Abstract

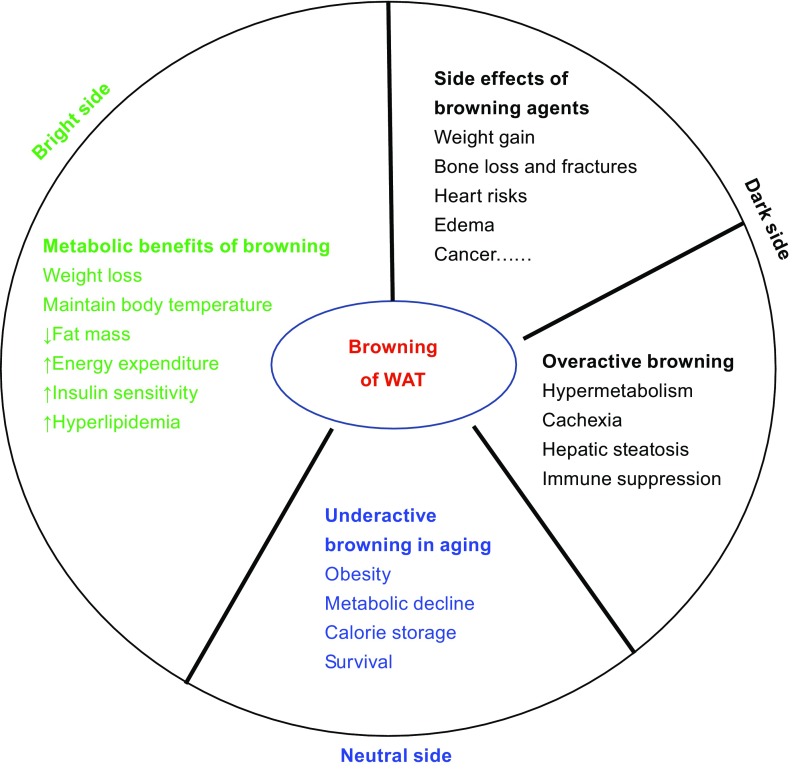

The induction of brown-like adipocyte development in white adipose tissue (WAT) confers numerous metabolic benefits by decreasing adiposity and increasing energy expenditure. Therefore, WAT browning has gained considerable attention for its potential to reverse obesity and its associated co-morbidities. However, this perspective has been tainted by recent studies identifying the detrimental effects of inducing WAT browning. This review aims to highlight the adverse outcomes of both overactive and underactive browning activity, the harmful side effects of browning agents, as well as the molecular brake-switch system that has been proposed to regulate this process. Developing novel strategies that both sustain the metabolic improvements of WAT browning and attenuate the related adverse side effects is therefore essential for unlocking the therapeutic potential of browning agents in the treatment of metabolic diseases.

KEYWORDS: adipocyte, browning, beige adipocyte, thermogenesis, obesity, diabetes

Introduction

Adipose tissue is sensitive to changes in nutrient supply and ambient temperature: an evolutionary development that has allowed animal species to adapt to food shortage and cold temperatures. In higher vertebrates, white adipose tissue (WAT) primarily stores energy in the form of triglycerides in unilocular white adipocytes, which can then be released as fatty acids when food is scarce (Zechner et al. 2012). In this way, endothermic animals are able to sustain their energy homeostasis long enough to survive through nutritional privation and maintain their core body temperature (Gesta et al. 2007; Zechner et al. 2012). On the other hand, brown adipose tissue (BAT) dissipates energy as heat in a process called non-shivering thermogenesis (Cannon and Nedergaard 2004). Brown adipocytes contain multilocular lipid droplets, densely packed mitochondria, and have a high expression of uncoupling protein 1 (UCP1). BAT is therefore highly metabolically active due to the uncoupling of electron transport from ATP production in the inner mitochondrial membrane, allowing for active substrate oxidation and a low rate of ATP production with heat generation instead.

BAT was previously known to be abundant only in hibernating mammals, interscapular regions of rodents, and supraclavicular regions of human newborns (SMITH and Hock 1963; Aherne and Hull 1966; Rothwell and Stock 1979). However, this has been displaced by the discovery of active BAT in the axillary, cervical, supraclavicular, and paravertebral regions of adult humans (Nedergaard et al. 2007; Cypess et al. 2009; van Marken Lichtenbelt et al. 2009; Virtanen et al. 2009). Together, brown and white adipose tissues orchestrate energy balance and thermal regulation in endothermic animals.

Beige adipocytes and browning

The accumulation of ‘brown-like’ adipocytes in WAT is referred to as ‘browning’ or ‘beiging’. These ‘brown-like’ adipocytes are referred to as beige or brite (brown-in-white) adipocytes, the activation of which upregulates Ucp1 and other genes involved in energy expenditure in WAT. Browning of WAT is an adaptive and reversible response to environmental stimuli, including cold exposure, pharmacological agents such as β3-adrenergic receptor agonists and thiazolidinediones (TZDs), as well as various peptides and hormones (Guerra et al. 1998; Himms-Hagen et al. 2000; Barbatelli et al. 2010; Fisher et al. 2012; Ohno et al. 2012; Rosenwald et al. 2013). Interestingly, characterization of BAT from adult humans has been shown to have a molecular profile more similar to beige fat than that of classical BAT (Wu et al. 2012; Frontini et al. 2013; Sidossis et al. 2015).

Beige adipocytes have multiple origins. They can originate from progenitors resident within WAT that are differentiated in response to browning stimuli—a process known as de novo differentiation (Wang et al. 2013). These beige adipocyte progenitors are smooth muscle-like pericytes that express platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF) receptor α but not Myf-5 (PDGFRα+; Myf5 −) (Seale et al. 2008; Lee et al. 2012; Sanchez-Gurmaches et al. 2012; Long et al. 2014). Alternatively, beige adipocytes can arise via transdifferentiation, a process that involves the direct conversion of existing white adipocytes into brown-like cells, and vice versa (Barbatelli et al. 2010; Rosenwald et al. 2013). In sum, beige adipocytes possess distinct phenotypic and functional characteristics from white and brown adipocytes that are underlain by their unique gene expression signature in response to environmental stimuli.

The regulation of browning

Transcriptional regulation

Cellular energy sensing and sympathetic tone are the driving forces that regulate the transcriptional networks controlling browning. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ (PPARγ) centers the browning transcriptional network. It has been proven to be necessary and sufficient for adipocyte differentiation and function (Farmer 2006). Chronic stimulation of primary adipocyte cultures with thiazolidinediones (TZD), a class of PPARγ ligands, induces activation of the PPARγ cofactor, PGC-1α (Wilson-Fritch et al. 2004), and stabilizes the BAT-specific cofactor, PR domain zinc finger protein 16 (PRDM16) (Ohno et al. 2012). In mice, Prdm16 stimulates the expression of several genes involved in thermogenesis in WAT, including Pgc-1α and Ucp1, even after stimulation by β3-adrenergic agonists (Seale et al. 2007; Seale et al. 2008). Vernochet et al. further demonstrated a direct role for PPARγ in the phenotypic conversion of WAT to BAT. Specifically, a mutation of the PPARγ ligand-binding domain suppressed TZD-mediated inhibition of white-adipocyte genes, including Resistin, Angiotensinogen and Chemerin, and induced brown-specific genes, including Ucp-1, in 3T3-L1 adipocytes (Vernochet et al. 2009). Such inhibition depends on the expression of C/EBPα and the corepressors, carboxy-terminal binding proteins 1 and 2 (CtBP1/2). On the molecular level, TZDs induce deacetylation of PPARγ by the NAD-dependent protein deacetylase sirtuin-1 (SirT1) to recruit browning cofactors such as PRDM16. This results in the selective activation of brown genes and the repression of white genes (Qiang et al. 2012).

