Abstract

Retinoic acid (RA) is a vital morphogen for early patterning and organogenesis in the developing embryo. RA is a diffusible, lipophilic molecule that signals via nuclear RA receptor heterodimeric units that regulate gene expression by interacting with RA response elements in promoters of a significant number of genes. For precise RA signaling, a robust gradient of the morphogen is required. The developing embryo contains regions that produce RA, and specific intracellular concentrations of RA are created through local degradation mediated by Cyp26 enzymes. In order to elucidate the mechanisms by which RA executes precise developmental programs, the kinetics of RA metabolism must be clearly understood. Recent advances in techniques for endogenous RA detection and quantification have paved the way for mechanistic studies to shed light on downstream gene expression regulation coordinated by RA. It is increasingly coming to light that RA signaling operates not only as precise concentrations but also employs mechanisms of degradation and feedback inhibition to self-regulate its levels. A global gradient of RA throughout the embryo is often found concurrently with several local gradients, created by juxtaposed domains of RA synthesis and degradation. The existence of such local gradients has been found especially critical for the proper development of craniofacial structures that arise from the neural crest and the cranial placode populations. In this review we summarize the current understanding of how local gradients of RA are established in the embryo and their impact on craniofacial development.

Keywords: Cyp26, craniofacial, degradation, gradient, neural crest, placode, Raldh, retinoic acid

1- General Introduction

Development is a highly ordered and complex process, during which cells must undergo autonomous changes, as well as respond to local and distant morphogen gradients in a timely fashion. Therefore these gradients must be stable, precise in concentration, temporally and spatially accurate, and most importantly, specific in the responses they evoke. In addition, gradients must be able to interact with one another in a coordinated fashion. Retinoic Acid (RA) is a key morphogen during vertebrate embryogenesis and organogenesis, and RA gradients fulfill these parameters through auto-regulation, dose-dependence and by mechanisms that create “RA-free” zones adjacent to RA producing zones. This gradient is then efficiently interpreted by cells to yield complex patterns of gene expression, in both vertebrates and invertebrates. Regulation of gene expression by RA is achieved through receptor-mediated transcriptional modulation, involving several families of nuclear receptors. The pathway from RA synthesis to gene regulation is orchestrated by the action of an ensemble of factors, and is executed with multiple layers of regulation.

RA has well-documented roles in cell growth, patterning, fate specification, and differentiation, apoptosis, immune response and maintaining circadian rhythms (Gudas and Wagner 2011) (Mora, Iwata et al. 2008) (Teletin, Vernet et al. 2017) (Ransom, Morgan et al. 2014). During development it is considered especially critical for the formation of the vertebrate head. Given the plethora of functions regulated by RA, it is unsurprising that it has been extensively studied for decades and its importance in normal development and physiological function is well established. This review focuses on the role of RA signaling in the regulation of anterior structures in the developing embryo, and how the balance between regulation of RA production and degradation domains is essential to establish specific pattern of gene expression. We also discuss methods for the detection and quantification of RA levels from biological samples that are likely to advance our understanding of RA signaling in development.

2- RA biogenesis and signaling pathway

RA is derived from Vitamin A (retinol), and biomolecules that resemble retinol in chemical structure or function are known as retinoids. Early sources of Vitamin A include maternal diet, or yolk in non-mammal vertebrates. Retinoids are light-sensitive molecules that are hydrophobic and lipophilic, with low molecular weight (up to 300 Daltons), and are capable of diffusing across cell membranes (Kam, Deng et al. 2012). Intracellulary, retinol is modified through a series of oxidation steps, culminating in the production of RA. Endogenous RA exists as three stereoisomers: all trans RA (atRA), 9-cis RA and 13-cis RA, of which atRA and 9-cis RA are the biologically active forms (Kojima, Fujimori et al. 1994).

There are multiple sources of RA in a developing embryo. These regions are enriched in RA synthesizing enzymes grouped under aldehyde dehydrogenases (ALDHs) and retinaldehyde dehydrogenases (RALDHs), which oxidize retinaldehyde to RA (Figure. 1). In order to regulate gene expression, RA is transported from the cytosol to the nucleus with the aid of cytoplasmic retinoid binding proteins (CRBPs) cellular retinoic acid-binding protein 1 and 2 (CRABP1 and CRABP2). CRBPs participate in setting the endogenous cellular concentration of RA by binding and sometimes sequestering the ligand to prevent its degradation. This interaction is used to actively channel RA to RA-receptors (RARs) in the nucleus (Dolle, Ruberte et al. 1990, Noy 2000). Unbound RA is typically degraded in the cytoplasm and therefore does not have any signaling function.

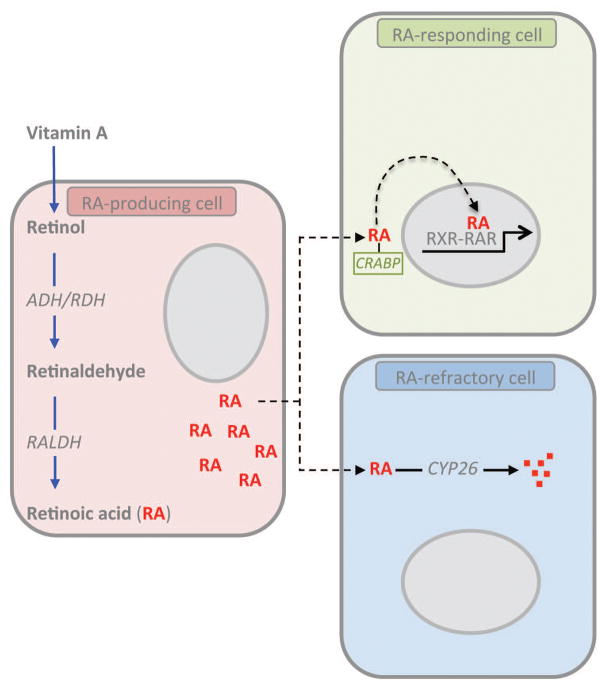

Figure 1. Retinoic acid production and signaling.

A schematic diagram of the three-types of cells involved in RA signaling. RA-producing cells (pink) uptake retinol synthesized from Vitamin A and undergo a series of enzymatic steps culminating in the synthesis of RA by RALDH. This RA can alter gene expression in the RA-producing cell (autocrine signaling) or diffuse to neighboring cells (paracrine signaling). Neighboring cells may be RA-responsive (green) or RA-refractory (blue). RA responsive cells uptake RA through cellular retinoid binding proteins such as CRABP and allow signaling through RAR/RXR heterodimers in the nucleus. These heterodimers interact with RA-responsive elements (RAREs) in the promoters of genes and result in gene activation or repression. RA-refractory cells express RA catabolizing Cyp26 enzymes that convert RA into polar metabolites that are cleared by the cell. Typically, RA-producing and RA-refractory cells are mutually exclusive.

RA can bind a variety of nuclear receptor families, including RA receptors (RARs) and retinoid-X receptors (RXRs) that facilitate canonical RA signaling (Wei 2003). RARs form heterodimers with RXRs, with each heterodimer acting as a transcription factor and binding to RA response elements (RAREs) in the promoter elements of target genes. RAR-related orphan receptors (RORs) also transduce RA, though their mechanism of action is poorly understood. RAR/RXR heterodimers bind RAREs with high affinity and utilize a diverse array of co-activators and repressors for rapid, and precise context-specific signaling. Unbound RA is degraded in the cytosol by a set of cytochrome P450 family of enzymes called the Cyp26 enzymes. Cyp26 enzymes rapidly catabolize RA into inactive polar metabolites that can be cleared by the cell. While cells that produce RA typically do not express Cyp26 enzymes, their expression can be induced by teratogenic RA levels in order to help maintain physiological RA concentrations. This mode of regulation is unique to RA, as other morphogens utilize antagonistic factors rather than ligand degradation to suppress signaling, and is further discussed in detail in subsequent sections. Finally, RA synthesis is also subject to negative feedback regulation by endogenous RA (Strate, Min et al. 2009), adding another means to the meticulous regulation of cellular RA levels.

3- RA signaling in development: an overview

Until recently, RA signaling was considered a unique feature of vertebrates, although components of RA signaling machinery have been documented in cephalochordates such as amphioxus (Koop, Holland et al. 2010) and even certain protostomes (Albalat and Cañestro 2009) (Albalat 2009). However, the role of RA in development is most clearly understood in vertebrates. RA signaling is required in a developing embryo from the very early stages and must persist into adulthood to maintain homeostasis, stem cell populations and nerve regeneration, to name a few (Maden 2007). However, it is especially critical during embryogenesis for the correct establishment of the vertebrate body plan. The first evidence that RA was acting as a morphogen came from studies showing an essential role for Vitamin A during development (Moore 1957, Hassell, Greenberg et al. 1977). This was followed by the identification of RA as the most biologically active form synthesized from Vitamin A, and to which the essential functions of Vitamin A are attributed (Zile 1998). Our understanding of RA signaling and metabolism in embryonic development has come a long way since then.

