Abstract

Prosystemin, originally isolated from Lycopersicon esculentum, is a tomato pro‐hormone of 200 aminoacid residues which releases a bioactive peptide of 18 aminoacids called Systemin. This signaling peptide is involved in the activation of defense genes in solanaceous plants in response to herbivore feeding damage. Using biochemical, biophysical and bioinformatics approaches we characterized Prosystemin, showing that it is an intrinsically disordered protein possessing a few secondary structure elements within the sequence. Plant treatment with recombinant Prosystemin promotes early and late plant defense genes, which limit the development and survival of Spodoptera littoralis larvae fed with treated plants.

Keywords: Prosystemin, natively unfolded, solanaceae, Spodoptera littoralis, plant defense

Introduction

Plants, as sessile organisms, cannot escape adverse environmental changes and have developed very efficient defense responses against stress agents. The molecular mechanisms underlying defense responses against insect attack are activated locally, at the damaged site, and promote a long‐distance signaling largely modulated by jasmonic acid (JA).1 The pioneering work on tomato plants showed how wound damage results both in local and systemic expression of proteinase inhibitors (PIs), disrupting the digestion of feeding insects.2, 3 In tomato, these events are triggered by a peptide hormone named Systemin (Sys).4 The signaling molecule is an octadecapeptide intensely investigated over the years5, 6, 7, 8, 9 which, upon wounding, is released from the C‐terminal region of a larger pro‐hormone of 200 amino acids called Prosystemin (Prosys) by means of a molecular mechanism still unknown.8

Prosys gene is transcribed at low level in physiological conditions, while its expression is enhanced by mechanical wounding or feeding by herbivore insects.6, 10 The key role of Prosys in plant defense was discovered by Ryan's group through the analysis of transgenic tomato plants expressing the coding gene in sense and anti‐sense orientation. The overexpression of Prosys was associated with the constitutive production of PIs connected with a significant increase of resistance against herbivore insects.6, 10, 11 Conversely, plants expressing Prosys cDNA in anti‐sense orientation showed a nearly complete suppression of PIs production upon wounding12 associated with a reduced capacity to limit the feeding damage by Manduca sexta larvae.13 The constitutive production of Prosys in tomato plants resulted in an increased resistance not only against chewing larvae but also against phytopathogenic fungi and aphids.9, 14, 15 Moreover, transgenic plants showed indirect defenses reinforced, being more attractive towards parasitoids and predators of their insect pests16, 17 and show an increased plant resistance to saline stress.18 Finally, it was recently demonstrated that the pro‐hormone, deprived of the Sys aminoacidic sequence, promotes defense responses which are not induced by the release of Sys peptide.19

The observation that Prosys elicits multiple defense pathways to protect tomato plants against a wide range of stress agents suggests that it may play a role in plant defense broader than expected. Due to the lack of structural information on the whole Sys precursor, we performed a structural and biological characterization of it. The gathered experimental evidence on the full length recombinant protein, along with predictions by bioinformatics analysis, proved that Prosys is a member of the Intrinsically Disordered Proteins (IDPs) family. IDPs are a class of proteins completely or only partially unstructured but still functionally active.20 These results suggest novel hints for the understanding of the multiple roles of Prosys in the tomato defense mechanisms.

Results

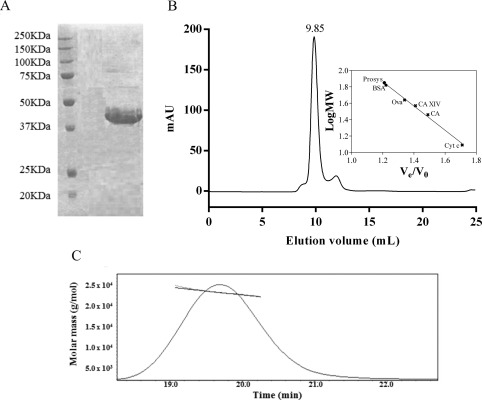

Recombinant Prosys has an hydrodynamic dimension typical of intrinsically disordered proteins

Prosys has no sequence similarity with any structurally characterized protein. To investigate its structure‐function features, pETM11‐Prosys was produced in E. coli BL21(DE3) bacterial strain by expressing a PCR‐amplified cDNA in NcoI/XhoI sites. Prosys, recovered from the soluble part of lysate, was purified at a high degree (above 98%) upon three purification steps with a final yield of 4 mg/L colture. As assessed by SDS‐PAGE, Prosys showed an aberrant migration with an apparent molecular mass of 40 kDa, exceeding the expected molecular mass of 26 kDa (inclusive of the His‐tag) [(Fig. 1(A)] and its identity was confirmed only by LC‐ESI‐MS analysis (data not shown). Elution from the SEC column occurred as a sharp peak with an apparent molecular mass (MMapp) of about 71 kDa [Fig. 1(B)], as estimated by the calibration curve [inset Fig. 1(B)]. This value was well above the expected value (MMtheo) and was not compatible with a monomeric globular structure. Indeed, the elution volume suggested either a folded trimeric oligomerization or a flexible conformation with scarce compactness. By means of light scattering studies, the hydrodynamic properties of Prosys were elucidated, showing that, in solution, the prohormone occurs as a monomeric protein, with a molecular mass of 23.7 ± 0.1 kDa [Fig. 1(C)], and an apparent hydrodynamic radius of 5.61 ± 0.01 nm of the monodisperse peak, which is indicative of a protein with low compactness. The same measurements, carried out in presence of urea, showed an increase of the hydrodynamic radius to 8.6 ± 3.3 nm, suggesting that the protein in native conditions contains a residual structural content which is lost in presence of a denaturing agent.21

Figure 1.

Recombinant Prosys has an hydrodynamic dimension typical of intrinsically disordered proteins. (A) 15% SDS‐PAGE stained with Coomassie Brilliant Blue. Molecular masses of broad range protein marker (20–250 kDa) (BIORAD) are indicated in kDa. (B) Elution profile of Prosys on a Superdex 75 10/16 size exclusion chromatography column. Inset, molecular mass deduced from the calibration curve. (C) molecular mass value of Prosys determined by light scattering analysis.

Protease sensitivity

A poorly compact protein is more sensitive to protease activity as cleavage sites are better exposed than in globular structures. Then, to further corroborate the low compactness of the recombinant protein, Prosys was subjected to proteolytic digestion using a protease with a broad substrate specificity such as trypsin.22 Prosys, incubated with different E:S ratio and at different time intervals, was readily digested already after 1 h of incubation (Fig. S1). In contrast, a well‐folded and structured protein, such as carbonic anhydrase II, was not digested after 24 h incubation time (data not shown).

