Abstract

Several Australian obesity management guidelines have been developed for general practice but, to date, implementation of these guidelines has been shown to be inadequate. In this review, we explore the barriers to obesity treatment and propose a four-stage plan to manage individuals with obesity in general practice using a framework of a multidisciplinary team.

Funding: Novo Nordisk.

Keywords: Australia, Metabolic surgery, Obesity, Obesity management, Obesity pharmacotherapy, Primary care, VLED

Introduction

The prevalence of obesity is rapidly increasing in Australia, from 44% of adults with overweight or obesity in 1989, to 63% in 2012 [1]. In 2013, the National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) released revised guidelines for the management of individuals with overweight and obesity for all primary health care professionals [2]. There are currently no published data indicating the level of pragmatic use of these guidelines in the targeted professional groups. This article does not directly report the results of any trials involving human or animal subjects.

Barriers to Management of Obesity

As general practice is the primary point of contact for most people seeking health services [3], this would seem to be an ideal setting to initiate overweight and obesity management. However, a retrospective analysis of general practice data from Melbourne showed that only 22.2% of adults had their body mass index (BMI) recorded, and only 4.3% had a recorded waist circumference [4]. In addition, the general practitioner (GP) management rate of obesity remained unchanged, at about 0.7 per 100 encounters [5]. A study from the USA showed that, while less than 20% of 2543 individuals with obesity had a documented diagnosis, physicians were more likely to formulate a treatment plan in individuals with a formal diagnosis [6].

Making It Work in General Practice

In this review, we propose a pragmatic, patient-centered and consult-based four-step approach to obesity management in primary care.

An important step in obesity management in primary care should be to increase obesity awareness and upskill GPs on the latest evidence-based effective therapies to overcome physician-based inertia. Such obesity-focused education would allow for the development of pragmatic and structured clinical pathways, taking into account available local resources. The stepwise process below should support clinicians and patients’ making individualized choices of what may effectively assist self-management of obesity and complications.

Step One: Baseline Assessment (Preparatory Consultations 1 and 2)

Identification of Individuals with Obesity

All clinical staff should utilize existing chronic disease management systems to serially record measures of weight, height, waist circumference, and BMI.

BMI is considered the most useful population-level measure of overweight and obesity [7], although known ethnic variations occur [8]. Waist circumference also provides a measure of visceral adiposity (Table 1).

Develop and maintain practice-wide systems focused on patient risk identification.

Table 1.

Definition of disease risk in adults by WHO BMI classification and waist circumference thresholds.

© 2017 WHO, reproduced with permission from http://apps.who.int/bmi/index.jsp?introPage=intro_3.html

| Classification | BMI cutoff points (kg/m2) |

BMI cutoff points for Asian ethnicity (kg/m2) |

Disease risk relative to normal weight for waist circumference cutoff points | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Men: 94–102 cm Women: 80–88 cm |

Men: > 102 cm Women: > 88 cm |

|||

| Normal weight | 18.5–24.9 | 18.5–22.9 | ||

| Overweight | 25.0–29.9 | ≥ 23.0 | Increased | High |

| Obesity class I | 30.0–34.9 | 27.5–32.4 | High | Very high |

| Obesity class II | 35.0–39.9 | 32.5–37.4 | Very high | Very high |

| Obesity class III | ≥ 40.0 | ≥ 37.5 | Extremely high | Extremely high |

Risks of Obesity-Related Complications

Once identified, further assessment of an individual with overweight or obesity may involve:

Engaging individuals at risk: gaining “permission” to discuss obesity and its consequences.

Focused history: evaluation of diet, previous and current physical activity, sleep and psychological assessment.

Physical examination (e.g., cardiovascular measures): apply risk assessment such as the Australian type 2 diabetes risk assessment tool [9] and the Australian absolute cardiovascular disease risk calculator [10].

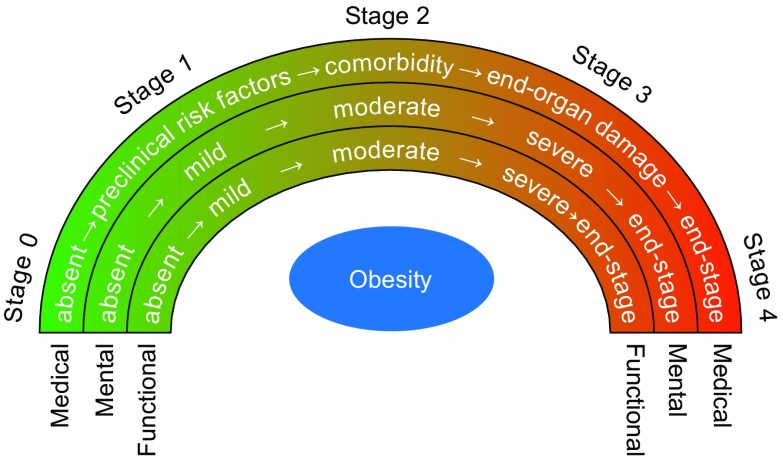

Apply clinical staging of the patient’s condition using clinical tools such as the Edmonton scale [11] (Fig. 1), incorporating anthropometry and obesity complications assessment, to focus management.

