Abstract

Gray mold, caused by the fungus Botrytis cinerea, is the most significant postharvest disease of kiwifruit. In the present study, iTRAQ with LC-ESI-MS/MS was used to identify the kiwifruit proteins associated with the response to B. cinerea. A total of 2,487 proteins in kiwifruit were identified. Among them, 292 represented differentially accumulated proteins (DAPs), with 196 DAPs having increased, and 96 DAPs having decreased in accumulation in B. cinerea-inoculated vs. water-inoculated, control kiwifruits. DAPs were associated with penetration site reorganization, cell wall degradation, MAPK cascades, ROS signaling, and PR proteins. In order to examine the corresponding transcriptional levels of the DAPs, RT-qPCR was conducted on a subset of 9 DAPs. In addition, virus-induced gene silencing was used to examine the role of myosin 10 in kiwifruit, a gene modulating host penetration resistance to fungal infection, in response to B. cinerea infection. The present study provides new insight on the understanding of the interaction between kiwifruit and B. cinerea.

Keywords: defense response, gray mold, proteomics, kiwifruit-B.cinerea interaction, postharvest decay

Introduction

Kiwifruit is subject to postharvest fungal decay, resulting in significant economic losses during storage and transport. Among postharvest diseases, gray mold, caused by the fungal pathogen Botrytis cinerea, is the most devastating (Park et al., 2015). Although chemical (Minas et al., 2010), physical (Chen et al., 2015), and biological (Kulakiotu et al., 2004) approaches have been developed to control gray mold of kiwifruit, a comprehensive understanding of the pathogenesis of B. cinerea on kiwifruit is lacking.

B. cinerea is a necrotrophic fungal pathogen in the Sclerotiniaceae. It has a wide host range and can infect more than 200 host plant species, being especially destructive on fruits and vegetables (Wiilliamson et al., 2007). B. cinerea secretes a large number of extracellular proteins that facilitate wound invasion and colonization, and thus contribute to virulence (González-Fernández et al., 2015; Liu et al., 2017). Several B. cinerea genes related to its growth and virulence have been characterized. Harren et al. (2012) reported that two Ca2+/calcineurin-dependent signaling pathway genes, BcCnA and BcRcn1, regulated fungal development and virulence in B. cinerea. More recently, a Rab/GTPase family gene, Bcsas1, was shown to impact the growth, development, and secretion of extracellular proteins in B. cinerea, in a manner that decreased virulence (Zhang et al., 2014).

Proteomics has emerged as a powerful tool for understanding the molecular mechanism of plant-pathogen interactions (Imam et al., 2017). Using proteomics, the response of B. cinerea to plant-based elicitors and hormones (Dieryckx et al., 2015; Liñeiro et al., 2016), and the in vitro secretome of B. cinerea related to pathogenesis (González-Fernández et al., 2015) have been characterized. In general, proteomic analyses of plant hosts in response to fungal pathogens have been widely reported in recent years. For instance, Zhang et al. (2017b) employed an iTRAQ-based proteomic analysis of cotton to Rhizoctonia solani infection and reported that ROS homeostasis, epigenetic regulation, and phenylpropanoid biosynthesis were closely associated with innate immune responses in cotton. Kumar et al. (2016) used a combined proteomic and metabolomic approach to characterize Fusarium oxysporum mediated metabolic reprogramming of chickpea roots. Proteomic studies of the interaction between sugarcane and Sporisorium scitamineum (Barnabas et al., 2016), soybean and Fusarium virguliforme (Iqbal et al., 2016), and ashwagandha (Withania somnifera) and Alternaria alternata (Singh et al., 2017), have also been reported. Only a couple of studies utilizing a proteomic analysis, however, have been conducted in kiwifruit shoots (Petriccione et al., 2013) and leaves (Petriccione et al., 2014) in response to the canker-causing, bacterial pathogen, Pseudomonas syringae pv. actinidiae.

In the present study, an iTRAQ-based quantitative proteomic analysis, combined with gene expression and virus-induced gene silencing (VIGS), were used to identify genes associated with the infection of kiwifruit (Actinidia deliciosa “Hayward”) by B. cinerea. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first proteomic study of the kiwifruit-B. cinerea interaction, and provides information that can be used to better understand the mechanism of gray mold infection in kiwifruit.

Materials and methods

Plant material and inoculation

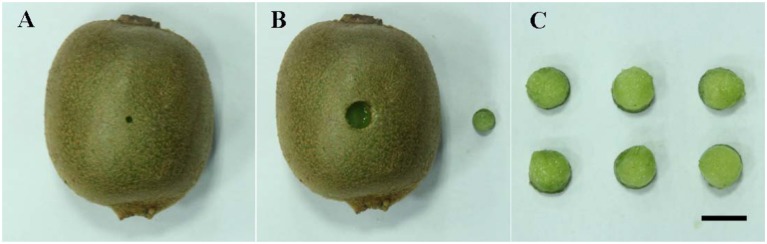

Kiwifruits (A. deliciosa “Hayward”) were harvested at 130 days after flowering from a research planting located in Xuancheng City, Anhui Province, China. The average quality parameters at the time of harvest were: 6.2° Brix, 56 N firmness, and 93 g fruit weight. Uniformly sized fruits, without wounds or rot, were selected and transported to the laboratory within 4 h after harvest. Fruits were then disinfected with 2% (v/v) sodium hypochlorite for 2 min, rinsed with tap water, and air-dried. B. cinerea, strain HFXC-16, which was originally isolated from infected kiwifruit, was grown on potato dextrose agar (PDA) for 2 weeks at 25°C (Chen et al., 2015). Two wounds (3 mm deep × 3 mm wide) were made with a sterile nail along the equator on opposite sides of each kiwifruit. Ten microliters of a B. cinerea spore suspension (1 × 104 spores mL−1) or sterile water (control) were then pipetted into each wound and allowed to dry at room temperature (25°C). Wound sites were sampled after 24 h of incubation at 25°C for the proteomic analysis, using a 9-mm cork borer under aseptic conditions. The sampled tissues were immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80°C for subsequent proteomic analysis. A representative picture of a wounded/inoculated fruit and subsequent sampled tissue are presented in Figure 1. Each sample consisted of fruit tissue pooled from 40 wounds taken from 20 fruits. The proteomic analysis utilized three biological replicates for each treatment.

Figure 1.

A representative picture showing the wounding and sampling of kiwifruit. (A) Wounded-inoculated kiwifruit prior to sampling; (B) Appearance of kiwifruit after sampled tissue was removed from inoculated kiwifruit; (C) Sampled kiwifruit tissue. Scale bar (–) represents 1 cm.

Imaging of B. cinerea disease symptom development on kiwifruit

Inoculated kiwifruit tissues were collected after 24 and 36 h of incubation at 25°C and examined under a Zeiss Axioskop microscope (Carl Zeiss, Germany). Additional observations of disease symptoms caused by B. cinerea were made after 3 days post inoculation. Three replicates (five fruits per replicate) were examined at each time point.

Protein preparation

Protein extraction from kiwifruit was performed as previously described (Liu et al., 2016). Kiwifruit sampled tissues were ground in liquid nitrogen. Proteins were extracted in a lysis buffer (7 M Urea, 2 M Thiourea, 4% CHAPS, 40 mM Tris-base, pH 8.5, 1 mM PMSF, and 2 mM EDTA), and sonicated on ice. The extracted proteins were reduced with 10 mM DTT at 56°C for 1 h and then alkylated by 55 mM iodoacetamide in the darkroom for 1 h. The reduced and alkylated protein mixtures were precipitated by adding 4 × volume of chilled acetone at −20°C overnight. After centrifugation at 30,000 g at 4°C, the pellet was dissolved in 0.5 M TEAB (Applied Biosystems, USA) and sonicated in ice. After centrifugation at 30,000 g at 4°C, an aliquot of the supernatant was taken for determination of protein concentration with a EZQ Protein Quantitation Kit (Invitrogen, USA). The proteins in the supernatant were kept at −80°C until further analysis.

iTRAQ labeling and SCX fractionation

An aliquot of total protein (100 μg) was removed from each sample solution and digested with trypsin (Promega, USA) at 37°C for 16 h using a 30:1 protein/trypsin ratio. After trypsin digestion, peptides were passed through C18 desalting columns (Nest Group Inc, USA) and subsequently lyophilized to dryness. iTRAQ labeling was performed according to the manufacturer's instructions for an 8-plex kit (Applied Biosystems). Specifically, six samples (three biological replicates from non-inoculated controls and three biological replicates from B. cinerea-inoculated samples) were iTRAQ labeled: 114-, 117-, and 119-iTRAQ tags for three control replicates; 116-, 118-, 121-iTRAQ tags for three B. cinerea-inoculated replicates. The peptides were labeled with the isobaric tags and then incubated at room temperature for 2 h. The labeled peptide mixtures were then pooled and dried by vacuum centrifugation.

SCX chromatography was performed using a LC-20AB HPLC Pump system (Shimadzu, Japan), according to Luo et al. (2015). The iTRAQ-labeled peptide mixtures were reconstituted in 4 mL of buffer A (25 mM NaH2PO4 in 25% ACN, pH 2.7) and loaded onto a 4.6 × 250 mm Ultremex SCX column containing 5-μm particles (Phenomenex, USA). The peptides were eluted at a flow rate of 1 mL per min with a gradient of buffer A for 10 min, 5–60% buffer B (25 mM NaH2PO4, 1 M KCl in 25% ACN, pH 2.7) for 27 min, and 60–100% buffer B for 1 min. The system was then maintained at 100% buffer B for 1 min before equilibrating with buffer A for 10 min prior to the next injection. Elution was monitored at absorbance of 214 nm, and fractions were collected every 1 min. The eluted peptides were pooled into 20 fractions, desalted with a Strata X C18 column (Phenomenex) and lyophilized for subsequent LC-ESI-MS/MS analysis.

LC-ESI-MS/MS analysis based on triple TOF 5600

LC-ESI-MS/MS analysis utilizing Triple TOF 5600 was conducted based on a protocol described in a previous study (Luo et al., 2015). Each fraction was resuspended in buffer A (5% ACN, 0.1% FA) and centrifuged at 20,000 g for 10 min. The final concentration of peptide was ~0.5 μg/μL. Ten micro liters of supernatant was loaded onto a 2-cm C18 trap column in a LC-20AD nano-HPLC (Shimadzu) with an auto sampler. The peptides subsequently were eluted onto a 10-cm analytical C18 column. The samples were loaded at 8 μL/min for 4 min, then a 35 min gradient was run at 300 nL/min starting from 2 to 35% buffer B (95% ACN, 0.1% FA), followed by 5 min linear gradient to 60%, followed by a 2 min linear gradient to 80%, and maintenance at 80% buffer B for 4 min, and finally returned to 5% in 1 min.

Data was acquired using an ion spray voltage of 2.5 kV, curtain gas of 30 psi, and nebulizer gas of 15 psi at an interface heater temperature of 150°C on a TripleTOF 5600 System (AB SCIEX, USA) fitted with a Nanospray III source (AB SCIEX) and a pulled quartz tip as the emitter (New Objectives, USA). The MS was operated with a RP of ≥ 30,000 FWHM for TOF MS scans. Survey scans for IDA were acquired in 250 ms, and 30 product ion scans were collected if the scans exceeded a threshold of 120 counts per second with a 2+ to 5+ charge-state. Total cycle time was set to 3.3 s. The Q2 transmission window was 100 Da for 100%. Four time bins were summed for each scan at a pulser frequency value of 11 kHz by monitoring the 40 GHz multi channel TDC detector with a four-anode channel ion detector. A sweeping collision energy setting of 35 ± 5 eV, coupled with iTRAQ adjust rolling collision energy, was applied to precursor ions for collision-induced dissociation. Dynamic exclusion was set for 1/2 of peak width (15 s), and the precursor was subsequently refreshed off the exclusion list.

Proteomic data analysis

Raw data files acquired from Triple TOF 5600 were converted into MGF files using Proteome Discoverer 1.2 (Thermo, Germany), and the MGF files were queried. Protein identification was performed using the Mascot search engine v.2.3.02 (Matrix Science, UK) against a database derived from the Kiwifruit Genome, which includes 39,040 protein sequences (http://bioinfo.bti.cornell.edu/cgi-bin/kiwi/download.cgi).

