Abstract

Traditional Australian Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander societies value men’s role as parents; however, the importance of promoting fatherhood as a key social determinant of men’s well-being has not been fully appreciated in Western medicine. To strengthen the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander male parenting role, it is vital to examine current barriers and opportunities. The first author (a male Aboriginal health project officer) conducted yarning sessions in three remote Australian communities, two being Aboriginal, the other having a high Aboriginal population. An expert sample of 25 Aboriginal and 6 non-Aboriginal stakeholders, including maternal and child health workers and men’s group facilitators, considered barriers and opportunities to improve men’s parenting knowledge and role, with an aim to inform services and practices intended to support men’s parenting. A specific aim was to shape an existing men’s group program known as Strong Fathers, Strong Families. A thematic analysis of data from the project identified barriers and opportunities to support men’s role as parents. Challenges included the transition from traditional to contemporary parenting practices and low level of cultural and male gender sensitivity in maternal and child health services. Services need to better understand and focus on men’s psychological empowerment and to address shame and lack of confidence around parenting. Poor literacy and numeracy are viewed as contributing to disempowerment. Communities need to champion Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander male father role models. Biases and barriers should be addressed to improve service delivery and better enable men to become empowered and confident fathers.

Keywords: aboriginal and torres strait islander, male parents, men’s health

Evidence suggests that Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander men’s health and well-being may benefit from strengthening their role as parents (Adams, 2006; Tsey et al., 2004). Further, men’s parenting can improve child development and family harmony in low-income and Indigenous societies (Bornstein, 2012; Opondo et al., 2016; Panter-Brick et al., 2014). The Strong Fathers, Strong Families (SFSF) program, conducted in a men’s group format, incorporates the broad aim of promoting men’s well-being by emphasizing the value of their role as proud Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander fathers, grandfathers, and uncles (McCalman et al., 2006a; McCalman et al., 2006b). Participating men are encouraged to see themselves as healthy role models for their children and to provide positive support to their partners, particularly in the antenatal and postnatal periods (Strong Fathers, Strong Families Funding Guideline, 2011).

To strengthen the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander male parenting role, it is vital to examine current barriers and opportunities for their engagement with the relevant health and welfare services in remote Aboriginal communities. This paper is informed by data from yarning sessions, which are an Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander method for sharing experiences and knowledge (Geia, Hayes, & Usher, 2013). Yarning sessions were conducted systematically with Aboriginal community stakeholders (Bessarab & Ng’andu, 2010; Geia, Hayes, & Usher, 2013) to gather knowledge about the opportunities and barriers to men’s parenting in the context of service delivery. The aim was to inform the SFSF program, Aboriginal health policy and practice related to child and maternal health, and the Aboriginal men’s health field.

Strong Fathers, Strong Families

The SFSF program is funded by the Australian Federal Government Department of Health and Ageing. The funding was distributed to 13 organizations nationally, with the Royal Flying Doctor Service (RFDS) Queensland Section being one of the funded organizations. The SFSF program broadly aims to build genuine, sensitive, trusting, and culturally appropriate relationships with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander males and the wider community. For brevity, the endorsed term Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander is interchangeably referred to as Aboriginal or Indigenous in this article. The broad objective of SFSF is to recognize and support the important influence that fathers, uncles, and grandfathers have in the lives of children, mothers, and families. The specific objectives of SFSF are to engage Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander men using a men’s group method to increase knowledge and access to culturally appropriate antenatal, early childhood development, and parenting services (McCalman et al., 2006b). The men’s groups also function as referral sites to other health providers in the communities. The SFSF program was implemented by RFDS in three remote area Lower Gulf communities, Normanton, Mornington Island, and Doomadgee (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Map of Lower Gulf of Carpentaria communities.

Historical Parenting Roles Among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Men

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander men’s parenting requires an understanding of contextual factors including colonization, discrimination, and bias in government policy. Compromised health including mental health and an increased risk of suicide have been associated with an undermined male role in Indigenous society (Adams & Danks, 2007). The denial of the male role and responsibility has been connected with living less meaningful and healthy lifestyles and with poor psychological and physical health status relative to that of non-Indigenous men (Marmot, 2011). Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander men have a life expectancy of approximately 59 years, which is 17 years less than that of non-Indigenous men. The mortality rate for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander men is in fact three to seven times higher than for non-Indigenous men in the same age group, with the main causes being cardiovascular diseases, injury, respiratory diseases, and diabetes (Hayman, 2010).

To understand the historical and contemporary role that men play within Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander families, it is necessary to reflect on Australian history. Before British settlement in 1788—or from a critical perspective, before the conquest—Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders lived in a complex democratic society with a diversity of roles and relationships (Rowe & Tuck, 2017). These roles and relationships defined connectedness to every other person in the group and determined the behavior of an individual to each person (Purdie, Dudgeon, & Walker, 2010). Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander kinship systems determined particular rules of commitment, obligation, and entitlement in the family and in the wider community (Furber-Gillick, 2011). The intricate kinship system placed importance on relationships and the family unit, including the rearing of young children by the women. An important component of kinship was the initiation of young males, who were understood to have reached adolescence following their ritual removal from the family unit by senior male leaders so that they could participate in ceremonies. These initiation ceremonies, which have also been known as the Bora Ring, symbolize the shift from being a boy to becoming an adult male (McIntyre-Tamwoy, 2008).

