caregivers, to develop a unique tailored framework of supportive and palliative care based on key transition points in the illness course. The framework is underpinned by guiding principles, including that care: be aligned with patient/family caregiver needs according to illness transition point; involve continuous monitoring of patient/family caregiver needs; be proactive in response to anticipated or expressed concerns; includes routine bereavement support; and involves partnership with patients and families. These principles are articulated in the framework through suggested service activities at illness transition points (diagnosis, conclusion of radiotherapy, tumor recurrence, deterioration to death, following death).

High-grade gliomas (HGGs) are rare but incurable primary tumors of the central nervous system, affecting 5.54 per 100000 Americans between 2005 and 20091 and 7.3 and 4.6 per 100000 male and female Victorians, respectively, in Australia in 2015.1,2 HGGs include World Health Organization (WHO) grade III anaplastic astrocytomas, oligodendrogliomas, and oligoastrocytomas and WHO grade IV glioblastomas and their variants.3 Optimum multimodal treatment involves surgical resection followed by postoperative radiotherapy and concurrent adjuvant temozolomide,4 with median survival of 14.6 months in patients with grade IV disease treated accordingly.5 Nevertheless HGG remains a poor prognosis cancer, and particularly so for the group of up to 20% of patients who are not fit for this multimodal treatment.6,7

In Australia, management of HGG is primarily provided by neuro-oncology units in tertiary hospitals. Treatment pathways, consistent with international glioma guidelines,4 provide a framework to guide care, and while they variably mention the provision of palliative and supportive care, the content, timing, and details of these services are frequently not described.8 More recent guidelines are increasingly acknowledging and endorsing the integration of palliative and supportive care across the illness course.9

The unique combination of physical, cognitive, and generalized cancer symptoms associated with HGG and its treatment suggests high levels of palliative and supportive care need for patients with HGG and their family caregivers. There is a need for a framework of providing supportive and palliative care which can be directly embedded within the expected HGG disease trajectory and existing care systems.

A framework of care which addresses all aspects of supportive and palliative care and is relevant and responsive to the needs raised by patients with HGG, their family caregivers, and health care professionals (HCPs) still requires careful articulation. The aim of this project was to develop recommendations for a clinical service delivery framework of palliative and supportive care for people with HGG. These recommendations are based upon data emerging from a mixed method program of work undertaken to explore the palliative and supportive care needs of this cohort and reported previously.10–14 The program of work sought, for people with HGG and their family caregivers, to (i) understand the needs and experiences of care, including service strengths and gaps according to patients, families, and HCPs; (ii) explore health care utilization from diagnosis until death; and (iii) develop a framework of palliative and supportive care service delivery that responds to these needs and the deficiencies of current care models. While the focus of this manuscript is to report on the recommended framework of care, background data from the previous studies supporting the framework’s components are presented in order to provide context.

Methods

Design

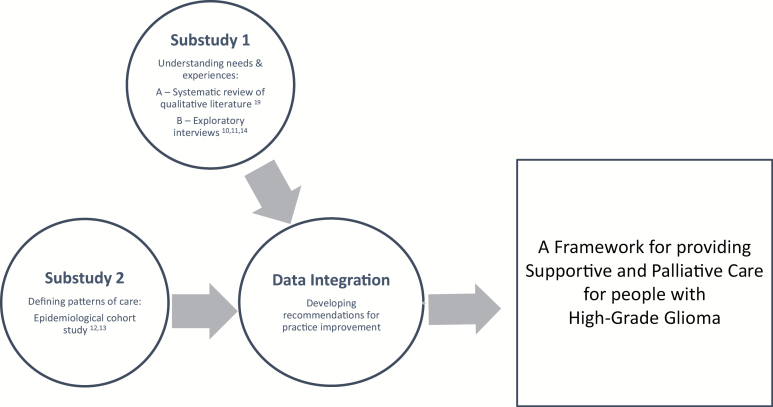

In our program of work, we undertook a mixed-methods sequential approach to examine the palliative and supportive care needs of patients with HGG and their family caregivers (Fig. 1). Using the Medical Research Council framework for developing and evaluating complex interventions,15 development of the framework was informed by a series of substudies (qualitative and epidemiological).10–14 The data from the substudies were then presented to an advisory group and integrated, and a series of key principles to guide the framework of care were developed.16 The principles were formulated to both directly reflect the needs raised in previous empirical work and to be consistent with and adapted from those recommended principles within the Institute of Medicine Crossing the Quality Chasm report.17 In turn, the formulated principles led to the development of a series of core components of the framework to facilitate service delivery for an approach to providing supportive and palliative care to patients with HGG and their families (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Mixed-methods sequential design.