RA signaling in developing vertebrates begins in domains populated by cells that are capable of synthesizing RA and thus serving as “source”. Vertebrate embryos begin to express RALDHs shortly after gastrulation in the newly formed mesoderm (Swindell, Thaller et al. 1999, Reijntjes, Blentic et al. 2005). Genetic ablation of RA synthesizing enzymes in mice has shown that RA is required soon after implantation of the embryo for its survival (Niederreither, Subbarayan et al. 1999). In addition, perturbations in RA levels as early as gastrulation were shown to disrupt body axis formation via changes in expression of HOX family of genes (Durston, Timmermans et al. 1989) (Grandel, Lun et al. 2002), now known to be direct targets of RA signaling. Treatment of neurula stage Xenopus embryos with RA resulted in the formation of posterior structures at the expense of anterior regions (Ruiz i Altaba and Jessell 1991). Similarly, short treatments or low doses RA caused truncation of anterior and axial structures, while posterior structures remained unaffected (Durston, Timmermans et al. 1989, Cunningham, Mac Auley et al. 1994). Developing embryos are highly sensitive to RA levels prior to gastrulation, especially in the context of central nervous system (CNS) development, but become resistant to excess RA as the embryo proceeds from gastrulation to neurulation (Sive, Draper et al. 1990). Altogether, these observations have led to the notion that RA is a “posteriorizing factor” during embryonic development.

Of RA’s many functions, its roles in hindbrain patterning, neurogenesis, body axis elongation, somitogenesis, limb bud and digit formation, and eye, liver, heart and skeletal morphogenesis are especially well documented (for a comprehensive compilation, see (Dollé and Niederreither 2015)). In each instance, a specific set of RARE-containing target genes is activated or repressed to execute a specific developmental program. Altogether, RA is estimated to be involved in the transcriptional regulation of about 500 genes, including direct and indirect targets (Balmer and Blomhoff 2002). A significant body of research has now firmly established that RA act during early embryonic development in a dose-specific fashion. These roles of RA in development of the body are highly conserved across vertebrates, and these findings are summarized in several excellent publications (Weston, Hoffman et al. 2003, Luo, Sakai et al. 2006, Lewandoski and Mackem 2009, Zaffran and Niederreither 2015)((Cunningham and Duester 2015) (Maden 2007) (Glover, Renaud et al. 2006, Duester 2008, Rhinn and Dollé 2012).

Due to this widespread regulation of gene expression, RA is likely to operate at tightly defined intracellular concentrations that are specific for each cell-type. When this specific dosage is perturbed during development either from excess or lack of RA, a broad range of malformations is observed, which intriguingly often manifest as similar deformities in organs. Several developmental programs were disrupted in rat offspring from mothers raised on a Vitamin A deficient diet, resulting in fetal Vitamin A deficiency syndrome (VAD), a spectrum of developmental malformations affecting the hindbrain, eye, ear, heart, lung, limb and several other organs (Wilson, Roth et al. 1953). Conversely, exposure to excess RA during pregnancy resulted in defects in craniofacial, cardiac, and central nervous systems that were collectively termed RA embryopathy (RAE) (Lammer, Chen et al. 1985). Too much RA signaling is detrimental to embryonic development, and the malformations resulting in these cases depend upon the dose of RA administered and the stage of embryonic development during exposure (Soprano and Soprano 1995). In severe cases, lethality was noted. These findings are consistent with knockout studies in animal models that create conditions of teratogenic RA during development (Ross, McCaffery et al. 2000). The most recent model of RA teratogenicity shows that while RA has a short half-life, even an acute exposure to excess RA can induce a prolonged local RA deficiency by upregulation of the Cyp26 enzymes, sometimes even ectopically (Bonnard, Strobl et al. 2012). Similarly in zebrafish embryos, teratogenic doses of RA led to rapid and prolonged upregulation of Cyp26a1, as well as a slow and temporary repression of RA synthesis enzymes (Rydeen, Voisin et al. 2015). It is postulated that the deleterious effects of low and high RA are due to a severe impact on cell lineages that comprise the anterior neural structures in the embryo, discussed in subsequent sections.

4- CYP26-mediated RA gradients formation and regulation

4.1- CYP26 expression

Cytochrome P450 family of enzymes are heme-containing proteins that oxidize a wide range of vitamins, steroids and fatty acids, and are classified into subfamilies based on their preferred substrates (Furge and Guengerich 2006). These membrane-bound enzymes are present in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) and mitochondria, and require nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NADPH) to facilitate catalysis (Pennimpede, Cameron et al. 2010). RA catabolism is specifically mediated by the Cyp26 family of enzymes, which regulate cellular access to RA by creating strictly defined zones of RA distribution. Embryonic domains that are particularly sensitive to RA levels express Cyp26 enzymes. Each of the three Cyp26 family members are expressed in a distinct pattern depending on species and developmental age, to create either RA-free or low RA regions as discussed above. The developmental and tissue-specific expression of Cyp26 enzymes in mouse and Xenopus embryos is summarized in Table 1. For Chick and zebrafish data see (Rhinn and Dollé 2012) and (Samarut, Fraher et al. 2015)

Table 1.

Expression pattern of RALDHs and Cyp26 enzymes encoding genes

| Xenopus | Mouse | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Expression Domain | Reference | Expression domain | Reference | |

| Cyp26a1 | [St 10 onwards] Prospective anterior neuroectoderm, involuting mesoderm. [St 15] Presumptive midbrain and hindrain, and prechordal plate [St 48–50] Outer and basal layer of corneal epithelium and fibrillar layer of basal corneal epithelium. |

(Hollemann, Chen et al. 1998, Chen, Pollet et al. 2001, Thomas and Henry 2014) | [E12] Developing retina (equatorial region), retinal pigment epithelium. [E7.5] Head mesenchyme, neuroectoderm. [E9.5–10] Posterior neural tube and cranial neural crest cells, cranial ganglia, prospective hindbrain (transient), rhombomere 2. |

(Abu-Abed, MacLean et al. 2002, Sakai, Luo et al. 2004) (Fujii, Sato et al. 1997, Uehara, Yashiro et al. 2007) |

| Cyp26b1 | [St 48–50] Outer and basal layer of corneal epithelium. | (Thomas and Henry 2014) | [E12] Developing hindbrain (pons, cerebellum) and forebrain (striatum, hippocampus), retinal pigment epithelium [E8] Presumptive hindbrain [Later stages] Rhombomere 3, somites, limb bud. |

(MacLean, Abu-Abed et al. 2001, Abu-Abed, MacLean et al. 2002, Yashiro, Zhao et al. 2004, Uehara, Yashiro et al. 2007) |

| Cyp26c1 | [St 15] Prospective hindbrain, neural crest, placode area and cement gland primordium. [St 48–50] Lens. |

(Tanibe, Michiue et al., Thomas and Henry 2014) | [E12] Retina [E7.5] Head mesenchyme [E8–8.5] Hindbrain prospective (rhombomeres 2 and 4), first branchial arch [Late gestation] Inner ear and inner dental epithelium. |

(Sakai, Luo et al. 2004) (Tahayato, Dollé et al. 2003, Uehara, Yashiro et al. 2007) |

| Raldh1 | [St 28] Olfactory placode. [St 48–50] Outer and basal layer of corneal epithelium, lens. |

(Ang and Duester 1999, Thomas and Henry 2014) | [E9.5–10] Dorsal retina, otic vesicle, ventral mesencephalon, thymic primordia | (Haselbeck, Hoffmann et al. 1999) |

| Raldh2 | [St 10 onwards] Involuting mesoderm. [St 15] Anterior neural plate, and the paraxial trunk mesoderm. [St 25] Retina. [St 48–50] Lens, otic vesicle. |

(Chen, Pollet et al. 2001, Thomas and Henry 2014, Jaurena, Juraver-Geslin et al. 2015) | [E7.5 onwards] Paraxial and lateral plate mesoderm. [E8.5–9.5; transient] Ventral optic vesicle. [E14] Periocular mesenchyme. |

(Haselbeck, Hoffmann et al. 1999, Niederreither, Subbarayan et al. 1999) |

| Raldh3 | [St 48–50] Corneal tissue. | (Thomas and Henry 2014) | [E9 onwards] Ventral retina, otic vesicle, olfactory pit. | (Mic, Molotkov et al. 2000) |

Of the three Cyp26s, Cyp26a1 was the first to be discovered in a zebrafish screen for RA responsive genes (White, Guo et al. 1996). Cyp26b1 and c1 were discovered later through in silico analyses, and subsequently cloned and characterized (Nelson 1999, White, Ramshaw et al. 2000, Taimi, Helvig et al. 2004). Human Cyp26 enzymes share less than 55% amino acid similarity, but each of these genes shows greater conservation across species, with Cyp26b1 being most conserved and Cyp26c1 the least (Lee, Perera et al. 2007, Ross and Zolfaghari 2011). In other species, the conservation between the three Cyp26 enzymes is also between 40–50% (Lutz, Dixit et al. 2009). While Cyp26 enzymes have overlapping functions and similar kinetics, the level of redundancy varies from species to species. In zebrafish to mice, all three members of Cyp26 family are present, and a variety of in vitro and in vivo studies have shown that the Cyp26 enzymes can be upregulated by atRA (Ray, Bain et al. 1997, Taimi, Helvig et al. 2004, Zolfaghari, Cifelli et al. 2007, Thatcher, Zelter et al. 2010). During early mouse development, Cyp26a1 and b1 are expressed in the anterior domains of the embryo including the head mesenchyme and neuroectoderm, and become progressively restricted to the neural plate and the presumptive hindbrain (Abu-Abed, MacLean et al. 2002). Cyp26a1 and b1 persist through adulthood in tissues such as the liver, where as Cyp26c1 appears to be expressed mainly during embryonic development (Ross and Zolfaghari 2011). Cyp26a1 is expressed in the posterior neural plate and the prospective hindbrain, extending into rhombomere 2 as development progresses (Fujii et al. 1997). In contrast, Cyp26b1 initiates expression later, in rhombomere 3 and late in development is robustly expressed in the hindbrain, the developing somites, the distal aspect of the limb bud and the caudal branchial arches (MacLean, Abu-Abed et al. 2001, Yashiro, Zhao et al. 2004). Cyp26c1 is expressed in the prospective hindbrain during early development, and expands to the first brachial arch, the inner ear and the inner tooth epithelium later in gestation (Tahayato, Dollé et al. 2003), Table 1.