Traditional Aboriginal kinship systems had clearly defined responsibilities and obligations for women and for men, such as parenting, ceremonies, and access to food (Hamilton, 1980). Traditional gendered roles, relationships, and responsibilities have however been threatened and undermined by contemporary Australian society. In particular, modernization has challenged Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander male roles, authority, and status (Bulman, 2009). Since colonization, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people have experienced systemic racism and discrimination. This has included unfair and damaging legislation, acts of murder, denial of essential foods, removal from traditional lands, inhumane treatment, rape, and other acts of physical violence. Aboriginal children who were considered “part White” or “half caste” were taken from their families so that they could be “civilized” under a devastating policy of racial assimilation. As many as 1 in 10 Indigenous children were forcibly removed from their families and communities in the first half of the 20th century (Dudgeon et al., 2010). The historical and, in some cases, contemporary removal of Aboriginal children from their families has significantly undermined the confidence of parents, including the male fatherhood role. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children raised in non-Indigenous homes lacked culturally appropriate role models, and therefore raised their own children without the benefit of cultural continuity in knowledge. In traditional Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander societies, young men had a clear passage to manhood. However, racial oppression and the dislocation and dispossession of Aboriginal people has disrupted these traditional practices, denying young males the pathway and rituals to signify their development into men (Reilly, 2008). In addition, the forced relocation of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people to missions and settlements restricted men from performing their traditional roles as landowners, educators, father figures, providers, and decision makers. The historical treatment of Aboriginal people has been described as a process of breaking their spirit and connection to the land and the family (Lowe & Spry, 2002).

Fatherhood Research

Health research and policy on fatherhood is almost nonexistent when compared with the wealth of studies concerning maternal health (Bartlett, 2004). A global review of literature reported that men are marginal to the bulk of parenting interventions (Panter-Brick et al., 2014). Most research concerning men as parents focuses on health and development outcomes for children (Opondo et al., 2016) or their female partners (Bond, 2010). Research on fatherhood in indigenous cultures, including Australian Indigenous communities, is underexplored when compared with research conducted with men from White, married, well-educated, and middle-to-high socioeconomic backgrounds (Astone, 2014; Garfield, Clark-Kauffman, & Davis, 2006). One important study among African American men identified the benefits of parenting for men. The study reported that fathers valued learning about child-rearing, child health, and development (Smith, Tandon, Bair-Merritt, & Hanson, 2015). Because of the general lack of research, the health benefits or risks of parenting for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander men are empirically unknown. Anecdotal evidence and local knowledge, however, strongly suggests that the parenting role is positively associated with men’s psychological well-being (Adams, 2006; Laliberté, Haswell, & Tsey, 2012; McCalman et al., 2006b; Tsey et al., 2002; Tsey et al., 2004). Previous research with non-indigenous men indicates the transition to fatherhood may have varied effects on men’s health, from negative, to positive, to neutral (Garfield, Isacco, & Bartlo, 2010). Emotional responses related to the prospect of parenting for the father-to-be can include feeling unprepared and anxious, and experiencing role strain (Bartlett, 2004). The significance of this major life change for a male first-time parent has been identified as a dominant stressor (Fägerskiöld, 2008). An Australian prospective study identified increased levels of stress during pregnancy and the first year of the child’s life for first-time fathers (Condon et al., 2004). A large longitudinal study in the United States of depressive symptoms among young men during the transition to fatherhood reported that fathers experienced a decrease in depressive symptoms in the period before fatherhood and then experienced a 68% increase in depressive symptoms throughout the child’s first 5 years of life (Garfield et al., 2014). A study examining physical health and parenting identified that the time spent with children, the degree of worry about children, and satisfaction with the parental role had no influence on men’s subsequent risk of death or diagnosis of heart disease, stroke, or cancer (Hibbard & Pope, 1993).

Anecdotal and qualitative studies in Australian Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities have reported that the role of men as parents is valued as important to men’s general well-being (Adams, 2006; Tsey et al., 2002). The positive health effect of parenting on men has also been documented in literature relating to African American men (Smith et al., 2015). The association between Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander men’s well-being and parenting may be explained by the intrinsic value of the male historical role and its relationship to child development, particularly in the initiation of older boys into traditional manhood (Walker, 1977). The importance placed on Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander men to be strong role models for their sons and other children may be associated with this specific proclivity to embrace the parenting role (Read, 2000). It appears likely that the influence of Western gender roles have altered the expectation of fathers and their partners regarding men as parents (Cabrera et al., 2000). Through exposure to Western models of maternal and child health care, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women may, for example, expect that their partners will now play a more significant role in assisting with the care of children, including babies and young infants. These assumptions currently have not been tested empirically in the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander context.