Proteins were identified using a mass tolerance of ±0.05 Da (ppm) that was allowed for intact peptide masses and ±0.1 Da for fragmented ions, with an allowance for one missed cleavage in the trypsin digests. Gln->pyro-Glu (N-term Q), Oxidation (M), and deamidated (NQ) were selected as potential variable modifications, while carbamidomethyl (C), iTRAQ8plex (N-term), and iTRAQ8plex (K) were selected as fixed modifications. The charge states of peptides were set to +2 and +3. Specifically, an automatic decoy database search was performed in Mascot, along with a search of the real database, by choosing the decoy checkbox in which a random sequence of the database was generated and tested for raw spectra. Only peptides with significance scores (≥20) at the 99% confidence interval by a Mascot probability analysis greater than “identity” were counted as identified in order to reduce the probability of false peptide identification. Each confident protein identification required at least one unique peptide. The false discovery rate (FDR) of identified proteins was ≤ 0.01.

For protein quantization, a protein was required to contain at least two unique peptides. The quantitative protein ratios were weighted and normalized by the median ratio in Mascot. Only ratios with P < 0.05, according to a Student's t-test, were employed, and only fold-changes >1.33 were considered as significant. Functional annotation of the proteins was conducted using Blast2GO (https://www.blast2go.com/) against the NCBI non-redundant protein database. The KEGG (http://www.genome.jp/kegg/) and COG databases (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/COG/) were used to classify the identified proteins. In order to provide clarity, a workflow diagram regarding the above experimental procedure from protein extraction to proteomic data analysis has been shown in Figure S1. The mass spectrometry proteomics data have been deposited to the ProteomeXchange Consortium via the PRIDE (Vizcaino et al., 2016) partner repository with the dataset identifier PXD008589.

RT-qPCR analysis

Tissue samples were collected from fruit subjected to the same treatment conditions described for the proteomic analysis. Approximately 500 mg of fruit tissue from each sample was frozen and ground in liquid nitrogen. Total RNA was extracted using a Plant Total RNA Isolation Kit (Biofit Tech, China). The extracted RNA was treated with DNase, and purified using an EasyPure Plant RNA Kit (TransGen Biotech, China). First-strand cDNAs were synthesized using TransScript One-Step gDNA Removal and cDNA Synthesis SuperMix (TransGen Biotech). The resulting cDNAs were used for RT-qPCR analysis following the manufacturer's protocol. Briefly, each RT-qPCR reaction was carried out in a 20 μL reaction containing 10 μL of TransStart® Top Green PCR Master Mix (TransGen Biotech) and 0.4 μL of each PCR primer at 10 μM. The RT-qPCR was conducted on a ABI StepOne Plus (Applied Biosystems) using the following cycling conditions: 95°C for 30 s, followed by 40 cycles of 95°C for 5 s and 60°C for 20 s. Nine genes were selected for verification based on their pattern of differential expression revealed in the iTRAQ analysis. EF1α and Actin genes were used as internal controls (Nieuwenhuizen et al., 2009; Li et al., 2010), and relative expression was calculated using the 2−ΔΔCT method. Melting curve analyses of amplification products were performed at the end of each PCR reaction to ensure that unique products were amplified. PCR products were cloned and sequenced to verify their identity. The gene-specific primer pairs used for each gene are listed in Table S1. Each of the treatment groups consisted of three biological replicates, and the experiment was repeated three times. A Student's t-test was used to determine whether the relative difference between sample groups (B. cinerea-inoculated vs. water-inoculated, control kiwifruits) was statistically significant (P < 0.05).

Vigs of Myosin 10 in kiwifruit

VIGS of Myosin10 was carried out as previously described (Liu et al., 2014). Kiwifruits obtained from the same collection of fruits used in the proteomic and RT-qPCR analyses were also used for the VIGS experiment. These fruits were harvested at 130 days after flowering. Myosin 10 was PCR-amplified from kiwifruit cDNA using the primers: F, 5′-TCTAGAGAAACGAACAGAGATAAAATCAGAC-3′; R, 5′-CTCGAGCGCCTGTAAGGGACAAAAG-3′, with Xba I and XhoI sites (underlined) added to each end, respectively. The amplified PCR product was cloned into the pTRV2 vector and the resulting CaMV 35S promoter-driven constructs were subsequently introduced into Agrobacterium tumefaciens strain GV3101. Freshly-grown cultures of the transformed A. tumefaciens carrying the pTRV2 vector were mixed 1:1 with A. tumefaciens GV3101 carrying the pTRV1 vector. The mixed Agrobacterium cultures containing pTRV2:CaMyosin10 and pTRV1 (OD600 of 0.8) were syringe-injected into kiwifruit. Mixed Agrobacterium cultures containing pTRV2 (empty vector) and pTRV1 served as a control.

Seven days after Agrobacterium injection, B. cinerea spores (10 μL containing 1 × 104 spores mL−1) were inoculated into the same wounds as those created by the previously injected Agrobacterium. In order to maintain a high relative humidity (~85%), the treated kiwifruit were placed in covered plastic food trays enclosed in polyethylene bags and stored at 25°C in a programmable environmental chamber with a temperature and humidity control system (Sanyo, Japan). Disease symptoms caused by B. cinerea became apparent after 60 h of storage, and kiwifruit tissues were collected at that time for Myosin 10 expression analysis. The experimental design consisted of three replicates of 10 fruits (two wounds per fruit) for each treatment. The experiment was repeated three times.

Results and discussion

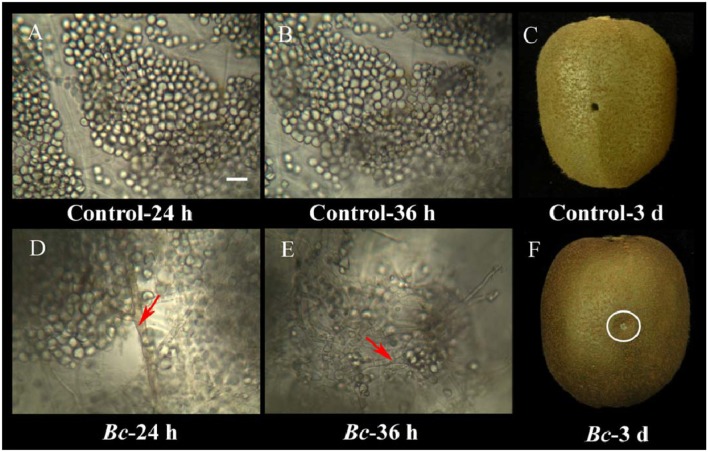

Development of B. cinerea infection in kiwifruit

B. cinerea infection of kiwifruit was clearly evident in the 3-day period of examination (Figure 2). While the kiwifruit tissue in the water-inoculated control remained intact during the 3-day storage at 25°C (Figures 2A–C), B. cinerea hyphae were easily observed at 24 h after inoculation in the pathogen-inoculated samples, however, the majority of the fruit cells did not appear to be degraded (Figure 2D). Based on these observations, a 24 h time point was selected for the proteomic analysis. After 24 h, fruit cells in the B. cinerea-inoculated samples appeared degraded, and B. cinerea hyphae were well established by 36 h after inoculation (Figure 2E). Macroscopic symptoms of gray mold infection of kiwifruit were readily apparent by 3 days after inoculation (Figure 2F).

Figure 2.

Microscopic observations of the interaction between kiwifruit and B. cinerea during the early stages of the infection process. Control kiwifruit tissue (inoculated with sterile water) at 24 h (A) and 36 h (B), as well as whole fruit at 3 days post-inoculation (C). Kiwifruit tissue that had been inoculated with B. cinerea at 24 h (D) and 36 h (E), and whole fruit at 3-days (F). Red arrows indicate B. cinerea hyphae. The wound inoculated with B. cinerea is in the area within the white circle. Scale bar (–) represents 10 μm, and is applicable to (A–E).

Proteomic analysis of kiwifruit in response to B. cinerea

Using iTRAQ and LC-ESI-MS/MS, a total of 2,487 kiwifruit proteins were identified against a database derived from the Kiwifruit Genome (http://bioinfo.bti.cornell.edu/cgi-bin/kiwi/download.cgi) (Table S2). In addition, 113 B. cinerea proteins were identified against a B. cinerea database in Uniprot (http://www.uniprot.org/uniprot/?query=%09Botryotinia+fuckeliana+&sort=score). The source should be the spores in the wound-site samples, though the amount of fungal biomass was little. The present study, however, focused on the response of kiwifruit to B. cinerea. The kiwifruit proteins were further investigated in the following studies.

A value of 33% fold-difference (B. cinerea inoculation vs. water control) was used to identify differentially accumulated proteins (DAPs) within the obtained kiwifruit protein dataset. This percentage of fold-change identified proteins that had significantly (P < 0.05) increased (1.33-fold) or decreased (0.75-fold) in their level of accumulation. Based upon these criteria, 196 proteins with increased and 96 proteins with decreased levels of accumulation were identified (Table 1).

Table 1.

List of the 196 kiwifruit proteins that exhibited an increase in their level of accumulation in response to infection by B. cinerea, and the 96 proteins that decrease in their level of accumulation in response to infection.

| No. | Hits | Accession | Description | Fold change (mean ± SD) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2277 | Achn064441 | Pectinesterase | 4.02 ± 0.27 |

| 2 | 1148 | Achn007441 | Putative 60S ribosomal protein L35 | 3.54 ± 0.47 |

| 3 | 2317 | Achn241831 | UDP-glycosyltransferase 1 | 2.78 ± 0.73 |

| 4 | 557 | Achn188281 | Late embryogenesis abundant hydroxyproline-rich glycoprotein | 2.64 ± 0.57 |

| 5 | 2092 | Achn254861 | Proactivator polypeptide | 2.61 ± 0.20 |

| 6 | 867 | Achn356861 | Oxygen-evolving enhancer protein 3-2 | 2.56 ± 0.11 |

| 7 | 793 | Achn024621 | Epoxide hydrolase 2 | 2.43 ± 0.17 |

| 8 | 277 | Achn126481 | Polygalacturonase-inhibitor protein | 2.43 ± 0.39 |

| 9 | 1909 | Achn129791 | 40S ribosomal protein S21 | 2.42 ± 0.91 |

| 10 | 1139 | Achn011001 | Pectinesterase | 2.30 ± 0.05 |

| 11 | 2331 | Achn064451 | Pectinesterase | 2.28 ± 0.43 |

| 12 | 2344 | Achn012841 | 60S ribosomal protein L26 | 2.23 ± 0.46 |

| 13 | 2356 | Achn370161 | 60S ribosomal protein L3; putative | 2.21 ± 0.04 |

| 14 | 2126 | Achn228701 | Acyl-CoA binding protein 6 | 2.18 ± 0.60 |

| 15 | 2300 | Achn350811 | 60S ribosomal protein L17 | 2.14 ± 0.11 |

| 16 | 1221 | Achn183331 | 60S ribosomal protein L21 | 2.13 ± 0.18 |

| 17 | 20 | Achn061151 | Charged multivesicular body protein 4b; putative | 2.11 ± 0.68 |

| 18 | 1683 | Achn384861 | Inositol monophosphatase family protein | 2.05 ± 0.96 |

| 19 | 1197 | Achn174791 | 60S ribosomal protein L17 | 2.03 ± 0.13 |

| 20 | 1836 | Achn244961 | Putative polyvinylalcohol dehydrogenase | 2.02 ± 0.19 |