Modulations of PPARγ through ligands, posttranslational modifications, isoform distinction (Li et al. 2016), and cofactor exchanges are all able to regulate browning. For example, EBF2 (Rajakumari et al. 2013) and TLE3 (Villanueva et al. 2011) were recently identified as brown and white adipocyte-specific regulators, respectively. Both of them function through PPARγ (Villanueva et al. 2013; Ferrannini et al. 2016). Another browning factor, IRF4, induces thermogenic activity in WAT by activating PRDM16 and PGC-1α, both of which are closely related to PPARγ (Kong et al. 2014). Taken together, PPARγ coupled with its upstream and downstream regulators comprises the browning regulatory axis.

Hormonal regulation

Cold exposure and other environmental stimuli elicit complex hormonal responses that facilitate adaptive thermogenesis and crosstalk between tissues. For example, lipid-derived hormones—such as prostaglandins, bone morphogenetic protein 4 (BMP-4), and fibroblast growth factor 21 (FGF21)—are produced in response to β3-adrenergic receptor activation to promote browning (Vegiopoulos et al. 2010; Fisher et al. 2012; Grefhorst et al. 2015). Furthermore, leptin is a nutrient-responsive adipokine that, together with insulin, promotes browning through POMC neurons (Dodd et al. 2015). The browning effect of leptin is counteracted by another representative adipokine: Adiponectin (encoded by Adipoq). Adipoq knock-out mice show increased thermogenic response (Qiao et al. 2014), in line with the decreased energy expenditure in its transgenic mice on ob/ob background (Kim et al. 2007). In addition, catecholamines are required for the immediate activation of brown and existing beige adipocytes, as well as for the differentiation of beige adipocytes from their precursors (Cannon and Nedergaard 2004). Adipose-tissue resident M2 macrophages were identified as a source of catecholamines involved in the regulation of lipolysis in response to acute cold exposure (Nguyen et al. 2011). Obesity induces a switch toward proinflammatory M1 macrophages (Lumeng et al. 2007) that might counteract the increased catecholamine production and therefore prevent browning. However, the production of catecholamines by adipose M2 macrophages was questioned in a recent study (Fischer et al. 2017), suggesting a revisit to the immune-regulation of browning. Moreover, secretory factors are suggested to mediate the crosstalk between muscle and fat in terms of exercise-induced brown remodeling in WAT (Moghri et al. 2013). Overall, it is agreed that energy sensing and metabolic demands are important regulators of the browning process. Various environmental stimuli cause the release of hormonal factors from adipose tissue and/or other metabolically active organs, all of which contribute to the maintenance of energy homeostasis.

Besides the mainstreams of transcriptional and hormonal regulations, various mechanisms have been identified to regulate browning that include cytoskeleton remodeling (McDonald et al. 2015), circadian rhythm (Gerhart-Hines et al. 2013), microRNAs (Kim et al. 2014), long non-coding RNAs (Alvarez-Dominguez et al. 2015), and the central nervous system (Liu et al. 2012; Hankir et al. 2016). Despite the continuously growing list of browning regulators, our opinion is that the challenge is not in identifying new browning factors but rather in understanding the precise mechanisms of browning in order to translate them safely and efficiently into clinical applications.

The metabolic benefits of browning

Browning in humans

Obesity confers an increased risk of developing insulin resistance, type 2 diabetes mellitus, and cardiovascular disease (Van Gaal et al. 2006; Guilherme et al. 2008). Browning of WAT has a number of positive implications for metabolic health by tilting the energy balance toward energy expenditure. Thus, stimulation of the activity of brown and beige adipocytes has gained considerable attention for its therapeutic potential in promoting overall metabolic health as recorded by reduced body weight, adiposity, insulin resistance, and hyperlipidemia. In humans, BAT mass, or indeed beige fat mass, and its functional activity are inversely related to body mass index, resting plasma glucose, and lipid levels (Saito et al. 2009). Conversely, increasing BAT activity by cold exposure, diet, or pharmacological agents is positively correlated with energy expenditure. For example, individuals subjected to 10-day cold exposure demonstrated enhanced glucose uptake in BAT, glucose oxidation, and insulin sensitivity (Chondronikola et al. 2014). In a study by Cypess et al., treatment with mirabegron, a β3-adrenergic receptor agonist, led to higher BAT metabolic activity and increased basal metabolic rate in healthy male subjects (Cypess et al. 2015). In addition, a 5–8 h exposure of overweight/obese men to a non-shivering cold environment (19.9 ± 0.8°C) activated BAT and increased the expression of lipid handling genes (Chondronikola et al. 2016). These studies suggest a role of beige fat in lipid metabolism, thermogenesis, and energy dissipation. However, it is too early to conclude the therapeutic consequences of inducing browning in humans for the prevention and management of metabolic diseases that include obesity, diabetes, and cardiovascular disease.

Genetic models of browning

Studies in genetic mouse models have further corroborated the metabolic benefits of browning. Adipose-specific overexpression of Ucp1 in agouti viable yellow (Avy) genetically obese mice resulted in reductions in total body weight and subcutaneous fat stores (Kopecky et al. 1995). These results were supported by another study where mice overexpressing Ucp1 in adipose tissue were resistant to diet-induced obesity (Stefl et al. 1998). This was attributed to ectopic expression of Ucp1 in white fat, thus increasing its thermogenic capacity. However, brown fat mass and its Ucp1 expression were drastically reduced in these mice, indicating that the resistance to obesity was largely due to the increased adaptive thermogenesis in WAT but not in BAT (Stefl et al. 1998). Mice overexpressing Prdm16 in fat tissue had marked increases of browning in WAT, specifically subcutaneous depots, resulting in protection from diet-induced obesity and glucose intolerance (Seale et al. 2011). Supportively, ablation of Prdm16 in fat impaired browning and led to obesity and insulin resistance (Cohen et al. 2014). Furthermore, overexpression of Cyclooxygenase 2 (Cox2), an enzyme involved in prostaglandin synthesis, also induced browning of WAT and consequently increased energy expenditure and reduced adiposity (Vegiopoulos et al. 2010).

Genes that have been highlighted in cancer, such as Foxc2, Pten, and Folliculin, also have been implicated in browning pathways. Overexpression of Foxc2 in HFD-fed mice resulted in reduced fat mass as well as protection from the associated insulin resistance and intramuscular accumulation of lipids (Cederberg et al. 2001; Kim et al. 2005). Overexpression of tumor suppressor Pten leads to increased energy expenditure, hyperactive BAT, and higher levels of Ucp1 in mice (Ortega-Molina et al. 2012). Folliculin (FLCN) is known for its role as a tumor suppressor and also has been implicated in metabolic reprogramming of adipose tissue (Wada et al. 2016). Ablation of Flcn in adipocytes results in increased energy expenditure and protection from diet-induced obesity. This is due to activation of Ucp1 and other BAT genes in both BAT and WAT, conferring an increased cold tolerance (Yan et al. 2016). Despite these metabolic benefits exhibited by the aforementioned mouse models with induced WAT browning, it remains to be determined whether they confer benefits in terms of eliminating risk to cancer.

The side effects of browning agents

While the metabolic benefits of browning in humans remain to be fully established, safety is a concern that must first be addressed regarding any method used to induce browning. Cold exposure is a classic and efficient way to induce browning, but its obvious discomfort, together with risks of hypothermia, makes it impractical for clinical use. Therefore, browning agents, either endogenous or exogenous, provide an attractive alternative for improving metabolic diseases. Here we discuss a few commonly used browning agents to draw attention to the safety concern of inducing WAT browning.