Many studies have shown the importance of these enzymes in the appropriate development of anterior structures in mice by establishing an uneven RA gradient. Notably, there appears to be some redundancy in the function of Cyp26 a1 and c1 in mice, where Cyp26c1 null mice exhibit normal development of the CNS, and Cyp26a1 null mice show mild to severe defects in the size of the head and neural tube closure (Uehara, Yashiro et al. 2007). The double-knockout (KO) of Cyp26a1/c1, however, showed drastic CNS defects (an anteriorly open neural tube, severely truncated head with a posteriorly enlarged hindbrain, and anterio-posterior (A-P) patterning defects), which could all be rescued by a concomitant ablation of raldh2, indicating that these defects are likely due to excess RA accumulation. Genetic ablation of Cyp26b1 resulted in craniofacial abnormalities, such as a shortened mandible and calvaria ossification defects, but the hindbrain was patterned normally (Maclean, Dollé et al. 2009). These defects resulted from a failure of neural crest cells to migrate appropriately into the third and fourth branchial arches, while the first and second branchial arches developed normally. Additionally, Cyp26b1 mice also exhibit limb patterning defects, consistent with the expression pattern of the enzyme. Loss of Cyp26b1 led to excess RA in the distal limb bud, resulting in an expansion of proximal limb structures at the expense of the distal structures that manifested as a meromelia-like defect (absence or shortening of limb with normal hands and feet)(Yashiro, Zhao et al. 2004). This is consistent with the fact that individuals with homozygous point mutations in CYP26B1 present with a range of defects, including coronal craniosynostosis, calvarial mineralization defects and short limbs with long bone fusions (Laue, Pogoda et al. 2011). Finally, a triple mouse mutant of all three Cyp26 enzymes was embryonic lethal, with about 40% of severely affected mice showing full or partial duplication of the body axis, and highly elevated levels of RA signaling were observed throughout the embryo (Uehara, Yashiro et al. 2009). Such severe and broad phenotypes in these animals are observed not only due to teratogenic effects of excess RA, but also because of its interaction with other signaling pathways resulting in reduced Fibroblast Growth Factor (FGF) signaling, downregulation of Sonic Hedgehog (Shh) and increased Nodal expression (Helms, Kim et al. 1997, Duester 2008, Niederreither and Dollé 2008, Uehara, Yashiro et al. 2009, Cunningham, Zhao et al. 2013).

Xenopus embryos express Cyp26a1, b1 and c1, however only Cyp26a1 and c1 are detectable prior to neural tube closure (Hollemann, Chen et al. 1998, Chen, Pollet et al. 2001, Tanibe, Michiue et al. 2008). Cyp26c1 peaks around gastrulation and is expressed in the anterior neuroectoderm around neurula stage and persists up to the tailbud stage (Tanibe, Michiue et al. 2008, Yu, Umair et al. 2016). Cyp26c1 expression in this region is important for the accurate expression of genes involved in A-P neural patterning, and morpholino-mediated knockdown caused defects in head and body axis development (Yu, Umair et al. 2016). Expression of Cyp26a1 appears broadly at blastula stages and after gastrulation, becomes restricted to prospective anterior neuroectoderm, around the neural plate, and also the involuting mesoderm corresponding to the prechordal plate (Hollemann, Chen et al. 1998). Later in development, Cyp26a1 expression is visible in the first, second and third brachial arches. Cyp26a1 expression after gastrulation is also complementary to RALDH2 expression domain (Chen, Pollet et al. 2001), again emphasizing importance of local zones of RA regulation. Cyp26b1 is expressed at low levels, and is only detected at later stages (NF stage 25) in the hindbrain (Lynch, McEwan et al. 2011). In mice and Xenopus, Cyp26b1 is present in the developing limb bud and is important for limb outgrowth as well as regeneration (McEwan, Lynch et al. 2011), but not so much for anterior-posterior patterning (MacLean, Abu-Abed et al. 2001) (Table 1). The extent of functional redundancy of the three Cyp26 enzymes is unclear in Xenopus, but given the differential patterns of gene expression, it is likely that they are independently responsible for the development of separate structures. Altogether, this suggests that the correct development of anterior structures is particularly sensitive to RA levels, and employs local RA degradation for appropriate specification of craniofacial structures.

4.2- Cyp26 role in gradient formation

While both synthesis and degradation of RA are enzymatic reactions with complex auto-regulation, this review focuses mainly on the kinetics of regulated RA degradation as an essential means of establishing local RA concentrations. For a detailed discussion of the mechanisms of RA synthesis, see (Duester 1996, Kam, Deng et al. 2012, Kumar, Sandell et al. 2012, Kedishvili 2013).

RA signaling can act in an autocrine or paracrine manner, and cells within an organism can be broadly classified into three groups: RA-producing cells, which predominantly express ALDHs or RALDHs, RA-responsive cells that express CRBPs and nuclear RA receptors, and finally, RA-refractory cells where Cyp26 enzymes are highly expressed to catabolize cytosolic RA and clear the resulting metabolites from the cell (Figure 1). These properties of the cell can change over the course of development, and also spatially as domains of expression expand or shrink. RA-responsive cells, for example, can become non-responsive by upregulating Cyp26 enzymes and downregulating RA synthesizing enzymes, thus altering the RA “sensitivity” of different regions within the embryo. Additionally, RA-producing cells can also be RA-responsive (autocrine signaling), but RA-producing and RA-refractory cells typically form two distinct cell populations (Duester 2008).

One way to create defined sources of RA in the embryo is through spatial and temporal regulation of RA synthesizing enzymes. The numbers and classes of ALDHs or RALDHs expressed are not only different from species to species but also differ in different regions of the embryo itself (McCaffery and Dräger 1995, Niederreither, Fraulob et al. 2002), adding to the complexity of regulated signaling employed by RA. As an additional mechanism to create precise foci of RA signaling, the RA-producing domains are often juxtaposed with domains expressing Cyp26 (Hernandez, Putzke et al. 2007) (Swindell, Thaller et al. 1999). Existence of such domains is critical to produce RA gradients in the embryo that are essential for embryonic patterning and organogenesis, as several genes that contain RARE elements respond to different threshold levels of RA. For example, In Xenopus, the sequential spatial expression of genes of the Hox-2 cluster was shown to depend on their RA sensitivity (Dekker, Pannese et al. 1992). The expression of the six genes that comprise this cluster is carefully restricted spatially in segmental domains in the embryo and is turned on sequentially after gastrulation, with the anterior most genes induced first. Within each segment, the Hox gene is expressed in a posterior to anterior graded fashion. Treatment with exogenous RA disrupted the graded expression within each Hox segment, and strongly upregulated the anterior-most Hox-2 genes (Hox2.9, 2.7), while the induction of those expressed more posteriorly was moderate (Hox2.5)(Dekker, Pannese et al. 1992). These observations demonstrate that accessibility to RA is an important cue for the correct spatiotemporal expression of these genes. While this study applied a uniform dose of RA to the embryo, the fold induction of each gene varied significantly, further suggesting that the Hox-2 genes have intrinsically different RA sensitivities that are critical for this stringent expression to occur. Thus, a robust RA gradient is especially essential during early development for this coordinated gene expression.

Another mechanism to create restricted sources of RA is through the establishment of adjacent domains of RA synthesis and degradation. There are several examples of such regulation. In chick, quail and mouse embryos, RALDHs and Cyp26s have been found to be expressed in non-overlapping, often contiguous, domains (Swindell, Thaller et al. 1999),(Fujii, Sato et al. 1997, Niederreither, McCaffery et al. 1997, Reijntjes, Blentic et al. 2005). In Xenopus embryos, raldh2 is the primary RA synthesizing enzyme (Lynch, McEwan et al. 2011), and is expressed in the anterior neural plate, and the paraxial mesoderm (Chen, Pollet et al. 2001, Jaurena, Juraver-Geslin et al. 2015). During gastrulation, raldh2 and cyp26a1 are expressed in distinct but complementary domains — raldh2 is present in the trunk mesoderm, where as cyp26a1 is mainly restricted to the presumptive midbrain and hindrain (Chen, Pollet et al. 2001). These separate domains of expression are maintained along A-P body axis as development progressed, with RALDH2 restricted to the paraxial trunk mesoderm and cyp26a1 occupying the midbrain/forebrain boundary. Additionally, the anterior neural plate expression domain of RALDH2 sits anterior to the prospective cement gland region, where Cyp26 enzymes are expressed (Chen, Pollet et al. 2001).

