Abstract

Background:

Neuroimaging studies have used magnetic resonance imaging-derived methods to assess brain volume loss in multiple sclerosis (MS) as a reliable measure of diffuse tissue damage.

Methods:

In the CLARITY study (ClinicalTrials.gov NCT00213135), the effect of 2 years’ treatment with cladribine tablets on annualized percentage brain volume change (PBVC/y) was evaluated in patients with relapsing MS (RMS).

Results:

Compared with placebo (–0.70% ± 0.79), PBVC/y was reduced in patients treated with cladribine tablets 3.5 mg/kg (–0.56% ± 0.68, p = 0.010) and 5.25 mg/kg (–0.57% ± 0.72, p = 0.019). After adjusting for treatment group, PBVC/y showed a significant correlation with the cumulative probability of disability progression (HR = 0.67, 95% CI = 0.571, 0.787; p < 0.001), with patients with lower PBVC/y showing the highest probability of remaining free from disability progression at 2 years and vice versa.

Conclusions:

Cladribine tablets given annually for 2 years in short-duration courses in patients with RMS in the CLARITY study significantly reduced brain atrophy in comparison with placebo treatment, with residual rates in treated patients being close to the physiological rates.

Keywords: Brain atrophy, brain volume, cladribine, CLARITY, disease progression, relapsing multiple sclerosis

Introduction

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is an inflammatory, demyelinating condition that affects the central nervous system and is associated with progressive disability progression. Although the pathological hallmark of MS is represented by the focal demyelinating lesions, there is compelling evidence suggesting that focal demyelinating lesions are only one part of MS pathology and that diffuse tissue damage also occurs throughout the whole central nervous system.1 This is mostly driven by a constant and relentless neurodegeneration leading to the accumulation of brain atrophy.2

Neuroimaging studies have used magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)-derived methods to assess brain volume loss (BVL) in MS as a reliable measure of diffuse tissue damage.3 They have shown that BVL occurs since the earliest stages of MS, accumulates throughout the course of MS, and appears to be correlated with physical disability and cognitive impairment.3 In addition, some recent studies have shown that BVL can be reduced in patients with relapsing multiple sclerosis (RMS) under specific pharmacological treatments.3

Against this background, we performed an exploratory analysis on the CLAdRIbine Tablets treating multiple sclerosis orallY (CLARITY) study. This was a phase-3, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicenter trial in patients with RMS assessing the effects of cladribine tablets given annually over 2 years, with each annual treatment course consisting of 2 treatment weeks.4 We evaluated the effect of cladribine tablets on BVL over 2 years in RMS patients and the association of BVL with confirmed disability progression.

Materials and methods

Details of the CLARITY study (ClinicalTrials.gov NCT00213135) have been previously published.4 Briefly, patients with RMS were randomized 1:1:1 to receive cladribine tablets 3.5 or 5.25 mg/kg of body weight or matching placebo for 2 years. MRI scans were obtained at the pre-study evaluation and after 6, 12, and 24 months. For the exploratory analysis performed here, BV measurements were performed on pre-gadolinium T1-weighted MRI scans, which reached adequate quality control procedures, by means of the Structural Image Evaluation using Normalization of Atrophy (SIENA) software.5 Data between months 0 and 6 were excluded from the calculation to avoid any potentially confounding influence of the paradoxical acceleration of BVL following the initiation of an anti-inflammatory therapy, referred to as pseudoatrophy.6 Percentage of brain volume changes (PBVC) between months 6 and 24 was compared among treatment arms by an analysis of variance model. Data were also expressed as annualized PBVC (PBVC/year) and calculated between months 6 and 24. The correlation between rates of PBVC/year and the risk of 3-month confirmed Expanded Disability Status Scale (EDSS)7 progression was analyzed by a Cox proportional hazard model, after adjusting for treatment effect.

Results

Demographic and clinical details of the 1326 patients with RMS included in the original study have been described previously.4 In this study, 1025 (77.3%) patients could be included in the BV exploratory analysis (cladribine tablets 3.5 mg/kg, n = 336; cladribine tablets 5.25 mg/kg, n = 351; placebo, n = 338). Data of 301 patients were not included in the study due to missing or inadequate acquisition of the pre-gadolinium T1-weighted MRI scans at one or more time-points (see Table 1 for demographic and clinical details of patients included and not included in the analysis).