Thiazolidinediones (TZDs)

Thiazolidinediones (TZDs) are PPARγ agonists that were widely used as insulin sensitizers in the treatment of type 2 diabetes. In addition to their insulin sensitizing function, TZDs are well known to induce thermogenic gene expression in both white and brown adipocytes (Sell et al. 2004; Rong et al. 2007; Petrovic et al. 2010; Qiang et al. 2012). Although TZDs have been proven to be effective in the treatment of type 2 diabetes, their use has been limited by the incidence of adverse side effects, some of which include heart failure, edema, weight gain, and bone loss (Shah and Mudaliar 2010; Abbas et al. 2012; Soccio et al. 2014). In this regard, the first clinically available TZD, troglitazone, was withdrawn in 2000, three years after its approval by FDA, due to serious hepatotoxicity (Knowler et al. 2005). Similarly, rosiglitazone was banned in various countries in 2010 due to the increased incidence of heart attack and stroke. Nevertheless, the IRIS (Insulin Resistance Intervention after Stroke) clinical study recently reported a positive outcome in the use of pioglitazone for the treatment of heart disease associated with insulin resistance (Kernan et al. 2016). Non-diabetic patients with insulin resistance along with a recent history of ischemic stroke or transient ischemic attack (TIA) were treated with either pioglitazone or placebo. Pioglitazone was effective in reducing the risk of diabetes by 52% in addition to decreasing the risk of stroke or myocardial infarction by 24%. Despite these promising results, the adverse side effects of TZDs, such as bone loss, weight gain, and edema, were confirmed by this study. This highlights the need to further investigate the mechanisms of TZD action in order to harness the full therapeutic potential of these drugs for insulin sensitization and browning activation.

FGF21

Fibroblast growth factor 21 (FGF21) emerges as an insulin-mimetic hormone that regulates systemic energy balance and has beneficial effects on body weight, insulin sensitivity, dyslipidemia, and pancreatic β-cell growth (Kharitonenkov et al. 2005; Wente et al. 2006; Kharitonenkov et al. 2007; Coskun et al. 2008; Gaich et al. 2013). Interestingly, FGF21-treated mice show a marked increase in the expression of the key thermogenic genes Ucp1 and Dio2 in inguinal WAT (iWAT), whereas Fgf21-deficient mice show an impaired response to cold stress due to diminished thermogenic activity (Fisher et al. 2012). The browning capacity of FGF21 is mediated through stabilization of Pgc-1α (Chau et al. 2010; Fisher et al. 2012) or a positive-feedback on PPARγ activation (Dutchak et al. 2012).

One significant limitation to the use of FGF21 as a browning agent is the occurrence of severe bone loss. Wei et al. demonstrated that genetic Fgf21 gain-of-function, as well as pharmacological FGF21 treatment, in diet-induced obese mice reduced the number and area of osteoblasts and osteoclasts while increasing that of bone marrow adipocytes (Wei et al. 2012). In addition, chronic exposure to FGF21 has been linked to growth retardation in mice based on the development of growth hormone (GH) resistance in Fgf21-transgenic mice (Inagaki et al. 2008). Overexpression of Fgf21 has also been shown to cause infertility in female but not in male mice (Inagaki et al. 2007). Moreover, FGF21 reduces physical activity and promotes torpor in Fgf21 transgenic mice: a favorable adaptive response to starvation, but an undesirable outcome in the context of obesity (Inagaki et al. 2007). Hence, despite the beneficial effects of FGF21 in terms of improving insulin resistance and inducing browning, its severe side effects will have to be overcome for long-term clinical administration.

β3-Adrenergic receptor agonists

β3-adrenergic receptors (β3-AR) mediate thermogenesis in BAT and lipolysis in WAT; thus, activating these receptors with selective pharmacological agonists is an attractive strategy for stimulating the browning of WAT. A number of β3-AR agonists have been developed as anti-obesity agents. However, their harmful side effects have called into question whether the long-term stimulation of β3-ARs is safe and beneficial. Himms-Hagen et al. demonstrated that chronic treatment with a β3-AR agonist, CL 316,243, led to the appearance of multilocular brown adipocytes in WAT, promoted thermogenesis, and delayed the development of obesity in rats fed a high-fat diet (Himms-Hagen et al. 1994). However, its browning effects in humans are subtle with chronic administration (Weyer et al. 1998; Arch 2002). Another agonist, Mirabegron, a prescribed drug for treating overactive bladder, has been shown to activate BAT in young, lean, and healthy male humans at a dose of 200 mg/kg/day, but it also causes tachycardia (Cypess et al. 2015). A lower dose appeared safe, as reported by the BEAT-HF trial (Beta 3 Agonists Treatment in Heart Failure), after eliminating the intolerance to adverse events seen at the higher dose (Bundgaard et al. 2016). Therefore, more specific β3-AR agonists are desired for the treatment of obesity and diabetes, but their chronic effects must be closely monitored.

Thyroid hormone

Thyroid hormones (THs) T4 (thyroxine) and T3 (triiodothyronine) are key regulators of metabolism and energy homeostasis, and have been shown to induce WAT browning (Mullur et al. 2014). Low doses of the T3 metabolite, triiodothyracetic acid (TRIAC), induced ectopic expression of UCP1 in rat abdominal WAT (Medina-Gomez et al. 2008). Consistently, chronic administration of GC-1, a thyroid hormone receptor β-specific agonist, to obese mice markedly increased browning of subcutaneous WAT with a significant increase in core body temperature and whole body energy expenditure (Lin et al. 2015). Similar safety concerns for the use of β3-AR agonists have been raised for THs in terms of heart risks, hyperthermia, and weight loss (Moolman 2002; Mullur et al. 2014). THs have also been linked to an increased risk of fractures in postmenopausal women with lower serum thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) levels (Bauer et al. 2001), which directly affects bone turnover (Murphy and Williams 2004). This further emphasizes the need for browning agents to be carefully designed and controlled in order to ensure its safe metabolic benefits.

BMP7

Bone morphogenetic proteins-7 (BMP-7) is a member of the superfamily of transforming growth factor-β. It has been shown to singularly promote the differentiation of mesenchymal progenitor C3H10T1/2 cells to a brown adipocyte lineage (Tseng et al. 2008). Treatment of C57Bl6/J mice with BMP7 resulted in the extensive browning of WAT, as evidenced by increased expression of the BAT marker Ucp1 and the appearance of brown adipocyte clusters (Boon et al. 2013). Most notably, BMP7 treatment of diet-induced obese mice at subthermoneutrality also led to an improved metabolic profile in these mice as demonstrated by reduced fat mass, lower plasma glucose, and hepatic triglycerides (Boon et al. 2013). These results are promising in terms of a potential therapeutic approach for the treatment of obesity. However, it should be noted that BMP7 is approved by the FDA only for clinical practice in long bone trauma, spinal fusion, and oral and maxillofacial applications due to concerns of cancer and immunosuppression (Buijs et al. 2007; Boon et al. 2011; Carreira et al. 2014).