| 21 | 2000 | Achn331551 | Myosin-11 | 2.01 ± 0.39 |

| 22 | 223 | Achn163511 | Proton pump interactor 1 | 1.98 ± 0.18 |

| 23 | 130 | Achn153551 | 30S ribosomal protein S12; related | 1.96 ± 0.16 |

| 24 | 2084 | Achn008021 | 60S ribosomal protein L23a; putative | 1.96 ± 0.05 |

| 25 | 760 | Achn065911 | 40S ribosomal protein S11; putative | 1.94 ± 0.61 |

| 26 | 616 | Achn304291 | 50S ribosomal protein L2 | 1.94 ± 0.29 |

| 27 | 1920 | Achn170451 | Methionine aminopeptidase | 1.92 ± 0.60 |

| 28 | 1382 | Achn007231 | At2g31160/T16B12.3 | 1.91 ± 0.27 |

| 29 | 1574 | Achn007361 | Histone H4 | 1.90 ± 0.24 |

| 30 | 1274 | Achn159241 | Subtilisin-like protease | 1.89 ± 0.16 |

| 31 | 2202 | Achn223851 | Cyclin-dependent kinase A | 1.87 ± 0.20 |

| 32 | 213 | Achn058851 | Subtilisin-like protease | 1.86 ± 0.49 |

| 33 | 940 | Achn278601 | Reticulon family protein | 1.86 ± 0.30 |

| 34 | 1520 | Achn032271 | Ubiquitin/ribosomal protein S27a | 1.85 ± 0.57 |

| 35 | 826 | Achn228711 | Ubiquinol oxidase | 1.84 ± 0.18 |

| 36 | 1557 | Achn081501 | Remorin; putative | 1.82 ± 0.07 |

| 37 | 1597 | Achn127311 | Small ubiquitin-related modifier 2 | 1.82 ± 0.23 |

| 38 | 362 | Achn092681 | Hsc70-interacting protein | 1.82 ± 0.27 |

| 39 | 1422 | Achn128371 | 60S ribosomal protein L3; putative | 1.81 ± 0.36 |

| 40 | 2343 | Achn191291 | 40S ribosomal protein S26; putative | 1.81 ± 0.29 |

| 41 | 137 | Achn291371 | Leucine-rich repeat receptor-like serine/threonine-protein kinase | 1.80 ± 0.26 |

| 42 | 255 | Achn337171 | Mitochondrial import inner membrane translocase subunit tim9 | 1.79 ± 0.18 |

| 43 | 956 | Achn304031 | Cytochrome P450; putative | 1.79 ± 0.41 |

| 44 | 373 | Achn269851 | Putative serine carboxypeptidase | 1.78 ± 0.11 |

| 45 | 1368 | Achn190951 | Adenosylhomocysteinase | 1.78 ± 0.68 |

| 46 | 517 | Achn331491 | Reticulon family protein | 1.77 ± 0.08 |

| 47 | 1721 | Achn132881 | Myosin-10 | 1.77 ± 0.04 |

| 48 | 2001 | Achn330021 | Prefoldin subunit; putative | 1.77 ± 0.24 |

| 49 | 1174 | Achn155131 | Syntaxin | 1.77 ± 0.53 |

| 50 | 2351 | Achn052551 | V-type proton ATPase subunit G 1 | 1.76 ± 0.22 |

| 51 | 1798 | Achn026511 | Ribosomal protein L15 | 1.75 ± 0.14 |

| 52 | 2458 | Achn358621 | Heavy-metal-associated domain-containing protein; putative; expressed | 1.74 ± 0.12 |

| 53 | 2354 | Achn089541 | Stress-induced-phosphoprotein | 1.73 ± 0.11 |

| 54 | 1097 | Achn001561 | Stress-induced-phosphoprotein | 1.72 ± 0.29 |

| 55 | 257 | Achn151071 | Adenosylhomocysteinase | 1.72 ± 0.63 |

| 56 | 45 | Achn058601 | Protein grpE; putative | 1.71 ± 0.03 |

| 57 | 782 | Achn343961 | Dehydrin 2 | 1.70 ± 0.51 |

| 58 | 941 | Achn147681 | Ly 5~-AMP-activated protein kinase beta-1 subunit-related | 1.70 ± 0.41 |

| 59 | 1458 | Achn348701 | Lysosomal alpha-mannosidase; putative | 1.69 ± 0.27 |

| 60 | 1760 | Achn149381 | Harpin inducing protein | 1.69 ± 0.45 |

| 61 | 237 | Achn290561 | 60S ribosomal protein L3; putative | 1.68 ± 0.14 |

| 62 | 1783 | Achn183021 | Putative regulator of chromosome condensation; 48393-44372 | 1.68 ± 0.45 |

| 63 | 1809 | Achn323431 | Kinase family protein | 1.68 ± 0.39 |

| 64 | 335 | Achn281881 | Putative subtilisin-like protease | 1.67 ± 0.07 |

| 65 | 1949 | Achn246321 | Polygalacturonase-inhibitor protein | 1.67 ± 0.11 |

| 66 | 175 | Achn231901 | 60S ribosomal protein L18a | 1.65 ± 0.26 |

| 67 | 2413 | Achn105821 | Calcium-binding EF hand family protein | 1.65 ± 0.17 |

| 68 | 1398 | Achn112171 | RNA polymerase II C-terminal domain phosphatase-like protein | 1.64 ± 0.38 |

| 69 | 615 | Achn293101 | Guanine nucleotide exchange factor | 1.64 ± 0.38 |

| 70 | 778 | Achn135031 | Serine carboxypeptidase; putative | 1.64 ± 0.25 |

| 71 | 1695 | Achn036091 | 60S ribosomal protein L35a | 1.64 ± 0.15 |

| 72 | 1526 | Achn153791 | Phenylalanine ammonia-lyase | 1.64 ± 0.17 |

| 73 | 1496 | Achn124041 | 30S ribosomal protein S5 | 1.63 ± 0.28 |

| 74 | 1553 | Achn216701 | 60S ribosomal protein L7; putative | 1.62 ± 0.18 |

| 75 | 1989 | Achn011841 | Late embryogenesis abundant hydroxyproline-rich glycoprotein | 1.62 ± 0.24 |

| 76 | 1934 | Achn386391 | Ribosomal protein L19 | 1.60 ± 0.35 |

| 77 | 1094 | Achn250781 | 40S ribosomal protein S13; putative | 1.59 ± 0.41 |

| 78 | 879 | Achn078681 | 60S ribosomal protein L13a; putative | 1.59 ± 0.19 |

| 79 | 1013 | Achn107321 | Pectinesterase-2; putative | 1.58 ± 0.27 |

| 80 | 518 | Achn144051 | Glutathione S-transferase 1 | 1.58 ± 0.24 |

| 81 | 2187 | Achn020161 | Laccase-like protein | 1.58 ± 0.36 |

| 82 | 2475 | Achn048361 | Serine-threonine protein kinase | 1.58 ± 0.39 |

| 83 | 1901 | Achn074971 | Pectin acetylesterase | 1.57 ± 0.41 |

| 84 | 127 | Achn363441 | Lysosomal Pro-X carboxypeptidase | 1.57 ± 0.21 |

| 85 | 1357 | Achn261051 | Dynamin-2B | 1.57 ± 0.29 |

| 86 | 1138 | Achn178831 | Translocon-associated protein; alpha subunit; putative | 1.56 ± 0.26 |

| 87 | 1647 | Achn312631 | Aldehyde dehydrogenase; putative | 1.55 ± 0.16 |

| 88 | 1839 | Achn038071 | Cytochrome P450; putative | 1.54 ± 0.52 |

| 89 | 1393 | Achn226071 | 60S ribosomal protein L7; putative | 1.54 ± 0.24 |

| 90 | 2384 | Achn083081 | 50S ribosomal protein L2 | 1.53 ± 0.46 |

| 91 | 2314 | Achn054521 | Unknown protein | 1.53 ± 0.52 |

| 92 | 41 | Achn051951 | Mitochondrial carrier-like protein | 1.53 ± 0.44 |

| 93 | 360 | Achn349511 | NADH oxidoreductase F subunit | 1.52 ± 0.19 |

| 94 | 1433 | Achn228601 | WD-repeat protein; putative | 1.52 ± 0.41 |

| 95 | 47 | Achn180221 | Heat stress transcription factor A-5 | 1.52 ± 0.50 |

| 96 | 885 | Achn178681 | Ammonium transporter | 1.52 ± 0.56 |

| 97 | 1099 | Achn198781 | Myosin-like protein | 1.51 ± 0.56 |

| 98 | 1081 | Achn118801 | Senescence-associated protein | 1.51 ± 0.19 |

| 99 | 2411 | Achn216951 | Histidine-tRNA ligase | 1.51 ± 0.41 |

| 100 | 379 | Achn061701 | Cathepsin B-like cysteine proteinase 1 | 1.50 ± 0.06 |

| 101 | 1529 | Achn180381 | Bromodomain protein | 1.50 ± 0.52 |

| 102 | 1751 | Achn043281 | Transferase; transferring glycosyl groups; putative | 1.49 ± 0.28 |

| 103 | 2151 | Achn097151 | Protein phosphatase 2c; putative | 1.49 ± 0.37 |

| 104 | 76 | Achn374871 | Tetratricopeptide repeat-containing protein (Precursor) | 1.49 ± 0.27 |

| 105 | 1999 | Achn074221 | 60S ribosomal protein L27A | 1.49 ± 0.17 |

| 106 | 1795 | Achn151811 | Photosystem II protein Psb27 | 1.49 ± 0.17 |

| 107 | 1607 | Achn174421 | Elongation factor 1 beta | 1.49 ± 0.22 |

| 108 | 1854 | Achn127771 | Mitochondrial import receptor subunit TOM9-2 | 1.48 ± 0.40 |

| 109 | 92 | Achn079561 | Heat shock protein 90-2 | 1.48 ± 0.27 |

| 110 | 153 | Achn199371 | Phospholipid-transporting ATPase; putative | 1.48 ± 0.15 |

| 111 | 326 | Achn078621 | Pantothenate synthetase | 1.48 ± 0.45 |

| 112 | 139 | Achn349381 | Anthranilate N-benzoyltransferase protein; putative | 1.47 ± 0.15 |

| 113 | 423 | Achn225821 | ABI3-interacting protein 2 | 1.47 ± 0.23 |

| 114 | 1654 | Achn151591 | CASP-like protein | 1.47 ± 0.12 |

| 115 | 1299 | Achn019431 | Aquaporin | 1.46 ± 0.18 |

| 116 | 1168 | Achn313721 | Purple acid phosphatase 1 | 1.46 ± 0.28 |

| 117 | 586 | Achn112731 | Serine carboxypeptidase; putative | 1.46 ± 0.27 |

| 118 | 995 | Achn048881 | Eukaryotic translation initiation factor; putative | 1.46 ± 0.05 |

| 119 | 691 | Achn121661 | ATP-binding cassette transporter 1 | 1.46 ± 0.20 |

| 120 | 9 | Achn197261 | Proteasome subunit alpha type | 1.46 ± 0.14 |

| 121 | 1804 | Achn094391 | Developmentally regulated GTP-binding protein; putative | 1.46 ± 0.49 |

| 122 | 2188 | Achn074681 | Cytochrome c; putative | 1.46 ± 0.19 |

| 123 | 2107 | Achn085281 | Dihydropyrimidinase; putative | 1.45 ± 0.22 |

| 124 | 198 | Achn388771 | WD-40 repeat-containing protein | 1.45 ± 0.33 |

| 125 | 1750 | Achn332471 | Myosin-10 | 1.45 ± 0.08 |

| 126 | 1341 | Achn146501 | Metacaspase 1 | 1.45 ± 0.17 |

| 127 | 2396 | Achn252451 | Outer envelope pore protein 37; chloroplastic | 1.45 ± 0.43 |

| 128 | 356 | Achn039991 | 60S ribosomal protein L5 | 1.45 ± 0.06 |

| 129 | 1416 | Achn274341 | 60S ribosomal protein L22-like protein | 1.45 ± 0.10 |

| 130 | 2007 | Achn361381 | Calcineurin B-like protein 2 | 1.45 ± 0.12 |

| 131 | 1972 | Achn022101 | Amine oxidase | 1.44 ± 0.37 |

| 132 | 1775 | Achn274801 | 60S ribosomal protein L13 | 1.43 ± 0.29 |

| 133 | 55 | Achn261991 | 3-hydroxyacyl-[acyl-carrier-protein] dehydratase FabZ | 1.42 ± 0.24 |

| 134 | 1005 | Achn186181 | RING-H2 finger protein RHF2a; putative; expressed | 1.42 ± 0.55 |