Changes in these expression boundaries in response to exogenous RA are the likely cause of dramatic loss of anterior structures and axial truncations. Other examples of functional relevance of RA gradients calibrated by local, juxtaposed synthesis and degradation domains include those involved in the appropriate specification of photoreceptors in the developing retina in chick, mouse and human (Sakai, Luo et al. 2004, da Silva and Cepko). Moreover, adjacent raldh2 and cyp26a1 and c1 expression domains are essential for hindbrain patterning in mouse (Sirbu, Gresh et al. 2005). Cyp26a1 and c1 cooperate to generate an RA-free equatorial strip of cells in the mouse retina from the surrounding dorsal and ventral Raldh-rich regions, likely critical for invoking very specific gene expression in the three distinct zones (Sakai, Luo et al. 2004). Complementary raldh2 and cyp26a1 expression domains are also observed in the zebrafish tailbud, where they participate in establishing bilaterally symmetric somitogenesis (Kawakami, Raya et al. 2005). Distinct domains of local RA synthesis and degradation are also crucial for proper limb development, and correct timing of sex-specific initiation of meiosis (McCaffery, Posch et al. 1993, Cunningham and Duester 2015).

The significance of localized control of RA synthesis and degradation during development is emphasized by the conservation of this mode of regulation across vertebrates. Apart from the appropriate specification of photoreceptors in the retina, the mechanistic implications of this careful separation of RA synthesis and degradation domains during early embryogenesis remain unclear. Broadly however, it is beginning to emerge that this precise attenuation of RA levels in the anterior aspects of the embryo might be critical for the appropriate specification of the neural crest and cranial placode domains (Uehara, Yashiro et al. 2007, Jaurena, Juraver-Geslin et al. 2015), as excess RALDH2 or absence of Cyp26 enzymes results in anterior truncations.

While RA synthesis is subject to negative feedback regulation by endogenous RA (Strate, Min et al. 2009), the clearance of RA by Cyp26 enzymes is also utilized as a mechanism for feedback regulation of RA levels. This ensures the robustness of the RA gradient, that is, to minimize fluctuation in levels. This is attested foremost by the fact that Cyp26 enzymes were first identified in studies investigating genes upregulated upon RA exposure in mouse embryonic stem (ES) cells and zebrafish embryos (White, Guo et al. 1996), (Ray, Bain et al. 1997). The administration of exogenous RA to developing embryos was shown to upregulate the expression and spatial domains of Cyp26 enzymes in Xenopus, zebrafish, and Ciona, often with a concomitant downregulation of RA synthesis enzymes (Tanibe, Michiue et al. 2008),(Dobbs-McAuliffe, Zhao et al. 2004), (Ishibashi, Usami et al. 2005), (D’Aniello and Waxman 2015). Indeed, studies in zebrafish embryos demonstrated that the ability of RA to induce the expression of Cyp26 enzymes is the mechanism behind prolonged loss of RA after a teratogenic insult. The presence of three RAREs in Cyp26a1 promoter makes it highly responsive to an increase in RA levels (Hu, Tian et al. 2008). This enables Cyp26a1 to act as a “sink” for excess RA as well. An isolated insult of excess RA is capable of upregulating Cyp26a1 at not only the point of origin, but also in any neighboring cells into which the excess RA might diffuse (Rydeen, Voisin et al. 2015).

Interestingly however, endogenous RA does not appear to play a role in inducing Cyp26 expression under normal conditions (Dobbs-McAuliffe, Zhao et al. 2004). It is unclear how the distinction between endogenous and exogenous RA is made for the purposes of Cyp26 induction, but it is clear that Cyp26 activity is required for proper embryonic development, especially for patterning the A-P body axis, the hindbrain, and lens regeneration (Uehara, Yashiro et al. 2007), (Abu-Abed, Dollé et al. 2001), (Thomas and Henry 2014). For example, the upregulation of Cyp26a1 in zebrafish embryos led to the rostral expansion of hoxb5a and hoxb6a expression domains, thereby disrupting the hindbrain-spinal cord boundary, and causing an expansion of the spinal cord domain at the expense of the hindbrain (Emoto, Wada et al. 2005). The ability of RA to induce Cyp26 enzymes, coupled with the juxtposition of RA-degrading with RA-producing domains makes retinoid clearance a key mechanism to pattern the early embryo.

The above mechanisms — combined with additional tiers of regulation through interaction with other signaling pathways such as Wnt and Fgf signaling (Kudoh, Wilson et al. 2002), and through differential uptake of RA by varying the spatiotemporal expression profiles of CRABP isoforms (Dolle, Ruberte et al. 1990) (Gigueère 1994) (Whitney, Massaro et al. 1999) — together create a highly regulated RA gradient in the embryo. The resulting RA gradient is robust to perturbations and allows for long-range positional cues to be interpreted locally by individual cells through local degradation. Computational modeling has confirmed that a global gradient of RA can be adapted to several local niches in the embryo, while accounting for interactions with other signaling pathways, the changing shape of the embryo, and the changes in RA synthesis and uptake over time (White, Nie et al. 2007). Thus, intracellular RA concentration is precisely defined and maintained in a narrow range for a specific period and in a specific embryonic domain. Because of RA’s ability to auto-regulate its levels by controlling Cyp26 and raldh2 expression, an organism can also withstand some fluctuations in exogenous RA levels. Such carefully graded regulation that acts accurately and specifically over the course of development is highly unique to the RA signaling pathway. It is highly plausible that such sophisticated regulation provides significant evolutionary advantage to vertebrates, especially in the context of craniofacial development.

5- Kinetics of RA Degradation

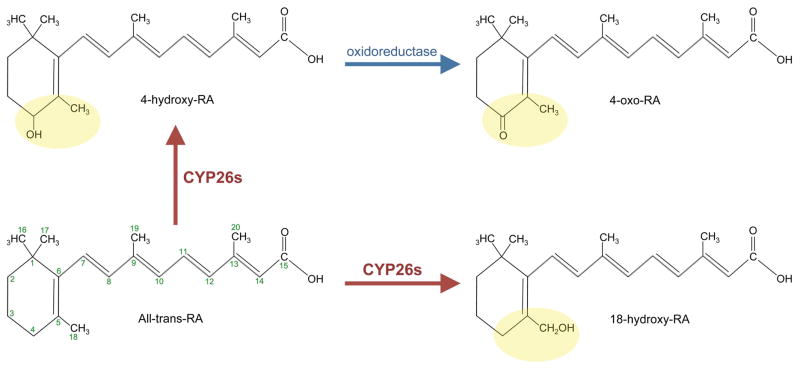

Cyp26 enzymes are rapid metabolizers of RA. All three Cyp26 enzymes are 4-hydroxylases, meaning that they catabolize RA by oxidative degradation mainly at the C-4 of the β-ionone ring and the C-18 (Figure 2) to generate a mixture of polar metabolites such as 4-oxo-RA, 4-OH-RA, and 18-OH-RA, that can be excreted from the cell (White, Ramshaw et al. 2000, Chithalen, Luu et al. 2002). In fact, in these initial studies RA metabolites were often quantified from plasma, or obtained during in vitro reactions. However, given that RA is degraded in several local domains in tissues, the systemic concentration of RA in human plasma is not an accurate indicator of overall RA homeostasis and metabolism (Stevison, Jing et al. 2015). Cyp26 enzymes need a membrane environment for activity due to their requirement for P450 reductase, present in the ER membrane (Lutz, Dixit et al. 2009, Stevison, Jing et al. 2015). Hence their activity is often assessed using recombinant proteins in preparations of microsomal fractions isolated from tissues and cell lines. This is a powerful way to assess kinetics, as it can test one enzyme at a time without confounding contributors, and provide specific measurements on the efficacy of various inhibitors.

Figure 2. Retinoic acid metabolism and degradation.

A schematic representation of catabolism of RA by Cyp26 enzymes. RA contains a β-ionone ring (C1–C6) conjugated to a polyene hydrocarbon chain (C7–C15). Cyp26 enzymes act mainly on C4–C5 and C18 (highlighted in yellow) of the β-ionone ring of all-trans RA (bottom left) to generated polar metabolites. The main metabolites generated by all three Cyp26 enzymes are 4-hydroxy RA (top left), which gets converted to 4-oxo RA by an unknown oxidoreductase (blue arrow, top right), and 18-hydroxy RA (bottom right).

