Abstract

ADP‐dependent glucokinase (ADPGK) is an alternative novel glucose phosphorylating enzyme in a modified glycolysis pathway of hyperthermophilic Archaea. In contrast to classical ATP‐dependent hexokinases, ADPGK utilizes ADP as a phosphoryl group donor. Here, we present a crystal structure of archaeal ADPGK from Methanocaldococcus jannaschii in complex with an inhibitor, 5‐iodotubercidin, d‐glucose, inorganic phosphate, and a magnesium ion. Detailed analysis of the architecture of the active site allowed for confirmation of the previously proposed phosphorylation mechanism and the crucial role of the invariant arginine residue (Arg197). The crystal structure shows how the phosphate ion, while mimicking a β‐phosphate group, is positioned in the proximity of the glucose moiety by arginine and the magnesium ion, thus providing novel insights into the mechanism of catalysis. In addition, we demonstrate that 5‐iodotubercidin inhibits human ADPGK‐dependent T cell activation‐induced reactive oxygen species (ROS) release and downstream gene expression, and as such it may serve as a model compound for further screening for hADPGK‐specific inhibitors.

Keywords: ADP‐dependent glucokinase, glycolysis, 5‐iodotubercidin, kinase inhibitor

Short abstract

PDB Code(s): 5OD2;

Introduction

ADPGKs were first described in hyperthermophilic Archaea where they functionally replace hexokinase (HK) in the glycolytic pathway.1 Similarly to HKs, ADPGKs catalyze glucose phosphorylation to glucose‐6‐phosphate. However, ADPGKs utilize ADP instead of ATP as a phosphate donor. They are distant homologs of family B of sugar kinases within the ribokinase superfamily. To date, several high‐resolution crystal structures of ADPGKs from hyperthermophilic archaea have been determined. Structures of four proteins from closely related species of Thermococci, a class of Euryarchaeota, are available in the Protein Data Bank (PDB IDs: 1GC5, 1L2L, 1UA4, 4B8R).2, 3, 4, 5 Moreover, a crystal structure of archaeal ADP‐dependent phosphofructokinase (ADP‐PFK), a protein closely related to ADPGKs, was also reported.6 Despite the lack of sequence similarity between ADPGK and ATP‐dependent kinases, the structure of ADPGK is very similar to those of ribokinase (PDB:1RKD)7 and adenine kinase (PDB:1BX4).8 Recently, an experimental structure of a N‐terminally truncated variant of murine ADPGK (mADPGK) in the apo form and in complex with AMP (PDB codes 5CCF, 5CK7) has been published.9 Despite little sequence homology (20% identity), the overall fold of mADPGK is similar to that of the archaeal ADPGKs and ADP‐PFKs. In fact, the similarity is so high, that it allowed us to solve the mADPGK structure by molecular replacement using the archaeal protein as a search model.

Regardless of the structural similarities between the ribokinase family and ADPGK, the mechanism of substrate binding is different. The sequence of binding events was described for ribokinases, where interaction with sugar is a prerequisite for nucleotide binding.10 In contrast, ADPGK can bind ADP even in the absence of a sugar molecule.2 Therefore, the precise mechanism of glucose phosphorylation by ADPGK needs further investigation.

The discovery that a human homolog of ADPGK (hADPGK) is involved in the regulation of T cell activation drew attention to ADPGK‐related research.11 A transient increase in hADPGK activity triggered by a T‐cell receptor (TCR) was reported to contribute to T‐cell‐activation‐induced mitochondrial reactive oxygen species (ROS) generation and the resulting downstream gene expression. Moreover, it was demonstrated that ADPGK is preferentially expressed in cells of hematopoietic lineage (i.e., macrophages, monocytes, dendritic cells, T and B cells),11, 12, 13, 14 as well as in various cancers.15, 16, 17

Here, we present the first ADPGK crystal structure from the thermophilic methanogenic archaeon of the class of Methanococci: Methanocaldococcus jannaschii. Our structure reveals the protein in a complex with inhibitor [5‐iodotubercidin (5ITU)], d‐glucose, inorganic phosphate, and a magnesium ion bound at the active site. Moreover, using a model system of T‐cell‐activation‐induced ROS generation and gene expression, we report the inhibitory effect of 5ITU on these phenomena.

