Abstract

This observational study examines the association of labeling vegetables with indulgent descriptions and overall vegetable consumption compared with labeling vegetables with basic or health-focused labels.

In response to increasing rates of obesity, many dining establishments have focused on promoting the health properties and benefits of nutritious foods to encourage people to choose healthier options. Ironically however, health-focused labeling of food may be counter-effective, as people rate foods that they perceive to be healthier as less tasty. Healthy labeling is even associated with higher hunger hormone levels after consuming a meal compared with when the same meal is labeled indulgently. How can we make healthy foods just as appealing as more classically indulgent and unhealthy foods? Because healthy foods are routinely labeled with fewer appealing descriptors than standard foods, this study tested whether labeling vegetables with the flavorful, exciting, and indulgent descriptors typically reserved for less healthy foods could increase vegetable consumption.

Methods

The study was conducted in a large university cafeteria serving a mean (SD) 607 (52) diners per weekday lunch (52.5% undergraduate students, 32.5% graduate students, 15.1% staff/other). The Stanford University institutional review board approved this study and waived informed consent. Data were collected each weekday for the 2016 autumn academic quarter (n = 46 days). Each day, one featured vegetable was randomly labeled in 1 of 4 ways: basic, healthy restrictive, healthy positive, or indulgent (Table). No changes were made to how the vegetables were prepared or served. Each day research assistants discretely recorded the number of diners selecting the vegetable and weighed the mass of vegetables taken from the serving bowl. We predicted that vegetables labeled with indulgent descriptors would be chosen more than the same vegetables labeled with basic or healthy descriptors. Means were compared using analysis of variance.

Table. Example Vegetable Descriptions by Condition.

| Indulgent | Basic | Healthy Restrictive | Healthy Positive |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dynamite chili and tangy lime-seasoned beets | Beets | Lighter-choice beets with no added sugar | High-antioxidant beets |

| Rich buttery roasted sweet corn | Corn | Reduced-sodium corn | Vitamin-rich corn |

| Sweet sizzlin' green beans and crispy shallots | Green beans | Light ‘n’ low-carb green beans and shallots | Healthy energy-boosting green beans and shallots |

| Zesty ginger-turmeric sweet potatoes | Sweet potatoes | Cholesterol-free sweet potatoes | Wholesome sweet potato superfood |

| Twisted garlic-ginger butternut squash wedges | Butternut squash | Butternut squash with no added sugar | Antioxidant-rich butternut squash |

| Slow-roasted caramelized zucchini bites | Zucchini | Lighter-choice zucchini | Nutritious green zucchini |

| Tangy ginger bok choy and banzai shiitake mushrooms | Bok choy and mushrooms | Low-sodium bok choy and mushrooms | Wholesome bok choy and mushrooms |

| Twisted citrus-glazed carrots | Carrots | Carrots with sugar-free citrus dressing | Smart-choice vitamin C citrus carrots |