Among the cytochrome P450 enzymes, the Cyp26 family has the highest affinity for atRA and is capable of swift catalysis, achieving half the maximum reaction velocity at low concentrations of less than 100 nM RA (thus Km <100nM RA) (Topletz, Thatcher et al. 2012). Cyp26s can metabolize atRA, as well as the 9-cis and 13-cis forms generated by atRA isomerization, but atRA tends to be the preferred substrate in this order: atRA > 9-cis-RA > 13-cis-RA (White, Ramshaw et al. 2000). A comparison of the kinetics of recombinant Cyp26a1 and b1 showed that despite sequence divergence, they possess similar properties, and metabolize atRA primarily to 4-OH-RA, and 18-OH-RA, followed by further hydroxylation of the products (Topletz, Thatcher et al. 2012). The same study showed that while Cyp26a1 has a lower affinity for atRA, it performs catalysis at a faster rate and is overall ~20 fold more efficient in degrading RA than Cyp26b1. Both enzymes degrade 9-cis-RA with low efficiency. Cyp26c1 appears catalytically different from Cyp26a1 and b1, and also has an expression pattern distinct from both (see previous section). Under certain conditions, Cyp26c1 binds atRA with lower affinity than Cyp26a1 and b1, but unlike the other two enzymes, it has broader substrate specificity and binds 9-cis-RA with ~100 fold greater affinity to metabolize it (Taimi, Helvig et al. 2004). The biological significance of 9-cis-RA and this unique property of Cyp26c1 is unclear, but since some RXRs recognize 9-cis-RA as a ligand (Montplaisir, Lan et al. 2002), it serves as a potential mechanism for gene expression regulation. Additionally, Cyp26c1 is far less susceptible to the broad Cyp26 enzyme inhibitor ketoconazole, due its low affinity for the compound (Taimi, Helvig et al. 2004). Overall, Cyp26a1 is the most efficient at clearing atRA, reaching a Km of ~9.5 nM (Lutz, Dixit et al. 2009) and continues to be the primary metabolizer of RA in adult tissues. Further studies are needed to firmly establish the catalysis parameters for Cyp26b1 and c1, including a simultaneous comparison of atRA and 9-cis-RA substrates.

Finally, there is evidence to suggest that some metabolites of atRA, especially those generated by epoxidation (4-oxo-RA and 5,6 epoxy-RA), have some biological activity in directing positional information in developing Xenopus embryos, and proliferation of growth-arrested spermatogonia in VAD mouse testis (Pijnappel, Hendriks et al. 1993, Gaemers, van Pelt et al. 1996). However, genetic studies using Cyp26a1 KO mice have suggested that these compounds are not directly involved in RA signaling during embryonic development, as the resulting defects could be rescued by a concomitant heterozygous deletion of RA-synthesizing Aldh1a2 (Niederreither, Abu-Abed et al. 2002). This study concluded that the defects observed in Cyp26a1 KO mice were due to excess RA signaling rather than from the absence of metabolite signaling and that reducing RA synthesis mitigates the teratogenic effect of excess RA. However, the biological role of retinoid metabolites and their functional interaction with retinoid receptors cannot be completely excluded until retinoid metabolites are carefully tested in a system similar to VAD quails and mice. Sustained research efforts in this area will inform how local degradation of RA through different catalytic means contributes to precision and specificity in establishing major developmental programs.

6- RA signaling in neural crest and cranial placodes formation

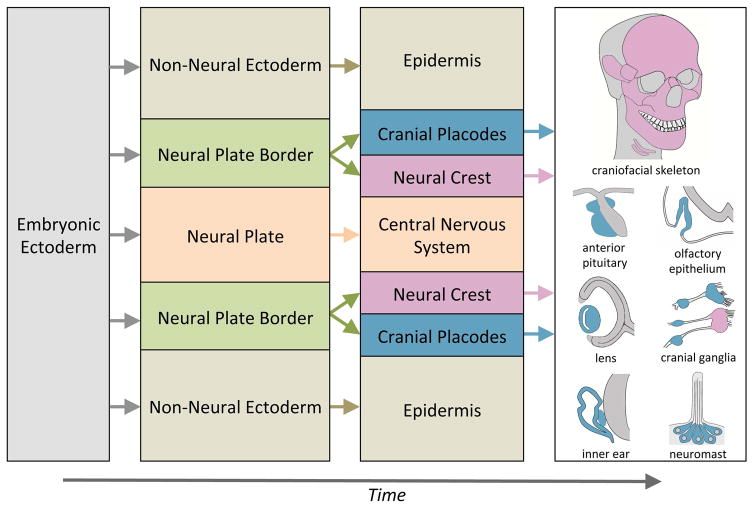

The role of RA as a critical morphogen during development is especially interesting in the context of specification of craniofacial structures. Anteriorly, the vertebrate embryo develops a complex craniofacial skeleton associated with sensory organs, both systems largely derived from two embryonic cell lineages the neural crest and cranial placodes, respectively (Figure 3). At the end of gastrulation both cell populations arise form a region of the ectoderm at the boundary between the neural plate (NP; prospective central nervous system) and the non-neural ectoderm (NE; future epidermis) known as the neural plate border (NPB) (Milet and Monsoro-Burq, 2012, Saint-Jeannet and Moody, 2014). The NPB arises as a consequence of interactions between cells from NP and NE, and the underlying mesoderm (Basch, García-Castro et al. 2004, Bae and Saint-Jeannet 2014). Grafting experiments in Xenopus and chick have shown that the juxtaposition of NP and NE can generate cells with neural crest and/or placode identity at the boundary between the two tissues (Selleck and Bronner-Fraser 1995, Mancilla and Mayor 1996, Glavic, Maris Honoré et al. 2004, Ahrens and Schlosser 2005). In chick, this progressive subdivision of the ectoderm begins with the establishment of these domains at the blastula stage (Patthey and Gunhaga 2011). In Xenopus, the process follows the same progression but starts around gastrula stage. It is important to note, however, that most uncommitted progenitors in NPB become specified into either neural crest or cranial placodes by the end of neurulation through the activation of specific subsets of transcription factors unique to each cell type (see (Roellig, Tan-Cabugao et al. 2017) and reviewed in (Basch, García-Castro et al. 2004, Sauka-Spengler and Bronner-Fraser 2008, Patthey and Gunhaga 2011, Milet and Monsoro-Burq 2012, Bae and Saint-Jeannet 2014).

Figure 3. Major subdivisions of the embryonic ectoderm and contributions of the neural crest and cranial placodes to craniofacial structures.

At the end of gastrulation, the embryonic ectoderm is subdivided into three domains: the non-neuronal ectoderm, neural plate and the neural plate border. The non-neural ectoderm and neural plate give rise to the epidermis and central nervous system (CNS), respectively. The neural plate border develops into two cell populations the neural crest and cranial placodes. In the head region the neural crest (red) contributes to the craniofacial skeleton and a subset of cranial ganglia. The cranial placodes (blue) differentiate into the anterior pituitary, optic lens, inner ear, olfactory epithelium and cranial ganglia, as well as neuromasts of the lateral line in anamniotes.

The progressive fate-restriction of NPB region requires input from several signaling pathways. In amphibians and amniotes, the organizer and the hypoblast, respectively, serves as an important source of spatial cues that promote fate specification. Mitigation of BMP signaling by antagonists Noggin, Chordin and Follistatin serves as an important driver of neural differentiation in the dorsal ectoderm (reviewed in (Wilson and Edlund 2001)). Experimental evidence in amniotes to date suggests that RA is not required for neural induction in the embryo (Molotkova, Molotkov et al. 2005), but these observations remain to be extended to other species. The current model suggests that regions with low BMP activity will form NP, high BMP levels specify the epidermis, and the region with medium levels of BMP will form the NPB (Marchant, Linker et al. 1998). However, BMP activity alone is not sufficient for further fate-restriction (LaBonne and Bronner-Fraser 1998). For further patterning of NPB into neural crest and cranial placode, posteriorizing signals such as Wnt and FGF signaling are also required (Saint-Jeannet, He et al. 1997, Chang and Hemmati-Brivanlou 1998, LaBonne and Bronner-Fraser 1998, Patthey, Edlund et al. 2009). There are some differences between species in the requirement of these signaling pathways and the timing at which neural induction is initiated (Wilson and Edlund 2001). Because embryonic synthesis of RA doesn’t begin until late blastula/early gastrula stages (Chen, Huang et al. 1994, Ang, Deltour et al. 1996), it is difficult to ascertain a clear role for RA during the early stages, including the levels of maternal RA that may be present, to inform specification events. However, as development progresses through the end of gastrulation when NPB forms, RA begins to emerge as a key regulator for neural crest and cranial placode formation, and A-P patterning.

6.1-Neural crest

Neural crest induction has been extensively studied in fish, chick and frogs (see reviews (Knecht and Bronner-Fraser 2002, Basch, García-Castro et al. 2004, Bae and Saint-Jeannet 2014)). Several aspects of neural crest development have been shown to depend on RA signaling. The expression of one of the earliest markers of neural crest identity, Gbx2, is regulated by both RA and Fgf8 in mouse and Xenopus (von Bubnoff, Schmidt et al. 1996, Li, Lao et al. 2005). The critical role of RA in survival and maintenance of neural crest cells is illustrated by studies examining RA teratogenicity in embryonic development. They revealed that the structures affected in RAE are primarily derivatives of the cranial neural crest. Exposure to excess RA in early stage mouse embryos resulted in posteriorization of the hindbrain, whereas later exposure resulted in malformations in the first and second branchial arches (Goulding and Pratt 1986, Marshall, Nonchev et al. 1992).

Experiments in Xenopus involving exposure of late-gastrula stage anterior neural folds to FGF, Wnt8 or RA, revealed that RA results in the suppression of the anterior marker ag1 with concomitant induction of neural crest-marker snai2, and is necessary for imposing a posterior fate on the developing NP that is essential for neural crest formation (Villanueva, Glavic et al. 2002). Interestingly, while Wnt, FGF and RA were each able to posteriorize the anterior neural fold to induce snai2 expression, removing one of these factors in vivo inhibited the process. In particular, what distinguished RA signaling from the other two was that manipulations of RA signaling affected the anterior and posterior boundaries of the neural crest region differentially (Villanueva, Glavic et al. 2002). This suggests that these pathways work in concert without being redundant and are required in a specific cascade of signaling events that is calibrated for the spatial orientation of these embryonic domains. In zebrafish embryos, Cyp26a overexpression suppressed, while knockdown expanded the expression of posterior genes. It has been proposed that the posteriorization of the neural ectoderm is achieved in a two-step process: first Wnt and FGF signals suppress anterior genes in an RA-independent fashion, and then the expression of posterior genes is activated in an RA-dependent manner through suppression of Cyp26a expression by FGF and Wnt (Kudoh, Wilson et al. 2002). Thus, the role of RA in neural crest formation appears to be indirect through its regulation of FGF signaling, and more specifically Fgf8.