Results

The structure of mjADPGK/d‐glucose/5′‐iodotubercidin complex was determined by molecular replacement, using the initial model generated by Automatic Molecular Replacement Pipeline MoRDa.18 The structure was refined to R work/R free values of 0.18/0.22 at 1.98 Å resolution (Table 1). The asymmetric unit consists of three mjADPGK molecules and the unit cell belongs to the P31 space group. Residues 6‐461 (chain A and C) and 4‐461 (chain B), as well as one molecule of the inhibitor, d‐glucose, one Mg2+ ion and inorganic phosphate per protein chain are clearly visible in the electron density.

Table 1.

Data Collection and Refinement Statistics

| Data collection | PDB code: 5OD2 |

|---|---|

| Beamline | BESSY 14.1 |

| Wavelength | 0.9184 |

| Space group | P 31 |

| Unit cell dimensions | |

| a, b, c (Å) | 154.56, 154.56, 50.48 |

| α, β, γ (°) | 90.0, 90.0, 120.0 |

| Resolution (Å) | 47.24–1.98 (2.10–1.98) |

| Observed reflections | 5,47,668 (54,773) |

| Unique reflections | 93,701 (9379) |

| R meas (%) | 18.1 (89.0) |

| Completeness (%) | 99.6 (99.6) |

| I/σI | 8.71 (1.99) |

| Multiplicity | 5.84 |

| Wilson plot B factors (Å2) | 27.12 |

| CC1/2 (%) | 99.5 (64.6) |

| Refinement | |

| Resolution (Å) | 47–1.98 |

| R all (%) | 18.8 |

| R free (%) | 22.4 |

| Rmsd from ideal values | |

| Bond length (Å) | 0.015 |

| Bond angles (°) | 1.739 |

| Avarage B factors (Å2) | 25.17 |

| Ramachandran statistics | |

| Most favored regions (%) | 99.34 |

| Allowed regions (%) | 0.66 |

| Content of asymmetric unit | |

| No. of protein molecules | 3 |

| No. of protein residues/atoms | 1370/11079 |

| No. of solvent atoms | 689 |

| No. of heterogen atoms | 114 |

Values in parentheses are for highest‐resolution shell.

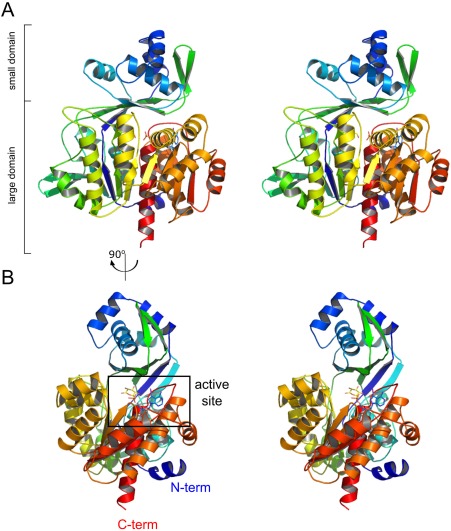

The overall structure of mjADPGK consists of two distinctly distinguished domains, as observed in other ADPGKs (Fig. 1). The large domain, which carries the ADP binding site, is formed by a twisted 10‐stranded β‐sheet flanked by 13 α‐helices and two 310 helices. The smaller domain consists of a curved five‐stranded (β strands 2–4, 8, and 11) β‐sheet with four α‐helical insertions and two additional β strands (9, 10) located at the top of its convex face. The structure reported here represents the enzyme in a closed conformation, in which the two domains approach each other upon binding of glucose and 5‐iodotubercidin.

Figure 1.

The overall structure of mjADPGK. (A) Stereo side view of protein architecture with indication of small and large domains. (B) 5‐iodotubercidin, glucose, and phosphate ion are located at the active site found between small and large domains. Protein is colored from N‐ (blue) to C‐terminus (red).

A similarity search using Dali19 points to Thermococcus litoralis ADP‐dependent glucokinase (tlADPGK, PDB code: 4B8S) as the most similar structure, with rmsd in Cα positions of 2.3 Å over 438 residues at 33% sequence identity (Z factor of 46.2). Our structure presents all the features typical for the ADPGK family; however, significant differences are observed in the loop regions between tlADPGK and mjADPGK. In the latter, loops β11‐α8 and α17‐β17 lack a 310 helix and β‐strand, respectively. Moreover, two β‐strands (9, 10) in the smaller domain form a β‐sheet, which is not present in tlADPGK.