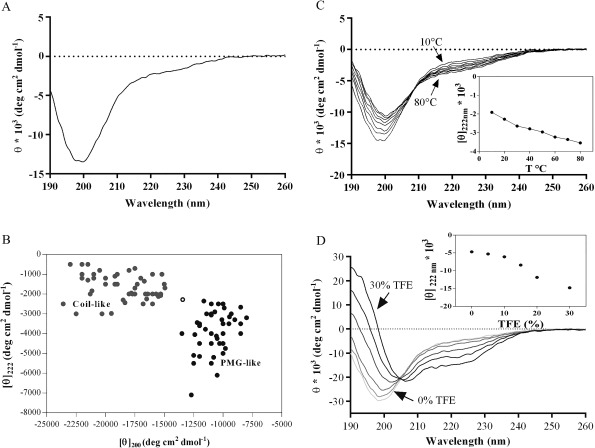

CD spectra of Prosys and temperature effects

The secondary structure content was investigated by far UV‐CD spectroscopy [Fig. 2(A)]; Prosys spectrum at neutral pH showed low ellipticity at 190 nm and a large negative ellipticity at 198 nm, typically observed for proteins in a largely disordered conformation. Some residual secondary structure was consistent with the observed ellipticity values at 200 and 222 nm.21, 23, 24 Indeed, according to Uversky, extended disordered proteins can be assigned to two structurally different groups, premolten globule‐like (PMG‐like) group and random coil‐like (RC‐like) group, depending on the ratio of the ellipticity values at 200 and 222 nm.25 Notably, Prosys falls in the twilight zone between RC‐like and PMG‐like, suggesting that it exhibits some amount of residual secondary structure [Fig. 2(B)]. This result is in accordance with DLS data, which showed the presence of residual intramolecular interactions in native conditions, a behavior shared by proteins having a PMG‐like conformation.21 Prosys undergoes temperature‐induced changes; as the temperature increases, modest but discernible far‐UV CD spectral changes are evident, due to the formation of secondary structure [Fig. 2(C)]. The structural changes induced by heating are completely reversible and are not driven by a cooperative behavior [inset Fig. 2(C)]. Heat‐induced structuring is a typical feature of IDPs, in contrast to globular proteins, which undergo unfolding upon heating.26 The peculiar effect is likely due to the increased strength of the hydrophobic interactions occurring at high temperature, which act as a driving force for hydrophobic folding.23, 26

Figure 2.

Far‐UV CD spectra of Prosys. (A) CD spectrum was recorded in 10 mM phosphate buffer, pH 7.4 at a protein concentration of 4 µM. (B) [θ]222 versus [θ]200 ellipticity plot modified from Uversky;25 [θ]222 of a set of well‐characterized coil‐like (gray circles) and premolten globule‐like subclasses (black circles) has been plotted against [θ]200. The position of Prosys is indicated with an empty circle. (C) Temperature effect on folding of Prosys (at 10°C, 20°C, 30°C, 40°C, 50°C, 60°C, 70°C, and 80°C). The ellipticity [θ]222 versus temperature is shown in the inset. (D) TFE induced folding of Prosys (at 0%, 5%, 10%, 15%, 20%, and 30%). The ellipticity [θ]222 versus TFE percentage is shown in the inset.

Induced folding of Prosys

We tested the propensity of Prosys to fold in water/trifluoroethanol (TFE) mixtures. TFE as a cosolvent is often used as a probe to investigate hidden structural propensities of proteins and peptides,27 since it can mimic a more hydrophobic environment which occurs during protein‐protein interactions.28 Thus, in order to evaluate the potential folding of Prosys upon partner binding, CD spectra were recorded at increasing concentrations of TFE. Prosys showed an increased α‐helical content upon addition of TFE, as indicated by the characteristic maximum at 190 nm and the occurrence of a double minima at 208 and 222 nm [Fig. 2(D)]. A slow increase of α‐helical content gradually occurred from 5 to 15% TFE, whereas most of the unstructured‐to‐structured transitions arose between 20% and 30% TFE, reaching a plateau at higher concentrations. It is worth noting that the existence of an isodichroic point at 204 nm is consistent with a two‐state coil‐helix transition.21, 29

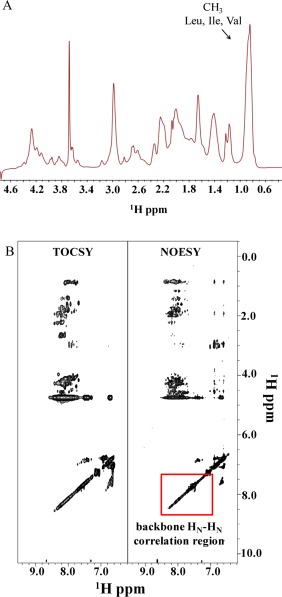

Conformational analysis by NMR spectroscopy

Conformational analysis of Prosys in solution was further conducted by means of 1D [1H] and 2D [1H, 1H] NMR spectroscopy. The 1D [1H] NMR spectrum together with the 2D [1H, 1H] TOCSY and 2D [1H, 1H] NOESY experiments of Prosys presented the canonical features of the unstructured proteins, being dominated by a poor spectral dispersion, typical of IDPs. In 1D [1H] spectrum, a strong methyl peak in the random coil range around 0.85 ppm, that arises from the 18 isoleucines, 6 leucines, and 11 valines contained in Prosys, could be observed [Fig. 3(A)]. This evidence highlights the absence in Prosys of the canonical hydrophobic core of a folded system that would have generated upfield‐shifts for the resonances of these methyl protons. Similarly, as can be easily seen in 2D [1H, 1H] TOCSY and NOESY spectra [Fig. 3(B)], the backbone amide protons fall in a rather narrow chemical shift range, that is, 7.7–8.4 ppm; the absence of backbone amide HN resonances around 9 ppm and of Hα protons provided with chemical shifts around 5–6 ppm [Fig. 3(B)], let us to speculate the absence of extended β‐structures in the protein. In general, the lack of HN–HN NOE connectivities between amide protons [Fig. 3(B)] further confirms the absence of ordered secondary structure elements in a relevant amount.

Figure 3.

Conformational analysis by NMR spectroscopy. (A) Expansion of the 1D [1H] NMR spectrum of Prosys containing signals from backbone Hα and side chain protons. The strong methyl peak generated by Leu, Ile, and Val residues is highlighted. (B) Comparison of 2D [1H, 1H] TOCSY and NOESY spectra of Prosys. Panels show the spectral regions where peaks from HN and aromatic protons can be seen. 1D and 2D NMR spectra were acquired with a 2 mg/mL protein sample at 298 K on a 600 MHz spectrometer equipped with a cold probe (see Experimental Section for further details).