This concept is supported by other studies examining the impact of RA signaling on neural crest development. In vitro experiments involving teratogenic RA exposure in cultured mouse neural crest cells showed that RA alters the gene expression profile of neural crest cells, with over a third of all RA-responsive genes being associated with major signaling pathways (Williams, Mear et al. 2004). Exposing pregnant mice to exogenous RA through a single administration at the developmental stage coinciding with the onset of neural crest migration was sufficient to transform the lower jaw into upper jaw like structures (Abe, Maeda et al. 2008). Further analyses revealed these morphological changes were preceded by a reduction in Fgf8 expression in the first pharyngeal arch. Interestingly, Fgf8 expression was recovered after removal of excess RA (Abe, Maeda et al. 2008). Together, these findings suggest that effects of disrupted or excess RA signaling are in part an indirect consequence of changes in FGF signaling. Such changes are considered a hallmark of the posteriorizing nature of RA signaling, which is critical for the induction of neural crest in vertebrates.

It is unclear whether RA as a direct role in neural crest induction. RARs and RXRs are expressed during early embryogenesis in zebrafish, Xenopus and mice, most prominently in the presumptive hindbrain and during somitogenesis and axis extension (Dollé 2009). Whether these receptors are expressed at the NBP to allow for direct RA signaling is unclear. However, it has been shown that the development of anterior structures such as the forebrain and the cement gland in Xenopus was dependent on active repression by RARs. Using an RAR-antagonist, AGN193109, to increase this repression caused an anterior expansion of the neural plate (Koide, Downes et al. 2001). Conversely, antisense-morpholino mediated knockdown of RARα resulted in reduced cement gland and truncated forebrain. The underlying mechanism for these defects is unclear and it is not known whether the different RAR isoforms in Xenopus act redundantly. These findings are however consistent with existing models suggesting that attenuated RA signaling is required to promote development of anterior structures.

Excess RA also disrupts neural crest migration, in such a way that anterior hindbrain neural crest cells migrated ectopically to the second branchial arch, while the preotic hindbrain neural crest cells exhibited aberrant anterior migration (Lee, Osumi-Yamashita et al. 1995). These disruptions were attributed to changes in Hox gene expression that are known to be highly segment-specific and highly responsive to RA. Vitamin A-deficient quails have proven to be a useful model to understand the role of RA in early embryogenesis (Maden, Gale et al. 1996). The eggs (including yolk) and embryonic tissues lack retinoids and show apoptosis of neural crest cells, resulting in improper formation of the branchial arches. Zebrafish neckless mutants carrying an inactivating mutation in raldh2 exhibit a range of phenotypes, including shortening of the A-P axis anterior to somites, disruptions in Hox gene expression, and apoptosis of neural crest cells in the posterior hindbrain (Begemann and Meyer 2001). A more recent study in zebrafish showed that RA regulates survival and early neural crest cell migration. In embryos with disrupted RA signaling, neural crest cells from the rhombencephalon failed to populate the branchial arches, and those from the mesencephalon and prosencephalon did not properly target the craniofacial region, leading to malformations of the ocular structures (Chawla, Schley et al. 2016). Therefore, in addition to its posteriorizing role to set up the neural plate border, RA appears to play a vital role in neural crest migration and survival.. It is indirectly critical for eye development, a structure that requires important positional cues from the neural crest for development of the extraocular muscle and correct morphogenetic movements associated with optic cup formation (Molotkov, Molotkova et al. 2006, Matt, Ghyselinck et al. 2008).

6.2-Cranial placodes

All cranial placode progenitors arise from a common territory that borders the anterior neural plate known as the PPR, which is then progressively subdivided along the A-P axis into distinct domains in which cells adopt fates characteristic for each sensory placode: the adenohypophyseal, olfactory, lens, trigeminal, epibranchial, otic and lateral line (in anamniotes) placodes (Figure 3). The paired sensory organs originate in the lens, otic and olfactory placodes, whereas the epibranchial and trigeminal placodes contribute sensory neurons to a subset of the cranial nerves and the trigeminal ganglion, respectively (Baker, O’Neill et al. 2008). The trigeminal placode contributes to the distal region of the Vth cranial ganglion, relaying cutaneous sensations from the head to the CNS (McCabe, Sechrist et al. 2009). For detailed reviews on specification of the PPR and its differentiation into individual placodes with unique identities, see these comprehensive reviews (Baker and Bronner-Fraser 2001, Schlosser 2006, Baker, O’Neill et al. 2008, Schlosser 2010, Saint-Jeannet and Moody 2014, Moody and LaMantia 2015).

Very few studies have evaluated the role of RA signaling in the context of PPR formation. It is well established that a combination of FGF signaling and attenuation of both BMP and Wnt signaling are involved in the induction of the PPR at the end of gastrulation (Litsiou, Hanson et al. 2005). In Xenopus, the transcription factor Zic1 is activated in the anterior neural plate in response to these signaling events. Zic1 is both necessary and sufficient to promote placodal fate by regulating the expression of several PPR-specific genes, including Six1 and Eya1 (Hong and Saint-Jeannet 2007). In an effort to understand the regulatory cascade downstream of Zic1 a microarray analysis was performed in Xenopus animal cap explants to identify the targets of Zic1 during PPR formation. The major targets of Zic1 were found to be involved in RA signaling, transport and degradation including raldh2, and RA transporter lpdgs (lipocalin-type prostaglandin D2 synthase) and cyp26c1. Subsequent knockdown experiments and studies involving exogenous RA-treated embryos showed that PPR formation requires both RA signaling in the anterior neural plate and RA transport to the site of the prospective PPR (Hong and Saint-Jeannet 2007, Jaurena, Juraver-Geslin et al. 2015). This study not only demonstrated that RA is involved in promoting placodal identity, but also identified a localized anterior source of RA in the neural plate that is critical for the formation of key structures of the vertebrate head.

Another study focusing on signaling through RAR, specifically RARα2, has shown that RARα2 signaling was essential to restrict the posterior-lateral boundary of the PPR (Janesick, Shiotsugu et al. 2012). RARα2 morphant embryos exhibited reduced expression of Six1 and Eya1 in the posterior domain of the PPR. A microarray screen to identify the genes mediating RAR signaling identified two RA-responsive genes, the T-box transcription factor Tbx1 and a member of the Ripply/Bowline family, Ripply 3 (Arima, Shiotsugu et al. 2005, Janesick, Shiotsugu et al. 2012). Both Tbx1 and Ripply3 are expressed in PPR and upregulated by RA, and knockdown of either one of these genes disrupted the spatial domains of PPR genes, Six1 and Eya1 (Janesick, Shiotsugu et al. 2012). While the evidence to support a role for RA in placode formation is unambiguous, mechanistic details on how RA is able to orchestrate the formation of such complex structures is unclear. Future work to identify specific, dose and position-specific roles for RA in the development of placodes as well as their target genes will provide tremendous insight into the fine-tuned regulation of this developmental program.

6.2.1-Lens placodes

A potential role of RA in formation and specification of individual cranial placodes from the PPR is relatively understudied. It is perhaps best described in the context of lens and otic placode development. The lens placode invaginates from the surface ectoderm to form the lens of the eyes. Using RARE-β-galactosidase reporters, RA signaling activity was detected in the mouse retina and lens ectoderm before neural tube closure, coinciding with the beginning of lens induction (Enwright III and Grainger 2000). In Pax6 mutant mice, which have small eyes/lens, the same reporter constructs indicated that RA signaling was drastically inhibited in the anterior CNS and placodal regions, whereas the posterior CNS exhibited normal RA signaling. In addition, there is evidence to support that RA causes accumulation of lens proteins by activating the αβ-crystallin gene through RAR/RXR heterodimers (Gopal-Srivastava, Cvekl et al. 1998). RA signaling in this context is primarily paracrine with the RA source being the optic vesicle, the future retina. Interestingly, RA also has an autocrine activity during eye development since the invagination of the optic vesicle into an optic cup dependent on RA synthesized by the optic vesicle (Mic, Molotkov et al. 2004). The transcription factor TFAP-2α, which is expressed in the lens placode and is essential for the morphogenesis of the lens vesicle, is also an RA-responsive gene (West-Mays, Zhang et al. 1999).