Specific focused investigations appropriate for any identified risks or complications.

Medications review: consider suitable alternatives if current medications are known to cause weight gain.

Fig. 1.

The Edmonton scale.

Reproduced with permission from http://www.drsharma.ca

Step Two: Advice, Support, and Therapy (Review Consultations 3 and 4)

- Explore the patient’s understanding of the causes and management of overweight and obesity. Elaborate on the health benefits of weight loss [12].

- Advise that this is a chronic, often progressive, lifelong health condition.

- Collaborate on setting SMART goals [(S)pecific, (M)easurable, (A)ssignable, (R)ealistic, (T)ime-related].

Utilize existing chronic disease management systems including practice staff and nurses, computer databases, and review systems to manage patient support.

Make efforts to individualize treatment for the patient. Focus should be on an improvement in weight-related complications, physical function, cardiovascular fitness, and/or quality of life (Table 2) [13].

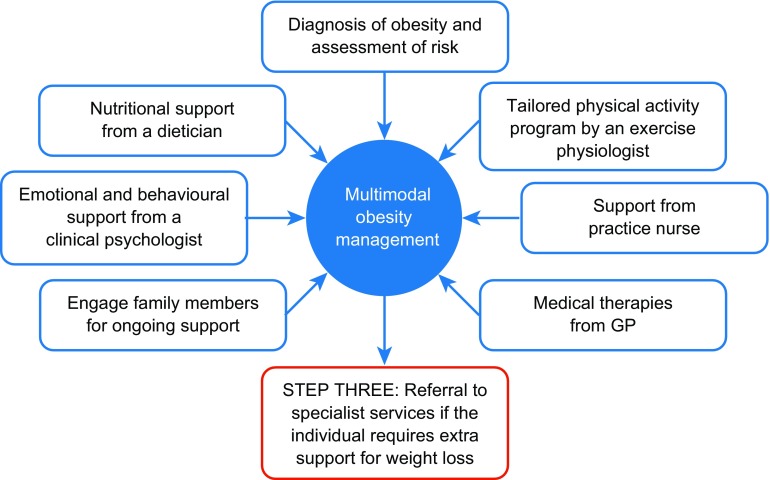

Explain the multimodal team-based management of obesity, including input from external specialists such as an exercise physiologist, dietitian, psychologist, and practice nurse, and how each team member can assist [14]. Team-based members may be assigned according to identified needs (Fig. 2).

Make timely contact (e.g., 2 weeks after commencing assessment) to determine individual engagement, review investigations, and adjust goals if necessary, so that goals can be realistically met.

Discuss economic factors (both patient and local health service provision) that influence treatment choice and availability of team-based resources.

Table 2.

Management of individuals with obesity in Australian primary care [13]

| Obesity needs to be treated with empathy and without prejudice |

| Obesity is associated with increased risks of serious comorbidities |

| Obesity significantly affects quality of life and reduces average life expectancy |

| Effective treatment of obesity should address both the medical and social burden of disease |

| Obesity needs to be treated within the health care system as any other complex disease |

| Obesity management is a lifelong task given that at present no cure exists |

| Calorie reduction, increased physical activity, and other lifestyle modifications are essential foundations upon which other therapies can be built |

| Realistic goals should be set |

| Anti-obesity pharmacotherapy can facilitate weight loss |

| Referral to specialist metabolic obesity services may be appropriate for selected patients |

Fig. 2.

Model for multimodal obesity management

Therapeutic Options

Role of Very-Low-Energy Diets (VLED)

A VLED can be considered as an initial weight-loss strategy, when supervised lifestyle interventions alone have not resulted in sufficient weight loss or comorbidity improvement, or when rapid weight loss is required (e.g., prior to metabolic (previously known as bariatric) or general surgery that is conditional on weight loss) either alone or in combination with pharmacotherapy. A VLED involves three meal replacements equating to less than 3300 kJ/day (800 kcal/day). VLEDs are low in carbohydrates, inducing mild ketosis after 2–3 days, once the body’s glycogen stores have been fully utilized, which subsequently has an anorexic effect.