Results of all the substudies have been published elsewhere,10–14,18,19 with key findings described here in brief to contextualize the recommendations. The presentation as a single coherent body of work and the resulting development of practice recommendations is the original contribution of the study.

Substudies

Substudies 1: Qualitative studies defining needs and experiences: Substudy 1A: A systematic review of the qualitative literature to understand the needs and experiences of patients with HGG and their family caregivers.19

Substudy 1B: A qualitative study exploring views of patients, current and bereaved family caregivers, and HCPs regarding the care of people with HGG conducted in Victoria, Australia.10,11,14

Substudy 2: Describing service use: An epidemiological cohort study of the health care utilization of patients admitted to hospitals in Victoria, Australia from diagnosis of HGG until death, including the service use at the end of life and place of death.12,13

Setting: Victoria, Australia has a population of 5.6 million people, with universal access to publicly funded medical care. HGG is managed in specialized neuro-oncology units. Specialist palliative care services are organized into 3 main areas of service provision: acute hospital consultancy services; community palliative care services providing care in the patient’s residence; and specialist inpatient palliative care units. A patient may receive care from one or each of these areas of service, including concurrent acute care and palliative care, according to their needs and illness course.

Substudies 1: qualitative studies defining needs and experiences

The needs and experiences of patients with HGG and their family caregivers were explored using qualitative methods. Firstly (Substudy 1A), through a systematic review of earlier qualitative literature from 2000–2010 which focused on supportive and palliative care needs of people with HGG or their caregivers, identifying 21 qualitative studies reporting on the views of a total of 219 patients and 301 family carers.19

Secondly (Substudy 1B), exploratory interviews were undertaken with patients (N = 10), current and bereaved carers (N = 22), and HCPs (N = 35). Specifically, these interviews focused on palliative care needs across the illness experience, along with the strengths and gaps in current systems of care. Analysis proceeded according to a thematic approach. The study was approved by the institutional human research and ethics committees at both recruiting hospitals. Detailed methodology is described elsewhere.10,11,14

Substudy 2: epidemiological cohort study: describing service use

This population cohort study utilized a longitudinal database to define service use and current patterns of supportive and palliative care via a population cohort study of all incident hospitalized HGG cases in Victoria, Australia from January 2003 to July 2009. Analysis of nested subsets of this cohort using linked inpatient hospital, emergency, and death data enabled understanding of current health service utilization and investigation of factors associated with the receipt of palliative care, and quality indicators of end of life care.12,13 This study was approved by the Monash University Human Research Ethics Committee.

Data integration: developing recommendations for practice improvement

An advisory group was established to oversee all aspects of the program of work (Fig. 1). Experts with direct experience with HGG and providing care were invited to join the group, purposefully sampled from community and across a number of neuro-oncology treatment centers, with consumer representation in the form of 2 family caregivers (1 bereaved, 1 current carer), along with the disciplines of neurosurgery, radiation and medical oncology, psychiatry, social work, palliative care, nursing, general practice, health service evaluation, and policy. Members were invited according to discipline and site of care provision as well as known interest in the care of HGG patients. The advisory group and the study investigators provided input throughout the duration of the program of work, including methodological advice, clinical perspective, and interpretation of the results to develop a series of recommendations around a framework of supportive care.

This process of framework development based upon the substudies involved (i) determination of an underpinning agreed set of key principles to guide framework development (Table 1); (ii) articulation of core components of the framework, in line with the principles and designed to meet unmet needs; and (iii) service delivery activities which enact the principles and components of care.17

Table 1.