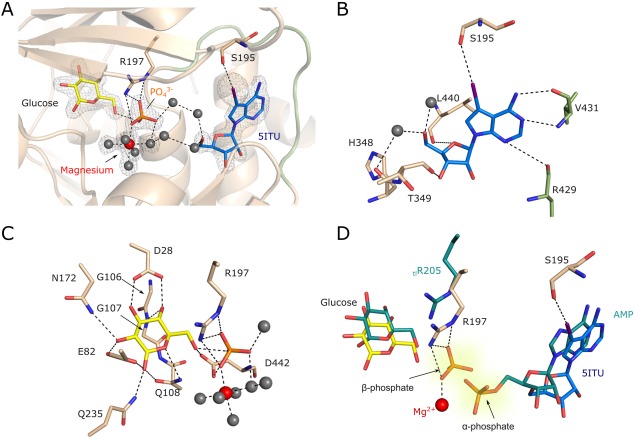

5‐iodotubercidin accommodates the hydrophobic ADP‐binding cleft surrounded by the side chains of mjADPGK residues: Leu440, Ile350, Ala383, and Pro434. Additionally, the compound interacts with the protein by several hydrogen bonds; the adenine moiety N1 and N6 form an H‐bond with Val431 main chain amide and carboxyl, respectively, and the iodine atom is involved in a hydrogen bond interaction with Ser195 [Fig. 2(A,B)]. The ribose moiety is stabilized by a direct hydrogen bond with Thr349 carbonyl oxygen and a network of water molecule‐mediated hydrogen bond interactions with Arg429 amide and His348 carbonyl oxygen.

Figure 2.

The architecture of mjADPGK active site. (A) Close‐up view on mjADPGK active site. 5‐iodotubercidin (blue), inorganic phosphate (orange), magnesium ion (red), and glucose (yellow) are indicated. Most prominent interactions of iodine atom and Ser195 and inorganic phosphate and Arg195 are shown by dashed lines. Water molecules are depicted as grey spheres, nucleotide binding loop is shown as green cartoon. 2Fo‐Fc electron density map contoured at 1σ is shown as grey mesh. (B) Major interactions guiding 5‐iodotubercidin binding. (C) Details of glucose, phosphate, and magnesium binding sites. (D) Superposition of mjADPGK and tlADPGK (PDB:4B8S) active sites. 5ITU, glucose, and side‐chains from M. jannashii are colored in blue, yellow, and wheat respectively. AMP, glucose and Arg205 from T. litoralis ADPGK are colored in teal. Inorganic phosphate from mjADPGK occupies the putative position of ADP β‐phosphate.

Glucose is stabilized by hydrophobic interactions with glycine residues from a conserved GG motif (residues 106–107), as well as within an extensive hydrogen bond network [Fig. 2(C)]. Glucose forms hydrogen bonds with Gly107 amide, and side‐chains of Asp28, Glu82, Asn172, and Glu235. Additionally, the position of the 6OH group is coordinated by hydrogen bonds contributed by the side‐chains of Gln108 and Asp442 as well as by the inorganic phosphate. A ion occupies the putative position of the β‐phosphate of ADP and is stabilized by several hydrogen bonds with Gly441, Gly439, Asp442, and Arg197.

It was suggested previously that a highly‐conserved arginine residue in the ADPGK family (Arg197 in mjADPGK) mediates contacts with the β‐phosphate of ADP to trigger the phosphate transfer reaction.20 In our structure the Arg197 side chain guanidine group interacts with inorganic phosphate via three distinct hydrogen bonds: NH2:O3, NH2:O4, and NE:O4. Furthermore, the magnesium ion displays the common octahedral coordination sphere being coordinated by the phosphate oxygen O3 and five water molecules. The water molecules, in turn, mediate binding to the Phe273 main chain carbonyl oxygen and side chains of Glu272, Glu302, His348, and Asp442.