The objective of this study was to qualitatively analyze data gathered from stakeholders in communities where the SFSF program was being offered. The findings were intended to be used directly in the SFSF men’s group intervention to promote male parenting, as well as to inform community health and welfare services related to male parenting and the care of babies, infants, and children. Another aim is to enhance the limited literature on Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander men’s parenting. Participants in the study included the SFSF men’s group facilitators and health and welfare workers from local Indigenous communities. Participants examined the challenges faced by fathers and the factors that enable men to engage in parenting roles. An additional study is currently investigating the relationship between parenting and Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander men’s mental health and well-being.

Method

Sample

To examine the challenges and barriers to parenting for men, 31 key stakeholders from across three Lower Gulf of Carpentaria communities were interviewed by the first author, an Aboriginal male project officer (see communities in Figure 1). The study was conducted in 2011, and all sites at that time offered the SFSF program. A qualitative method was selected because this was a hitherto unexplored area of knowledge and there were not many participants with the specialized knowledge required available to inform the study. The qualitative study complied with the Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research (COREQ; Tong, Sainsbury, & Craig, 2007). Participants were from either men’s groups or community health and welfare agencies with an interest in supporting men’s parenting. They were recruited from a qualitative, non-probabilistic expert sampling approach, which included a snowballing recruitment process (Tashakkori & Teddle, 2003). Expert sampling enabled researchers to recruit experts with specific knowledge about men’s parenting as participants (Gentles et al., 2015). A male facilitator from each men’s group offering the SFSF program in the three participating communities was specifically recruited. In addition to the three men’s group participants, the authors prioritized the inclusion of expert knowledge and support for men as parents over the gender of selected participants. Participants were employed in Aboriginal health care and related programs servicing Indigenous families, such as maternal and child health, child safety, and social services. Participants with expert knowledge were located and invited using a snowballing method. This method valued the knowledge of each participant and his or her capacity to identify other suitably informed participants. For example, discussion about the project with one participant led to a discussion with another participant, who suggested the project officer speak with another participant, and so forth (Salganik & Heckathorn, 2004). Two program sites were identified as Aboriginal communities, and one community had a high proportion (almost half) of Aboriginal people. Participants in the study included 25 Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people, 16 males and 9 females with ages ranging from 25 to 75 years, as well as 6 non-Aboriginal and Torres Strait people, 2 males and 4 females with ages ranging from 40 to 60 years (Table 1). This article is a secondary analysis of the SFSF program data and the primary report document, which has been published online by the program funders, the RFDS.

Table 1.

Participant Profile.

| Communities | Participants | M/F | Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Non-Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander |

|---|---|---|---|

| Doomadgee | 8 | 4 = M 4 = F |

8 = Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders |

| Mornington Island | 11 | 9 = M | 9 = Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders |

| 2 = F | 2 = Non-Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders (Female: Child and Family Health Nurses) |

||

| Normanton | 12 | 5 = M | 8 = Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders (5 female, 3male) |

| 7 = F | 4 = Non-Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander (2 female, 2 male) |

Process

Yarning refers to an Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander way of verbally sharing knowledge (Geia, Hayes, & Usher, 2013). Yarning can include storytelling or discussions in groups and is an important cultural method for sharing values, expectations, mores, and beliefs with younger generations (Geia, Hayes, & Usher, 2013; Nagel et al., 2011). Yarning has also become a recognized method for Indigenous research (Bessarab & Ng’andu, 2010). In this study, yarning incorporated accepted principles of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander research practice, including respect for Aboriginal ways of knowledge sharing within the context of a standardized qualitative focus group approach (Gwynn et al., 2015; Wilson, 2003). The yarning session method enabled the application of rigorous qualitative research standards of a focus group, which involves a systematic approach to sharing ideas and knowledge concerning key areas of inquiry. Discussion was driven by a thematic focus on each of the research questions (Tong et al., 2007). This process accords with reciprocal knowledge building that is embodied in yarning (Bessarab & Ng’andu, 2010). The facilitator encouraged the exploration of ideas and questions relating to each theme. Emerging ideas and contributions could be refined or clarified, and new areas of inquiry could also be pursued within the group (Geia, Hayes, & Usher, 2013).

The key research questions applied in the yarning groups mirrored those applied in the SFSF program. Those areas of knowledge were originally derived from preliminary discussions with communities and a piloted study with men’s group participants. Research questions included the following: What are culturally appropriate family roles for men and women within their community? What are culturally appropriate processes to support men’s engagement in antenatal, early childhood, and family health-care services? What are the barriers for men participating in antenatal, early childhood, and family health care, and how can men overcome these barriers? How can men better access resources to allow them to increase their knowledge and understanding of participating in their children’s and families’ lives?