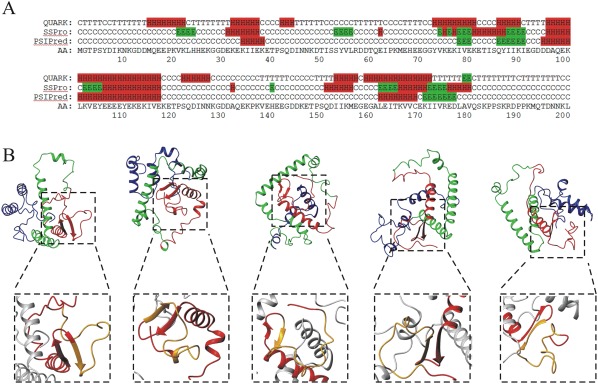

In silico analysis of Prosys

Prosys has a unique amino acid sequence, rich of charged residues. This peculiarity was already underlined in previous papers together with the observation of repetitive sequence elements.30 However, an in‐depth sequence analysis aiming at studying the sequence‐structure relationship of Prosys is lacking. For this reason, we performed a bioinformatics analysis of Prosys primary sequence using a wide range of in silico tools. We used first Composition Profiler, which allows to identify statistically significant patterns of amino acid enrichment or depletion along the sequence.31 To this aim, the sequence composition of Prosys was compared to that of proteins within the Swiss‐Prot database.21 Prosys showed a peculiar amino acid composition, depleted in the so‐called “order promoting” residues, that include Cys, Asn, Leu, Val,Trp, Phe, and Tyr which are regularly represented in the hydrophobic core of folded globular proteins.20 On the contrary, it is enriched in most “disorder promoting” residues such as Gln, Asp, Glu, Lys and Pro [Fig. 4(A)]. These sequence features suggested that Prosys behaves as an intrinsically disordered protein. Notably, the abundance of charged residues (Asp, Glu, and Lys) and the lack of hydrophobic residues (Trp, Phe), or their scarceness (Tyr), are indicative of a high net charge and low mean hydrophobicity, respectively. When correlating these two parameters32 Prosys is predicted to be a disordered protein [Fig. 4(B)].

Figure 4.

Sequence properties of Prosys. (A) Amino acid compositional analysis performed by means of Composition Profiler tool. Prosys sequence is compared to the reference value of the average amino acid frequencies of the Swiss‐Prot database.31 (B) Charge‐Hydrophobicity plot generated as described by Uversky.25 Black dots, intrinsically disordered protein reported in literature (data partially taken from Ref. 26), black triangles, natively folded proteins randomly taken from PDB. Solid black line, border between the ID and the natively folded proteins, described by the equation H = (R + 1.151)/2.785, where H and R are the mean hydrophobicity and the mean net charge, respectively. Empty red circle, Prosys. (C) Predictions of intrinsic disorder by PONDR‐fit (red line) and DisMETA (blue line) predictors. Values higher than 0.5 indicate a propensity for disorder, and lower than 0.5 indicate a propensity for order.

In addition, since previously discussed experimental data provide evidence that Prosys is a PMG‐like protein not completely unfolded, but with a certain degree of compactness and a residual secondary structure (Fig. 2), we used in silico tools to obtain further insights into its structural features. To this aim we performed disorder predictions and calculations of its secondary and tertiary structure. PONDR‐FIT33 and DisMeta34 predictors were employed to assess the degree of disorder in the sequence. Results suggest that Prosys is mainly disordered [Fig. 4(C)] with local propensities to order, as indicated by the disorder score close or below 0.5 [Fig. 4(C)] in regions 75–105 and 160–180 which belong to the Central and the C‐terminal part of Prosys, respectively.

Secondary structure calculations were performed using different predictors: PSIPRED,35 SSPro,36 and QUARK.37 Results shown in Figure 5(A) indicate that most of the sequence is random coil with local tendencies to assume a regular secondary structure (α‐helix or β‐strand), mainly in the Central and C‐terminal region of the protein, consistently with the above discussed disorder predictions [Fig. 4(C)].

Figure 5.

Structure predictions of Prosys. (A) Secondary structure predictions by QUARK, SSPro and PSIPred. The amino acid (AA) sequence is also shown. H: helix, E: strand, C: coil, T: turn. (B) Ribbon representation of five out of the 10 3D‐structure models predicted by QUARK ab initio server for Prosys full‐length (the entire ensemble of 10 models is reported in Figure S1). N‐terminal region (1–70) is in blue; Central region (71–140) is in green; C‐terminal region (140–200) is in red. Details of beta‐hairpin (172–180) which precedes the Sys polypeptide in the C‐terminal region (140–200) of Prosys in each model have been highlighted in dashed boxes. Region corresponding to Sys polypeptide is in orange.

Finally, we carried out predictions of the three‐dimensional structure of Prosys using QUARK ab initio server37 [Fig. 5(B), S2]. The models generated by QUARK have a quite low TM‐score value (TM‐score = 3.1), which indicates no single‐high probability model for a specific fold but an ensemble of energetically similar conformations. This finding further suggested that Prosys is an IDP, devoid of a unique well defined global fold, possessing long disordered regions. Moreover, the analysis of the structural models provided insights into the local propensity of protein regions to assume a regular secondary structure, as expected for a PMG‐like protein. In details, in all the models we found that: (i) the N‐terminal region [blue ribbon in Fig. 5(B)] is highly disordered, having long random coil segments; (ii) the central part of the protein [green ribbon in Fig. 5(B)] consists of two long V‐shaped α‐helices with a varying inter‐helices angle; (iii) the C‐terminal region [red ribbon in Fig. 5(B)] displays a long random coil segment and an α‐helix/β‐hairpin motif which precedes the disordered Sys region. According to the QUARK models [Fig. 5(B)], these three regions can be reciprocally oriented in many different ways, leading to an ensemble of possible conformations.

Notably, there is a good agreement between the different in silico predictors used, indicating that Prosys is mainly unstructured and possesses some residual secondary structure elements in the Central and C‐terminal region of the protein.

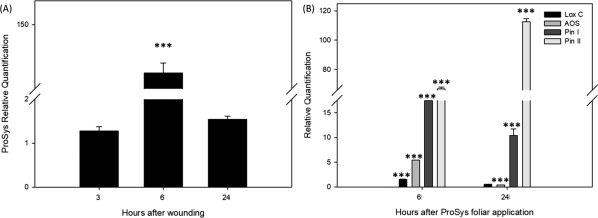

Recombinant Prosys activates the expression of tomato defense genes

The biological activity of Prosys was monitored by evaluating the expression of defense‐related gene in response to the application of purified recombinant pro‐hormone on wounded leaves. Four defense related genes were selected: two early genes of the octadecanoid pathway, that lead to the formation of JA, Lipoxygenase (Lox C) and Allene oxide synthase (AOS), and two late JA related defense genes, encoding for proteinase inhibitors I and II (Pin I and Pin II, respectively). In order to circumvent the effect of endogenous Prosys on the activation of defense genes following wounding, we experimentally identified the time point for its exogenous application. To this aim, a wounding experiment was carried out as previously described (see experimental procedures), in which leaves of wealthy tomato plants were wounded and endogenous Prosys transcripts quantified through qRT‐PCR, 3, 6, and 24 h after wounding. As shown in Figure 6(A), the expression of the endogenous Prosys largely decreased 24 h after wounding. Therefore, we selected this time point for leaf treatments with the recombinant protein and quantified, by qRT‐PCR, the transcripts of Lox, Aos, Pin I and Pin II, at 6 and 24 h after treatment. Relative quantification data were calibrated on controls represented by wounded leaves treated with PBS. As shown in Figure 6(B) all genes resulted significantly overexpressed (min P value 3.26E−18, max p value 1.2E−9) following the exogenous Prosys application, indicating that recombinant Prosys is biologically active.

Figure 6.