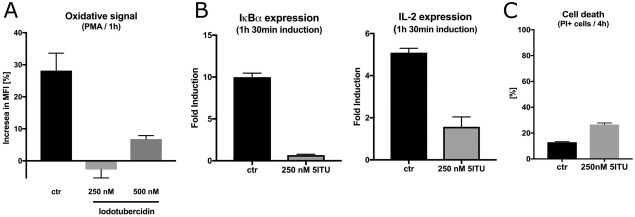

5ITU is commonly regarded as a pan‐kinase inhibitor, with particular efficiency toward adenosine kinase and the nucleoside transporter. It also inhibits other kinases such as ERK2, casein kinases 1 and 2, insulin receptor kinase, phosphorylase kinase, PKA and PKC as well as acetyl‐CoA carboxylase21, 22, 23, 24, 25 and others. Since our data demonstrates 5ITU binding at the active site of ADPGK, we have tested whether 5ITU inhibits ADPGK‐dependent cellular phenomena of T‐cell‐activation‐induced ROS production and downstream gene expression.11 TCR triggering induces transient activation of hADPGK via the diacylglycerol (DAG) branch of the TCR signaling cascade.11 ,reviewed in 14 In turn, a rise in hADPGK activity contributes to downstream mitochondrial ROS production and the ROS‐dependent NF‐κB transcriptional response. To assess effects of 5ITU treatment on these ADPGK‐dependent phenomena, we employed a previously reported model system of human T cell activation based on the treatment of a Jurkat T cell line with the DAG mimic, phorbol 12‐myristate 13‐acetate (PMA) +/‐ Ca2+ ionophore, ionomycin. We demonstrate that 5ITU efficiently blocks PMA‐induced ROS generation as well as ROS/NF‐κB‐dependent expression of IL‐2 and IκBα without induction of significant toxicity (Fig. 3).

Figure 3.

5‐iodotubercidin (5ITU) inhibits T cell activation‐induced ROS generation and subsequent NF‐κB‐dependent gene expression. (A) Jurkat T cells stained with H2DCF‐DA and pre‐treated (30 min) with respective concentrations of 5ITU were activated by phorbol 12‐myristate 13‐acetate (PMA) treatment (1 hr) and the ‘oxidative signal’ was measured by fluorescence‐activated cell sorting (FACS) (mean values +/‐ SD). (B) 5ITU ‐pre‐treated (30 min) Jurkat T cells were activated by PMA/ionomycin for 1 hr. Next, IL‐2 and IκBα gene expression was assayed by RT‐PCR (mean values +/‐ SD). (C) Jurkat T cells were treated with +/‐ 5ITU for 4 hr and cell death was assayed by FACS measeurement of PI+ cells (mean values +/‐ SD).

ADPGK and adenosine kinase (AK) are members of the ribokinase enzyme family of sugar kinases, however, in contrast to ADPGK, AK does not phosphorylate sugar but carries out an ATP‐dependent adenosine phosphorylation. 5ITU was described as an AK inhibitor, and a crystal structure of human AK in complex with 5′‐deoxy‐5‐iodotubercidin (d5ITU) was also reported.26 Despite the fact that both mjADPGK and AK interact with a 5‐iodotubercidine derivative, the inhibitor binding modes for both enzymes are different. In the mjADPGK structure, 5ITU occupies the ADP binding site, whereas, in the case of the AK structure, d5ITU locates in the hydrophobic adenosine binding cleft which in ADPGKs is responsible for interacting with glucose (Supporting Information, Fig. S2). Previous reports have shown that 5ITU inhibits AK with K i = 30 nM27 hence we compared the inhibition kinetics between AK and mjADPGK. Using a glucose‐6‐phosphate dehydrogenase coupled enzymatic assay (Supporting Information) we have found that 5ITU acts as a weak competitive inhibitor of mjADPGK with K i = 0.74 mM that is in the range of K m for ADP (K m = 0.46 mM) (Supporting Information, Fig. S3).

Conclusion

ADPGKs constitute a class of relatively poorly understood glucose phosphorylating enzymes. At the time of their discovery, ADPGKs were thought to play a role in an archaeal‐specific modification of the glycolysis pathway.1 Recently, however, ADPGK was found to drive activation of human T cells.11 This observation opens the possibility of using ADPGK‐specific inhibitors as modulators of immune responses and tools to investigate immunemetabolism.

5‐iodotubercidine was previously described as a potent inhibitor of mitogen‐activated protein kinase, adenosine kinase, casein kinases, protein kinase A, and insulin‐receptor kinase.21, 22, 24, 28 It has been even suggested to be a general protein‐kinase inhibitor.22 Herein, we describe the ADPGK crystal structure from M. jannaschii with 5‐iodotubercidin at the active site (Fig. 2, Supporting Information, Fig. S1). Using this inhibitor in co‐crystallization, we were able to take a snapshot of the phosphoryl transfer process within the ADPGK‐catalyzed reaction, a state where unmodified glucose, a free phosphate, and AMP analog are present at the active site. Unexpectedly, our structure defines the position of an inorganic phosphate ion, which is trapped between d‐glucose and 5‐iodotubercidin. The phosphate ion is stabilized by interactions with magnesium and an invariant Arg197 guanidine group, that was previously proposed to be responsible for the positioning of the β‐phosphate during glucose phosphorylation.29 In fact, superposition of mjADPGK and tlADPGK demonstrated that the inorganic phosphate indeed occupies the β‐phosphate site [Fig. 2(D)]. Moreover, the structure reveals the role of the strictly conserved Asp442 residue, which was proposed to act as a catalytic base activating glucose for the nucleophilic attack.20 Our results show that the aspartic acid side chain interacts via multiple hydrogen bonds with the glucose 6OH group, inorganic phosphate, and a water molecule of magnesium coordination sphere [Fig. 2(C)]. The structure presented in this study further confirms the postulated role of the conserved arginine and aspartic acid residues in catalysis and reveals the previously unknown position of the magnesium ion indispensable for stabilization of the transition state within the phosphate transfer sequence of events.