Ethics and Consent

Data applied in this paper were collected as part of a program evaluation of SFSF that was funded and implemented by RFDS. The primary data from the evaluation is available online at www.flyingdoctor.org.au/what-we-do/research/. The RFDS requires strict adherence to its organizational research policy and research procedures, which are available upon request at FederationOfficeEnquiries@rfds.org.au. All participants provided verbal agreement to participate after being fully informed about the reasons for their participation and the aims of the evaluation. The collection and secondary analysis of data from the RFDS described in this article was undertaken in adherence with its ethical procedures and standards. Ethical conduct during this study also adhered to the National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Research Council and National Health and Medical Council guidelines, which are available at https://www.nhmrc.gov.au/guidelines-publications/e52.

Data Collection and Analysis

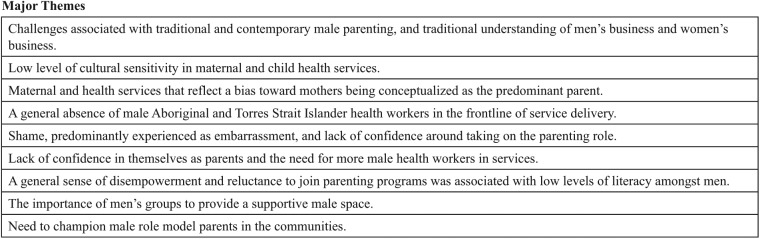

Data were recorded using an audio recorder with permission from participants. The groups were small and the researcher kept notes on who was contributing comments throughout the discussion. Data were de-identified, except for the participant’s role in the community. Data were transferred into text in preparation for analysis. De-identified data were kept in a locked computer in a locked office for the requisite time required by the Aboriginal Health & Medical Research Council of New South Wales (AH&MRC). A thematic analysis of the dataset was conducted and resulted in rich descriptions of the dominant themes (see themes in figure 2). Data was read line by line within the broad domains of the research questions as they were applied during the yarning groups. The dominant themes were identified according to the most common and the most strongly articulated issues. Views and perspectives relevant to themes were both contradictory and confirmatory. Data that were aligned with the themes were color coded, and further analysis of each comment was undertaken to fully understand and interrogate its meaning and relevance within the broader dataset. Two raters independently examined and coded the data, and minor differences were reconciled by consultation. With only one source of data from the SFSF project, triangulation was undertaken by separately examining data from each of the three communities to confirm or challenge trends and conclusions (Tong et al., 2007). Findings from the three communities was confirmatory. Using this method, knowledge was transferred from the 31 participants into thematic categories that could be applied to answer the primary research questions (Ward, House, & Hamer, 2009). A preliminary report on the data was crossed-checked with the participants before being revised and finalized (Lincoln & Guba, 1988; Tong et al., 2007).

Figure 2.

Table of thematic analysis.

Results

Men’s Business and Women’s Business

It was identified that in the past, family roles were determined strictly by lore, that is, men’s business and women’s business. This lore has now changed according to new ways of thinking and living after colonization. An Aboriginal female participant declared: “In the old days, child bearing . . . and the raising of the children was only women’s business” and “In the old days it was taboo for men to get involved in the upbringing of child—even child birth—that was women’s business.” An Aboriginal male went on to state, “This was the period when men participated in the upbringing of only the male child, and not until the boy turned a certain age did he become part of men’s business through initiation.” Here the male participant is referring to the initiation of male boys into men, known in this region as the Bora Ring ceremony. It was lamented that these traditional practices seem to be less commonly practiced within many contemporary Aboriginal communities and that new expectations to help with babies and young children were now placed on men, often by health authorities, which influence new mothers’ own expectations of men. In turn, men felt unprepared for these new expected roles and perceived a loss of their traditional role in passing on knowledge. One Aboriginal male participant stated: “The old ways for fathers was to pass their knowledge on . . . but that has stopped a long time ago.” Nonetheless, it was also stated by several other Aboriginal male participants that they still undertake cultural practices such as traditional hunting, and through these practices, men are still involved in sharing traditional knowledge and therefore the upbringing of the children. Another Aboriginal male participant explained that the process still involves “taking them (children) fishing and going on country (traditional land) to camp and go back to the old ways” (SFSF report, 2016, p 3). Participants explored how Western culture had changed the parenting roles of men and women. It was identified that only the men worked in the old days after colonization, and the women’s role was to stay at home and look after and raise the children. The men would only get involved if it had to do with disciplining the children (SFSF report, 2016, p. 3).

An Aboriginal female participant’s view was “Once upon a time men were the breadwinners and women stayed at home [to] look after the kids.” In contemporary society, this way of thinking is shifting, with more women being employed, creating an expectation of equal shared parental responsibility. In the modern context, it was viewed that the changed times had to be acknowledged and that young men now require support to take on the important role of parenting their young children and helping their partners more equally in the shared parental role. A non-Aboriginal female participant (child and family health nurse) explained that from her vantage point, there are already many examples of young men successfully taking on this challenge: “Young fathers do stand out as playing a fatherly role towards their children.” It was agreed that these young men should be promoted as role models and that these new approaches to parenting should be better understood and valued by all young indigenous parents.