Role of Pharmacotherapy

The adoption of healthy lifestyle habits is the foundation to managing obesity; however, for many individuals, additional intensive interventions are required. In Australia, three pharmacotherapeutic agents are approved for use in weight management—loss and prevention of regain: phentermine, orlistat, and liraglutide.

Phentermine is a centrally acting adrenergic agonist that suppresses appetite and is approved for use adjunct to dietary management of obesity. Phentermine is registered for use as a short-term therapy, and it is recommended that a review is carried out after 3 months, as long-term safety has not yet been tested. Orlistat—available at higher doses with prescription, or at lower doses over-the-counter—inhibits pancreatic and gastric lipase, reducing fat absorption by approximately 30% [15]. Liraglutide 3.0 mg is a centrally acting glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonist that is available as a once-daily subcutaneous long-term therapy for weight both weight loss and weight maintenance.

As obesity is a long-term chronic disease, health care practitioners should consider the use of long-term medication to both assist with weight loss or to prevent further weight regain. When judging the benefits of pharmacotherapy versus the risks, health care professionals should consider factors including improved control of eating behavior including reduced cravings, quality of life improvements, weight-loss maintenance in addition to weight-loss benefits.

Step Three: Referral Using Treatment Algorithm (Review Consultations 5–8)

-

Either commence supervised lifestyle interventions (including allied health such as psychologists, exercise physiologists, and dietitians) and arrange follow-up visits;

or

Facilitate referral to a specialist team (metabolic obesity clinic and/or metabolic surgery clinic) if:- Patient is unable to achieve > 5% weight loss at 3 months on a lifestyle intervention adjunct to a reduced-energy/low-energy diet, increased physical activity, and/or pharmacotherapy (see “Stopping Rule”).

- Patient is advancing Edmonton stages (in the Edmonton obesity staging system [11]) despite medical therapy intervention.

Prioritize referral of individuals with a BMI ≥ 40 kg/m2 or BMI > 35 kg/m2 with at least one weight-related comorbidity to bariatric surgical services.

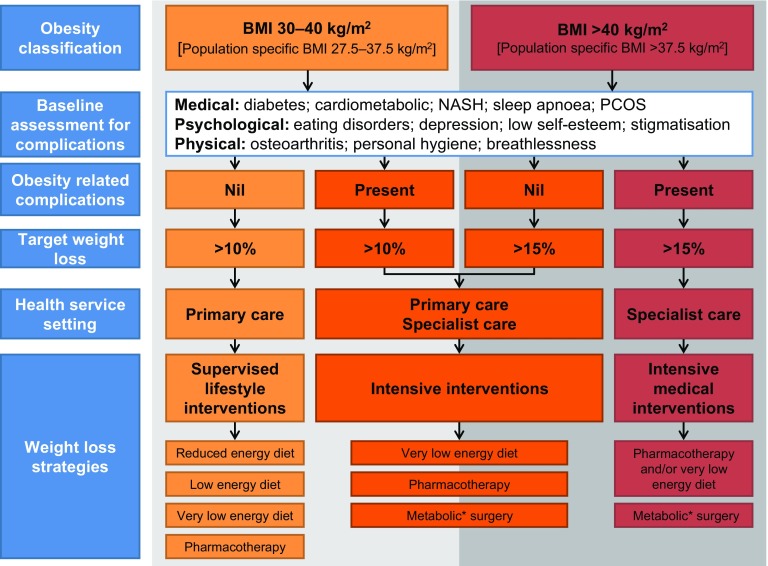

The Australian and New Zealand Obesity Society (ANZOS) has recently published an Australian obesity management algorithm (Fig. 3) developed by a working group with representatives from the Australian Diabetes Society, ANZOS, and the Obesity Surgery Society of Australia & New Zealand [16].

Fig. 3.

The Australian obesity management algorithm

* Previously known as bariatric surgery

© 2016 ANZOS, reproduced with permission from http://anzos.com/assets/Obesity-Management-Algorithm-18.10.2016.pdf

Stopping Rule

Anti-obesity pharmacotherapy should be continued beyond 12 weeks only if at least 5% of initial body weight has been lost since starting medication. Therapy should then be continued for as long as there are clinical benefits, including prevention of significant weight regain. Continuing risks and benefits should be regularly reviewed and discussed [17].

Step Four: Revision and Re-evaluation (Review Consultations 9+)

Prevention of Weight Regain

Consider discussing the use, or reintroduction, of structured intensive programs (including meal replacement, high-protein diets, and anti-obesity pharmacotherapy) shown to improve chances of maintaining weight loss [18].