Using a model of ADPGK‐dependent T‐cell activation, we have demonstrated that 5‐iodotubericin treatment efficiently blocks TCR(PMA/DAG)‐triggered ROS generation and, consequently, NF‐κB‐dependent gene expression (Fig. 3). The strong inhibitory effects of 5ITU on T‐cell‐activation‐induced ROS generation and NF‐κB triggering suggest a pleiotropic mode of action. This assumption is strongly supported by the target promiscuity of 5ITU, mild toxicity (Fig. 3), and a moderate block of T‐cell‐activation‐induced ROS generation and NF‐κB triggering by siRNA or shRNA‐mediated downregulation of ADPGK.11 Nevertheless, 5‐iodotubericine could constitute a suitable starting point for the rational development of ADPGK‐specific inhibitors.

Interestingly, mjADPGK was described as a bifunctional ADP‐dependent glucokinase/phosphofructokinase (ADPGK/PFK) with a reaction rate for the phosphorylation of glucose three times higher than the one for fructose‐6‐phosphate.30 Only recently, a crystal structure of a synthetically designed ADPGK/PFK ancestral protein (AncMT) has been reported providing insight into the evolution of the enzyme specificity toward glucose and fructose‐6‐phosphate.31 Our study complements these findings and presents the first crystal structure of a bifunctional ADPGK/ADP‐PFK.

Materials and Methods

Molecular cloning and expression

Gene encoding full‐length mjADPGK (Uniprot: Q58999, residues 4‐462) was optimized for E. coli expression system, synthesized (Genescript) and cloned without expression/purification tag into pET24d plasmid using NcoI/BamHI restriction sites. E. coli BL21 (DE3) competent cells were transformed with pET24d‐mjADPGK plasmid and grown in Terrific Broth (Bioshop) at 37°C until OD600 = 1.3. Expression was induced by addition of 0.5 mM final concentration of isopropyl β‐d‐1‐thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) and continued for 12 hr at 18°C. Cells were harvested by centrifugation at 4000g. Pellets were flash‐frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80°C until purification.

mjADPGK purification

Frozen pellets were thawed, resuspended in lysis buffer (20 mM Hepes, 350 mM NaCl, 10 mM MgCl2, 2.5% glycerol, pH = 8.0) and lysed by sonication. The lysate was cleared by centrifugation (50,000g for 20 min at 4°C). The supernatant was precipitated by addition of polyethyleneimine (Sigma) up to 0.5% (v/v). The denatured proteins and nucleic acids were removed by centrifugation (50,000g, 20 min). The clear supernatant was heat‐shocked at 90°C for 10 min and clarified (50,000g, 20 min). The supernatant containing mjADPGK was dialyzed against low ionic strength binding buffer A (20 mM Hepes, pH = 8.0, 20 mM NaCl, 5 mM MgCl2) and the protein was purified using ion‐exchange chromatography (Mono Q, GE Healthcare) in the binding buffer A. The NaCl elution fractions containing mjADPGK were pooled and further purified by size‐exclusion chromatography (Superdex 75, GE Healthcare) in GFB buffer (20 mM Hepes, 150 mM NaCl, 5 mM MgCl2). The fractions containing mjADPGK were pooled, concentrated and directly used for crystallization.

Crystallization and structure determination

mjADPGK was concentrated to 10 mg/mL and crystalized using siting drop vapor diffusion method. 2 μL drops of protein solution containing 5‐iodotubercidin (5‐iodo‐7‐β‐d‐ribofuranosyl‐7H‐pyrrolo[2,3‐d]pyrimidin‐4‐amine, 2 mM) glucose (5 mM), Hepes (20 mM), sodium chloride (150 mM), and magnesium chloride (5 mM) were mixed with an equal volume of the reservoir solution containing sodium chloride (0.2 M) BIS‐Tris (0.1 M pH = 5.5) and polyethylene glycol 3350 (25% w/v). Crystals were grown at 20°C and appeared after 3–5 days.