VEGF-A

VEGF-A is the master angiogenic factor and has been demonstrated to regulate the expansion and homeostasis of fat tissue (Sun et al. 2012; Elias et al. 2012; Lu et al. 2012; Sung et al. 2013). Using an inducible adipocyte-specific VEGF-A overexpression model, Sun et al. demonstrated that the local up-regulation of VEGF-A in adipocytes improved vascularization and led to the browning of WAT, with massive up-regulation of UCP1 and PGC-1α (Sun et al. 2012). This was accompanied by an increase in energy expenditure and resistance to high fat diet-mediated metabolic dysfunction (Sun et al. 2012). On the contrary, loss of VEGF-A in adipose tissue elicits browning of WAT (Lu et al. 2012). However, the consequences of the proangiogenic activity of VEGF-A may not always be beneficial. During adipose tissue expansion, VEGF-A evidently serves a protective role for the metabolically challenged adipose tissue by facilitating browning. In contrast, under conditions of preexisting adipose tissue dysfunction, the stimulation of angiogenesis and fat pad expansion would likely have the opposite—and therefore detrimental effect. For instance, anti-VEGF-A therapies have been applied to treat cancer and eye diseases (Ferrara and Adamis 2016). Thus, the nature of its proangiogenic properties and the related tumorigenic potential impedes the utilization of VEGF-A as a therapeutic browning agent in obesity and diabetes treatment.

Browning and hypermetabolism

Cachexia

Cachexia is a metabolic wasting syndrome characterized by severe weight loss, systemic inflammation, and atrophy of WAT and skeletal muscle. It is most commonly observed in cancer patients but has also been associated with burn injuries, infectious diseases (HIV, Tuberculosis), and chronic diseases (congestive heart failure, chronic kidney diseases, chronic obstructive lung disease) (Argilés et al. 2014). Cachexia contributes to the poor prognostic outcomes for these patients and specifically contributes to 20% of cancer-related deaths (Fearon et al. 2013; Argilés et al. 2014). Worse still is that an increase in calorie intake does not improve the cachectic state in patients (Pedroso et al. 2012).

Browning of WAT has primarily been discussed in light of its metabolic benefits: namely, increased energy expenditure, improved insulin sensitivity, and weight loss. However, recent studies have identified browning of WAT as a potential contributor to the development and progression of hypermetabolism in cachexia (Petruzzelli et al. 2014; Kir et al. 2014; Randall et al. 2015; Kir et al. 2016). In the K5-SOS mouse model of skin tumors that exhibits a rapid development of cachexia, energy expenditure was elevated while the respiratory exchange ratios (RER) were reduced, suggesting that lipids were used as the primary energy source in these cachectic mice. This explains the observed increase in catabolism of fatty acids in order to meet the high energy demand in cachexia (SMITH and Hock 1963). On the other hand, attenuation of lipolysis via genetic ablation of adipose triglyceride lipase (ATGL) not only preserves WAT but also prevents muscle wasting (Das et al. 2011). Therefore, browning of WAT in pathologic conditions, such as cancer and burn injury, adds fuel to an already highly catabolic state, leading to a number of deleterious consequences.

Cachexia factors and browning

Interleukin-6

Cachexia has also been described as a highly inflammatory state. There is evidence to suggest that cytokines and potentially other tumor-secreted factors may be responsible for inducing the hypermetabolic state and the consequent reduction in body weight and fat mass (Fearon et al. 2012). Recently, IL-6 has been shown to induce and sustain WAT browning in cachexia. Mice injected with IL-6 proficient C26 carcinoma cells rapidly lost body weight and became cachectic (Petruzzelli et al. 2014). Conversely, blocking IL-6 with a neutralizing monoclonal antibody or with sulindac, a nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID), reduces the severity of cachexia and suppresses the browning capacity of subcutaneous WAT (Petruzzelli et al. 2014).

PTH and PTHrP

Parathyroid-hormone (PTH) and Parathyroid-hormone-related protein (PTHrP) have been implicated in the browning of WAT in cachexia. PTHrP was originally recognized for its beneficial effects on skin, cartilage, placenta, and bone development (Maioli et al. 2002; Guntur et al. 2015). However, its function has recently been associated with hypermetabolic conditions and subsequent detrimental outcomes. Using Lewis lung carcinoma (LLC) cells as a model of cancer cachexia, tumor-derived PTHrP was shown to contribute to wasting by inducing the expression of thermogenic genes, including Ucp1, Dio2, and Pgc-1α (Kir et al. 2014). Treatment of the tumor-bearing mice with a PTHrP-neutralizing antibody inhibited adipose tissue browning and prevented loss of muscle mass and strength. In addition, parathyroid hormone (PTH) was shown to stimulate a thermogenic gene program in 5/6 nephrectomized mice (a model of chronic kidney disease) that suffer from cachexia (Kir et al. 2016). Consequently, fat-selective knockout of its signaling receptor, PthR, blocked adipose tissue browning and wasting, preserved muscle mass, and improved strength. In fact, these PthR knockout mice were resistant to tumor-induced cachexia (Kir et al. 2016).

Burn injury

Burn trauma causes hypermetabolism due to marked increases in catecholamines, which have been reported years after the initial injury (Kulp et al. 2010). This sustained increase in catecholamines leads to chronic activation of the β-adrenergic signaling pathway, which in turn initiates browning of WAT and the cascade of events leading to the hypermetabolic response (Sidossis et al. 2015; Patsouris et al. 2015). Most notably, it was recently shown that palmitate, an abundant free fatty acid found in the sera of burn patients, could regulate macrophage polarization (Xiu et al. 2015; Xiu et al. 2016). This interaction may suggest a detrimental feed-forward loop, where browning-induced lipolysis causes free fatty acid efflux, which in turn sustains the browning response during the hypermetabolic state. Further investigation is needed to clarify the function of browning in burn injury, whether it is beneficial to the recovery or contributes to the complications of burn injury. Additionally, a prolonged hypermetabolic state can result in hepatic steatosis and immune suppression (Jeschke 2009; Jeschke et al. 2014). In this regard, the long-term benefits of browning might be canceled out.

The role of browning in aging

Aging is arguably a major risk factor for metabolic syndrome (Tchkonia et al. 2010) and is accompanied by a loss of active BAT and beige adipocytes in WAT (Cypess et al. 2009; Saito et al. 2009; Rogers et al. 2012). In theory, this loss of browning capacity leads to the reduction in energy expenditure and the expansion of adiposity (Yoneshiro et al. 2011; Rogers et al. 2012), and thus contributes to the progressive metabolic decline associated with aging (Barzilai et al. 2012). The decrease of browning is likely caused by changes in gonadal hormones, desensitization to β-adrenergic signaling (Nedergaard and Cannon 2010) or other factors. Recently, Foxa3 has been identified as a novel transcriptional regulator that inhibits browning during aging (Ma et al. 2014). Although the loss of Foxa3 resulted in a lean, energy inefficient and more insulin sensitive phenotype in mice older than one year old (Ma et al. 2014), it has been suggested that Foxa3 is a “hoarder” gene to facilitate lipid storage in aged animals (Ma et al. 2015). Indeed, energy preservation is probably more important for survival during food deprivation, which is apparently a challenge for aged animals when their predatory ability declines. Therefore, the metabolic benefits of browning may be unveiled predominately under the conditions of nutrient excess.

The brake-switch system of browning

In recently years, significant progress has been made in identifying stimuli and signaling pathways that can induce browning of WAT and trigger adaptive thermogenesis. These advancements in knowledge have garnered great support in exploiting adipose tissue plasticity together with browning agents as therapeutic tools for obesity, albeit with side effects as discussed above. The revelation of the two sides of the coin regarding the browning of WAT—namely, that it mitigates the metabolic consequences of obesity but propagates a hypermetabolic state in other pathologic conditions—suggests that browning “wastes energy” and thus is not a favorable physiological state. Therefore, we hypothesized that the body needs to tightly regulate this browning process via a “brake-switch” system to prevent the negative outcomes of both hyper- and hypo-activation of browning activity (Ferrannini et al. 2016).