| 135 | 663 | Achn345701 | 50S ribosomal protein L5 | 1.42 ± 0.15 |

| 136 | 1580 | Achn334211 | Probable potassium transport system protein kup | 1.42 ± 0.23 |

| 137 | 1507 | Achn082021 | Protein disulfide isomerase; putative | 1.42 ± 0.39 |

| 138 | 2474 | Achn288981 | NADH dehydrogenase 1 alpha subcomplex subunit 13 | 1.42 ± 0.32 |

| 139 | 755 | Achn314741 | Cytochrome P450 | 1.42 ± 0.30 |

| 140 | 402 | Achn389291 | Ras-related protein Rab-2-A | 1.41 ± 0.17 |

| 141 | 1743 | Achn132141 | T-complex protein 1 subunit beta | 1.41 ± 0.30 |

| 142 | 613 | Achn246001 | Nascent polypeptide-associated complex subunit alpha-like protein | 1.41 ± 0.15 |

| 143 | 436 | Achn034101 | LETM1 and EF-hand domain-containing protein 1; mitochondrial | 1.41 ± 0.27 |

| 144 | 2171 | Achn011061 | Exocyst complex protein EXO70 | 1.41 ± 0.26 |

| 145 | 2042 | Achn281431 | Polyadenylate-binding protein; putative | 1.41 ± 0.33 |

| 146 | 415 | Achn006331 | Cathepsin B-like cysteine proteinase 1 | 1.40 ± 0.34 |

| 147 | 413 | Achn017571 | Phosphoesterase family protein | 1.40 ± 0.10 |

| 148 | 758 | Achn107611 | 60S ribosomal protein L12; putative | 1.40 ± 0.20 |

| 149 | 2282 | Achn214241 | U1 small nuclear ribonucleoprotein A | 1.40 ± 0.15 |

| 150 | 619 | Achn116721 | Soul heme-binding family protein | 1.40 ± 0.32 |

| 151 | 728 | Achn068571 | Ribosomal protein | 1.39 ± 0.18 |

| 152 | 491 | Achn032901 | 60S ribosomal protein L6 | 1.39 ± 0.22 |

| 153 | 1957 | Achn198661 | Developmentally regulated GTP binding protein | 1.39 ± 0.22 |

| 154 | 1413 | Achn106831 | ATP-dependent Clp protease proteolytic subunit | 1.39 ± 0.53 |

| 155 | 94 | Achn383281 | 17.6 kDa class II heat shock protein | 1.39 ± 0.41 |

| 156 | 418 | Achn311841 | Putative Molybdopterin binding; CinA-related | 1.39 ± 0.06 |

| 157 | 585 | Achn089941 | DS synthase | 1.38 ± 0.07 |

| 158 | 1082 | Achn294771 | Coatomer alpha subunit; putative | 1.38 ± 0.38 |

| 159 | 1573 | Achn106461 | Xyloglucan-specific endoglucanase inhibitor protein | 1.38 ± 0.17 |

| 160 | 2311 | Achn341571 | Calcium-binding protein; putative | 1.38 ± 0.06 |

| 161 | 1004 | Achn306081 | Trigger factor; putative | 1.38 ± 0.29 |

| 162 | 1747 | Achn081801 | ATP synthase D chain; mitochondrial; putative | 1.38 ± 0.06 |

| 163 | 1324 | Achn191071 | Beta-galactosidase | 1.37 ± 0.14 |

| 164 | 1484 | Achn076861 | Pre-mRNA-splicing factor CDC5/CEF1 | 1.37 ± 0.29 |

| 165 | 228 | Achn047911 | Alpha-glucosidase | 1.37 ± 0.21 |

| 166 | 2064 | Achn373051 | Putative glycine-rich RNA binding protein-like | 1.37 ± 0.06 |

| 167 | 1070 | Achn132631 | Thaumatin-like protein | 1.37 ± 0.13 |

| 168 | 2432 | Achn175401 | Importin subunit alpha | 1.37 ± 0.38 |

| 169 | 951 | Achn073761 | Reductase 2 | 1.37 ± 0.23 |

| 170 | 2303 | Achn106551 | Alpha-glucosidase; putative | 1.37 ± 0.03 |

| 171 | 1635 | Achn368611 | FAD-binding domain-containing protein | 1.36 ± 0.23 |

| 172 | 847 | Achn022471 | Kiwellin | 1.36 ± 0.07 |

| 173 | 133 | Achn191551 | 60S ribosomal protein L10; putative | 1.36 ± 0.20 |

| 174 | 421 | Achn314841 | Proteasome subunit beta type | 1.36 ± 0.32 |

| 175 | 316 | Achn011721 | Chaperone protein HtpG | 1.36 ± 0.17 |

| 176 | 2355 | Achn117921 | U-box domain-containing protein 4 | 1.36 ± 0.18 |

| 177 | 935 | Achn099221 | Myosin-11 | 1.36 ± 0.18 |

| 178 | 674 | Achn178911 | Cold shock protein-1 | 1.35 ± 0.31 |

| 179 | 419 | Achn202631 | Protein disulfide isomerase L-2 | 1.35 ± 0.08 |

| 180 | 813 | Achn087251 | 14-3-3-like protein GF14 Epsilon | 1.35 ± 0.10 |

| 181 | 1117 | Achn036141 | Acetyl-coenzyme A carboxylase carboxyl transferase subunit alpha | 1.35 ± 0.32 |

| 182 | 1796 | Achn105661 | Malic enzyme | 1.35 ± 0.33 |

| 183 | 1204 | Achn249061 | HEAT repeat-containing protein 7A | 1.34 ± 0.11 |

| 184 | 1604 | Achn321291 | Photosystem II D2 protein | 1.34 ± 0.20 |

| 185 | 1383 | Achn355261 | Cathepsin L-like cysteine proteinase | 1.34 ± 0.14 |

| 186 | 1944 | Achn285271 | Lactoylglutathione lyase; putative | 1.34 ± 0.28 |

| 187 | 2137 | Achn386611 | Galactokinase; putative | 1.34 ± 0.18 |

| 188 | 665 | Achn300151 | Arginine/serine-rich splicing factor; putative | 1.34 ± 0.11 |

| 189 | 1119 | Achn085181 | Cop9 signalosome complex subunit; putative | 1.34 ± 0.41 |

| 190 | 337 | Achn115381 | Myosin-like protein | 1.33 ± 0.15 |

| 191 | 834 | Achn071381 | Chaperone protein htpG family protein | 1.33 ± 0.17 |

| 192 | 336 | Achn368931 | Cytochrome P450 | 1.33 ± 0.36 |

| 193 | 1579 | Achn358641 | Remorin; putative | 1.33 ± 0.07 |

| 194 | 1969 | Achn353791 | 60S ribosomal protein L7a; putative | 1.33 ± 0.03 |

| 195 | 267 | Achn061131 | Hydrogen-transporting ATP synthase; rotational mechanism; putative | 1.33 ± 0.21 |

| 196 | 1464 | Achn053521 | Major latex-like protein | 1.33 ± 0.07 |

| 197 | 179 | Achn042071 | Trafficking protein particle complex subunit | 0.75 ± 0.07 |

| 198 | 26 | Achn087361 | Endoplasmic reticulum-Golgi intermediate compartment protein; putative | 0.75 ± 0.12 |

| 199 | 2330 | Achn309541 | Calcineurin B subunit; putative | 0.75 ± 0.06 |

| 200 | 2443 | Achn166171 | Aquaporin protein 4 | 0.75 ± 0.03 |

| 201 | 822 | Achn314971 | 4-hydroxy-tetrahydrodipicolinate synthase | 0.75 ± 0.11 |

| 202 | 562 | Achn133811 | Protein transport protein Sec61 subunit alpha | 0.75 ± 0.16 |

| 203 | 2143 | Achn185021 | Mitochondrial outer membrane protein porin | 0.75 ± 0.08 |

| 204 | 303 | Achn063231 | Choline-phosphate cytidylyltransferase | 0.75 ± 0.10 |

| 205 | 2393 | Achn249721 | Glutamate dehydrogenase | 0.74 ± 0.05 |

| 206 | 1069 | Achn288091 | Prohibitin | 0.74 ± 0.22 |

| 207 | 1669 | Achn283331 | UDP-glucosyltransferase; putative | 0.74 ± 0.07 |

| 208 | 1151 | Achn162311 | Reductase 1 | 0.74 ± 0.19 |

| 209 | 54 | Achn230831 | Wound/stress protein | 0.74 ± 0.19 |

| 210 | 556 | Achn196701 | 4-coumarate CoA ligase | 0.74 ± 0.20 |

| 211 | 1589 | Achn303631 | Ran-binding protein 1 | 0.74 ± 0.17 |

| 212 | 1590 | Achn269171 | Probable UDP-arabinopyranose mutase 5 | 0.74 ± 0.08 |

| 213 | 1831 | Achn235831 | Beta-glucosidase | 0.74 ± 0.12 |

| 214 | 862 | Achn170351 | Nudix hydrolase | 0.73 ± 0.12 |

| 215 | 1178 | Achn194491 | N-carbamoyl-L-amino acid hydrolase (L-carbamoylase) | 0.73 ± 0.04 |

| 216 | 2262 | Achn285991 | Glutathione peroxidase | 0.73 ± 0.05 |

| 217 | 1241 | Achn069551 | Arginine–tRNA ligase | 0.73 ± 0.16 |

| 218 | 1329 | Achn193181 | T-complex protein 1 subunit zeta | 0.73 ± 0.05 |

| 219 | 535 | Achn324111 | Glycine cleavage system h protein; putative | 0.73 ± 0.07 |

| 220 | 545 | Achn065851 | Cysteine-tRNA ligase | 0.73 ± 0.21 |

| 221 | 970 | Achn369161 | Proteasome subunit beta type | 0.73 ± 0.21 |

| 222 | 1832 | Achn095061 | Dolichyl-diphosphooligosaccharide-protein glycosyltransferase subunit | 0.73 ± 0.08 |

| 223 | 1628 | Achn313711 | Annexin | 0.73 ± 0.06 |

| 224 | 645 | Achn311291 | Glutamine-tRNA ligase; contains IPR000924 (Glutamyl/glutaminyl-tRNA synthetase; class Ib); IPR00763 | 0.73 ± 0.16 |

| 225 | 2339 | Achn276041 | Cystathionine beta-lyase | 0.73 ± 0.14 |

| 226 | 1887 | Achn317471 | Pectinesterase inhibitor | 0.73 ± 0.04 |

| 227 | 777 | Achn122461 | Aldehyde dehydrogenase | 0.73 ± 0.10 |

| 228 | 2174 | Achn022881 | Proteasome subunit beta type | 0.72 ± 0.11 |

| 229 | 1938 | Achn296481 | Sulfurtransferase | 0.72 ± 0.25 |

| 230 | 1684 | Achn161931 | UDP-glucose 6-dehydrogenase | 0.72 ± 0.01 |

| 231 | 2198 | Achn284371 | Putative delta subunit of ATP synthase | 0.72 ± 0.04 |

| 232 | 874 | Achn283441 | Cyclase-like protein | 0.72 ± 0.16 |

| 233 | 2108 | Achn016261 | Adenylosuccinate synthetase | 0.71 ± 0.07 |

| 234 | 37 | Achn001821 | Thaumatin-like protein | 0.71 ± 0.10 |

| 235 | 681 | Achn047661 | Putative RNA-binding protein | 0.71 ± 0.17 |

| 236 | 766 | Achn254211 | Endoplasmic reticulum-Golgi intermediate compartment protein; putative | 0.71 ± 0.13 |

| 237 | 1289 | Achn339141 | Malate dehydrogenase | 0.71 ± 0.06 |

| 238 | 308 | Achn052701 | Superoxide dismutase [Cu-Zn] | 0.71 ± 0.09 |

| 239 | 2377 | Achn358201 | Arginine–tRNA ligase | 0.71 ± 0.07 |

| 240 | 74 | Achn280061 | Alcohol dehydrogenase; zinc-containing | 0.71 ± 0.07 |

| 241 | 151 | Achn006921 | mRNA-decapping enzyme 2 | 0.71 ± 0.11 |

| 242 | 1821 | Achn230841 | Wound/stress protein | 0.71 ± 0.01 |

| 243 | 795 | Achn237571 | Dihydroxy-acid dehydratase; putative | 0.71 ± 0.09 |

| 244 | 1093 | Achn305831 | Phosphoglycerate kinase | 0.71 ± 0.14 |

| 245 | 865 | Achn227161 | Patatin-like protein 3 | 0.70 ± 0.10 |

| 246 | 725 | Achn364961 | Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase | 0.70 ± 0.11 |