Shame

The SFSF yarning sessions identified the importance of working in this way to shift the mindset of certain people in the community about the traditional parenting roles expected of men and women. This is a challenge because the value of men’s business and women’s business is seen to be needed to be upheld for traditional and cultural reasons. It was however stated that many men are merely acting on what they saw when they were growing up. Therefore, a newer approach to parenting may be better understood as a matter of transgenerational change, rather than as being in opposition to tradition. It was suggested by several Aboriginal female participants that one of the reasons that prevent men from taking on the role of parents is that they do not see enough role models or “good male leaders” as parents. Several male participants said that men feel “shame” about their role as parents, an Indigenous term used to describe an individual being embarrassed, and that through peer pressure to be “a real man,” men feel reluctant to engage in parenting. Contextual factors related to colonization, such as transgenerational trauma, gambling, and alcohol, drug and substance abuse were identified as factors that created stigma about the responsibility and capacity of male carers. These barriers to men engaging with their children and partners need to be acknowledged, and this stigma challenged in order to empower men to be confident fathers.

Overcoming Shame

It was identified through yarns that men prefer culturally appropriate services that are run by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander men. An example included the Mornington Island Men’s Group program, which provides health information sessions related to spiritual, emotional, and social well-being. These sessions allow health educators to talk to men about their health and well-being in a culturally sensitive way to ensure that men do not feel shame. The spiritual, emotional, and social well-being component of the program encourages men to attend community centers that provide appropriate services for men, such as individual, family, and community health programs. A non-Aboriginal female participant noted that participating men were either more confident to engage with a group or they became more empowered since their involvement in the group: “It looks like that men who attend the men’s group are more engaged in the community than the other men who don’t attend men’s groups.” It was also recognized that a culturally appropriate solution was to have service providers and community organizations employ local male leaders. These men act as role models within the community and provide culturally appropriate and informed advice for men who attend those services. An Aboriginal male participant said:

You know why men don’t go along to community health. . . because they’re all women. If we are going to be serious about getting men along to these services they need to start employing local fellas; fellas who are seen as leaders within this community.

Leaders such as Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander male health workers were seen to be the key to providing a culturally appropriate way for men to attend health services. One Aboriginal male participant stated: “We need to see more male black faces at the frontline of our Community Health Service here in Mornington Island.” Furthermore, it was considered important for service providers to engage with and support male health workers to encourage and promote men’s roles as fathers, grandfathers, and uncles. As suggested by one Aboriginal male participant: “The male health workers there at Community Health should be supported by their boss to come along to men’s groups and let the men know what services are being delivered up there” (SFSF report, 2016, pp. 4, 5).

Using Men’s Groups to Promote Male Role Models

Participants said that the overall responsibility for men to be active in their children’s lives should be determined by men themselves. For this reason, using a men’s group as a place that promotes and respects male autonomy is a good mechanism for men to learn more about antenatal and early childhood practices and programs, and men’s possible role in parenting. Men’s groups were commonly suggested by participants as a way of harnessing men’s self-sufficiency in a familiar setting to learn more about parenting. One Aboriginal male participant said: “Men groups are an ideal place for men to get some knowledge about parenting. . . . Having [a] men’s shed (gathering place) [that is] coordinated by someone who lives in the community. . . to advocate the roles of father involvement in their children’s life.” Another participant explained: “Men’s groups are places where men [through support and education] can be confident when they may need to attend or actively participate in health services.”

Men’s group meetings were also considered to be possible safe places for fathers to take their children, where they could parent without any concern related to shame or judgement by others. It was further articulated that men’s groups have emerged in a diversity of ways, including men’s gathering groups related to rugby league football. It was suggested by several participants that the ruby league players could be role models with regard to health screening, including for issues related to sexual health and the role of men in caring for children during early childhood. One Aboriginal female participant stated: “It’s not only about playing footy, the players on sign up day also sign to agree to get regular health checks” (SFSF report, 2016, pp. 5, 6).

Improving Men’s Educational Status

An overwhelming response by Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal participants about the challenges for men participating in their children’s upbringing was the lack of local and accessible information-sharing processes related to men’s roles as fathers, uncles, and grandfathers within their own communities. The lack of accessible information resulted in men distancing themselves from attending community-run parenting programs, including antenatal and early childhood development programs. It was also identified that the low numeracy and literacy levels of many men within communities creates low self-esteem, and that this contributes to their alienation from health services that attempt to provide parenting knowledge. These issues are associated with the aforementioned feelings of “shame” experienced by Aboriginal men. One non-Aboriginal female participant said: “More than likely, some men in this community don’t attend training workshops because they can hardly read” (SFSF report, 2016, pp. 6, 7). While improving educational status generally at a community level may take time, one non-Aboriginal female participant (Child and Family Health Nurse) suggested that at least “education” could just focus on the service that is being offered: “Through education and shifting the mindset of men [they can] understand that it is OK to attend health service[s] and participate in antenatal and early child development programs” (SFSF report, 2016, p 9).