Development of principles and service components to underpin framework of care

| Principles guiding the framework of supportive and palliative care |

| 1. Care and services be aligned with patient/carer needs according to the transition point in the illness. 2. Care should provide continuous monitoring of patient/carer needs. 3. Care should be proactive in response to anticipated or expressed concerns. 4. Care should include routine bereavement support. 5. Care should include appropriate partnership and engagement of patients, carers, and families. |

| Framework components designed to meet needs and consistent with the principles |

| 1. Coordination 2. Repeated assessment 3. Staged information provision according to transition reached 4. Proactive responses and referral systems 5. Specific inquiry of patient’s and carer’s concerns |

Note. Developed based upon data from substudies.10–14 ,19

Consensus on the proposed framework of care was reached through a series of processes derived and adapted from 2011 Institute of Medicine Standards17 for developing rigorous, trustworthy, clinical practice guidelines. These processes included transparency around funding as well as disclosure of members’ conflicts of interest, multidisciplinary and methodological representation, clear elucidation and evaluation of the strength of the available evidence (in addition to using levels of evidence,20 rigor was also assessed using COREQ21 and STROBE22 standards for qualitative and epidemiological studies, respectively), and a standardized approach to recommendations reached, including the time points at which they should be enacted.

Results

A summary of the results of the substudies integrated with the framework principles and service components is presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

An integrated framework of palliative and supportive care for patients with HGG and their family caregivers

|

Principles underpinning

framework* |

1. Care and services be aligned with patient/family caregiver needs according to the transition point in the illness.

2. Care should provide continuous monitoring of patient/family caregiver needs. 3. Care should be proactive in response to anticipated or expressed concerns. 4. Care should include routine bereavement support. 5. Care should include appropriate partnership and engagement of patients and family caregivers. |

|

|

Transition 1:

Time of diagnosis of HGG |

Needs and gaps identified | • Shock and distress. • Focus on the immediate sense of always ‘waiting’ for something (treatment, scans, the next event). • Need for individualized written information about tumor (name, grade, site); patient information needs differ from family caregivers. • Importance of having a central, clearly identified contact person who is responsive, reliable, and available. • Valued health professional “checking in.” • Need for a consistent health professional to facilitate navigation between specialties and sites of care. |

| Framework and service components | • Coordination. - Introduce a nominated care coordinator to patients/families and central contact details provided. • Staged information provision according to transition reached. - Provides practical information for patients/families (ie, contact numbers, enlisting support, neuro-oncology roles, appointment dates), AND individualized tumor information (name, grade, site). • Repeated assessment. - Care coordinator undertakes proactive, routine regular telephone screening for needs and distress for patients/family caregivers. - Will involve a brief discussion of needs and screening for concerns. - Screening contacts will begin at diagnosis, and continue monthly. • Proactive and anticipatory responses. - Concerns identified will elicit responses including referral to appropriate services. • Specific inquiry of patient and family caregiver concerns. - Include family caregiver in care coordinator conversations as appropriate. |

|

| Transition 2: Conclusion of initial radiotherapy treatment | Needs and gaps identified | • Follow-up required after radiotherapy conclusion with hiatus in contact currently leading to sense of being unsupported. • Lack of understanding of personality/behavioral changes, with explanatory information very helpful. • The impact of behavioral and psychosocial issues is frequently not recognized (or acknowledged) by physicians. • Additional preparation, support, and acknowledgment for family caregiver’s role. • Currently health service responses are largely reactive to a crisis. Need for additional support for early intervention to avoid crisis situations and emergency department presentations. • Assess for additional allied health service provision. |

| Framework and service components | • Coordination. - Contact by care coordinator. • Staged information provision according to transition reached. - Written information detailing potential effects of brain tumors including according to site of tumor, eg, identifying and coping with executive impairments, impulsivity, perseveration. - Information regarding common concerns such as returning to work, seizures, and driving. • Repeated assessment. - Screening contacts by care coordinator continue monthly. • Proactive and anticipatory responses. - Emergent concerns identified; elicit responses. - Access to outpatient allied health as appropriate to screening outcomes, facilitating support with specific deficits identified. • Specific inquiry of patient and family caregiver concerns. - Encourage inclusion of family caregiver when providing information, in discussions and care planning. |

|

|

Transition 3:

Tumor recurrence |

Needs and gaps identified | • Uncertainty, functional deterioration, increasing dependence. • Loss of usual social support network, with both patient and family caregiver feeling isolated. • Balancing need to hope and with simultaneous need for information, preparation, support. • Increased family caregiver load, often unrecognized. • Family caregiver increasingly required to advocate for patient. • Determining best time for palliative care referral is difficult, particularly with need to maintain hope. |

| Framework and service components | • Coordination. - Contacted by care coordinator. • Staged information provision according to transition reached. - Information regarding supports available including palliative care, community supports for families, information about symptoms that commonly occur. • Repeated assessment. - Screening contacts by care coordinator continue, at minimum, monthly. • Proactive and anticipatory responses. - Routine referral to palliative care services enables integration, timely establishment of home supports, reduces crisis admissions, and further supports family caregivers. - Emergent concerns identified; elicit responses. - Access to outpatient allied health as appropriate to screening outcomes, facilitating support with specific deficits identified. • Specific inquiry of patient and family caregiver concerns. - Increasing emphasis upon collaborative approach whereby patients and family in care partnership with clinicians. - Discussion of availability of respite care for both patients and family caregiver. |

|

|

Transition 4:

Deterioration to death |

Needs and gaps identified | • Fear of being a burden to others; loneliness and complete dependence. • Dependence can continue for extended periods. • Family caregivers exhausted. • Inpatient palliative care services can offer comprehensive medical nursing and psychosocial support, but not resourced to provide long-term care. |

| Framework and service components | • Coordination. - Contacted by care coordinator, working increasingly in partnership with local support and palliative care services. • Staged information provision according to transition reached. - Information with focus on addressing expectations and concerns, and providing care at the end of life. • Repeated assessment. - Screening contacts by care coordinator continue. - Timing and frequency of these to coordinate with palliative care service delivery. Likely to be more frequent than previously. - Ongoing contact and “non-abandonment” important. • Proactive and anticipatory responses. - Readily available community based and inpatient respite service for patients and family caregivers. - Access to a step down palliative care unit, consisting of aspects of palliative care, notably more psychosocial services, and with less intensive specialized medical and nursing input for those requiring longer-term inpatient care. • Specific inquiry of patient and family concerns. - Ongoing inclusion and support of both patient and family caregivers. |

|

|

Transition 5:

After the patient’s death |

Needs and gaps identified | • Support for specific elements of the bereavement experience such as: o Sadness at missed opportunities due to early cognitive decline. o Regret that cause of behavioral changes misunderstood by family, who interpreted patient as being difficult. • Recognize the risk of complicated grief. • Coordinated bereavement support or follow-up. |

| Framework and service components | • Coordination. - Contacted by care coordinator following death. • Staged information provision according to transition reached. - Information about resources for bereaved people, useful practical information and potential contacts for support. • Repeated assessment at 6 and 12 months following patient death. - Contact at 6 and 12 months with screening for heightened bereavement distress. • Proactive and anticipatory responses. - Offer referral to bereavement services as appropriate. |

|

*Developed based upon data from substudies.10–14 ,19

Substudies 1: Defining Needs and Experiences—Substudy 1A: Systematic Review of Qualitative Literature

This review identified significant deficits in the areas of information availability particularly around specific outcomes of the disease itself, its treatment, and likely impact upon patients.19 The value of an identified key health professional to facilitate care coordination and clear paths of communication with professionals was highlighted (level IV evidence20).