| 247 | 2284 | Achn147891 | Cysteine desulfurase | 0.70 ± 0.20 |

| 248 | 476 | Achn073781 | Alpha-glucan water dikinase | 0.70 ± 0.06 |

| 249 | 1060 | Achn008501 | ADP-ribosylation factor | 0.69 ± 0.09 |

| 250 | 1215 | Achn147711 | Oligopeptidase A; putative | 0.69 ± 0.13 |

| 251 | 1298 | Achn239461 | Pyruvate kinase | 0.69 ± 0.26 |

| 252 | 2371 | Achn034821 | Cytochrome P450; putative | 0.69 ± 0.12 |

| 253 | 1866 | Achn061751 | Glucose-1-phosphate adenylyltransferase | 0.69 ± 0.06 |

| 254 | 1519 | Achn019301 | Non-imprinted in Prader-Willi/Angelman syndrome region protein; putative | 0.69 ± 0.03 |

| 255 | 2352 | Achn349661 | Glucose-6-phosphate 1-dehydrogenase | 0.69 ± 0.14 |

| 256 | 499 | Achn184951 | Aspartokinase-homoserine dehydrogenase | 0.68 ± 0.06 |

| 257 | 437 | Achn077201 | Glycogenin; putative | 0.67 ± 0.24 |

| 258 | 192 | Achn276181 | Putative ferredoxin-dependent glutamate synthase 1 | 0.67 ± 0.06 |

| 259 | 1135 | Achn268151 | Acyl-CoA thioesterase; putative | 0.67 ± 0.19 |

| 260 | 1730 | Achn191941 | Tryptophan synthase alpha chain | 0.67 ± 0.04 |

| 261 | 1716 | Achn146961 | Proline iminopeptidase | 0.66 ± 0.11 |

| 262 | 1488 | Achn193791 | Phosphate transporter | 0.66 ± 0.15 |

| 263 | 2102 | Achn042701 | Protein trichome birefringence-like 38 | 0.66 ± 0.02 |

| 264 | 2463 | Achn355751 | Ankyrin repeat-containing protein; putative | 0.66 ± 0.07 |

| 265 | 2378 | Achn053831 | Probable potassium transport system protein kup | 0.66 ± 0.09 |

| 266 | 1455 | Achn141311 | Anthranilate synthase component I; putative | 0.66 ± 0.17 |

| 267 | 1001 | Achn005321 | ER membrane protein complex subunit 8/9 homolog | 0.66 ± 0.13 |

| 268 | 235 | Achn109151 | Inorganic pyrophosphatase protein | 0.65 ± 0.06 |

| 269 | 2039 | Achn327521 | Phosphoenolpyruvate carboxylase; putative | 0.65 ± 0.05 |

| 270 | 397 | Achn123921 | Polyadenylate-binding protein 1 | 0.65 ± 0.13 |

| 271 | 510 | Achn259181 | Putative glutathione S-transferase | 0.65 ± 0.01 |

| 272 | 1002 | Achn339791 | Pentatricopeptide repeat-containing protein | 0.65 ± 0.29 |

| 273 | 1201 | Achn288731 | ATP phosphoribosyltransferase | 0.64 ± 0.12 |

| 274 | 2415 | Achn114051 | Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase | 0.64 ± 0.13 |

| 275 | 1387 | Achn367241 | Citrate synthase | 0.64 ± 0.14 |

| 276 | 2025 | Achn001301 | Putative enoyl-CoA hydratase | 0.64 ± 0.11 |

| 277 | 1598 | Achn340821 | Peptidyl-prolyl cis-trans isomerase | 0.63 ± 0.04 |

| 278 | 97 | Achn387811 | GRAM-containing/ABA-responsive protein | 0.63 ± 0.12 |

| 279 | 53 | Achn091801 | Hydrolase; alpha/beta fold family protein | 0.61 ± 0.03 |

| 280 | 7 | Achn365261 | Putative 3-oxoacyl-(Acyl-carrier protein) reductase | 0.59 ± 0.09 |

| 281 | 509 | Achn136801 | 26S proteasome non-ATPase regulatory subunit | 0.59 ± 0.11 |

| 282 | 743 | Achn334581 | Malate dehydrogenase | 0.58 ± 0.08 |

| 283 | 954 | Achn163691 | Thioredoxin | 0.57 ± 0.17 |

| 284 | 318 | Achn310551 | Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase B | 0.57 ± 0.18 |

| 285 | 1717 | Achn107521 | Kiwellin | 0.56 ± 0.11 |

| 286 | 496 | Achn248641 | 4-nitrophenylphosphatase; putative | 0.55 ± 0.16 |

| 287 | 2016 | Achn130531 | Pyrophosphate-energized proton pump 1 | 0.54 ± 0.17 |

| 288 | 666 | Achn350451 | Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase | 0.53 ± 0.07 |

| 289 | 1539 | Achn361411 | Photosystem I reaction center subunit III | 0.50 ± 0.06 |

| 290 | 2402 | Achn040571 | PRA1 family protein A1 | 0.49 ± 0.08 |

| 291 | 2340 | Achn331061 | Germin-like protein 6 | 0.46 ± 0.08 |

| 292 | 1014 | Achn236041 | Putative Fatty acid oxidation complex subunit alpha | 0.45 ± 0.06 |

A cut-off of a 1.33 fold change in accumulation (B. cinerea inoculation vs. water control) was used to define significance (P < 0.05).

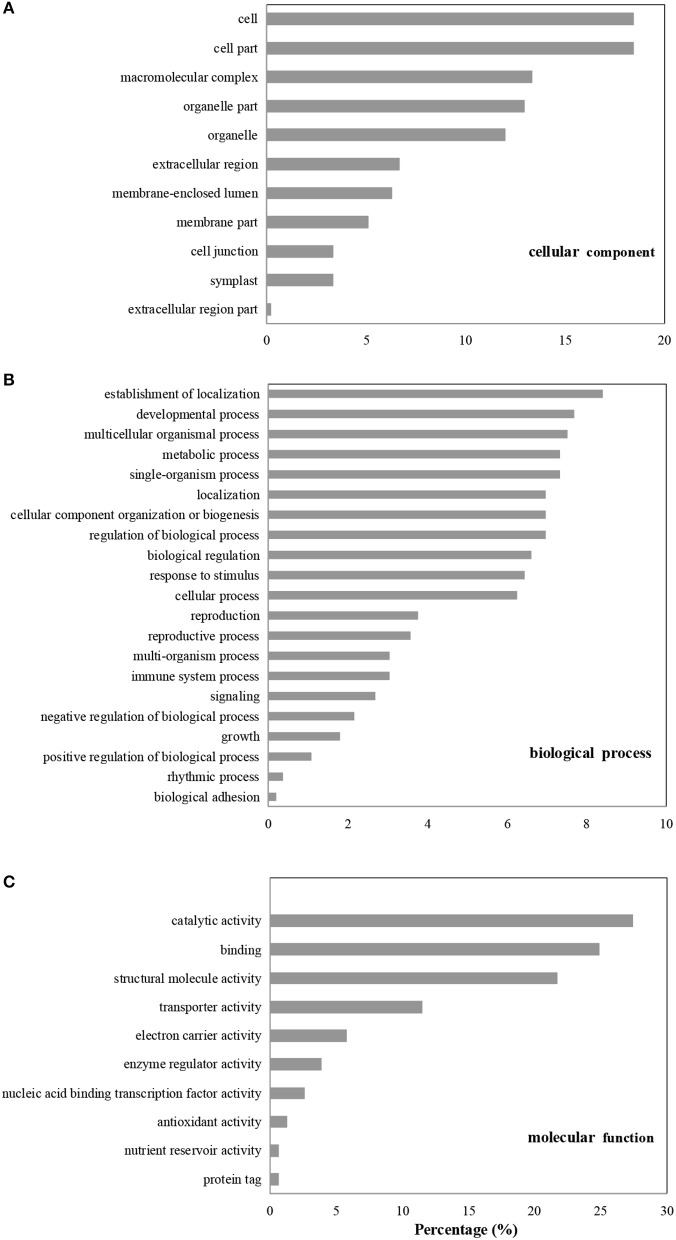

Gene ontology enrichment analysis

A gene ontology (GO) database was used to classify the DAPs that were enriched in the B. cinerea-inoculated vs. the water-inoculated, control kiwifruits. Identified proteins were divided into three groups: cellular component, biological process, and molecular function. In the cellular component category, most of the enriched proteins were related to cell, macromolecular complex, and organelle (Figure 3A). In the biological process category, the most highly enriched proteins were associated with establishment of localization, as well as developmental, multicellular organismal, and metabolic processes. Other processes, such as response to stimulus and signaling, were also affected by B. cinerea infection (Figure 3B). In the molecular function category, the four highly enriched proteins were associated with catalytic activity, binding, structural molecule activity, and transporter activity (Figure 3C).

Figure 3.

GO enrichment analysis of differentially accumulated proteins (DAPs). The DAPs were classified based on cellular component (A), biological process (B), and molecular function (C).