Table 1.

Baseline demographics and clinical characteristics of patients included and not included in the analysis.

| Variable | Patients included in the analysis (n = 1025) | Patients not included in the analysis (n = 301) |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | ||

| Mean | 38.7 ± 10.0 | 38.3 ± 10.0 |

| Range | 18−65 | 18−62 |

| Female gender (no. (%)) | 699 (68.2) | 199 (66.1) |

| Disease duration from onset (years) | ||

| Mean | 8.7 ± 7.4 | 8.5 ± 7.5 |

| Range | 0.3−42.3 | 0.4−37.1 |

| EDSS score (no. (%)) | ||

| 0 | 28 (2.7) | 8 (2.7) |

| 1 | 175 (17.1) | 50 (16.6) |

| 2 | 301 (29.4) | 78 (25.9) |

| 3 | 236 (23.0) | 76 (25.2) |

| 4 | 190 (18.5) | 48 (15.9) |

| ⩾5 | 95 (9.3) | 41 (13.6) |

| Mean | 2.9 ± 1.3 | 3.0 ± 1.3 |

| Patients previously treated with any disease-modifying drug (no. (%)) | 286 (27.9) | 116 (38.5) |

| Gadolinium-enhancing T1-weighted lesions | ||

| Patients with Gd+ activity (no. (%)) | 330 (32.2) | 83 (27.6) |

| Mean number of lesions | 1.0 ± 2.5 | 0.7 ± 1.9 |

| Mean volume of lesions (mm3) | 196.4 ± 589.3 | 134.0 ± 395.3 |

| Mean volume of T2-weighted lesions (mm3) | 15,912.2 ± 16,319.3 | 13,947.9 ± 13,731.4 |

SD: standard deviation; EDSS: Expanded Disability Status Scale.

No significant between-group differences were seen for all variables, except the proportion of patients who had received previous treatment with a disease-modifying drug (p = 0.0002). Plus–minus values indicate SD.

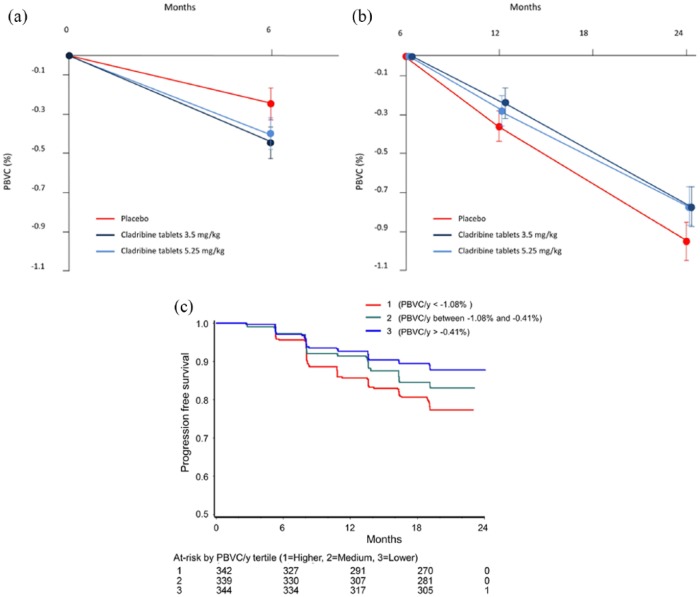

The mean PBVC was assessed from months 6 to 24 to avoid confounding influence of pseudoatrophy in the first 6 months (see section “Materials and methods” and Figure 1(a)). This was significantly reduced in patients treated with cladribine tablets 3.5 mg/kg (−0.77% ± 0.94%, p = 0.02, n = 336) and 5.25 mg/kg (−0.77% ± 0.95%, p = 0.02, n = 351) compared with those treated with placebo (−0.95% ± 1.06%, n = 338; Figure 1(b)).

Figure 1.

Effect of treatment on (a) mean PBVC for months 0–6, (b) mean PBVC for months 6–24, and (c) rate of disability-progression-free survival in PBVC/year tertiles in the CLARITY study.

When the subgroup of patients who presented with gadolinium-enhancing lesions at baseline was assessed, PBVC from months 6 to 24 was not different between the three patient arms (cladribine 3.5 mg/kg: −0.92% ± 1.02%, n = 110; cladribine 5.25 mg/kg: −1.00% ± 1.08%, n = 115; placebo: −0.97% ± 0.97%, n = 106).