Substudy 1B: Exploratory Interview Study

The patient cohort (N = 10) revealed immense losses associated with a change to their “former” selves, fears of impending deterioration, and the burden upon family associated with their care. Patients described the health system as having a narrow focus of “medical” care, with no time given to inquire about or acknowledge social, behavioral, or existential concerns.11

The family caregiver cohort (N = 22) revealed the enormity of the caring role, which had many challenges, particularly for those dealing with behavioral changes in their loved one, the person with HGG.14 A lack of patient insight into such changes and a health system focus on only patients’ needs meant family caregivers felt their own needs were often not addressed. At the same time, they were responsible for difficult decisions about the patient’s treatment and care, frequently without the perceived appropriate level of information required. A number of gaps in the current provision of care were raised, including a lack of care coordination and continuity, a need for individualized information, anticipation of and preparation for emerging problems, and emotional support. Care was reported to be ad hoc and inconsistent, with some family caregivers noting more positive experiences of the health system following connection with a particular individual who assisted them to navigate the systems of care.

The HCPs (N = 35) noted the difference in the HGG illness course compared with other cancers.10 The unique HGG illness trajectory is characterized by acute, unexpected, and devastating deterioration of function often at diagnosis with early cognitive decline, physical disability, and behavioral changes.10 The process of dying was reported to be prolonged, with patients suffering substantial physical and cognitive morbidity for, often, long periods prior to death, resulting in a prolonged intensive family caregiving role. Specific inquiry around behavioral, social, or psychological sequelae was frequently not undertaken and family input not routinely sought. Care was concentrated around large hospital centers and tended to involve episodes of time-intensive treatment such as radiotherapy and surgery. These episodes were then punctuated by long periods of “surveillance” where care was primarily based in the community with intermittent contact by the centralized unit. Palliative care inpatient services reported constraints in being able to provide longer-term care to people who may have physical morbidity and need care for months. They therefore screened patients carefully prior to admission (level IV evidence).20

Substudy 2: Defining Patterns of Care

Patients in the cohort study of all incident cases of HGG in Victoria, Australia (N = 1821), including only those people who had diagnoses and died in the study period, had an overall median survival of 11 months.12 For 25%, death occurred in an acute hospital bed, another quarter (26%) died outside hospital, including at home, and the remainder (49%) died in an inpatient palliative care bed. Between diagnosis and death, patients had a median of 4 hospital admissions with an overall median length of stay of 43 days. Patients with a high burden of symptoms are more likely to receive palliative care, and in turn patients who received palliative care were 1.7 times more likely to die outside of hospital.12

For the subgroup of patients (n = 482) with short survival (<120 days), just 12% (32/264) of those discharged from hospital were referred to palliative care services13 (level IIb evidence).20

Recommendations for a Framework of Supportive and Palliative Care

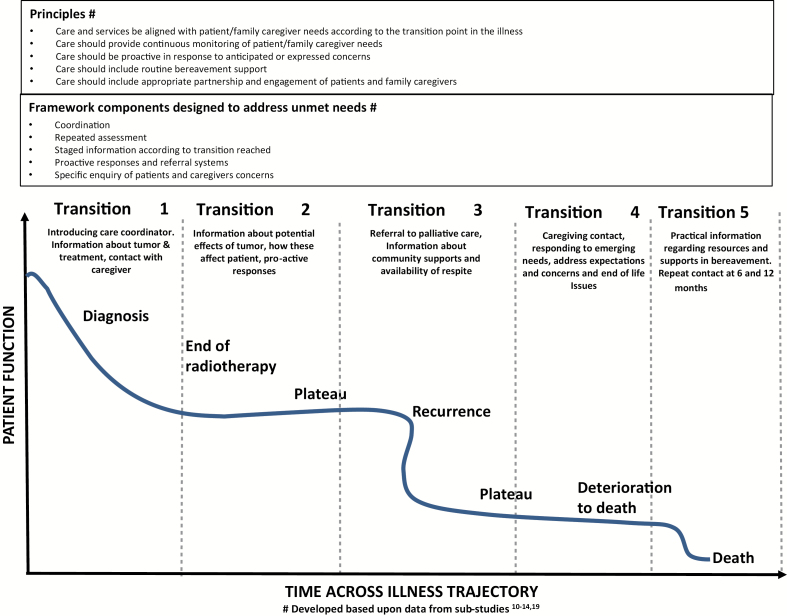

Using the illness trajectory articulated in the substudies, transition points were identified which present opportunities to intervene and improve services.10 These key transition points include: at time of diagnosis of HGG, end of initial radiotherapy treatment, time of tumor recurrence, deterioration to death, and following death. The overview of the illness trajectory populated with responses according to these transitions is presented (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Service responses based upon transitions in the HGG illness trajectory.