Expression analysis of Prosys and Prosys related genes by RT‐PCR. (A) ProSys relative quantification 3, 6, and 24 h after wounding. Data are calibrated on unwounded samples. (B) Relative quantification of early (LoxC and AOS) and late (Pin I and Pin II) defense genes in plants treated with 100 pM Prosys as indicated in the text. Data are calibrated on controls treated with PBS after wounding. Asterisks indicate data statistical significance (T‐test; *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001). Error bars indicate standard error.

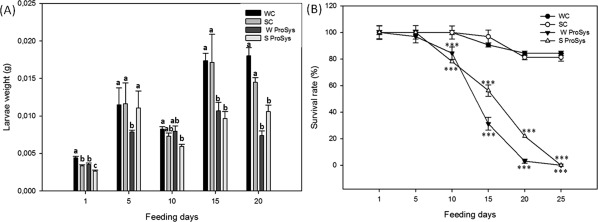

Leaf treatment with recombinant Prosys strongly counteracts larval growth and survival

Since Prosys overexpression is associated with plant resistance to insects,9 we investigated if the exogenous application of the recombinant pro‐hormone could mimic the overexpression of the endogenous gene. For this purpose we monitored growth and survival of S. littoralis larvae fed with treated or untreated leaves. Larvae fed with Prosys treated leaves had a significant reduction of their weight (18 mg for WC and 7 mg for W Prosys at the 15th feeding day, P < 0.0001, Tukey‐Kramer HSD test) and showed a significantly reduced survival rate compared with larvae fed with untreated leaves used as control (90.6% for WC control, 31.25% W Prosys at the 15th feeding day, P < 0.0001 Log‐rank test) (Fig. 7). In order to evaluate if the treatment of the plant with Prosys was able to induce a systemic defense response in untreated leaves of the same plant, the same feeding bioassay was carried out with distal leaves. A similar significant reduction of weight increase (14 mg for SC and 10 mg for S Prosys at the 15th feeding day, P < 0.0001, Tukey‐Kramer HSD test) and survival (96.8% for systemic control SC and 56.25% for S Prosys, at the 15th feeding day, P < 0.0001 Log‐rank test) was observed (Fig. 7). Taken together, these results confirmed that recombinant Prosys is biologically active and that its exogenous application is associated with resistance against herbivore insects, as observed with transgenic plants overexpressing the natural pro‐hormone.9

Figure 7.

Weight increase and survival rates of S. littoralis larvae fed with untreated or treated leaves. WC, wounded leaves used as control; SC, leaves distal from wounded leaf used as systemic control; W Prosys, wounded leaves treated with ProSys; S Prosys, leaves distal from the Prosys treated leaf. (A) Weights registered for treated samples were compared to controls by One‐Way ANOVA followed by the Tukey–Kramer Honestly Significant Difference (HSD) multiple range test (P < 0.05). Letters indicate different statistical groups. (B) Survival percentages of tests and controls were compared by One‐Way ANOVA coupled with Log‐Rank test. Asterisks indicate data statistical significance (One‐Way ANOVA and Longrank test; ***P < 0.001).

Discussion

The present study provides a multidisciplinary characterization of plant pro‐hormone Prosys. The pro‐hormone, which does not contain N‐linked glycosylation sites, was produced as bacterial recombinant protein, overcoming the expression problems encountered in earlier studies.38 Indeed, previous attempts of bacterial expression of the full‐length pro‐hormone were poorly efficient, basically due to the presence of a translation start site (Shine‐Dalgarno sequence) just upstream an internal ATG codon.38 This sequence, which provides a common bacterial start site, likely directed the translation of a truncated form (Prosys 185) missing the first 14 initial amino‐acids. In addition, an intramolecular association of the ribosome binding site of the pET 11d expression vector with the 5′’ coding region of the pro‐hormone contributed to the low production of the recombinant protein. These problems were only partially overcome by producing a mutated protein (Met15Ala) and by introducing conservative mutations in the 5′ coding region of the Prosys nucleotide sequence.38 Here we show that the use of pETM11 vector allows the expression of the full‐length protein in E. coli with an His tag at the N‐ter part of the protein. The protein has a unique amino acid composition with a considerable number of acidic residues (20 Asp and 35 Glu over 200 amino acid) which are responsible for an aberrant migration on SDS‐PAGE21, 39 [Fig. 1(A)]. Accordingly, the apparent molecular mass of Prosys was 1.5 times higher than that calculated from sequence data or measured by mass spectrometry [Fig. 1(B)]. The high protease‐sensitivity, the DLS results and the analysis of the 1D [1H] NMR spectrum confirmed the lack of a packed core within the protein. On the basis of CD spectra, Prosys is characterized by a largely disordered conformation, with a residual secondary structure content which increases upon heating. 1D and 2D NMR spectra exhibited low chemical shift dispersion that is distinctive of IDPs and revealed, in agreement with CD spectroscopy, that Prosys is mostly unstructured. All together, these data indicate that Prosys belongs to the IDP family, having residual secondary structure which is characteristic of PMG‐like proteins. In silico results further corroborated the gathered experimental evidence showing that Prosys is a disordered protein containing few regular structural elements in the Central (sequence 75–110) and C‐terminal region (sequence 160–180). IDPs are a very large class of proteins lacking a stable or ordered three‐dimensional structure which play a central role in regulation of signaling pathways and in crucial cellular processes, including regulation of transcription, and translation.40 Their flexibility allows them to assume a wide spectrum of states from fully unstructured to partially structured. Specific recognition may occur by binding plasticity, which allows IDPs to interact promiscuously with different macromolecular partners.20, 39 When binding to a partner, IDPs may undergo a conformational transition known as induced folding. In order to investigate the eventual induced folding of Prosys we performed CD analysis in presence of TFE thus mimicking the mainly hydrophobic environment sensed in a protein‐protein interaction. CD results show that the protein gains an ordered three‐dimensional structure following TFE addition, exhibiting α‐helices formation. This leads to hypothesize that a large part of Prosys consists of intrinsically disordered regions (IDRs), which may undergo a disorder‐to‐order transition upon binding with a partner.25, 41

Interestingly, the in silico study predicts the presence of a β‐hairpin motif which precedes the disordered Sys sequence at the carboxy‐terminal end of Prosys [Fig. 5(B)]. It is tempting to speculate that this structural motif could represent a recognition site for hormone‐releasing enzymes responsible for the cleavage and release of Sys. This is a fascinating hypothesis to be tested since, to date, very little is known about the molecular mechanism of Sys release from the precursor.

Finally, plant assays revealed that the recombinant pro‐hormone is biologically active being very effective in the induction of tomato defense‐related genes, which confer protection against S. littoralis larvae both locally and systemically. This evidence further corroborated that the observed intrinsic disorder of recombinant protein is a functional innate feature of Prosys and is not due to experimental conditions. The registered biological activity is likely due to the release of the Sys peptide from the precursor.8 Although little information on the mechanism of Sys release from the precursor is available,42 it has been suggested that, upon environmental cues such as insect attacks, the prohormone is processed and the released peptide initiates a signal transduction pathway that leads to the induction of PIs and other defense‐related genes.6 The observed biological activity is worth of consideration from an applied perspective, since it nicely substantiates the use of recombinant proteins and synthetic peptides as innovative tools in insect control, which act not by exerting a toxic action but by triggering plant defense responses.