When data from the whole group of patients were annualized, the mean PBVC/year (months 6–24) was also significantly reduced in patients treated with cladribine tablets 3.5 mg/kg (−0.56% ± 0.68%, p = 0.010, n = 336) and 5.25 mg/kg (−0.57% ± 0.72%, p = 0.019, n = 351) compared with patients treated with placebo (−0.70% ± 0.79%, n = 338).

The risk of disability progression was significantly lower in patients treated with cladribine tablets 3.5 mg/kg (hazard ratio (HR) = 0.63, 95% confidence interval (CI) = 0.438, 0.894; p = 0.010) and 5.25 mg/kg (HR = 0.58, 95% CI = 0.406, 0.833; p = 0.003) than in those treated with placebo. After adjusting for treatment group, PBVC/year showed a significant correlation with the cumulative probability of disability progression in the overall study population (HR = 0.67, 95% CI = 0.571, 0.787; p < 0.001). By sub-dividing patients into PBVC/year tertiles, the tertile with the lowest BVL (PBVC/year > −0.4%) showed the highest rate of patients free from disability progression at 24 months (89%), and the tertile with the greatest BVL (PBVC/year < −1.08%) showed the lowest rate of patients free from disability progression (79%; Figure 1(c)).

Discussion

In the CLARITY study, patients treated with cladribine tablets showed significantly less annualized brain atrophy over 2 years than patients receiving placebo. This is in line with other RMS trials that have also shown significant BV reductions with disease-modifying therapies3 and provides further evidence of the need for treatments that target not only focal inflammation but also the diffuse brain tissue damage and neurodegeneration that occur over the course of MS.

Since anti-inflammatory drugs used for the treatment of MS have often been associated with a paradoxical acceleration of BVL following the initiation of therapy (i.e. pseudoatrophy),6 we excluded here PBVC data from the first 6 months of the study. Indeed, PBVC data clearly showed a pronounced pseudoatrophy effect after therapy initiation. In line with this, no treatment effect on PBVC was shown in the subgroup of patients who presented with gadolinium-enhancing lesions at baseline, a finding similar to that reported in MS patients treated with other anti-inflammatory agents.8 In this context, it must be stressed that the assumption that pseudoatrophy occurs only during the first months of therapy is not necessarily valid, as the time course of pseudoatrophy is not completely understood.6 Indeed, there is the possibility that the accelerated BVL associated with the suppression of inflammation can continue even beyond 1 year.6 This may explain the relatively small treatment effect found in our study, suggesting that the neuroprotective effect of cladribine, as reflected by slowing of BVL between months 6 and 24, is still being underestimated and that the 2-year placebo-controlled observation period might not be long enough to fully evaluate this effect.

In this study, we also assessed PBVC/year rates to be able to compare them to previously reported data.9 Both treatment arms of this study (0.56% and 0.57% for 3.5 and 5.25 mg/kg, respectively) were comparable to the PBVC/year rate (0.52%) reported in a recent longitudinal analysis of MRI data which used identical methodology (i.e., SIENA) and provided a 95% specificity in discriminating patients with MS from healthy controls and to have a prognostic value for discriminating patients who would develop disability progression in a long-term follow-up.9

Another important finding of this exploratory analysis is the close correlation between PBVC/year and disability progression, with the highest probability of remaining free from disability progression observed in patients who showed the least brain atrophy and vice versa. These findings also add to what is known about the benefits of cladribine tablets treatment seen in clinical trials: the risk of disability progression was significantly lower in the two groups treated with cladribine tablets compared with placebo.4 The results of the present analysis suggest that the benefits of cladribine tablets in RMS patients may include significant reduction in the neurodegeneration associated with MS clinical progression.