Improving Service Delivery

Programs that focus on caring for babies and children should target both men and women. It was suggested that some government and nongovernment service providers lacked community engagement skills. There was a need to “get out and talk to community people.” Participants also expressed the need for service providers to improve delivery by providing a culturally appropriate service for men. This reflects the need for more Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander men to be trained and employed in these roles. One Aboriginal male participant stated that the services did not offer a “father-friendly environment” and that “there should also be men working in that field . . . in parental programs.”

The group, particularly the male participants, identified that programs such as antenatal care were too female-focused and in this way, they excluded men from participating. The yarning sessions identified that men felt particularly isolated from parenting programs when the gendered name of a program automatically excluded men from having an active parenting role. For example, one of the dominant community programs is called “Mums and Bubs.” The group noted that the lack of funding generally meant that men may be resented for trying to get involved in programs that have been established for women.

Sharing Knowledge Through Men’s Groups

Culturally appropriate avenues for knowledge sharing such as men’s groups and men’s gathering places are important sites to share educational resources about antenatal and early childhood issues. It was noted that there is a need to provide men with good opportunities to make informed decisions with regard to understanding and attending these programs. An Aboriginal male participant (men’s group coordinator) suggested that parenting can be incorporated into health-sharing nights in the men’s group: “We do leather work Tuesday nights, on Wednesday nights we have health talk where we invite health workers up to have a yarn about certain health issues.” It was also suggested that local media such as radio, the local paper, and newsletters may be useful in promoting the parenting role and responsibilities of fathers, uncles, and grandfathers. An Aboriginal female participant said: “We have a radio station here, [the] men’s group should go there and talk about men’s [responsibility to be] good dads.” The group called on the support of local government and interagency collaboration to engage in a strategy to invite health service providers to attend men’s meetings and provide educational workshops and support related to men’s parenting (SFSF report, 2016, pp. 10, 11).

Discussion

This study has, for the first time, systematically identified barriers and opportunities to support Australian Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander men’s role as parents (Table 1). The study was undertaken by stakeholders working with parents and men in remote Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities. The study has highlighted the need for an awareness in services for men’s parenting role, which may be impacted by traditional understanding of men’s business and women’s business, and additional difficulties in undertaking contemporary parenting practices. Challenges for male parents included a low level of cultural sensitivity in maternal and child health services, which reflect a bias toward mothers being conceptualized as the primary parent, and a general absence of male Aboriginal health workers in the front line of service delivery. Shame, predominantly experienced as embarrassment, and a lack of confidence around parenting were additional challenges. The lack of confidence in men as parents was associated with the absence of support and encouragement for male parents in health and community services. A general sense of disempowerment was associated with low levels of literacy amongst men. These findings highlight the importance of men’s groups in providing a supportive male space and championing male parental role models in Indigenous communities.

The strengths and limitations of the study need to be considered. The inclusion of 25 Australian Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander and 6 non-Indigenous community stakeholders from three remote communities is rare in a systematic study of this hitherto unexplored field. The qualitative method proved to be invaluable in providing a detailed and rich account of this area of inquiry. The study findings were however exploratory, and they cannot be generalized to other communities. The findings were nevertheless instructive, and, clearly, replication with representative populations of stakeholders is necessary. While female participants were included because of their expertise and knowledge as community stakeholders, the male voice and perspective in relation to this topic could have been attenuated or influenced by their inclusion. Although 6 non-Indigenous Aboriginal community participants were included, the authors separately examined their data and intentionally prioritized the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander voice. The results offer guidance in developing policy and practice in the men’s parenting and maternal health field, especially because there is a dearth of research focusing specifically on men in these contexts. The current findings of male feelings of shame and disempowerment related to parenting, and the compelling non-Indigenous literature on male parenting and depressive symptoms, support the need for research into Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander men’s mental health in the context of male parenting (Garfield et al., 2014).

The yarning data is able to be categorized according to biases identified in a global study that examined the relative exclusion of men from parenting interventions (Panter-Brick et al., 2014). Four categories of bias warrant consideration as a method for informing future policy and practice.

Cultural Biases

Conflicting expectations of traditional and contemporary ways of parenting are not adequately understood or incorporated into current policy and practice. This study identifies that cultural parenting practices such as fishing and hunting with older boys, as well as contemporary male parenting behaviors such as changing diapers and caring for infants, are both being practiced. While cultural parenting practices are considered at risk of being undermined by modern life and its expectations, contemporary parenting of babies and young children is culturally unfamiliar for many men. The cultural complexity of male parenting roles need to be understood and valued. The styles and practices of male parents should be documented, and staff working in communities should be formally acquainted with this knowledge. Staff also need to be aware that Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander men may not have sufficient confidence or knowledge to engage fully in the contemporary parenting role and that support and encouragement is required.

Institutional Biases and Professional Biases

Parenting and child-related services should explicitly reflect and promote the importance of male parenting, including having Aboriginal men at the forefront of service delivery. Services should not have gendered names such as “maternal and child health” and “Mums and Bubs.” These gendered terms alienate men and exclude them from participating in parenting programs. Services should generally be strategically informed and culturally sensitive to the factors that may prevent men from engaging with them, and should instead be encouraging.