Many regulatory proteins involved in signal transduction and transcription regulation belong to the IDP family,40, 43 which has been mainly investigated in the animal kingdom,44, 45, 46 rather than in plants.47 In the latter case, IDPs have a broad impact on many biological functions, being involved mainly in plant responses to abiotic stress, transcription regulation, plant immunity, light perception and development.48, 49 As plants are sessile organisms they have to constantly respond to the perturbations occurring in the environment. This phenotypic plasticity is supported also by a wide diversity of defense strategies that plants select in response to the environmental cues based on an efficient coordination of various signaling networks. Consequently, protein disorder can play an extremely important role in plant defense, providing a fast mechanism to obtain complex, interconnected and versatile molecular networks. For example, LEA (Late Embryogenesis Abundant) are a group of entirely or partially disordered proteins that coordinate different signals and pathways involved in the plant molecular response to abiotic stresses.50 These multiple functions appear to be strictly correlated with the IDP nature of LEA that work as a hub interacting with multiple partners.48 Similarly, the disordered nature of Prosys may promote selective binding of several partners as well as integrate signals from multiple stress agents9 supporting the hypothesis that Prosys has a biological function other than being an intermediate in the synthesis of Sys. Interestingly, as reported for genes encoding IDPs or disordered domains that originated by duplication and module exchange,51 Prosys gene is thought to be originated through duplication and elongation events.30

In conclusion, the detailed characterization of Prosys by means of a multidisciplinary approach reveals that this precursor is an intrinsically disordered protein, suggesting new interesting insights on the role of IDPs into plant response against biotic stressors. Considering that protein‐protein interactions mediated by disordered regions are involved in molecular recognition and signaling events, it is proposed that Prosys may exert its multifaceted biological activity as a consequence of its intrinsic disorder.

Materials and Methods

Molecular cloning, expression, and purification of Prosystemin

Prosystemin cDNA (GenBank: AAA34184.1) was PCR amplified and cloned in NcoI‐XhoI site of pETM11 (a kind gift from EMBL, Heidelberg) using site‐specific primers:

Forward:5′‐CGCGCGCCATGGGAACTCCTTC‐ATATGATATCA

Reverse:5′‐CGCGCGCTCGAGTTACTAGAGT‐TTATTATTGTCTGTTTGCATTTTGG‐3’

The generated plasmid was checked by sequencing and appropriate digestion with restriction enzymes. The expression of the recombinant construct was induced in E. coli BL21(DE3) cells by exposure to 2.0 mM IPTG (isopropyl‐β‐D‐1‐tiogalattopiranoside), for 16 h at 22°C. After centrifugation (20 min at 4°C at 6000g), the pellet was lysed in 20 mM Tris, 20 mM imidazole, 50 mM NaCl, 1 mM DTT pH 8.0, in presence of 0.1 mM phenylmethanesulfonyl fluoride, 5 mg/mL DNaseI, 0.1 mg/mL lysozyme and 1× protease inhibitors (Sigma‐Aldrich). Cells were disrupted by sonication and after centrifugation (30 min at 4°C at 30,000g) the soluble protein was purified by an ÄKTA FPLC, on a 1 mL HisTrap FF column (GE Healthcare), according to manufacturer's instruction (GE Healthcare). After elution, Prosys was dialyzed in 20 mM Tris, 50 mM NaCl, 100 µM PMSF,1 mM DTT, pH 8.0 and purified by means of ionic exchange chromatography on a 1 mL Mono Q HR 5/5 column and subsequently on a size exclusion chromatography (SEC) column. LC‐ESI‐MS analysis of the protein, performed as previously described,52 confirmed its identity. Biological assays were performed after extensive dialysis in PBS 1×.

Size exclusion chromatography

Size exclusion chromatography (SEC) was performed using a Superdex 75 10/300 GL column (GE Healthcare) in 20 mM Tris, 150 mM NaCl, 100 µM PMSF, 1 mM DTT buffer, pH 8.0. Calibration was carried out using the following standards (Sigma Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA): horse cytochrome c (12,400 Da), chicken ovalbumin (45,000 Da), bovine serum albumin (66,400 Da), carbonic anhydrase from bovine erythrocytes (29,000 Da) and recombinant carbonic anhydrase XIV (37,000 Da, homemade).

Circular dichroism

Circular dichroism (CD) spectra were recorded with a Jasco J‐715 spectropolarimeter equipped with a Peltier temperature control system (Model PTC‐423‐S) as described53, 54 using a 4 µM sample in 10 mM sodium phosphate buffer pH 7.4. The same parameters were applied to perform measurements in the temperature range of 10–80°C and titration with increasing concentrations of TFE (from 5% up to 30%). Data were analyzed using the DICHROWEB website. CDSSTR was used as a deconvolution method to evaluate the α‐helical content of the protein.

Light scattering

The oligomeric state of the protein was analyzed by size exclusion chromatography equipped with multiangle light scattering and quasi‐elastic light scattering detectors (SEC‐MALS‐QELS).55, 56 In particular, the experiment was set up by an ÄKTA FPLC, on a Superdex 75 10/300 GL (GE Healthcare) column linked to a multi angle detector (mini‐DAWN TREOS, Wyatt Technology) and a refraction index detector (Shodex RI 101). The data were analyzed with the program ASTRA 5.3.4.14 (Wyatt Technology). Dynamic light scattering (DLS) measurements were carried out using a Malvern nano zetasizer (Malvern, UK) as previously reported.57, 58 Briefly, the sample with a concentration of 0.4 mg/mL was placed in a disposable cuvette and held at 25°C during analysis. The same experiment was carried out in denaturing conditions, in presence of 7.4 M filtered urea (Sigma–Aldrich, Milan).

Tryptic protease sensitivity

TPCK treated trypsin (Sigma‐Aldrich, Milan) at an enzyme:substrate ratio of 1:100 and 1:200 (w:w) was added to an aliquot of Prosys (100 μg) in 50 mM Tris HCl buffer, pH 7.5. Proteolysis was monitored by SDS‐PAGE upon a digestion time of 30 min, 1 h, 2 h, 16 h at 26°C. Carbonic anhydrase II59 (homemade) was used as a control.

Nuclear magnetic resonance

Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) experiments were acquired at 298 K on a Varian Unity Inova 600 MHz spectrometer equipped with a cold probe. The NMR sample consisted of Prosys dissolved in a mixture PBS (phosphate buffer saline, 10 mM phosphates, 140 mM NaCl, 2.7 mM KCl, pH 7.4, Sigma‐Aldrich, Milan, Italy)/D2O (98% D, Armar Chemicals, Dottingen, Switzerland) 90/10 v/v with a total volume equal to 600 µL. Prosys sample (2 mg/mL) was analyzed through the 1D [1H] spectrum together with a set of 2D experiments: 2D [1H, 1H] TOCSY60 (70 ms mixing time), 2D [1H, 1H] NOESY61 (300 ms mixing time). 1D [1H] spectrum was acquired with a relaxation delay d1 of 1.5 s and 128 scans; 2D experiments were recorded with 32 scans, 128–256 FIDs in t1, 1024 or 2048 data points in t2. Water suppression was achieved by Excitation Sculpting.62 Chemical shifts were referenced to the water signal (4.75 ppm). Spectra were processed with VNMRJ (Varian by Agilent Technologies, Italy) and analyzed with NEASY63 comprised in the CARA software package (http://www.nmr.ch/).