A series of key principles were developed based upon the substudies and underpinning the framework of care. These principles were informed by and adapted from the Crossing the Quality Chasm report.17,23 The components of the framework aligned with these principles and designed to address unmet needs are presented in Table 1. Detailed descriptions of how the principles and framework components demonstrate responsiveness to identified needs are presented at each of the transition points: diagnosis, end of initial radiotherapy treatment, tumor recurrence, deterioration to death, and following death (Table 2, Fig. 2).

Discussion

The proposed framework of supportive and palliative care is, to our knowledge, the first comprehensive approach to supportive and palliative care that is directly based upon identified needs and encompasses care at the end of life. Furthermore it uniquely seeks to detail specific responses according to the stage of illness reached. This framework builds upon guidelines detailing care and symptom relief for this patient group.24 There are several important core concepts within this framework which should be highlighted.

Firstly, the key principles, the HGG illness trajectory and its attendant transition points which form the basis of the framework, are not tied to particular times but rather to stages of the illness reached, such as conclusion of initial radiotherapy treatment or time of first recurrence. This means that the framework of care may be relevant for those patients who have poor prognostic features and short survival, but equally for those who live many months or years. Other authors have identified the high levels of distress and unmet needs of patients and their family caregivers across a number of illness points.25–27 The proposed framework enables HCPs to recognize the stage of the illness and the transition points of change and to respond according to the needs that arise with each of these transition points, not upon time.

Second, the framework ensures standardization of care, since the reaching of a transition point in the illness trajectory means that a response should ensue as a matter of routine. Such a response may be the routine provision of information, a referral to palliative care, or an offer of bereavement support according to the transition point reached. For example, at diagnosis, basic practical information should be provided to patients or carers, such as important contact numbers, how to enlist support, explanation of neuro-oncology roles, individualized tumor information, appointment dates, and medication register. Walbert and colleagues have noted that a third of neuro-oncology clinicians feel uncomfortable referring to palliative care, and more than half suggest a name change would be useful,28 suggesting that individual practice may vary and hinder routine early palliative care integration.29,30 The proposed linking of illness transition points with specific responses means that care is no longer dependent upon individual clinicians, with variance from the recommendations needing to be justified, and equitable supportive and palliative care more likely to be available to all.

Third, the framework of care should be structured with a central coordinating figure, who will be introduced around the time of diagnosis, make regular contact, screen for distress, and provide information proactively. This regular contact and conversation facilitates the development of a relationship and trust between patients and family caregivers. It is suggested that regular contact and screening for needs should be introduced following diagnosis. At minimum, monthly contact is also suggested until a specified time, such as 12 months, following diagnosis and thereafter occur at an interval determined in collaboration with the patient and carer. Patient or carer needs identified through screening will prompt an appropriate response such as additional information, or offered referral to relevant services, enabling services to be proactive in care. It is anticipated that the relationship established through regular contact will facilitate patients to spontaneously alert the care coordinator of emerging concerns between scheduled contact times. In addition to information according to identified needs, routine information should also be provided relevant to the illness transition reached. This enables information provision to be tailored according to the stage of illness—a need highlighted by patients and carers.

It is anticipated that the identified care coordinator, and the access to information according to current needs and stage of illness, will enhance support of patients and their carers and facilitate their participation in decision making around care.31 Furthermore the relationship forged with the care coordinator might facilitate other components of care which may not have been previously accessed, such as early engagement with palliative care services or bereavement services. In this way the care coordinator, based in the neuro-oncology center, not only supports the patient and caregiver, but may also provide support to those local services, including palliative care, in responding to the specialized needs of HGG patients with complex needs. The care coordinator figure is the key role to ensure that supportive and palliative care is delivered in a timely and effective way. In Australia, this role is typically filled by an advanced practice nurse experienced in neuro-oncology care, but in other health care systems the tasks may be better enacted by other clinicians.