6.2.2-Otic placodes

The otic placode invaginates into an otic cup which pinches off from the ectoderm to form the otic vesicle, precursor of the inner ear. In the chick, the future otic placode is located between domains expressing raldh2 and Cyp26 enzymes (Blentic, Gale et al. 2003, Reijntjes, Gale et al. 2004, Bok, Raft et al. 2011). Application of RA-soaked beads to the mesenchyme anterior to the otic cup reduces the size of the otocyst and the expression of anterior neurosensory markers. Furthermore, the use of RARE-LacZ reporter constructs illustrated that the responsiveness of otic epithelium to RA diminishes as development progresses (Bok, Raft et al. 2011). In this report, different concentrations of RA were found to be necessary and sufficient to posteriorize the otocyst and were essential for appropriate anterior gene expression in the otic placode. RA is also synthesized in the mouse otic vesicle, which expresses raldh3 (Mic, Molotkov et al. 2000). In zebrafish, RA and FGF signaling are essential for formation of the otic neurogenesis domain and production of otic neuroblasts (Maier and Whitfield 2014). Loss of RA signaling through knockdown of RALDH enzymes or pharmacological inhibition resulted in hypoplastic otocysts in mice and zebrafish (Niederreither, Subbarayan et al. 1999, Whitfield, Riley et al. 2002). However, upon diminished RA signaling, such as in vitamin A deficiency, ectopic supernumerary and dysmorphic otic vesicles were generated (White, Highland et al. 2000). These seemingly disparate phenotypes are consistent with reports showing that absence or excess RA may result in similar outcomes (Uehara, Yashiro et al. 2007, Jaurena, Juraver-Geslin et al. 2015). A mechanism for these observations was identified subsequently, wherein weak upregulation of RA signaling expands the expression of foxi1, a gene required for competence to adopt otic fate, in the entire PPR. Conversely loss of RA signaling reduces fgf3 and wnt8 expression without affecting foxi1 expression, which delayed otic induction and reduced maintenance of otic fate (Hans and Westerfield 2007). This report also showed that increasing FGF signaling in RA-depleted embryos can restore otic induction but not maintenance of otic progenitors. Zebrafish embryos exposed to RA, show an expansion of the otic marker pax8 along with formation of supernumerary and ectopic otic vesicles, both phenotypes attributed to defective FGF signaling (Phillips, Bolding et al. 2001). Thus, changes in otic vesicle formation observed upon alterations in RA signaling are considered to be secondary to changes in FGF signaling.

This role of RA in otic placode specification appears to be well conserved across species. In the ascidian Ciona intestinalis, RA is required for the expression of Hox1 in the epidermal ectoderm. This in turn is necessary for the correct specification of the atrial siphon placode, an invertebrate homolog of the otic placode (Sasakura, Kanda et al. 2012). Recently, single-cell analysis of human otic lineages derived from pluripotent stem cells revealed that RA treatment was essential for the induction of FGF-dependent early otic markers, and posterior placodal fates by upregulating PAX2 and PAX8 expression (Ealy, Ellwanger et al. 2016).

6.2.3- Olfactory placodes

The olfactory placode invaginate as a pit to form the olfactory epithelium that lines part of the nasal cavity. The olfactory epithelium synthesizes RA primarily via raldh3, though in mice it expresses all three RALDHs (Peluso, Jang et al. 2012). While RA is not required for the induction of this neuroepithelium, it is needed for maintaining the progenitor pool so it can proceed to subsequent neurogenesis (Paschaki, Cammas et al. 2013). Depletion of RA in both chick and mice resulted in a failure of olfactory precursors to renew and differentiate into olfactory receptor neurons. Interestingly, the patterning cues for the olfactory placode are provided by adjacent neural crest cells. Experiments in mouse embryos have shown that neural crest contributes to the fronto-nasal mesenchyme that surrounds the olfactory placode at later stages, and this mesenchyme serves as a source of RA for patterning the placode through expression of raldh2 (Bhasin, Maynard et al. 2003). The olfactory epithelium itself produces raldh3, indicating that there are two local sources of RA that are critical for specification (Li, Wagner et al. 2000). Interestingly, raldh2 knockout embryos do not express raldh3, and lack the olfactory placodes, suggesting that while the two RA sources are distinct, the production of RA in the olfactory epithelium depends on RALDH2 activity in the front-nasal mesenchyme (Mic, Haselbeck et al. 2002).

6.2.4-Epibranchial and lateral line placodes

The epibranichial placode contributes sensory neurons to the distal regions of the VIIth, IXth and Xth cranial nerves that innervate the mouth cavity, the external ear, the heart and respiratory system (Steventon, Mayor et al. 2014). The molecular mechanisms of epibranchial placode specification are poorly understood, but a requirement for FGF signaling in this process has been documented (Sun, Dee et al. 2007). In chick embryos, an enzyme from the Cyp p450 family, Cyp1B1, which has RA synthesizing, and no RA degradation activity, has been shown to regulate neurogenesis in epibranchial placodes (Chambers, Wilson et al. 2007). Overexpression of Cyp1B1 disrupted the expression of Phox2a, a neuronal cell marker, in these placodes, phenocopying exposure to excess RA.

The lateral line system is a mechanosensory and electroreceptive sensory organ found in fish and amphibians, derived from a series of paired lateral line placodes (LLP) in the head (Baker and Bronner-Fraser 2001). Zebrafish has anterior and posterior LLP which have different signaling requirements (Nikaido, Navajas Acedo et al. 2017). Inhibition of RA synthesis by DEAB (4-Diethylaminobenzaldehyde), a pharmacological antagonist of aldh2, caused loss of posterior LLP at later stages. Interference with RA production during gastrulation, resulted in ectopic activation of FGF signaling which also impeded posterior LLP development. These observations suggest that the anterior and posterior LLP employ different molecular programs for subsequent specification and that their positional identity is modulated by RA and FGF signaling. Wnt signaling is also important in development of LLP although its specific role is less clear. The posterior LLP itself segregates into primary and secondary placodes, which are both formed in response to RA signaling around gastrulation, and DEAB treatment reduces the formation of neuromasts and ganglia formed by the posterior LLP (Sarrazin, Nuñez et al. 2010). Excess RA treatment in axolotl lateral line reduces the production of neuromasts and also alters their organization in a dose dependent fashion (Gibbs and Northcutt 2004).

6.2.5-Adenohypophyseal placode

The adenhypohyseal placode (AHP) invaginates into the roof of the mouth as Rathke’s pouch to form the hormone-producing secretory cells of the anterior pituitary (Baker and Bronner-Fraser 2001, Asa and Ezzat 2004). Substantial research has been done on the mechanisms of AHP induction, but evidence for a role of RA in this process is limited. RALDH2 KO mouse embryos failed to develop Rathke’s pouch, and displayed concomitant reduction of Fgf8 expression in facial surface ectoderm (Ribes, Wang et al. 2006) suggesting that RA is essential for appropriate development of the pituitary. In chick embryos RALDH3 is expressed in the anterior region of Rathke’s pouch (Sjödal and Gunhaga 2008). In Vitamin A deficient quail embryos the adehohypophyseal placode fails to invaginate and thus, Rathke’s pouch does not form (Maden, Gale et al. 1996). This was accompanied by downregulation of Shh, Bmp2 and Fgf8 expression. These findings are consistent with the phenotypes of Raldh2-deficient mice and previous studies demonstrating that RA cross regulates FGF and other signaling pathways.

Collectively, the above studies highlight the fundamental role of RA signaling in the development of craniofacial structures. Moving forward, some of the critical questions to be tackled in the field will center on 1) determining the mechanisms by which RA orchestrates such complex and diverse outcomes, 2) the gene expression changes it introduces and 3) the levels at which it operates in individual tissues in vivo. With the latest advances in metabolomics, it has become possible to accurately assess the levels of RA and its metabolites in tissues using a variety of methods and will likely provide novel insights into signaling by retinoids and their byproducts.

7- Detection methods for retinoids

Given the importance of RA in establishing unique fate specification gradients, it is imperative to quantify the endogenous levels of RA existing in each specific biological system within an organism. RA cannot be directly visualized histologically, given its non-peptidic, amphipathic nature and diffusibility (Ababon, Li et al. 2016). Traditional methods to quantify endogenous RA levels have relied on reporter-based assays, where the RARE of a gene of interest is fused to either a LacZ or a luciferase construct. This can be done in the whole animal or a tissue of interest using stereotactic injections, and the activation of these reporters serves as an indirect measure of the endogenous levels of RA (Sakai and Dräger 2010). While this method is commonly used, it cannot specifically indicate the location of the RA source or quantify precise amounts, and relies heavily on the sensitivity of the reporter.

Recently, a few other strategies have been devised to quantify endogenous RA. The fact that RA binds to CRABP-I with high affinity has been harnessed into a detection method where a fluorescent residue is covalently attached to CRABP-I in a region that undergoes a conformational change upon RA binding (Donato and Noy 2010). The resulting change in fluorescence can be measured in real time and extrapolated to yield endogenous RA concentrations. This method was shown to be successful in cell culture, but relies on the introduction of artificial fusion proteins into the biological system for RA measurement. Yet another method employs ligand-binding domains of RA receptors that are modified to contain cyan- and yellow-fluorescent protein (CFP, YFP) residues (Shimozono, Iimura et al. 2013). Binding of RA to the receptor causes fluorescence resonance energy transfer (FRET) that indicates the levels of RA bound to the receptor. This method has been successfully used for live imaging of native RA levels in zebrafish embryos. However, despite their sophistication, these methods are limited to indirect detection of net amounts of RA rather than direct, dynamic monitoring. Additionally, they do not necessarily reflect the endogenous RA levels as they rely on the sensitivity of the RARE element or the binding efficiency of RA to CRABP and RARs. The sole direct method of RA detection is through high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC).