Bioinformatics sequence analysis and ab initio modeling

Amino acid compositional analysis was performed by means of Composition Profiler tool (http://www.cprofiler.org), comparing the Prosys sequence with the reference value of the average amino acid frequencies of the Swiss‐Prot database (http://us.expasy.org.sprot).31 The Charge‐Hydrophobicity (CH) plot was generated as described by Uversky25 using data reported in literature (data partially taken from Ref. 32 for the intrinsically disordered protein, and randomly taken from PDB for natively folded proteins). In particular the mean net charge <R> and the mean hydrophobicity (H) were calculated using the program protParam at the EXPASY server (http://us.expasy.ch/tools).21 The CH border is described by the equation H=(R + 1.151)/2.785. The intrinsic disorder profile of Prosys was determined using two meta‐predictors PONDR‐FIT33 and DisMeta,34 which perform a combined consensus prediction from a broad range of different predictors. Secondary structure predictions were performed comparing the results of three different predictors: PSIPRED,35 SSpro,64 and QUARK.37, 65 Three‐dimensional structure of Prosys full‐length was predicted by QUARK ab initio server.37 QUARK program builds 3D structure models by replica‐exchange Monte Carlo simulation under the guide of an atomic‐level knowledge‐based force field.

Plant assays and gene expression analyses

Two set of leaves of 5 weeks‐old plants were cut with a sterile razor. The former was used to quantify Prosys expression 3, 6, and 24 h after wounding; the latter, 24 h after wounding, was treated with aliquots of 10 μL of 100 nM purified recombinant Prosys applied at the wound site. Expression of defense genes was monitored 6 and 24 h after Prosys application. Specific transcripts were quantified through qRT‐PCR using primers listed in Table S1 as previously described.66 Briefly, total RNA was obtained from leaves using a phenol/chloroform purification and a litium chloride precipitation based protocol. The synthesis of the first strand cDNA and qRT‐PCR were performed as already reported.66 Three plants and two technical replicates for each of them were used. The housekeeping gene EF‐1α was used as endogenous reference gene for the normalization of the expression levels of the target genes.66 Relative quantification of gene expression was carried out using the 2–ΔΔCt method.67

Insect bioassays

A feeding bioassay on S. littoralis larvae was carried out as previously described.9 Briefly, larvae were reared in an environmental chamber at 25 ± 2°C, 70 ± 5% RH and fed with an artificial diet composed by 41.4 g/L wheat germ, 59.2 g/L brewer's yeast and 165 g/L corn meal, supplemented with 5.9 g/L ascorbic acid, 1.8 g/L methyl 4‐hydroxybenzoate and 29.6 g/L agar. Newborn larvae were allowed to grow on this artificial diet until the second instar. Uniform second instar larvae were selected to form 4 groups of 15 individuals, and each group was used to evaluate larval weight and survival rate as affected by the following experimental treatments: wounded control spotted with PBS (WC PBS), unwounded leaf of the same plant, to assess any systemic effect (SC PBS), 100 pM Prosys spotted on a wound site (W Prosys), an unwounded leaf of the same treated‐plant (S Prosys). Experimental larvae were singly isolated in a tray well (Bio‐Ba‐8, Color‐Dec, Italy) covered by perforated plastic lids (Bio‐Cv‐1, Color‐Dec Italy), containing 2% agar (w/v) to create a moist environment required to keep turgid the tomato leaf disks, which were daily replaced, adjusting the size (initially of 2 cm2, later of 3, 4, and 5 cm2) in order to meet the food needs of growing larvae. Plastic trays were kept at 28°C 16:8 h light/dark photoperiod. Larval weight and mortality were recorded until pupation, which took place into plastic boxes containing vermiculite. Data were collected from two independent experimental replications. Differences in weight and survival rate were analyzed by One‐Way ANOVA.

Statistical analysis

Wounding experiment, relative to differences in Prosys transcript between wounded samples and unwounded control (three replicates for both of them) were analyzed by T‐test. Values of ΔCt for test and controls were compared using a two‐tailed T‐test. Similarly, differences in relative quantities of defense transcripts resulted upon Prosys application on the wound‐site have been analyzed by comparing ΔCt values for all replicates of controls and Prosys‐treated by a two‐tailed T‐test. Error bars referring to standard error have been displayed. For insect assay, larval weights were compared by One‐Way ANOVA followed by the Tukey–Kramer Honestly Significant Difference (HSD) multiple range test (P < 0.05). Survival curves of S. littoralis larvae, fed with test and control leaf disks, were compared by using Kaplan–Meier and log‐rank analysis.

Funding

This work was supported by the PON R&C 2007–2013 Grant financed by the Italian Ministry of University and Research (MIUR) in cooperation with the European Funds for the Regional Development (FESR), project GenopomPro and the Italian Cluster Agrifood “Safe&Smart.”

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest with the contents of this article.

Supporting information

Supplementary Table 1. Primers and their main features. Table lists primers used for qRT‐PCR including name, sequence, reference gene identifier, symbol and literature reference, amplicon size.

Figure S1. Tryptic protease sensitivity Comassie blue staining of SDS‐PAGE of Prosys digested with trypsin 1:200 at 26°C. The extent of digestion at different time intervals (0, 30 min, 1 hr, 2 hrs, 16 hrs) is indicated. M: mass molecular masses (kDa).

Figure S2: Ribbon representation of the ten 3D‐structure models predicted by QUARK ab initio server for Prosys. N‐terminal region (1‐70) is in blue; Central region (71‐140) is in green; C‐terminal region (140‐200) is in red.

Acknowledgments

We thank Marialetizia Carfora for her help during protein purification; we are grateful to Luca De Luca, Maurizio Amendola and Giosuè Sorrentino for their technical assistance.

Contributor Information

Emma Langella, Email: emma.langella@cnr.it.

Rosa Rao, Email: rao@unina.it.

Simona Maria Monti, Email: simonamaria.monti@cnr.it.