Content and Resources Biases

Many of the resources available to men were not culturally sensitive, and they were often not designed or delivered by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander men themselves. Low literacy is associated with low self-esteem and “shame,” and together, these factors prevent men from attending programs that offer parenting education. It is vital for parenting services to offer programs designed for men with very low literacy. From a broader policy perspective, governments need to prioritize improving Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander men’s literacy and numeracy, as this can have profound impacts on their psychological well-being and capacity to engage in health programs.

Policy Bias

Policy is biased in favor of those motivated to engage with services. The level of disempowerment amongst marginalized groups, including Indigenous men, needs to be incorporated into policy. Empowerment theory would better inform the development of programs to include male parents (Wallerstein & Bernstein, 1994). Empowerment approaches focus on facilitating a structural analysis of the factors that work to undermine men’s confidence in parenting, such as colonization and its effects on men, racial disadvantage and marginalization, and negative stereotypes about men and their use of alcohol and drugs. Empowerment approaches have been reported to support men to establish positive thoughts, behavior, and emotions, to sustain positive change, and to develop the capacity to help others (Laliberté et al., 2012; Rees et al., 2004). Ultimately, empowerment approaches need to foster community action to promote men’s roles and family and community inclusion.

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander men’s groups, as well as other male support groups interested in strengthening the parenting role for men, should consider the issues that were identified in the yarns. It was aptly said that the parenting role strengthens the father’s identity; if you have strong fathers, you will have strong families, and if you have strong families, you will have strong communities.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- Adams M. (2006). Raising the profile of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander men’s health: An indigenous man’s perspective. [Google Scholar]

- Adams M., Danks B. (2007). A positive approach to addressing indigenous male suicide in Australia. Aboriginal and Islander Health Worker Journal, 31, 28. [Google Scholar]

- Astone N. M. (2014). Longitudinal influences on men’s lives: Research from the Transition to Fatherhood Project and beyond. Fathering, 12, 161. [Google Scholar]

- Bartlett E. E. (2004). The effects of fatherhood on the health of men: A review of the literature. The Journal of Men’s Health & Gender, 1, 159–169. [Google Scholar]

- Bessarab D., Ng’andu B. (2010). Yarning about yarning as a legitimate method in indigenous research. International Journal of Critical Indigenous Studies, 3, 37–50. [Google Scholar]

- Bond M. J. (2010). The missing link in MCH: Paternal involvement in pregnancy outcomes. American Journal of Men’s Health, 4, 285–286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bornstein M. H. (2012). Cultural approaches to parenting. Parenting, 12, 212–221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bulman J. (2009). ‘Mibbinbah’ - an initiative for indigenous men. Health Voices, 5, 16–17. [Google Scholar]

- Cabrera N. J., Tamis-LeMonda C. S., Bradley R. H., Hofferth S., Lamb M. E. (2000). Fatherhood in the twenty-first century. Child Development, 71, 127–136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Condon J. T., Boyce P., Corkindale C. J. (2004). The first-time fathers study: A prospective study of the mental health and wellbeing of men during the transition to parenthood. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, 38, 56–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dudgeon P., Wright M., Paradies Y., Garvey D., Walker I. (2010). The social, cultural and historical context of aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians. In Purdie N., Dudgeon P., Walker R. (Eds.), Working together: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander mental health and wellbeing principles and practice (pp. 25–42). Canberra: Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, Canberra. [Google Scholar]

- Fägerskiöld A. (2008). A change in life as experienced by first-time fathers. Scandinavian Journal of Caring Sciences, 22, 64–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furber-Gillick D. (2011). What role does kinship play in indigenous practices of sharing? Southerly, 71(2). [Google Scholar]

- Garfield C., Isacco A., Bartlo W. D. (2010). Men’s health and fatherhood in the urban Midwestern United States. International Journal of Men’s Health, 9, 161. [Google Scholar]

- Garfield C. F., Clark-Kauffman E., Davis M. M. (2006). Fatherhood as a component of men’s health. JAMA, 296, 2365–2368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garfield C. F., Duncan G., Rutsohn J., McDade T. W., Adam E. K., Coley R. L., Chase-Lansdale P. L. (2014). A longitudinal study of paternal mental health during transition to fatherhood as young adults. Pediatrics, 133, 836–843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geia L. K., Hayes B., Usher K. (2013). Yarning/Aboriginal storytelling: Towards an understanding of an Indigenous perspective and its implications for research practice. Contemporary Nurse, 46, 13–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gentles S. J., Charles C., Ploeg J., McKibbon K. A. (2015). Sampling in qualitative research: Insights from an overview of the methods literature. The Qualitative Report, 20, 1772. [Google Scholar]

- Gwynn J., Lock M., Turner N., Dennison R., Coleman C., Kelly B., Wiggers J. (2015). Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander community governance of health research: Turning principles into practice. Australian Journal of Rural Health, 23, 235–242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton A. (1980). Dual social systems: Technology, labour and women’s secret rites in the eastern Western Desert of Australia. Oceania, 51, 4–19. [Google Scholar]