This “brake-switch” hypothesis is supported by the recent identification of HOXC10, a homeobox domain-containing transcription factor, as a negative regulator of browning of WAT (Ferrannini et al. 2016; Lim et al. 2016). It is enriched in subcutaneous fat, and the ectopic overexpression of HOXC10 suppressed brown fat genes and induced white adipocyte-specific genes with a minimal effect on the pan-adipocyte markers (Ferrannini et al. 2016; Ng et al. 2017). The HOXC10 browning-inhibitory effect is partially mediated by suppressing Prmd16 gene expression (Ng et al. 2017). Another molecular brake for browning is ZFP423 (Shao et al. 2016), which is a C2H2 zinc-finger protein that had previously been identified as a transcriptional regulator of preadipocyte determination (Gupta et al. 2010). Ablation of Zfp423 in white adipocytes led to the accumulation of beige adipocytes in WAT in adult mice, while its gain-of-function converted brown adipocytes into a more white-like phenotype (Shao et al. 2016). Taken together, HOXC10 and ZFP423 represent the native “brake” system in white adipocytes to release the browning activity only under appropriate conditions. This switch is likely dysregulated in the hypermetabolic state, as seen in cachexia, or the hypometabolic state, as seen in aging.

Conclusion

The browning of WAT has become an increasingly favorable strategy for ameliorating the effects of obesity and subsequent metabolic dysfunction. However, it is energetically inefficient and thus is physiologically unfavorable. Furthermore, recent evidence has implicated browning in the development of cachexia, lipotoxicity, and other detrimental outcomes under acute and chronic hypermetabolic conditions (as summarized in Fig. 1). The increasing awareness of the dark side of browning emphasizes the need to further investigate factors and mechanisms that regulate the activation and deactivation of browning. In this regard, the brake-switch system of browning may be critical for maintaining the proper function of BAT and WAT. Further investigation should be warranted to efficiently induce browning in a tissue-specific and tightly controlled manner in order to minimize the occurrence of negative effects and to maximize the therapeutic potential of browning agents in the treatment of metabolic disorders.

Figure 1.

A summary of the metabolic benefits and adverse outcomes associated with the induction of browning

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We would like to thank members of Qiang laboratory for insightful discussion. This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grants R00DK97455 to L. Q., Pilot and Feasibility funding from the Diabetes Research Center to L.Q. (P30 DK063608), training grant to K. A. T (T32 DK007647-27).

ABBREVIATIONS

ATGL, adipose triglyceride lipase; ATP, adenosine triphosphate; BAT, brown adipose tissue; β3-AR, beta 3-adrenergic receptor; BMP4, bone morphogenetic protein 4; BMP7, bone morphogenetic protein 7; C/EBPα, CCAAT/enhancer binding protein alpha; CL 316,243, beta 3-adrenergic receptor agonist; COX2, cyclooxygenase 2; CtBP1/2, carboxy-terminal binding proteins 1 and 2; DIO2, deiodinase, iodothyronine type 2; EBF2, early B-cell factor 2; FDA, food and drug administration; FGF21, fibroblast growth factor 21; FLCN, folliculin; FOXA3, forkhead box A3; FOXC2, forkhead box C2; GC-1, thyroid hormone receptor beta-specific agonist; GH, growth hormone; HFD, high fat diet; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; HOXC10, homeobox C10; IL-6, interleukin-6; IRF4, interferon regulatory factor 4; MYF-5, myogenic factor 5; NAD, nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide; NSAID, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug; PDGFRα, platelet derived growth factor receptor alpha; PGC-1α, PPAR gamma coactivator 1 alpha; PPARγ, peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma; PRDM16, PR-domain zinc finger protein 16; PTEN, phosphatase and tensin homolog; PTH, parathyroid-hormone; PTHrP, parathyroid-hormone-related protein; RER, respiratory exchange ratio; SirT1, sirtuin-1; T3, triiodothyronine; T4, thyroxyne; TIA, transient ischemic attack; TLE3, transducin like enhancer of split 3; TRIAC, triiodothyracetic acid; TSH, thyroid-stimulating hormone; TZD, thiazolidinedione; UCP1, uncoupling protein 1; VEGF-A, vascular endothelial growth factor A; WAT, white adipose tissue; ZFP423, zinc finger protein 423.

COMPLIANCE WITH ETHICS GUIDELINES

Kirstin A. Tamucci, Maria Namwanje, Lihong Fan, Li Qiang declare that they have no conflict of interest. This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by the any of the authors.

Footnotes

Kirstin A. Tamucci and Maria Namwanje have contributed equally to this study.