References

- 1. Schilmiller AL, Howe GA (2005) Systemic signaling in the wound response. Curr Opin Plant Biol 8:369–377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Green TR, Ryan CA (1972) Wound‐induced proteinase inhibitor in plant leaves: a possible defense mechanism against insects. Science 175:776–777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Ryan CA (1990) Protease inhibitors in plants: genes for improving defenses against insects and pathogens. Ann Rev Phytopathol 28:425–449. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Pearce G, Strydom D, Johnson S, Ryan CA (1991) A polypeptide from tomato leaves induces wound‐inducible proteinase inhibitor proteins. Science 253:895–897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Farmer EE, Ryan CA (1992) Octadecanoid precursors of jasmonic acid activate the synthesis of wound‐inducible proteinase inhibitors. Plant Cell 4:129–134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Ryan CA (2000) The systemin signaling pathway: differential activation of plant defensive genes. Biochim Biophys Acta 1477:112–121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Orozco‐Cárdenas ML, Narváez‐Vásquez J, Ryan CA (2001) Hydrogen peroxide acts as a second messenger for the induction of defense genes in tomato plants in response to wounding, systemin, and methyl jasmonate. Plant Cell 13:179–191. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Pearce G (2011) Systemin, hydroxyproline‐rich systemin and the induction of protease inhibitors. Curr Protein Pept Sci 12:399–408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Coppola M, Corrado G, Coppola V, Cascone P, Martinelli R, Digilio MC, Pennacchio F, Rao R (2015) Prosystemin overexpression in tomato enhances resistance to different biotic stresses by activating genes of multiple signaling pathways. Plant Mol Biol Rep 33:1270–1285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. McGurl B, Orozco‐Cardenas M, Pearce G, Ryan CA (1994) Overexpression of the Prosystemin gene in transgenic tomato plants generates a systemic signal that constitutively induces proteinase inhibitor synthesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 91:9799–9802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Dombrowski JE, Pearce G, Ryan CA (1999) Proteinase inhibitor‐inducing activity of the prohormone Prosystemin resides exclusively in the C‐terminal systemin domain. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 96:12947–12952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. McGurl B, Pearce G, Orozco‐Cardenas M, Ryan CA (1992) Structure, expression, and antisense inhibition of the systemin precursor gene. Science 255:1570–1573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Orozco‐Cardenas M, McGurl B, Ryan CA (1993) Expression of an antisense Prosystemin gene in tomato plants reduces resistance toward Manduca sexta larvae. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 90:8273–8276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Diaz J, ten Have A, van Kan JA (2002) The role of ethylene and wound signaling in resistance of tomato to Botrytis cinerea . Plant Physiol 129:1341–1351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. El Oirdi M, El Rahman TA, Rigano L, El Hadrami A, Rodriguez MC, Daayf F, Vojnov A, Bouarab K (2011) Botrytis cinerea manipulates the antagonistic effects between immune pathways to promote disease development in tomato. Plant Cell 23:2405–2421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Corrado G, Sasso R, Pasquariello M, Iodice L, Carretta A, Cascone P, Ariati L, Digilio MC, Guerrieri E, Rao R (2007) Systemin regulates both systemic and volatile signaling in tomato plants. J Chem Ecol 33:669–681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Degenhardt DC, Refi‐Hind S, Stratmann JW, Lincoln DE (2010) Systemin and jasmonic acid regulate constitutive and herbivore‐induced systemic volatile emissions in tomato, Solanum lycopersicum . Phytochemistry 71:2024–2037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Orsini F, Cascone P, De Pascale S, Barbieri G, Corrado G, Rao R, Maggio A (2010) Systemin‐dependent salinity tolerance in tomato: evidence of specific convergence of abiotic and biotic stress responses. Physiol Plant 138:10–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Corrado G, Arena S, Araujo‐Burgos T, Coppola M, Rocco M, Scaloni A, Rao R (2016) The expression of the tomato Prosystemin in tobacco induces alterations irrespective of its functional domain. Plant Cell Tiss Organ Cult 125:509–519. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Uversky VN (2013) Unusual biophysics of intrinsically disordered proteins. Biochim Biophys Acta 1834:932–951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Habchi J, Mamelli L, Darbon H, Longhi S (2010) Structural disorder within Henipavirus nucleoprotein and phosphoprotein: from predictions to experimental assessment. PloS One 5:e11684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Tornatore L, Marasco D, Dathan N, Vitale RM, Benedetti E, Papa S, Franzoso G, Ruvo M, Monti SM (2008) Gadd45 beta forms a homodimeric complex that binds tightly to MKK7. J Mol Biol 378:97–111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Sun X, Jones WT, Harvey D, Edwards PJB, Pascal SM, Kirk C, Considine T, Sheerin DJ, Rakonjac J, Oldfield CJ, Xue B, Dunker AK, Uversky VN, and others. (2010) N‐terminal domains of DELLA proteins are intrinsically unstructured in the absence of interaction with GID1/gibberellic acid receptors. J Biol Chem 285:11557–11571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Marin M, Thallmair V, Ott T (2012) The intrinsically disordered N‐terminal region of AtREM1.3 remorin protein mediates protein‐protein interactions. J Biol Chem 287:39982–39991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Uversky VN (2002) Natively unfolded proteins: a point where biology waits for physics. Protein Sci 11:739–756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Uversky VN (2002) What does it mean to be natively unfolded?. Eur J Biochem 269:2–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Buck M (1998) Trifluoroethanol and colleagues: cosolvents come of age. Recent studies with peptides and proteins. Q Rev Biophys 31:297–355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Tantos A, Szrnka K, Szabo B, Bokor M, Kamasa P, Matus P, Bekesi A, Tompa K, Han KH, Tompa P (2013) Structural disorder and local order of hNopp140. Biochim Biophys Acta 1834:342–350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Johansson J, Gudmundsson GH, Rottenberg ME, Berndt KD, Agerberth B (1998) Conformation‐dependent antibacterial activity of the naturally occurring human peptide LL‐37. J Biol Chem 273:3718–3724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. McGurl B, Ryan CA (1992) The organization of the Prosystemin gene. Plant Mol Biol 20:405–409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Vacic V, Uversky VN, Dunker AK, Lonardi S (2007) Composition Profiler: a tool for discovery and visualization of amino acid composition differences. BMC Bioinform 8:211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Uversky VN, Gillespie JR, Fink AL (2000) Why are “natively unfolded” proteins unstructured under physiologic conditions?. Proteins 41:415–427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Xue B, Dunbrack RL, Williams RW, Dunker AK, Uversky VN (2010) PONDR‐FIT: a meta‐predictor of intrinsically disordered amino acids. Biochim Biophys Acta 1804:996–1010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Huang YJ, Acton TB, Montelione GT (2014) DisMeta: a meta server for construct design and optimization. Methods Mol Biol 1091:3–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Buchan DW, Minneci F, Nugent TC, Bryson K, Jones DT (2013) Scalable web services for the PSIPRED Protein Analysis Workbench. Nucleic Acids Res 41:W349–W357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Pollastri G, Przybylski D, Rost B, Baldi P (2002) Improving the prediction of protein secondary structure in three and eight classes using recurrent neural networks and profiles. Proteins 47:228–235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Xu D, Zhang Y (2012) Ab initio protein structure assembly using continuous structure fragments and optimized knowledge‐based force field. Proteins 80:1715–1735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Delano JP, Dombrowski JE, Ryan CA (1999) The expression of tomato Prosystemin in Escherichia coli: a structural challenge. Protein Expr Purif 17:74–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Tompa P (2002) Intrinsically unstructured proteins. Trends Biochem Sci 27:527–533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Oldfield CJ, Meng J, Yang JY, Yang MQ, Uversky VN, Dunker AK (2008) Flexible nets: disorder and induced fit in the associations of p53 and 14‐3‐3 with their partners. BMC Genom 9:S1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Dyson HJ, Wright PE (2002) Coupling of folding and binding for unstructured proteins. Curr Opin Struct Biol 12:54–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Beloshistov RE, Dreizler K, Galiullina RA, Tuzhikov AI, Serebryakova MV, Reichardt S, Shaw J, Taliansky ME, Pfannstiel J, Chichkova NV, Stintzi A, Schaller A, Vartapetian AB. (2017) Phytaspase‐mediated precursor processing and maturation of the wound hormone systemin. New Phytolog. doi: 10.1111/nph.14568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Wright PE, Dyson HJ (1999) Intrinsically unstructured proteins: re‐assessing the protein structure‐function paradigm. J Mol Biol 293:321–331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Uversky VN (2010) The mysterious unfoldome: structureless, underappreciated, yet vital part of any given proteome. J Biomed Biotechnol 2010:568068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Uversky VN, Oldfield CJ, Midic U, Xie H, Xue B, Vucetic S, Iakoucheva LM, Obradovic Z, Dunker AK (2009) Unfoldomics of human diseases: linking protein intrinsic disorder with diseases. BMC Genom 10:S7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Dunker AK, Oldfield CJ, Meng J, Romero P, Yang JY, Chen JW, Vacic V, Obradovic Z, Uversky VN (2008) The unfoldomics decade: an update on intrinsically disordered proteins. BMC Genom 9:S1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Sun X, Jones WT, Rikkerink EH (2012) GRAS proteins: the versatile roles of intrinsically disordered proteins in plant signalling. Biochem J 442:1–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Sun X, Rikkerink EH, Jones WT, Uversky VN (2013) Multifarious roles of intrinsic disorder in proteins illustrate its broad impact on plant biology. Plant Cell 25:38–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Marin M, Ott T (2014) Intrinsic disorder in plant proteins and phytopathogenic bacterial effectors. Chem Rev 114:6912–6932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Hundertmark M, Hincha DK (2008) LEA (late embryogenesis abundant) proteins and their encoding genes in Arabidopsis thaliana . BMC Genom 9:118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Habchi J, Tompa P, Longhi S, Uversky VN (2014) Introducing protein intrinsic disorder. Chem Rev 114:6561–6588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Truppo E, Supuran CT, Sandomenico A, Vullo D, Innocenti A, Di Fiore A, Alterio V, De Simone G, Monti SM (2012) Carbonic anhydrase VII is S‐glutathionylated without loss of catalytic activity and affinity for sulfonamide inhibitors. Bioorg Med Chem Lett 22:1560–1564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Troise AD, Dathan NA, Fiore A, Roviello G, Di Fiore A, Caira S, Cuollo M, De Simone G, Fogliano V, Monti SM (2014) Faox enzymes inhibited Maillard reaction development during storage both in protein glucose model system and low lactose UHT milk. Amino Acids 46:279–288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Dathan NA, Alterio V, Troiano E, Vullo D, Ludwig M, De Simone G, Supuran CT, Monti SM (2014) Biochemical characterization of the chloroplastic beta‐carbonic anhydrase from Flaveria bidentis (L.) “Kuntze”. J Enzyme Inhib Med Chem 29:500–504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Ascione G, de Pascale D, De Santi C, Pedone C, Dathan NA, Monti SM (2012) Native expression and purification of hormone‐sensitive lipase from Psychrobacter sp. TA144 enhances protein stability and activity. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 420:542–546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. D'Ambrosio K, Lopez M, Dathan NA, Ouahrani‐Bettache S, Kohler S, Ascione G, Monti SM, Winum JY, De Simone G (2014) Structural basis for the rational design of new anti‐Brucella agents: the crystal structure of the C366S mutant of L‐histidinol dehydrogenase from Brucella suis . Biochimie 97:114–120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Del Giudice R, Arciello A, Itri F, Merlino A, Monti M, Buonanno M, Penco A, Canetti D, Petruk G, Monti SM, Relini A, Pucci P, Piccoli R, Monti DM, and others. (2016) Protein conformational perturbations in hereditary amyloidosis: differential impact of single point mutations in ApoAI amyloidogenic variants. Biochim Biophys Acta 1860:434–444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Di Lelio I, Caccia S, Coppola M, Buonanno M, Di Prisco G, Varricchio P, Franzetti E, Corrado G, Monti SM, Rao R, Casartelli M, Pennacchio F (2014) A virulence factor encoded by a polydnavirus confers tolerance to transgenic tobacco plants against lepidopteran larvae, by impairing nutrient absorption. PloS One 9:e113988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. D'Ambrosio K, Carradori S, Monti SM, Buonanno M, Secci D, Vullo D, Supuran CT, De Simone G (2015) Out of the active site binding pocket for carbonic anhydrase inhibitors. Chem Commun 51:302–305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Griesinger C, Otting G, Wuethrich K, Ernst RR (1988) Clean TOCSY for proton spin system identification in macromolecules. J Am Chem Soc 110:7870–7872. [Google Scholar]