Finally, the framework specifies clear pathways for referral to specialist palliative care services for patients with HGG with referral, at minimum, at time of first recurrence of cancer after initial therapy. It may be that palliative care referral is considered earlier than this time, but if not, it should occur at first recurrence. Most providers would consider palliative care referral only when symptoms require it, and not on a routine basis.28 A standardization of referral processes means greater equity with the full benefits of palliative care made available to all. All patients should be given the opportunity to understand the aspects of palliative care that may be relevant to their circumstances, and make decisions accordingly. The degree of engagement thereafter can then be negotiated between patient and services according to needs.

While this framework was developed in Australia and based upon needs identified by Australian patients, families, and clinicians, we believe that the concepts underpinning this framework have relevance internationally. The HGG illness trajectory with attendant transitions that unfold over the illness course and the recommended responses according to these transitions have international resonance. These are responses based upon change and need, not upon time. Also of international relevance is the need for proactive responses to problems as they begin to emerge rather than reactive responses once the problem is established with possibly already irreversible consequences—for example, upon the family caregiver’s confidence. Finally, the inclusion of the family caregiver as an acknowledged and critical part of the care relationship is important worldwide.32

As such, we suggest that this framework of supportive and palliative care for patients with HGG represents an important step in highlighting, in detail, the needs of this important cancer group, who, despite treatment advances, continue to have poor prognostic disease. A framework which is staged based upon commonly recognized illness transitions and includes family caregivers ensures its transferability nationally and internationally. Future research examining the implementation and impact of this framework forms the next phase of work.

Funding

This work was supported by the Victorian Cancer Agency, Department of Health, Victoria, Australia.

Conflict of interest statement. No conflicts of interest are declared by the authors in relation to this work.

References

- 1. Dolecek TA, Propp JM, Stroup NE, Kruchko C. CBTRUS statistical report: primary brain and central nervous system tumors diagnosed in the United States in 2005–2009. Neuro Oncol. 2012;14(Suppl 5):v1–49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Cancer Council Victoria. http://www.cancervic.org.au/downloads/cec/cancer-in-vic/Cancer-in-Victoria_Statistics-Trends_2015.pdf. 20152017.

- 3. Louis DN, Ohgaki H, Wiestler OD et al. The 2007 WHO classification of tumours of the central nervous system. Acta Neuropathol. 2007;114(2):97–109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Weller M, van den Bent M, Hopkins K et al. ; European Association for Neuro-Oncology (EANO) Task Force on Malignant Glioma. EANO guideline for the diagnosis and treatment of anaplastic gliomas and glioblastoma. Lancet Oncol. 2014;15(9):e395–e403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Stupp R, Mason WP, van den Bent MJ et al. ; European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer Brain Tumor and Radiotherapy Groups; National Cancer Institute of Canada Clinical Trials Group Radiotherapy plus concomitant and adjuvant temozolomide for glioblastoma. N Engl J Med. 2005;352(10):987–996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Bauchet L, Mathieu-Daudé H, Fabbro-Peray P et al. ; Société Française de Neurochirurgie (SFNC); Club de Neuro-Oncologie of the Société Française de Neurochirurgie (CNO-SFNC); Société Française de Neuropathologie (SFNP); Association des Neuro-Oncologues d’Expression Française (ANOCEF) Oncological patterns of care and outcome for 952 patients with newly diagnosed glioblastoma in 2004. Neuro Oncol. 2010;12(7):725–735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Yabroff KR, Harlan L, Zeruto C, Abrams J, Mann B. Patterns of care and survival for patients with glioblastoma multiforme diagnosed during 2006. Neuro Oncol. 2012;14(3):351–359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Stupp R, Brada M, van den Bent MJ, Tonn JC, Pentheroudakis G; ESMO Guidelines Working Group High-grade glioma: ESMO clinical practice guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2014;25(Suppl 3):iii93–ii101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Cancer Australia. https://www.cancer.org.au/content/ocp/health/optimal-cancer-care-pathway-for-people-with-high-grade-glioma-june-2016.pdf, 2016.