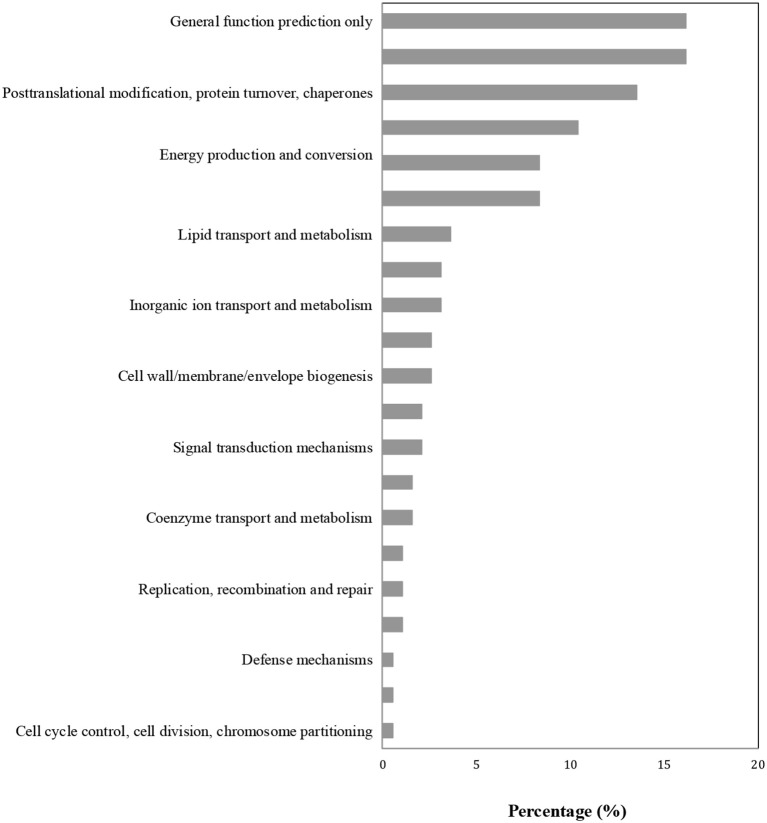

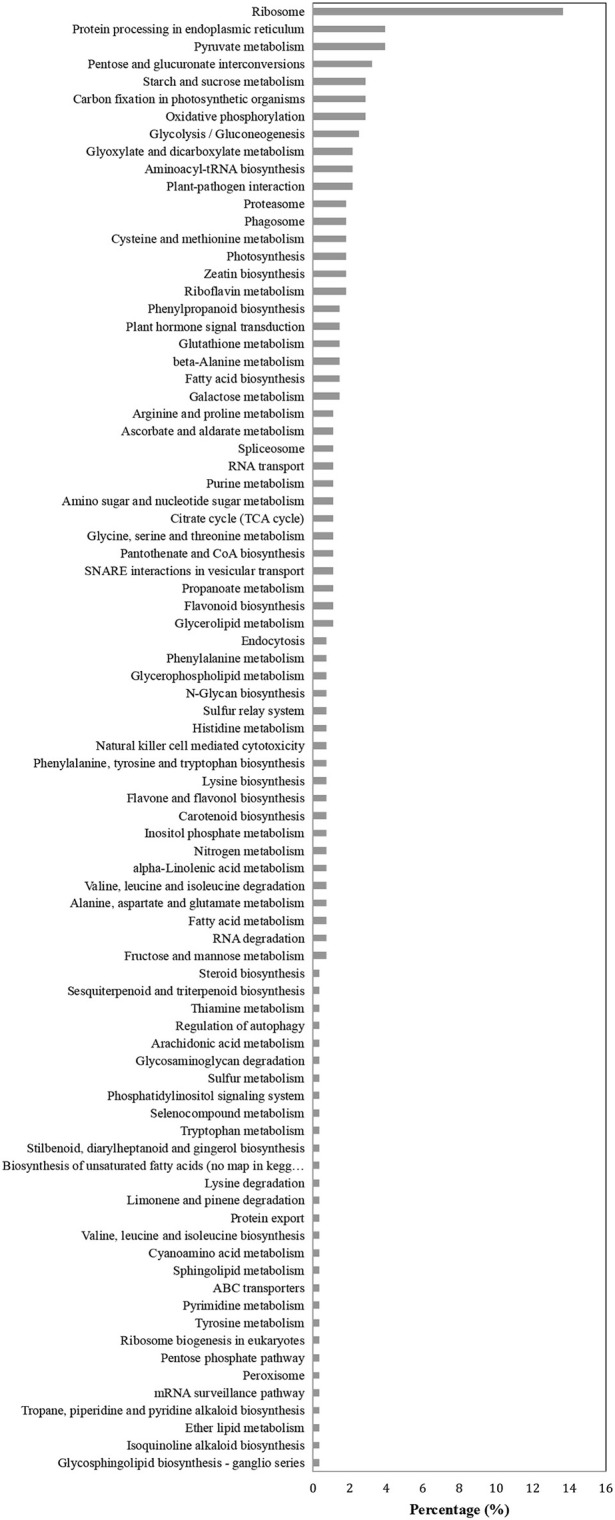

KEGG and COG enrichment analysis

Proteins in the same pathway presumably perform their biological function collectively. Pathway enrichment analysis using the KEGG database was carried out to characterize the potential biological function of the B. cinerea-affected proteins. As shown in Figure 4, the majority of DAPs were associated with metabolism, plant-pathogen interaction, and biosynthesis. The COG classification corresponded well with the results of the KEGG analysis. The majority of DAP proteins were associated with the categories of posttranslational modification, metabolism, signal transduction, and defense mechanisms (Figure 5).

Figure 4.

KEGG pathway enrichment analysis of differentially accumulated proteins (DAPs).

Figure 5.

COG enrichment analysis of differentially accumulated proteins (DAPs).

Penetration site reorganization and polarization

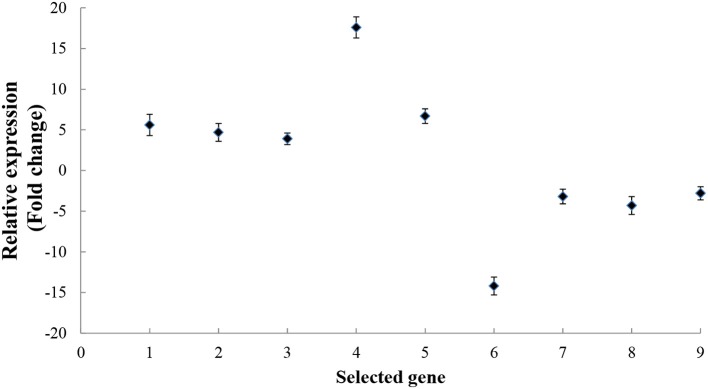

Recognition is the first step in the interaction between a plant host and a pathogen. Using live-cell imaging in Arabidopsis, Yang et al. (2014) determined that the myosin motor protein, Myosin XI, can drive the rapid reorganization and polarization of actin filaments during the infection of Arabidopsis by the barley powdery mildew fungus, Blumeria graminis f. sp. hordei. In the present study, seven kiwifruit Myosin/Myosin-like proteins were identified as responding to B. cinerea. These included: Achn331551, Achn132881, Achn198781, Achn332471, Achn099221, and Achn115381, all of which increased in accumulation (Table 1). The expression pattern of Achn132881 (Myosin 10) was also found to be up-regulated in the analysis of B. cinerea-inoculated kiwifruit by RT-qPCR (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

RT-qPCR analysis of kiwifruit genes encoding proteins that either increased or decreased their level of accumulation in response to B. cinerea. The numbers from 1 to 9 on the x axis represent the following genes in order: Myosin 10 (Achn132881), Pectinesterase (Achn064441), Polygalacturonase-inhibitor protein (Achn126481), Pathogenesis-related Bet v I (Achn053521), Alternative oxidase (Achn228711), Germin-like protein (Achn331061), Annexin (Achn313711), Copper/zinc superoxide dismutase (Achn052701), and Thaumatin (Achn001821). Data presented are the mean ± SD of three independent experiments in which each experiment was comprised of three biological replicates for a total of n = 9.

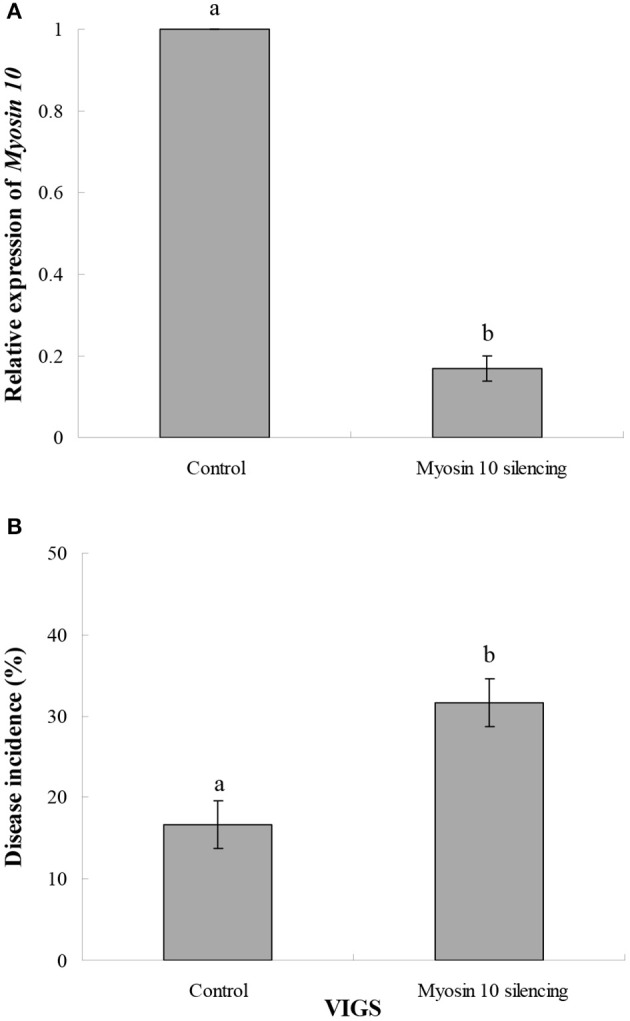

Characterization of Myosin 10 function via VIGS

VIGS was used to characterize the function of Myosin 10 in the infection of kiwifruit by B. cinerea. Results indicated that Myosin 10 was successfully silenced by the VIGS construct (Figure 7A). Furthermore, kiwifruit in which Myosin 10 was silenced were significantly more susceptible to B. cinerea than control kiwifruit based upon the analysis of disease incidence (Figure 7B). These data indicate that Myosin 10 plays a crucial role in the defense response of kiwifruit to B. cinerea.

Figure 7.

(A) Effect of VIGS on the relative expression of Myosin 10 in Myosin 10 VIGS and control kiwifruit inoculated with B. cinerea. (B) Disease incidence (%)in Myosin 10 VIGS and control kiwifruit inoculated with B. cinerea. The control represents kiwifruit without Myosin 10 silencing in which the kiwifruit was inoculated with Agrobacterium carrying an empty vector. Data presented are the mean ± SD of three independent experiments in which each experiment was comprised of three biological replicates for a total of n = 9. Column means with different letters are significantly different according to a Student's t-test at P < 0.05.

Cell-wall degradation or reinforcement

B. cinerea, as a necrotrophic pathogen, initiates infection by synthesizing and secreting plant-cell-wall degrading enzymes (PCWDEs), and then delivering pathogen effectors to host cells, via specialized infection structures, that interfere with host recognition systems (Gourgues et al., 2004). On the host side, kiwifruit may initiate pathogen defense mechanisms that prevent pathogen entrance into host cells and activate other defense responses. Plant cell walls are the first defense barrier, and are rich in pectin, cellulose and hemicellulose. B. cinerea can invade host plants by utilizing these cell wall constituents as a nutrient source. Plants produce various proteinaceous inhibitors in order to protect themselves against microbial pathogen attack. In the present study, two putative polygalacturonase-inhibitor proteins (PGIP), Achn126481, and Achn246321, both of which contain a leucine-rich repeat (LRR), were present at significantly higher levels in inoculated tissues collected at 24 h (early infection stage) after inoculation. PGIPs are well-known to be involved in fungal pathogen resistance. Transgenic tomatoes that express a pear-fruit PGIP were shown to inhibit the growth of B. cinerea in ripe tomatoes (Powell et al., 2000).

The role of pectinesterases, another group of PCWDEs, is more complicated. Four putative pectinesterases, Achn064441, Achn011001, Achn064451, and Achn107321, were present in significantly higher levels in B. cinerea-inoculated kiwifruit at 24 h after inoculation. A proteomic analysis of tomato fruit also found that a putative pectinesterase was activated by B. cinerea, even during the later infection stage (3 days post-inoculation; Shah et al., 2012). Interestingly, one pectinesterase inhibitor protein, Achn317471, decreased in accumulation. Two glycoside hydrolase proteins, Achn106551 and Achn047911, also increased in accumulation. Another two glycoside hydrolase proteins, Achn235831 and Achn367241, however, decreased in accumulation. Overall, the genetic signatures in plant cell-wall-degrading enzymes seem to be affected by or drive the coevolution of plant-pathogen systems (Kubicek et al., 2014). On the one hand, a fungal pathogen needs to activate or increase hydrolase activity in order to facilitate the invasion of host tissues. On the other hand, a host plant needs to be able to inhibit hydrolase activity as a defense mechanism. A similar response pattern was observed for a glucosidase, a plant-cell-remodeling protein. Achn047911 and Achn106551, two predicted alpha-glucosidases, were both shown to accumulate to a greater level (1.37-fold) in pathogen-inoculated kiwifruit than in water-inoculated kiwifruit. In contrast, Achn235831, a predicted beta-glucosidase, exhibited a decreased level of accumulation. A previous study demonstrated that suppressing FaBG3, a strawberry beta-glucosidase gene, resulted in greater resistance to B. cinerea (Li et al., 2013). Lipases also play an important role in plant defense against pathogens in Arabidopsis via negative regulation of auxin signaling (Lee et al., 2009). Results in the present study revealed that Achn230831 and Achn23084, two putative lipase proteins, had lower levels of accumulation in response to B. cinerea. Collectively, these data suggest that they may act as negative regulators of disease resistance in kiwifruit.

Mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) cascades

MAPK cascades are highly conserved signaling modules in eukaryotes that can transduce extracellular stimuli, such as pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) into intracellular responses (Meng and Zhang, 2013). Plant MAPK cascades play important roles in plant defense mechanisms against pathogen attack. MAPK cascades are involved in signaling multiple defense responses, such as the induction of plant defense hormones, ROS generation, defense gene activation, cell wall strengthening, and hypersensitive response (Jalmi and Sinha, 2016; Lee and Back, 2017).