REFERENCES

- Abbas A, Blandon J, Rude J, et al. PPAR-γ agonist in treatment of diabetes: cardiovascular safety considerations. Cardiovasc Hematol Agents Med Chem. 2012;10:124–134. doi: 10.2174/187152512800388948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aherne W, Hull D. Brown adipose tissue and heat production in the newborn infant. J Pathol Bacteriol. 1966;91:223–234. doi: 10.1002/path.1700910126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alvarez-Dominguez JR, Bai Z, Xu D, et al. De novo reconstruction of adipose tissue transcriptomes reveals long non-coding RNA regulators of brown adipocyte development. Cell Metab. 2015;21:764–776. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2015.04.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arch JRS. beta(3)-Adrenoceptor agonists: potential, pitfalls and progress. Eur J Pharmacol. 2002;440:99–107. doi: 10.1016/S0014-2999(02)01421-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Argilés JM, Busquets S, Stemmler B, López-Soriano FJ. Cancer cachexia: understanding the molecular basis. Nat Rev Cancer. 2014;14:754–762. doi: 10.1038/nrc3829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barbatelli G, Murano I, Madsen L, et al. The emergence of cold-induced brown adipocytes in mouse white fat depots is determined predominantly by white to brown adipocyte transdifferentiation. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2010;298:E1244–E1253. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00600.2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barzilai N, Huffman DM, Muzumdar RH, Bartke A. The critical role of metabolic pathways in aging. Diabetes. 2012;61:1315–1322. doi: 10.2337/db11-1300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauer DC, Ettinger B, Nevitt MC, et al. Risk for fracture in women with low serum levels of thyroid-stimulating hormone. Ann Intern Med. 2001;134:561–568. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-134-7-200104030-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boon MR, van der Horst G, van der Pluijm G, et al. Bone morphogenetic protein 7: a broad-spectrum growth factor with multiple target therapeutic potency. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2011;22:221–229. doi: 10.1016/j.cytogfr.2011.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boon MR, van den Berg SAA, Wang Y, et al. BMP7 activates brown adipose tissue and reduces diet-induced obesity only at subthermoneutrality. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e74083. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0074083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buijs JT, Henriquez NV, van Overveld PGM, et al. TGF-beta and BMP7 interactions in tumour progression and bone metastasis. Clin Exp Metastasis. 2007;24:609–617. doi: 10.1007/s10585-007-9118-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bundgaard H, Axelsson A, Hartvig Thomsen J, et al. The-first-in-man randomized trial of a beta3 adrenoceptor agonist in chronic heart failure: the BEAT-HF trial. Eur J Heart Fail. 2016 doi: 10.1002/ejhf.714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cannon B, Nedergaard J. Brown adipose tissue: function and physiological significance. Physiol Rev. 2004;84:277–359. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00015.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carreira AC, Lojudice FH, Halcsik E, et al. Bone morphogenetic proteins: facts, challenges, and future perspectives. J Dent Res. 2014;93:335–345. doi: 10.1177/0022034513518561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cederberg A, Gronning LM, Ahren B, et al. FOXC2 is a winged helix gene that counteracts obesity, hypertriglyceridemia, and diet-induced insulin resistance. Cell. 2001;106:563–573. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(01)00474-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chau MDL, Gao J, Yang Q, et al. Fibroblast growth factor 21 regulates energy metabolism by activating the AMPK-SIRT1-PGC-1alpha pathway. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:12553–12558. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1006962107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chondronikola M, Volpi E, Børsheim E, et al. Brown adipose tissue improves whole-body glucose homeostasis and insulin sensitivity in humans. Diabetes. 2014;63:4089–4099. doi: 10.2337/db14-0746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chondronikola M, Volpi E, Børsheim E, et al. Brown adipose tissue activation is linked to distinct systemic effects on lipid metabolism in humans. Cell Metab. 2016;23:1200–1206. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2016.04.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen P, Levy JD, Zhang Y, et al. Ablation of PRDM16 and beige adipose causes metabolic dysfunction and a subcutaneous to visceral fat switch. Cell. 2014;156:304–316. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.12.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coskun T, Bina HA, Schneider MA, et al. Fibroblast growth factor 21 corrects obesity in mice. Endocrinology. 2008;149:6018–6027. doi: 10.1210/en.2008-0816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cypess AM, Lehman S, Williams G, et al. Identification and importance of brown adipose tissue in adult humans. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:1509–1517. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0810780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cypess AM, Weiner LS, Roberts-Toler C, et al. Activation of human brown adipose tissue by a β3-adrenergic receptor agonist. Cell Metab. 2015;21:33–38. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2014.12.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Das SK, Eder S, Schauer S, et al. Adipose triglyceride lipase contributes to cancer-associated cachexia. Science. 2011;333:233–238. doi: 10.1126/science.1198973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dodd GT, Decherf S, Loh K, et al. Leptin and insulin act on POMC neurons to promote the browning of white fat. Cell. 2015;160:88–104. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.12.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dutchak PA, Katafuchi T, Bookout AL, et al. Fibroblast growth factor-21 regulates PPARγ activity and the antidiabetic actions of thiazolidinediones. Cell. 2012;148:556–567. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.11.062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elias I, Franckhauser S, Ferré T, et al. Adipose tissue overexpression of vascular endothelial growth factor protects against diet-induced obesity and insulin resistance. Diabetes. 2012;61:1801–1813. doi: 10.2337/db11-0832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farmer SR. Transcriptional control of adipocyte formation. Cell Metab. 2006;4:263–273. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2006.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fearon KCH, Glass DJ, Guttridge DC. Cancer cachexia: mediators, signaling, and metabolic pathways. Cell Metab. 2012;16:153–166. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2012.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fearon K, Arends J, Baracos V. Understanding the mechanisms and treatment options in cancer cachexia. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2013;10:90–99. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2012.209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrannini G, Namwanje M, Fang B, et al. Genetic backgrounds determine brown remodeling of white fat in rodents. Mol Metab. 2016;5:948–958. doi: 10.1016/j.molmet.2016.08.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrara N, Adamis AP. Ten years of anti-vascular endothelial growth factor therapy. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2016;15:385–403. doi: 10.1038/nrd.2015.17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer K, Ruiz HH, Jhun K, et al. Alternatively activated macrophages do not synthesize catecholamines or contribute to adipose tissue adaptive thermogenesis. Nat Med. 2017;23:623–630. doi: 10.1038/nm.4316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher FM, Kleiner S, Douris N, et al. FGF21 regulates PGC-1{alpha} and browning of white adipose tissues in adaptive thermogenesis. Genes & Development. 2012;26:271–281. doi: 10.1101/gad.177857.111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frontini A, Vitali A, Perugini J, et al. White-to-brown transdifferentiation of omental adipocytes in patients affected by pheochromocytoma. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2013;1831:950–959. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2013.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaich G, Chien JY, Fu H, et al. The effects of LY2405319, an FGF21 analog, in obese human subjects with type 2 diabetes. Cell Metab. 2013;18:333–340. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2013.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerhart-Hines Z, Feng D, Emmett MJ, et al. The nuclear receptor Rev-erbα controls circadian thermogenic plasticity. Nature. 2013;503:410–413. doi: 10.1038/nature12642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gesta S, Tseng YH, Kahn CR. Developmental origin of fat: tracking obesity to its source. Cell. 2007;131:242–256. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grefhorst A, van den Beukel JC, van Houten ELA, et al. Estrogens increase expression of bone morphogenetic protein 8b in brown adipose tissue of mice. Biol Sex Differ. 2015;6:7. doi: 10.1186/s13293-015-0025-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guerra C, Koza RA, Yamashita H, et al. Emergence of brown adipocytes in white fat in mice is under genetic control. Effects on body weight and adiposity. J Clin Invest. 1998;102:412–420. doi: 10.1172/JCI3155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guilherme A, Virbasius JV, Puri V, Czech MP. Adipocyte dysfunctions linking obesity to insulin resistance and type 2 diabetes. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2008;9:367–377. doi: 10.1038/nrm2391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guntur AR, Doucette CR, Rosen CJ. PTHrp comes full circle in cancer biology. Bonekey Rep. 2015;4:621. doi: 10.1038/bonekey.2014.116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta RK, Arany Z, Seale P, et al. Transcriptional control of preadipocyte determination by Zfp423. Nature. 2010;464:619–623. doi: 10.1038/nature08816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hankir MK, Cowley MA, Fenske WK. A BAT-centric approach to the treatment of diabetes: turn on the brain. Cell Metab. 2016;24:31–40. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2016.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Himms-Hagen J, Cui J, Danforth EJ, et al. Effect of CL-316,243, a thermogenic beta 3-agonist, on energy balance and brown and white adipose tissues in rats. Am J Physiol. 1994;266:R1371–R1382. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1994.266.4.R1371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Himms-Hagen J, Melnyk A, Zingaretti MC, et al. Multilocular fat cells in WAT of CL-316243-treated rats derive directly from white adipocytes. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2000;279:C670–C681. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.2000.279.3.C670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inagaki T, Dutchak P, Zhao G, et al. Endocrine regulation of the fasting response by PPARalpha-mediated induction of fibroblast growth factor 21. Cell Metab. 2007;5:415–425. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2007.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inagaki T, Lin VY, Goetz R, et al. Inhibition of growth hormone signaling by the fasting-induced hormone FGF21. Cell Metab. 2008;8:77–83. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2008.05.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeschke MG. The hepatic response to thermal injury: is the liver important for postburn outcomes? Mol Med. 2009;15:337–351. doi: 10.2119/molmed.2009.00005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeschke MG, Gauglitz GG, Finnerty CC, et al. Survivors versus nonsurvivors postburn: differences in inflammatory and hypermetabolic trajectories. Ann Surg. 2014;259:814–823. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e31828dfbf1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kernan WN, Viscoli CM, Furie KL, et al. Pioglitazone after ischemic stroke or transient ischemic attack. N Engl J Med. 2016;374:1321–1331. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1506930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kharitonenkov A, Shiyanova TL, Koester A, et al. FGF-21 as a novel metabolic regulator. J Clin Invest. 2005;115:1627–1635. doi: 10.1172/JCI23606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kharitonenkov A, Wroblewski VJ, Koester A, et al. The metabolic state of diabetic monkeys is regulated by fibroblast growth factor-21. Endocrinology. 2007;148:774–781. doi: 10.1210/en.2006-1168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim JK, Kim H-J, Park S-Y, et al. Adipocyte-specific overexpression of FOXC2 prevents diet-induced increases in intramuscular fatty acyl CoA and insulin resistance. Diabetes. 2005;54:1657–1663. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.54.6.1657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim J-Y, van de Wall E, Laplante M, et al. Obesity-associated improvements in metabolic profile through expansion of adipose tissue. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:2621–2637. doi: 10.1172/JCI31021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim H-J, Cho H, Alexander R, et al. MicroRNAs are required for the feature maintenance and differentiation of brown adipocytes. Diabetes. 2014;63:4045–4056. doi: 10.2337/db14-0466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kir S, White JP, Kleiner S, et al. Tumour-derived PTH-related protein triggers adipose tissue browning and cancer cachexia. Nature. 2014;513:100–104. doi: 10.1038/nature13528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kir S, Komaba H, Garcia AP, et al. PTH/PTHrP receptor mediates cachexia in models of kidney failure and cancer. Cell Metab. 2016;23:315–323. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2015.11.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knowler WC, Hamman RF, Edelstein SL, et al. Prevention of type 2 diabetes with troglitazone in the Diabetes Prevention Program. Diabetes. 2005;54:1150–1156. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.54.4.1150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kong X, Banks A, Liu T, et al. IRF4 is a key thermogenic transcriptional partner of PGC-1α. Cell. 2014;158:69–83. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.04.049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kopecky J, Clarke G, Enerback S, et al. Expression of the mitochondrial uncoupling protein gene from the aP2 gene promoter prevents genetic obesity. J Clin Invest. 1995;96:2914–2923. doi: 10.1172/JCI118363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kulp GA, Herndon DN, Lee JO, et al. Extent and magnitude of catecholamine surge in pediatric burned patients. Shock. 2010;33:369–374. doi: 10.1097/SHK.0b013e3181b92340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee Y-H, Petkova AP, Mottillo EP, Granneman JG. In vivo identification of bipotential adipocyte progenitors recruited by β3-adrenoceptor activation and high-fat feeding. Cell Metab. 2012;15:480–491. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2012.03.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li D, Zhang F, Zhang X, et al. Distinct functions of PPARγ isoforms in regulating adipocyte plasticity. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2016;481:132–138. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2016.10.152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim YC, Chia SY, Jin S, et al. Dynamic DNA methylation landscape defines brown and white cell specificity during adipogenesis. Mol Metab. 2016;5:1033–1041. doi: 10.1016/j.molmet.2016.08.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin JZ, Martagón AJ, Cimini SL, et al. Pharmacological activation of thyroid hormone receptors elicits a functional conversion of white to brown fat. Cell Rep. 2015;13:1528–1537. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2015.10.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu T, Kong D, Shah BP, et al. Fasting activation of AgRP neurons requires NMDA receptors and involves spinogenesis and increased excitatory tone. Neuron. 2012;73:511–522. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.11.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Long JZ, Svensson KJ, Tsai L, et al. A smooth muscle-like origin for beige adipocytes. Cell Metab. 2014;19:810–820. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2014.03.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu X, Ji Y, Zhang L, et al. Resistance to obesity by repression of VEGF gene expression through induction of brown-like adipocyte differentiation. Endocrinology. 2012;153:3123–3132. doi: 10.1210/en.2012-1151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lumeng CN, Bodzin JL, Saltiel AR. Obesity induces a phenotypic switch in adipose tissue macrophage polarization. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:175–184. doi: 10.1172/JCI29881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma X, Xu L, Gavrilova O, Mueller E. Role of forkhead box protein A3 in age-associated metabolic decline. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2014;111:14289–14294. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1407640111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma X, Xu L, Mueller E. Calorie hoarding and thrifting: Foxa3 finds a way. Adipocyte. 2015;4:325–328. doi: 10.1080/21623945.2015.1028700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maioli E, Fortino V, Torricelli C, et al. Effect of parathyroid hormone-related protein on fibroblast proliferation and collagen metabolism in human skin. Exp Dermatol. 2002;11:302–310. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0625.2002.110403.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonald ME, Li C, Bian H, et al. Myocardin-related transcription factor A regulates conversion of progenitors to beige adipocytes. Cell. 2015;160:105–118. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.12.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medina-Gomez G, Calvo RM, Obregon MJ. Thermogenic effect of triiodothyroacetic acid at low doses in rat adipose tissue without adverse side effects in the thyroid axis. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2008;294:E688–E697. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00417.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moghri J, Akbari Sari A, Yousefi M, et al. Is scores derived from the most internationally applied patient safety culture assessment tool correct? Iran J Public Health. 2013;42:1058–1066. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moolman JA. Thyroid hormone and the heart. Cardiovasc J S Afr. 2002;13:159–163. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mullur R, Liu Y-Y, Brent GA. Thyroid hormone regulation of metabolism. Physiol Rev. 2014;94:355–382. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00030.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy E, Williams GR. The thyroid and the skeleton. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 2004;61:285–298. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2265.2004.02053.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nedergaard J, Cannon B. The changed metabolic world with human brown adipose tissue: therapeutic visions. Cell Metab. 2010;11:268–272. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2010.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nedergaard J, Bengtsson T, Cannon B. Unexpected evidence for active brown adipose tissue in adult humans. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2007;293:E444–E452. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00691.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ng Y, Tan S-X, Chia SY, et al. HOXC10 suppresses browning of white adipose tissues. Exp Mol Med. 2017;49:e292. doi: 10.1038/emm.2016.144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen KD, Qiu Y, Cui X, et al. Alternatively activated macrophages produce catecholamines to sustain adaptive thermogenesis. Nature. 2011;480:104–108. doi: 10.1038/nature10653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohno H, Shinoda K, Spiegelman BM, Kajimura S. PPARγ agonists induce a white-to-brown fat conversion through stabilization of PRDM16 protein. Cell Metab. 2012;15:395–404. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2012.01.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ortega-Molina A, Efeyan A, Lopez-Guadamillas E, et al. Pten positively regulates brown adipose function, energy expenditure, and longevity. Cell Metab. 2012;15:382–394. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2012.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patsouris D, Qi P, Abdullahi A, et al. Burn induces browning of the subcutaneous white adipose tissue in mice and humans. Cell Rep. 2015;13:1538–1544. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2015.10.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pedroso FE, Spalding PB, Cheung MC. Inflammation, organomegaly, and muscle wasting despite hyperphagia in a mouse model of burn cachexia. J Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle. 2012;3(3):199–211. doi: 10.1007/s13539-012-0062-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petrovic N, Walden TB, Shabalina IG, et al. Chronic peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma (PPARgamma) activation of epididymally derived white adipocyte cultures reveals a population of thermogenically competent, UCP1-containing adipocytes molecularly distinct from classic brown adipocytes. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:7153–7164. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.053942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petruzzelli M, Schweiger M, Schreiber R, et al. A switch from white to brown fat increases energy expenditure in cancer-associated cachexia. Cell Metab. 