- 10. Philip J, Collins A, Brand CA et al. Health care professionals’ perspectives of living and dying with primary malignant glioma: implications for a unique cancer trajectory. Palliat Support Care. 2015;13(6):1519–1527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Philip J, Collins A, Brand CA et al. “I’m just waiting . . .”: an exploration of the experience of living and dying with primary malignant glioma. Support Care Cancer. 2014;22(2):389–397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Sundararajan V, Bohensky MA, Moore G et al. Mapping the patterns of care, the receipt of palliative care and the site of death for patients with malignant glioma. J Neurooncol. 2014;116(1):119–126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Collins A, Sundararajan V, Brand CA et al. Clinical presentation and patterns of care for short-term survivors of malignant glioma. J Neurooncol. 2014;119(2):333–341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Collins A, Lethborg C, Brand C et al. The challenges and suffering of caring for people with primary malignant glioma: qualitative perspectives on improving current supportive and palliative care practices. BMJ Support Palliat Care. 2014;4(1):68–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Council MR. www.mrc.ac.uk/complexinterventionsguidance, 2006.

- 16. Östlund U, Kidd L, Wengström Y, Rowa-Dewar N. Combining qualitative and quantitative research within mixed method research designs: a methodological review. Int J Nurs Stud. 2011;48(3):369–383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Institute of Medicine. Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2001. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Sundararajan V, Bohensky M, Moore G et al. Utilising hospital administrative datasets to identify patterns of service use in patients with a primary malignant glioma. Palliat Med. 2012;26(4):521. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Moore G, Collins A, Brand C et al. Palliative and supportive care needs of patients with high-grade glioma and their carers: a systematic review of qualitative literature. Patient Educ Couns. 2013;91(2):141–153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Oxford Centre Evidence Based Medicine. http://www.cebm.net/oxford-centre-evidence-based-medicine-levels-evidence-march-2009/, 2009.

- 21. Tong A, Sainsbury P, Craig J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int J Qual Health Care. 2007;19(6):349–357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, Pocock SJ, Gøtzsche PC, Vandenbroucke JP; STROBE Initiative The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. J Clin Epidemiol. 2008;61(4):344–349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Institute of Medicine. Clinical Practice Guidelines We Can Trust. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Pace A, Dirven L, Koekkoek JAF et al. ; European Association of Neuro-Oncology palliative care task force European Association for Neuro-Oncology (EANO) guidelines for palliative care in adults with glioma. Lancet Oncol. 2017;18(6):e330–e340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Halkett GK, Lobb EA, Oldham L, Nowak AK. The information and support needs of patients diagnosed with high grade glioma. Patient Educ Couns. 2010;79(1):112–119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Halkett GK, Lobb EA, Shaw T et al. Distress and psychological morbidity do not reduce over time in carers of patients with high-grade glioma. Support Care Cancer. 2017;25(3):887–893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Kvale EA, Murthy R, Taylor R, Lee JY, Nabors LB. Distress and quality of life in primary high-grade brain tumor patients. Support Care Cancer. 2009;17(7):793–799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Walbert T, Glantz M, Schultz L, Puduvalli VK. Impact of provider level, training and gender on the utilization of palliative care and hospice in neuro-oncology: a North-American survey. J Neurooncol. 2016;126(2):337–345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Walbert T, Pace A. End-of-life care in patients with primary malignant brain tumors: early is better. Neuro Oncol. 2016;18(1):7–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Walbert T. Integration of palliative care into the neuro-oncology practice: patterns in the United States. Neurooncol Pract. 2014;1(1):3–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence(NICE). Improving Outcomes for People with Brain and Other CNS Tumours. London, UK: NICE; 2006. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/csg10/resources/improving-outcomes -for-people-with-brain-and-other-central-nervous-system-tumours-update-27841361437 [Google Scholar]

- 32. Hudson P, Aranda S. The Melbourne Family Support Program: evidence-based strategies that prepare family caregivers for supporting palliative care patients. BMJ Support Palliat Care. 2014;4(3):231–237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]