Abstract

This study analyzes inpatient progress notes to determine the documentation practices of medical students, residents, and hospitalists.

The traditional goal of progress notes is to provide a concise, up-to-date reflection of the patient’s condition and the clinician’s thought process. Electronic health records (EHRs) allow physicians writing these notes to supplement traditional manual data entry with copied or imported text. However, copying or importing text increases the risk of including outdated, inaccurate, or unnecessary information, which can undermine the utility of notes and lead to a clinical error. Previous studies quantifying copied text were limited by available tools, which could not distinguish manually modified text from automatically updated imported values in electronic note templates. We used a new EHR tool that distinguishes manual, imported, and copied text in hospital progress notes with character-by-character granularity to describe documentation practices by medical students, residents, and direct care hospitalists.

Methods

This study took place at the University of California San Francisco Medical Center using an inpatient EHR (Epic; Epic Systems Corporation). We analyzed inpatient progress notes written by direct care hospitalists, residents, and medical students on a general medicine service over an 8-month period, from January 10, 2016, to August 31, 2016. Only note text written by primary authors was included in the analysis; addenda and attestations to resident and medical student notes were excluded. This study was reviewed and approved by the institutional review board of the University of California, San Francisco, who also waived patient informed consent because the large number of records required made contacting all potential subjects impractical and because all research materials were previously collected for nonresearch purposes.

After a recent software update, the EHR now identifies the provenance of every character that is present in a signed note—that is, whether that character was typed fresh (“manually entered”), pulled in from another source such as a medication list (“imported”), or pasted from a previous note or elsewhere (“copied”). Clinicians can opt to see this information, which is hidden by default but is logged in the EHR for every note written since the upgrade. We examined each note for the number and percentage of manually entered, imported, and copied characters. We used the nonparametric, 1-way Kruskal-Wallis test to examine differences between provider types. We performed data manipulations using the open source tool DB Browser for SQLite version 3.9.1, and we conducted the analysis using the free software R version 3.3.3 (R).

Results

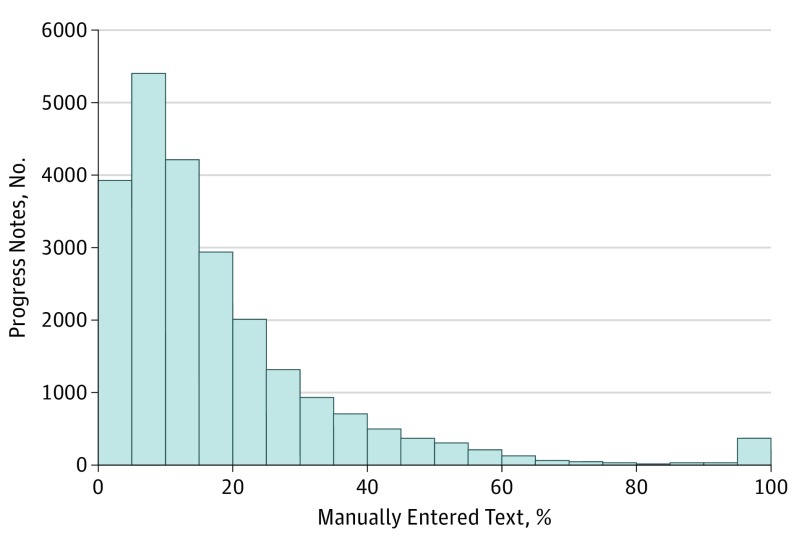

We analyzed 23 630 notes written by 460 clinicians. In a typical note, 18% of the text was manually entered; 46%, copied; and 36%, imported (Figure). Residents manually entered less (11.8% of the text) and copied more (51.4%) than did medical students (16.2% of the text manually entered and 49.0% copied) or direct care hospitalists (14.1% of the text manually entered and 47.9% copied) (for differences in manual entry proportion, P = 2.2 × 10−16; for copy proportion, P = 2.16 × 10−12). Direct care hospitalists wrote the shortest notes (5006 total characters) compared with medical students (7053) and residents (6720).

Figure. Number of Progress Notes With a Given Percentage of Manually Entered Text.

Distribution of progress notes for all clinician types with a given percentage of manually entered text.

Discussion

This study analyzed the provenance of progress note text with character-level granularity. Less than one-fifth of note content was manually entered, a finding that was difficult to obtain with previous methods. Although we conducted a single-center, single-service analysis, we observed patterns that were consistent with what has been measured in previous studies and what clinicians have observed anecdotally. Furthermore, we were able to access only the aggregated provenance counts of whole notes and could not yet examine section-specific provenance data (eg, physical examination).

Future analysis will examine how copied and imported text is used to fulfill the various functions of a note, such as billing or clinical history recall. This finding could spur EHR design that makes copied and imported information readily visible to clinicians as they are writing a note but, ultimately, does not store that information in the note. For example, copied text used as a hospital course record to facilitate the creation of a discharge summary may represent an opportunity for the EHR to provide an alternative space for discharge information. Alternately, copied text that represents a belief that more text leads to higher billing suggests an opportunity for educating clinicians in how notes are coded.

As mentioned, this study’s limitations included its single-center, single-service focus and inability to access section-specific provenance data.

Clinicians spend time every day writing progress notes. Understanding their practice and the needs of their audience could spur improvements that restore the utility of this documentation.

References

- 1.Stewart E, Kahn D, Lee E, et al. . Internal medicine progress note writing attitudes and practices in an electronic health record. J Hosp Med. 2015;10(8):525-529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Singh H, Giardina TD, Meyer AN, Forjuoh SN, Reis MD, Thomas EJ. Types and origins of diagnostic errors in primary care settings. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173(6):418-425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tsou AY, Lehmann CU, Michel J, Solomon R, Possanza L, Gandhi T. Safe practices for copy and paste in the HER: systematic review, recommendations, and novel model for health IT collaboration. Appl Clin Inform. 2017;8(1):12-34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hirschtick RE. A piece of my mind: copy-and-paste. JAMA. 2006;295(20):2335-2336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Thornton JD, Schold JD, Venkateshaiah L, Lander B. Prevalence of copied information by attendings and residents in critical care progress notes. Crit Care Med. 2013;41(2):382-388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ibach B, Stewart D, Chang R, Laing T Epidemiology of copy and pasting in the medical record at a tertiary care academic medical center [abstract]. J Hosp Med http://www.shmabstracts.com/abstract/epidemiology-of-copy-and-pasting-in-the-medical-record-at-a-tertiarycare-academic-medical-center/. Published 2012. Accessed January 23, 2017.