Individuals need to be educated that the body physiologically defends against weight loss [19]. Help the individual develop an “action plan”, for example, what to do if they regain 3 kg or more [17].

In the Absence of Complications/Comorbidities

If initial weight loss and health improvement goals are achieved, negotiate and create a subsequent plan focusing on strategies for weight maintenance and prevention of weight-related comorbidities [20].

Regularly (e.g., every 8 weeks) monitor and re-evaluate agreed goals including investigations where appropriate.

Co-Existing Complications/Comorbidities and Metabolic Surgery Patients

Re-evaluate weight management goals.

Assess and manage adverse effects of weight loss interventions, or changing/emerging comorbidities (e.g., medication dose adjustment) and individual needs (e.g., pregnancy, ageing, etc.).

Support ongoing communication with, and engagement in, specialist team-based care.

Clinically assess and monitor metabolic and nutritional parameters.

Role of Metabolic Surgery

Metabolic surgery has been shown to be the most effective treatment modality producing a significant and sustainable weight loss (20–35% of starting weight) and provides important benefits for more serious comorbidities [21]. Metabolic surgery should be viewed as a therapeutic tool, and eligible patients need to be carefully selected and supported. Given that, at present, a cure for obesity does not exist, patients will still require lifelong follow-up by both their GP and metabolic surgery clinic. Therefore, GPs should encourage all patients who have had metabolic surgery to be reviewed annually by the surgical team, and more often if clinically indicated. Women are advised to use regular effective contraception and avoid getting pregnant for at least 12 months post-surgery. They should also notify their metabolic surgery clinic prior to considering starting a family or as soon as they find out they are pregnant, for ongoing specialist support.

Weight Loss in the Elderly (≥ 65 Years)

There is a higher risk of obesity-related comorbidities with ageing; however, there is no clear BMI target in this age group. The main goal in older adults with obesity is to improve physical function, balance, and cardiovascular fitness, and minimize both sarcopenia and the impact of obesity-related complications [22]. Use of metabolic surgery as a primary treatment of obesity in older adults (≥ 65 years) is decided on a case-by-case basis.

Final Thoughts

Obesity is a chronic health condition requiring long-term treatment and management. General practitioners have a key role in identifying individuals with or at risk of obesity; implementing appropriate interventions to support weight loss or maintenance; and/or the prevention of weight re-gain. Primary health care practitioners could facilitate patients’ access to obesity support services that can provide the level of treatment required for the psychosocial complexities associated with obesity.

General practices can strategically improve services for these patients and carers through individual GP education, education of practice staff, the development of obesity-focused practice resources (including a referral network of specialist services), and a multidisciplinary team. Ultimately, reducing discrimination will help embed anti-obesity services in our health systems.

Acknowledgements

Funding

Publication charges and open access fees were funded by Novo Nordisk.

Medical writing assistance

Medical writing assistance was provided by Shuna Gould, and editing and submission support was provided by Grant Womack, both of Watermeadow Medical, an Ashfield company. This support was funded by Novo Nordisk.

Authorship

All named authors meet the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) criteria for authorship for this article, take responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole, and have given their approval for this version to be published.

Disclosures

N. Forgione reports non-financial support from Novo Nordisk during the conduct of the study; personal fees from Novo Nordisk, Boehringer Ingelheim, Lilly, MSD, Novartis, Sanofi, Amgen, and Grunbiotics, outside the submitted work. G. Deed reports consultant fees from Novo Nordisk, outside the submitted work, and personal fees from AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Lilly, MSD, Novartis, Sanofi, and Valeant Pharmaceuticals. G. Kilov reports personal fees from Novo Nordisk, outside the submitted work. He has also carried out speaker engagements, and been an advisory board member for Novo Nordisk. G. Rigas reports personal fees from Apollo Endosurgery, personal fees from Dietitians Association of Australia, personal fees from INOVA (a Valeant company), personal fees from Medtronics and personal fees from Novo Nordisk outside the submitted work.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

This article does not directly report the results of any trials involving human or animal subjects.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

Footnotes

Enhanced content

To view enhanced content for this article go to http://www.medengine.com/Redeem/AC1DF06040560C75.

References

- 1.National Health Performance Authority. Overweight and obesity rates across Australia, 2011–12, 2013. http://www.nhpa.gov.au/internet/nhpa/publishing.nsf/Content/Report-Download-HC-Overweight-and-obesity-rates-across-Australia-2011-12/$FILE/NHPA_HC_Report_Overweight_and_Obesity_Report_October_2013.pdf. Accessed Sept 2016.