2014;20:433–447. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2014.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qiang L, Wang L, Kon N, et al. Brown remodeling of white adipose tissue by SirT1-dependent deacetylation of Pparγ. Cell. 2012;150:620–632. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.06.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qiao L, Yoo HS, Bosco C, et al. Adiponectin reduces thermogenesis by inhibiting brown adipose tissue activation in mice. Diabetologia. 2014;57:1027–1036. doi: 10.1007/s00125-014-3180-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rajakumari S, Wu J, Ishibashi J, et al. EBF2 determines and maintains brown adipocyte identity. Cell Metab. 2013;17:562–574. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2013.01.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Randall SM, Fear MW, Wood FM, et al. Long-term musculoskeletal morbidity after adult burn injury: a population-based cohort study. BMJ Open. 2015;5:e009395. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-009395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers NH, Landa A, Park S, Smith RG. Aging leads to a programmed loss of brown adipocytes in murine subcutaneous white adipose tissue. Aging Cell. 2012;11:1074–1083. doi: 10.1111/acel.12010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rong JX, Qiu Y, Hansen MK, et al. Adipose mitochondrial biogenesis is suppressed in db/db and high-fat diet-fed mice and improved by rosiglitazone. Diabetes. 2007;56:1751–1760. doi: 10.2337/db06-1135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenwald M, Perdikari A, Rülicke T, Wolfrum C. Bi-directional interconversion of brite and white adipocytes. Nat Cell Biol. 2013;15:659–667. doi: 10.1038/ncb2740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothwell NJ, Stock MJ. A role for brown adipose tissue in diet-induced thermogenesis. Nature. 1979;281:31–35. doi: 10.1038/281031a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saito M, Okamatsu-Ogura Y, Matsushita M, et al. High incidence of metabolically active brown adipose tissue in healthy adult humans: effects of cold exposure and adiposity. Diabetes. 2009;58:1526–1531. doi: 10.2337/db09-0530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez-Gurmaches J, Hung C-M, Sparks CA, et al. PTEN loss in the Myf5 lineage redistributes body fat and reveals subsets of white adipocytes that arise from Myf5 precursors. Cell Metab. 2012;16:348–362. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2012.08.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seale P, Kajimura S, Yang W, et al. Transcriptional control of brown fat determination by PRDM16. Cell Metab. 2007;6:38–54. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2007.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seale P, Bjork B, Yang W, et al. PRDM16 controls a brown fat/skeletal muscle switch. Nature. 2008;454:961–967. doi: 10.1038/nature07182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seale P, Conroe HM, Estall J, et al. Prdm16 determines the thermogenic program of subcutaneous white adipose tissue in mice. J Clin Invest. 2011;121:96–105. doi: 10.1172/JCI44271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sell H, Berger JP, Samson P, et al. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma agonism increases the capacity for sympathetically mediated thermogenesis in lean and ob/ob mice. Endocrinology. 2004;145:3925–3934. doi: 10.1210/en.2004-0321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shah P, Mudaliar S. Pioglitazone: side effect and safety profile. Expert Opin Drug Saf. 2010;9:347–354. doi: 10.1517/14740331003623218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shao M, Ishibashi J, Kusminski CM, et al. Zfp423 maintains white adipocyte identity through suppression of the beige cell thermogenic gene program. Cell Metab. 2016;23:1167–1184. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2016.04.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sidossis LS, Porter C, Saraf MK, et al. Browning of subcutaneous white adipose tissue in humans after severe adrenergic stress. Cell Metab. 2015;22:219–227. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2015.06.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith RE, Hock RJ. Brown fat: thermogenic effector of arousal in hibernators. Science. 1963;140:199–200. doi: 10.1126/science.140.3563.199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soccio RE, Chen ER, Lazar MA. Thiazolidinediones and the promise of insulin sensitization in type 2 diabetes. Cell Metab. 2014;20:573–591. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2014.08.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stefl B, Janovská A, Hodný Z, et al. Brown fat is essential for cold-induced thermogenesis but not for obesity resistance in aP2-Ucp mice. Am J Physiol. 1998;274:E527–E533. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.1998.274.3.E527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun K, Wernstedt Asterholm I, Kusminski CM, et al. Dichotomous effects of VEGF-A on adipose tissue dysfunction. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109:5874–5879. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1200447109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sung H-K, Doh K-O, Son JE, et al. Adipose vascular endothelial growth factor regulates metabolic homeostasis through angiogenesis. Cell Metab. 2013;17:61–72. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2012.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tchkonia T, Morbeck DE, Von Zglinicki T, et al. Fat tissue, aging, and cellular senescence. Aging Cell. 2010;9:667–684. doi: 10.1111/j.1474-9726.2010.00608.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tseng YH, Kokkotou E, Schulz TJ, et al. New role of bone morphogenetic protein 7 in brown adipogenesis and energy expenditure. Nature. 2008;454:1000–1004. doi: 10.1038/nature07221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Gaal LF, Mertens IL, De Block CE. Mechanisms linking obesity with cardiovascular disease. Nature. 2006;444:875–880. doi: 10.1038/nature05487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Marken Lichtenbelt WD, Vanhommerig JW, Smulders NM, et al. Cold-activated brown adipose tissue in healthy men. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:1500–1508. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0808718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vegiopoulos A, Müller-Decker K, Strzoda D, et al. Cyclooxygenase-2 controls energy homeostasis in mice by de novo recruitment of brown adipocytes. Science. 2010;328:1158–1161. doi: 10.1126/science.1186034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vernochet C, Peres SB, Davis KE, et al. C/EBPalpha and the corepressors CtBP1 and CtBP2 regulate repression of select visceral white adipose genes during induction of the brown phenotype in white adipocytes by peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma agonists. Mol Cell Biol. 2009;29:4714–4728. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01899-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Villanueva CJ, Waki H, Godio C, et al. TLE3 is a dual-function transcriptional coregulator of adipogenesis. Cell Metab. 2011;13:413–427. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2011.02.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Villanueva CJ, Vergnes L, Wang J, et al. Adipose subtype-selective recruitment of TLE3 or Prdm16 by PPARγ specifies lipid storage versus thermogenic gene programs. Cell Metab. 2013;17:423–435. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2013.01.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Virtanen KA, Lidell ME, Orava J, et al. Functional brown adipose tissue in healthy adults. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:1518–1525. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0808949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wada S, Neinast M, Jang C, et al. The tumor suppressor FLCN mediates an alternate mTOR pathway to regulate browning of adipose tissue. Genes Dev. 2016;30:2551–2564. doi: 10.1101/gad.287953.116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang QA, Tao C, Gupta RK, Scherer PE. Tracking adipogenesis during white adipose tissue development, expansion and regeneration. Nat Med. 2013;19:1338–1344. doi: 10.1038/nm.3324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei W, Dutchak PA, Wang X, et al. Fibroblast growth factor 21 promotes bone loss by potentiating the effects of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109:3143–3148. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1200797109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wente W, Efanov AM, Brenner M, et al. Fibroblast growth factor-21 improves pancreatic beta-cell function and survival by activation of extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1/2 and Akt signaling pathways. Diabetes. 2006;55:2470–2478. doi: 10.2337/db05-1435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weyer C, Tataranni PA, Snitker S, et al. Increase in insulin action and fat oxidation after treatment with CL 316,243, a highly selective beta3-adrenoceptor agonist in humans. Diabetes. 1998;47:1555–1561. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.47.10.1555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson-Fritch L, Nicoloro S, Chouinard M, et al. Mitochondrial remodeling in adipose tissue associated with obesity and treatment with rosiglitazone. J Clin Invest. 2004;114:1281–1289. doi: 10.1172/JCI21752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu J, Boström P, Sparks LM, et al. Beige adipocytes are a distinct type of thermogenic fat cell in mouse and human. Cell. 2012;150:366–376. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.05.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiu F, Catapano M, Diao L, et al. Prolonged endoplasmic reticulum-stressed hepatocytes drive an alternative macrophage polarization. Shock. 2015;44:44–51. doi: 10.1097/SHK.0000000000000373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiu F, Diao L, Qi P, et al. Palmitate differentially regulates the polarization of differentiating and differentiated macrophages. Immunology. 2016;147:82–96. doi: 10.1111/imm.12543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan M, Audet-Walsh É, Manteghi S, et al. Chronic AMPK activation via loss of FLCN induces functional beige adipose tissue through PGC-1α/ERRα. Genes Dev. 2016;30:1034–1046. doi: 10.1101/gad.281410.116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoneshiro T, Aita S, Matsushita M, et al. Age-related decrease in cold-activated brown adipose tissue and accumulation of body fat in healthy humans. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2011;19:1755–1760. doi: 10.1038/oby.2011.125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zechner R, Zimmermann R, Eichmann TO, et al. FAT SIGNALS—lipases and lipolysis in lipid metabolism and signaling. Cell Metab. 2012;15:279–291. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2011.12.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]