We therefore conclude that cladribine tablets given annually for 2 years in short-duration courses in patients with RMS in the CLARITY study significantly reduced brain atrophy in comparison with placebo treatment, with residual rates in treated patients being close to the physiological rates. Furthermore, the brain atrophy reduction was closely associated with a lower risk of disability progression, suggesting that, in addition to the effects on focal demyelination,4 treatment with cladribine tablets can target diffuse brain tissue damage and neurodegeneration in patients with RMS.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank patients and their families, investigators, coinvestigators, and the study teams at each of the participating centers and at Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared the following potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: N.D.S. has received honoraria from Schering, Biogen Idec, Teva Pharmaceutical Industries Ltd, Novartis, Genzyme Corporation, Roche, and Merck for consulting services, speaking, and travel support. He serves on advisory boards for Biogen Idec, Merck, Novartis, Genzyme Corporation, and Roche. He has received research grant support from the Italian MS Society. A.G. has no conflicts of interest to declare. M.B. has no conflicts of interest to declare. A.D.L. has no conflicts of interest to declare. C.H. is an employee of Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany. F.D. is an employee of EMD Serono, Inc, Billerica, MA, USA, a business of Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany. G.G. serves on advisory boards for Merck, Biogen Idec, and Vertex Pharmaceuticals; has received speaker honoraria and consulting fees from Bayer Schering Pharma, FivePrime, GlaxoSmithKline, GW Pharmaceuticals, Merck, Biogen Idec, Pfizer Inc, Protein Discovery Laboratories, Teva Pharmaceutical Industries Ltd, Sanofi-Aventis, UCB, Vertex Pharmaceuticals, Genzyme Corporation, Ironwood, and Novartis; serves on the Merck speakers bureau; and received research support unrelated to this study from Biogen Idec, Merck, Novartis, and Ironwood. M.P.S. has received personal compensation for consulting services and for speaking activities from Genzyme Corporation, Merck, Teva Pharmaceutical Industries Ltd, Synthon, Actelion, Novartis, and Biogen Idec.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This study was supported by ARES Trading SA, Aubonne, Switzerland, a business of Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany. Medical writing support was provided by Phil Jones of inScience Communications, Springer Healthcare (Chester, UK) and was funded by Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany.

Contributor Information

Nicola De Stefano, Department of Medicine, Surgery and Neuroscience, University of Siena, Siena, Italy.

Antonio Giorgio, Department of Medicine, Surgery and Neuroscience, University of Siena, Siena, Italy.

Marco Battaglini, Department of Medicine, Surgery and Neuroscience, University of Siena, Siena, Italy.

Alessandro De Leucio, Department of Medicine, Surgery and Neuroscience, University of Siena, Siena, Italy.

Christine Hicking, Global Biostatistics, Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany.

Fernando Dangond, Global Clinical Development, EMD Serono, Inc., Billerica, MA, USA.

Gavin Giovannoni, Department of Neurology, Blizard Institute, Barts and The London School of Medicine and Dentistry, Queen Mary University of London, London, UK.

Maria Pia Sormani, Biostatistics Unit, Department of Health Sciences, University of Genoa, Genoa, Italy.

References

- 1. Filippi M, Rocca MA, Barkhof F, et al. Association between pathological and MRI findings in multiple sclerosis. Lancet Neurol 2012; 11: 349–360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Matthews PM, Roncaroli F, Waldman A, et al. A practical review of the neuropathology and neuroimaging of multiple sclerosis. Pract Neurol 2016; 16: 279–287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. De Stefano N, Airas L, Grigoriadis N, et al. Clinical relevance of brain volume measures in multiple sclerosis. CNS Drugs 2014; 28: 147–156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Giovannoni G, Comi G, Cook S, et al. A placebo-controlled trial of oral cladribine for relapsing multiple sclerosis. N Engl J Med 2010; 362: 416–426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Smith SM, Zhang Y, Jenkinson M, et al. Accurate, robust, and automated longitudinal and cross-sectional brain change analysis. Neuroimage 2002; 17: 479–489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. De Stefano N, Arnold DL. Towards a better understanding of pseudoatrophy in the brain of multiple sclerosis patients. Mult Scler 2015; 21: 675–676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Kurtzke JF. Rating neurologic impairment in multiple sclerosis: An expanded disability status scale (EDSS). Neurology 1983; 33: 1444–1452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Sastre-Garriga J, Tur C, Pareto D, et al. Brain atrophy in natalizumab-treated patients: A 3-year follow-up. Mult Scler 2015; 21: 749–756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. De Stefano N, Stromillo ML, Giorgio A, et al. Establishing pathological cut-offs of brain atrophy rates in multiple sclerosis. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2016; 87: 93–99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]