- 2.National Health and Medical Research Council. Summary guide for the management of oberweight and obesity in primary care Canberra, Australia: National Health and Medical Research Council, 2013. https://www.nhmrc.gov.au/_files_nhmrc/publications/attachments/n57b_obesity_guidelines_summary_guide_131219.pdf. Accessed 12 Dec 2016.

- 3.National Health Performance Authority. Healthy communities: frequent GP attenders and their use of health services in 2012–13. Sydney, Australia: National Health Performance Authority, 2015. http://www.myhealthycommunities.gov.au/Content/publications/downloads/NHPA_HC_Frequent_GP_attenders_Report_March_2015.pdf. Accessed 12 Dec 2016.

- 4.Turner LR, Harris MF, Mazza D. Obesity management in general practice: does current practice match guideline recommendations? Med J Aust. 2015;202(7):370–372. doi: 10.5694/mja14.00998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Britt H, Miller G, Henderson J, et al. A decade of Australian general practice activity 2004–05 to 2013–14. Sydney: Sydney University Press; 2014. p 70.

- 6.Bardia A, Holtan SG, Slezak JM, Thompson WG. Diagnosis of obesity by primary care physicians and impact on obesity management. Mayo Clin Proc. 2007;82(8):927–932. doi: 10.4065/82.8.927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.World Health Organization. Fact Sheet 311: Obesity and overweight Lausanne, Switzerland: World Health Organization, 2016. http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs311/en/. Accessed 12 Dec 2016.

- 8.World Health Organization Appropriate body-mass index for Asian populations and its implications for policy and intervention strategies. Lancet. 2004;363(9403):157–163. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)15268-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Australian Government Department of Health. The Australian type 2 diabetes risk assessment tool, 2010. http://www.health.gov.au/internet/main/publishing.nsf/Content/chronic-diab-prev-aus/$File/austool5.pdf. Accessed 16 Sept 2016.

- 10.National Vascular Disease Prevention Alliance. Australian absolute cardiovascular disease risk calculator, 2012. http://www.cvdcheck.org.au/. Accessed 16 Sept 2016.

- 11.Sharma AM, Kushner RF. A proposed clinical staging system for obesity. Int J Obes (Lond) 2009;33(3):289–295. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2009.2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vidal J. Updated review on the benefits of weight loss. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2002;26(Suppl 4):S25–S28. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0802215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hainer V, Toplak H, Mitrakou A. Treatment modalities of obesity: what fits whom? Diabetes Care. 2008;31(Suppl 2):S269–S277. doi: 10.2337/dc08-s265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yumuk V, Fruhbeck G, Oppert JM, Woodward E, Toplak H. An EASO position statement on multidisciplinary obesity management in adults. Obes Facts. 2014;7(2):96–101. doi: 10.1159/000362191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Guerciolini R. Mode of action of orlistat. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 1997;21(Suppl 3):S12–S23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.ANZOS. The Australian Obesity Management Algorithm: Australian and New Zealand Obesity Society, 2016. http://anzos.com/assets/Obesity-Management-Algorithm-18.10.2016.pdf. Accessed 10 April 2017.

- 17.National Health and Medical Research Council. Clinical practice guidelines for the management of overweight and obesity in adults, adolescents and children in Australia Canberra, Australia: National Health and Medical Research Council, 2013. https://www.nhmrc.gov.au/_files_nhmrc/publications/attachments/n57_obesity_guidelines_140630.pdf. Accessed 12 Dec 2016.

- 18.Johansson K, Neovius M, Hemmingsson E. Effects of anti-obesity drugs, diet, and exercise on weight-loss maintenance after a very-low-calorie diet or low-calorie diet: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Am J Clin Nutr. 2014;99(1):14–23. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.113.070052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sumithran P, Prendergast LA, Delbridge E, et al. Long-term persistence of hormonal adaptations to weight loss. N Engl J Med. 2011;365(17):1597–1604. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1105816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.The Royal Australian College of General Practitioners. Guidelines for preventive activities in general practice. 8th edition Melbourne, Australia: The Royal Australian College of General Practitioners, 2012. http://www.racgp.org.au/download/Documents/Guidelines/Redbook8/redbook8.pdf. Accessed 12 Dec 2016.

- 21.Sjostrom L. Review of the key results from the Swedish Obese Subjects (SOS) trial—a prospective controlled intervention study of bariatric surgery. J Intern Med. 2013;273(3):219–234. doi: 10.1111/joim.12012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Li Z, Heber D. Sarcopenic obesity in the elderly and strategies for weight management. Nutr Rev. 2012;70(1):57–64. doi: 10.1111/j.1753-4887.2011.00453.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]