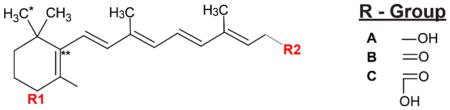

The chemical structure of retinoids makes them amenable for chromatographic detection. Structurally, all retinoids possess a non-aromatic β-ionone ring linked to four isoprenoid units with a series of conjugated double bonds. Additionally, they each possess a sidechain R-group consisting of either an alcohol, aldehyde, carboxylic acid or ester group, which alters the function of the retinoid (Gundersen and Blomhoff 2001). The electron-rich conjugated double bonds render retinoids well-suited for ultraviolet-based detection (UV) due to strong light absorbance in this range. However, in complex samples such as biological extracts the precise spectrophotometric discrimination of various retinoid molecular species becomes a challenge. In addition to their structural similarity, retinoids are present in very low concentrations in tissues and are sensitive to light and oxidation (Kane and Napoli 2010). Due to their electron-rich nature, they are frequently subject to isomerization and degradation during the extraction process, which can be minimized by performing the isolation under red light. For a detailed review of the chemistry of retinoids and isolation procedures, see (Gundersen and Blomhoff 2001).

Several groups have successfully implemented HPLC as the primary modality of their analyses. Published methods generally rely on either reverse- or normal-phase separation, which differ in speed and detection limit of retinoids. As with any quantitative assay, internal standards are used in HPLC as a reference to create accurate and precise quantification. For quantification of RA metabolites, commercially available pure retinoids such as 9-cis-RA, 13-cis-RA and at-RA are used as reference compounds. HPLC based methods have enabled rapid (~20 min) and sensitive (~10–40 fM detection limit) methods for detection of retinoids in serum and tissue (Kane, Chen et al. 2005, Arnold, Amory et al. 2012). This specificity and speed is possible because liquid chromatography separates the complex sample into individual components through time, and is a proven strategy for reliable analyses.

Most commonly, retinoid structures are best separated through reverse-phase HPLC on a non-polar stationary phase, which offers higher reproducibility and better separation of retinoid components (Craft 1992). However, as with all approaches, HPLC has its limitations. Most HPLC methods only report quantification of a few specific retinoids and the identity of the compound is primarily determined by comparing its retention time to that of a reference standard. The other way to improve accuracy is through the use of tailored sample extraction methods, such as solid-phase extraction. This method separates the components of a biological lysate based on their physical and chemical properties, thus decreasing the complexity of the mixture before it is loaded on the HPLC column. Without the use of the proper extraction methods or the availability of pure commercial standards, this technique can present significant limitations.

Endogenous retinoids vary greatly in concentration within a biological sample, spanning six orders of magnitude. In serum or plasma, retinoids are reported between ~1 and 10 pmol/mL while sub-fmol detection is required for tissue measurements where investigators are often sampled-limited (Kane and Napoli 2010, Kane 2012). Therefore, any HPLC methods, especially those relying on absorbance, must first be validated for that specific biological sample and referenced to pure, commercially synthesized standards. Recent advances, such as ultra-high pressure liquid chromatography (UPLC), have helped improve the chromatographic resolution of retinoids while providing greater sensitivity and throughput (Kane 2012, Gumustas, Kurbanoglu et al. 2013). In combination with more advanced detection systems, this approach is by far the best option for retinoid detection. In order to achieve isomeric separation at high resolution, as well as accurate quantification of levels of RA and its metabolites, mass spectrometry analysis has been coupled to HPLC as a robust method of direct RA quantification. Many hybrid methods have been used with varying levels of success to measure retinoids, which include LC-MS/MS, LC-MS, HPLC-UV/vis, GC-MS, UPLC-MS, UPLC-MS/MS (Lai and Franke 2013).

The coupling of a mass spectrometer to the front-end separation techniques discussed above allows for time-dependent separation and specific detection of unique mass signatures (retinoic structures) within complex biological samples (Priego Capote, Jiménez et al. 2007, Kane and Napoli 2010, Midttun and Ueland 2011, Kane 2012). One of the key steps for sensitive mass spectrometry (MS) detection is the conversion of compounds in the solution phase to charged particles in the gas phase. To this end, retinoids have been ionized for MS with electrospray ionization (ESI), atmospheric pressure chemical ionization (APCI)(Wang, Chang et al. 2001, McCaffery, Evans et al. 2002, Kane, Chen et al. 2005) and matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization (MALDI)(Wingerath, Kirsch et al. 1999). Retinoic acid is more efficiently detected in positive ion mode as it presents favorable ionization efficiency due to its conjugated structure and presence of a carboxylic group (Kane, Chen et al. 2005). However, negative ion mode has proven useful for polar metabolites produced from retinoic acid catabolism (Blumberg, Bolado et al. 1996).

Subsequently, anions or cations formed in the source are then steered to a mass analyzer, i.e., a quadrupole mass filter or ion trap, for the detection of its mass-to-charge ratio (m/z), thus obtaining the MS1 spectra. Each unique compound’s signal is quantified by its m/z and intensity, and each unique ionized compound can also be identified by a specific peak in these spectra. Retinoid quantification is carried out using an external standard curve generated by known pure standards, where the arbitrary MS intensity is proportional to an absolute concentration. Such MS1 measurements offer highly sensitive detection, and better structural specificity, but still rely heavily on retention time for structural confirmation. As a second step, most mass spectrometers also acquire tandem mass spectra (MS2), which provides a higher level of confidence that the correct compound is identified. In an MS2 scan, a putative retinoid ion peak from an MS1 scan is isolated and fragmented to generate a structure-specific pattern of m/z markers at a given energy (Kind, Tsugawa et al. 2017). These fragment ions can be detected in a targeted fashion (narrow tolerance around known fragment) or in an untargeted fashion. In combination with an accurate mass, an MS2 scan provides powerful structural confirmation for specific retinoids and typically, both MS1 and MS2 scans are integrated for precise quantitation of metabolites. The conserved β-ionone ring generates a characteristic pattern for all retinoids, while the varying R-groups give each retinoid class a unique accurate mass (Table 2). Such tandem data can therefore be used to confirm the structure of common retinoid targets and potentially investigate novel derivatives.

Table 2.

List of natural retinoid species and their chemical formulae.

| |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Retinoids | R1 | R2 | Formulae |

| 3,4-didehydroretinoic acid | - | C | C20H26O2 |

| All-trans retinoic acid | - | C | C20H28O2 |

| 9-cis retinoic acid | - | C | C20H28O2 |

| All-trans-4-oxoretinoic acid | B | C | C20H26O3 |

| All-trans-4-hydroxyretinoic acid | A | C | C20H28O3 |

| 18-hydroxyretinoic acid | A* | C | C20H28O3 |

| Retinol | - | A | C20H30O |

| All-trans-4-hydroxyretinol | A | A | C20H30O2 |

| All-trans-4-oxoretinol | B | A | C20H28O2 |

| Retinal | - | B | C20H28O |

Formulae correspond to neutral retinoid species. R1 and R2 are the variable putative ring and tail fragments in each retinoid. They are listed under R-Group listing.

R1 is substituted at C18 in 18-hyroxyretinoic acid.

Double bond is not always specific to this location.

Thus, a wide variety of analytical tools, especially mass spectrometry based methods, are now available for the investigation of retinoid biology. However, the optimal methodology depends on the specific hypothesis. Future development of these methods for retinoid biology is likely to be focused on reducing the amount of biological material required for LC/MS analyses, as well as reducing the detection limit of retinoid metabolites present in complex biological tissues. Mass spectrometry methods that perform in vivo sampling from live Xenopus embryos have been shown to yield highly sensitive, label-free protein identification from as little as a single blastomere (Lombard-Banek, Moody et al. 2016). Adapting this technology for retinoid detection will prove a highly useful advance to gain insight into the direct dynamics to retinoid metabolism in vivo.

8-Conclusions

RA signaling has broad function during embryogenesis in fate specification, patterning and organogenesis. As reviewed here, RA is especially critical during early development of craniofacial structures contributed by the neural crest and cranial placodes. Unlike other morphogens, RA is characterized by its ability to self-regulate its levels, through degradation-dependent mechanisms of feedback inhibition. RA gradients are robust, and the intracellular concentration required by individual cells is established locally through degradation by Cyp26 enzymes. Cyp26 enzymes degrade different isomers of RA rapidly into polar metabolites, and their expression can be induced by all-trans RA. Recent advances in mass spectrometry and liquid chromatography have made it possible to detect and quantify endogenous RA in tissues precisely and future studies will be better informed with a clear knowledge of the exact levels of RA needed to orchestrate complex developmental pathways.

Embryonic developmental programs across species frequently utilize RA gradient landscapes created by apposed RA synthesis and degradation domains, creating two adjacent region capable of exhibiting vastly different gene expression profiles. Due to its interactions with several other signaling pathways, disruptions in RA signaling have direct and indirect consequences, often resulting in severe developmental malformations. The main indirect effect of RA is exerted through the suppression of FGF signaling, which is also critical for several key processes during embryogenesis. Therefore, it is critical to maintain a robust RA gradient during development to establish spatial boundaries. Due to its superb complexity, RA signaling remains a field of active research in developmental biology. Moving forward, it is essential to elucidate the mechanisms by which RA signaling uses dose-dependence and positional identity to execute specific changes in gene expression.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health to J-P S-J (R01-DE025806 and R01-DE025468).

Bibliography