Results

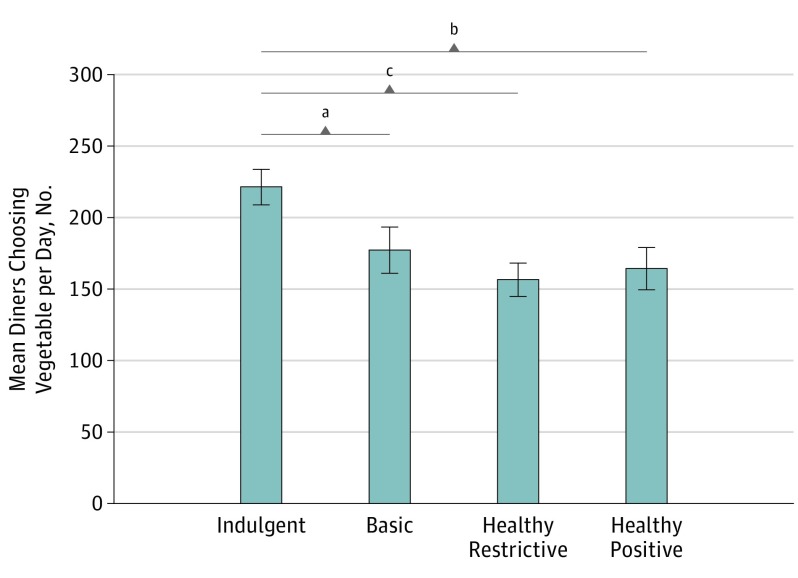

During the study period, 8279 of 27 933 total diners selected the vegetable (29.6%). Labeling had a significant effect on both the number of diners selecting the vegetable (F3,42 = 2.83; P = .05) and the mass of vegetables consumed (F3,42 = 4.29; P = .01). Pairwise comparisons (Figure) revealed that labeling vegetables indulgently resulted in 25% more people selecting the vegetable than in the basic condition (95% CI, 1%-49%; P = .04), 41% more people than in the healthy restrictive condition (95% CI, 18%-64%; P = .001), and 35% more people than in the healthy positive condition (95% CI, 10%-60%; P = .01). Similarly, labeling vegetables indulgently resulted in a 23% increase in mass of vegetables consumed compared with the basic condition (95% CI, 3%-43%; P = .03) and a 33% increase in mass of vegetables consumed compared with the healthy restrictive condition (95% CI, 11%-53%; P = .004), but a nonsignificant 16% increase in mass consumed compared with the healthy positive condition (95% CI, −5% to 36%; P = .14). There were no significant differences among the basic, healthy restrictive, and healthy positive conditions for either outcome (P > .25 for all).

Figure. Diners per Day Choosing Vegetables by Condition.

Bars represent mean number of diners choosing the vegetable per day by condition; error bars represent standard error. Two-tailed t tests were used for pairwise comparisons, and P ≤ .05 were considered statistically significant. aP < .05; bP < .01; cP < .001.

Discussion

Labeling vegetables with indulgent descriptors significantly increased the number of people choosing vegetables and the total mass of vegetables consumed compared with basic or healthy descriptions, despite no changes in vegetable preparation. These results challenge existing solutions that aim to promote healthy eating by highlighting health properties or benefits and extend previous research that used other creative labeling strategies, such as using superhero characters, to promote vegetable consumption in children. Our results represent a robust, applicable strategy for increasing vegetable consumption in adults: using the same indulgent, exciting, and delicious descriptors as more popular, albeit less healthy, foods. This novel, low-cost intervention could easily be implemented in cafeterias, restaurants, and consumer products to increase selection of healthier options. Though we were unable to measure how much food was eaten by patrons individually, people generally eat 92% of self-served food, regardless of portion size and food type. Further research should assess how well the effects generalize to other settings and explore the potential of indulgent labeling to help alleviate the pervasive cultural mindset that healthy foods are not tasty.

References

- 1.Turnwald BP, Jurafsky D, Conner A, Crum AJ. Reading between the menu lines: are restaurants’ descriptions of “healthy” foods unappealing? Health Psychol. 2017. In press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Raghunathan R, Naylor RW, Hoyer WD. The unhealthy=tasty intuition and its effects on taste inferences, enjoyment, and choice of food products. J Mark. 2006;70(4):170-184. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Crum AJ, Corbin WR, Brownell KD, Salovey P. Mind over milkshakes: mindsets, not just nutrients, determine ghrelin response. Health Psychol. 2011;30(4):424-429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hanks AS, Just DR, Brumberg A. Marketing vegetables in elementary school cafeterias to increase uptake. Pediatrics. 2016;138(2):e20151720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wansink B, Just DR, Payne CR, Klinger MZ. Attractive names sustain increased vegetable intake in schools. Prev Med. 2012;55(4):330-332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wansink B, Johnson KA. The clean plate club: about 92% of self-served food is eaten. Int J Obes (Lond). 2015;39(2):371-374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]