Crystals for data collection were soaked in the reservoir solution supplemented with glycerol (20%) as a cryoprotectant and then flash‐frozen in liquid nitrogen. Diffraction data were collected on BL14.1 beamline operated by the Helmholtz‐Zentrum Berlin (HZB) at the BESSY II electron storage ring (Berlin‐Adlershof, Germany).32 All data were indexed, integrated scaled and merged using XDS package33 with XDSAPP2.0 graphical user interface.34 Molecular Replacement was performed in MoRda18 and Phaser35, 36 using the large domain of ADP‐dependent phosphofructokinase from Pyrococcus horikoshii OT3 (PDB:3DRW) as a search model. Structures were refined using Refmac537 within ccp4 package.36 Model building and completion were performed with Coot.38, 39 Structure coordinates were deposited in Protein Data Bank with the accession code 5OD2.

Determination of ROS generation, changes in gene expression, and cell death

Jurkat T cells (clone E6‐1, human acute T cell leukemia cell line) were obtained from ATCC and cultured at standard conditions in RPMI medium supplemented with 10% FBS, 1 mM glutamine and penicillin–streptomycin (10 U/mL). All chemicals were from Sigma‐Aldrich unless stated otherwise. Cells were stained with H2DCF‐DA (Life Technologies, 5 μM) for 30 min (+/‐5‐iodotubericin), stimulated with phorbol 12‐myristate 13‐acetate (PMA) (10 ng/mL, 1 hr) without inhibitor removal, washed with ice‐cold PBS and analyzed by Fluorescence‐Activated Cell Sorting (FACS). Generation of the “oxidative signal” was calculated as described previously.11, 14

To analyze activation‐induced gene expression, Jurkat T cells were pre‐treated +/‐ 5‐iodotubericin for 30 min and activated with PMA (10 ng/mL) and ionomycin (1 μM) for 1 hr in the presence/absence of the inhibitor. Total cellular RNA was isolated with RNAeasy mini kit (Qiagen) and reverse‐transcribed. Gene expression was analyzed by SybrGreen monitored RT‐PCR with IL‐2 and IκBα specific primers. The measurements were normalized to actin transcript level. Conditions of reverse‐transcription, RT‐PCR, and primer sequences were identical to those reported previously.11, 14

Cell death was measured by propidium iodide (PI) exclusion method. Cells were stained with PI solution (4 μg/mL in PBS) for 30 min and PI+ cells were assayed by FACS.

Author Contribution

PG initiated the project, designed experiments, collected X‐ray data and solved the structure, PT purified and crystalized mjADPGK, and performed enzymatic assay, MW refined the structure, GD provided key reagents, MMK designed and performed cell biology experiments, MW, MMK, GD and PG analyzed the data, MW, MMK, GD and PG wrote the final manuscript. All authors commented on the manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest regarding the publication of this article.

Supporting information

Supporting Information

Acknowledgments

Authors thank HZB for the allocation of synchrotron radiation beamtime. Faculty of Biochemistry, Biophysics and Biotechnology of Jagiellonian University is a partner of the Leading National Research Center (KNOW) supported by the Ministry of Science and Higher Education. We also thank Ban Judek and Jonathan Heddle for the final manuscript editing.

Broader Statement: The article reports the first structure of ADP‐dependent glucokinase (ADPGK) from Methanocaldococcus jannaschii in a complex with a pan‐kinase inhibitor 5‐iodotubercidin. Presented data confirm the previously proposed glucose phosphorylation mechanism and the role of the conserved arginine residue in this process. Moreover, since human ADPGK is involved in the regulation of T cell activation, the study lays the foundation for the future development of ADPGK‐specific inhibitors to be used in immunology research.