Ras proteins can activate MAPK cascades (Kawano et al., 2010). In our study, Achn389291, a putative Ras-related Rab-2-A protein, had higher levels of accumulation in pathogen-inoculated kiwifruit. Pathogens, however, can utilize effectors to suppress plant MAPK activation and downstream defense responses in order to promote pathogenesis. The level of Achn008501, a predicted small GTPase ADP ribosylation factor, decreased by 0.69-fold in response to B. cinerea infection. This finding is consistent with a previous study (Takác et al., 2013), in which wortmannin, a MAPK (PI3K) inhibitor, decreased the level of the vacuolar trafficking protein RabA1d, a small GTPase that regulates vesicular trafficking in the trans-Golgi network. Another study revealed that a small GTPase ADP ribosylation factor 6 (ARF6) and its effector phospholipase D2 (PLD2) interfere with exosomes by controlling the budding of intraluminal vesicles into multivesicular bodies (MVBs) (Ghossoub et al., 2014). In our study of kiwifruit, Achn061151, a predicted charged MVB protein 4b, exhibited higher levels in response to B. cinerea. Wang et al. (2014) reported that LYST-interacting protein 5 (LIP5) in Arabidopsis could be activated by MPK3 and MPK6 MAPK cascades. LYST-interacting proteins induce the membrane dissociation of endosomal sorting complexes required for transport proteins or MVB synthesis. Further functional studies will be required to elucidate the role of Achn061151 in the response of kiwifruit to B. cinerea.

Ubiquitin-26S proteasome system

The ubiquitin-26S proteasome system (UPS) plays an important role in various signal transduction pathways by controlling the abundance of key regulatory proteins and enzymes. Achn197261 and Achn314841, two predicted proteasome subunit alpha type proteins, exhibited increased levels of accumulation in response to B. cinerea at 24 h post-inoculation. Similar results were reported by Pan et al. (2013), who found that a proteasome subunit alpha type protein was induced in tomato fruit by the necrotrophic fungal pathogen, Rhizopus nigricans, at 48 h post-inoculation. Achn369161 and Achn022881, two predicted proteasome subunit beta type proteins, however, exhibited decreased levels in response to infection. Additionally, Achn136801, a predicted 26S proteasome non-ATPase regulatory subunit, also exhibited a significantly decreased level of accumulation. Thus, the underlying function of these proteins appears to be complex. On one hand, a host plant can potentially defend itself from pathogen attack by activating the UPS to trigger a hypersensitive response, leading to programmed cell death (PCD) at the infection site (Kachroo and Robin, 2013). On the other hand, a pathogen may attempt to suppress immunity-associated PCD or manipulate the host UPS to inhibit host defense proteins and/or enzyme activity (Janjusevic et al., 2006).

Pathogenesis-related (PR) proteins

PR proteins can be grouped into several classes based on the organization of specific amino acid motifs and membrane-spanning domains, two of which are a LRR domain and a START-like domain protein. Results of the present study revealed that two likely LRR proteins, Achn126481 and Achn291371 exhibited increased levels in response to inoculation with B. cinerea. The role of LRR proteins in disease resistance has recently been well documented. In a transcriptomic analysis, LRR genes, such as RGA2 or FEI1, in faba bean (Vicia faba L.) have been reported to be involved in resistance to Ascochyta fabae infection (Ocaña et al., 2015). Park et al. (2012) found that over-expression of rice LRR protein resulted in the activation of a defense response, thereby enhancing resistance to bacterial soft rot in Chinese cabbage, while Wang et al. (2016), using overexpression and gene silencing approaches, reported that the wheat homolog of the nucleotide-binding site-LRR resistance gene, TaRGA, contributed to resistance against powdery mildew (B. graminis). Achn053521, a predicted major latex-like protein that possesses a START-like domain, also increased in accumulation in response to B. cinerea infection in the present study. Gai et al. (2017) reported that when the latex protein HMLX56 from mulberry (Morus multicaulis) was ectopically expressed in Arabidopsis, the transgenic plants showed enhanced resistance to B. cinerea and the bacterial pathogen P. syringae pv. tomato DC3000. Thaumatin-like proteins (TLPs), PR protein family members, can inhibit fungal pathogen growth. Certain TLPs have been found to be associated with stress response, such as the heat shock response (Durand et al., 2012). In the present study, Achn001821, a predicted TLP, exhibited decreased levels in response to B. cinerea at 24 h post-inoculation. In contrast, a TLP in “Amarone” wine grapes was induced by Penicillium expansum in response to water stress (Lorenzini et al., 2016). This finding indicates that DAPs may have different roles in response to abiotic and biotic stresses.

Transcription factors

The heat-shock factor-like transcription factor BF1 functions as a major molecular switch in the transition from plant growth to plant defense (Pajerowska-Mukhtar et al., 2012). Our results identified seven predicted heat shock proteins, Achn092681, Achn089541, Achn001561, Achn079561, Achn383281, Achn011721, and Achn071381, that increased in their accumulation in response to B. cinerea. WD-repeat-domain-related transcription factors have been demonstrated to play an important role in jasmonate (JA) signaling (Qi et al., 2014). JAs are a class of lipid-derived hormones that regulate various defense responses against pathogens and insects (Wasternack and Hause, 2013; Zhang et al., 2017a). Perception of a pathogen or insect invasion induces the synthesis of jasmonoyl-L-isoleucine (JA-Ile), which binds to the COI1-JAZ receptor, triggering the degradation of JAZ repressors and activates transcriptional reprogramming associated with plant defense (Zhang et al., 2017b). In our study, two predicted WD-repeat proteins, Achn228601 and Achn388771, exhibited increased levels of accumulation in response to B. cinerea.

ROS signaling pathway

The ROS signaling pathway plays an important role in plant immunity. Oxidative bursts can trigger pathogen resistance responses (Camejo et al., 2016). Our results indicate that the accumulated level of a predicted glutathione S-transferase, Achn144051, increased in kiwifruit in response to infection by B. cinerea, however, another predicted glutathione S-transferase, Achn259181, decreased. This indicates that various glutathione S-transferases respond differently to the presence of a pathogen. Similar results were observed in grapevine (Vitis vinifera cv. Gamay) cells by Martinez-Esteso et al. (2011). In their comparative proteomic study, two grape peroxidases increased in response to methyl jasmonate, while two decreased. In addition, Achn296481 (a predicted sulfur transferase), Achn147891 (a predicted cysteine desulfurase), Achn052701 (a predicted superoxide dismutase), and Achn285991 (a predicted peroxidase) all exhibited decreased levels of accumulation in response to B. cinerea.

Other proteins

The elemental defense hypothesis assumes that the hyper-accumulation of heavy metals, such as zinc, nickel, or cadmium, in their tissues can protect host plants from pathogen attack. In the present study, a heavy-metal-associated protein, Achn358621, increased in response to B. cinerea. A previous proteomic study in rice reported that enzymes involved in the Calvin cycle and glycolysis decreased in response to infection by the fungus, Cochliobolus miyabeanus (Kim et al., 2014). In our study, the level of seven predicted glycolysis-related proteins, Achn305831, Achn364961, Achn239461, Achn349661, Achn114051, Achn310551, and Achn350451 were also observed to decrease in response to infection. Some unknown proteins, with potential functions based on GO annotation, are worthwhile to be further investigated. For example, Achn277891 involved in abiotic stress response (GO: 0009651) may also participate to the response of kiwifruit to the biotic stress caused by B. cinerea; while Achn095331 involved in oxidation-reduction process (GO: 0055114) may play a role in the ROS signaling pathway.

RT-qPCR analysis

Nine genes coding for proteins that either increased or decreased their level of accumulation in response to B. cinerea in the proteomic analysis were selected for RT-qPCR analysis, in order to determine whether or not the DAPs were also up- or down-regulated at the transcriptional level. Results indicated that the expression level of all nine of the selected genes exhibited a pattern of expression (Figure 6) similar to the pattern of accumulation exhibited by their respective proteins in the proteomic analysis (Table 1).

Conclusions

The present study provides new insight into the interaction that occurs between kiwifruit and B. cinerea during the infection process. A set of DAPs of kiwifruit associated with penetration site reorganization, cell wall degradation, MAPK cascades, ROS signaling, and PR proteins were identified. Using VIGS, Myosin 10 was shown to play a crucial role in modulating resistance to host penetration by B. cinerea. The information from this study may contribute to the development of new approaches and management methods for the effective control of gray mold in kiwifruit.

Author contributions

YS and YoL: conceived and designed the experiments; JL, YoL, and HC: performed the experiments; JL and YiL: analyzed the data; JL, YS, and YoL: drafted the manuscript; YiL: revised the manuscript critically. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by Science and Technology Research Program of Chongqing Education Commission of China (KJ1711275), National Natural Science Foundation of China (31461143008 & 31670688), the Foundation for High-level Talents of Chongqing University of Arts and Sciences (R2016LX01 & R2016TZ02) and Chongqing Key Discipline of Horticulture. The authors thank Dr. Michael Wisniewski from USDA-ARS-Appalachian Fruit Research Station for his helpful comments and critical reading of the manuscript.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpls.2018.00158/full#supplementary-material

A workflow diagram of the iTRAQ-based quantitative proteomic analysis.

Gene-specific primers used in the RT-qPCR analysis.

List of the 2,487 proteins identified by LC-ESI-MS/MS using iTRAQ.