- 61. Kumar A, Ernst RR, Wuthrich K (1980) A two‐dimensional nuclear Overhauser enhancement (2D NOE) experiment for the elucidation of complete proton‐proton cross‐relaxation networks in biological macromolecules. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 95:1–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Hwang TL, Shaka AJ (1995) Water suppression that works. Excitation sculpting using arbitrary waveforms and pulsed field gradients. J Magn Reson 112:275–279. [Google Scholar]

- 63. Bartels C, Xia TH, Billeter M, Guntert P, Wuthrich K (1995) The program XEASY for computer‐supported NMR spectral analysis of biological macromolecules. J Biomol NMR 6:1–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Cheng J, Randall AZ, Sweredoski MJ, Baldi P (2005) SCRATCH: a protein structure and structural feature prediction server. Nucleic Acids Res 33:W72–W76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Buonanno M, Langella E, Zambrano N, Succoio M, Sasso E, Alterio V, Di Fiore A, Sandomenico A, Supuran CT, Scaloni A, Monti SM, De Simone G (2017) Disclosing the interaction of carbonic anhydrase IX with cullin‐associated NEDD8‐dissociated protein 1 by molecular modeling and integrated binding measurements. ACS Chem Biol 12:1460–1465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Corrado G, Alagna F, Rocco M, Renzone G, Varricchio P, Coppola V, Coppola M, Garonna A, Baldoni L, Scaloni A, Rao R (2012) Molecular interactions between the olive and the fruit fly Bactrocera oleae. BMC Plant Biol 12:86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD (2001) Analysis of relative gene expression data using real‐time quantitative PCR and the 2(‐Delta Delta C(T)) method. Methods 25:402–408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Table 1. Primers and their main features. Table lists primers used for qRT‐PCR including name, sequence, reference gene identifier, symbol and literature reference, amplicon size.

Figure S1. Tryptic protease sensitivity Comassie blue staining of SDS‐PAGE of Prosys digested with trypsin 1:200 at 26°C. The extent of digestion at different time intervals (0, 30 min, 1 hr, 2 hrs, 16 hrs) is indicated. M: mass molecular masses (kDa).

Figure S2: Ribbon representation of the ten 3D‐structure models predicted by QUARK ab initio server for Prosys. N‐terminal region (1‐70) is in blue; Central region (71‐140) is in green; C‐terminal region (140‐200) is in red.