References

- 1. Kengen SW, Tuininga JE, de Bok FA, Stams AJ, de Vos WM (1995) Purification and characterization of a novel ADP‐dependent glucokinase from the hyperthermophilic archaeon Pyrococcus furiosus . J Biol Chem 270:30453–30457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Ito S, Fushinobu S, Yoshioka I, Koga S, Matsuzawa H, Wakagi T (2001) Structural basis for the ADP‐specificity of a novel glucokinase from a hyperthermophilic archaeon. Structure 9:205–214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Tsuge H, Sakuraba H, Kobe T, Kujime A, Katunuma N, Ohshima T (2002) Crystal structure of the ADP‐dependent glucokinase from Pyrococcus horikoshii at 2.0‐A resolution: a large conformational change in ADP‐dependent glucokinase. Protein Sci 11:2456–2463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Ito S, Fushinobu S, Jeong JJ, Yoshioka I, Koga S, Shoun H, Wakagi T (2003) Crystal structure of an ADP‐dependent glucokinase from Pyrococcus furiosus: implications for a sugar‐induced conformational change in ADP‐dependent kinase. J Mol Biol 331:871–883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Rivas‐Pardo JA, Herrera‐Morande A, Castro‐Fernandez V, Fernandez FJ, Vega MC, Guixé V (2013) Crystal structure, SAXS and kinetic mechanism of hyperthermophilic ADP‐dependent glucokinase from Thermococcus litoralis reveal a conserved mechanism for catalysis. PLoS One 8:e66687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Currie MA, Merino F, Skarina T, Wong AH, Singer A, Brown G, Savchenko A, Caniuguir A, Guixe V, Yakunin AF, Jia Z (2009) ADP‐dependent 6‐phosphofructokinase from Pyrococcus horikoshii OT3: structure determination and biochemical characterization of PH1645. J Biol Chem 284:22664–22671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Sigrell JA, Cameron AD, Jones TA, Mowbray SL (1998) Structure of Escherichia coli ribokinase in complex with ribose and dinucleotide determined to 1.8 A resolution: insights into a new family of kinase structures. Structure 6:183–193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Mathews II, Erion MD, Ealick SE (1998) Structure of human adenosine kinase at 1.5 A resolution. Biochemistry 37:15607–15620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Richter JP, Goroncy AK, Ronimus RS, Sutherland‐Smith AJ (2016) The structural and functional characterization of mammalian ADP‐dependent glucokinase. J Biol Chem 291:3694–3704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Sigrell JA, Cameron AD, Mowbray SL (1999) Induced fit on sugar binding activates ribokinase. J Mol Biol 290:1009–1018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Kamiński MM, Sauer SW, Kamiński M, Opp S, Ruppert T, Grigaravičius P, Grudnik P, Gröne H‐J, Krammer PH, Gülow K (2012) T cell activation is driven by an ADP‐dependent glucokinase linking enhanced glycolysis with mitochondrial reactive oxygen species generation. Cell Rep 2:1300–1315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Hruz T, Laule O, Szabo G, Wessendorp F, Bleuler S, Oertle L, Widmayer P, Gruissem W, Zimmermann P (2008) Genevestigator v3: a reference expression database for the meta‐analysis of transcriptomes. Adv Bioinformatics 2008:420747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Wu C, Orozco C, Boyer J, Leglise M, Goodale J, Batalov S, Hodge CL, Haase J, Janes J, Huss JW, 3rd , Su AI (2009) BioGPS: an extensible and customizable portal for querying and organizing gene annotation resources. Genome Biol 10:R130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kamiński MM, Röth D, Krammer PH, Gülow K (2013) Mitochondria as oxidative signaling organelles in T‐cell activation: physiological role and pathological implications. Arch Immunol Ther Exp (Warsz) 61:367–384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Richter S, Richter JP, Mehta SY, Gribble AM, Sutherland‐Smith AJ, Stowell KM, Print CG, Ronimus RS, Wilson WR (2012) Expression and role in glycolysis of human ADP‐dependent glucokinase. Mol Cell Biochem 364:131–145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Wu D, Sunkel B, Chen Z, Liu X, Ye Z, Li Q, Grenade C, Ke J, Zhang C, Chen H, Nephew KP, Huang TH, Liu Z, Jin VX, Wang Q (2014) Three‐tiered role of the pioneer factor GATA2 in promoting androgen‐dependent gene expression in prostate cancer. Nucleic Acids Res 42:3607–3622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Lee KE, Spata M, Bayne LJ, Buza EL, Durham AC, Allman D, Vonderheide RH, Simon MC (2016) Hif1a deletion reveals pro‐neoplastic function of B cells in pancreatic neoplasia. Cancer Discov 6:256–269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Vagin A, Lebedev A (2015) MoRDa, an automatic molecular replacement pipeline. Acta Cryst A 71:s19. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Holm L, Rosenstrom P (2010) Dali server: conservation mapping in 3D. Nucleic Acids Res 38:W545–W549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Guixe V, Merino F (2009) The ADP‐dependent sugar kinase family: kinetic and evolutionary aspects. IUBMB Life 61:753–761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Fluckiger‐Isler RE, Walter P (1993) Stimulation of rat liver glycogen synthesis by the adenosine kinase inhibitor 5‐iodotubercidin. Biochem J 292:85–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Massillon D, Stalmans W, van de Werve G, Bollen M (1994) Identification of the glycogenic compound 5‐iodotubercidin as a general protein kinase inhibitor. Biochem J 299:123–128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Parkinson FE, Geiger JD (1996) Effects of iodotubercidin on adenosine kinase activity and nucleoside transport in DDT1 MF‐2 smooth muscle cells. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 277:1397–1401. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Fox T, Coll JT, Xie X, Ford PJ, Germann UA, Porter MD, Pazhanisamy S, Fleming MA, Galullo V, Su MS, Wilson KP (1998) A single amino acid substitution makes ERK2 susceptible to pyridinyl imidazole inhibitors of p38 MAP kinase. Protein Sci 7:2249–2255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Garcia‐Villafranca J, Castro J (2002) Effects of 5‐iodotubercidin on hepatic fatty acid metabolism mediated by the inhibition of acetyl‐CoA carboxylase. Biochem Pharmacol 63:1997–2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Muchmore SW, Smith RA, Stewart AO, Cowart MD, Gomtsyan A, Matulenko MA, Yu H, Severin JM, Bhagwat SS, Lee CH, Kowaluk EA, Jarvis MF, Jakob CL (2006) Crystal structures of human adenosine kinase inhibitor complexes reveal two distinct binding modes. J Med Chem 49:6726–6731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Cottam HB, Wasson DB, Shih HC, Raychaudhuri A, Di Pasquale G, Carson DA (1993) New adenosine kinase inhibitors with oral antiinflammatory activity: synthesis and biological evaluation. J Med Chem 36:3424–3430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Ugarkar BG, DaRe JM, Kopcho JJ, Browne CE, 3rd , Schanzer JM, Wiesner JB, Erion MD (2000) Adenosine kinase inhibitors. 1. Synthesis, enzyme inhibition, and antiseizure activity of 5‐iodotubercidin analogues. J Med Chem 43:2883–2893. : [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Merino F, Guixe V (2008) Specificity evolution of the ADP‐dependent sugar kinase family: in silico studies of the glucokinase/phosphofructokinase bifunctional enzyme from Methanocaldococcus jannaschii . FEBS J 275:4033–4044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Sakuraba H, Goda S, Ohshima T (2004) Unique sugar metabolism and novel enzymes of hyperthermophilic archaea. Chem Rec 3:281–287. : [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Castro‐Fernandez V, Herrera‐Morande A, Zamora R, Merino F, Gonzalez‐Ordenes F, Padilla‐Salinas F, Pereira HM, Brandão‐Neto J, Garratt RC, Guixe V (2017) Reconstructed ancestral enzymes reveal that negative selection drove the evolution of substrate specificity in ADP‐dependent kinases. J Biol Chem 292:15598–15610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Mueller U, Darowski N, Fuchs MR, Forster R, Hellmig M, Paithankar KS, Puhringer S, Steffien M, Zocher G, Weiss MS (2012) Facilities for macromolecular crystallography at the Helmholtz‐Zentrum Berlin. J Synchrotron Radiat 19:442–449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Kabsch W (2010) Xds. Acta Cryst 66:125–132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Sparta KM, Krug M, Heinemann U, Mueller U, Weiss MS (2016) XDSAPP2.0. J Appl Cryst 49:1085–1092. [Google Scholar]

- 35. McCoy AJ, Grosse‐Kunstleve RW, Adams PD, Winn MD, Storoni LC, Read RJ (2007) Phaser crystallographic software. J Appl Cryst 40:658–674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Winn MD, Ballard CC, Cowtan KD, Dodson EJ, Emsley P, Evans PR, Keegan RM, Krissinel EB, Leslie AG, McCoy A, McNicholas SJ, Murshudov GN, Pannu NS, Potterton EA, Powell HR, Read RJ, Vagin A, Wilson KS (2011) Overview of the CCP4 suite and current developments. Acta Cryst 67:235–242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Murshudov GN, Vagin AA, Dodson EJ (1997) Refinement of macromolecular structures by the maximum‐likelihood method. Acta Cryst 53:240–255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Emsley P, Cowtan K (2004) Coot: model‐building tools for molecular graphics. Acta Cryst 60:2126–2132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Emsley P, Lohkamp B, Scott WG, Cowtan K (2010) Features and development of Coot. Acta Cryst 66:486–501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supporting Information