- Hayman N. (2010). Strategies to improve indigenous access for urban and regional populations to health services. Heart, Lung and Circulation, 19, 367–371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hibbard J. H., Pope C. R. (1993). The quality of social roles as predictors of morbidity and mortality. Social Science & Medicine, 36, 217–225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laliberté A., Haswell M., Tsey K. (2012). Promoting the health of Aboriginal Australians through empowerment: Eliciting the components of the Family Well-being Empowerment and Leadership Programme. Global Health Promotion, 19, 29–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lincoln Y. S., Guba E. G. (1988). Criteria for assessing naturalistic inquiries as reports. [Google Scholar]

- Lowe H., Spry F. (2002). Living male: Journeys of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander males towards better health and well-being. Retrieved from http://hdl.handle.net/10137/123

- Marmot M. (2011). Social determinants and the health of Indigenous Australians. The Medical Journal of Australia, 194, 512–513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCalman J., Tsey K., Wenitong M., Ahkee D., Jia A., Ambrum D., Wilson A. (2006. a). “Doing good things for men”: Ma’Ddaimba-Balas Indigenous Men’s Group Evaluation Report: 2004–2005. Cairns: James Cook University. [Google Scholar]

- McCalman J., Tsey K., Wenitong M., Whiteside M., Haswell M., James Y. C., Wilson A. (2006. b). Indigenous men’s groups - what the literature says. Cairns: James Cook University. [Google Scholar]

- McIntyre-Tamwoy S. (2008). Archaeological sites & Indigenous values: The Gondwana Rainforests of Australia World Heritage Area. Archaeological Heritage, 1, 42–49. [Google Scholar]

- Nagel T., Hinton R., Thompson V., Spencer N. (2011). Yarning about gambling in indigenous communities: An Aboriginal and Islander mental health initiative. Australian Journal of Social Issues, 46, 371–389. [Google Scholar]

- Opondo C., Redshaw M., Savage-McGlynn E., Quigley M. A. (2016). Father involvement in early child-rearing and behavioural outcomes in their pre-adolescent children: Evidence from the ALSPAC UK birth cohort. BMJ Open, 6, e012034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panter-Brick C., Burgess A., Eggerman M., McAllister F., Pruett K., Leckman J. F. (2014). Practitioner review: Engaging fathers–recommendations for a game change in parenting interventions based on a systematic review of the global evidence. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 55, 1187–1212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Purdie N., Dudgeon P., Walker R. (2010). Working together: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander mental health and wellbeing principles and practice. Canberra, ACT: Australian Government Department of Health and Ageing. [Google Scholar]

- Read P. (2000). Belonging: Australians, place and Aboriginal ownership. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Rees S., Tsey K., Every A., Williams E., Cadet-James Y., Whiteside M. (2004). Empowerment and human rights as factors in addressing violence and improving health in Australian Indigenous Communities. Health and Human Rights, 8(1), 94–113. [Google Scholar]

- Reilly L. (2008). Through the eyes of Blackfella’s. Centre for Domestic and Family Violence. Rockhampton: Central Queensland Universtity Thesis. [Google Scholar]

- Rowe A. C., Tuck E. (2017). Settler colonialism and cultural studies: Ongoing settlement, cultural production, and resistance. Cultural Studies ↔ Critical Methodologies, 17, 3–13. [Google Scholar]

- Salganik M. J., Heckathorn D. D. (2004). Sampling and estimation in hidden populations using respondent-driven sampling. Sociological Methodology, 34, 193–240. [Google Scholar]

- Smith T. K., Tandon S. D., Bair-Merritt M. H., Hanson J. L. (2015). Parenting needs of urban, African American fathers. American Journal of Men’s Health, 9, 317–331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tashakkori A., Teddle C. (2003). Handbook of mixed methods in social & behavioral research. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 759. [Google Scholar]

- Tong A., Sainsbury P., Craig J. (2007). Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): A 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. International Journal for Quality in Health Care, 19, 349–357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsey K., Patterson D., Whiteside M., Baird L., Baird B. (2002). Indigenous men taking their rightful place in society? A preliminary analysis of a participatory action research process with Yarrabah Men’s Health Group. Australian Journal of Rural Health, 10, 278–284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsey K., Patterson D., Whiteside M., Baird L., Baird B., Tsey K. (2004). A microanalysis of a participatory action research process with a rural Aboriginal men’s health group. Australian Journal of Primary Health, 10, 64–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker K. (1977). An Aboriginal view of Australian history. The Aboriginal Child at School, 5, 14–16. [Google Scholar]

- Wallerstein N., Bernstein E. (1994). Introduction to community empowerment, participatory education, and health. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ward V., House A., Hamer S. (2009). Developing a framework for transferring knowledge into action: A thematic analysis of the literature. Journal of Health Services Research & Policy, 14, 156–164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson S. (2003). Progressing toward an Indigenous research paradigm in Canada and Australia. Canadian Journal of Native Education, 27, 161–178. [Google Scholar]