References

- Barnabas L., Ashwin N. M., Kaverinathan K., Trentin A. R., Pivato M., Sundar A. R., et al. (2016). Proteomic analysis of a compatible interaction between sugarcane and Sporisorium scitamineum. Proteomics 16, 1111–1122. 10.1002/pmic.201500245 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Camejo D., Guzmán-Cede-o Á., Moreno A. (2016). Reactive oxygen species, essential molecules, during plant-pathogen interactions. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 103, 10–23. 10.1016/j.plaphy.2016.02.035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen H., Cheng Z., Wisniewski M., Liu Y., Liu J. (2015). Ecofriendly hot water treatment reduces postharvest decay and elicits defense response in kiwifruit. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 22, 15037–15045. 10.1007/s11356-015-4714-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dieryckx C., Gaudin V., Dupuy J. W., Bonneu M., Girard V., Job D. (2015). Beyond plant defense: insights on the potential of salicylic and methylsalicylic acid to contain growth of the phytopathogen Botrytis cinerea. Front. Plant Sci. 6:859. 10.3389/fpls.2015.00859 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durand T. C., Sergeant K., Carpin S., Label P., Morabito D., Hausman J. F., et al. (2012). Screening for changes in leaf and cambial proteome of Populus tremula x P. alba under different heat constraints. J. Plant Physiol. 169, 1698–1718. 10.1016/j.jplph.2012.06.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gai Y. P., Zhao Y. N., Zhao H. N., Yuan C. Z., Yuan S. S., Li S., et al. (2017). The latex protein MLX56 from mulberry (Morus multicaulis) protects plants against insect pests and pathogens. Front. Plan Sci. 8:1475. 10.3389/fpls.2017.01475 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghossoub R., Lembo F., Rubio A., Gaillard C. B., Bouchet J., Vitale N., et al. (2014). Syntenin-ALIX exosome biogenesis and budding into multivesicular bodies are controlled by ARF6 and PLD2. Nat. Commun. 5, 3477. 10.1038/ncomms4477 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- González-Fernández R., Valero-Galván J., Gómez-Gálvez F. J., Jorrín-Novo J. V. (2015). Unraveling the in vitro secretome of the phytopathogen Botrytis cinerea to understand the interaction with its hosts. Front. Plant Sci. 6:839. 10.3389/fpls.2015.00839 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gourgues M., Brunet-Simon A., Lebrun M. H., Levis C. (2004). The tetraspanin BcPls1 is required for appressorium-mediated penetration of Botrytis cinerea into host plant leaves. Mol. Microbiol. 51, 619–629. 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2003.03866.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harren K., Schumacher J., Tudzynski B. (2012). The Ca2+/calcineurin-dependent signaling pathway in the gray mold Botrytis cinerea: the role of calcipressin in modulating calcineurin activity. PLoS ONE 7:e41761. 10.1371/journal.pone.0041761 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imam J., Shukla P., Mandal N. P., Variar M. (2017). Microbial interactions in plants: perspectives and applications of proteomics. Curr. Protein Pept. Sci. 18, 956–965. 10.2174/1389203718666161122103731 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iqbal M. J., Majeed M., Humayun M., Lightfoot D. A., Afzal A. J. (2016). Proteomic profiling and the predicted interactome of host proteins in compatible and incompatible interactions between soybean and Fusarium virguliforme. Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol. 180, 1657–1674. 10.1007/s12010-016-2194-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jalmi S. K., Sinha A. K. (2016). Functional involvement of a mitogen activated protein kinase module, OsMKK3-OsMPK7-OsWRK30 in mediating resistance against Xanthomonas oryzae in rice. Sci. Rep. 6:37974. 10.1038/srep37974 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janjusevic R., Abramovitch R. B., Martin G. B., Stebbins C. E. (2006). A bacterial inhibitor of host programmed cell death defenses is an E3 ubiquitin ligase. Science 311, 222–226. 10.1126/science.1120131 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kachroo A., Robin G. P. (2013). Systemic signaling during plant defense. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 16, 527–533. 10.1016/j.pbi.2013.06.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawano Y., Chen L., Shimamoto K. (2010). The function of Rac small GTPase and associated proteins in rice innate immunity. Rice 3, 112–121. 10.1007/s12284-010-9049-4 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kim J. Y., Wu J., Kwon S. J., Oh H., Lee S. E., Kim S. G., et al. (2014). Proteomics of rice and Cochliobolus miyabeanus fungal interaction: insight into proteins at intracellular and extracellular spaces. Proteomics 14, 2307–2318. 10.1002/pmic.201400066 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kubicek C. P., Starr T. L., Glass N. L. (2014). Plant cell wall-degrading enzymes and their secretion in plant-pathogenic fungi. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 52, 427–451. 10.1146/annurev-phyto-102313-045831 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kulakiotu E. K., Thanassoulopoulos C. C., Sfakiotakis E. M. (2004). Postharvest biological control of Botrytis cinerea on kiwifruit by volatiles of [Isabella] grapes. Phytopathology 94, 1280–1285. 10.1094/PHYTO.2004.94.12.1280 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar Y., Zhang L., Panigrahi P., Dholakia B. B., Dewangan V., Chavan S. G., et al. (2016). Fusarium oxysporum mediates systems metabolic reprogramming of chickpea roots as revealed by a combination of proteomics and metabolomics. Plant Biotechnol. J. 14, 1589–1603. 10.1111/pbi.12522 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee D. S., Kim B. K., Kwon S. J., Jin H. C., Park O. K. (2009). Arabidopsis GDSL lipase 2 plays a role in pathogen defense via negative regulation of auxin signaling. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 379, 1038–1042. 10.1016/j.bbrc.2009.01.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee H. Y., Back K. (2017). Melatonin is required for H2O2- and NO-mediated defense signaling through MAPKKK3 and OXI1 in Arabidopsis thaliana. J. Pineal Res. 62:e12379 10.1111/jpi.12379 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li M., Ma F., Liang D., Li J., Wang Y. (2010). Ascorbate biosynthesis during early fruit development is the main reason for its accumulation in kiwi. PLoS ONE 5:e14281. 10.1371/journal.pone.0014281 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Q., Ji K., Sun Y., Luo H., Wang H., Leng P. (2013). The role of FaBG3 in fruit ripening and B. cinerea fungal infection of strawberry. Plant J. 76, 24–35. 10.1111/tpj.12272 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liñeiro E., Chiva C., Cantoral J. M., Sabido E., Fernández-Acero F. J. (2016). Phosphoproteome analysis of B. cinerea in response to different plant-based elicitors. J. Proteomics 139, 84–94. 10.1016/j.jprot.2016.03.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J., Sui Y., Wisniewski M., Xie Z., Liu Y., You Y., et al. (2017). The impact of the postharvest environment on the viability and virulence of decay fungi. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. [Epub ahead of print]. 10.1080/10408398.2017.1279122 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu L., Liu H., Li S., Zhang X., Zhang M., Zhu N., et al. (2016). Regulation of BZR1 in fruit ripening revealed by iTRAQ proteomics analysis. Sci. Rep. 6, 33635. 10.1038/srep33635 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y., Sun W., Zeng S., Huang W., Liu D., Hu W., et al. (2014). Virus-induced gene silencing in two novel functional plants, Lycium barbarum L. and Lycium ruthenicum. Murr. Sci. Hortic. 170, 267–274. 10.1016/j.scienta.2014.03.023 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lorenzini M., Mainente F., Zapparoli G., Cecconi D., Simonato B. (2016). Post-harvest proteomics of grapes infected by Penicillium during withering to produce Amarone wine. Food Chem. 199, 639–647. 10.1016/j.foodchem.2015.12.032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo J., Tang S., Peng X., Yan X., Zeng X., Li J., et al. (2015). Elucidation of cross-talk and specificity of early response mechanisms to salt and PEG-simulated drought stresses in Brassica napus using comparative proteomic analysis. PLoS ONE 10:e0138974. 10.1145/2818302 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez-Esteso M. J., Sellés-Marchart S., Vera-Urbina J. C., Pedre-o M. A., Bru-Martinez R. (2011). DIGE analysis of proteome changes accompanying large resveratrol production by grapevine (Vitis vinifera cv. Gamay) cell cultures in response to methyl-β-cyclodextrin and methyl jasmonate elicitors. J. Proteomics 74, 1421–1436. 10.1016/j.jprot.2011.02.035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meng X., Zhang S. (2013). MAPK cascades in plant disease resistance signaling. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 51, 245–266. 10.1146/annurev-phyto-082712-102314 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minas I. S., Karaoglanidis G. S., Manganaris G. A., Vasilakakis M. (2010). Effect of ozone application during cold storage of kiwifruit on the development of stem-end rot caused by Botrytis cinerea. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 58, 203–210. 10.1016/j.postharvbio.2010.07.002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nieuwenhuizen N. J., Wang M. Y., Matich A. J., Green S. A., Chen X., Yauk Y. K., et al. (2009). Two terpene synthases are responsible for the major sesquiterpenes emitted from the flowers of kiwifruit (Actinidia deliciosa). J. Exp. Bot. 60, 3203–3219. 10.1093/jxb/erp162 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ocaña S., Seoane P., Bautista R., Palomino C., Claros G. M., Torres A. M., et al. (2015). Large-scale transcriptome analysis in faba bean (Vicia faba L.) under Ascochyta fabae infection. PLoS ONE 10:e0135143. 10.1371/journal.pone.0135143 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pajerowska-Mukhtar K. M., Wang W., Tada Y., Oka N., Tucker C. L., Fonseca J. P., et al. (2012). The HSF-like transcription factor TBF1 is a major molecular switch for plant growth-to-defense transition. Curr. Biol. 22, 103–112. 10.1016/j.cub.2011.12.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan X., Zhu B., Luo Y., Fu D. (2013). Unraveling the protein network of tomato fruit in response to necrotrophic phytopathogenic Rhizopus nigricans. PLoS ONE 8:e73034. 10.1371/annotation/d93695f7-3d30-43f5-b754-ae5cf529ed3d [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park Y. H., Choi C., Park E. M., Kim H. S., Park H. J., Bae S. C., et al. (2012). Over-expression of rice leucine-rich repeat protein results in activation of defense response, thereby enhancing resistance to bacterial soft rot in Chinese cabbage. Plant Cell Rep. 31, 1845–1850. 10.1007/s00299-012-1298-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park Y. S., Im M. H., Gorinstein S. (2015). Shelf life extension and antioxidant activity of ‘Hayward’ kiwi fruit as a result of prestorage conditioning and 1-methylcyclopropene treatment. J. Food Sci. Technol. 52, 2711–2720. 10.1007/s13197-014-1300-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petriccione M., Di Cecco I., Arena S., Scaloni A., Scortichini M. (2013). Proteomic changes in Actinidia chinensis shoots during systemic infection with a pandemic Pseudomonas syringae pv. actinidiae strain. J. Proteomics 78, 461–476. 10.1016/j.jprot.2012.10.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petriccione M., Scaloni A., Di Cecco I., Scaloni A., Scortichini M. (2014). Proteomic analysis of the Actinidia deliciosa leaf apoplast during biotrophic colonization by Pseudomonas syringae pv. actinidiae. J. Proteomics 101, 43–62. 10.1016/j.jprot.2014.01.030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Powell A. L., van Kan J., ten Have A., Visser J., Greve L. C., Bennett A. B., et al. (2000). Transgenic expression of pear PGIP in tomato limits fungal colonization. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 13, 942–950. 10.1094/MPMI.2000.13.9.942 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qi T., Huang H., Wu D., Yan J., Qi Y., Song S., et al. (2014). Arabidopsis DELLA and JAZ proteins bind the WD-repeat/bHLH/MYB complex to modulate gibberellin and jasmonate signaling synergy. Plant Cell 26, 1118–1133. 10.1105/tpc.113.121731 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shah P., Powell A. L. T., Orlando R., Bergmann C., Gutierrez-Sanchez G. (2012). A proteomic analysis of ripening tomato fruit infected by Botrytis cinerea. J. Proteome Res. 11, 2178–2192. 10.1021/pr200965c [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh V., Singh B., Joshi R., Jaju P., Pati P. K. (2017). Changes in the leaf proteome profile of Withania somnifera (L.) dunal in response to Alternaria alternata infection. PLoS ONE 12:e0178924. 10.1371/journal.pone.0178924 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takác T., Pechan T., Samajová O., Samaj J. (2013). Vesicular trafficking and stress response coupled to PI3K inhibition by LY294002 as revealed by proteomic and cell biological analysis. J. Proteome Res. 12, 4435–4448. 10.1021/pr400466x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vizcaino J. A., Csordas A., Del-Toro N., Dianes J. A., Griss J., Lavidas I., et al. (2016). 2016 update of the PRIDE database and its related tools. Nucleic Acids Res. 44, D447–D456. 10.1093/nar/gkw880 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang D., Wang X., Mei Y., Dong H. (2016). The wheat homolog of putative nucleotide-binding site-leucine-rich repeat resistance gene TaRGA contributes to resistance against powdery mildew. Funct. Integr. Genomics 16, 115–126. 10.1007/s10142-015-0471-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang F., Shang Y., Fan B., Yu J. Q., Chen Z. (2014). Arabidopsis LIP5, a positive regulator of multivesicular body biogenesis, is a critical target of pathogen-responsive MAPK cascade in plant basal defense. PLoS Pathog. 10:e1004243. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1004243 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wasternack C., Hause B. (2013). Jasmonates: biosynthesis, perception, signal transduction and action in plant stress response, growth and development. An update to the 2007 review in Annals of Botany. Ann. Bot. 111, 1021–1058. 10.1093/aob/mct067 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiilliamson B., Tudzynski B., Tudzynski P., van Kan J. A. (2007). Botrytis cinerea: the cause of grey mould disease. Mol. Plant Pathol. 8, 561–580. 10.1111/j.1364-3703.2007.00417.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang L., Qin L., Liu G., Peremyslov V. V., Dolja V. V., Wei Y. (2014). Myosins XI modulate host cellular responses and penetration resistance to fungal pathogens. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 111, 13996–14001. 10.1073/pnas.1405292111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang L., Zhang F., Melotto M., Yao J., He S. Y. (2017a). Jasmonate signaling and manipulation by pathogens and insects. J. Exp. Bot. 68, 1371–1385. 10.1093/jxb/erw478 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang M., Cheng S. T., Wang H. Y., Wu J. H., Luo Y. M., Wang Q., et al. (2017b). iTRAQ-based proteomic analysis of defence responses triggered by the necrotrophic pathogen Rhizoctonia solani in cotton. J. Proteomics 152, 226–235. 10.1016/j.jprot.2016.11.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Z., Qin G., Li B., Tian S. (2014). Knocking out Bcsas1 in Botrytis cinerea impacts growth, development, and secretion of extracellular proteins, which decreases virulence. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 27, 590–600. 10.1094/MPMI-10-13-0314-R [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data